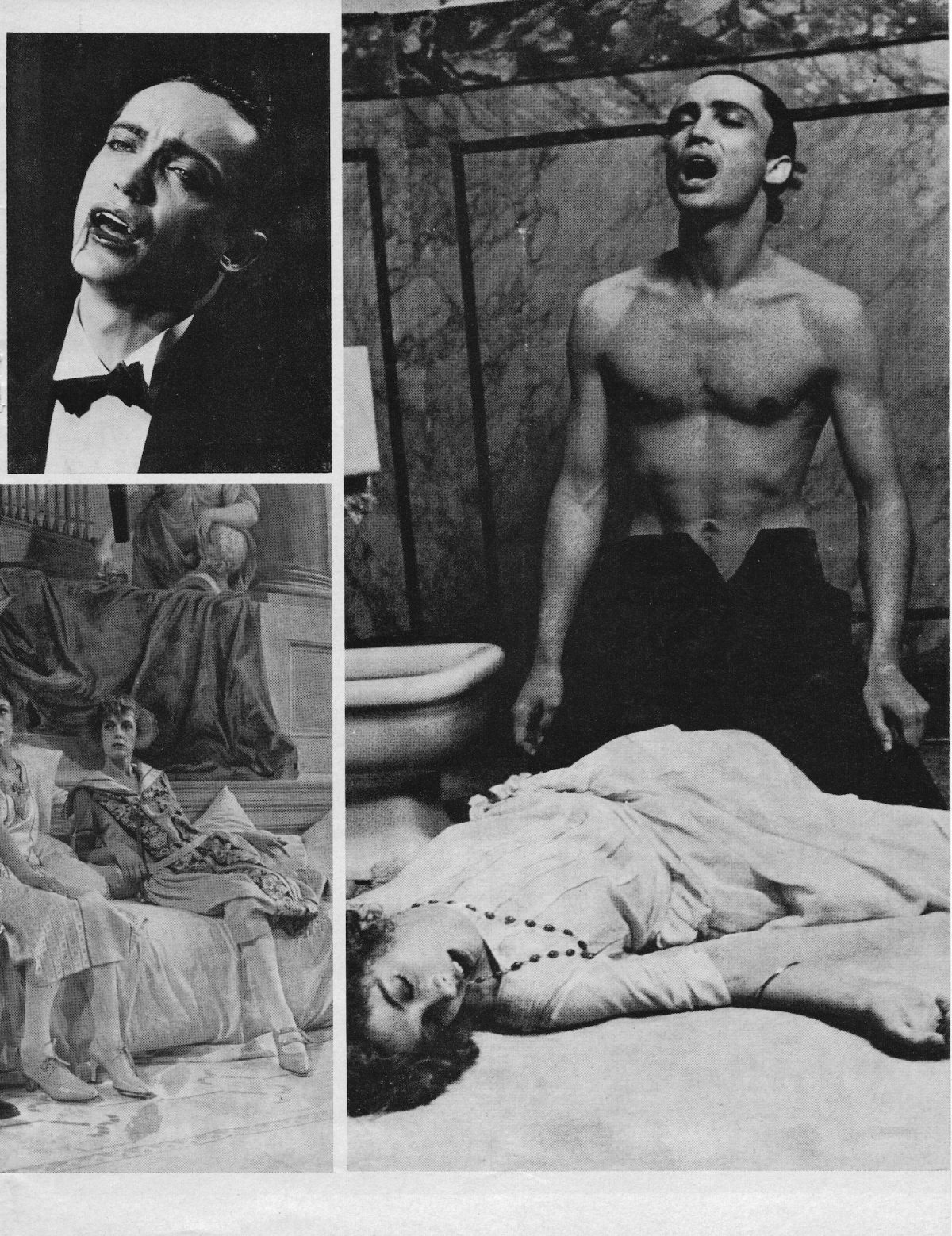

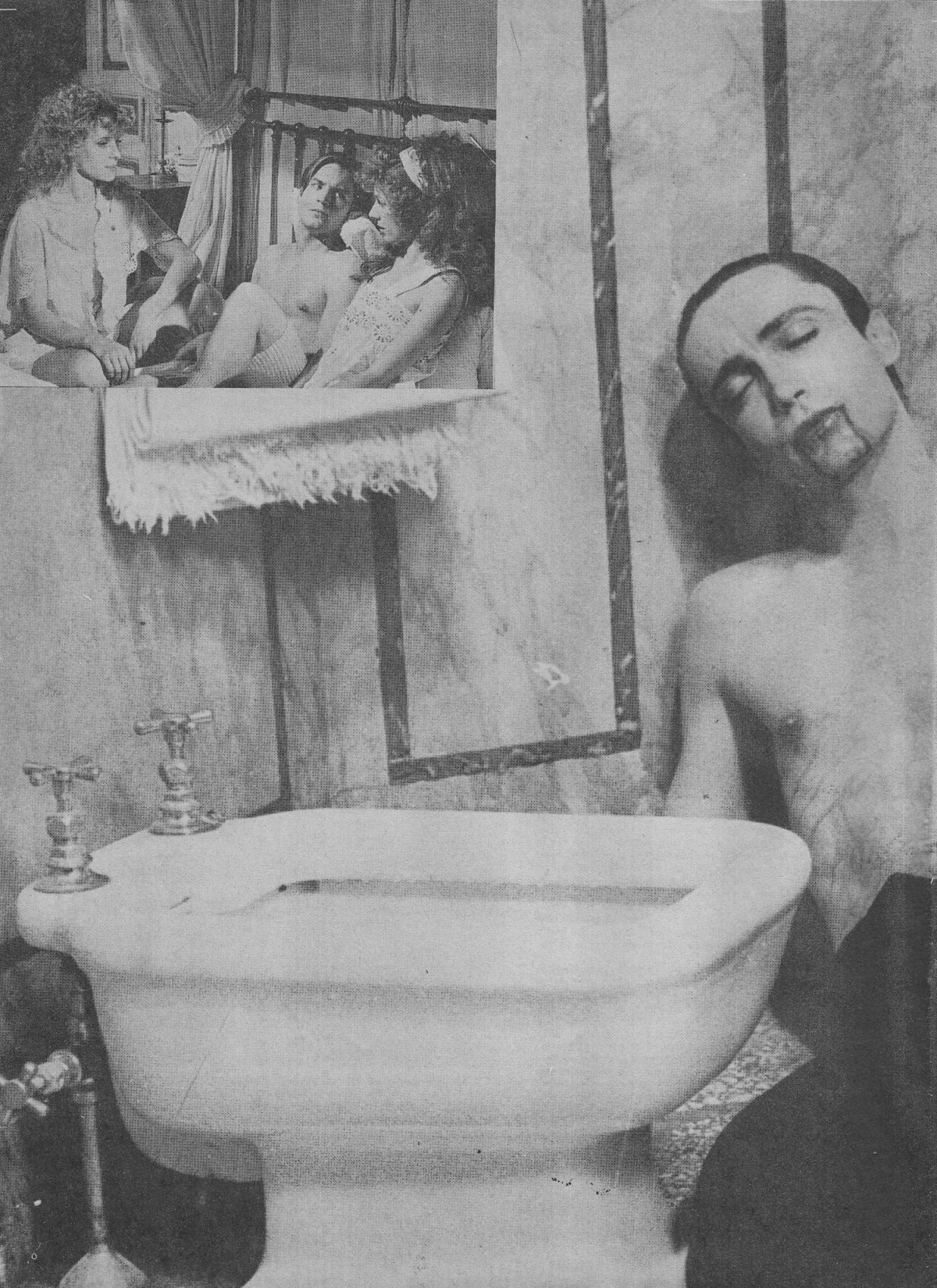

The most beautiful man in the world sits at his dressing table making-up his deathly face. He applies foundation, finger paints his eyebrows, a fist of rouge to his cheekbones, then paints his hair black. As the camera moves away from his face towards the mirror, we see there is no reflection visible.

It’s one of the most original opening title sequences in cinema. Allegedly devised by Andy Warhol, though I presume the director Paul Morrissey would disagree.

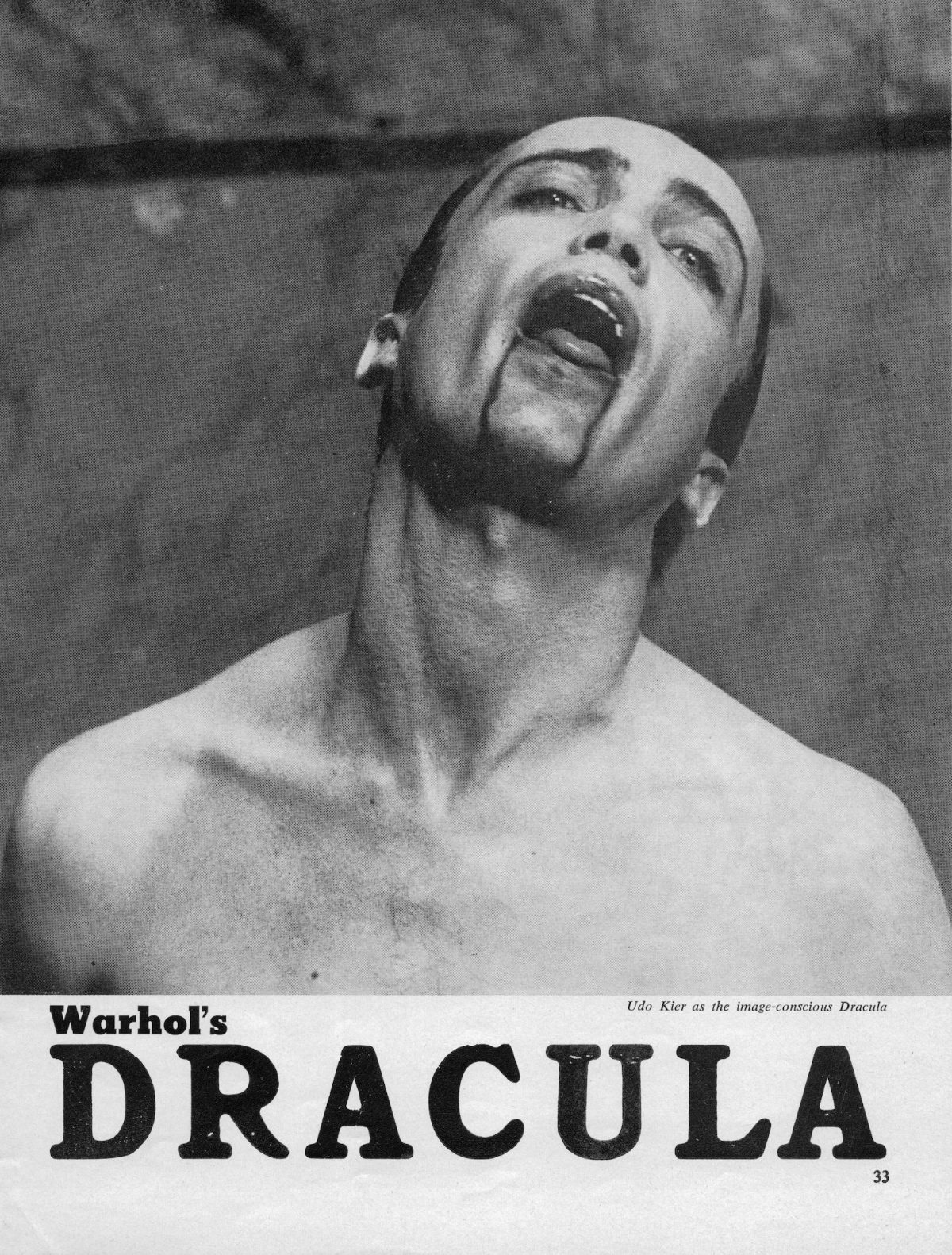

Udo Kier lost ten-kilos to play Dracula. He ate little more than salad leaf and water – “It’s not only Robert De Niro who prepares himself in this way,” Kier later told Dazed and Confused. He became so weak from this lack of food that he had to use a wheelchair, which was became an unintended feature of the movie.

Kier was born in Cologne on 14th October 1944. Not long after his birth, he was recused with his mother from the rubble of the family home after a bombing raid devastated the town.

As a teenager he became friends with Rainer Werner Fassbinder. According to Fassbinder, the pair worked as hustlers in the working class bars of the city. Kier is a tad more diplomatic, claiming they merely sat drinking Coca-Cola “looking at people.”

There was Rita, the first transvestite I’d ever seen. There were truck drivers, and secretaries in glasses. We were only allowed there till 10 o’clock, so, at 10, the owner would scream: ‘Rainer, Udo: out!’

In 1965, Kier moved to England where he hoped to find work as a clerk to help improve his English. One day, while walking down the King’s Road, the most beautiful man in the world soon found himself asked to star in a movie. His film career had begun. Kier starred in a couple of films before gaining considerable praise for his appearance in Mark of the Devil (1970) starring alongside Herbert Lom.

On a flight from Rome to Munich, Kier met Warhol acolyte and film director Paul Morrissey.

I was sitting in an airplane and I was sitting next to a young man with a beard and we started talking and he said, “Hey, what are you doing”, and I said “I am an actor”. This was the beginning of my career. So I showed him a picture of myself. And he said “wow, that’s interesting. Give me your number”.

So he wrote my number on the last page of his American passport. And I said to him and I said, “who are you, what are you doing”. And he said “I am Paul Morrissey, I direct for Andy Warhol” and shortly after that, three months later, I got a call. “Hey, it’s Paul from New York! I’m making Frankenstein for Carlo Ponti and I have a little role for you!” I asked what the role was. He said “Frankenstein”. So, Flesh for Frankenstein was made in 3D.

On the last day of shooting, Morrissey came to me and said, “well I guess we have a German Dracula”. I said “who?” He said “you!”.

Paul Morrissey was an Irish lad from the Bronx. He started out making one-reelers which he showed in an old nickelodeon on East 4th Street. At some point during 1965, Morrissey met Andy Warhol. Both men were making movies. Morrissey offered to help out eventually taking becoming the Factory’s movie director.

In 1968, Warhol was shot by Valerie Solanis. While he recuperated, Morrissey wrote, cast, filmed, directed, edited, and distributed Flesh.

As he told the New York Times in 1973:

Andy had the idea of making films cheap, throw‐aways, you could say. They’re Andy Warhol films, sui generis. Like there are Italian films, Hollywood films, musicals. They got the underground label because when they began, there was no other place to put them. They don’t fit in at all with Jonas Mekas’ idea of cinema as poetry. Andy Warhol.

We’re trying to make movies in a style that’s commensurate with the way people live their lives today. For instance, before the war, there were moral codes, a certain guilty conscience about things, there was more of a form to life itself. Now life is formless, aimless. on the Ed Sullivan show and how they said things.

Morrissey was not interested in having any message in his films. If ever there was the hint of a message it was cut out.

I think it’s absurd to believe that movies should look like paintings and say something, like serious books say something.

After his near fatal shooting, Warhol no longer wanted to direct. Instead, he wanted to produce like Walt Disney.

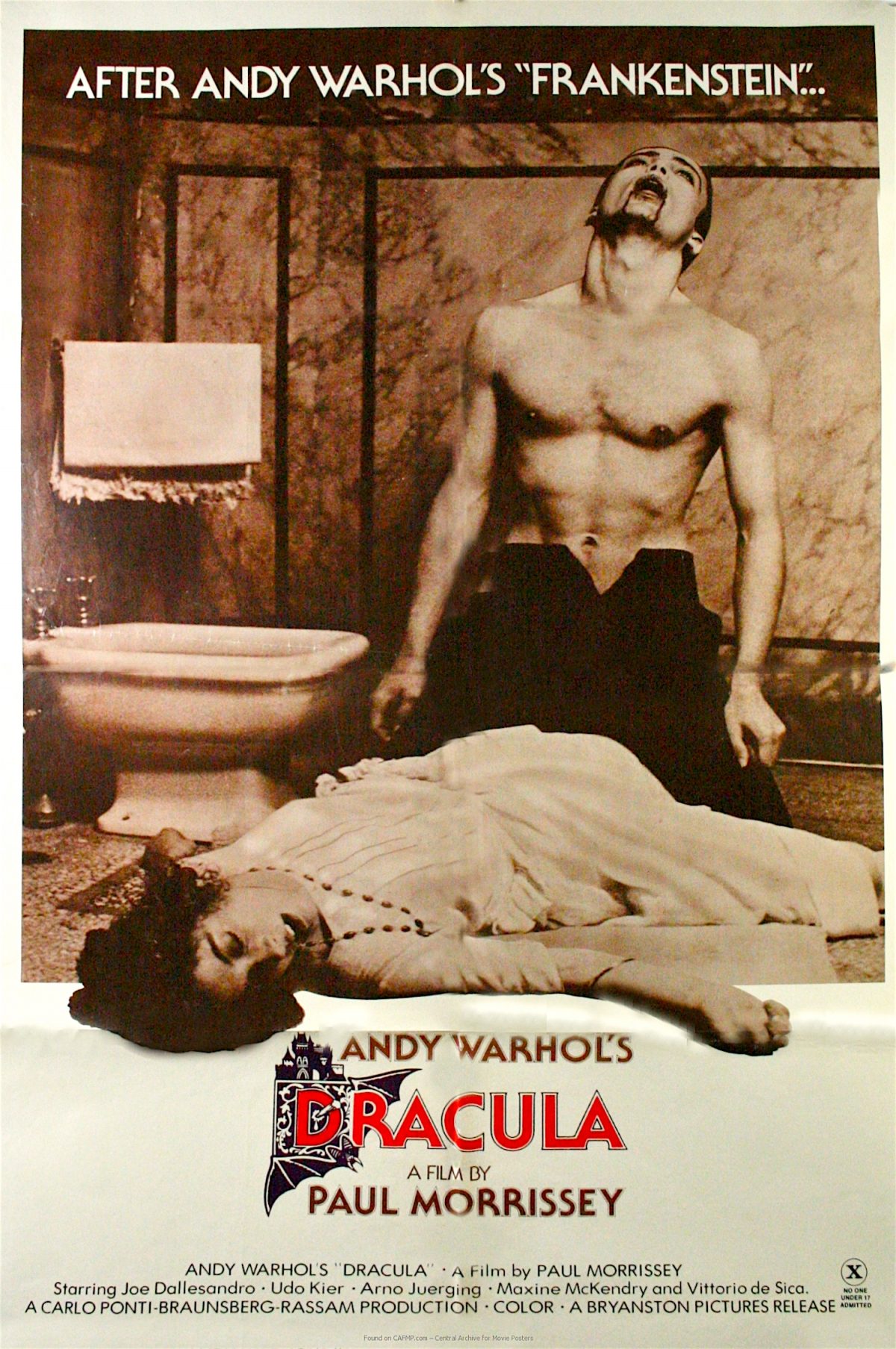

Morrissey agreed a deal with producer Carlo Ponti to make two films in Italy. The first was Flesh for Frankenstein shot in 3-D. The second was Blood for Dracula. Both were directed by Morrissey despite some claims that Antonio Margheriti was the man behind the camera, as Kier explained to Coming Soon:

[W]hy Margheriti is credited on some prints is that there were too many Europeans in the film and by law you had to have a European director on set. I met Antonio before because of his movies in Spain and Italy. Fellini was shooting next door to us.

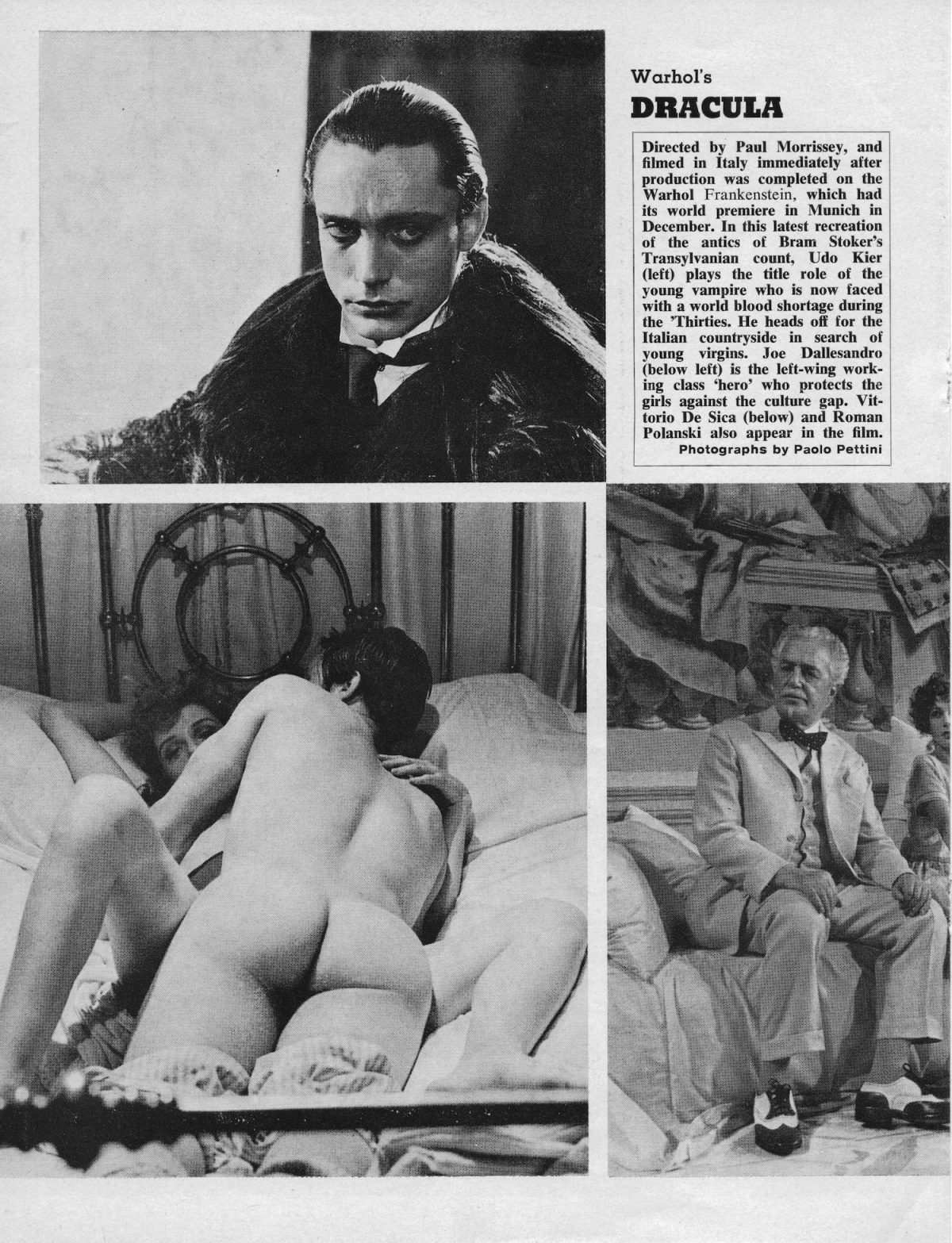

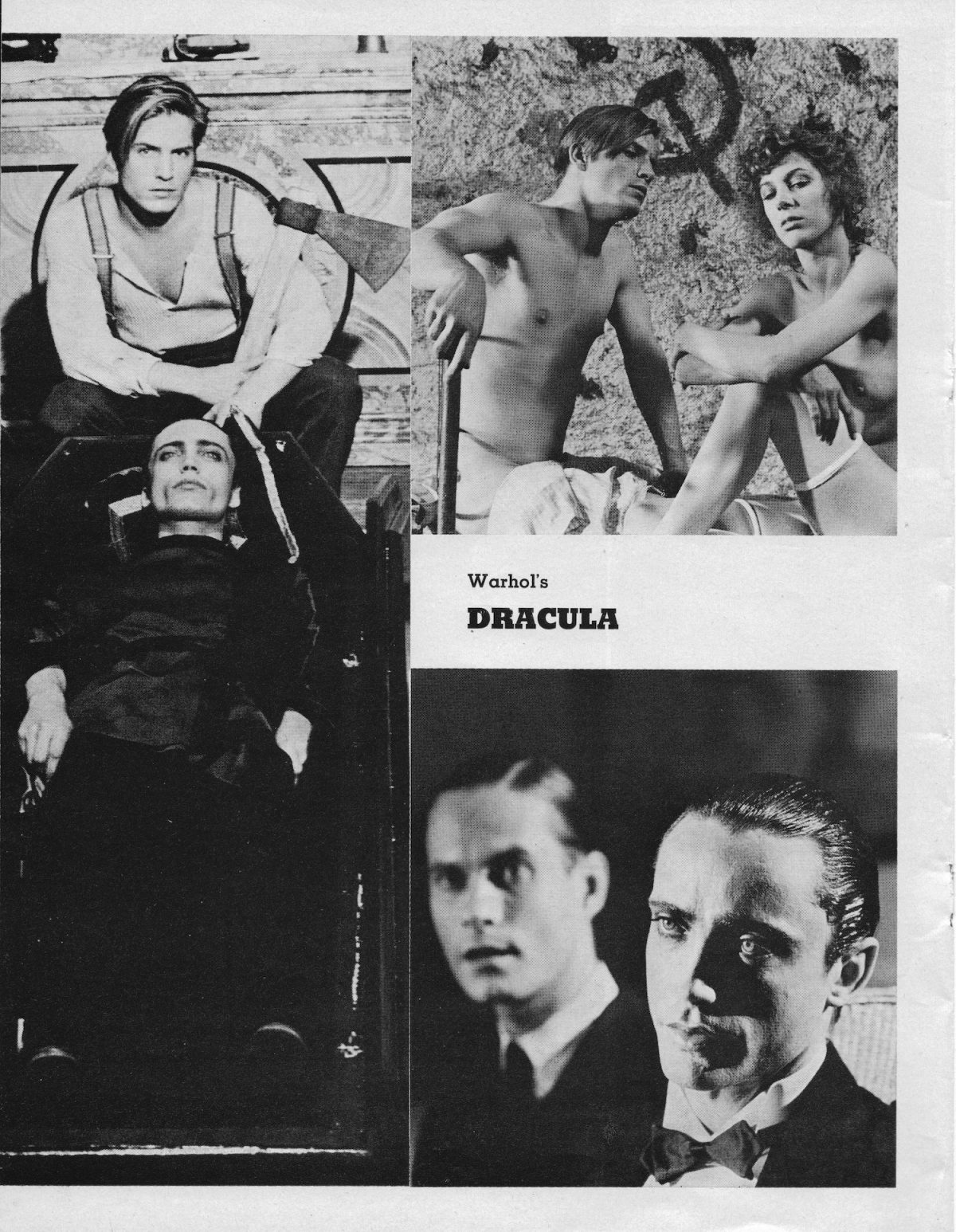

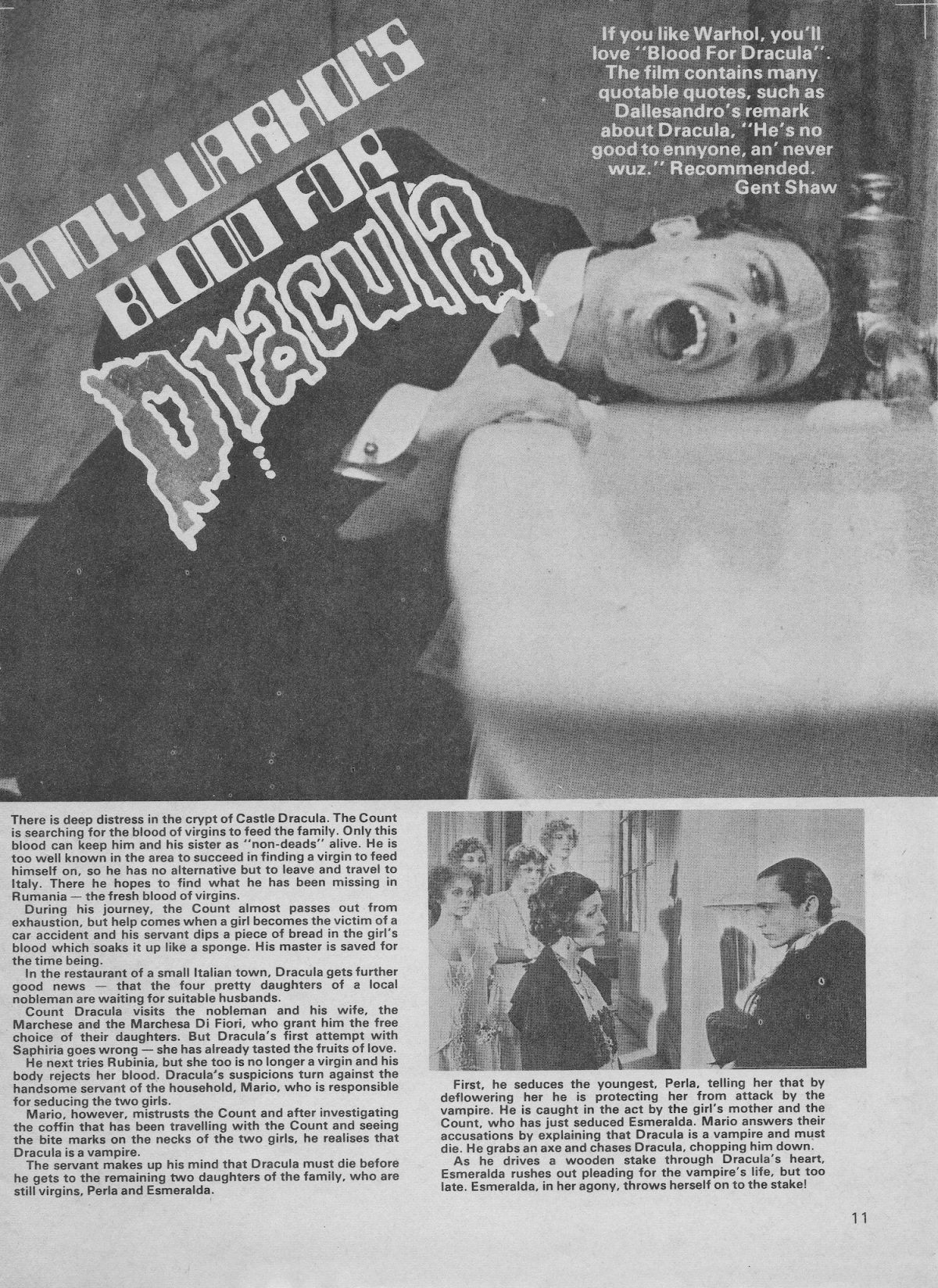

Morrissey’s film cast Dracula as a relic of decadent upper classes soon to be destroyed by the Marx-spouting handyman-cum-peasant (hunky Factory regular Joe Dallesandro) who deflowers all the local “wirgins” deprivng the Count of his needed life-saving virgin blood.

Kier’s performance as Dracula was original and idiosyncratic. He presented the Count as decadent man torn by his addiction while aware of his own ruin. The film contained notable performances by director Vittorio de Sica and a memorable cameo by Roman Polanski.

Despite his performances in Flesh from Frankenstein and Blood for Dracula, Udo Kier was never to receive star billing again. More’s the pity, as Kier is one of most interesting and compelling actors working today.

The following pages come from Films and Filming and World of Horror.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.