“Life Begins at the Baby Incubator”

– Sign at Coney Island’s Lunar Park advertising Dr Martin Couney’s Live Babies Show

By the tents hosting the Four-Legged Woman, penny peep shows, and Lionel the Lion-Faced Man (him you’ve gotta see), thrill seekers to Coney Island’s Luna Park with 25 cents to spare could gave upon Lucille Horn, one of hundreds of “LIVE” premature human babies in glass incubators.

Lucille weighed 2lbs when she was born in 1920. Her twin sister died at birth. All the experts told Lucille’s parents to expect the worst. She’d be lucky to live a month. Lucille died on Feb. 11 2017. She was 96.

“They didn’t have any help for me at all,” she recalled in 2015. “It was just: You die because you didn’t belong in the world.”

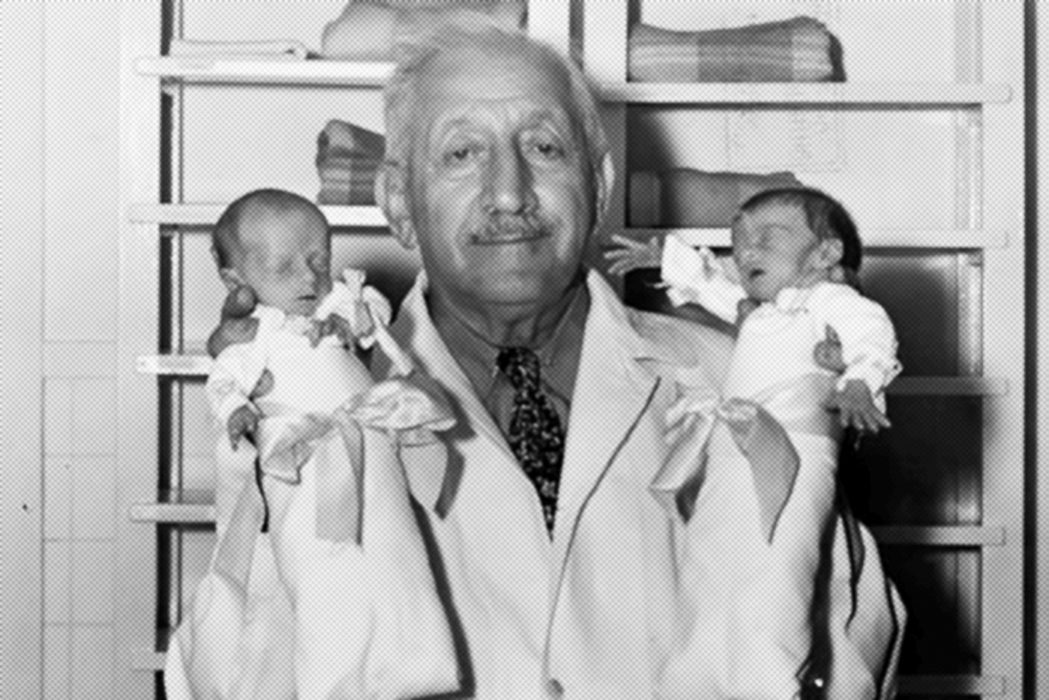

Martin Couney (nee Cohen) had other ideas. Eschewed by the medical establishment, the money from his sideshows paid for research into infant mortality. A skilled publicist who showcased his incubators at fairs throughout America, news of his work travelled far. “All my life I have been making propaganda for the proper care of preemies, who in other times were allowed to die,” he told The New Yorker’s A.J. Liebling in 1939.

Lucille’s father heard the news. He asked the doctor to help his daughter. “I’m taking her to the incubator in Coney Island,” Mr Horn told the medics caring for his daughter in a Brooklyn hospital. The doctors told him there was not a chance in hell that she’d live. “But she’s alive now,” he replied. He hailed a cab and took his daughter to Dr. Couney.

There’d be no charge. Couney never charged for his services. Six months later, Horn was healthy enough to go home. Years later, she paid the entrance fee and visited the sideshow.

“And there was a man standing in front of one of the incubators looking at his baby,” she recalled, “and Dr. Couney went over to him and he tapped him on the shoulder. “He said, ‘Look at this young lady. She’s one of our babies. And that’s how your baby’s gonna grow up.’ ”

He knew then. And he’d known before. Couney’s own daughter was born prematurely, and she too spent time in one of her father’s Coney Island exhibits.

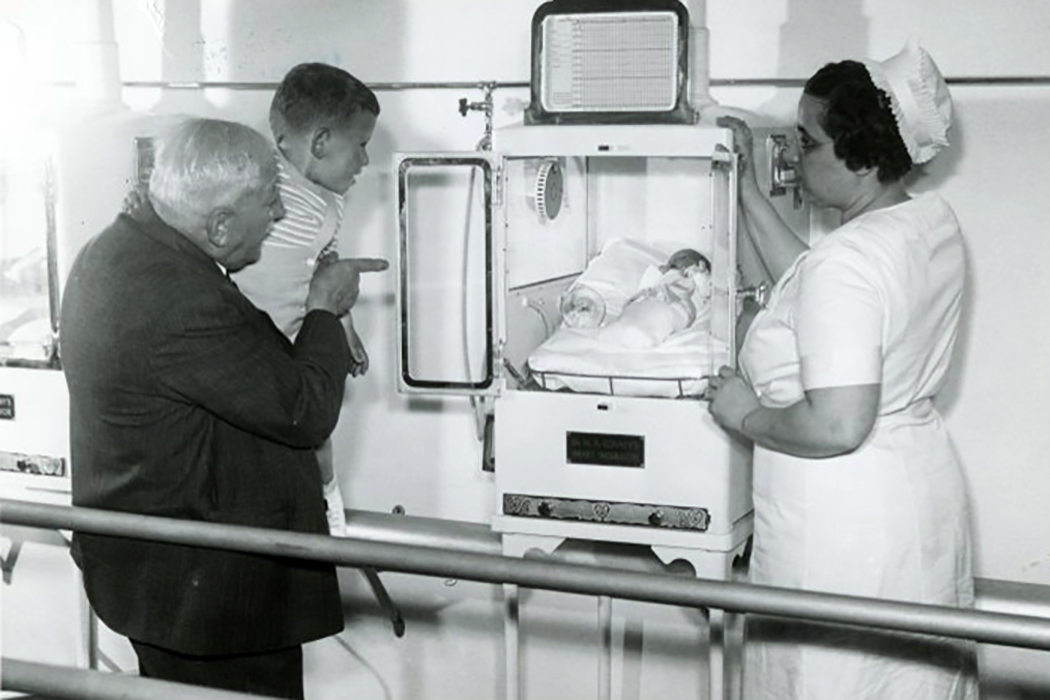

Reporting in 1903, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle described the “seriousness and value of the system shown.” A visit to Couney’s showcase revealed rows of warmed, glass-fronted incubators supplied with filtered air, containing “little pitiful pinched looking waifs… the only things that indicate that they are alive are the healthy color of their little faces and the faint flutterings of movement which are perceptible on closer inspection.”

By one estimate, Couney saved the lives of 6,500 infants.

Eugenics and Death by Design

Dr Couney wasn’t the first to see the value of incubators in human health. In the late 1870s, French obstetrician Dr. Stéphane Tarnier (1828–1897) observed baby chickens in an incubator at a Parisian zoo. Perhaps he could use the same method to treat premature babies dying of hypothermia in Parisian hospitals.

After advances in ventilation and monitoring, in 1896, at the Berlin Exposition, Couney saw for the first time the new glass and metal incubators keeping premature babies alive. He vowed to take the technology to the United States, where they were extremely rare. Incubators were shown at expositions in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1898, and Buffalo, New York, in 1901.

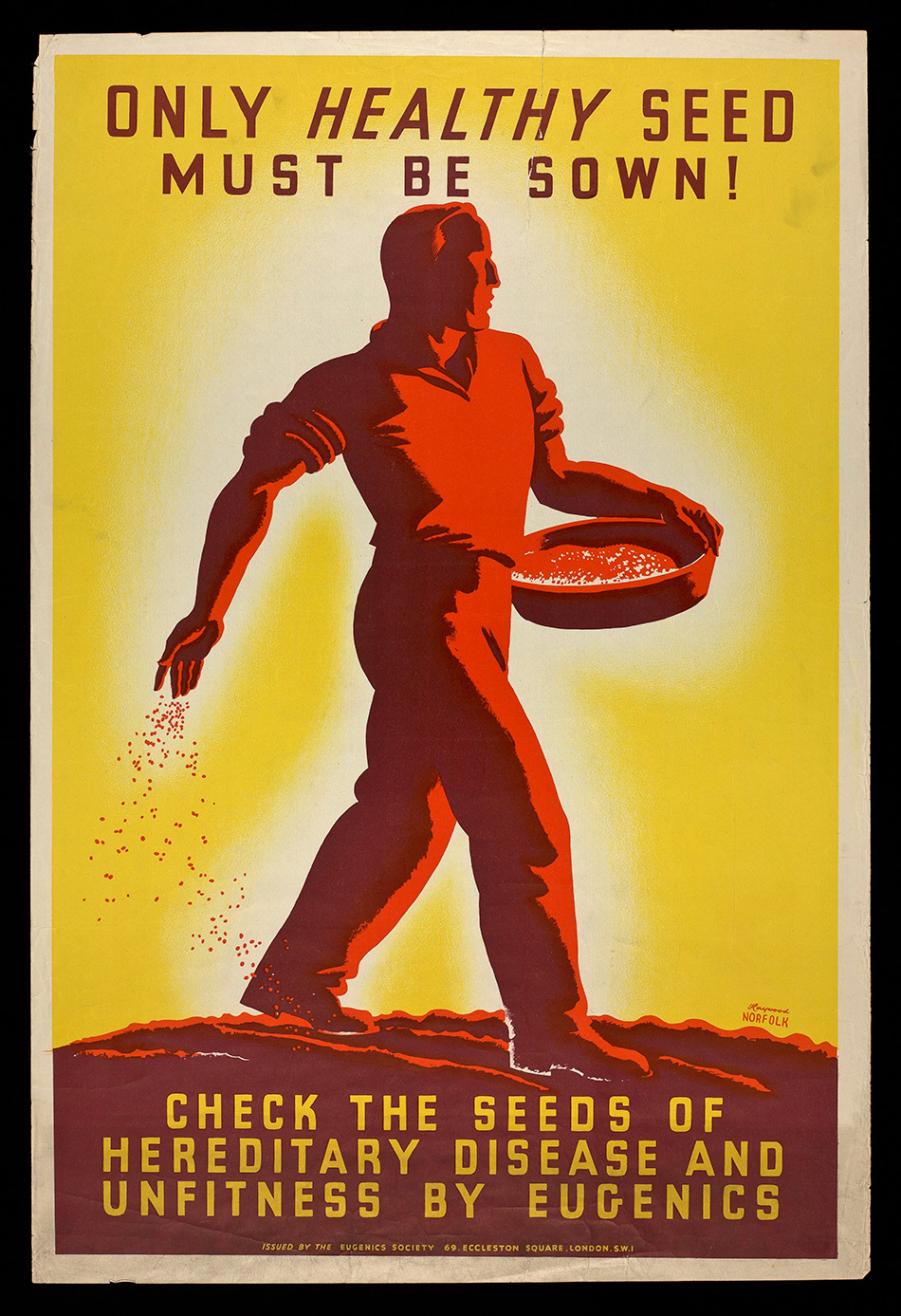

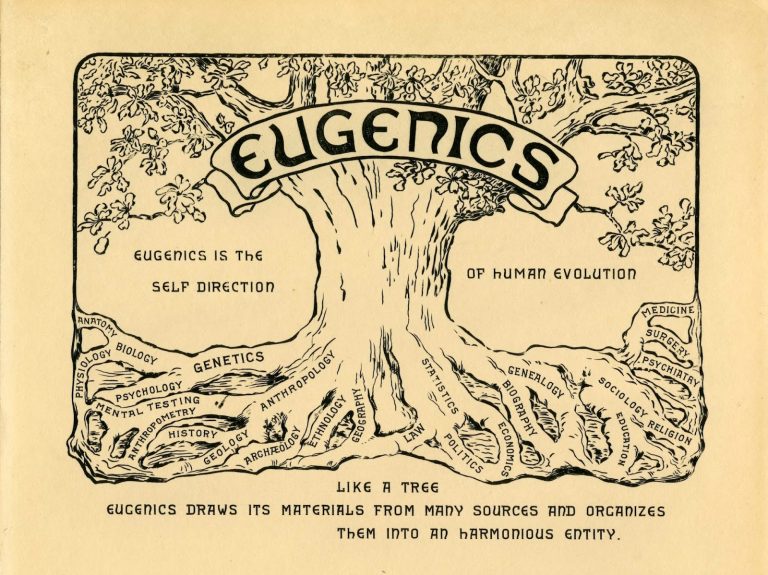

American hospitals were slow to adopt incubators for a variety of reasons. A 2000 article on the subject in the Journal of Perinatology cited, among other factors, the belief among early-1900s infant care experts that premature babies were weaklings who, if they survived, were likely to pass on that trait to their own children.

1920s eugenics poster

This was the age when eugenics was in vogue. An article in a 1913 issue of Woman’s Home Companion explained the eugenicists’ mission:

“Underneath the inviting charm of the idea is a serious scientific purpose — healthy babies, standardized babies, and always, year after year, Better Babies.”

Eugenics beauty contests set out to find the perfect boy and the perfect girl who togethter would create the perfect human. The magazine published a scorecard and formed the Better Babies Bureau to encourage community groups to hold their own contests.

Many people you think would know better championed selective breeding that created a hierarchy of humans and led to the gas chambers of the Nazi concentration camps, including Irish writer George Bernard Shaw, Britain’ wartime leader Winston Churchill, William Beveridge, the architect of Britain’s post-1945 welfare state, Theodore Roosevelt, 26th president of the United States, Marie Stopes, the family-planning pioneer and writer H.G. Wells.

Kathy and Beth’s Stories

Beth Allen was born 3 months premature at a hospital in Brooklyn. She weighed 1 pound 10 ounces:

“My parents knew about the incubator baby “’sideshow’ in Coney Island and were reluctant to send me there . Couney came to the hospital and spoke to my mother and she agreed to put me under his care.”

Allen spent three months on show at Luna Park. She weighed five pounds when she left.

“Although I have just a vague memory of his house, my parents and I visited Dr. Couney every Father’s Day for several years.”

To celebrate the success of Beth, Lucille and many others, Couney organised a “Homecoming” celebration on July 25, 1934, for babies who had “graduated” from the incubators at the Chicago’s World’s Fair the previous summer. Of the 58 babies Couney had cared for in 1933, 41 returned with their mothers for the reunion. The event was broadcast live on local radio and across the fairgrounds.

On the radio program, Couney’s exhibit was portrayed by the announcer not as a frivolous sideshow spectacle, but as an invaluable medical facility:

The Incubator station for premature babies…is not primarily a place of exhibiting tiny infants. Instead, it is actually a lifesaving station, where prematurely born babies are brought from leading hospitals all over the city, for the care and attention that are afforded. The place is spick and span, with doctors and graduate nurses in constant attendance…

Kathy Meyer was born eight weeks premature in 1939. She was taken to the new premature infant centre at Cornell University’s New York Hospital. When Meyer’s parents were told she’d need to stay in the hospital for several months and realizsed they couldn’t afford to pay the bills, her doctor suggested they send her to Martin Couney at the New York World’s Fair. Couney sent his incubator ambulance to the hospital to collect her.

“I was a sickly baby,” said Meyer. “If it wasn’t for Couney, I wouldn’t be here today. And neither would my four children and five grandchildren. We have so much to thank him for.”

The Dr who Wasn’t

Couney never qualified as a medical doctor. He said he had studied medicine in Leipzig and Berlin. He immigrated to the US in 1888 at 19 years old. Claire Prentice dug deeper:

But someone of that age would not be old enough to have studied at university in Leipzig and Berlin before going on to do graduate work in Paris at the knee of Pierre Budin, the father of European neonatal medicine, as Couney claimed to have done in numerous press interviews.

In the 1910 U.S. census, Couney listed his career as, “surgical instruments.” Though Couney claimed to be the inventor of an incubator, I have been unable to find any evidence that he registered an incubator patent in the U.S. More likely Couney was a technician. Yet by 1930 he was describing himself in the census as a “physician.”

…

The distinguished Yale professor, pediatrician and child developmental psychologist Arnold Gesell visited Couney multiple times at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Gesell brought a cameraman with him to film the babies in Couney’s facility.

Interestingly, when Gesell wrote his book, The Embryology of Behaviour: The Beginnings of the Human Mind, he avoided any mention of Couney or the sideshow setting where he had carried out much of his research. By contrast, when in 1922, Hess [Chicago pediatrician Dr. Julius Hess] wrote the first textbook on premature birth published in the U.S., Premature and Congenitally Diseased Infants, he wrote, “I desire to acknowledge my indebtedness to Dr Martin Couney.”

Martin Couney (born Michael Cohen, 1869 – March 1, 1950) was an American obstetrician of German-Jewish descent, an advocate and pioneer of early neonatal technology.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.