It was a dark and stormy night…No, no, no. A gibbous moon hung…No, it didn’t. Lightning shattered the evening sky…Nope. No, no, no. No, it didn’t. Okay. It was an average, normal day in 1950’s London when Boris Karloff went on a ghost hunt. Yes, that’s it….Well…carry on…

It was an average, normal day in 1950’s London when Boris Karloff went on a ghost hunt.

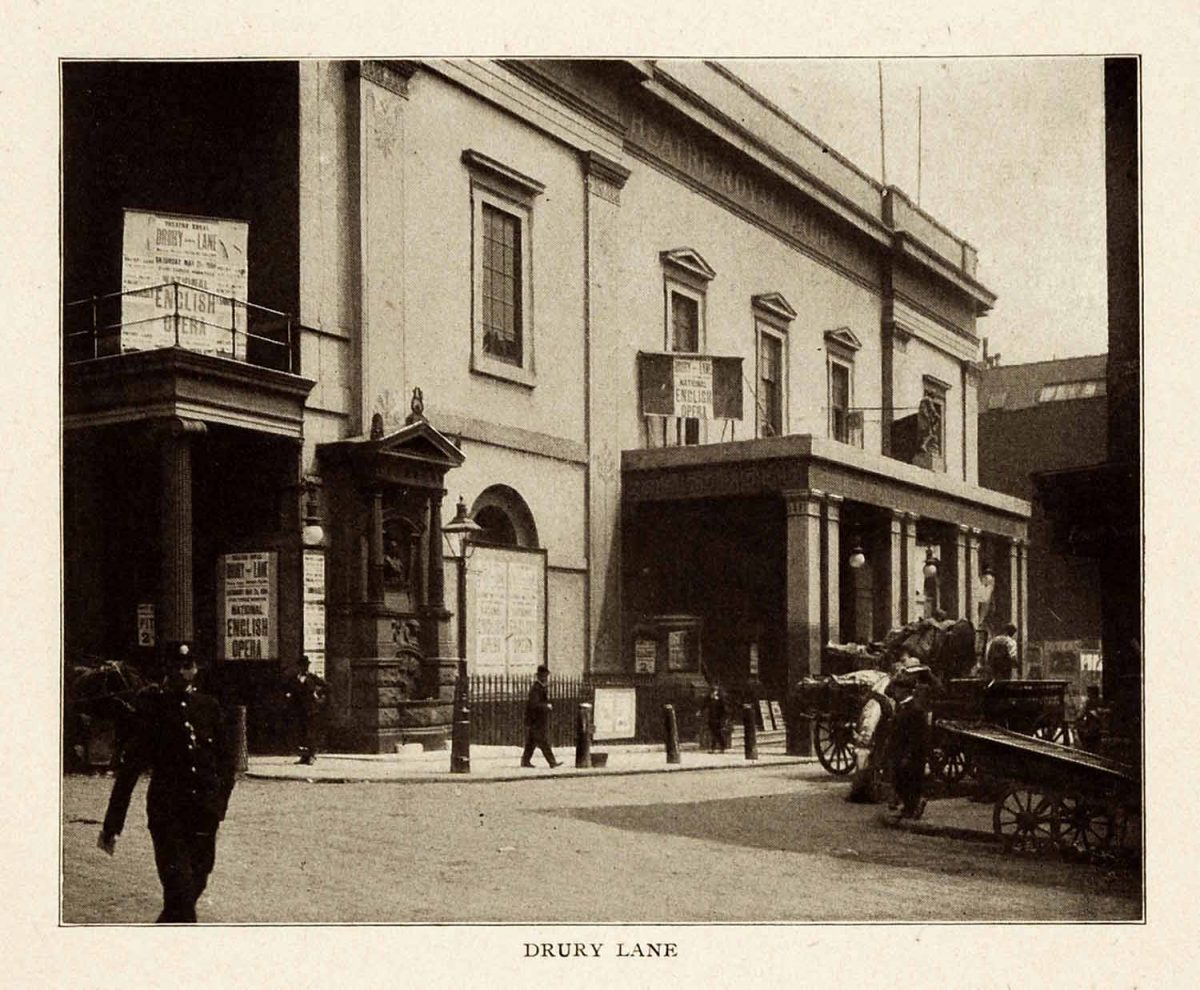

Karloff had been invited to visit the Theatre Royal Drury Lane by theatre historian W. Macqueen Pope to (hopefully) witness its most famous ghost the Man in Grey. (Cue Scooby and Shaggy saying “Zoinks!”) The Gentleman of Horror was delighted to take part. He had not long returned to England having spent the past forty-plus years living and working in America.

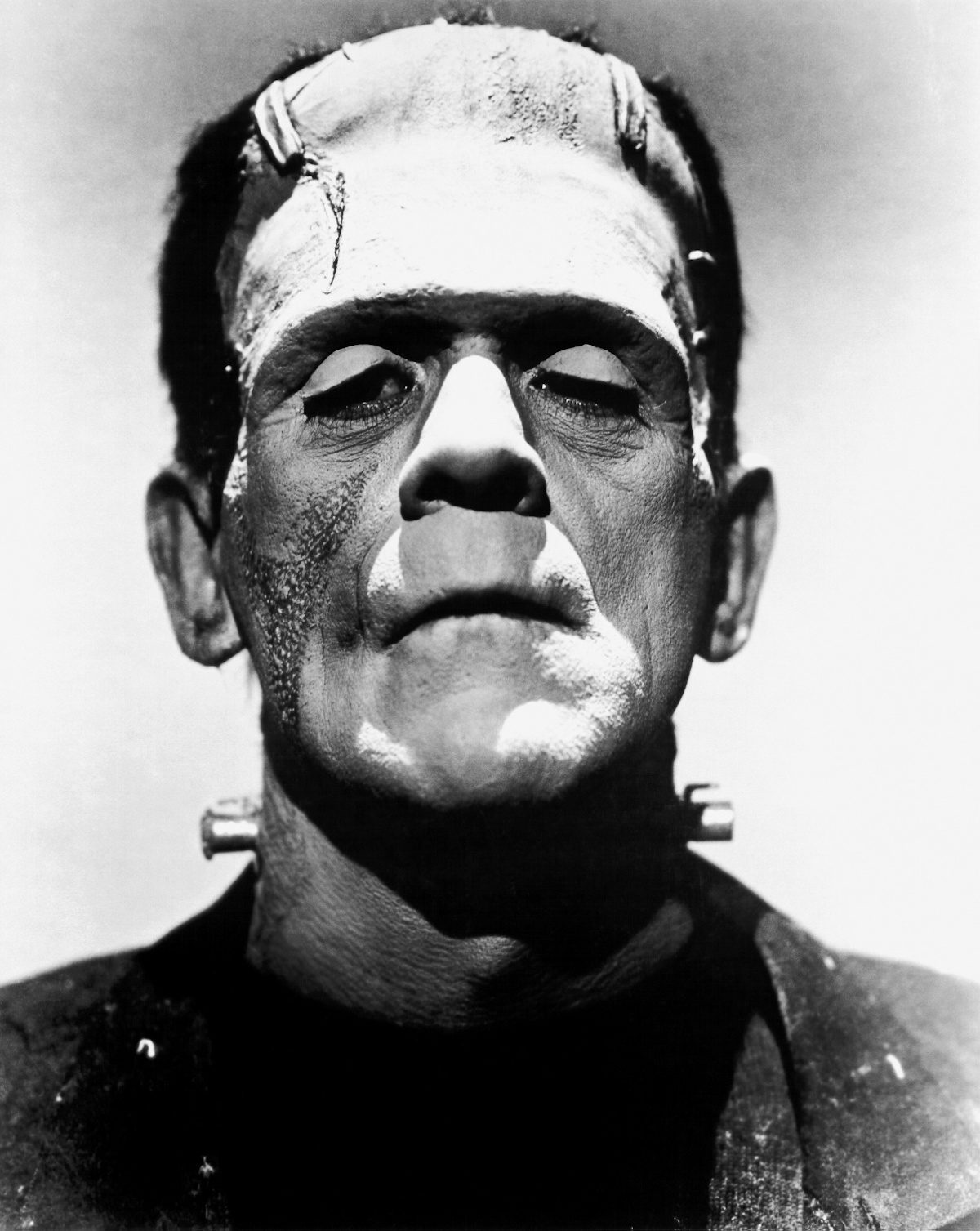

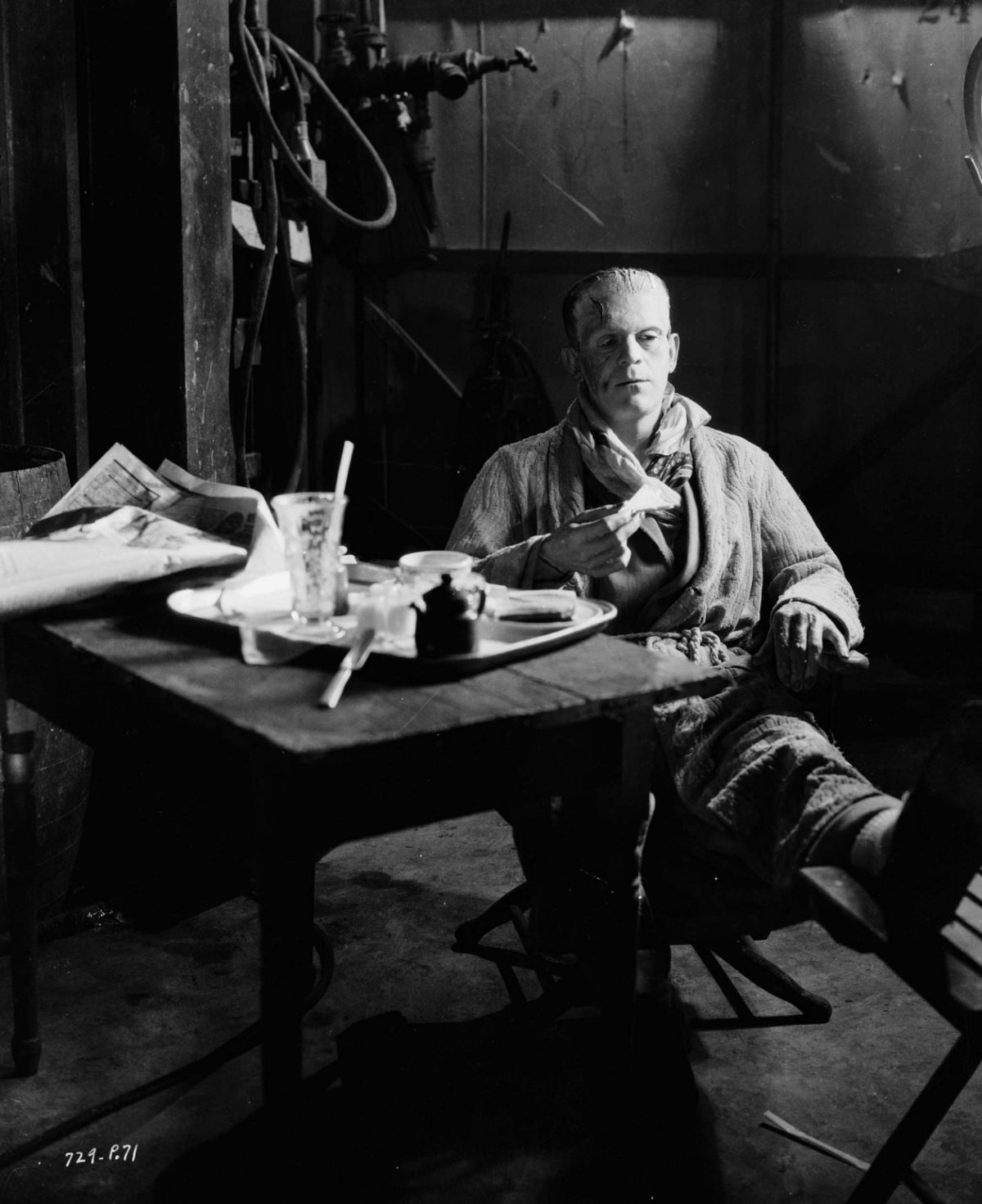

Who was Karloff? Why the biggest Horror movie star on the planet, whose name on a title could always guarantee production money if not always a profit at the box office. Karloff had made his name as the Creature in James Whale’s Frankenstein in 1931. He had established his reputation as the “King of Horror” by starring in some of the greatest horror movies ever made like The Mummy, The Bride of Frankenstein, The Ghoul, The Black Cat, Isle of the Dead, The Body Snatcher, and many, many more (Look him up, if yah dunno..). I’m talking real horror movies, crafted by character, story, acting and direction, not chainsaw splatter or pig-fucking monkeys from Hell. Karloff was back in England where he’d starred in the hit TV series Colonel March of Scotland Yard and more recently had just finished The Haunted Strangler and Corridors of Blood.

Though in the twilight of his career, Karloff had recently gained a new generation of fans after television screened his old horror movies. Surprisingly, these old flicks still had the power to shock, particularly with a tiny but vocal minority of moral arbiters who considered “horror movies” to be a malign influence on young, innocent minds. These deluded individuals demanded horror movies ought to be censored according to their rules. (Cue Scooby and Shaggy saying, “Fuck off.”) Karloff was horrified at the thought of this:

‘Censorship of any sort is a fearful thing.’ [Karloff] told Herbert Kretzmer of the Daily Sketch in 1958, ‘and the word DON’T is the most terrifying in the language.’

‘I am opposed to censorship in any form,’ he said in his 1957 article in Films and Filming.

‘Censorship always seems to me to be a mistrust of people’s intelligence. I believe that good taste takes care of licence. It is also worth remembering that one does not have to go and see a film. Naturally, good taste plays a very, important part in the telling of a horror story on film. Some have taste, others regrettably have not. As there are no rules laid down to give an indication of good taste it is up to the film’s makers. You are walking a very narrow tightrope when you make such a film. It is building the illusion of the impossible and giving it the semblance of reality that is of prime importance. The moment the film becomes stupid the audience will laugh and the illusion is lost. . . never to be regained. The story must be intelligent and coherent as well as being unusual and bizarre . . . in fact just like a fairy tale or a good folk story.’

Outside the theatre, Karloff was joined by fellow thesps Tod Slaughter and Valentine Dyall, alongside editor of Psychic News Fred Archer and a former Scotland Yard detective Robert Fabian. Macqueen Pope introduced himself and merrily led his guests inside the theatre.

The Theatre Royal is reputed to be the most haunted theatre in the world. It has a cast list of ghosts which have long been witnessed by actors, audience members, and recorded in books and tales of theatrical folklore. These ghosts include legendary performers like Joseph Grimaldi, Dan Leno, and the “notorious actor Charles Maklin, who once killed a man in an argument over a wig.”

Of course, its most famous ghost is the mysterious Man in Grey, whose identity has never been fully established. However, Fred Archer in his book Ghost Writer recounted his visit to the theatre with Karloff and co. and suggestsed a possible cause of the haunting:

About one hundred years ago…the wall of the theatre adjoining Russell Street had to be repaired. The workmen found that a part of the wall gave a hollow ring, and they broke through. It was a secret room that they had discovered–inhabited by a skeleton with a dagger stuck between its ribs. On the other side of the wall of that apartment is the spot where the ghost is most often seen to manifest.

This ghost was “always attired in a long grey cloak.”

Below the cloak protrudes the end of a sword, and his legs are encased in a pair of riding boots.

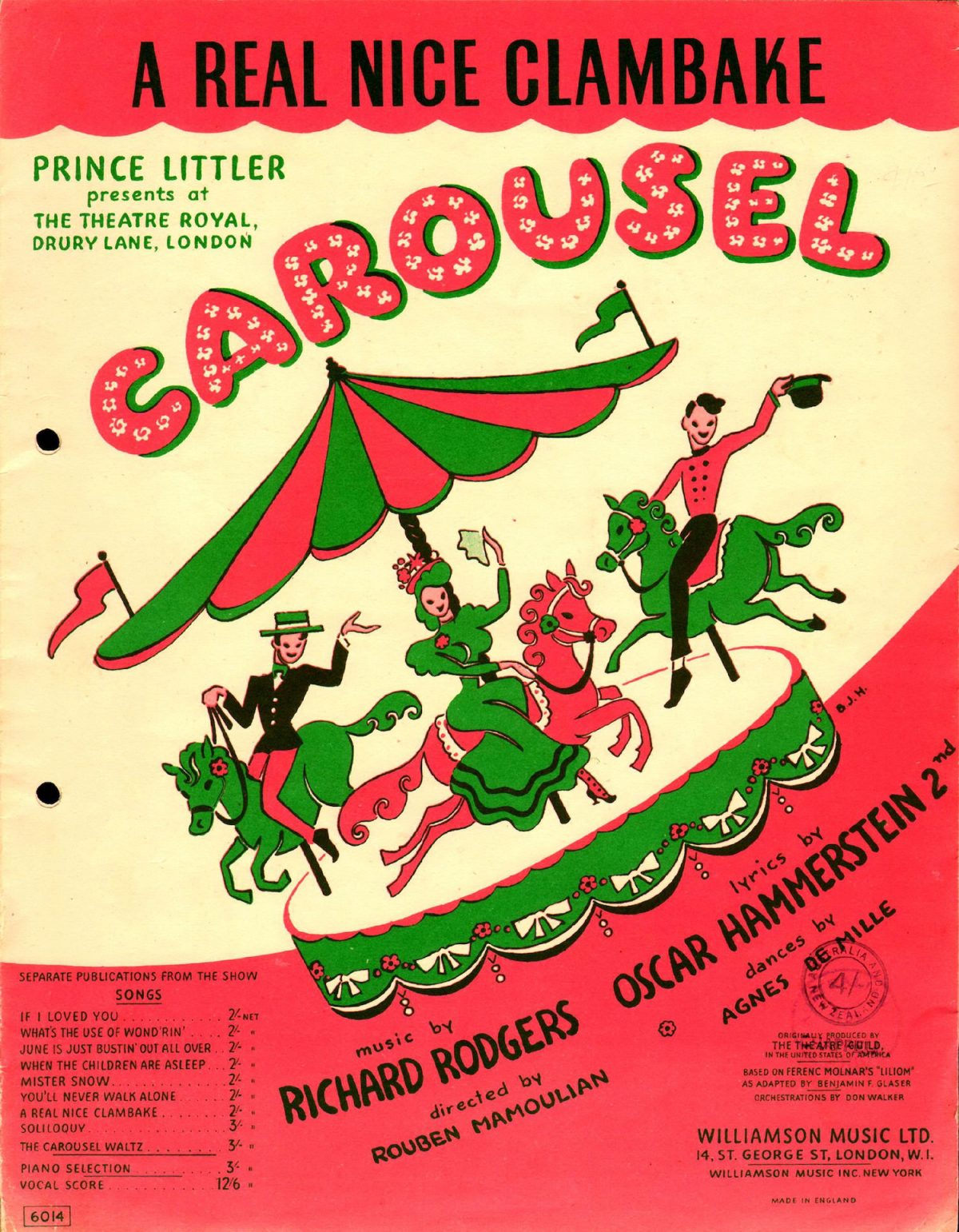

To see the Man in Grey is considered a good omen, and he said to only appear when a show is going to be a success. The Theatre Royal has hosted a long succession of stage hits–Oklahoma, Carousel, The King and I, and My Fair Lady. Archer recounts one actor’s experience of the ghost:

Morgan Davies, a leading player in Carousel, one of Drury Lane’s biggest hits, told me soon after the run began how he had seen the ghost.

It was a Saturday matinee and, as usual, the house was full–except for a solitary box which attracted Davies’ attention for that reason. Then, while on the stage, Davies looked again, and registered the fact the box was now occupied. The figure he saw wore a long grey cloak, open at the front revealing sleeves adorned with ruffles. Davies realised with a shock that the occupant in the box was standing–and was transparent. Davies could see straight through him to the door of the box which was illumined by a glow of light. During that scene Davies was on stage for twenty-five minutes. For at least ten minutes of that time, he told me emphatically, the ghost stood there, motionless save for a slight swaying movement and a gesture he made with his arms. Then he disappeared.

The famous five and their merry guide wandered through the theatre. Lights were dim and there was a sense of something just about to happen. If not the ghost of the Man in Grey, then perhaps one of the other spectres or at least the curtain up on some glorious production. They talked quietly, almost reverentially, together, while the enthusiastic Macqueen Pope led them closer to the stage. It was a visit that deserved a camera crew to film proceedings and capture the high expectations and the inevitable disappointment that was to follow. As Archer recalled:

I have never seen the “Man in Grey” myself. Perhaps I went to meet him with the wrong company. For with me were Boris Karloff, the Frankenstein monster, Tod Slaughter, who gained his reputation in such horrors as The Murder in the Red Barn and Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber, Valentine Dyall, the doom=portending voice of the “Man in Black” series of broadcast terror plays, and a famous real-life detective, ex-Superintendant Robert Fabian of Scotland Yard.

Our guide was W. Macqueen Pope, historian of Drury Lane, who has seen the “Man un Grey” more times than anyone. Often he tried to talk to the ghost, he told me, but it always vanished before he could get very near. Whether he was scared away by the reputations of Karloff, Slaughter and Valentine Dyall–three of the nicest “ghouls” I have ever met–or was frightened that Fabian might arrest him for loitering, I cannot say. But the ghost did not appear on that occasion. Not even Macqueen Pope caught a glimpse of him.

Perhaps if this whole adventure had commenced on some dark and stormy night as banshees shrieked and werewolves howled…then things may have been different?

It is left unrecorded whether Karloff and his fellow ghost hunters were disappointed by a lack of paranormal activity. One would surmise a refreshing gin and tonic in the green room would have remedied any ill feeling. It is often suggested that actors are more susceptible to seeing ghosts and things beyond our ken, in part because they are more open to suggestion. Surprisingly, Karloff was at times very superstitious, in particular when preparing for a role when he repeated actions which he had first performed while filming Frankenstein. For example, putting on a costume or leaving a dressing room in certain manner. He also believed in luck. Before his success, he never doubted his luck, even if he was down to his last five cents, Karloff said he always believed he would make it no matter how long it took.

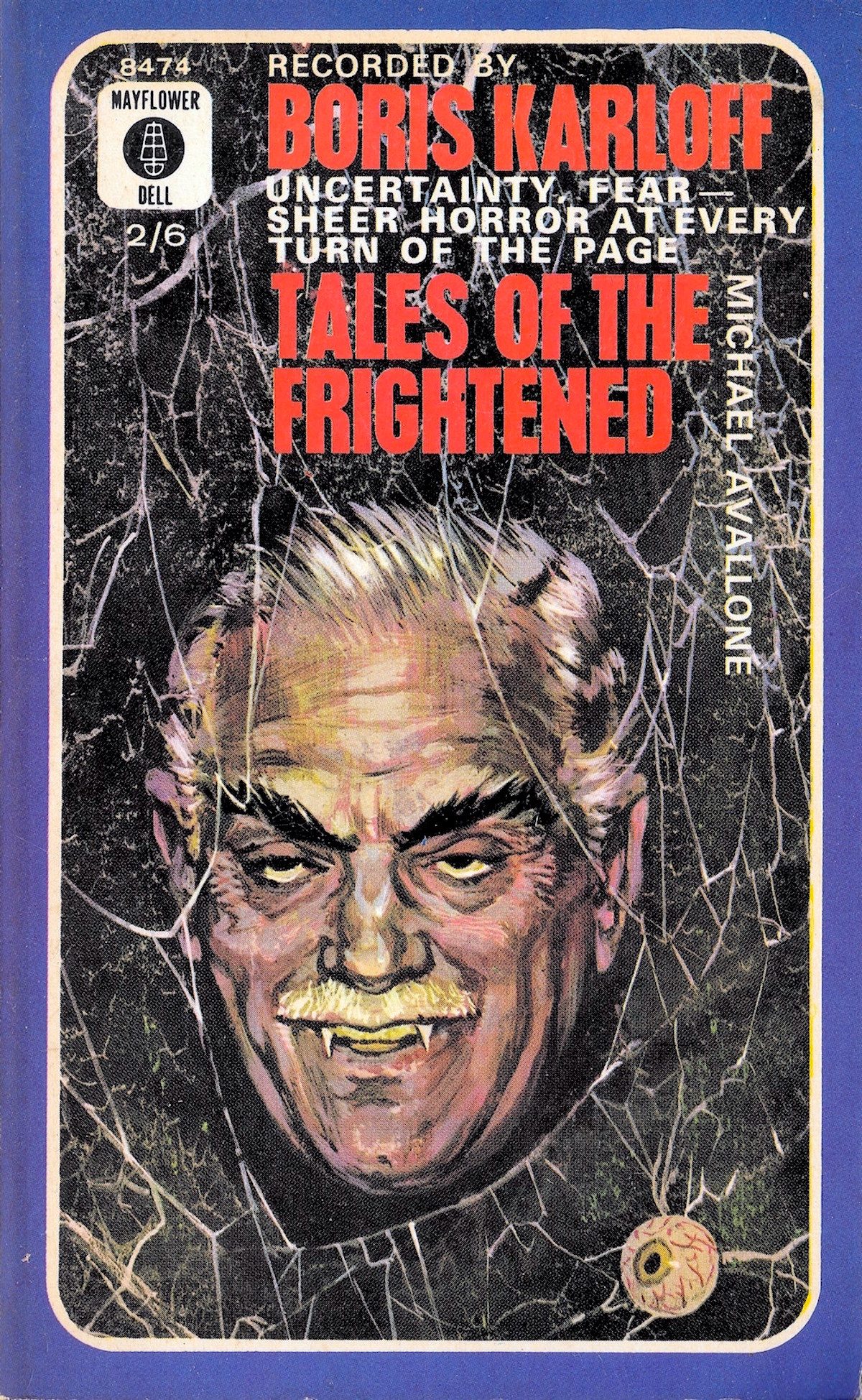

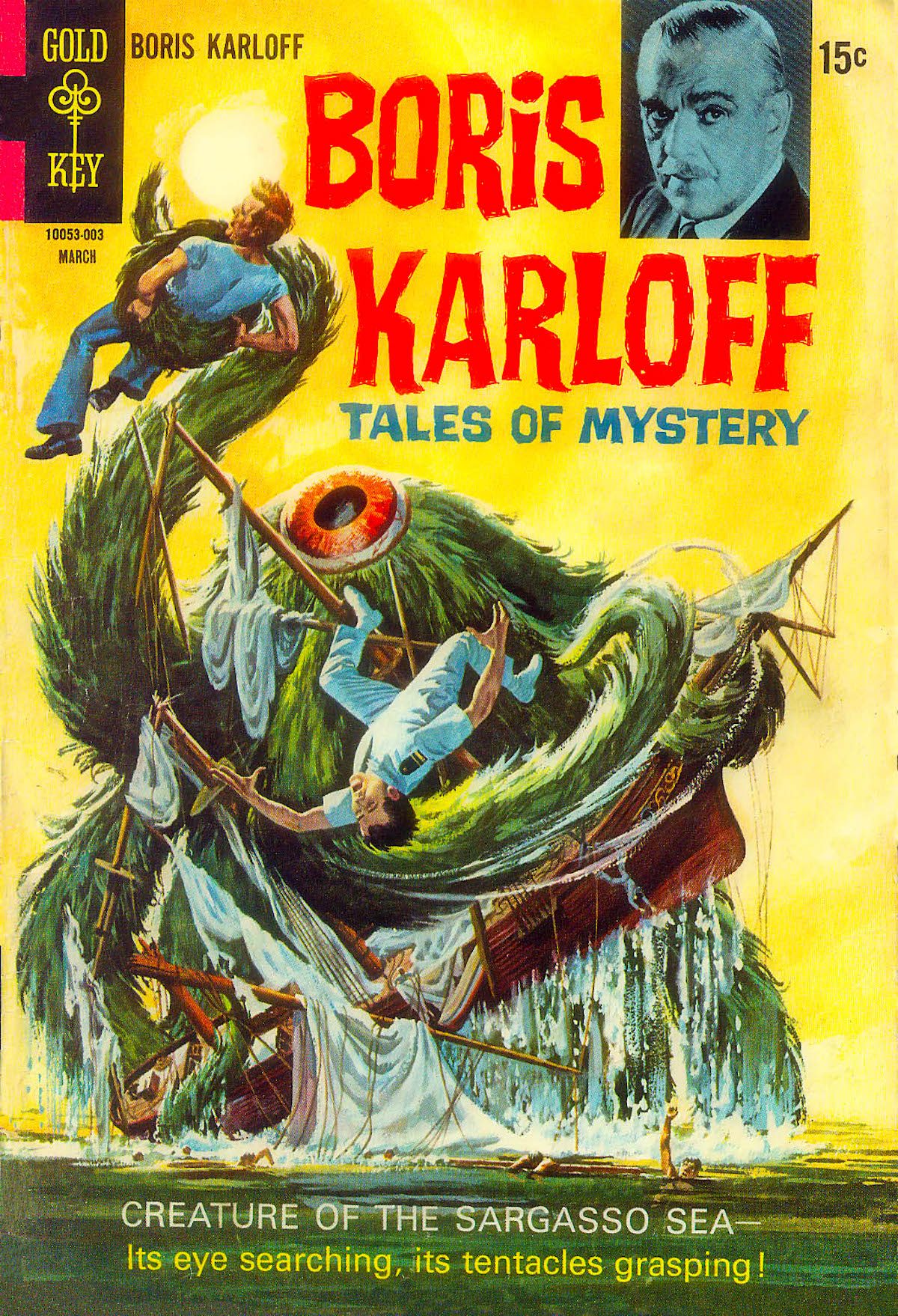

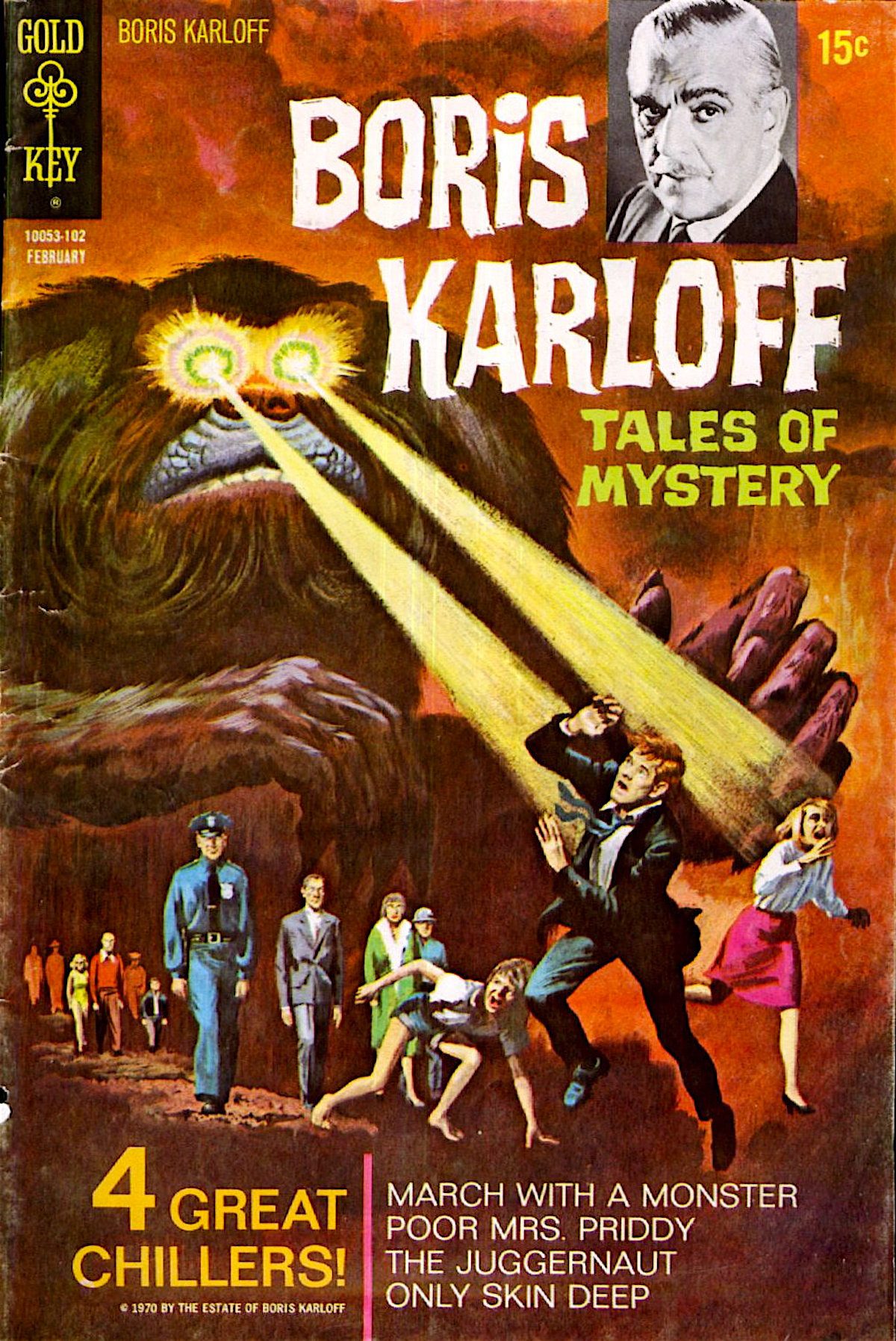

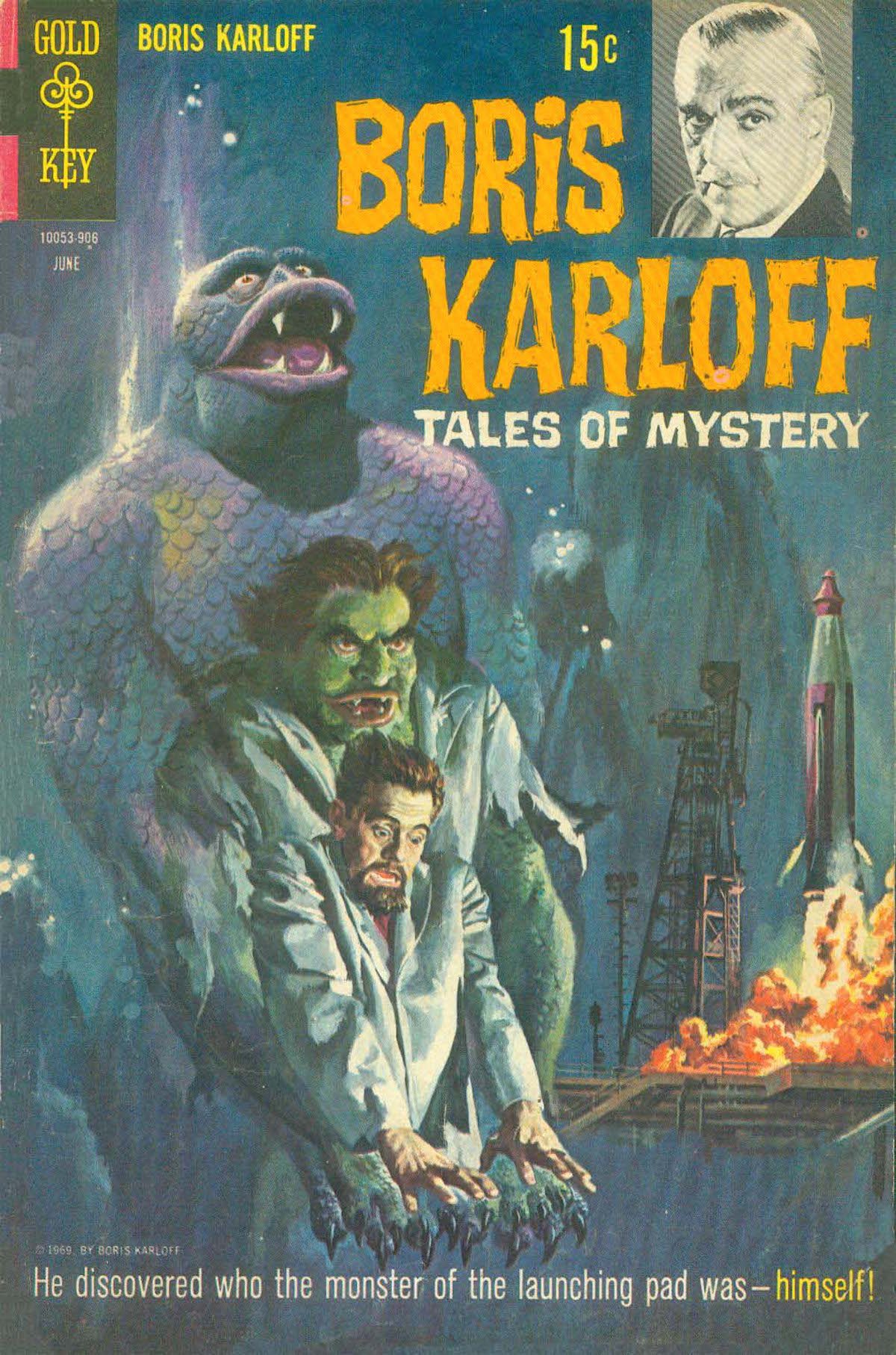

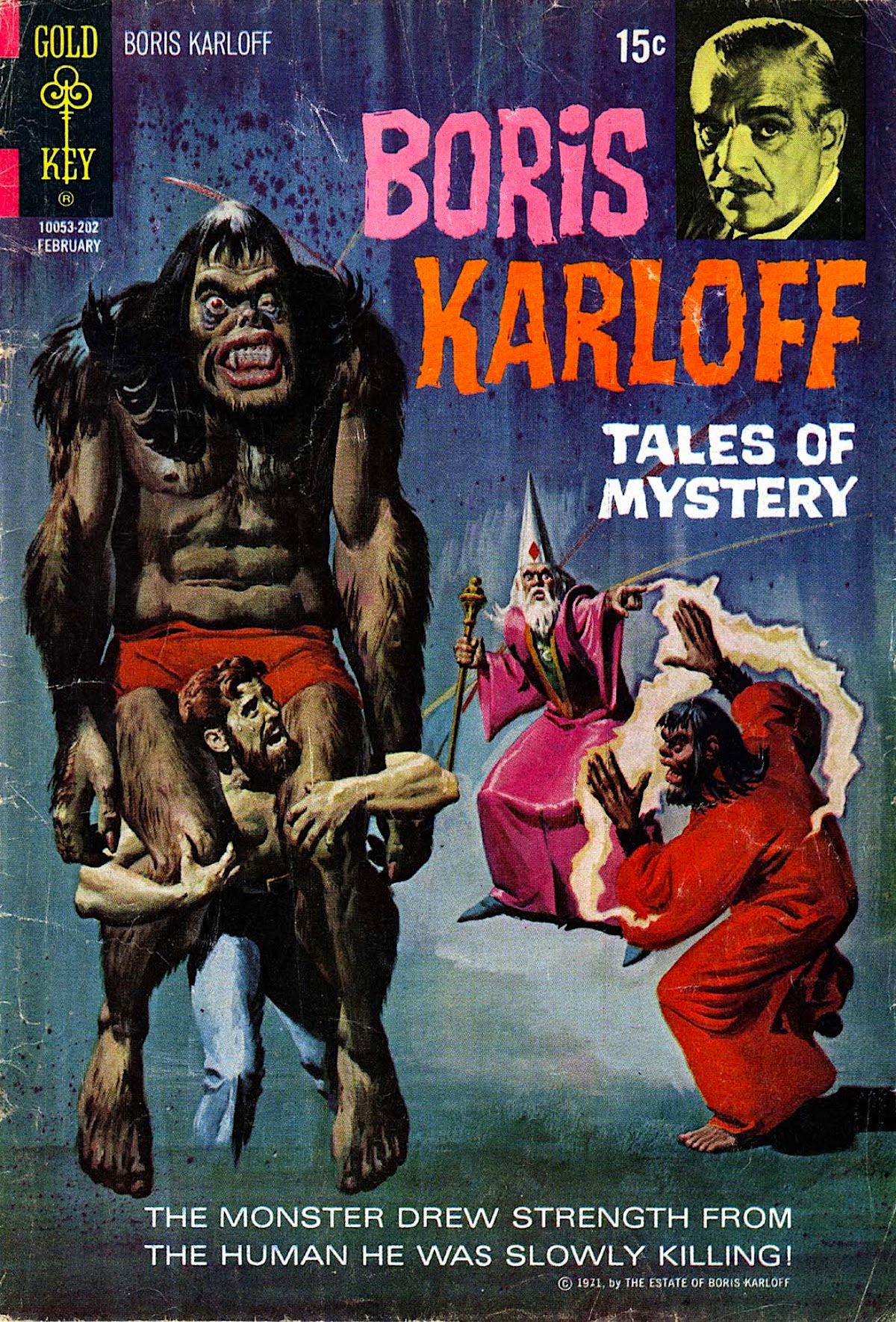

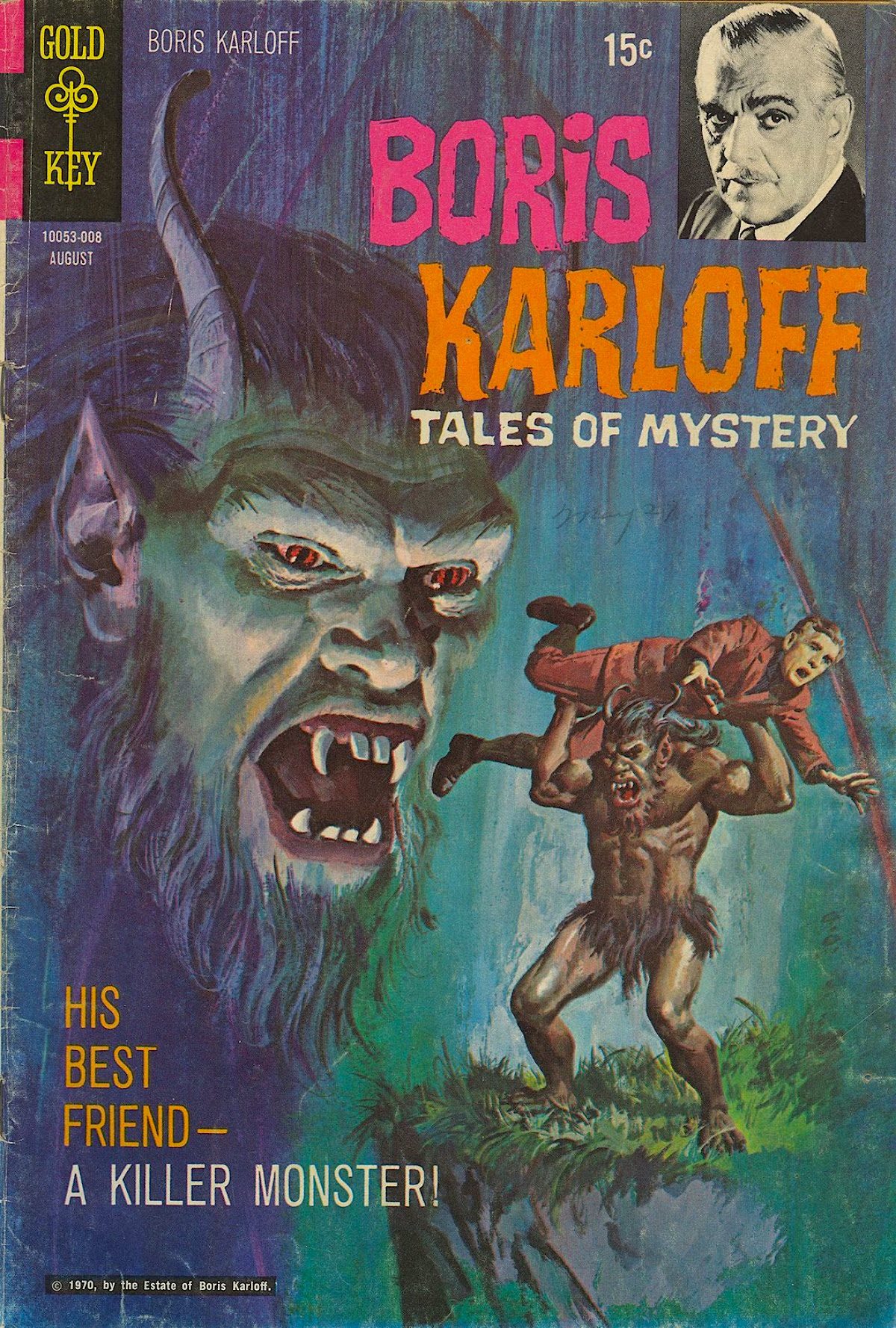

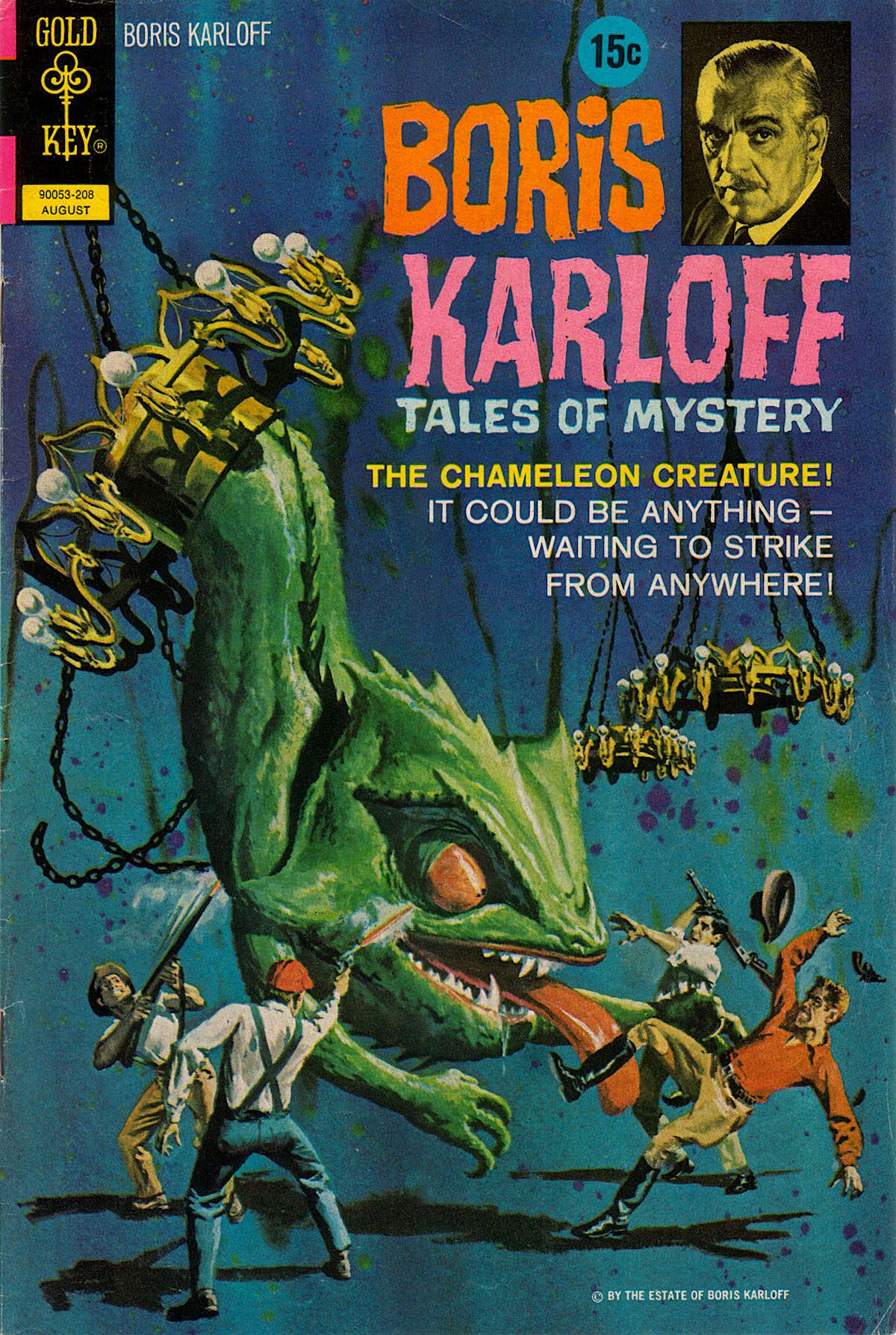

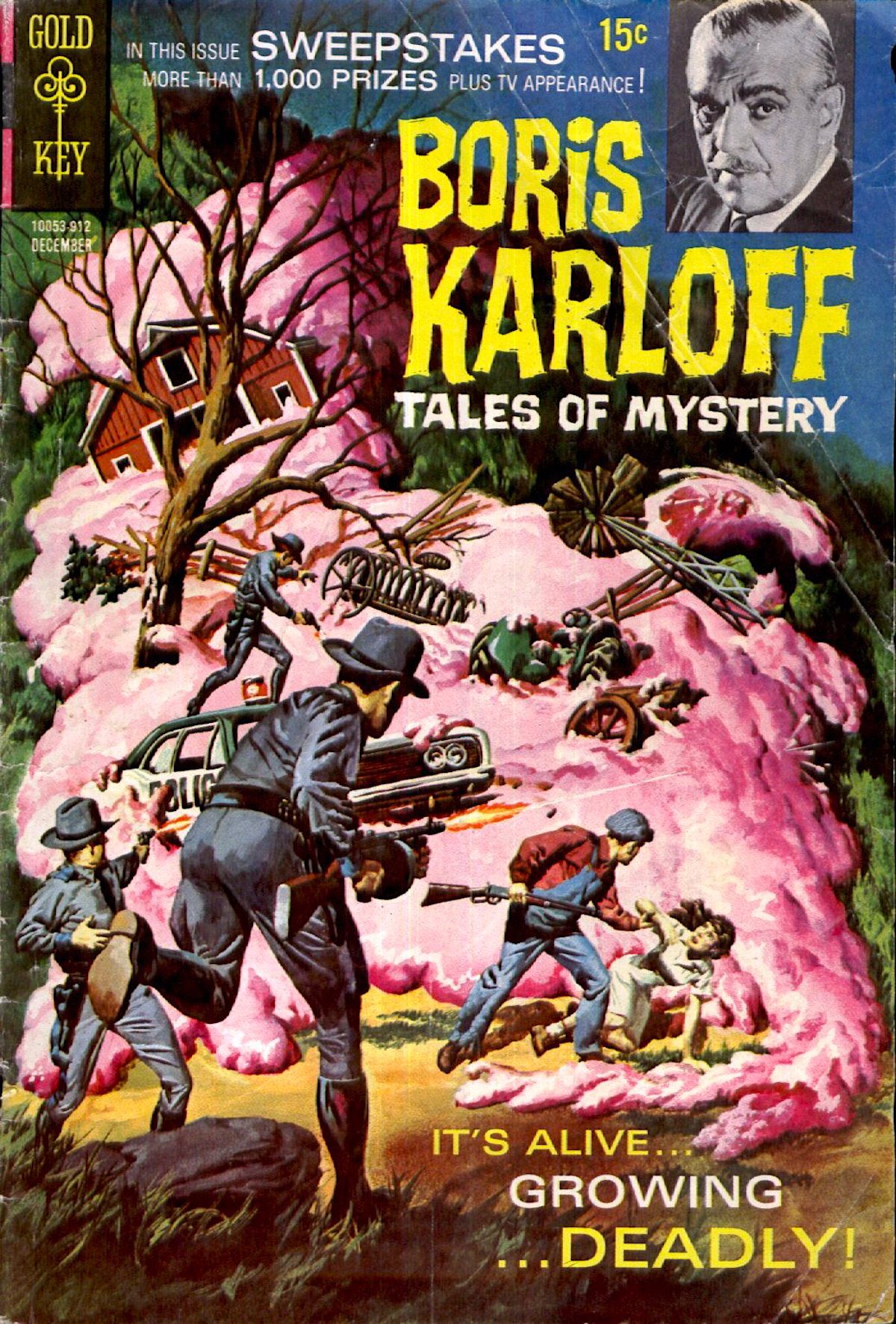

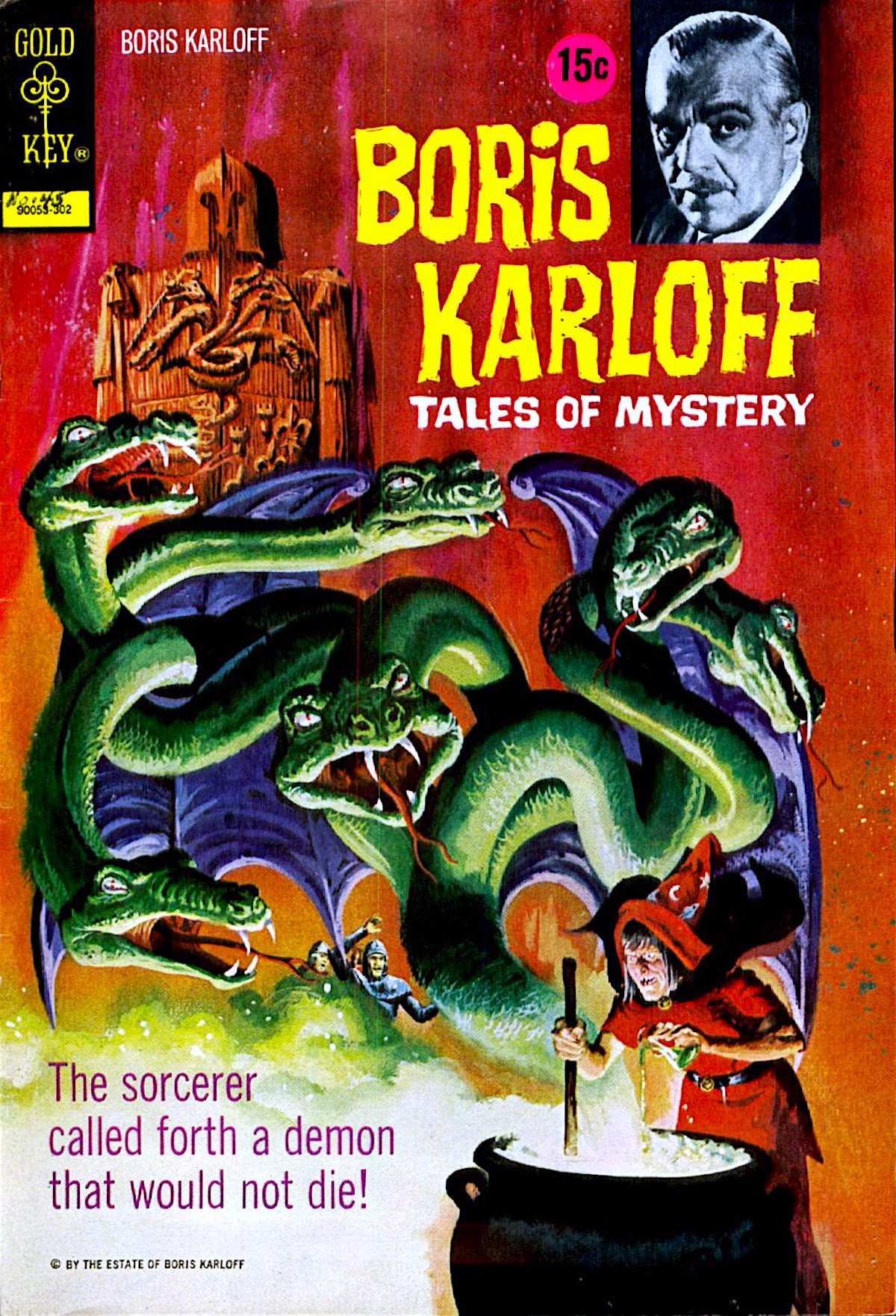

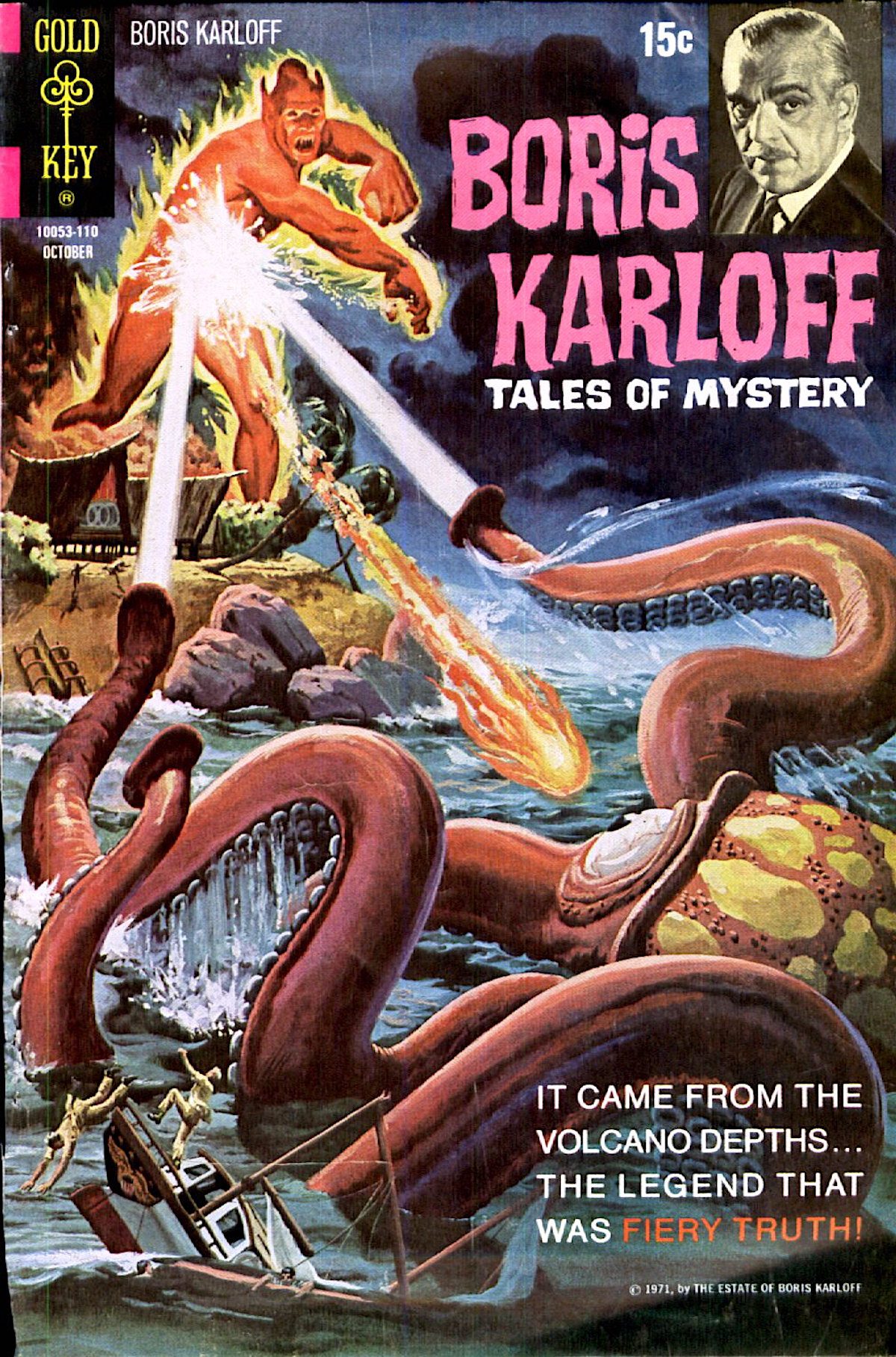

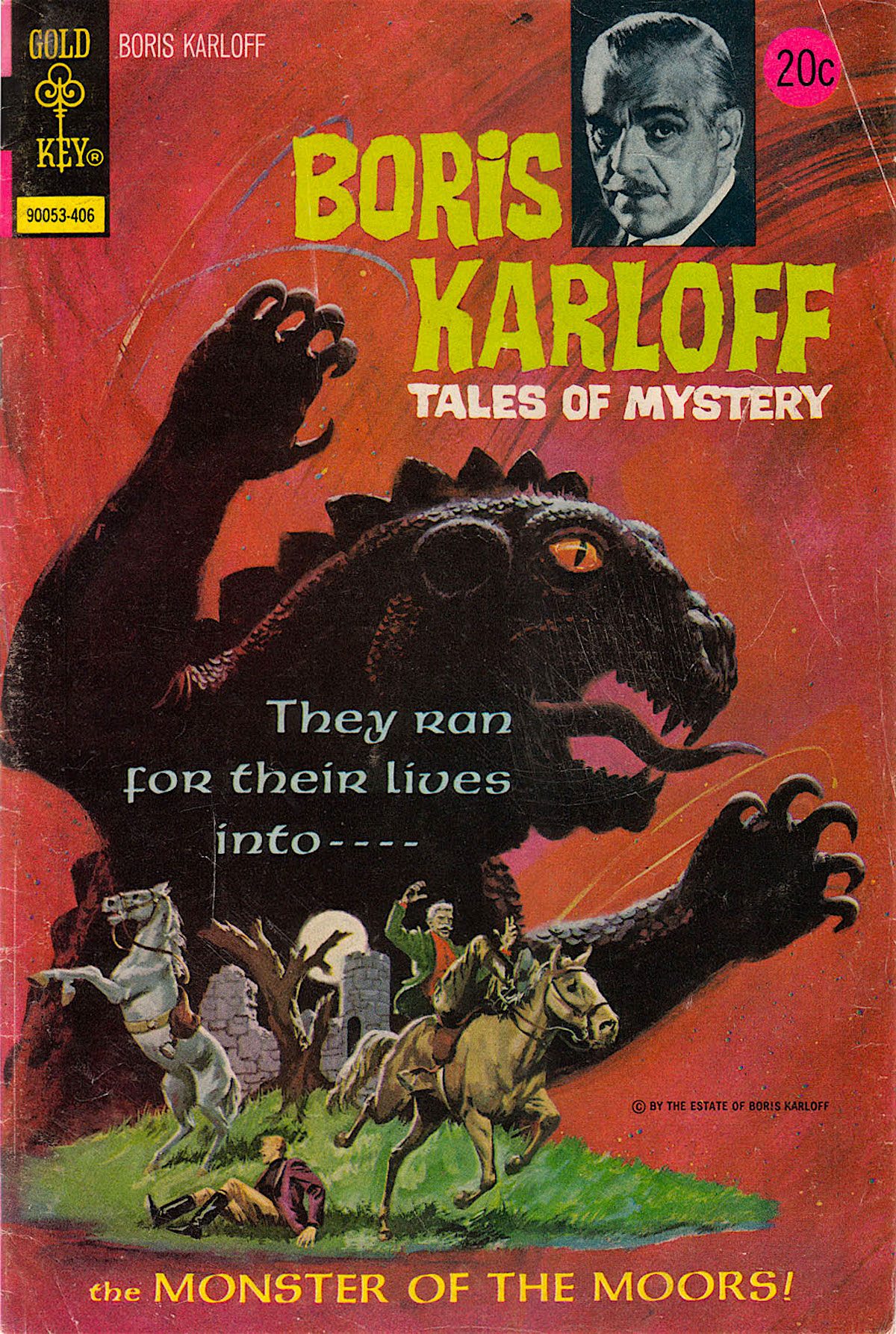

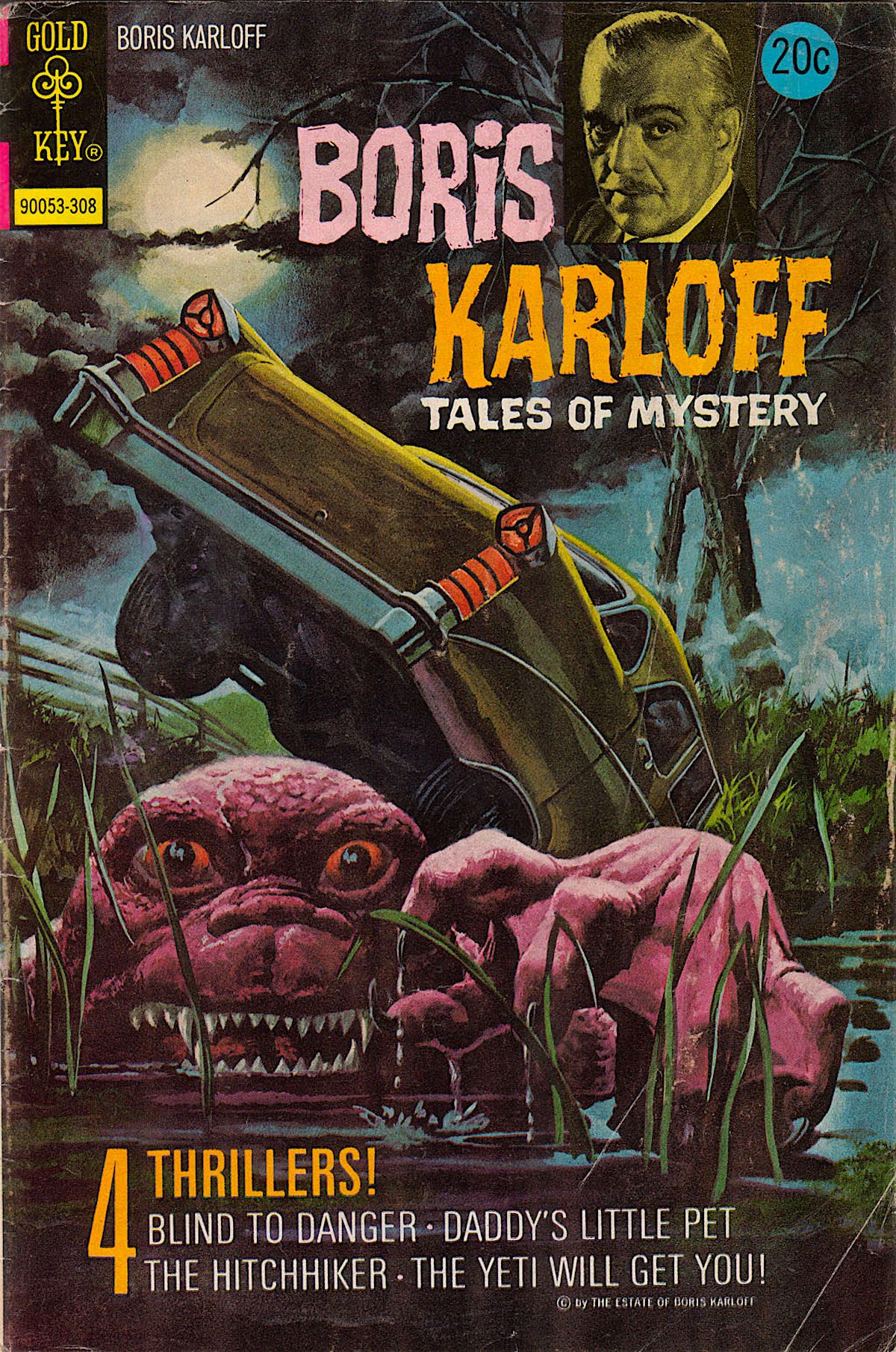

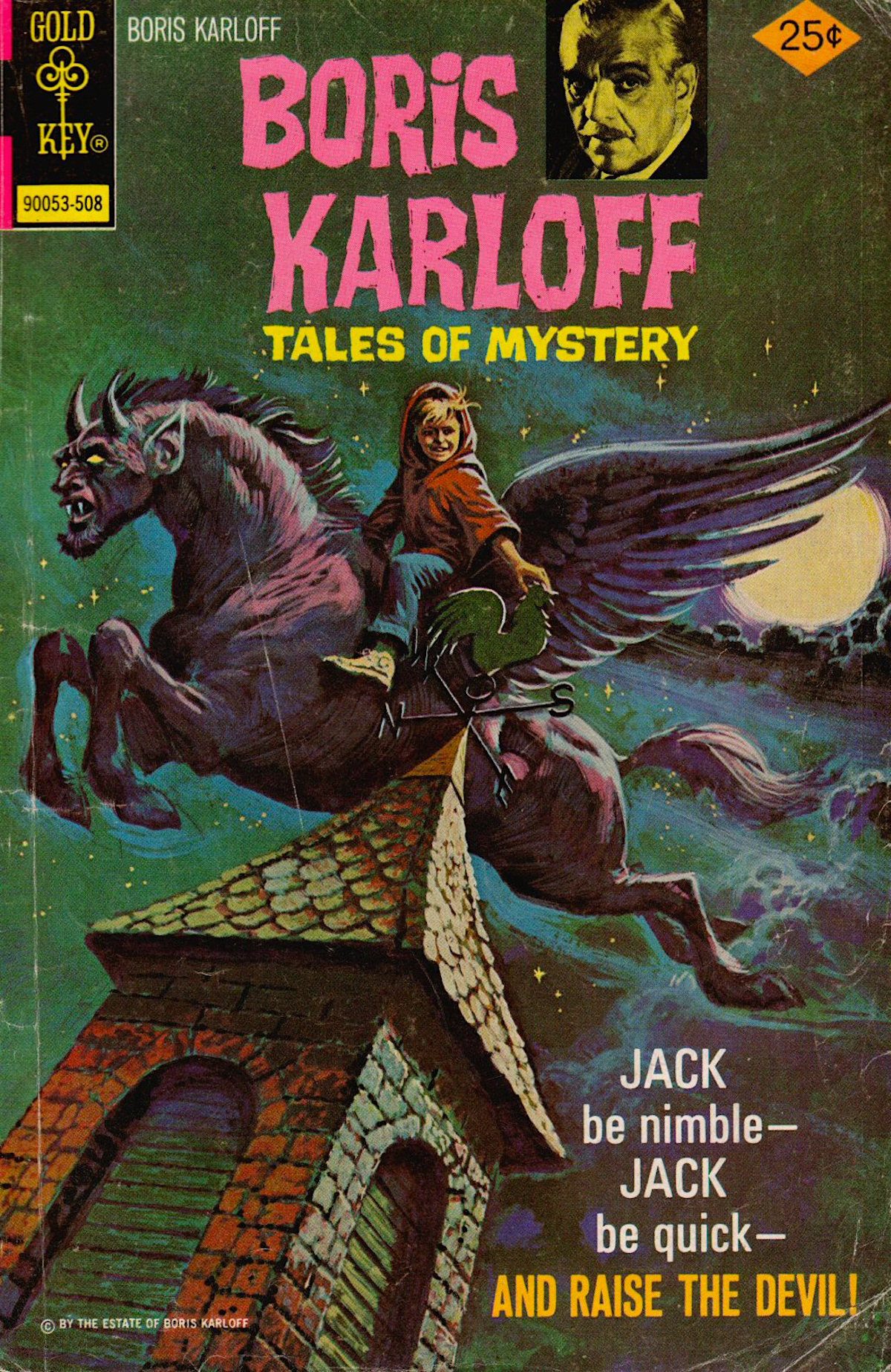

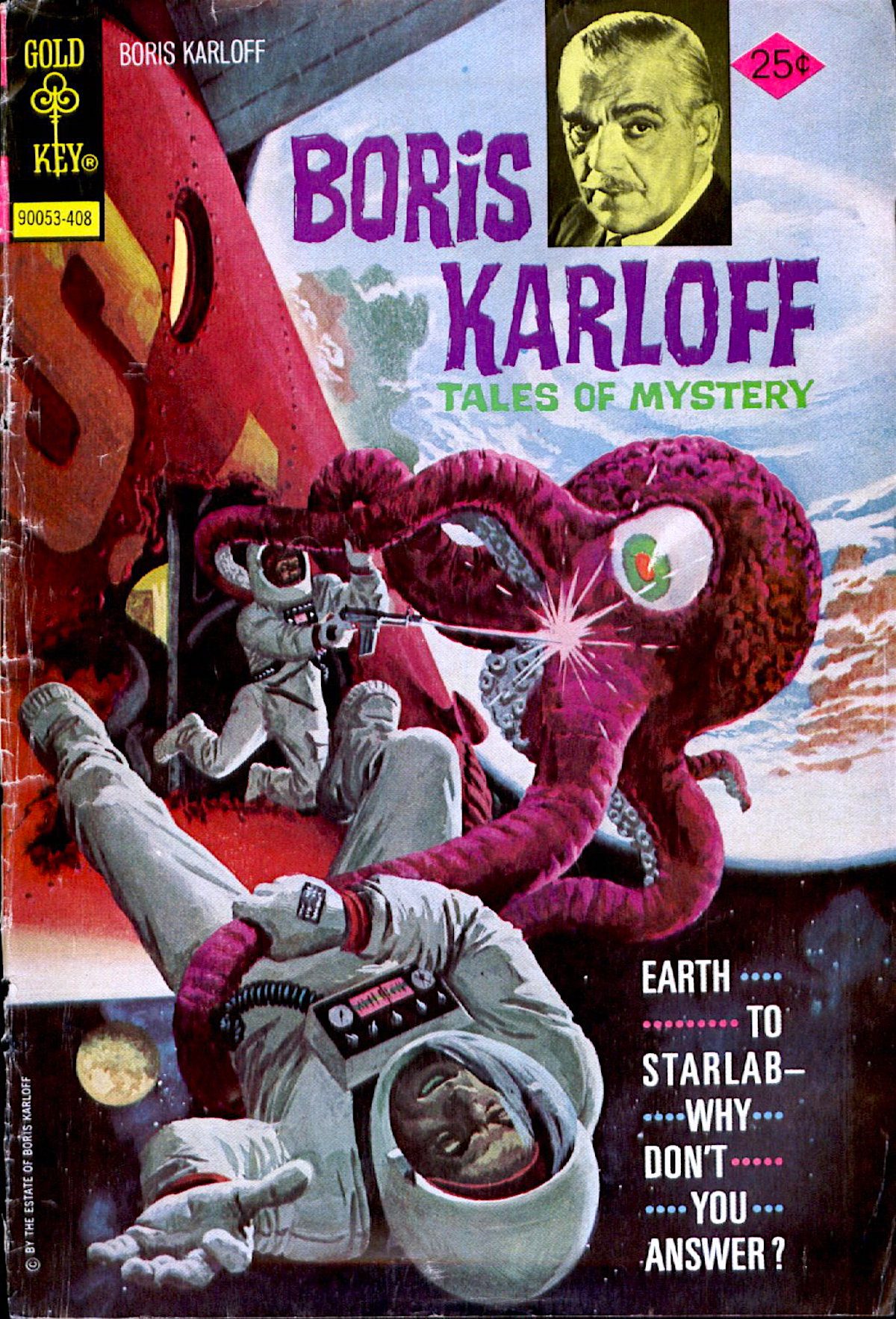

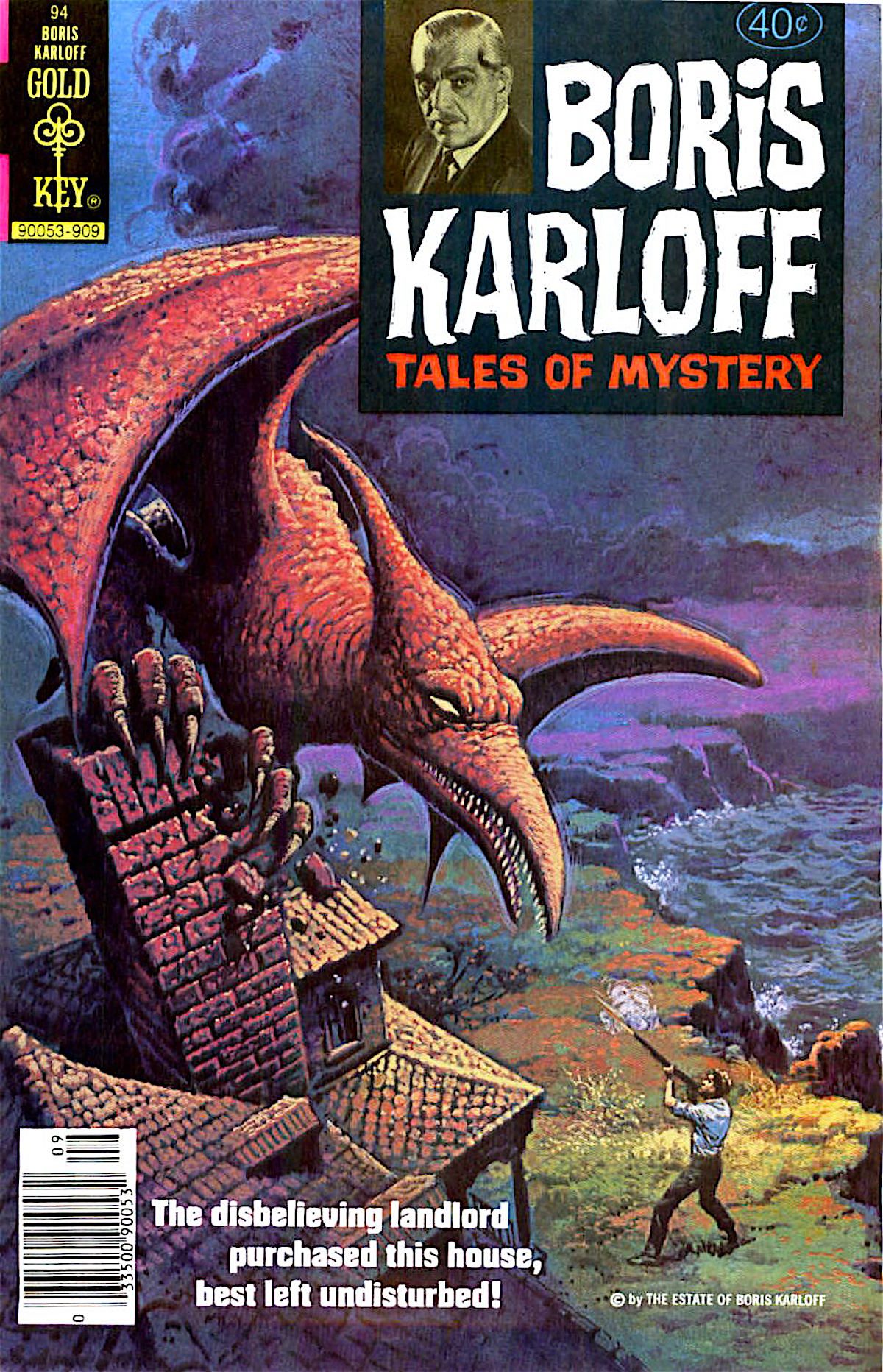

Apart from horror movies, Karloff leant his name and image to a wide selection of other projects–books, TV shows, adverts. In the early 1960s, the comic book series which came off the back of Karloff’s TV series Thriller. When the show was cancelled, publisher Gold Key re-titled the comic as Boris Karloff’s Tales of Mystery in 1963. It was published long after Karloff’s death in 1969, until the early 1980s.

H/T WikiCommons and Monster Brains

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.