On the corner of two tight residential streets, next to Dollis Hill underground station, stands an unobtrusive block of modern flats, set just off the road. At first glance there is nothing to distinguish it from dozens of other housing developments that have sprung up in this part of north-west London, but a closer examination reveals a plaque on one of the exterior walls remembering Jayaben Desai, and a new street sign: Grunwick Close.

Forty years ago, the Grunwick Film Processing Laboratory stood on this site, and when workers walked out on 23 August 1976, it was about to become one of the most famous landmarks in Britain. Soon the adjoining roads would be crammed with thousands of pickets, and in an era of strikes involving gigantic car plants and hundreds of coal mines, it was the unlikely setting for an industrial dispute dubbed ‘the Ascot of the left’. To commemorate its fortieth anniversary, a local exhibition offers a fascinating history of the extraordinary events that unfolded.

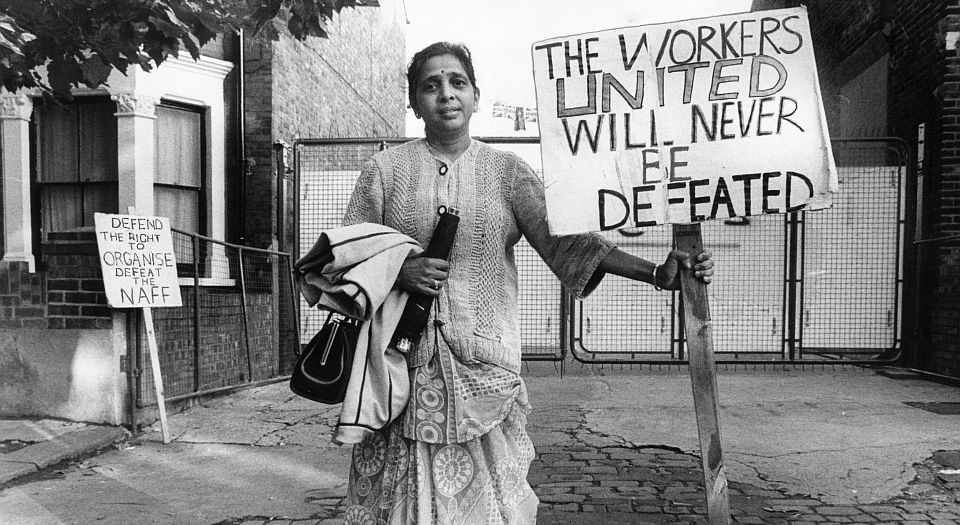

Accounts of the dispute’s origins vary slightly, but the gist of it is as follows. Devshi Bhudia was dismissed on Friday 20 August, apparently for working too slowly. Three others – Chandrakant Patel, Bharat Patel and Suresh Ruparelia – walked out in support of him. That evening Jayaben Desai was about to leave but was ordered to do overtime without prior notice – something workers at the plant were expected to do as a matter of course. She refused, and walked out along with her son Sunhil. It was the last straw for many at the plant, who had put up with low pay and working conditions that, as Desai put it, ‘nagged away like a sore on their necks’.

‘A person like me, I am never scared of anybody’, she told her bosses before leaving. Her line manager, Malcolm Alden, is said to have then likened her and her co-workers to ‘chattering monkeys’, whereupon she famously retorted: ‘What you are running here is not a factory, it is a zoo. But in a zoo there are many types of animals. Some are monkeys who dance on your fingertips, others are lions who can bite your head off. We are the lions, mister manager.’

Cross-examined later by Lord Scarman, Alden was at a loss to explain why the workers (described by Grunwick boss George Ward as ‘my ladies’) had walked out. He recalled how, ‘All of a sudden, she [Desai] kind of exploded and said, “I want my freedom”… [that] is the phrase that stands out in my mind.’

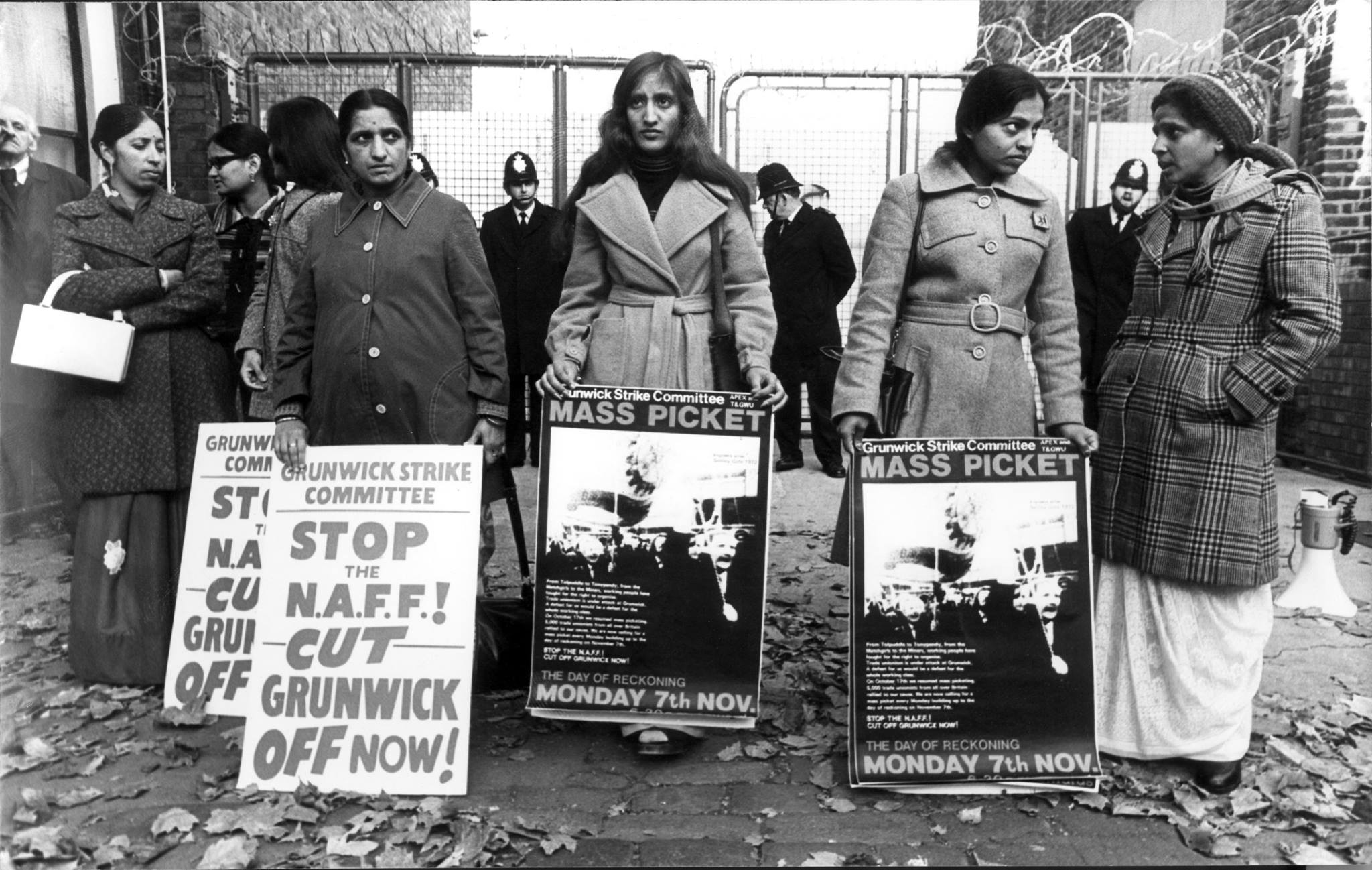

The upshot was that more walked out of the Dollis Hill site the following Monday, joining a number of others to become the so-called ‘strikers in saris’. The local Citizens Advice Bureau gave the strikers the numbers of Brent Trades Council and the Trades Union Congress (TUC), who advised them to join the Association of Professional, Executive, Clerical and Computer Staff (Apex). Local workers soon got to hear of the dispute and began to join the morning pickets before going to work. Apex declared the strike official and Grunwick offered reinstatement if the workers dropped union recognition. They refused and the company sacked a total of 137 strikers.

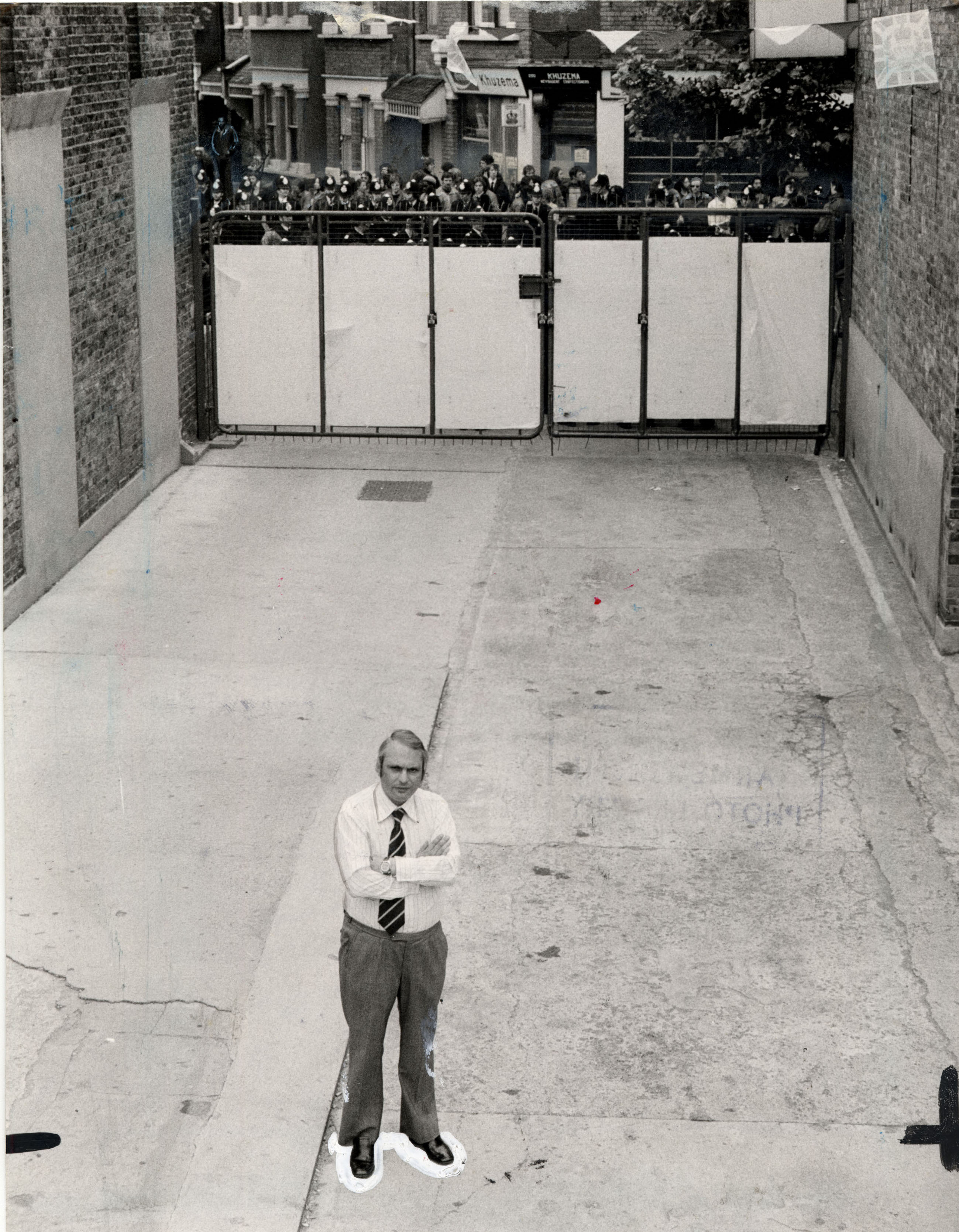

George Ward Grunwick Film Processing Plant Manager Who Has To Play Hide And Seek With The Chanting Pickets To Enter And Leave His Office In An Old Victorian House Next To His Main Works At Chapter Road Willesden.

Roy Grantham, general secretary of Apex, asked secretary of state Albert Booth to set up a court of inquiry into the dispute. The union then officially referred the dispute to the ‘conciliation service’ Acas, upon Booth’s advice. The local workers had other ideas, however.

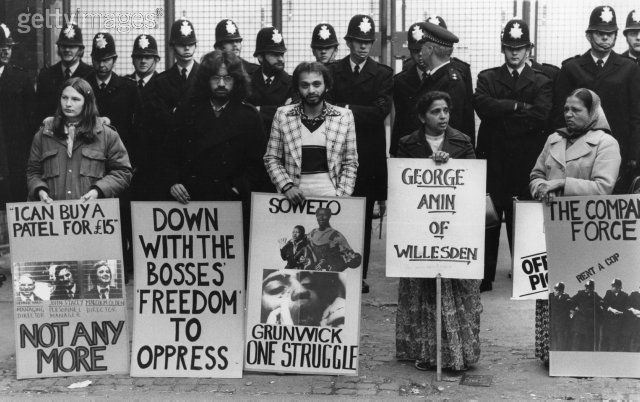

Grunwick’s business relied on holiday snaps, with film and prints sent by post, and on 1 November postal workers at the Cricklewood sorting office voted to refuse to handle Grunwick’s mail – the kind of spontaneous grassroots solidarity that was common at the time. George Ward promptly launched a legal challenge in the High Court, aided by the right-wing National Association for Freedom, a pressure group led by Conservative MP John Gorst which specialised in strike-breaking. They launched ‘Operation Pony Express’ to get Grunwick mail out of London and franked and sent by the Royal Mail, and were backed by the opposition leader Margaret Thatcher, who regarded them as champions of freedom. When Grunwick agreed to cooperate with Acas, the Union of Postal Workers (UPW) called off the blacking of mail under threat of legal action.

As the unions stepped back from the dispute, the strikers found themselves isolated. Desai took the initiative, telling a large strike meeting, ‘We must not give up!’. The strike committee began to tour the country, visiting over a thousand workplaces to ask for support. It worked, and the strikers managed to keep going through the winter.

Acas reported in March 1977, recommending union recognition and negotiation, but this was challenged by Grunwick and then overturned. The General Council of the TUC then turned down a request by Apex for blacking of essential services to Grunwick. In June, UPW members at Cricklewood and Willesden began an unofficial boycott of Grunwick mail and were suspended by the Post Office. The leadership of Apex and the UPW, who wanted to keep control of the dispute, threatened to stop strike pay and suspend strikers.

Mrs Joy Amon And Her Daughter Bobbie Whose Family Run Firm Glue Pen Company At Cricklewood Is Threatened With Bankruptcy Because Of The Blacking Of Grunwick Mail.

The strikers then turned to the tactic of mass picketing, and encouraged workers from all over Britain to join them outside the factory. The TUC’s main concern, by contrast, was to avoid embarrassing the Labour government, which had a slim majority and didn’t want any high-profile picketing. Despite its best efforts to discourage any escalation, the pickets began to grow, and as they did so the police increased their presence, too.

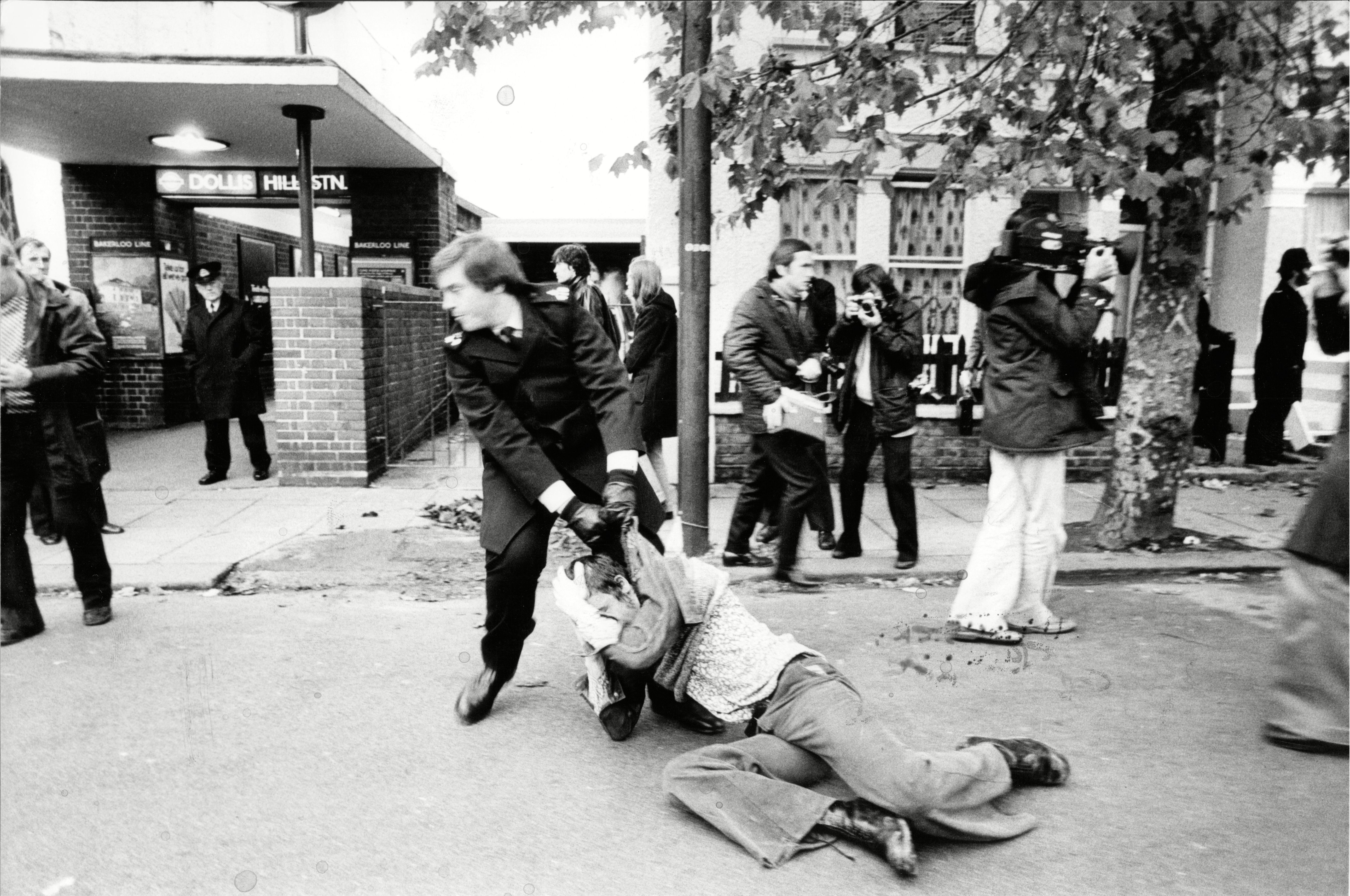

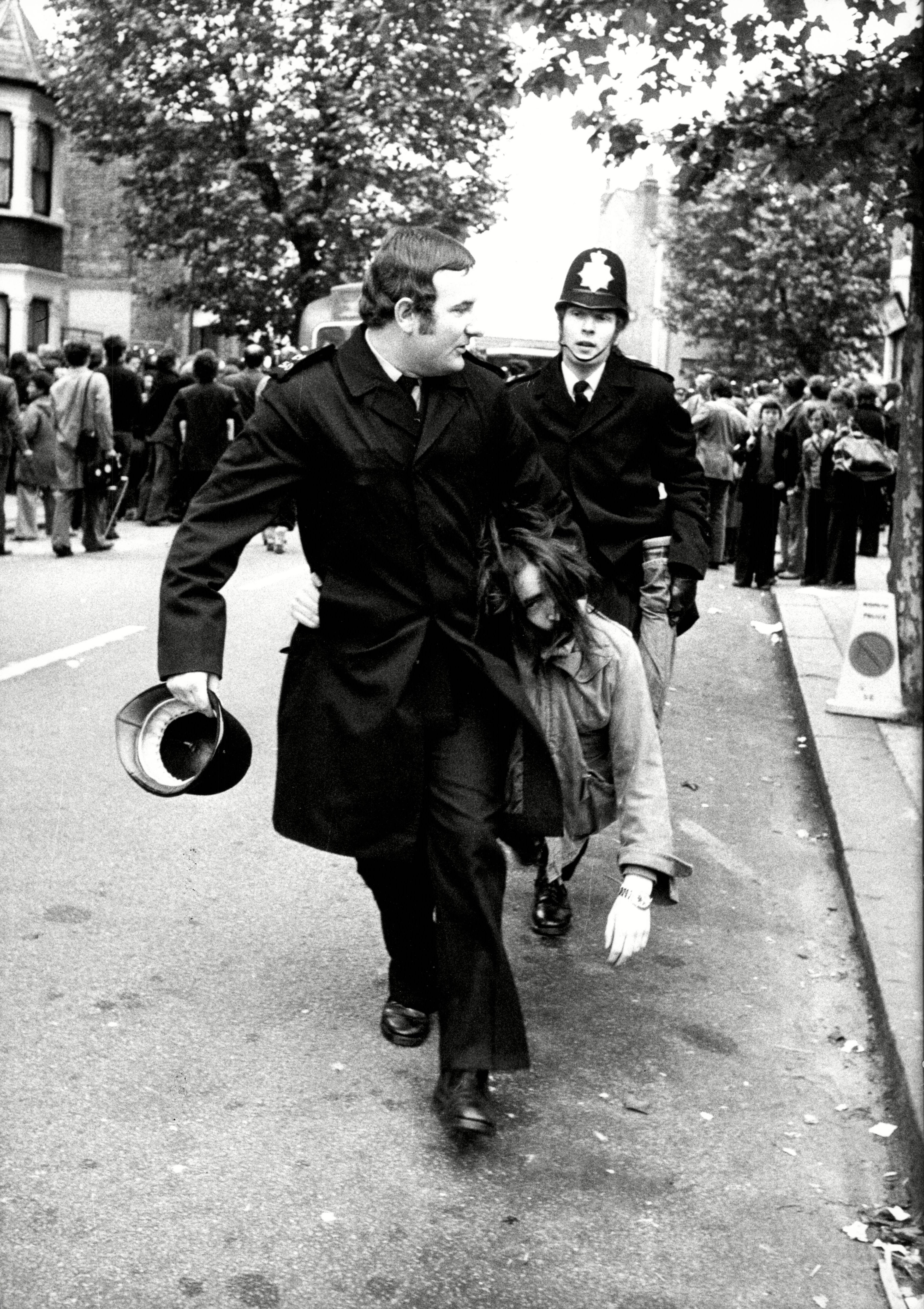

The policing of the strike was controversial from the start, and included several elements that would become familiar over the next decade. There was systematic surveillance of strikers, militaristic tactics on the picket lines, and careful manipulation of the public image, with prominent pictures in the press of injured officers. The day-to-day policing of the strike – from interpreting the law to prevent effective picketing to actively assisting the bussing in of scabs – was regarded by strikers as the action of a ‘company police’ in league with management. This belief was strengthened when a chief inspector retired in order to become a personnel manager at Grunwick.

Then there was the Special Patrol Group (SPG), the Met’s own ‘heavy mob’, who earned their notoriety at picket lines and demonstrations and in black inner-city areas. Tooled up with a cache of ‘unofficial’ weapons, they revelled in their thuggish reputation.

The first mass picket was designated a ‘women’s day’, which was intended to signal peaceful intent. It was met by a ferocious operation as police assaulted unarmed women and made more than 80 arrests. But the mass pickets continued, with scab buses driving into them at speed, and police picking off individuals for a beating. (At one point, Desai was taken to hospital after a management car ran over her foot.) There were more than 550 arrests during the strike – more than in any dispute since the General Strike of 1926. Interviewed years later about the policing of the Grunwick strike, the then-backbench MP Jeremy Corbyn reflected the delusional ‘workers in uniform’ attitude of the Labour left: ‘Most police officers are working-class lads. You’d say, what are you doing here, why are you defending these people?… “I’ve been told to do it.”… Well that’s not much of an answer is it?’

On 11 July, just after the suspension of the postal workers, the regular picket swelled to 12,000 and there was a TUC ‘solidarity’ march of many thousands more. This was the famous day that dockers, steel workers, rail workers and many others – most notably the Yorkshire miners and their leader Arthur Scargill (made famous by the use of ‘flying pickets’ at the so-called ‘Battle of Saltley Gate’) – were pictured in the packed streets, confronted by the massed ranks of the Metropolitan Police.

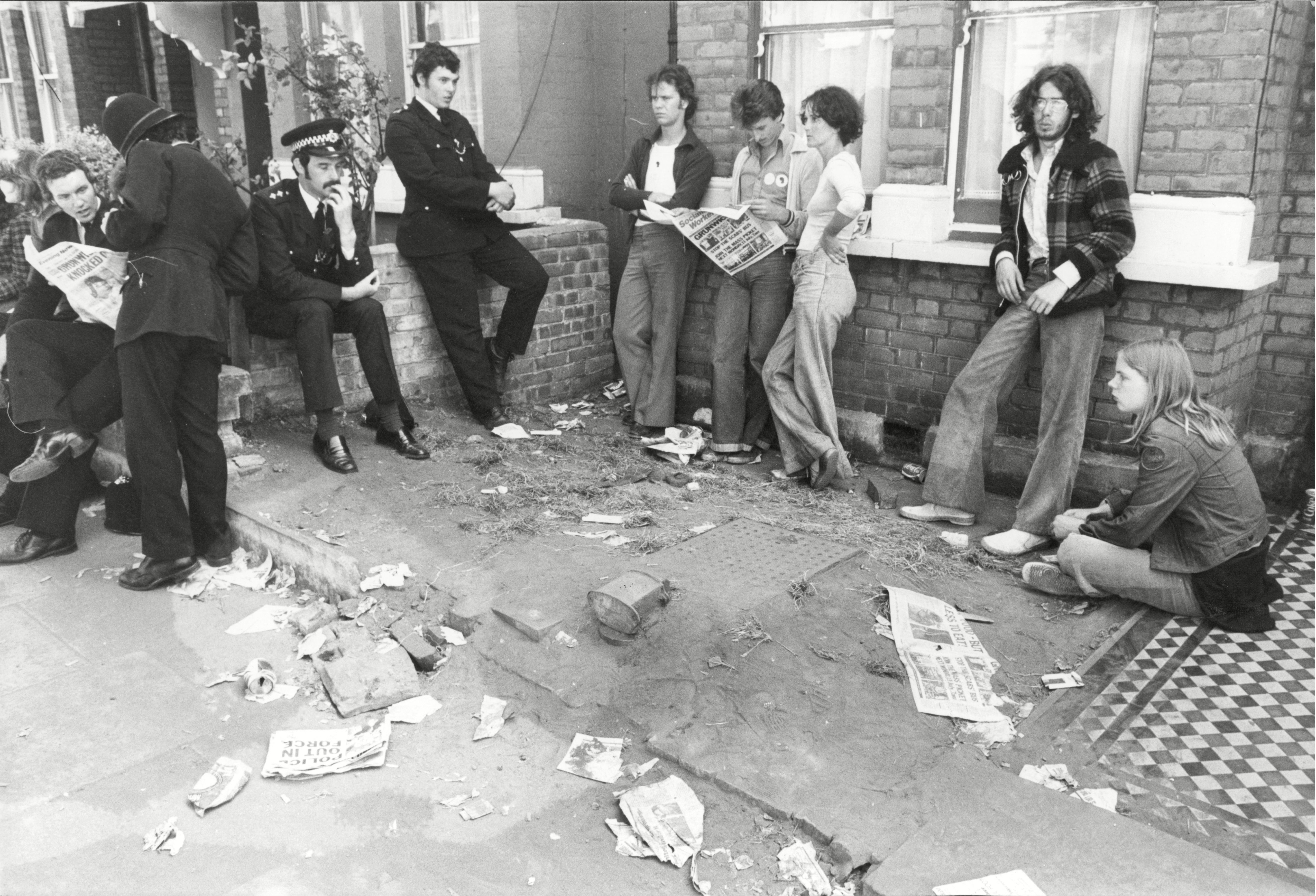

Mrs Lena Wood Surveys The Remains Of Her Front Wall After Clashes Between Police And Pickets At The Grunwick Factory

Prime minister James Callaghan set up a cabinet committee under Lord Justice Scarman to resolve the dispute. This was music to the ears of TUC general secretary Len Murray, who responded: ‘No employer has ever defied a court of enquiry.’ Jayaben Desai, unsurprisingly, saw things differently. ‘He will defy the court of enquiry’, she said.

She was right. Lord Scarman’s report recommended union recognition and reinstatement, but Ward refused to accept this. Apex lost enthusiasm for mass picketing and the TUC began to withdraw its ‘support’. On 21 November 1977, Desai and a few others defied their union’s wishes by beginning a hunger strike in front of TUC headquarters, to persuade them to disrupt water, gas and electricity supplies to Grunwick. The TUC ignored them and Apex suspended their memberships. On 14 December, the House of Lords upheld the decision to overturn the Acas report, and the legal process was complete. Six months later, on 14 May 1978, the strikers held a national conference at Wembley, and the following day, in a final snub, George Ward rejected an Acas proposal for a workplace ballot.

The strike was eventually called off on 14 July 1978, after almost two years. At the final meeting of the strikers, Jayaben told them they should be proud: ‘We have shown that workers like us, new to these shores, will never accept being treated without dignity or respect. We have shown that white workers will support us.’

She was right again. The strikers had shown great courage and determination. White workers had supported them in an era when other disputes, such as Mansfield Hosiery Mills in Nottinghamshire and Imperial Typewriters in Leicester, had been divided on racial lines. The dockers were associated in the minds of many with their march in support of Enoch Powell, yet they showed up in their numbers at Grunwick to display once again their tradition of solidarity with other workers. The Grunwick strikers, who came from a highly marginalised section of society, were surprised by the solidarity shown, and the fact that people were prepared to risk their own jobs for the cause.

Nevertheless, the strikers were under no illusions. The strike had failed in its objectives, which were union recognition and reinstatement. Worse still, it failed because the trade-union leadership ensured that it failed. This is often portrayed as a ‘sell-out’ or betrayal, but it was really nothing of the sort. The TUC behaved in accordance with its own principles at all times. It regarded itself as a pillar of government. Len Murray was as prominent and famous as the party leaders of the day, and was regularly impersonated by Mike Yarwood on primetime TV, as were other union leaders. The phrase ‘beer and sandwiches at No10’ referred to the way Labour ministers and trade-union leaders did business together in ‘smoke-filled rooms’. The TUC’s main concern was to secure its position at the centre of things, and wherever possible help the Labour government on whom it relied for its position. Ordinary union members were expected to accept whatever crumbs were brushed from the top table, and anyone who rocked the boat received short shrift.

In November 1977 four of the strikers staged a protest and hunger strike outside Congress House (TUC HQ) in protest at the decision of the TUC and APEX to withdraw their backing for the strike. Despite all the support they had received from ordinary workers up and down the country they were let down by the trade union establishment. Jayaben Desai commented “Trade Union support is like honey on the elbow – you can smell it, you can feel it, but you cannot taste it.”

This cosy situation was destined to come to an end over the following decade, and the warning signs were there at Grunwick. Right-wing businessmen and Thatcherite Tories weren’t interested in the old arrangements, and simply brushed them aside. Keith Joseph, a key figure in developing the Conservatives’ manifesto for the 1979 election, said that if the unions won, Grunwick would represent ‘all our tomorrows’.

The only way to win a dispute like Grunwick’s was to fight as hard and uncompromisingly against the employers as they were prepared to fight. The unions were determined that this should not happen, and swiftly took action against any of their own members who had the temerity to take industrial action.

‘The union just look on us as if we are employed by them’, said Desai at the end of the hunger strike. ‘They have done the same thing to us as Ward did.’ Regarding the TUC, she remarked: ‘They make the rules… We can’t make any hunger strike, we can’t make any demonstration, we can’t make any mass picket, we can’t do anything. Now it means they are going to tie the workers’ hands. We shall have no chance to do anything… it will apply to everybody, not just to the Grunwick strikers.’

Len Murray said later that the dispute had got ‘out of hand’: ‘There were calls for us to blacklist Grunwick’s post forever, drive the company out of business, and even turn off Mr Ward’s gas, water and electricity. All very illegal and very unacceptable to the majority of moderate British people.’

Residents Of Cooper Road N.w.16 Sweep The Debris Away From Their Front Door After The Grunwick Mass Picket

The irony of Grunwick was that in its heyday the TUC wasn’t even prepared to fight for the principle of union recognition from which its own power derived. By the end of the 1980s it was an irrelevance, and in the 1990s it was finally sidelined by New Labour. Its time had been and gone, and it had no purpose to serve. Today’s unions do little more than offer advice and put on the occasional pathetic ‘protest’ while employers impose working conditions and contracts that Grunwick’s management could only have dreamt of. Their reliance on European employment legislation is an implicit admission of impotence.

Meanwhile, the story of Grunwick has undergone a transformation. At one time the labour movement (which loves to romanticise defeats) would have seen it as an heroic failure – their version of ‘it’s not the winning, it’s the taking part’. There was even a folk ballad penned in its honour: ‘Hold the Line Again (The Grunwick Strike)’ by Jack Warshaw.

Today, however, it is celebrated as a sort of triumph. A victory for cultural diversity and the empowerment of women. A victory against racism, gender stereotypes, and the patriarchy of the traditional Asian family. And so on. If the actual workplace is mentioned at all in this new version of the tale, it is seen as the site of a struggle for ‘dignity’ and ‘human rights’, as became clear during a recent discussion of Grunwick on Radio 4’s Today programme.

Local Labour MP Dawn Butler wrote recently of the Grunwick legacy:

‘Times have changed, and although the leadership of almost all the trade unions are still white men, these men are enlightened and are the leaders at the forefront of the struggle against inequality and discrimination. They now recognise that the concerns of migrant workers are also their concerns… This, in my opinion, is the real legacy of Grunwick. I often hear the strikers say that they failed. I have told them as forcefully as I could that they succeeded in so many ways and their legacy lives on in people like me, an African-Caribbean woman who was a full-time trade-union official.

‘Never again should we sit back while a group of people are fighting for equality and better working conditions. Following the referendum decision to leave the EU and the subsequent uncertainty about workers’ rights, and amid rising levels of racism and abuse towards minorities, this lesson is more important than ever.’

The unions themselves have got in on the act with enthusiasm. The GMB (into which Apex was incorporated) has its own Grunwick anniversary exhibition, and general secretary Tim Roache is effusive: ‘The strike contained the essence of all that is best in the labour and trade-union movement. For, what we do is not about cynical calculation, it is not about profit and loss, or momentary advantage. It is about decency. A decency that sees the value in every human being, regardless of their background or the colour of their skin. It is a sense of decency that unites us in common cause and fights for universal values. It’s the thing that brings us together, in the trade unions, and keeps us going through the hard times.’

Note that it is the strikers themselves who tell Butler that the strike failed. Likewise, in a recent radio documentary, the programme-maker Maya Amin-Smith says how amazed she was to discover that members of her own family were involved in the strike, but had never mentioned it. One of these women tells her that she never thinks about the strike (‘We forgot everything now’). Amin-Smith is shocked by this. For her and other younger Asians, Grunwick is a symbol of everything positive. For the old woman, it holds no special significance.

This is not to belittle the positive impact these women undoubtedly made on society. The Grunwick dispute helped to change attitudes, and had all kinds of important side-effects. But that’s not what they were actually fighting for. The celebratory talk of race and gender allows those responsible for the defeat – the Labour Party and the unions – to skate over their own actions and paint themselves in a favourable light. The GMB website acknowledges the strike’s failings as follows:

‘The trouble was that the labour movement and the Labour Party put too much faith in the law, and in procedure. The judgments of Acas tribunals and the Scarman – government-backed – Inquiry all found in favour of the strikers and their right to join a union. But the bosses simply ignored them and the movement blinked first. Defeat is always bitter, but it is only fatal if we fail to learn the lessons.’

The fact is that the unions didn’t ‘blink’; they washed their hands of the strikers by pushing for arbitration and then pressurised them into abandoning their activities. As for learning lessons, they no longer simply put ‘too much faith in the law, and in procedure’ – they put all their faith in it.

Jayaben Desai died in 2011. In her later years she was hailed as a role model for female Asian workers in disputes such as those at Futters (light engineering) and Chix (confectionary). She was praised for her ‘dignity’. She was showered with awards, including a ‘gold award’ from the GMB, honorary membership of the Communication Workers Union, a citizen’s award from Brent Council, and now the plaque on the flats. She probably got a Blue Peter badge, too. One of her many pithy remarks springs to mind. The strikers, she said, had ‘drowned in sympathy, but thirsted for action’.

‘We Are The Lions’ is at Brent Museum & Archives, The Library, 95 Willesden High Road, NW10 2SF, until 26 March 2017.

This story features on Spiked – the site you should be reading.

Photos via Grunwick 40.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.