George Hanson : They’re not scared of you. They’re scared of what you represent to ’em.

Billy : Hey, man. All we represent to them, man, is somebody who needs a haircut.

George Hanson : Oh, no. What you represent to them is freedom.

– Easy Rider (1969)

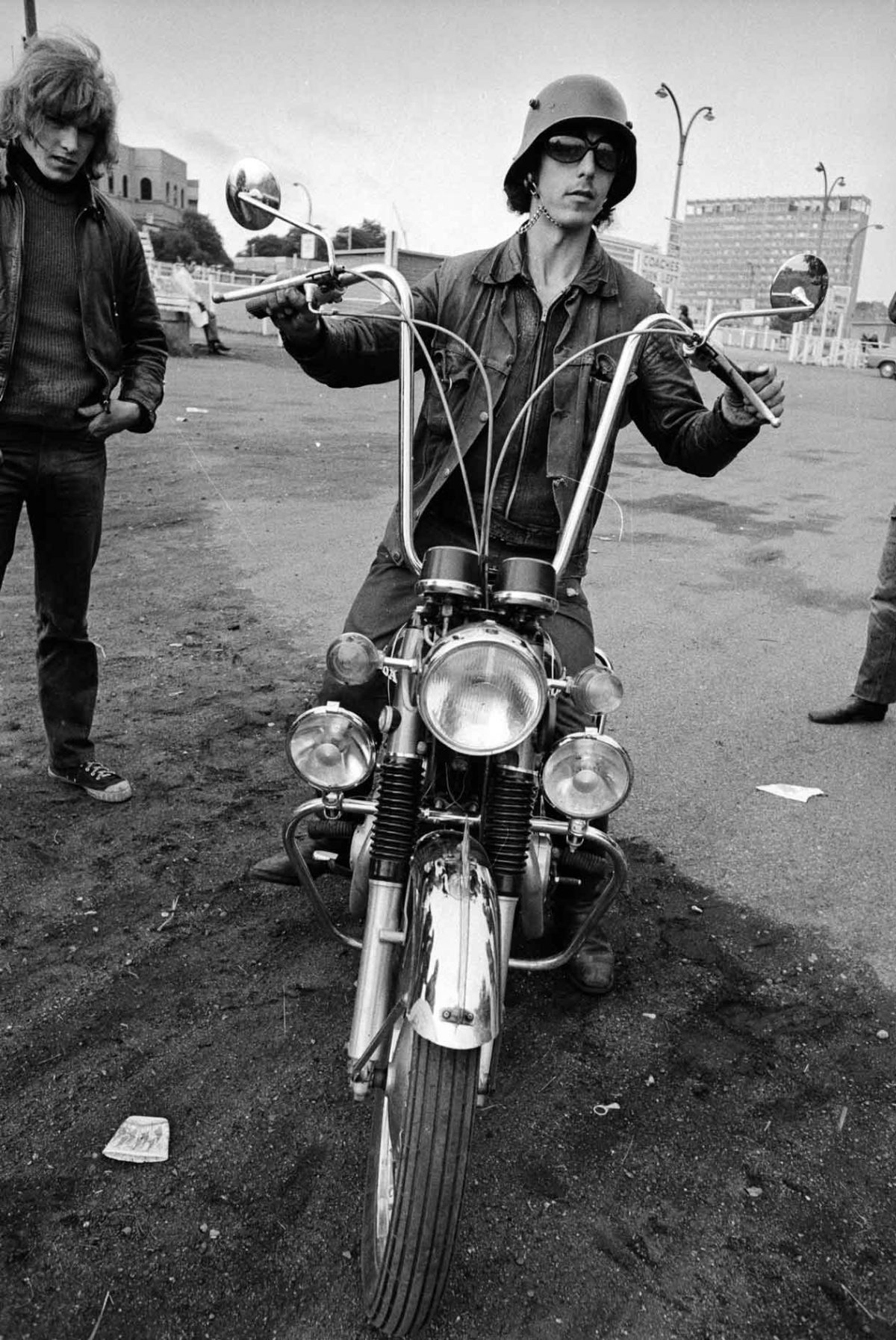

The golden age of the Chopper reached its peak in 1969, with the release of Dennis Hopper’s cult classic Easy Rider. The bikes used in the movie, says Paul d’Orleans, author of The Chopper: The Real Story, “did more to popularize choppers around the world than any other film or any other motorcycle… suddenly people were building choppers in Czechoslovakia, or Russia, or China, or Japan.”

The mean-looking machines, with their shimmering chrome and aggressively guttural engines, were a pure product of “the ultimate American folk art movement.” Choppers emerged, d’Orleans writes in his introduction, from “a culturally explosive mashup of particularly American traits; the cowboy/outlaw, free of family, property, or history, free to explore endless highways, free to express one’s individuality through dress and choice of transport.”

Easy Rider summed this with its custom-made motorcycles, especially “Captain America,” the bike Peter Fonda rode in the film, called thus because of the stars and stripes painted on its gas tank. “Someday it was inevitable,” wrote Roger Ebert in his glowing review, “that a great film would come along, utilizing the motorcycle genre, the same way the great Westerns suddenly made everyone realize they were a legitimate American art form.”

Choppers developed from a decades-long tradition of modifying motorcycles to make them lighter and faster, beginning in the early part of the century with so-called “bob jobs” or “bobbers.” Riders removed fenders, windshields, mirrors, even front brakes and speedometers—“anything that isn’t required to make it go,” writes Jonathan Strickland at How Stuff Works. When U.S. veterans returned from World War II, they took it even further. “Veterans sought out motorcycles like the ones they saw or drove during the war—they’d buy a bike and then modify it to make it more like the ones they used to ride.”

Of course, the ridiculously long forks and long banana seats didn’t resemble anything issued by the U.S. military. These laid-back innovations came from motorcycle clubs and bike builders in California, who exaggerated the features of drag racing bikes until choppers took on the weird proportions that made them famous. “In the 1950s, aesthetic motives had triumphed over speed,” notes Wolfgang Wild.

Not every chopper is the same, but typically a chopper will have features that include those extended forks, “ape hanger,” handlebars, no rear suspension, and an extended rear protection tube known as the “sissy bar.”

Bike builders take special pride in their unique designs; no two choppers are alike in their shape, size, and color scheme. As for “Captain America,” the bike most responsible for spreading the chopper craze around the world, its creation has been a matter of some dispute, and some deservedly hard feelings. “Curiously,” says d’Orleans, “the Easy Rider bikes were never associated with any particular builder.”

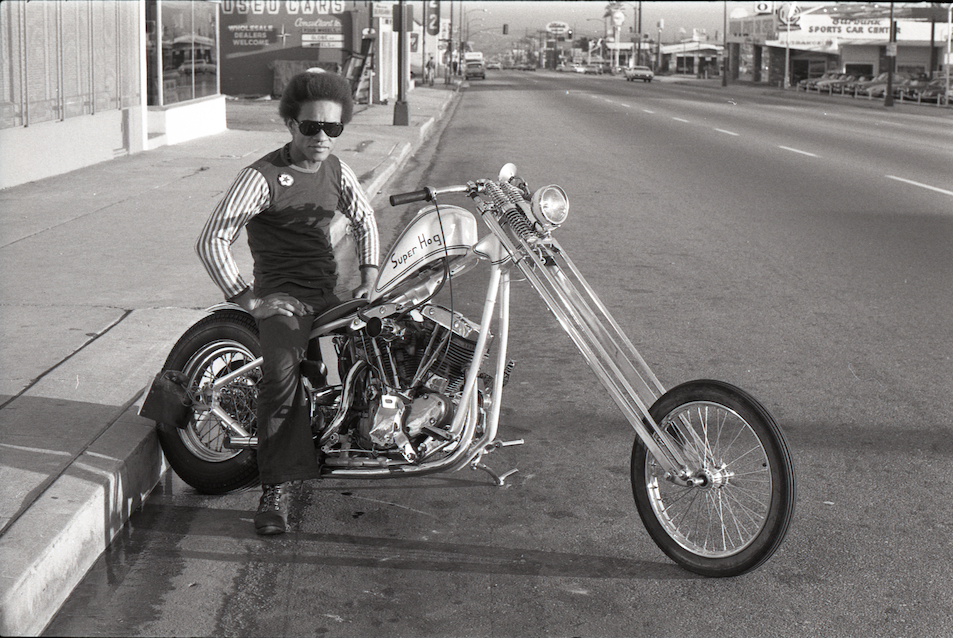

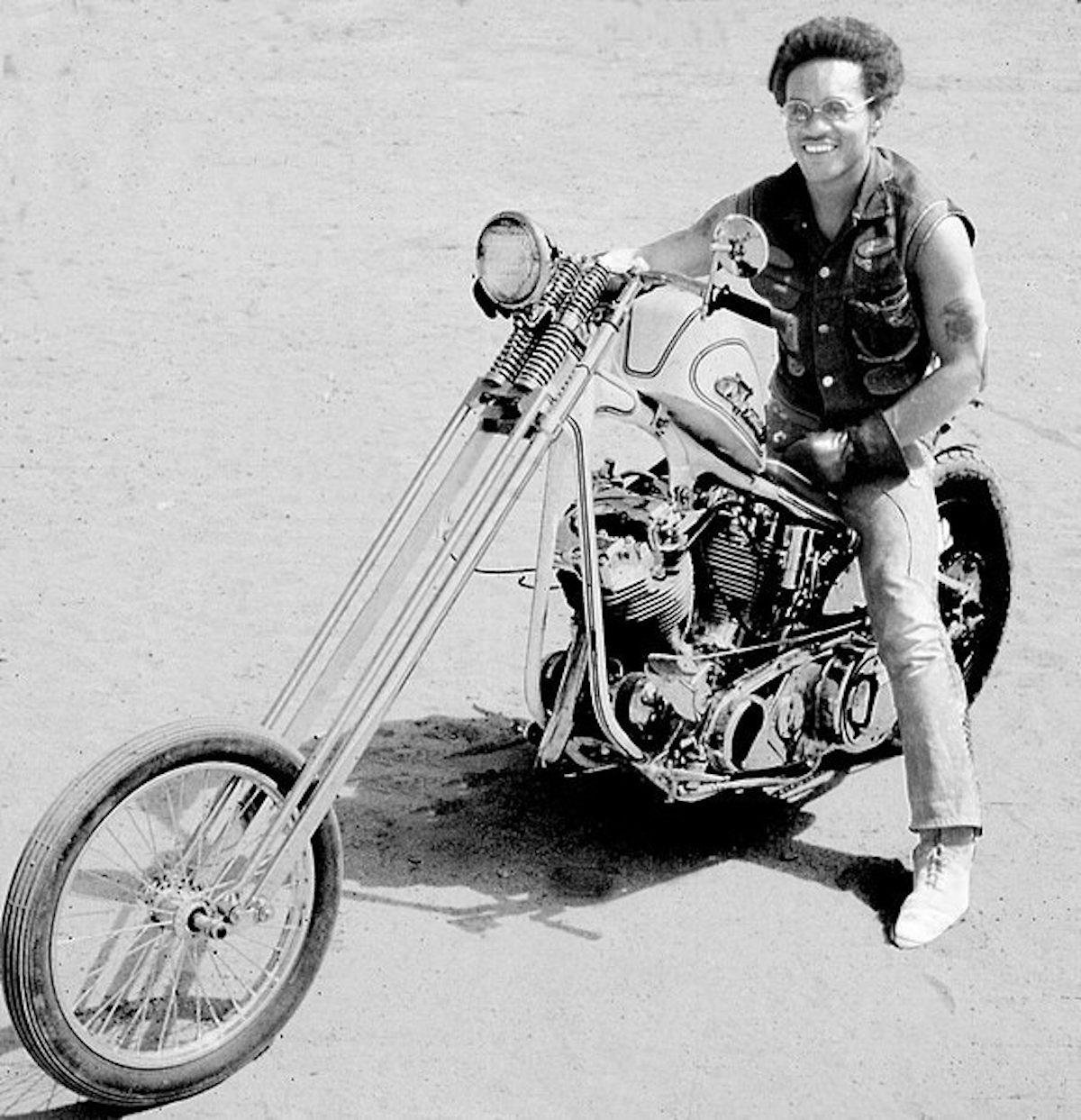

Peter Fonda took credit for the film’s bikes in a 2007 interview. But the real builders of the bikes have been identified as Ben Hardy, a prominent African American builder in L.A., and Clifford Vaughs (below – April 16, 1937 to July 3, 2016), a designer, journalist, photographer, and civil rights activist who had been riding and building choppers since 1961. Removed from the film early in the production, neither of them received credit.

Photograph by Danny Lyon of Clifford Vaughs arrested by the National Guard at a Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) protest in Cambridge, Maryland in 1964. In foreground, Stokely Carmichael pulls Vaughs’ right leg from Guardsmen

“I’m a little miffed about this, but there’s nothing I can do,” says Vaughs. What irked him more was the absence of black characters in the film, when chopper culture of the 1960s, he says, was as multi-racial as the country it came from. (Learn more about Hardy and Vaughs’ contributions in the clip from the documentary History of the Chopper.)

Easy Rider may have whitewashed chopper history, but the error has been corrected by the National Motorcycle Museum, which has displayed both Captain America and one of the “Billy” bikes Hopper rode in the film with the true story of their creation, adding some significant context about the level of Vaughs’ involvement in the movie’s development, such as his suggestion of the title and the use of his “real life adventures riding a chopper through the South in 1963.”

As Dennis Hopper himself noted, “like with Rock n’ Roll, the African-Americans were way ahead of us [on choppers].” In the ensuing decades, the chopper had its appeal for both black and white musicians, from Greg Allman and Sly Stone to – maybe most famously – the Purple One himself, whose custom 1981 Honda had a definite chopper vibe despite non-chopper extras like the fancy windshield.

Greg Allman on his chopper

Sly Stone rides his chopper

Prince on his Purple Rain motorcycle

Photo by Peter Pittilla:

The Village Of Gin Pit Lancashire, England. Children Of The Village With Raleigh Chopper Bikes – 8 Jan 1973

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.