“Trying to Define What May Be Indefinable”:

The Georgia Literature Commission, 1953-1973

It has been said that when the late Justice Potter Stewart penned his now-famous or (infamous?) definition of pornography, the “I-know-it-when-I-see-it” test in Jacobellis v Ohio, he was remembering his duty with the U.S. Navy during World War II. While stationed in Morocco, he knew all sorts of material exotic, erotic, pornographic, indecent, and lewd was available for price.

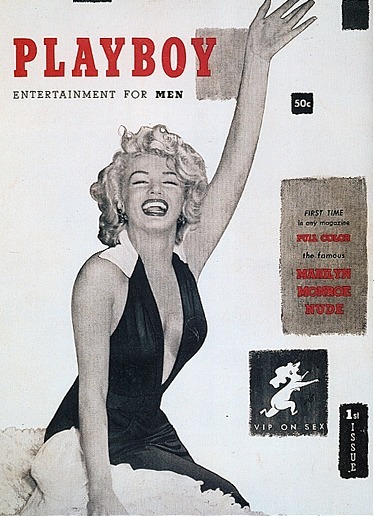

There can be no doubt that Georgia legislators who had served in the war remembered his type of material too. It was because of this memory coupled with the subsequent introduction of Playboy magazine in the United States and the culmination of the modern paperback book revolution in the years after the war that the Georgia General Assembly in February 9, 1953, created the state Literature Commission, the first such agency in the nation.

Dan Lacy of the American Book Publishers Council felt it was “an opportunity for real national leadership”. The public morality had to be protected. Obscenity had never been thought to be protected by the First Amendment. Not even the most liberal understanding of the role of expression in a libertarian society denied this.

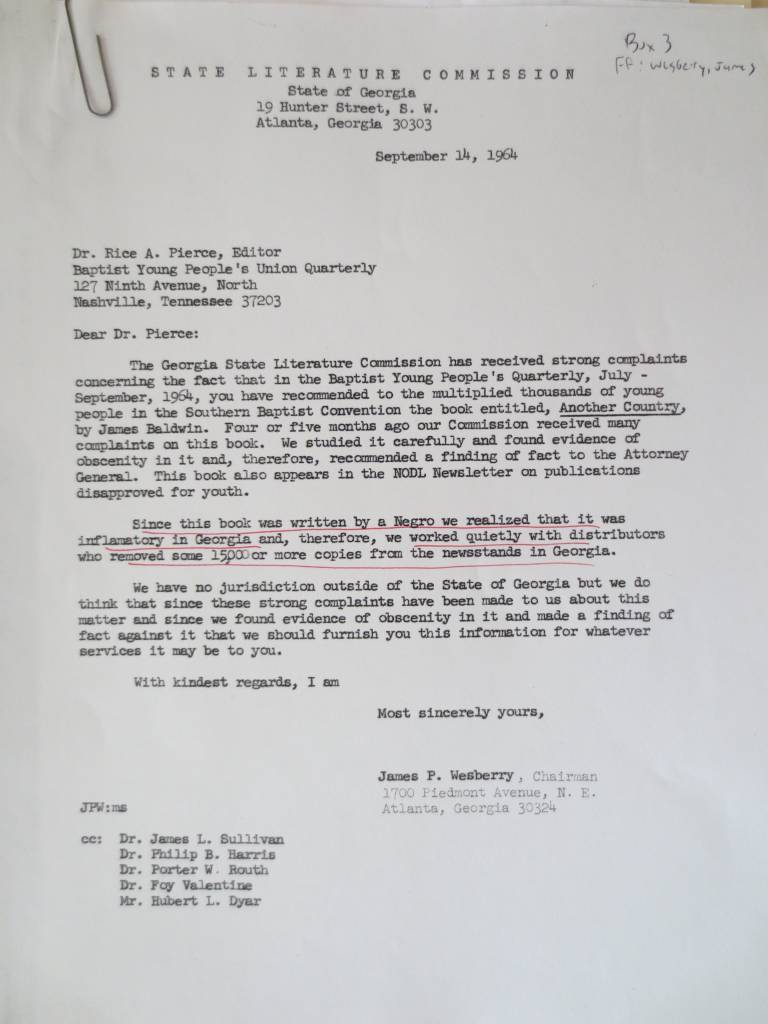

Yet the problem was one of definition. What legally was obscenity? That “obscenity is a purely subjective concept determined by the individual’s overt moral precepts and the generally accepted moral standards of society at a particular time” did not provide a satisfactory answer. According to the Georgia General Assembly, obscenity included any material “offensive to the chastity or modesty, expressing or presenting to the mind or view something that purity and decency forbids to be exposed”, a definition reminiscent of he one developed in 1908 by the Georgia Court of Appeals in Holcombe v. Georgi. Historically, obscenity laws nationwide tended to discriminate against what might be termed anti-social expression by minority groups and to support the status quo of the majority. This predisposition toward censorship was aggravated by several actors.

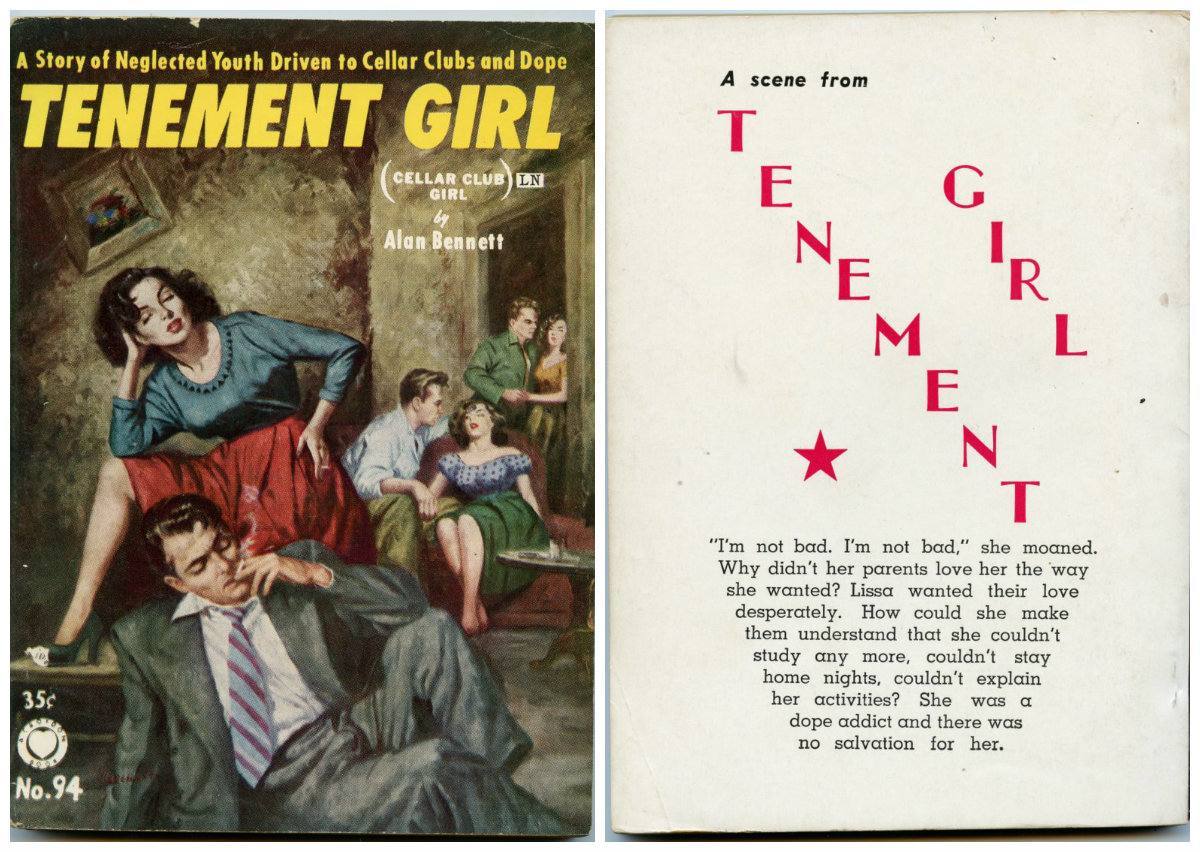

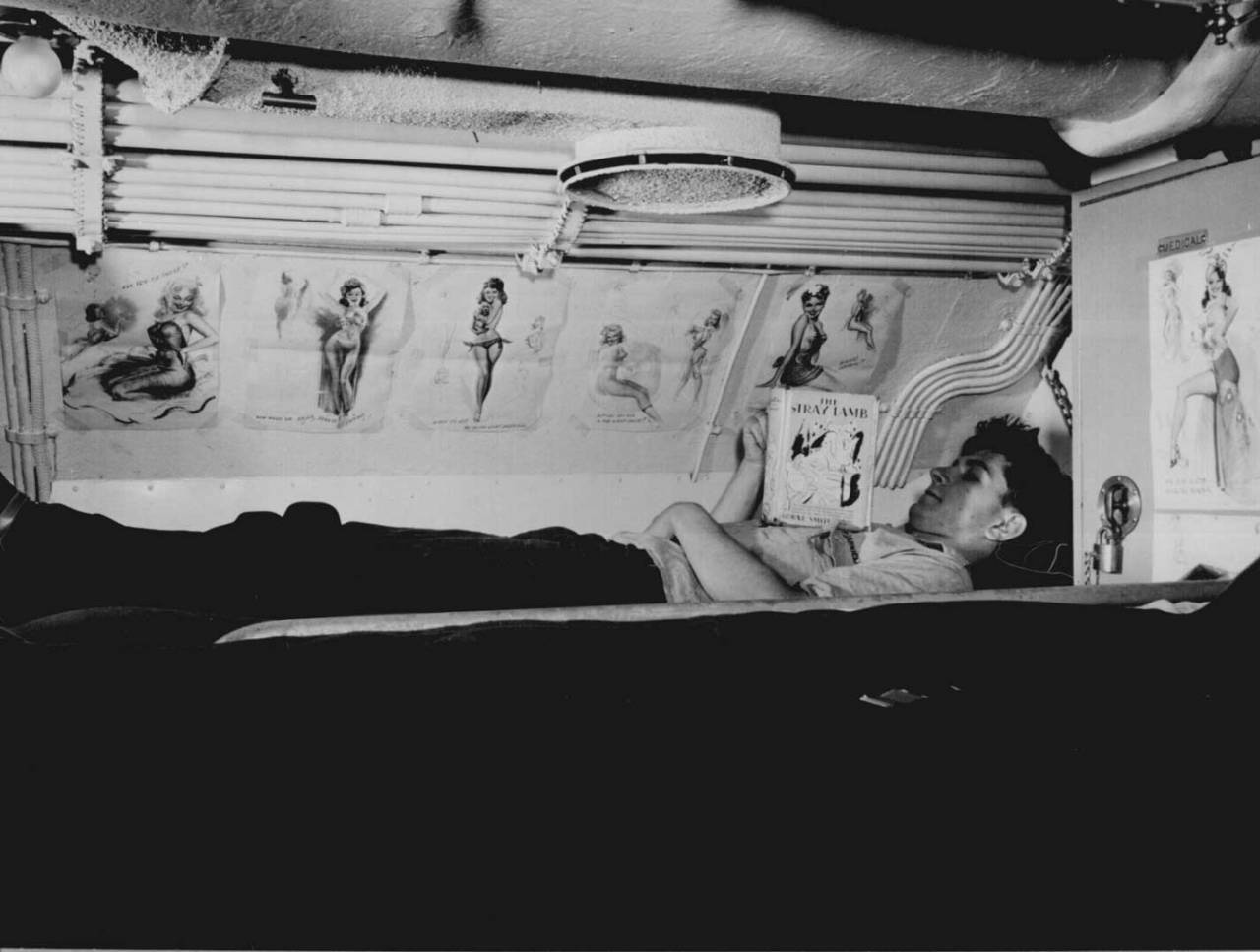

First, the modern paperback evolution, which began in 1939 and peaked in the 1950s, made books far more accessible than they had ever been before. Previously, only the upper social classes had been able to afford the classic works of literature. Paperbacks were the hope, the future of publishing. They enjoyed a surge of popularity during World War I, when GIs devoured these highly portable books as a means of passing time and escaping the drudgeries of war. Afterwards, readers were no longer limited to costly $2 hardback books found only in upscale bookstores; now they could obtain paperbacks in drug stores, bus stations, and elsewhere for 5 cents. The paperback book industry was only too anxious to meet this rising demand and subsequently attempted to glorify “all literature, even the lowest forms of escapism… in the name of morale.” The floodgates had been opened for he paperback industry, allowing even the least seemly of novels to flow through to the American public, which became “a plague of pornographic publications.”

American sailor reading in his bunk aboard USS Capelin, August 1943, United States National Archives

It was only after he GIs returned home that concerned citizens began to realize the extent to which the content of these “little books with lurid covers” had changed: “Wars in America have generally led to a relaxation of sexual censorship and the returning GIs of the 1940s craved stronger stuff than Betty Grable pinups. A new roughness was evident. With all the energy of an industry undergoing rapid development, the paperbacks – free of constraints that hampered movies and radio – resolutely pushed back the limits.” Alarmed by these changes, local groups began organizing for a new battle. The rise in numbers and strength of these groups, “generally community or religious organizations with some kind of national affiliation”, directly paralleled a rise in paperback publishing and distribution.

Girlie magazines, too, came under fire over concerns that were not entirely groundless. Many of these “cheesecake” magazines were quite debasing to women, and “sadism, masochism, fetishism, perversions, all were implicit in the prose and pictures.”

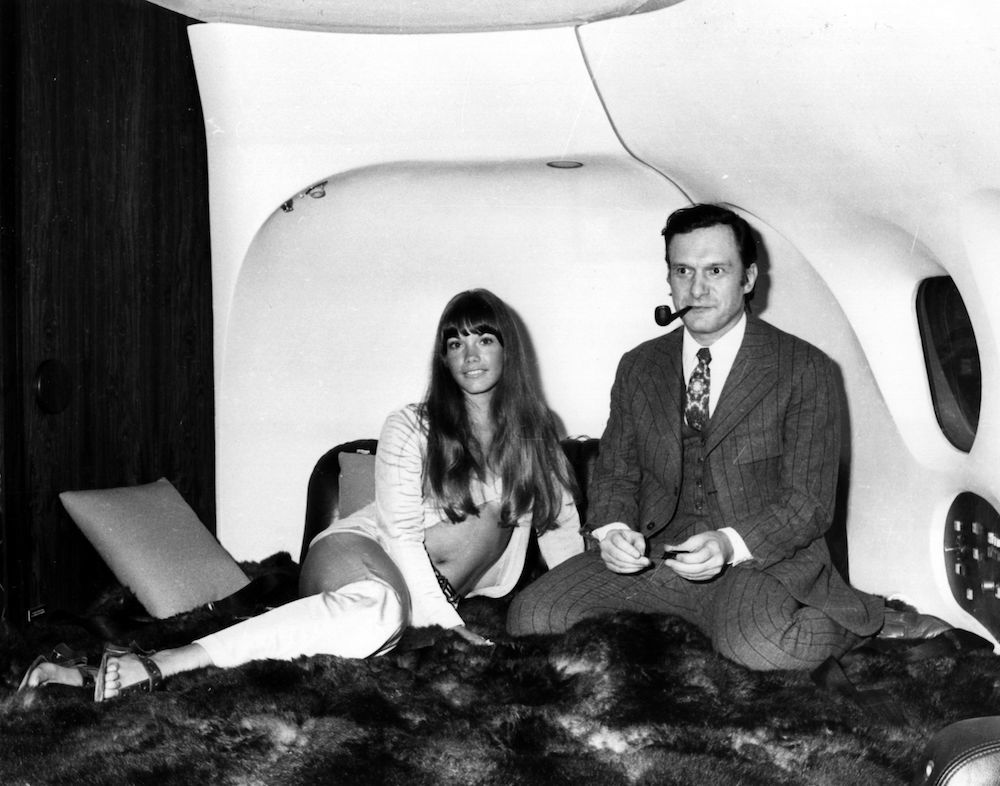

The emergence of such widely available, soft-core “girlie” publications – including Hugh Hefner’s Playboy, which featured “seminude… young, preferably innocent-looking girls, more fresh-faced than erotic or sophisticated [who] seemed on their way to cheerleading practice or to the sorority house” – caused an uproar in religious and civic circles, which stridently objected to the availability of such “trash” at public newsstands. Playboy was often singled out for criticism because of its broad-based popularity, and typical complaints in letters to newspaper editors argued that Hefner had “debased and prostituted sex and love and femininity to commercialize sex and sensualism.”

Finally, public uneasiness with the increasing boldness of paperbacks and magazines was heightened by concerns about growing juvenile delinquency among the nation’s youth. World War II had seen the necessary entrance of unprecedented numbers of women into the work force and had simultaneously created a generation of “latch key” children. Thus, many attributed the trend to parental neglect and “harmful” outside influences, such as pornography. The Atlanta Journal documented an “alarming increase in delinquency among young people” nationally and editorialized that “the majority of young delinquents come from homes where religion is neither taught nor practiced.”

Such pronouncements, not surprisingly, put a tremendous amount of pressure on citizens to demonstrate their commitment to a “morally decent” community and led to noisy admonitions of public officials for not pinpointing the “cause” of juvenile delinquency. As one observer of the time noted: “The search for elusive scapegoats (the parents, comic-book publishers, and others), upon whose shoulders the burden of social guilt can be transferred, detours many a well-meaning reform movement into a dead-end street.”

Increasingly, that scapegoat became “obscene” literature, and the pressure shifted to local city and state officials to do something about it. Like other legitimate areas of the postwar economy, soft-core pornography grew alongside the population and prosperity. Thus, the Georgia General Assembly unanimously voted to pass House Bill 247, establishing the Georgia Literature Commission to combat immorality as represented by “obscene literature.”

The commission- a “study agency [to investigate and recommend, with] no powers of censorship nor authority to punish offenders,” in the words of then-Governor Herman Talmadge

– was to consist of three members, citizens of “the highest moral character,” who would meet monthly to investigate “literature which they have reason to suspect is detrimental to the morals of the citizens” of Georgia. Literature was defined in the statute as “any book, pamphlet, paper, drawing, lithograph, engraving, photograph, or picture,” but specifically did “not include pictures used in projection of motion pictures or television.”11 The Bible, “weekly and daily newspapers, all Federal and State matters, and all reading matter used in the recognized religions and in scientific or educational institutions of the United States” were exempt, as were radio, television, and film.

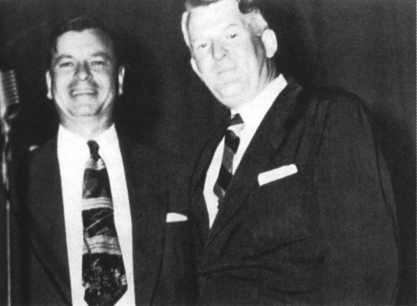

Talmadge asked James P. Wesberry, Sr., an Atlanta minister and occasional hunting companion, to head the commission. At first Wesberry declined because of his obligation to the thousand members of his congregation; he changed his mind when Talmadge reminded him of his obligation to the millions of Georgia citizens.

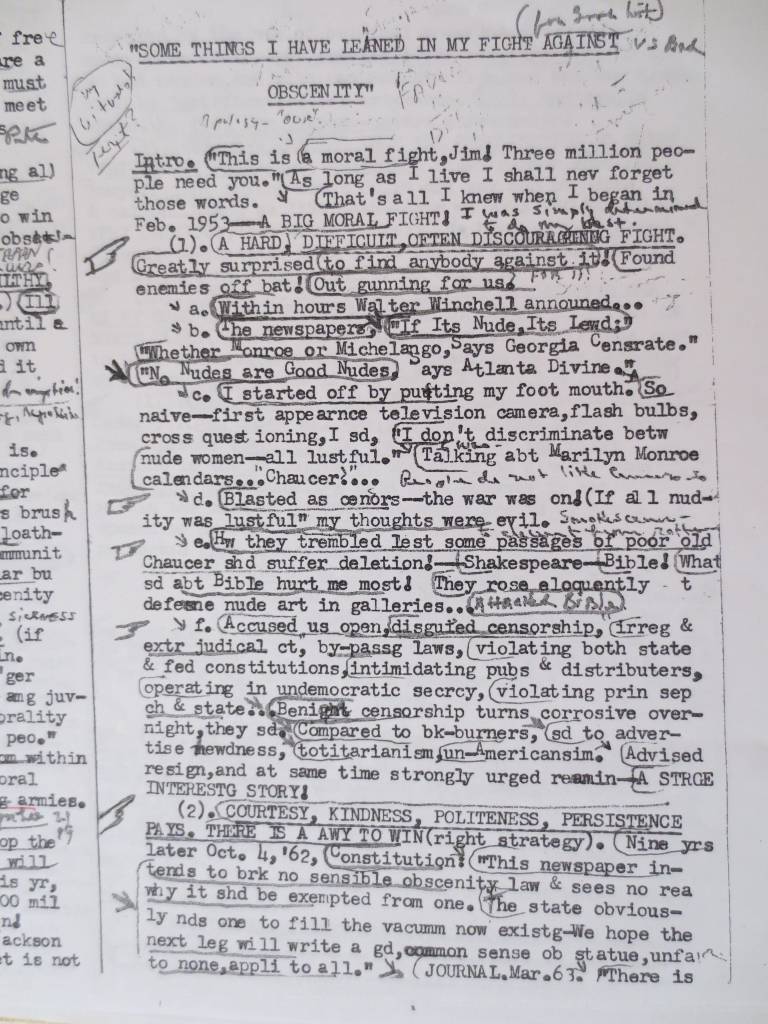

As chairman of the Literature Commission, Wesberry became the moral conscience of the state. As might be imagined, the commission found itself embroiled in a controversy over its purpose and identity from the beginning. First, there was Wesberry’s fear that the commission would be made to look like “a monkey to the nation.” Then, in response to a question about the potential offensiveness of certain works of art, “with more zeal for his task than common sense,” Wesberry answered, “I don’t discriminate between nude women, whether they are art or not. It’s all lustful to me.” Wesberry’s biographer characterized the statement as “the worst thing he could have said.” The comment was reported nationally. The media – from radio’s Walter Winchell to Collier’s magazine to the International News Service – “made great sport of [his] remarks and inferred that if all nudity was lustful to [him] that [his] thoughts must be evil.”

Finally, there were the serious, nagging questions. Wasn’t the commission really nothing more than a public censorship board? Wasn’t it engaged in nothing more than a witch hunt? Wasn’t it “an ‘irregular and extrajudicial court,’… by-passing existing laws,.. threatening freedom of the press,… advocating thought control,… intimidating publishers and distributors, [and] operating in undemocratic secrecy”?

The debate would continue for the next twenty years. Its first press release asserted: “The commission has no power to bar any publication nor does it have the power to censor, regardless of widespread reports to the contrary. The commission was established to aid the local [prosecuting attorneys] in the administering of laws of the state regarding obscene literature.” At the time the commissioners took office in 1953, Governor Talmadge was quoted as saying, “Censorship in a free country is repugnant to me and had the commission … any authority of censorship, I would have unhesitatingly vetoed it because such would be in contravention of our Constitution and our conception of free minds and free men.”

However, Georgia attorney general Eugene Cook told the commissioners: ‘You are a Censorship Board as far as determining whether literature is obscene under the definition of [state law] ;you are to that extent, but your censorship does not extend to the point of your being compelled to censor by public hearing. Your only power is to investigate, allow a hearing and… then turn over [your findings] to the prosecuting attorney.”

In an attempt to change public perceptions, the commission adopted a policy of reviewing and studying complaints from citizens of the state – who were expected to produce samples of objectionable material and be willing to testify against it – rather than initiating action on its own.

Then, if it determined something to be obscene, the commission could prohibit distribution by, first, notifying the distributor of its conclusions and, then, thirty days later recommending prosecution through the proper channels. However, it was just this ability to influence distribution that contributed to the perception of the commission as public censor. As a result, during the next three legislative sessions, attempts were made to reduce the commission’s powers to those of a gubernatorial advisory board. All were unsuccessful. The commission quickly discovered that Georgia’s statutory definition of obscenity was inadequate and, with the assistance of the state attorney general’s office, developed an eight-part test to aid in its deliberations:

1) What is the general and dominant theme?

2) What degree of sincerity of purpose is evident?

3) What is the literary or scientific worth?

4) What channels of distribution are employed?

5) What are contemporary attitudes of reasonable men toward

such matters?

6) What types of readers may reasonably be expected to peruse the

publication?

7) Is there evidence of pornographic intent?

8) What impression will be created in the mind of the reader, upon reading the work as a whole?

The commission’s intent was to apply this test “with particular force in regard to sexual matters,” yet not to consider “mere rudeness or uncouthness” a matter for its attention. Its efforts were not to condemn what might be termed the “erotic to the neurotic,” which did not otherwise offend “persons of balanced mentality.” The commission was “after sadistic literature that creates a sadistic appetite.”20 Interestingly, parts of the commission’s test appear in later U.S. Supreme Court landmark rulings on obscenity. Parts 6, 5, 1 and 8, and 7 seem to constitute the entire 1957 Roth test: “whether to the average person, applying contemporary community standards, the dominant theme of the material taken as a whole appeals to prurient interest.” Part 3 appears analogous to the third part of the 1973 Miller test: “whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.”

Most of the commission’s early work was performed through a program of mutual cooperation with publishers, distributors, and retailers, although the concept of “mutual cooperation” did not include full cooperation with the news media and the public. The commission felt that “nothing can be gained by giving … information [about books being removed voluntarily from retailers’ shelves] to the newspapers.” Attorney General Cook took an even more expansive position: He did not even believe the commission should hold open meetings. In his opinion, if distributors were given “an opportunity to be heard at a public hearing, then… they will get rich off the publicity.” The commission followed Cook’s counsel, which did nothing to promote a good working relationship between it and the news media. This prompted Commissioner Hubert Dyar, who was also the editor of the weekly newspaper, the Royston Record, to complain that

we have been handicapped in our investigation by a hostile attitude from some quarters who seem to fear that in trying to rid our state of [pornography], we will violate the First Amendment to the Constitution. Yet these same sources, who have tried to hamper the commission in every way, from ridicule to outright threats and requests for the members to resign, have made not one single constructive suggestion for curing this cancer of evil, which is being implanted in the minds of our youth.

With guarantees of press freedom, Wesberry contended, came responsibility.

The president of Playboy Enterperises, Hugh Hefner with girlfriend, Barbi Benton in his luxury DC-9 aircraft ‘The Big Bunny’ at Heathrow. The couple are en route to an extended holiday around Europe. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

As one of its very first acts, the commission asked for local distributors’ help in policing Georgia newsstands. This approach, which at first met with “enthusiastic approval,” stressed politeness without direct confrontation. Offensive material was voluntarily removed from sale as quickly as it was identified. This led to some interesting persuasive efforts on the part of publishers. The tone and intent of a letter to the commission from Hugh Hefner, publisher of Playboy, is typical:

Though we are producing a magazine aimed at an adult male audience, we are very conscious of our responsibility to the total society and most anxious to publish a periodical of quality and taste.

Unfortunately the waters have been muddied by a great many gross and tasteless “girlie” magazines that have attempted to copy some of Playboy’s features and as a result some have not been aware of the steady, continued development of our magazine. That you have been able to see the distinction between Playboy and these other periodicals is satisfying…and I felt it worth writing to you directly to tell you so.

As a result of such arrangements, the commission was able to operate for three and a half years “without a single recommendation of prosecution.”

In 1956, this “beautiful ideal of mutual cooperation” suddenly ended when Attorney General Cook, in response to a query by magazine distributors, ruled that a finding of obscenity by the commission was “a finding against the particular issue of the publication under review [and not] a determination with respect to the title… and all subsequent issues thereof.” Thus, the commission was required to recommend prosecution of all material it determined to be obscene. The commission, he wrote, only had the authority “to make findings on literature ‘in being’ at the time.” [Its actions] “could not apply to any future issues of [a] magazine for the reason that there would be no basis for determining the possible content of any such future issues.”

As a result, the commission felt that its policy of mutual cooperation was no longer workable. Although, in the words of Chairman James Wesberry, it had been “literally leaning over backwards to cooperate with distributors,” the commission had just had its workload dramatically increased. A single finding of obscenity would no longer keep a periodical from being sold; a new finding would be required month after month after month. Otherwise, its efforts would be for nothing. The commission felt it had “no alternative:” “We [have been] forced to either do nothing or to recommend prosecution on individual issues” of magazines.

This decision brought expressions of dismay and outrage from magazine distributors. Harry Elson of the Atlanta News Agency complained that “he was at the point where he did not know whether he was cooperating or not. In the past he had cooperated in every way, but he did not know which magazines to put out and which not to put out. He stated that there was supposed to be some freedom of the press, [but] that the state of Georgia had a law and he did not know how to interpret it. He had been cooperating fully and now he found himself eligible for prosecution.”

As a direct consequence, the commission was sued in federal district court by four out-of-state publishing companies, who charged that the statute establishing the commission – and particularly the legal definition of obscenity therein – was unconstitutionally vague. On January 4, 1957, a special three judge appellate panel ruled that the statute as “correctly construed” did not raise a constitutional question. Because the court concluded that the commission did not have any direct powers of censorship or prosecution – it could only investigate and recommend that a publication not be sold or that a distributor be prosecuted – the suit was subsequently dismissed.

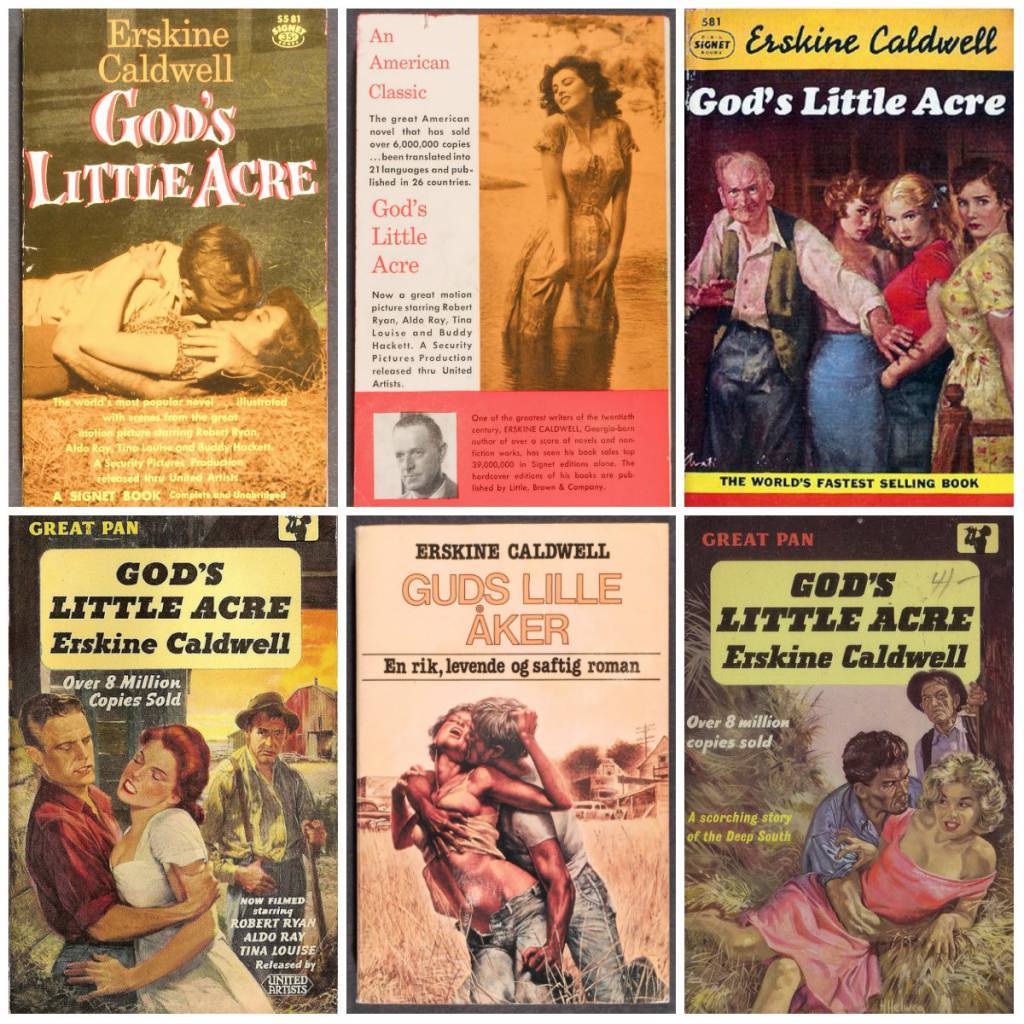

A revised policy statement from the commission was mailed to distributors and retailers: “The alleged removal of any material from sale is done voluntarily by the individual distributor or retailer. The commission… cannot advise the removal of any material, nor can the commission remove any distributor or retailer from the threat of prosecution on any past, present, or future materials.” Its first recommendations for prosecution soon followed. The commission’s first ruling with respect to a novel involved a paperback edition of Erskine Caldwell’s God’s Little Acre

In 1958, the legislature – “without any discussion to speak of” – enacted Senate Bill 207, amending the enabling statute to reflect the U.S. Supreme Court’s test of obscenity set forth in Roth v. United States/Alberts v. California and to streamline the commission’s procedures of operation, while making it more powerful. First, the definition of literature was expanded to include the word “periodical.” But more importantly, obscenity was redefined as “any literature which if, considered as a whole, its predominant appeal is prurient interests, i.e., a shameful or morbid interest in nudity, sex, or excretion, and if it goes substantially beyond customary limits of candor in description or representation of such matters.”

In addition, while not limiting the power of the state’s prosecuting attorneys, the commission was given the authority to issue subpoenas to require testimony at its hearings, to cite for contempt those who failed to respond, to seek a court injunction to stop material from being sold, and to remove it from newsstands. This change provided the commission with a quick method of controlling literature, provided an injunction was granted. However, a final determination or judgment of obscenity was still the responsibility of the courts. The commission was also authorized to appoint a fulltime executive secretary to supervise its activities.

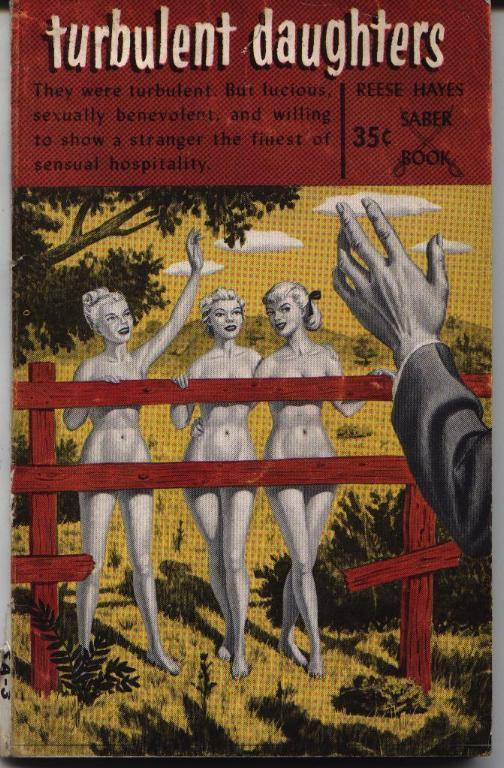

Commissioner Hubert Dyar was chosen to fill this position on April 7, 1958. In July, using its new injunctive powers for the first time, the commission stopped distribution by the Plaza News Company of Reese Hayes’s book, Turbulent Daughters. A few months later, another injunction stopped the same distributor from selling Betty Short’s book, Rambling Maids. As a result, “the commission’s influence began to be felt even [more] strongfly.”

By April 1960, distributors had agreed to pull more than 119 publications from sale to avoid such actions. The commission’s effort suffered a serious setback in 1962 when the Georgia Supreme Court threw out the state’s obscenity law as discriminatory because certain media were exempted from its review. Calling the law “the rankest form of discrimination,” Chief Justice W. H. Duckworth wrote, “No rational distinction can be found between the evils which the act seeks to prevent … by those to whom the law is applicable or those whom the law exempts from its operation.” The decision “left the [commission] virtually stripped of any power.”

At the commission’s urging, the General Assembly enacted a revised statute during the 1963 legislative session, correcting and expanding the scope of the commission’s review powers but with provisions otherwise essentially the same as the first. Yet even this corrective effort generated disagreement from those who felt that because of definitional difficulties it was “not necessary to define the meaning of obscenity… and the test for obscenity perhaps could be handled better if left to the courts to administer.”

In 1964, the Georgia legislature adopted House Bill 131, which strengthened the commission yet again, giving it the power to proceed directly against questionable material – instead of against its author, publisher, or distributor – through declaratory judgments, the ability to request any Georgia superior court judge to declare material to be obscene. Declaratory judgments were an additional weapon in the commission’s arsenal against pornography in that they were applicable statewide, although it was still up to individual prosecuting attorneys to determine whether criminal charges would be brought against persons distributing such material. The vote in the Georgia House of Representatives was unanimous. The Senate vote was not because Senator John Gayner of Brunswick strongly opposed the changes, declaring that the activity of the commission “strikes at the core of one of the fundamental freedoms of this nation.”

That same year – with the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Jacobellis v. Ohio, which applied a “national” community standard to issues of obscenity – pornography essentially became a federal question, rather than a state one. With increasing frequency, the Supreme Court – sometimes called the “High Court of Obscenity”during that period – accepted the task of deciding several cases involving challenges to Georgia’s obscenity laws and overturning them. However, subsequent rulings after 1957 found no basis for

obscenity.

That the commission was aware of the change in standards heralded by the new decade is evident in Hubert Dyar’s statement to his fellow commissioners: “We could not get an indictment… on a nude magazine, unless the pubic hair is showing.” In part, Wesberry felt that this was the result of timidity on the part of prosecuting attorneys: Distributors, he explained, are “reputable persons, have fine families and many friends.”

Yet there was also a growing feeling among some legislators that the commission threatened liberties guaranteed by the Bill of Rights to the U.S. Constitution, despite the commission’s assurances that works “with any iota of redeeming literary importance” were safe. In 1965, Senator Gayner – having failed the previous year to stop the legislature from expanding the commission’s powers -tried again. First, he proposed deleting the commission’s funds from the state budget, fearing that “the commission with the state’s millions of dollars behind it ‘can control what people read.'” Second, he proposed stripping the commission of its injunctive powers, granted in 1958. Finally, he proposed abolishing the commission outright. The effort eventually failed “because many senators [were] afraid a vote against [it] would be misunderstood.”

However, it did signal for the first time the General Assembly’s willingness to question the value and effectiveness of the commission’s efforts. Through 1967, the commission took legal action in only six instances, most of them in jurisdictions outside metropolitan Atlanta where there was “a better chance of success.” The first involved George Smith’s Strip Artist, which had been sold in Savannah.

However, it was the legal battle in the last of these cases “against a carefully chosen publication” that signalled the beginning of the end of the commission’s activities. Wesberry remembered: “We needed a test case and were looking for a book that we considered to be the most obscene we could find, completely devoid of social values and so far beyond the good taste and common decency that everyone would agree with our ban.”

On August 19, 1966, the commission sought and received a declaratory judgment in Muscogee County Superior Court in Columbus that Alan Marshall’s 5m Whisper- described as “awful” by Wesberry – was obscene.41 A unanimous Georgia Supreme Court also sided with the commission, concluding that “in our view, the book is filthy and disgusting. Further description is not necessary, and we do not wish to sully the pages of the reported opinions of this court with it.” The U.S. Supreme Court, however, reversed the judgment without opinion in a memorandum decision – without any explanation as to why the book was not obscene, without any comment about the standards applied by Georgia courts determining it to be obscene, and without any ruling on the constitutionality of the commission itself or on the appropriateness of its procedures.

In other words, the Georgia Literature Commission, which appeared to be constitutionally formed because of the Court’s silence, engaged in official actions that somehow were a violation of constitutional guarantees. “We were stunned,” Wesberry later said. The result was that, in the arena of obscenity law in Georgia, the Court only “compound [ed] confusion,” to borrow a phrase from Justice John Harlan.

The overall effect of the ruling on the commission’s activities was pronounced. Its efforts “slowed considerably.” At the height of its power in 1964, Atlanta was “the worse [sic] cesspool in the country” and the commission reviewed 427 complaints. The following year, commission members were complaining about “the stupendous weight of the problem of obscenity in our state.” By the end of 1967, Atlanta had “become the capítol [sic] of pornography,” yet the commission considered only 22 complaints. Most of its efforts now were focused on promoting good reading habits among the state’s youth through a partnership with wholesale book distributors and the Youth Council for Good Reading. By 1969, the commission’s reduced caseload was reflected in an annual budget the legislature had refused to increase. Because the commission had more than $1,000 in funds remaining from the previous year, the General Assembly rejected its request for $23,000 and approved only $20,000 for operating expenses.

Then, in 1971, after years of steady support, its annual appropriation was reduced by almost 20 percent. Ironically, then-Governor Jimmy Carter’s decision to cut the commission’s budget coincided with his public pronouncements decrying pornography. He proclaimed May 9-15, 1971, “Fight Pornography Week,” and declared his intentions “to do everything I possibly can to rid Georgia of pornographic literature and movies,” urging “all Georgians to join … in this fight.”

However, the Georgia Literature Commission did not benefit from Carter’s commitment. As part of his election pledge to reorganize and reduce state bureaucracy, the Carter administration instituted a zero-based budgeting system, which required state agencies to justify their existence each fiscal year. The commission, then, was forced into the position of having to defend its legitimacy, deserving of government funding. Unfortunately, however, in order to prove that the agency was still needed, commission members were forced to acknowledge that past efforts had been largely ineffective. “When measured literally by the number of criminal prosecutions initiated by our agency, the accomplishments may seem small,” Wesberry wrote. Thus, the commission’s prospective activity summary for fiscal year 1973 focused on the future: “Due to recent court decisions, the Commission expects to see much more success than has been accomplished to the present time.” An increasing sense of urgency could be felt among members, and Hubert Dyar voiced this growing concern in a letter to Senator Eugene Holley, requesting the status of the commission in the administration’s “reorganization plan,” and questioning “how we are provided for in the budget.”

Clearly, the commission could no longer afford to assume it would receive funding as a matter of course. By June 1972, hints of the Carter administration’s dissatisfaction

with the effectiveness of the commission were evident. Plans were being developed to move the commission to smaller offices, and an attempt was made to dispose of it by shuffling responsibilities. Calvin Cruse, the administration’s budget analyst, requesting the commission’s latest activity report and funding needs for fiscal year 1974, suggested “that the Governor consider assigning this agency to another State Department (preferably the Law Department) for administrative purposes.”47 When efforts failed to transfer the commission’s duties to the attorney general’s office, Carter tried another tactic. In September, he implemented a plan that would solidify his

stance as “tough on pornography,” yet circumvent the need to shut down the commission. Carter chose to argue that while certainly “not their fault,” the commission had become no more than a “mere complaint department” and was “completely ineffective in stopping the spread of obscenity,” the result of recent Court decisions that had “placed enforcement responsibility on the local level and left the state Literature Commission without enforcement power.” He then named a new six-member advisory committee on pornography with instructions to”make a crash study of the pornographic situation in Georgia” and report back to him with “recommendations for fresh legal action.” The committee recommended the creation of a new literature commission with a special, “circuit-riding prosecutor on its staff’; nothing, however,

finally came of this proposal.

Carter’s last, most subtle tactic to ensure the demise of the commission was to take no action at all. Both he and the next Georgia governor, George Busbee, “declined” to appoint replacements for Commissioner William Pirkle who died on October 11, 1972, and Hubert Dyar, executive secretary, who died on October 4, 1973, at age forty-seven, the result of complications following surgery. Thereafter, the three-member agency was precluded from conducting official business as it was never able to have a quorum. It was, thus, “impotent” and, as a consequence, legally “inactive.” Though Wesberry never said so publicly, he held Carter responsible: “Some of the best people I know couldn’t see what was wrong. It broke my heart, [for] when you’re fighting obscenity, you’re fighting the devil.”

From 1973 on, the commission’s activities can only be described as its few last gasps for life. Wesberry was then the only living commission member, and despite his efforts, his appointment – which officially ended on April 1, 1973 – was never renewed. The last expenses deposit for the commission was made in June 1973, and the last minutes from a “meeting” were recorded October 9, 1973, during which Wesberry elected himself interim executive director and telephoned the governor’s office to request that Carter appoint two new members. The commission’s last financial statement on file is for the quarter ending December 31, 1973.

Finally, in January 1974, the Office of Budget and Planning rejected the commission’s quarterly allotment request because i had not been signed by its legally elected executive secretary, Hubert Dyar, who had died the previous year. The Georgia Literature Commission was completely paralyzed. This fact is reinforced by the words written in bold on the outside of Governor George Busbee’s file on it: “Not Going To Appoint.”51 Wesberry also retired as minister of the Morningside Baptist Church the following year to become director of the Lord’s Day Alliance, an interdenominational group whose aim is to promote “the Lord’s Day as a day of worship, rest, family culture, and Christian service.”

Although the 1953 statute creating the commission was never officially rescinded by the General Assembly (for what Georgia legislator would want to be seen voting for pornography?) , the new Georgia Constitution of 1976 authorized eight constitutional boards and commissions. The Literature Commission was not among them.

Had the state been committed to the commission’s efforts, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Miller v. California return to state standards of obscenity would have been welcome news. However, afterwards, Georgia continued to have problems applying the Court’s definitional guidelines, for in Jenkins v. Georgia the Court ordered a re-evaluation of state obscenity laws in light of the new Miller standards.

The problem has been, is, and probably will always be that the courts have recognized that the distinction between what is and what is not obscene is a “dim and uncertain line” requiring “sensitive [definitional] tools.” Standards are shifting and indeterminate, which makes the commission’s overall effectiveness difficult to assess. Testifying before the state Senate Judiciary Committee in 1965, Commissioner Hubert Dyar reported that whenever the commission got an injunction against the sale of a book, sales in

other locations increased significantly. Wayne Kelley concludes that during much of its existence, the commission was “notoriously impotent.” Grier Stephenson is of the opinion that the commission’s effectiveness was greatest, and most dangerous, in the “extra-legal” arena, “when distributors began exercising selection on their own, in hopes of pleasing and appeasing the commissioners.”That same approach, however, is described by James Kilpatrick as “a record of discreet and effective action over a period of years.”

Thus, the fight may never be winnable because while courts have been willing to rule that single issues of specific periodicals violate obscenity laws, they are only willing to do so on an issue-by-issue basis.The commission either couldn’t get a particular book or periodical to examine, or by the time commissioners read it and were ready to take action, the book was sold out and the damage done, or the next issue of the magazine was ready for distribution.

Also, technological developments in the publishing industry quickly outpaced the commission’s ability to monitor abuse. State Representative William T. Bodenhamer of Tift County, one of the original sponsors of the bill creating the commission, understood the problem early on. As society and technology developed, legal remedies would become increasingly ineffective in the fight against pornography:

“Something is happening to our culture . . . whether we admit it or not… You will have to depend upon something that goes beyond the law. [You will have to] depend

upon the people” themselves. Yet this very failure of law as a social institution to regulate and protect concerned Hubert Dyar, himself a journalist:

I have become alarmed to the possible loss of “freedom of the press” rights if obscene publications are allowed to continue to be circulated. An official organization to curb this circulation to me is a protection of this freedom which is being abused. If we continue to do nothing concerning this problem, the people will rise up in indignation and without proper leadership demand violent actions which could affect not only the obscene and pornographic material, but the good and worthwhile publications as well.

Three options, then, appear possible. First, society agrees it cannot define obscenity and assumes that all such expression is protected by the First Amendment, a position that neither Dyar nor Bodenhamer advocated. Second, society accepts many disparate standards of obscenity and allows the individual’s ethical principles to define and enforce what is acceptable for himself or herself. Or, third, society defines obscenity to protect and focus the public discourse vital to self-government. The challenge is to choose which option, despite potential difficulties, offers the most promise.

- Courtesy of the Georgia Historical Quarterly.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.