“Human beings have never, it seems to me, enjoyed being reminded of their idiocy, and the English are vulnerable in these days of decline that they react against it more fiercely than ever.”

– Lindsay Anderson on Britannia Hospital

The omens weren’t good.

Lindsay Anderson was having anxiety dreams. Nightmares. He woke confused, unable to thread the stories together or understand what they revealed (if anything). In one he left his camera in a pub. The woman behind the counter had it. Then there was a film being made. Vague speech by an actor. Who was speaking? What were they trying to tell him?

The following morning he woke-up (sweating) from a dream where he was escaping (something) on a boat (somewhere) in Bristol. His friends the actresses Rachel Roberts and Jill Bennett were there. Making a film? Is it Rebecca? Running down a corridor (chased?) into a yard giggling.

Inner turmoil bubbling to the surface. Anderson once wrote in his journal:

Nobody realises what a mess of loneliness and inadequacy I am inside.

He had just had a bruising from the critics over his production of Alan Bennett’s dark satire The Old Crowd (1979), which critics loathed and audiences found outrageous. The film was about class. It opened with a crack in the ceiling of an old house where a middle class couple had invited friends to their house-warming party. The serving staff were uncouth and menacing. A sequence of toe-sucking (between Frank Grimes and Jill Bennett) caused considerable offence. The drama examined the rot of the class system and its inevitable decline. The crack spread across the ceiling (“like a bang in the street”) until the whole thing came crashing down.

There was a plan to make The Old Crowd into a movie but like most movies in Anderson’s career it never came about. Anderson then had a brief role in Chariots of Fire. He planned to direct his latest crush Frank Grimes in Hamlet. His dreams continued to unnerve him. In November 1980, he heard the news his friend Rachel Roberts had committed suicide in Hollywood.

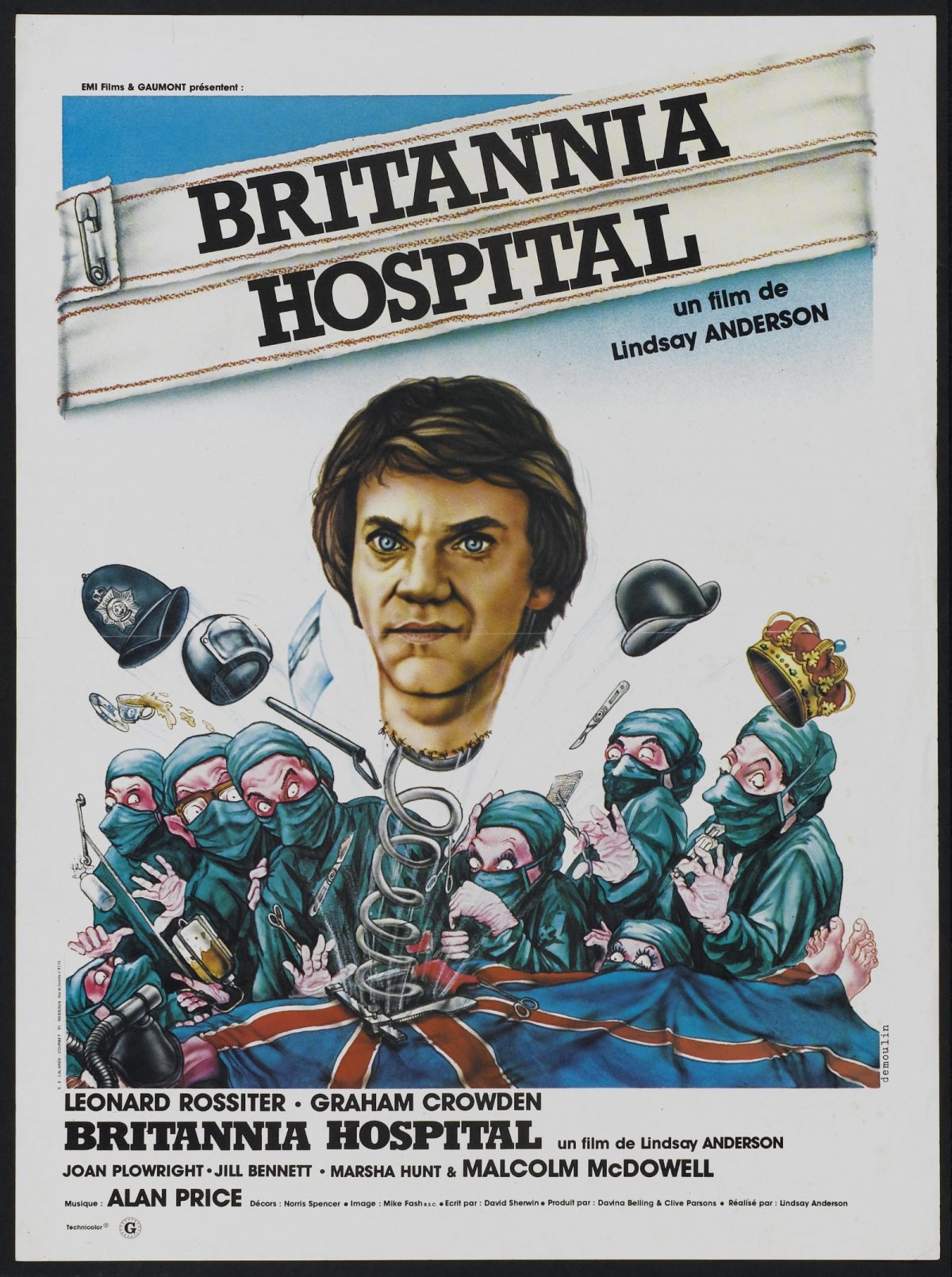

The new year, brought hopeful plans for a new movie. The final part in the trilogy of films that started with If… (1968) and continued with O, Lucky Man! (1973). This new film was an epic satire on the state of the United Kingdom – its corrupt unions, its insane Royalty, its oppressive class system, its oleaginous management, and evil politicians. The film was called Britannia Hospital. It was the film that almost but destroyed Anderson’s career as a film director.

Lindsay Anderson (1923-94) was a film director, theatre director, television director, a documentary filmmaker, a writer, critic, and pioneer of Free Cinema. He directed eight movies and one music documentary Wham! in China: Foreign Skies from which he was dismissed. His best movies (This Sporting Life, If…, and O, Lucky Man!), as Alan Bennett described them were “outcrops of his inner life.” Often his repressed obsession with a male heterosexual actor–Richard Harris in This Sporting Life, Malcolm McDowell in If… and O, Lucky Man! and Frank Grimes in Britannia Hospital. These actors were the source of his unrequited love–and all three were unaware of Anderson’s obsession.

It wasn’t just secret passions that inspired Anderson, he was also choosy in what he made, often rejecting more lucrative movie deals. He turned down directing more films than he ever made. This included The Eyes of Laura Mars (“a load of balls”) and E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India. Anderson was able to be picky as he enjoyed a income from one of his Aunts “a Miss Bell of Bell’s Whisky”. Yet, he spent most of his money “supporting a resident cast of lame ducks” as Bennett noted:

Sandy, his schizophrenic nephew; Patsy Healey, who had acted in his short film The White Bus and been depressed ever since. There was his mother and, for a while, his brother’s wife, and he was always on call to counsel and very often to subsidise needy friends and actors who had lost their way. I have had some credit because I gave room in my garden to one social inadequate. Lindsay played host to half a dozen with no credit at all, nor, I imagine, much thanks. And he made nothing of it. He was a good, compassionate man presenting to the public a face that was scornful and reproving and hungry for publicity while doing untold acts of private goodness.

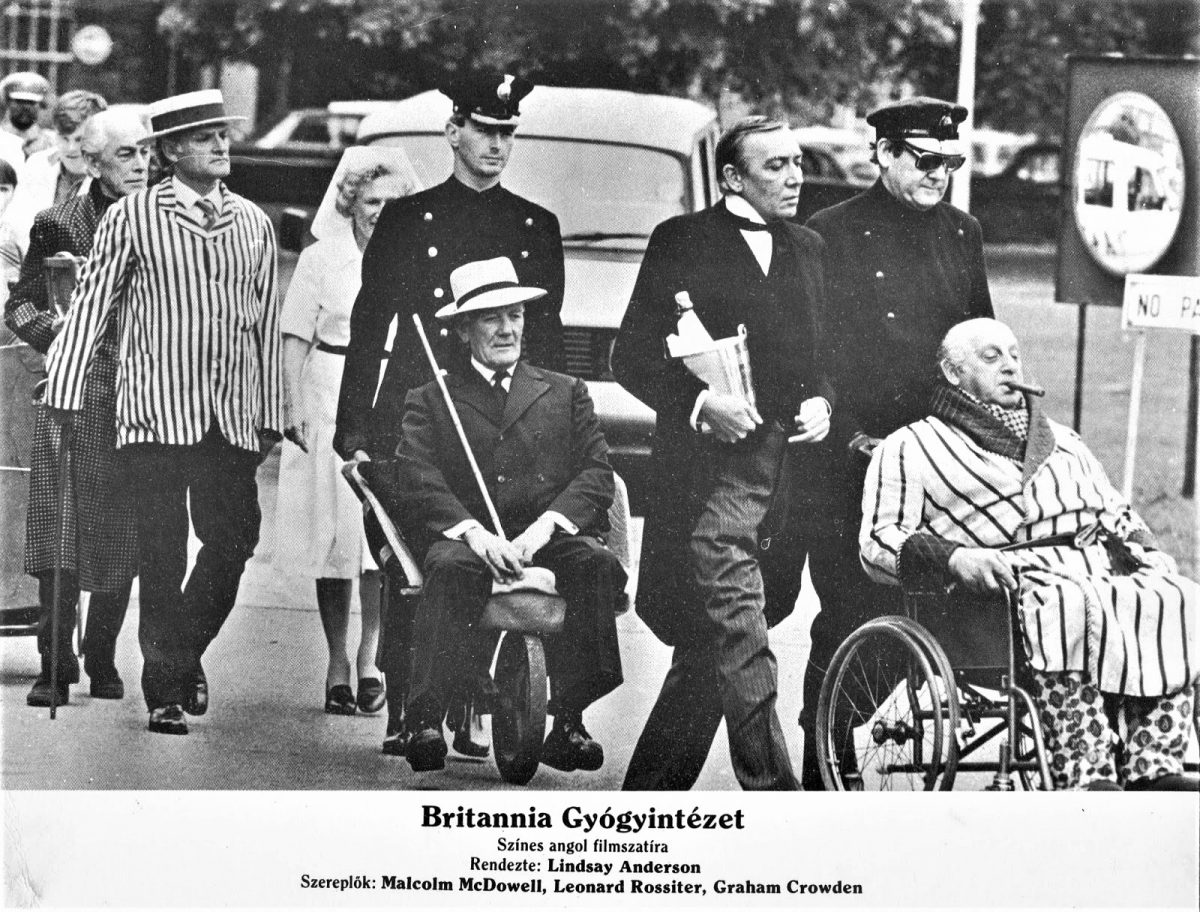

Anderson’s inspiration for Britannia Hospital came as a front page story in the Daily Mail sometime during the Winter of Discontent in 1979. Striking unions had brought the country to a standstill. One trade union representative called “Battling Granny” was barring private patients from the Charing Cross Hospital in London. Anderson who was an anarchist, found the situation “grotesque” and thought the unions were lacking basic humanity. People were dying in hospital corridors, mountains of rubbish filled city streets, while the dead were left unburied. He wrote a scenario around a Royal visit to a hospital were the unions were on strike. He passed this onto his long-time collaborator David Sherwin, who had written If… and with Malcolm McDowell O, Lucky Man!.

The script became what Anderson called an “epic satire” on the whole structure of British society. In a letter to Christopher Isherwood, Anderson discussed some of his intentions in making the film:

I’m in the middle (at least I hope it’s the middle) of shooting Britannia Hospital, another foolhardy attempt to hold the mirror up to the English visage, and there to show such black and grained spots…With laughter too, but of that mocking kind which the English don’t really like too much. The conception, which seemed to everyone to be a jolly, modest romp, has grown and grown into another attempt at epic satire–I just don’t seem to be able to restrain myself in that area, although I know perfectly well that it’s the hardest thing to bring off artistically, and never very popular, however well one manages to do it. Human beings have never, it seems to me, enjoyed being reminded of their idiocy, and the English are vulnerable in these days of decline that they react against it more fiercely than ever. (Particularly, of course, our old enemies, the Liberal bourgeoisie!)

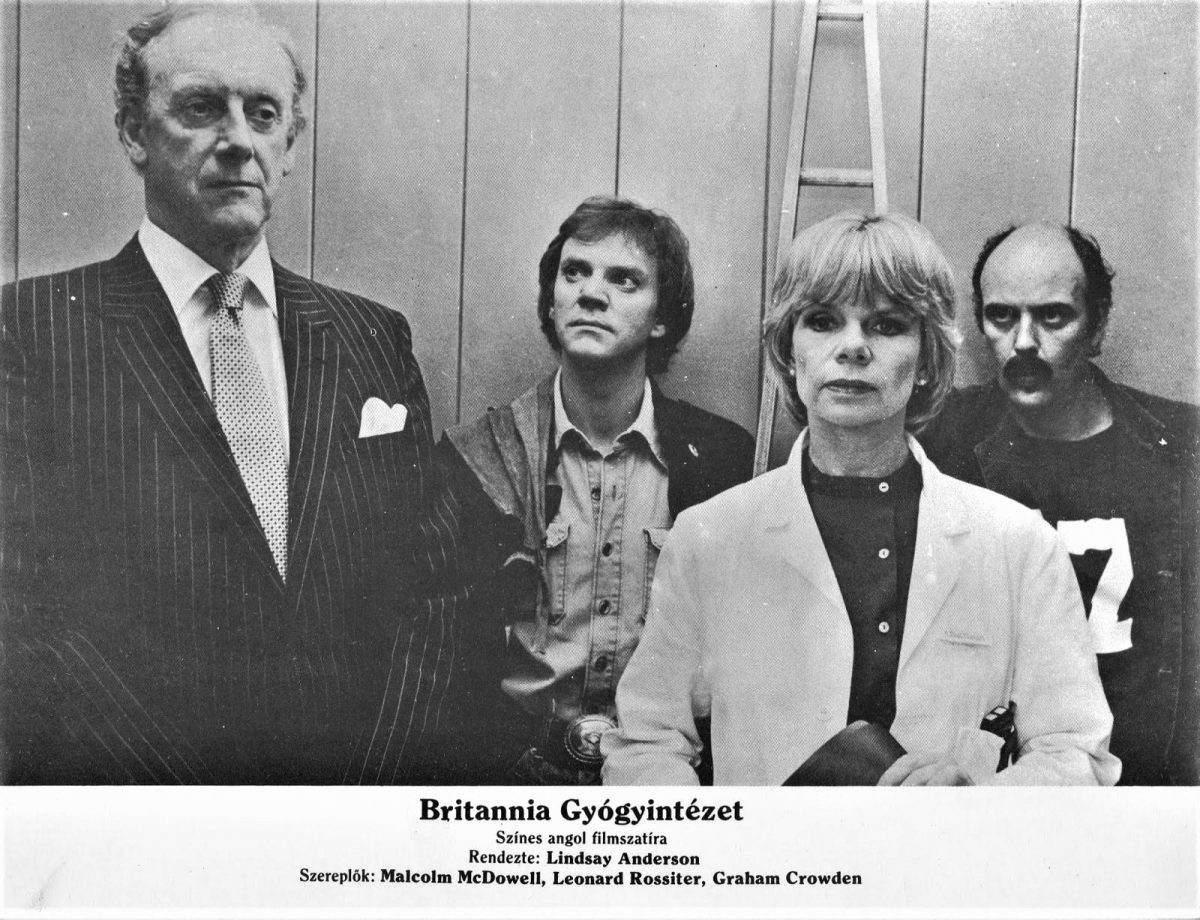

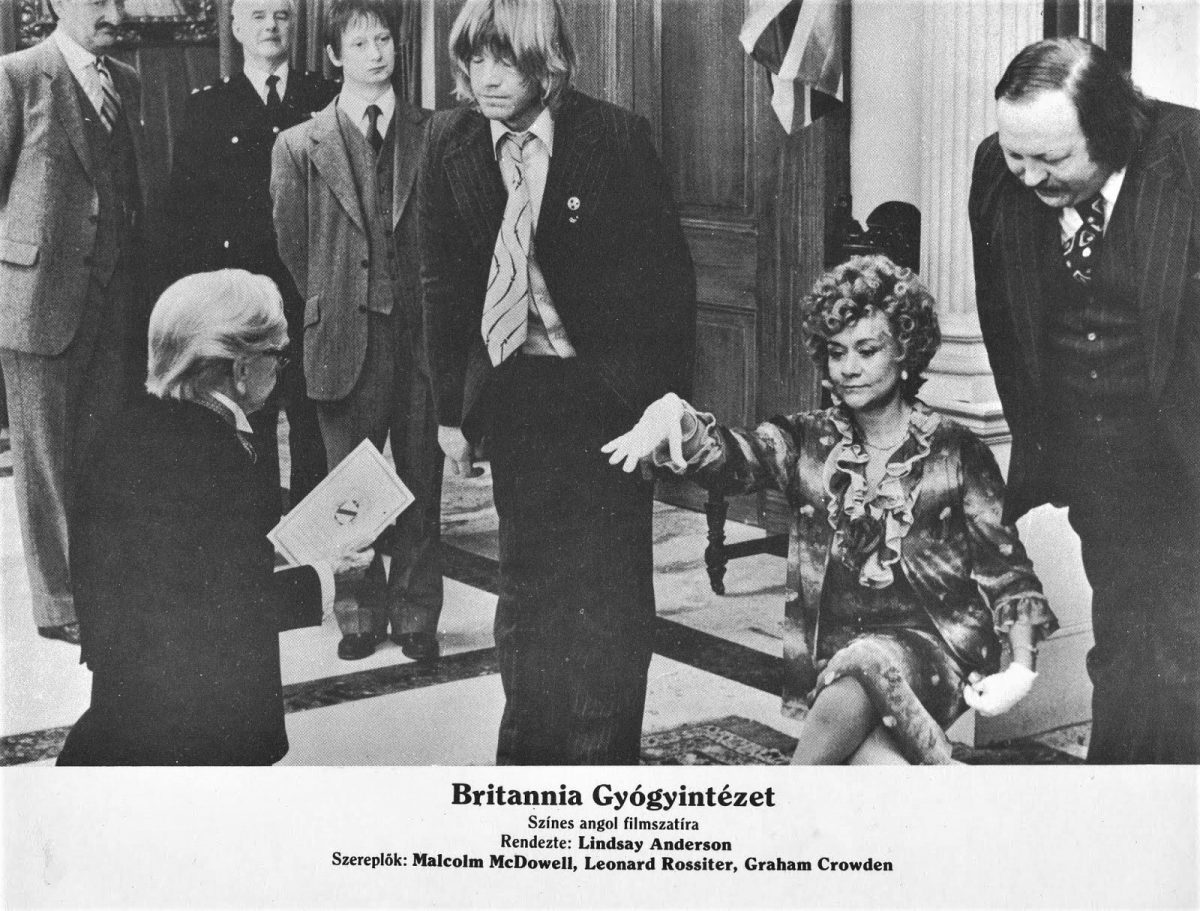

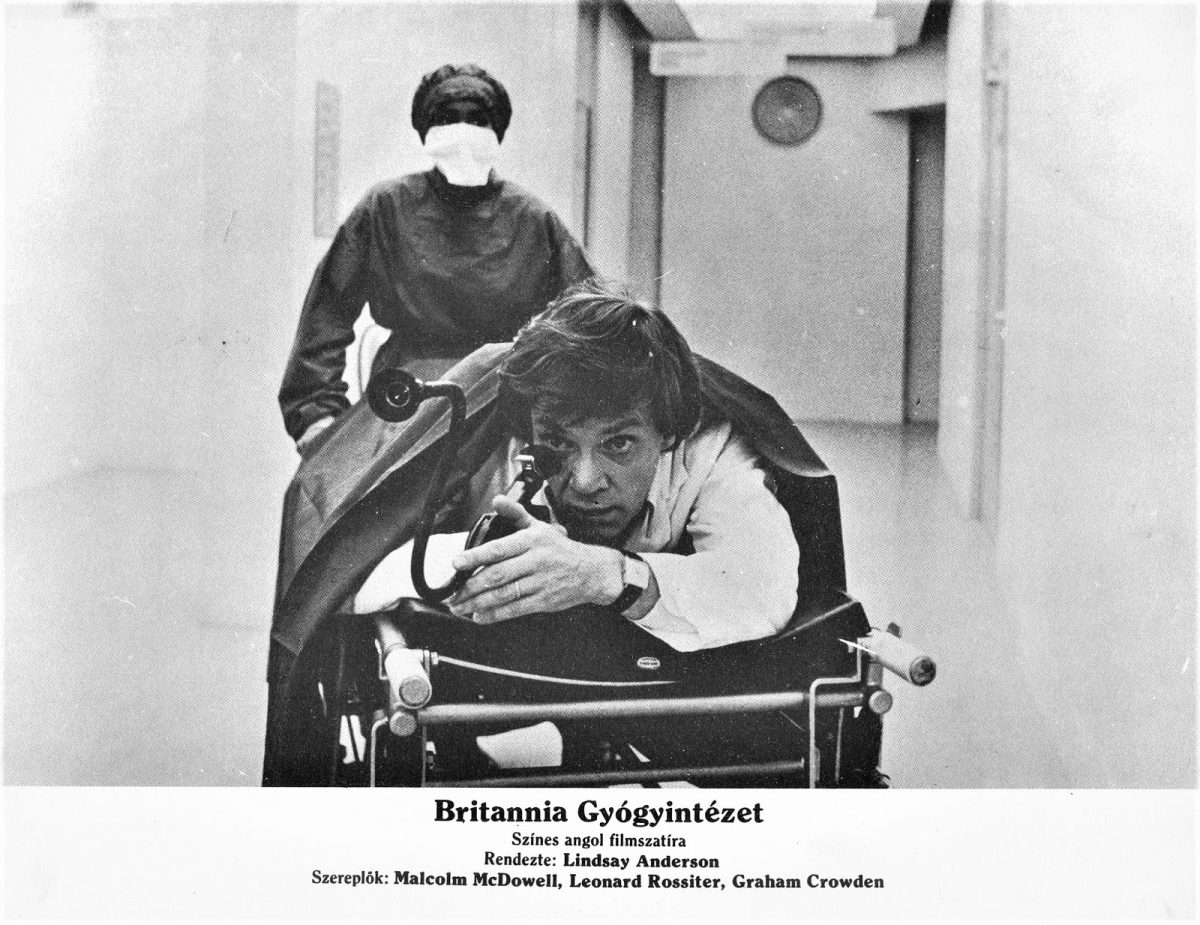

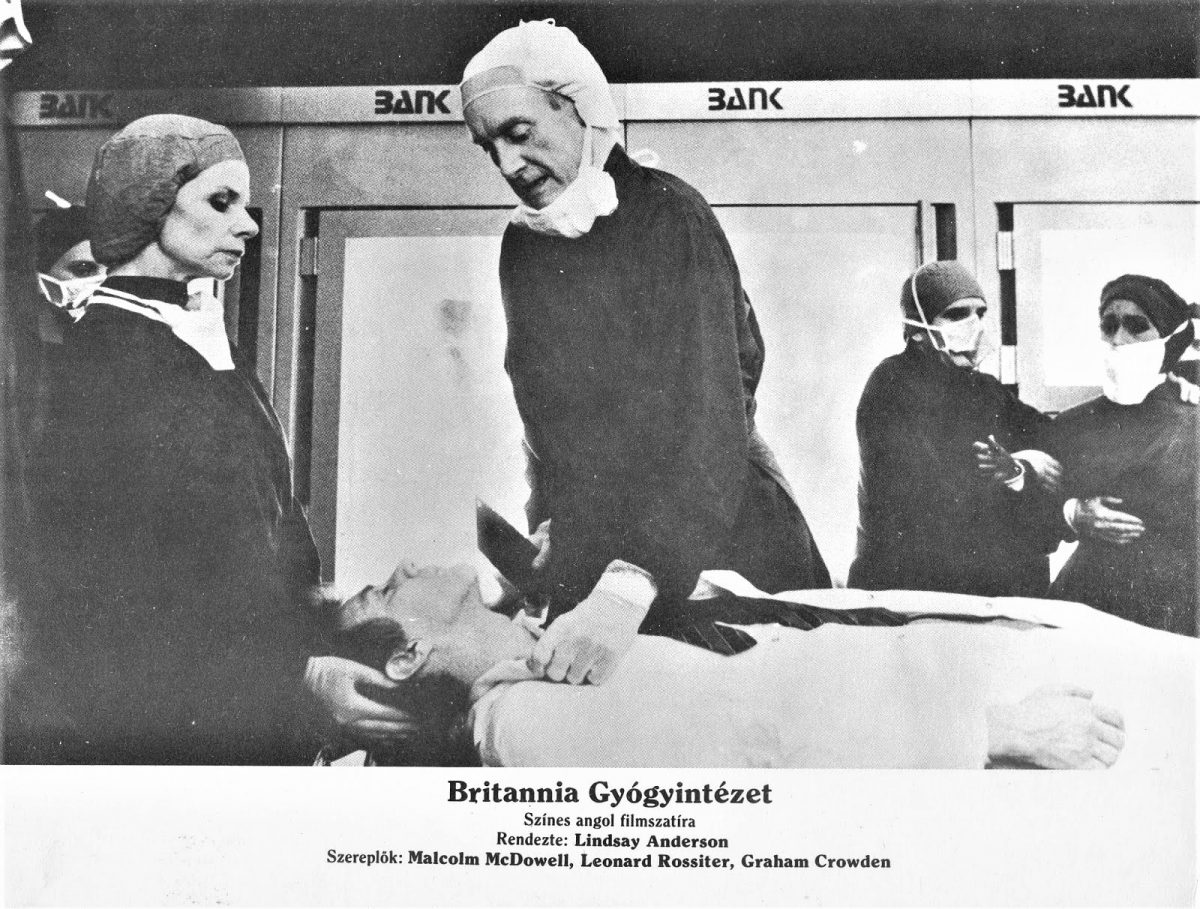

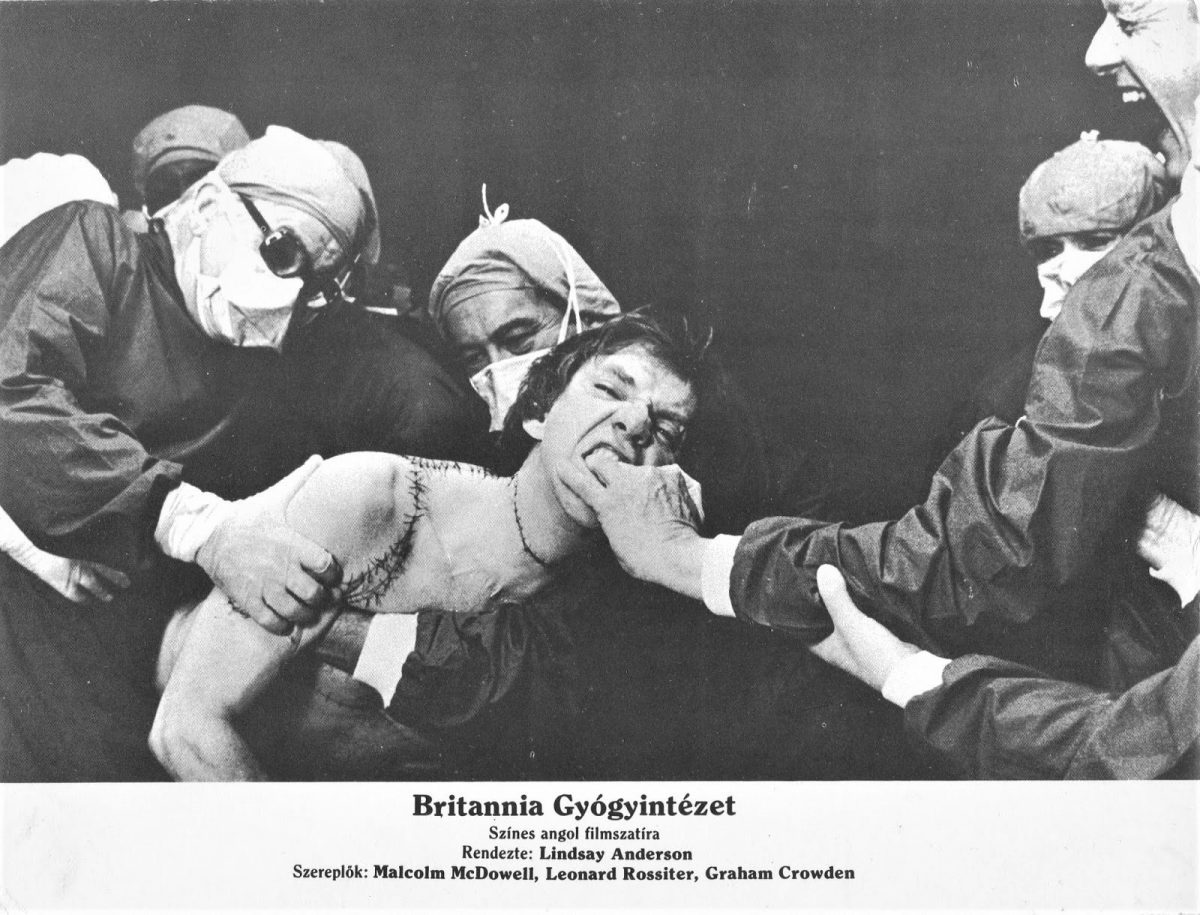

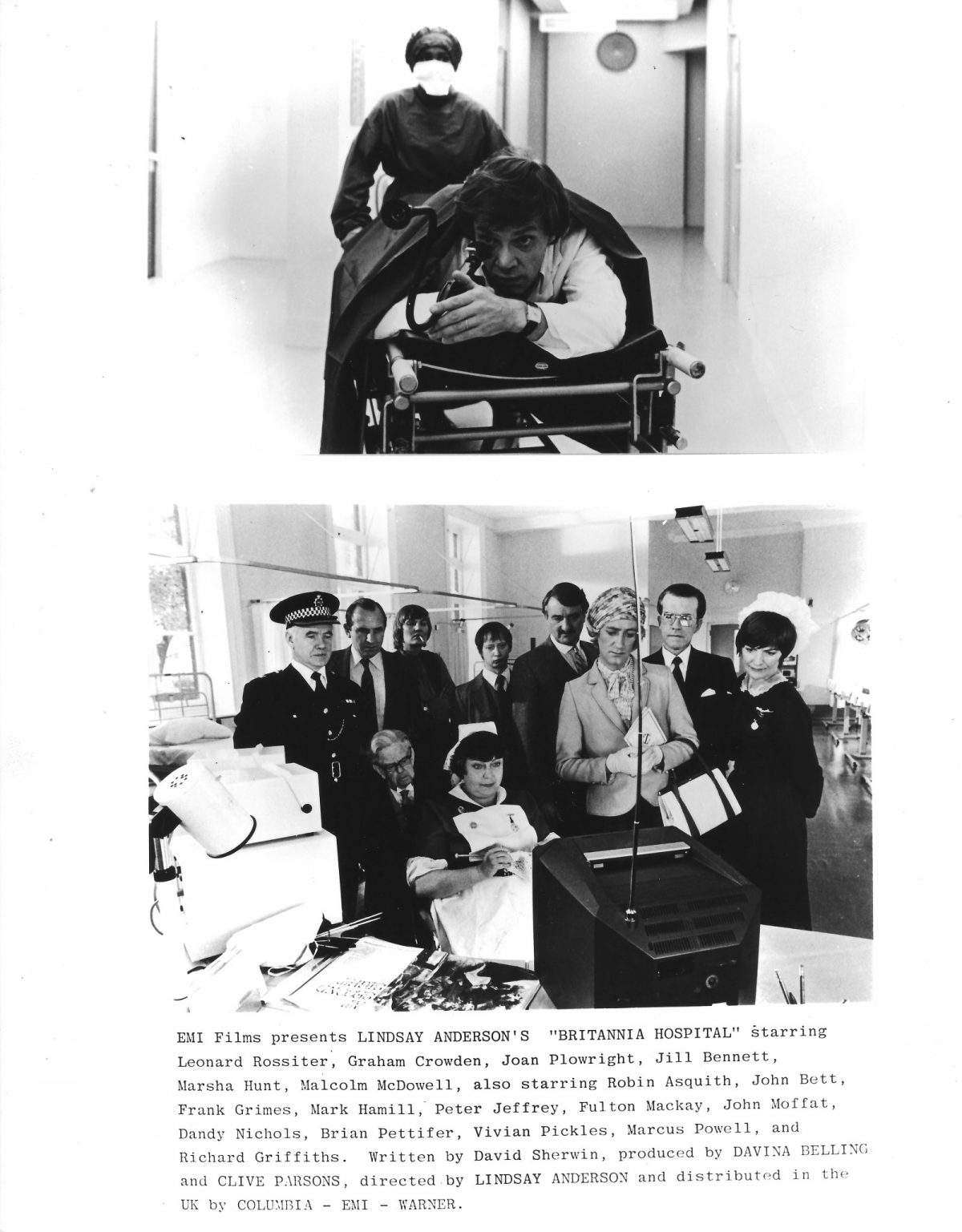

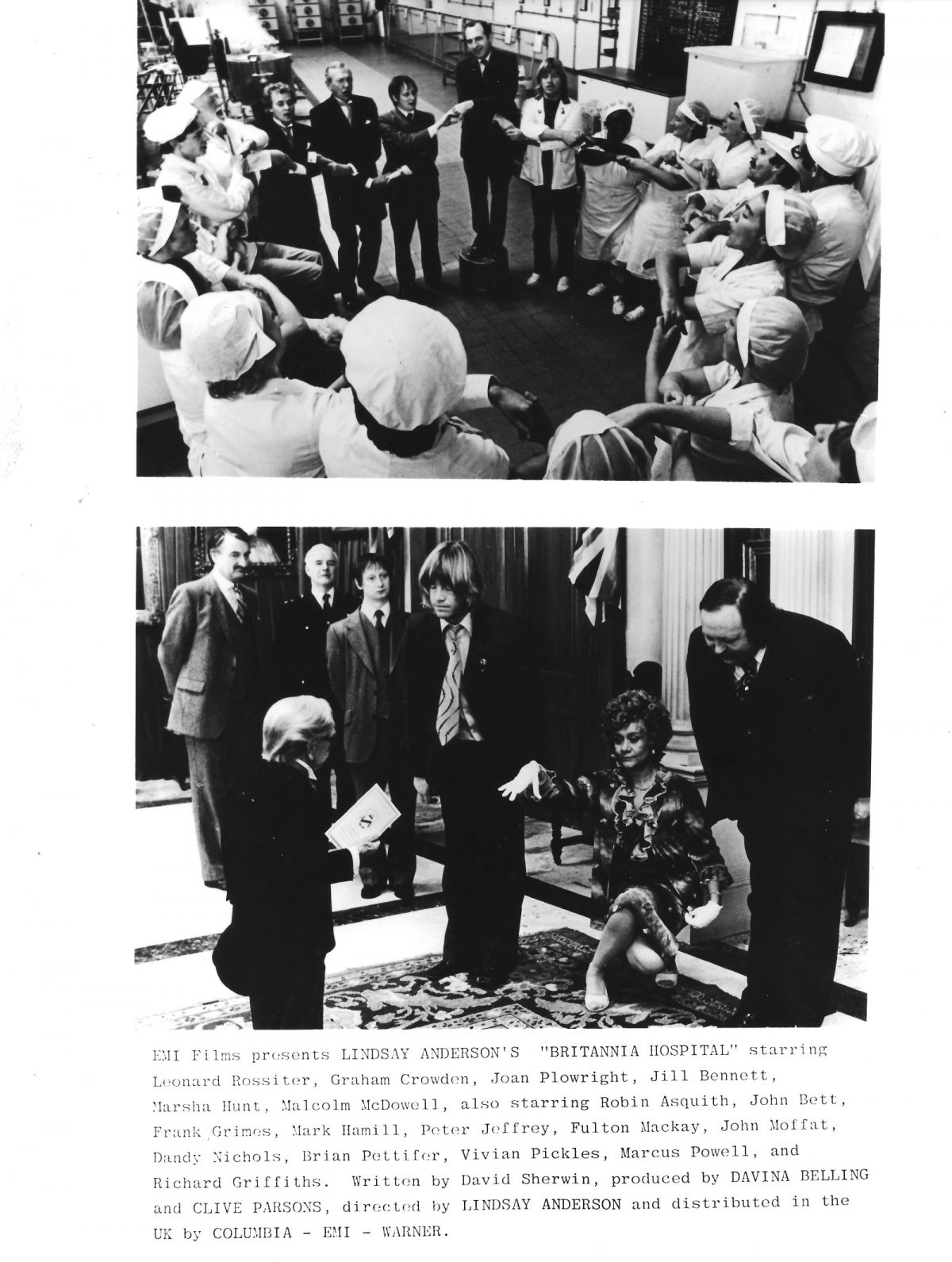

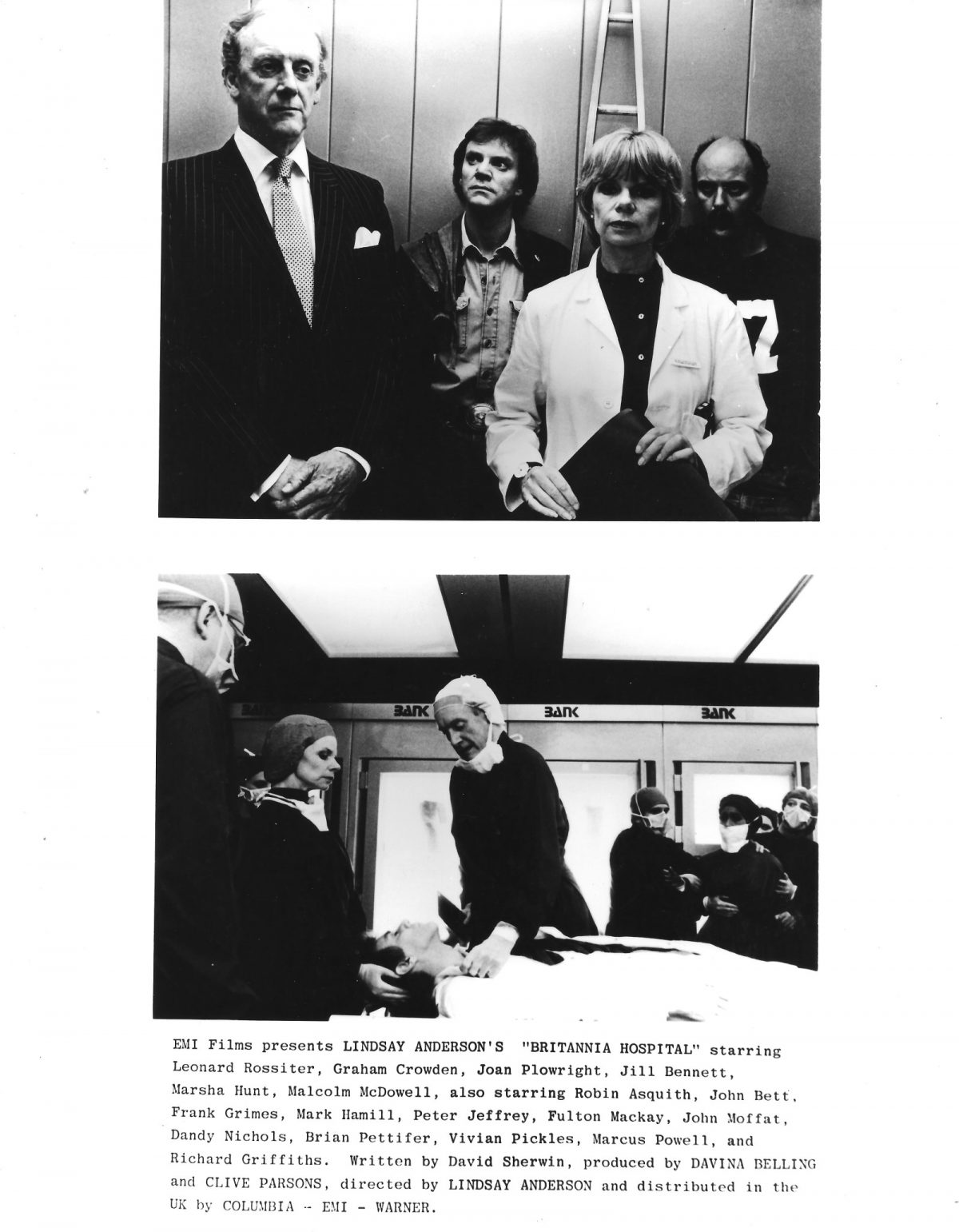

Britannia Hospital is celebrating its 500th anniversary. The Queen Mother and a Japanese ambassador are to open the hospital’s new Millar Centre for Advanced Surgical Science. This celebration is threatened and almost derailed by industrial action. Striking staff picket the hospital objecting to the private treatment of an African dictator. Into the midst of this comes Mick Travis (Malcolm McDowell) the lead character in If… and O, Lucky Man!. Travis is an undercover reporter wanting to expose the inhumane experiments being carried out by Doctor Millar (Graham Crowden) at his new Centre for Advanced Surgical Science. Millar had briefly featured in O, Lucky Man! where he transplanted human heads onto pigs. Now he has created a monstrous new lifeform Genesis–a transhumanist creation. An artificial intelligence–part microchip and part human.

Encouraging all this madness are the media, who promote hate and fear, and encourage violence.

If Britannia Hospital was released now, it would probably find an audience with those who question the role of the media in promoting political agenda. It would also strike a chord with those who have concerns over a transhumanist Fourth Industrial Revolution which organisations like the World Economic Forum claim will liberate people through technology (“You will own nothing and you will be happy”) rather than enslave them with a new feudalism where the Internet barons will be the overlords.

Unfortunately, Britannia Hospital was released at the end of the Falklands War, when jingoistic fervour was at a high following Britain’s victory over the Argentinians in a war for an island thousands of miles away.

When the film was premiered at the Cannes Film Festival the British delegation walked out en masse in protest against the film. The British press irreparably damaged the film, lambasting its perverse attack on the British class system, its Royalty, and unions. The movie was deemed an embarrassment, offensive, and a poor imitation of a Carry On film–one without any jokes.

Alan Bennett agreed. He thought Britannia Hospital “just isn’t funny” and Anderson had under estimated the sophistication of his audience, a reason for this Bennett explained:

….was that [Anderson] didn’t watch much television. He never appreciated the regular diet of not always mild subversion and social criticism that was still the staple of television drama; police brutality or municipal corruption were taken for granted by a TV audience (or were certainly nothing fresh) so they were not easy to shock as Lindsay wanted to shock them. But it wasn’t because they were jaded, just more discriminating than he gave them credit for. He thought he was saying something bold and new in Britannia Hospital but even in 1982 he wasn’t – not in England anyway. One of his Polish friends said: ‘It’s the best Polish film I’ve seen in a long time.’

The French, the Germans, the Poles, and even the Argentinians loved Britannia Hospital. They appreciated the satire as they had, in one way or another, experienced some of the events depicted on screen.

Anderson was unbowed. In an interview with an irate Richard Cook for the NME, he said his film was “an attack on institutions” and “an attack on human folly.”

This idea was reinforced in an interview with E. Rampell in “Revolution is the Opium of the Intellectuals” where Anderson said Britannia Hospital was an anarchist film, with the intention of encouraging the audience to mistrust “institutions, power, the instincts for power within us.”

[Britannia Hospital] puts the responsibility squarely on the individual to develop first the intelligence and the moral awareness by which alone Man can control his destiny. Obviously, the signs in the world around us that this is possible are not numerous.

If only he had included more fart jokes….eh?

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.