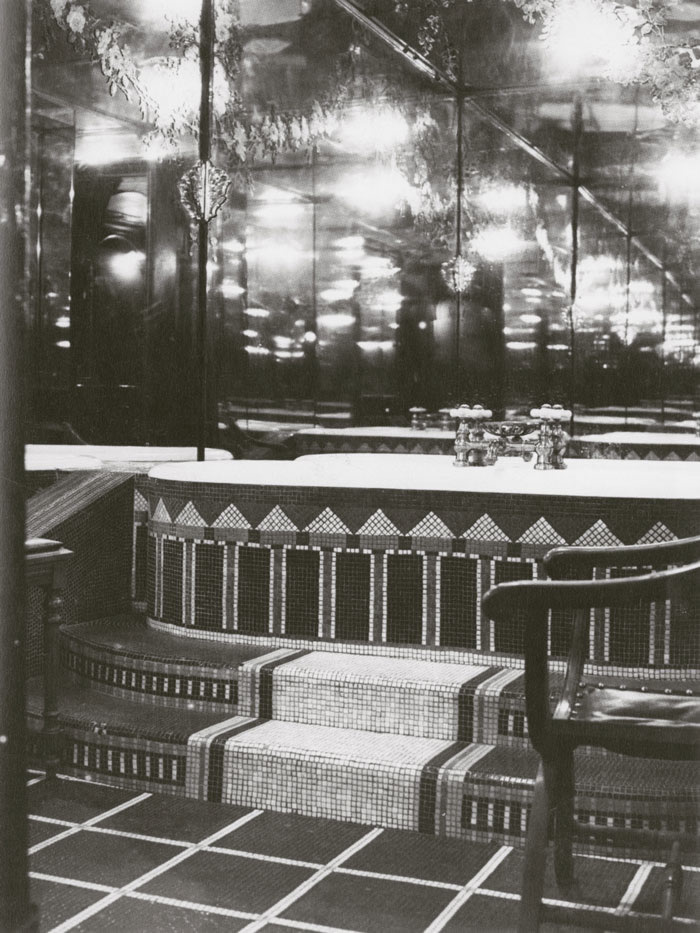

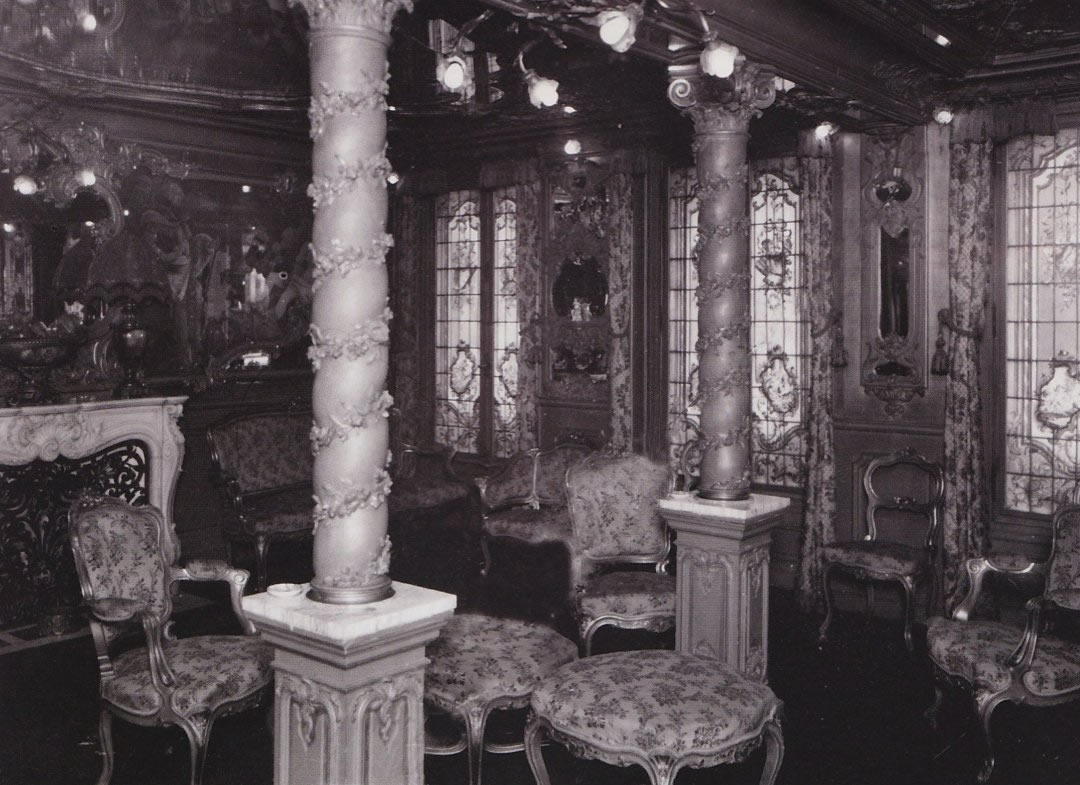

The most notorious brothel in France was the sophisticated Le Chabanais near the Louvre in Paris, renowned for famous visitors such as Cary Grant, Humphrey Bogart and Marlene Dietrich, who arrived on the arm of Erich Maria Remarque, the handsome author of All Quiet on the Western Front. The rooms were so splendid that one, decorated in the Japanese style, won a design prize at the 1900 World Fair in Paris.

In Germany the premier brothel was the infamous Salon Kitty, located at 11 Giesebrechtstrasse in Charlottenburg, a wealthy district of Berlin. It was run by Katharina Zammit, better known as Kitty Schmidt, whose house of ill repute is remembered for being taken over by the SS to spy on German dignitaries in the 1930s. One client was propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels who particularly enjoyed the ‘lesbian displays’ making an exception to what was usually considered a degenerate and ‘anti-social’ act in Nazi Germany.

In America, men flocked to the infamous Mahogany Hall in New Orleans, housed on Basin Street beneath castle-like turrets. Jelly Roll Morton was the house pianist and E. J. Bellocq’s surviving Storyville photographs of the bordello are evidence of the elegant furnishings, glittering chandeliers and Tiffany stained-glass windows.

Britain’s most infamous brothel, however, was situated in Streatham in a house at 32 Ambleside Avenue. It was a stone’s throw from the Streatham High Road, which, due to its ‘run-down shop fronts, broken lighting, cramped and broken pavements and an ever-growing number of yellow Metropolitan police signs advertising violent crime’, was once voted the worst street in Britain.

It was run by Britain’s most celebrated madam, Cynthia Payne – once pronounced by Jeffrey Bernard in the Spectator as ‘the greatest Englishwoman since Boadicea’. She first became front-page news in 1978 when, after an anonymous tip-off, the police raided her ‘respectable’ net-curtained home and found a queue of fifty-three, mainly elderly, clients. They were old because pensioners received a generous £3 discount and men under forty were banned – ‘All Jack-the-lads boasting about their prowess,’ Cynthia once maintained.

The men, some of whom were dressed in lingerie, included vicars, lawyers and politicians, all patiently waiting to see the thirteen prostitutes on the premises. A sign in the kitchen read, ‘My house is clean enough to be healthy … and dirty enough to be happy.’ The cleaning was usually done, often happily naked, by Slave Rodney and Slave Philip, both married men. To restore the clients’ limited energy at the end of the ‘parties’, the men all received mugs of hot steaming Bovril, served by ex-squadron leader Robert ‘Mitch’ Mitchell Smith – Cynthia’s devoted friend – who sported an RAF moustache but was often dressed as a French maid.

The notorious ‘House of Cyn’, as it came to be known, was celebrated neither for its luxurious surroundings – the interior was particularly chintzy, with antimacassars on the backs of the armchairs and flowery china ornaments and teacups on the shelves – nor the beauty of its women.

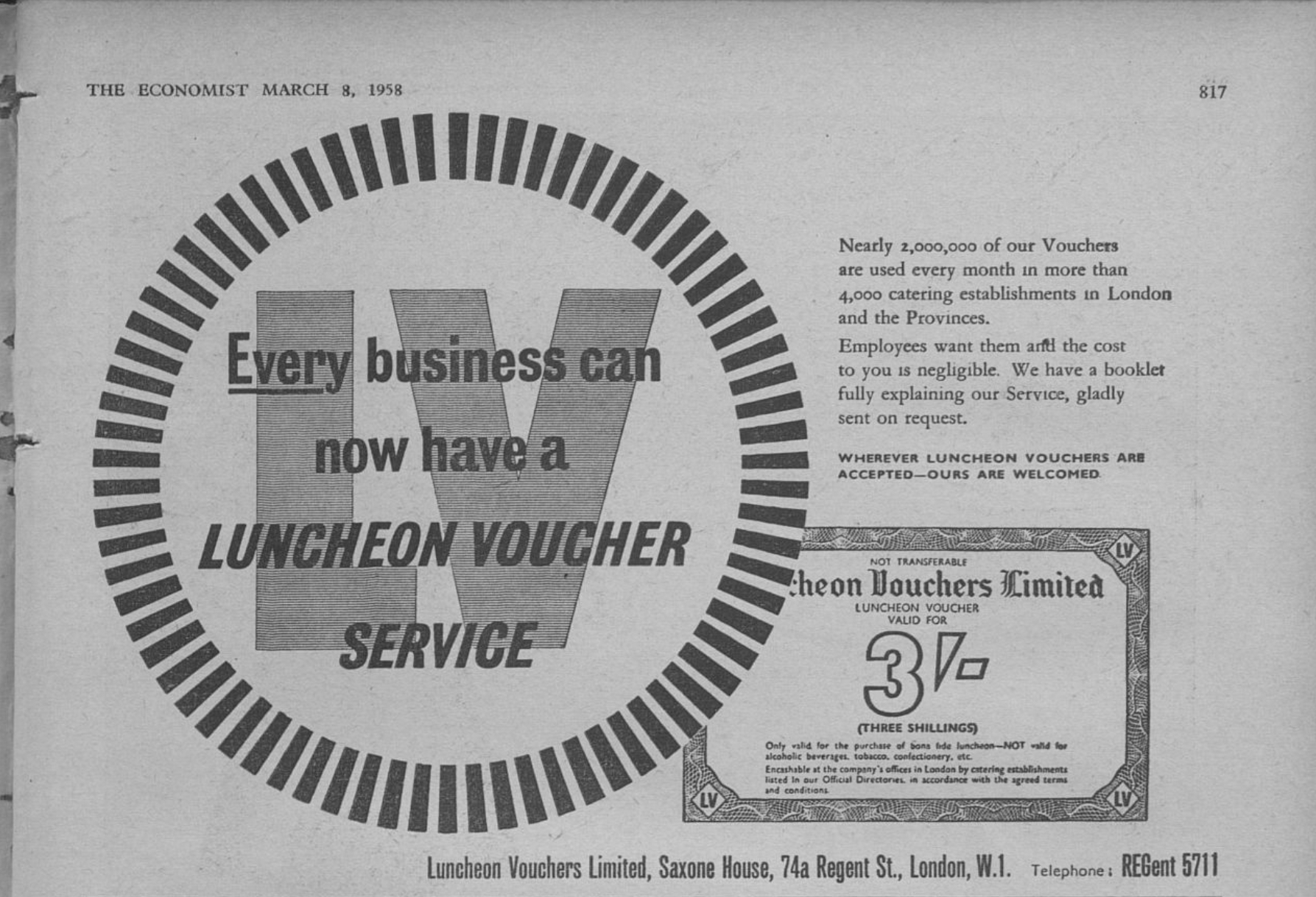

The brothel’s infamy came from the method of payment used: the luncheon voucher. Cynthia hadn’t always used luncheon vouchers. She originally used little plastic badges that she bought from the stationery chain Ryman. The clients paid an entrance fee and received a Ryman badge in return. The men would later give the badge to the women upstairs and they, in turn, would redeem them for cash from Cynthia as proof of services performed.

This all worked like clockwork until some women started buying their own badges from Ryman’s. Cynthia solved this problem when she came across an old box of out-of-date luncheon vouchers which were far harder to counterfeit. When the police raided her 1978 Christmas party, each of the men waiting on the stairs had a luncheon voucher in his pocket.

Luncheon vouchers were once ubiquitous, especially in the 1960s and 1970s. Most restaurants, pubs and cafés, to show that they accepted them as payment, had a green LV sticker in the window. They were introduced as a tax concession by the Labour Government in 1946 (the same year a teenage Cynthia was expelled from her convent school for continually ‘talking dirty’ and generally being a ‘bad influence’) in the hope that they would encourage citizens to eat more healthily. In 1948 the tax relief was raised a few pence to three shillings (15p, but worth approximately £5 in 2017), which would have bought you a reasonable lunch back then.

Cynthia was born on Christmas Eve in 1932 in Bognor Regis, West Sussex. Her father was a strict, albeit often absent, man called Hamilton who worked as a hairdresser on Union-Castle liners. Her mother, Betty, died of cancer when Cynthia was just ten, and she and her sister Melanie were brought up by a series of housekeepers. Cynthia’s first job, in 1949, aged sixteen, was at a bus garage in Bognor, followed soon after by an attempt to follow her father’s footsteps and become a hairdresser. She started training with some hairdressing friends of her father’s in Aldershot, but because of her incessant swearing they insisted she saw a psychiatrist. After lying that she was pregnant and subsequently threatening to swallow some weedkiller, Cynthia was eventually disowned by her father.

Jobs as a waitress and then a shop assistant in Brighton soon followed. At the age of seventeen she began an a air with a married man not much younger than her father called Terence, and this was the period of her life that featured in the 1987 movie Wish You Were Here, starring Emily Lloyd and written and directed by David Leland. Terence drifted from job to job and drank heavily every day: ‘Even when there was nothing in the kitty he always found enough for whisky,’ Cynthia later remembered. It wasn’t long before she moved to London, working at Swan and Edgar’s department store on Piccadilly Circus while paying £3 a week for a at in Hammersmith. Terence, without much else to do, followed Cynthia to the capital. Although he only stayed for a few days, Cynthia fell pregnant and eventually gave birth to her son Dominic. The following year, after the result of another a air, a second son was given up for adoption at not more than a few weeks old.

It was around this time that the luncheon voucher started to take off. The scheme initially had worked on an ad hoc basis, with each company printing their own vouchers and arranging for local cafes and restaurants to accept them. In 1954, the businessman John Hack realised that a standardised voucher, acceptable all over the UK, would be much more e cient for everyone concerned and started the Luncheon Voucher Company, based in Saxone House on Regent Street. Establishments that were part of the scheme started to feature a green ‘LV’ logo in the window (as did Cynthia twenty years later). In 1957, an advert for the company boasted that ‘two million vouchers were used every month at more than 4,000 catering establishments in London and the provinces’.

Many of the early voucher schemes seem to have been started by employers who thought their staff, through not getting a proper midday meal, were getting tired and inefficient in the afternoon. In 1961, the Guardian reported that young women in particular were too busy during their lunch hours to eat properly: ‘Too often lunch-hour shopping swallowed whatever time had been set aside to buy food and whether stimulated by business efficiency or philanthropy, firms evolved the voucher system. In this way they were able to subsidise meals without the risk of the subsidy being diverted to other uses.’ In 1963 one Luncheon Voucher advertisement read, ‘“Good Afternoon,” she said – and it was! Thanks to Luncheon Vouchers she’d eaten well that lunch-time. So she was attentive, looked alive, felt active. A good hot lunch had made all the difference between afternoon apathy and afternoon efficiency.’

The Guardian was wrong, however, and the Luncheon Voucher subsidy was often diverted to other uses. The era of rationing had only just come to an end (meat and all food rationing finished in July 1954) so many people were unembarrassed to find a way around the system.

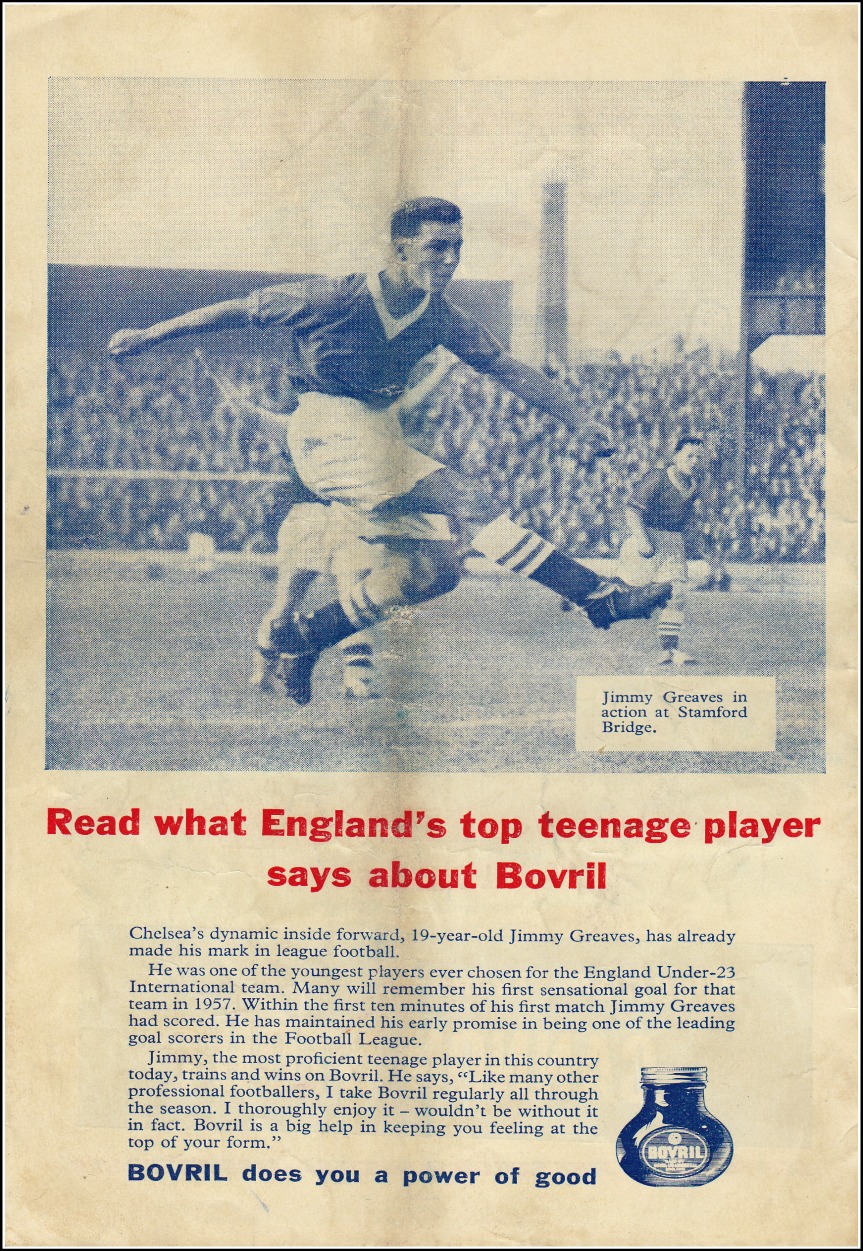

In the summer of 1957, the footballer Jimmy Greaves turned professional at Chelsea (although he spent eight weeks working during June and July at a steel company to supplement his income). His wage was £3 plus £2 for accommodation, which went to his mother because he still lived at home. As he did reasonably well in his exams, one of his duties at Chelsea was to work in the club office for the club secretary, John Battersby, instead of working with the ground staff.

At lunchtime the first-team players went to a ‘posh establishment’ called Anabel’s, a tiny, in-the-know bistro at 356 Fulham Road, while the reserve team and youth players went to Charlie’s, a steamy-windowed cafe where there was one spoon for stirring tea attached to a string on the counter. ‘They served a smashing plate of bacon, eggs, sausages, beans and fried bread,’ Greaves once remembered. ‘It was the sort of daily meal to make Arsene Wenger pale!’

The players were given luncheon vouchers with a face value of 2/6d (12.5p) with which to pay for lunch. It was part of Greaves’s job to issue the vouchers to the rest of the players, but he soon found out that no one really kept a tally on how many were in the office and how many were being issued. It wasn’t long before he realised that the vouchers were valuable ‘black market’ currency.

One of Chelsea’s first-team players, John ‘Snozzel’ Sillett, approached Greaves with a scheme to make ‘a few bob’. ‘I’m not suggesting for one moment that you steal them,’ John told him. ‘Them luncheon vouchers are imprisoned in that office. I want you to help me liberate them.’

Greaves knew that John and his brother Peter, the Chelsea first-team full-back, traded the vouchers down at Charlie’s ‘at less than face value for fags’. John Battersby was a particularly heavy smoker and each morning he would give Greaves some money to buy some Senior Service cigarettes. The Sillett brothers, in return for some of this cash, would then give Jimmy the packets of Senior Service they had bought with the luncheon vouchers liberated from Battersby’s desk drawer. Life at Stamford Bridge in those days, Greaves would later say, ‘was like Harry Lime’s Vienna’.

Most knew that there was a Luncheon Voucher black market and there were often questions asked in the House of Commons. In 1960 Eric Fletcher, the Islington Central MP, asked Derick Heathcoat-Amory, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, whether he was ‘aware that luncheon vouchers, issued by firms and subsequently claimed as tax relief, were frequently being used, not for the purpose of bona fide luncheons, but in exchange for groceries, cigarettes, and other commodities’.

In response the Chancellor admitted that they had seen reports in the press about the misuse of luncheon vouchers but promised to ‘keep the whole question of the taxability of luncheon vouchers under review’. Even by 1960 the three shillings tax relief was seen by many as inadequate. A letter to The Times in August of that year claimed that it was ‘meant to ensure that it would ensure a proper luncheon to young people starting in business or at the lower end of the salaries scale. Three shillings a day now only covers the cost of a couple of sandwiches and a beverage – the very type of luncheon previously scorned by medical experts for the maintenance of health.’

When she was twenty-two, Cynthia Payne met an amusement arcade operator from Margate with whom she lived for five years. After her third traumatic and illegal abortion (the man refused to use contraception), she left him and soon started the career that one day made her famous. Cynthia slipped into prostitution as a way of avoiding eviction from her at when she was falling behind in the rent – ‘I realised I could do “it” and make money at the same time,’ she later said. ‘It made me bloody determined. I was never going to go crawling for money again.’

Cynthia spent two years working as a prostitute before realising she would make more money and have an easier life by opening her own brothel. She saved enough to buy a small terraced house in Eden Court Road in Streatham, and then a few years later, in 1974, bought the house in Ambleside Avenue called ‘Cranmore’.

To hide what was really going on at the house she told her neighbours that she held a lot of lunchtime conferences. This seemed feasible, as most of the cars that clients parked along the road were very expensive. ‘We had a high-class clientele,’ Cynthia remembered years later. ‘No rowdy kids, no yobs, all well-dressed men in suits who knew how to respect a lady. It was like a vicar’s tea party with sex thrown in – a lot of elderly, lonely people drinking sherry.’

She was proud that she provided for all sorts of men, and once said: ‘Everyone can get lonely … We even used to have some of them coming along in wheelchairs, although not too many because they tended to block up the corridors.’ By the mid-seventies, a time of high inflation, Luncheon Vouchers had become even less valuable.

Another letter writer to The Times in 1976 complained of their value (readers of this newspaper seemed particularly careful with their money): ‘I was horrified to find that the maximum untaxed limit on the value of luncheon vouchers imposed by the government of 15p only purchased a plain cheese sandwich. Meat was out of the question. Mr I. E. C Grant of Bookham in Surrey.’

The days of ‘a couple of sandwiches and a beverage’ at lunchtime were already long gone. In 1980, two years after the police raid on Ambleside Avenue, the case went to court, with Payne eventually convicted for running ‘the biggest disorderly house’ in history. Judge David West-Russell noted, however, that Mrs Payne had appeared in court on four previous occasions, on similar charges and not only sent her to jail, he ned her a total of £1,950 and ordered her to pay costs of up to £2,000.

A few days later a Commons motion criticising her imprisonment was signed by thirty MPs of all parties. They included Sam Silkin, a former Labour Attorney General, as well as Tony Benn. If anyone should be jailed, they reasoned, it should be her clients, who, of course, all remained nameless. A cartoon in the press at the time showed a vicar in bed with a prostitute, confronted by a policeman: ‘I demand to see my solicitor,’ said the vicar, ‘who is in the next bedroom.’

Although sentenced to eighteen months in prison, after an appeal she was released from Holloway after four. It was said she was driven away from prison in a Rolls-Royce driven by a former client to take her to a ‘coming-out’ party. Six years later, in 1987, Personal Services, the first film of her life, was released, starring Julie Walters and directed by former Python, Terry Jones.

After the filming was completed, Payne organised a celebration party at Ambleside Avenue, and once again the police raided the house. At first, two plainclothes policemen gained access to the party, with one of them dressed as a woman, and then after a signal thirty more officers burst in to the property. ‘I was not running a bawdy house,’ she endlessly explained over the years,‘I was simply having a party.’

This time she was charged with nine counts of controlling prostitutes. There was much laughter during the subsequent thirteen-day court case, and the judge warned the jurors that it was a criminal trial and not some kind of entertainment show. When, after five hours, the jury found her not guilty, the courtroom burst into spontaneous applause.

Payne left the court clutching a Laughing Policeman doll, which she had kept as a mascot throughout the trial. ‘This is a victory for common sense,’ she said. ‘But I have to admit all this has put me off having parties for a bit.’ Cynthia later sent Judge Brian Pryor QC a copy of her biography, An English Madam, with the inscription: ‘I hope this book will broaden your rather sheltered life.’

No one was writing to the national papers any more about the Luncheon Voucher. They had become next to useless and the LV tax concession, still at 15p after almost sixty years, was abolished by the coalition government in 2013. Luncheon Vouchers do still exist, however, although no one knows who takes them.

Sadly, Cynthia Payne certainly doesn’t, as she died aged eighty-two on 15 November 2015 while still living at Ambleside Avenue. Britain’s most notorious madam was always proud of how she treated her employees, and at the end of every afternoon shift she always provided something of which the glamorous women at Le Chabanais, Salon Kitty and the Mahogany Hall would have been more than envious: a poached egg on toast and a nice cup of tea. ‘I’m not much of a cook, but I do a beautiful poached egg,’ she once said.

This post is an excerpt from Rob Baker’s new book High Buildings, Low Morals due to be published on 15 October 2017. If you’d like a signed copy click on the cover below.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.