“You are judging by social rules and finding crime. I am considering an elemental struggle, and finding no crime – just grim, primeval danger”

— John Wyndham, The Midwich Cuckoos

Instructions for a DIY Narrative on the Life and Work of John Wyndham (abbreviated version)

Contents:

1 x science-fiction author John Wyndham

1 x science-fiction author Brian Aldiss

12 assorted facts

1 plausible narrative

Overview: Writers filter their stories through the prism of their experience.

Instructions: Wash hands and prepare on a clean dry surface.

Fig. One: Brian Aldiss said John Wyndham’s sci-fi novels were “cosy catastrophes”. It was was a petty comment intended to belittle.

Fig. Two: Wyndham’s novels were never cosy. At best, they were dark tales of speculative fiction examining how life continues to exist–in all its mundane desperate ways (See Fig. Four)–against monstrous forces attempting to destroy it.

Fig. Three: The ideas came from Wyndham’s own experience.

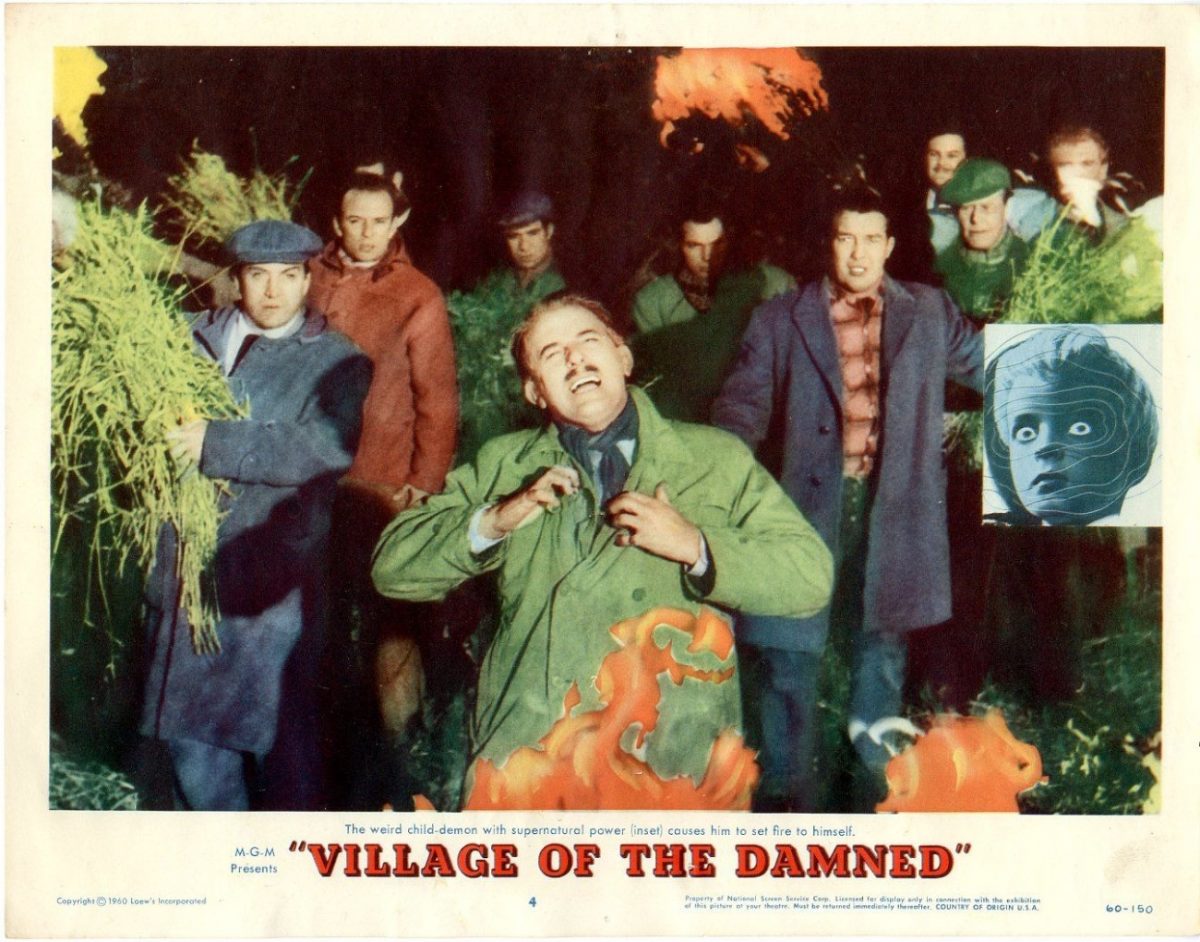

Fig. Four: During the Second World War, Wyndham was first employed on fire watch. In the dark cloudless night bombs fell. Bursts of flame (bright, greedy) grew like “some monstrous fruit”, or rather some monstrous vegetable, or killer plants lashing out while down below the terrified populace scurried blindly in the dark.

Fig. Five: This idea of maintaining some structure of normal life included a woman offering herself to one of the central character in The Day of the Triffids, as long as he will protect her and her children. In another scene, a crowd of frantic blind people fight over canned food, one woman cradles her prize thinking it some tinned savoury to eat, unaware it is detergent.

Fig. Six (See Fig One): After his time on fire duty, Wyndham worked as a censor, reading combatants’ letters home, discovering intimacies, while blue pencilling indiscretions.

Fig. Seven: Then he worked as a cipher. Writing codes, translating codes. Reading details of numbers dead, numbers wounded, while in a murmuring office environment. A half-pint, a chat, and a sandwich at lunchtime, a cup of tea at four. Life went on, but the horrors were all around.

Fig. Eight: Wyndham finally joined the army. What was once removed was now first hand. Nothing imagined equalled the horror of war.

John Wyndham Parkes Lucas Beynon Harris (the excess of names would come in handy later on) was born on 10th July 1903. He began his career as a writer in the late 1920s supplying short science-fiction stories to American magazines. He wrote under the names John Beynon, John B. Harris, and Lucas Parkes. His American editors wanted sex and rockets or gangsters in outer space, but Wyndham wanted to write something more substantial, something more intelligent, what he called “logical fantasy”. Then the Second World War began and everything changed.

He was forty-seven when he wrote his first important book The Day of the Triffids in 1951. He published under the name John Wyndham for the first time. He wanted the critics and public to think of him as a new writer not some hack writing for cash. The book was an immediate and major success.

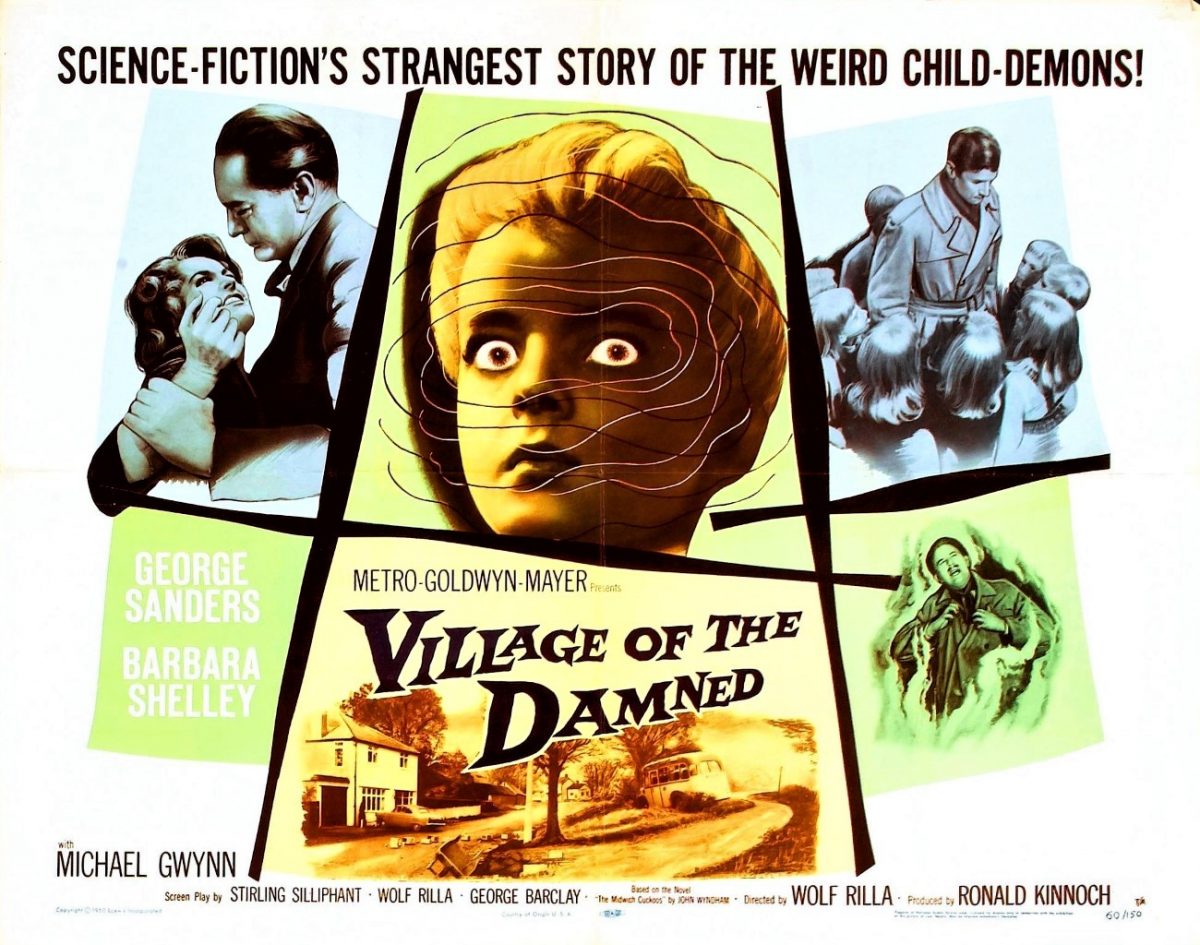

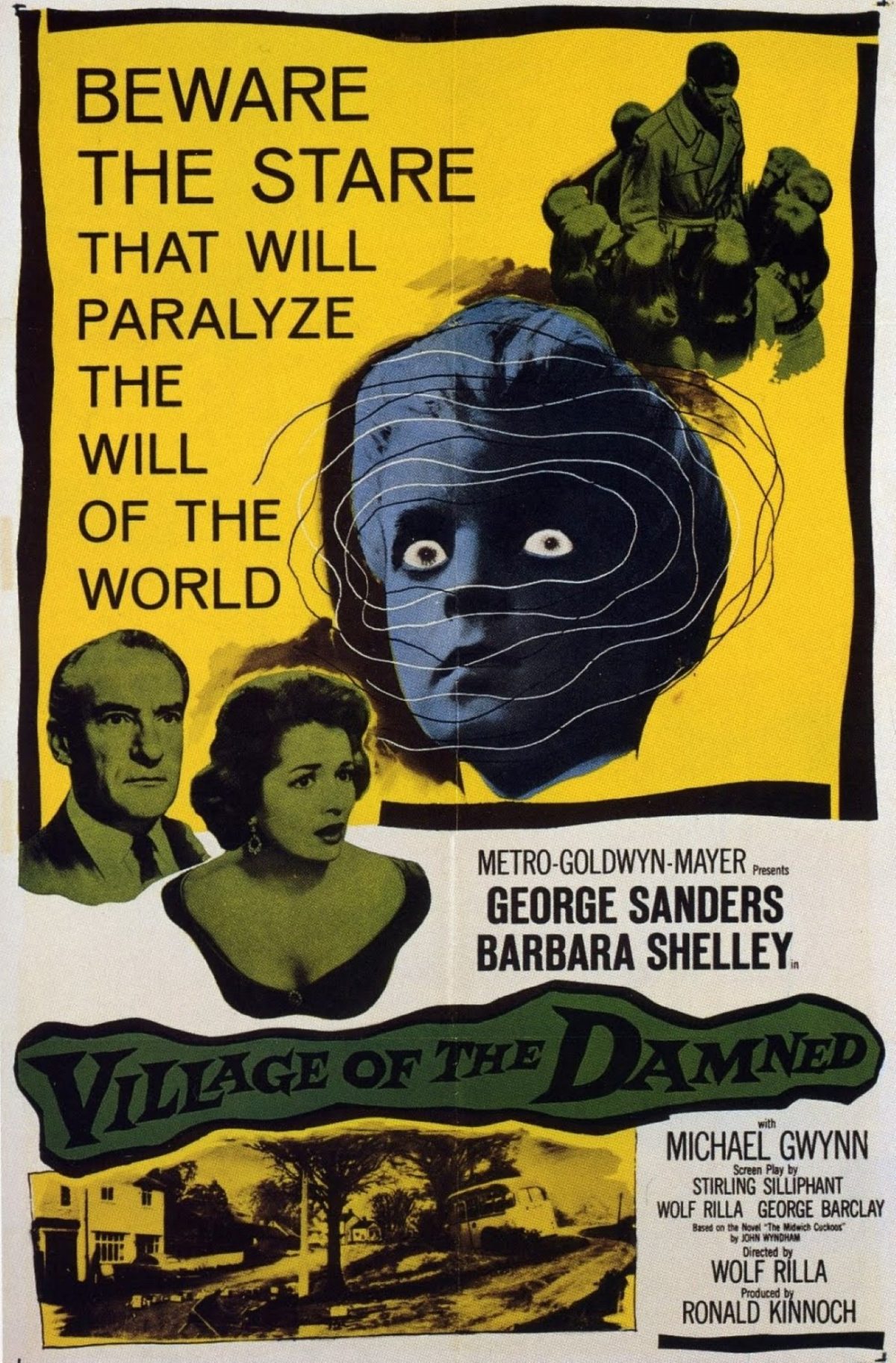

Wyndham followed this with The Kraken Wakes (1953), The Chrysalids (probably his best book) (1955), and then The Midwich Cuckoos in 1957. By then, Wyndham was so successful that this book was optioned for a movie before its release. The film was touted to star Russ Tambyn. But it came to nought. The producers then brought in established screenwriter Stirling Silliphant who relocated the book’s action from a sleepy English village to California. Ronald Coleman was cast to play the lead. However, details of the film were released which which incurred the wrath of the Catholic Legion of Decency who considered the book’s premise blasphemous.

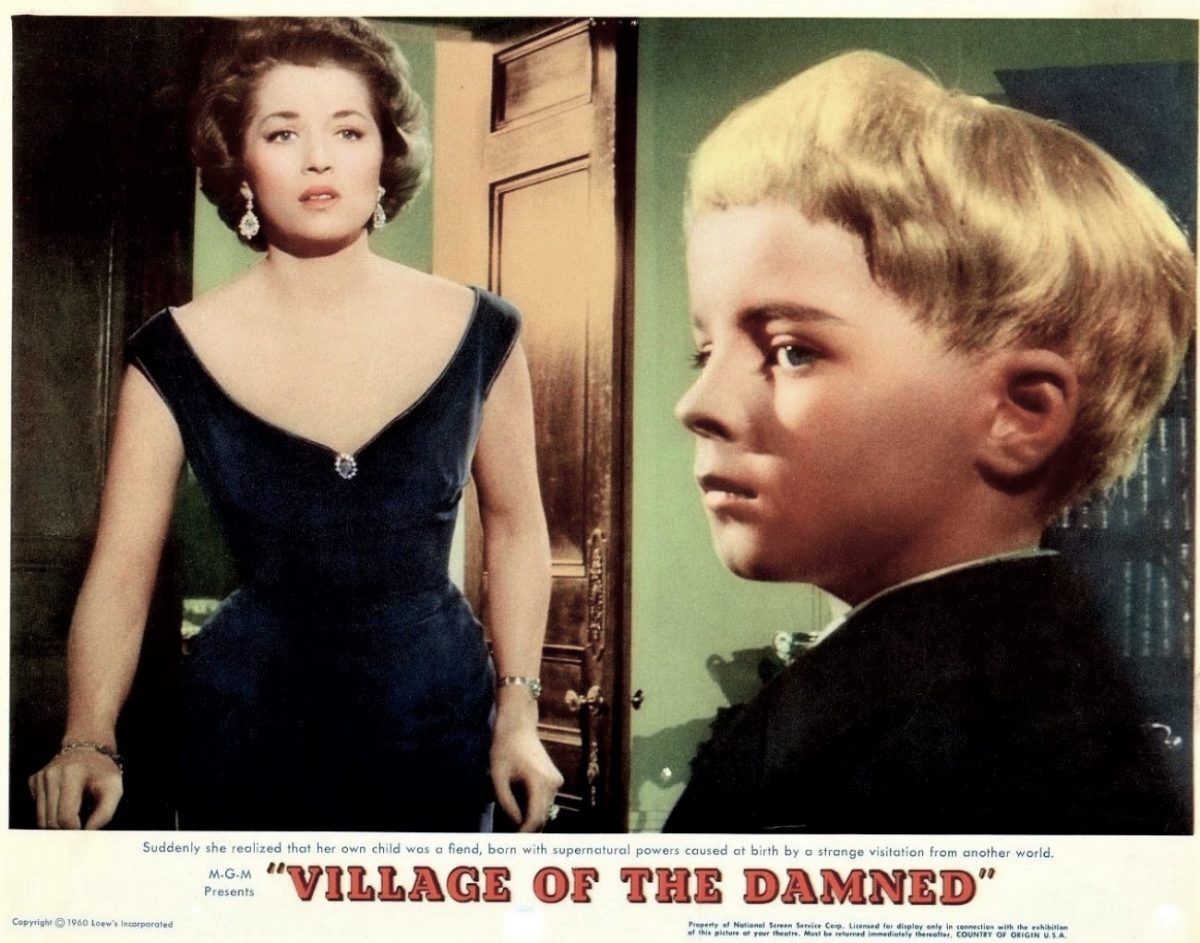

In The Midwich Cuckoos extra-terrestrials arrive on Earth to impregnate women of child-bearing age with their offspring. The Catholic Legion were outraged that Wyndham’s book made reference to “virgin births” and was ridiculing a central tenet of their faith. Surprisingly, no one was outraged that ET and his pals raped women. Or, that the story of their rape and the subsequent births of golden-haired, radiant-eyed telepaths was told by men rather than women. But it was a simpler time when self-awareness didn’t get in the way of a good story. As a sidebar: Wyndham had used the idea of an Earth woman being impregnated/raped by an alien in one of his earlier short pulp stories “Stowaway to Mars”.

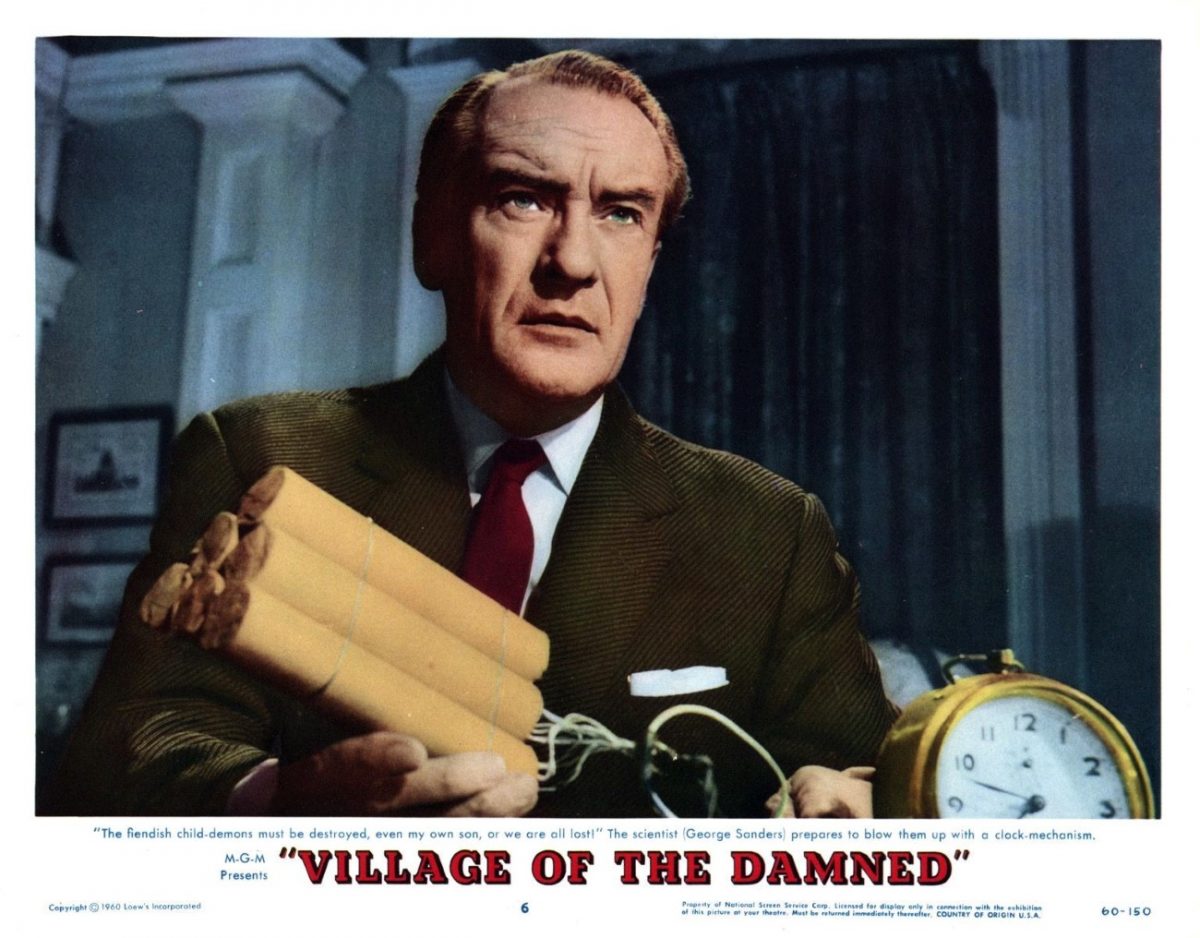

Back to the film: Coleman died and the producers decided to cut their losses and make the movie on the cheap. The story was relocated back to England, George Sanders (who coincidentally married Coleman’s widow Benita Hume) was cast in the lead. Wolf Rilla was hired to direct.

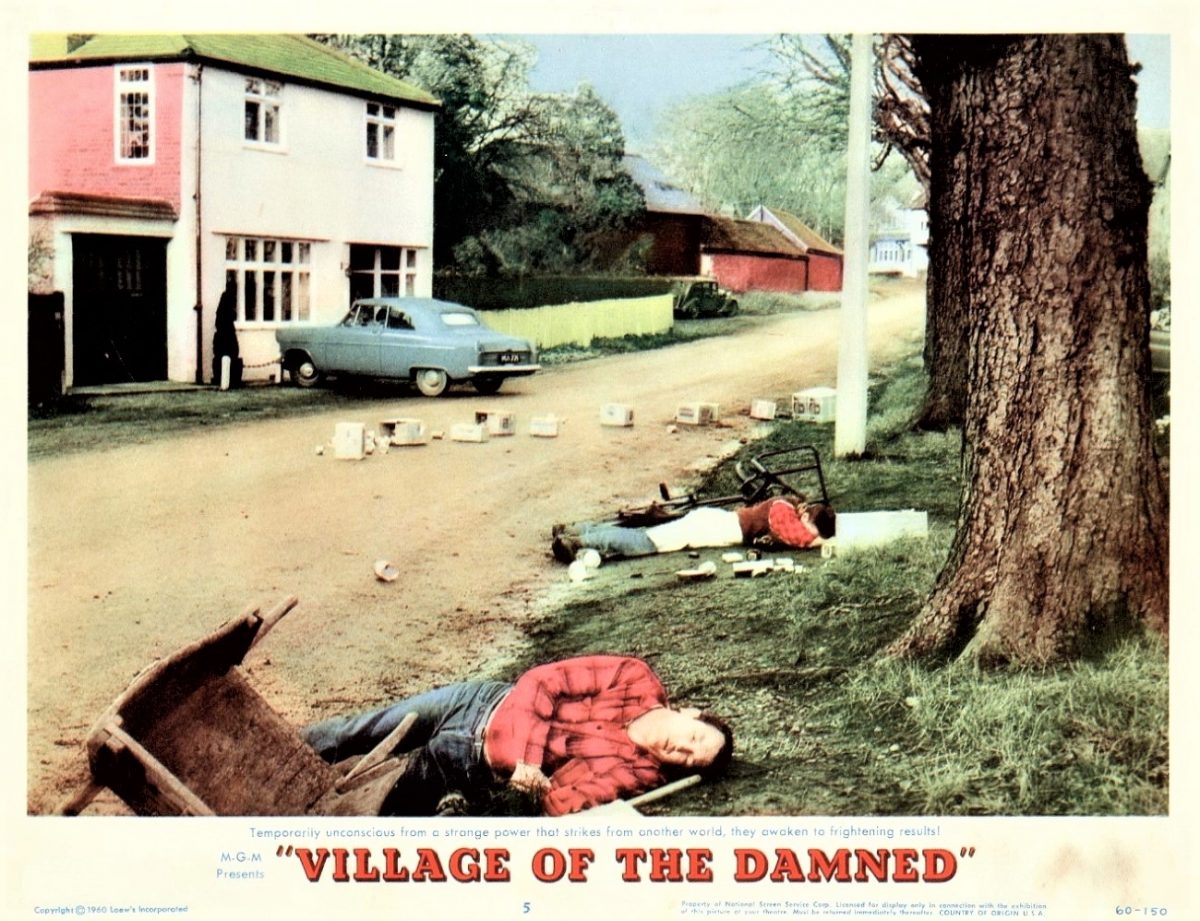

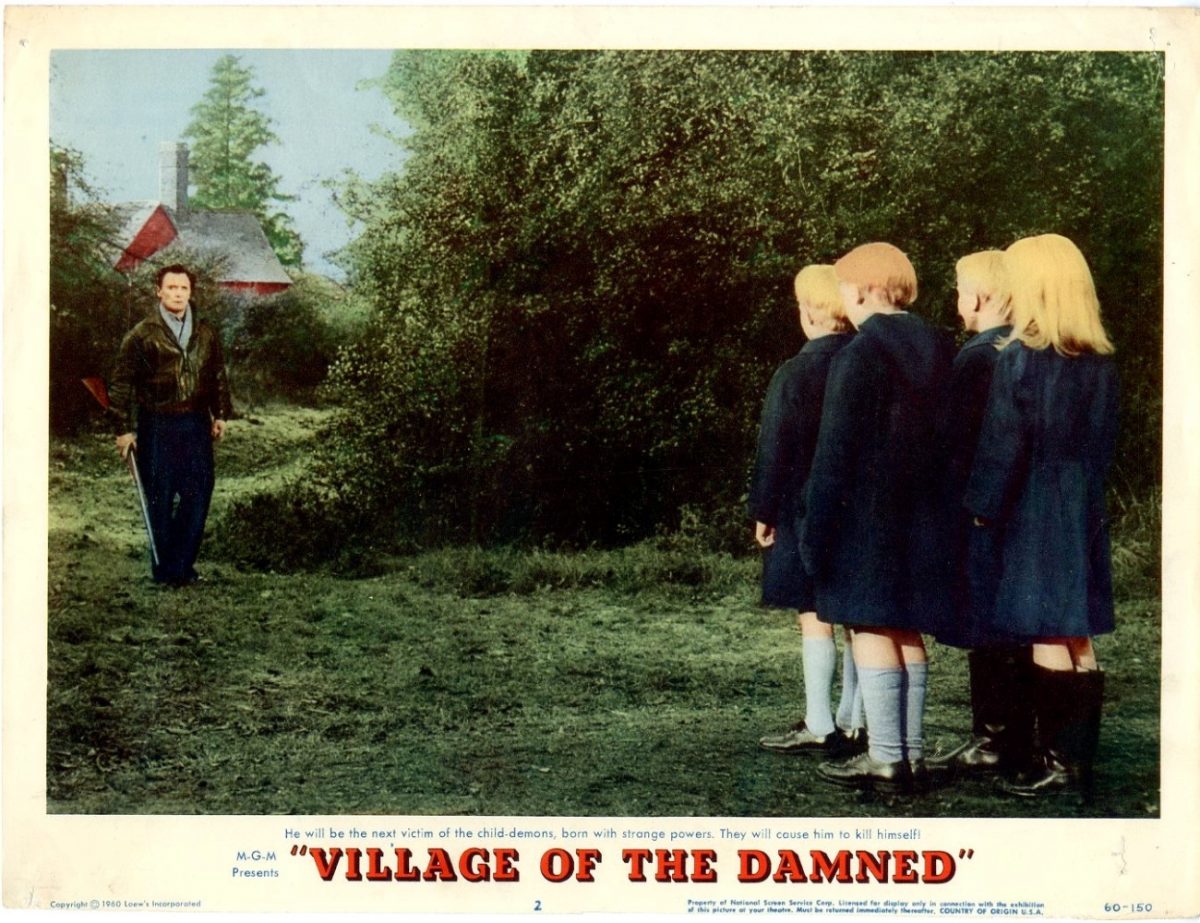

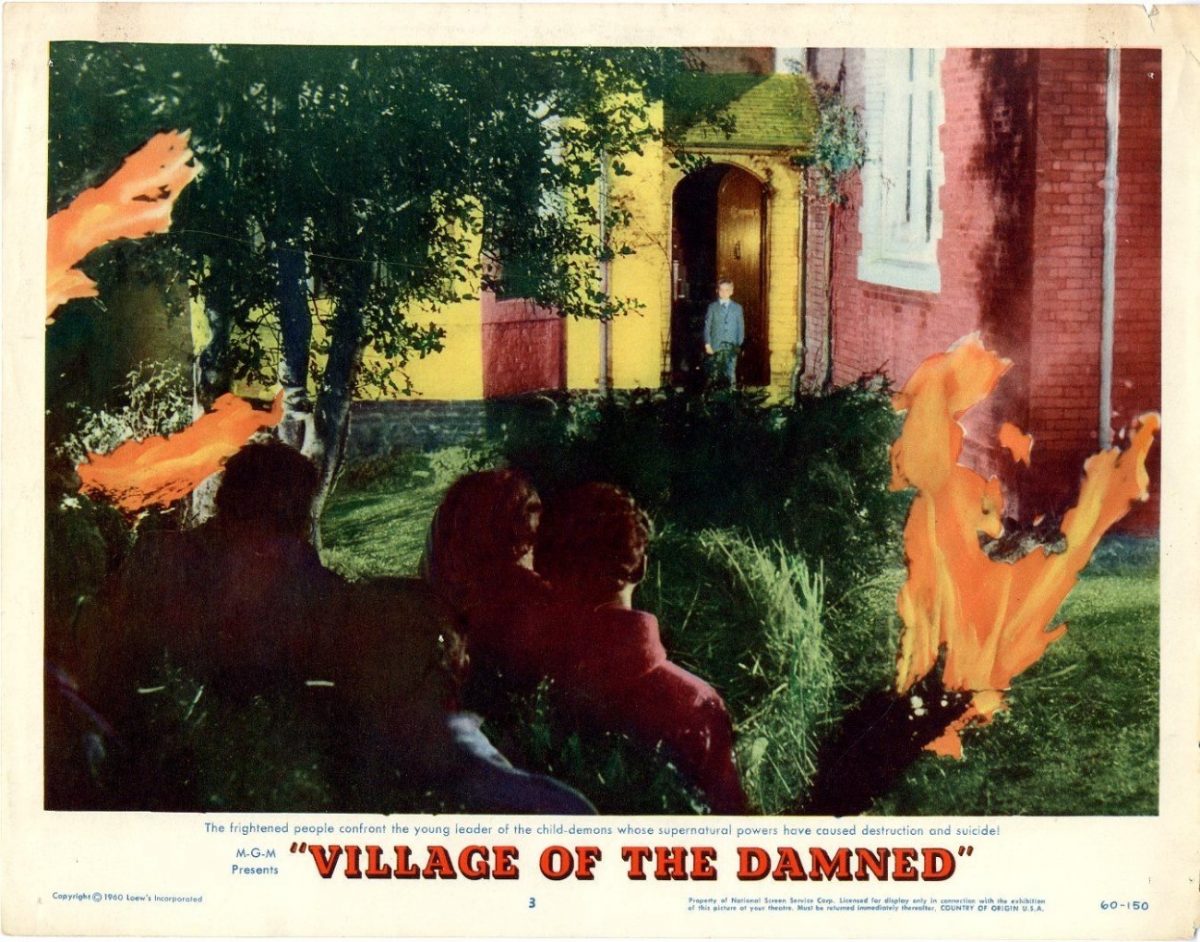

Rilla disliked Silliphant’s script. He began rewriting it. Though later said he felt disappointed there had not been enough time to make the changes he wanted. Small beer. For Rilla delivered a movie that is a classic. His technique to shoot the film like a documentary. He told the story simply rather than over dramatizing it–well, apart from the end and those moments when the alien children use their powers to inflict harm. As Rilla told the Guardian:

“What interested me was not to make a fantastic film but a film that was very real. To take an ordinary situation and inject extraordinary events into it.”

Far from being a “cosy catastrophe” the film, like Wyndham’s books, asks what it means to be human and to examine the lengths to which humans will go to protect their society.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.