Careers like that of photographer Art Kane seem like exactly what the phrase “strength to strength” was meant to describe. In 1958, Kane “assembled the greatest legends in jazz and shot what became one of his most famous images,” notes the Morrison Hotel Gallery. That photo, A Great Day in Harlem, ended up becoming one of the most iconic music photos of all time, enough to cement Kane’s name in the histories of jazz and photography. He then went on, in the 60s and 70s, to photograph “among others, the Rolling Stones, the Who, Janis Joplin, the Doors, Aretha Franklin and Bob Dylan.”

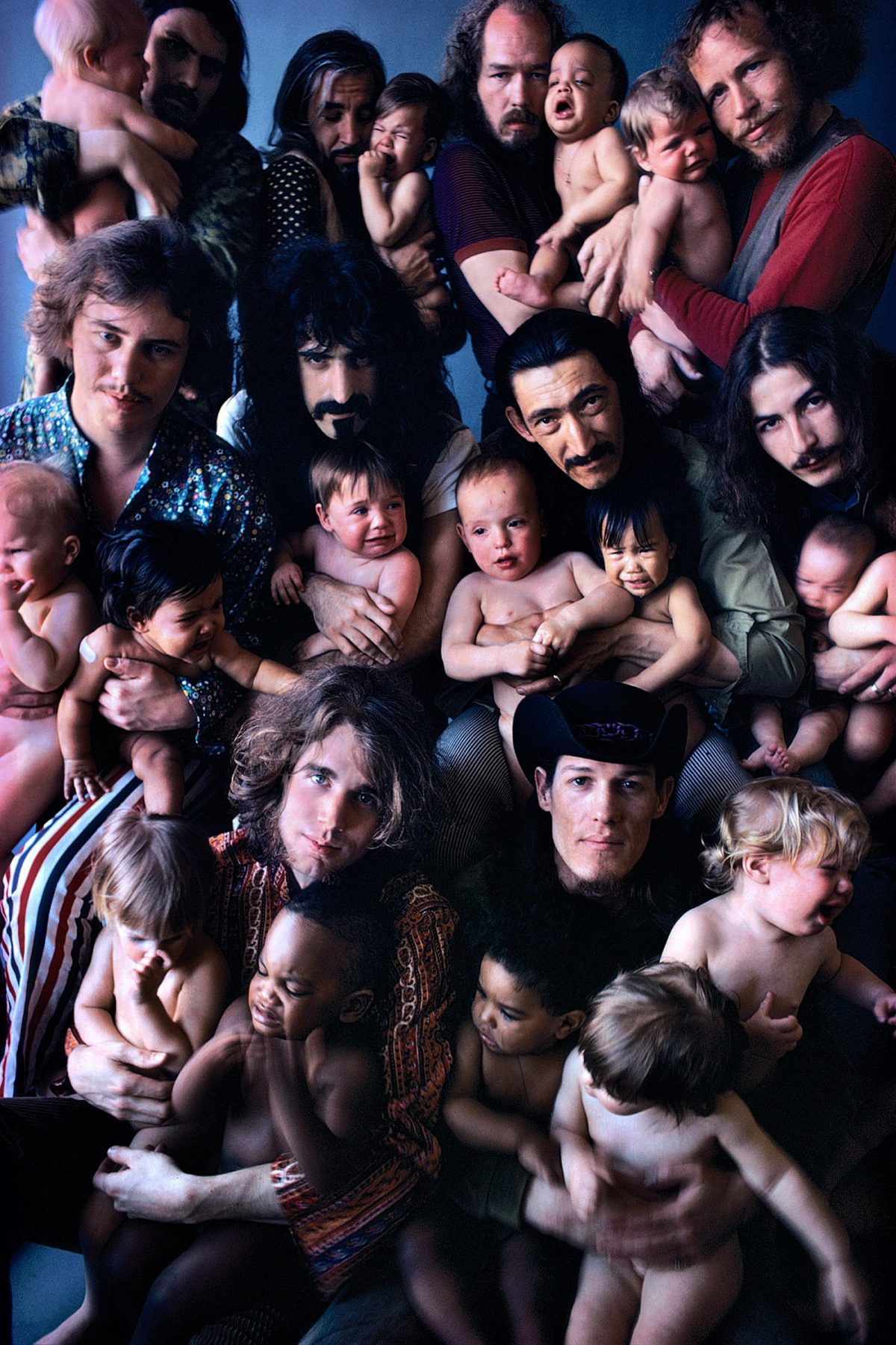

The “others” include Cream, Jefferson Airplane, Sonny and Cher, Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, and Andy Warhol, painted gold. Kane began his career as an art director for Esquire and Seventeen but wanted to move out of the role and take his own photos. A Great Day in Harlem was his first freelance assignment for Esquire and it launched his new career, one characterized by innovations that would define music and fashion photography in the coming decades.

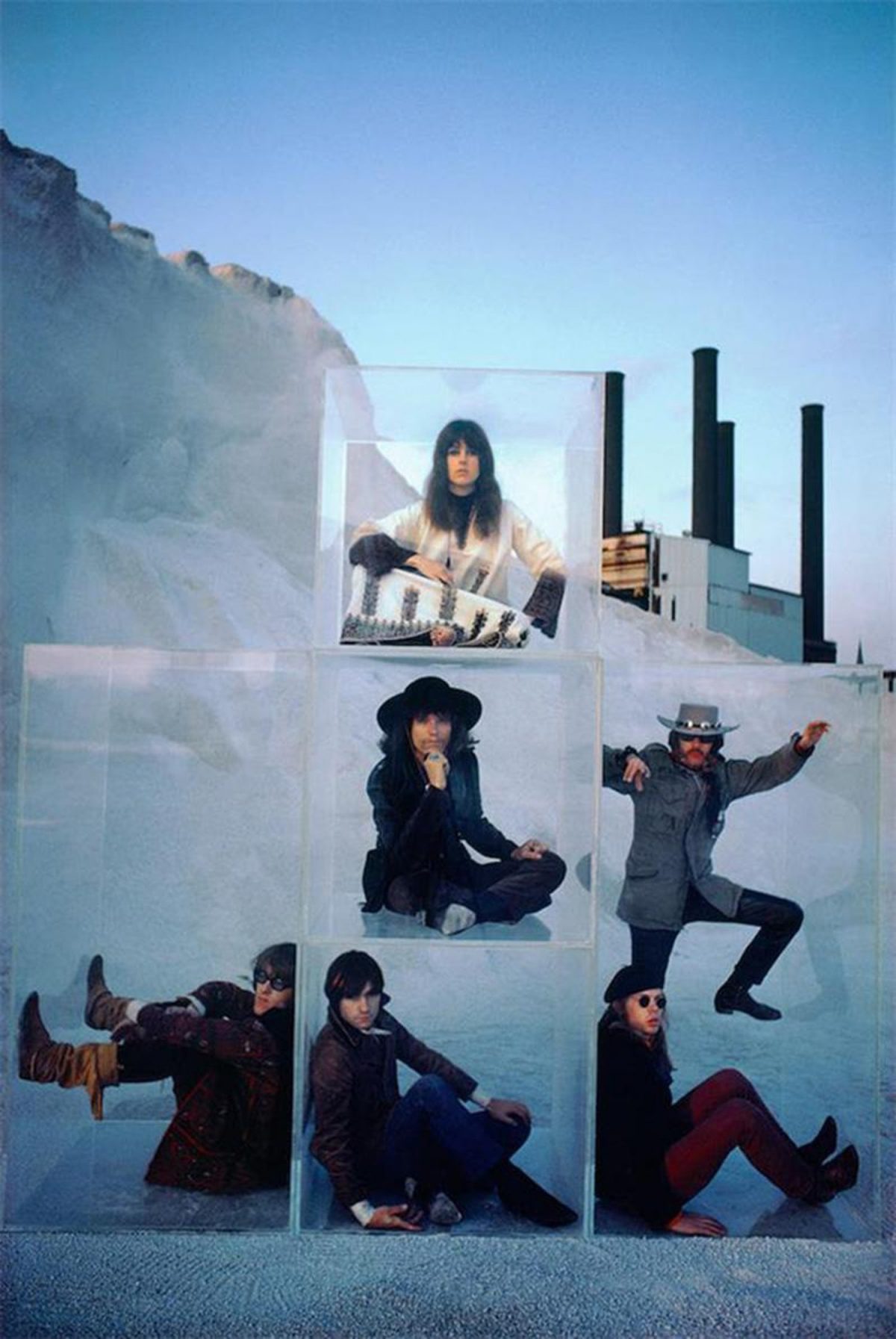

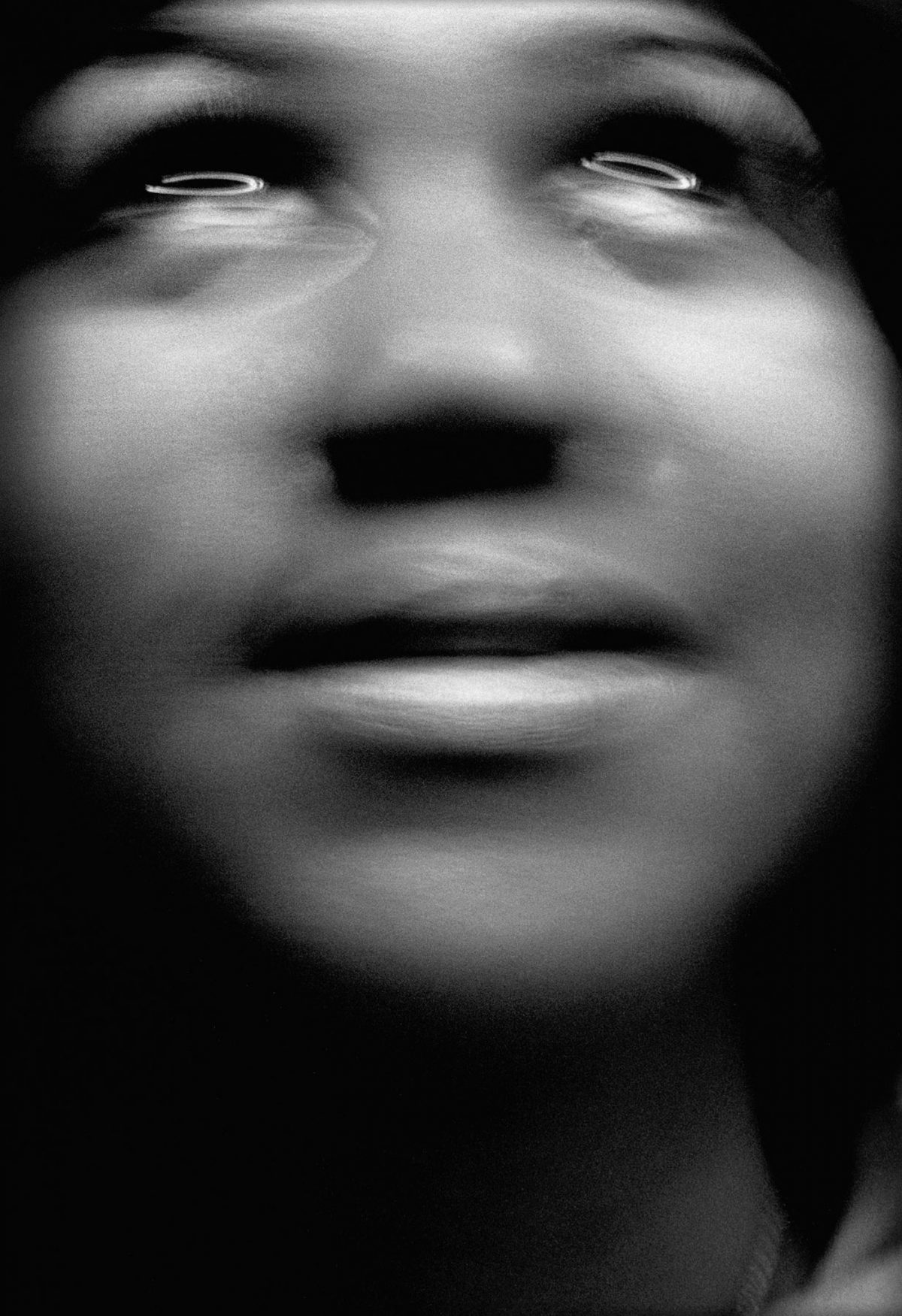

Thirty years before Photoshop and digital imaging, armed only with a light table and a loupe, Kane invented the ‘sandwich’ image; two, four, and more transparencies layered, inverted, reversed, book-matched, painstakingly aligned, and taped together at the edges. In perfecting this technique, Kane pioneered photographic storytelling by investing his images with metaphor and poetry, effectively turning photography into illustration.

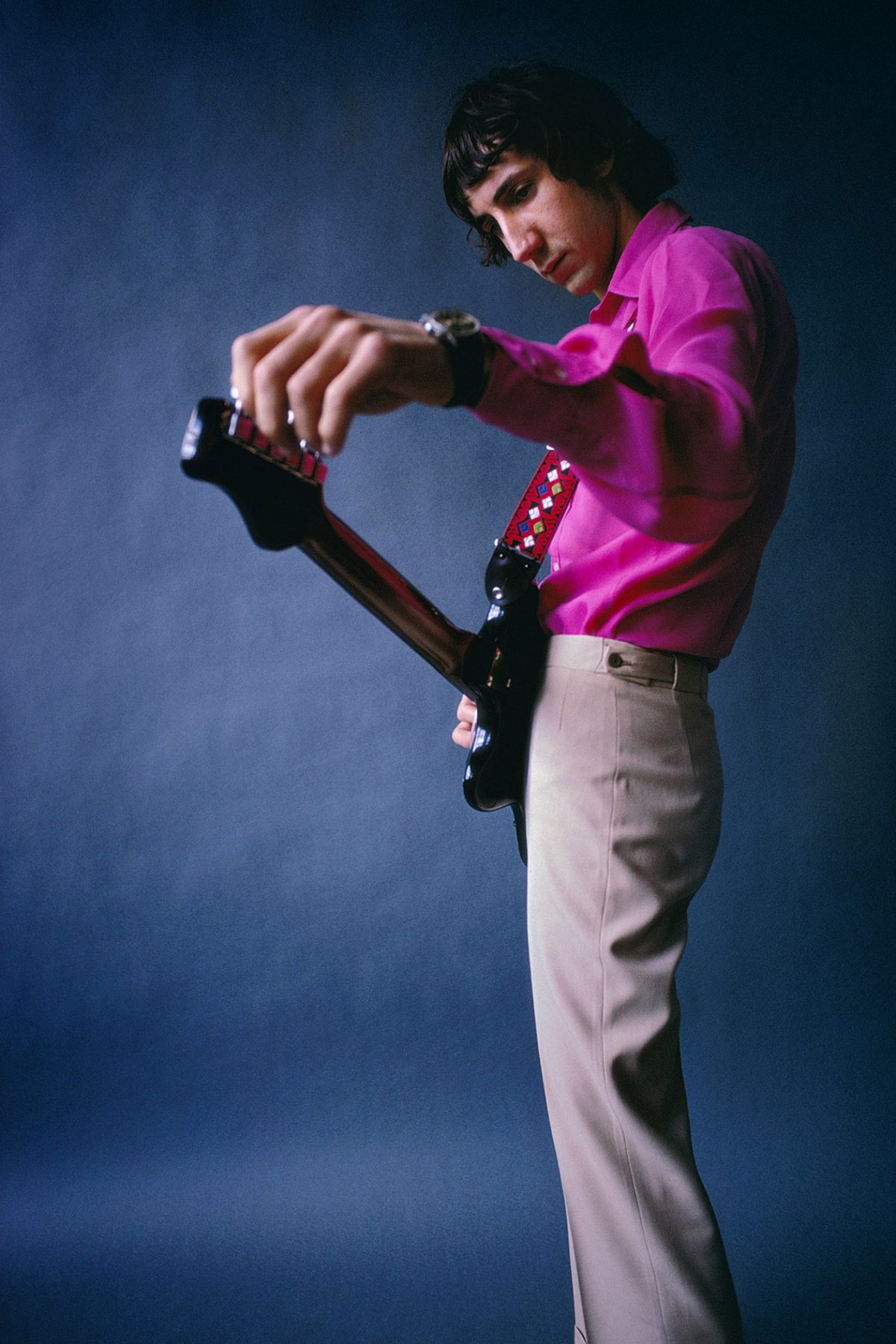

Unlike many a rock photographer who hovers on the edges, waiting for the right moment to take the shot, Kane carefully staged and managed his photo setups. “You have to own people,” he said of his celebrity portraits, “grab them, twist them into what you want to say about them.” This technique didn’t quite work with the 57 jazz legends (and assorted neighborhood kids). “After a couple of hours” spent “trying to control the chaos,” writes Natasha Desai, he threw up his hands “and soon things fell into place.”

When it came to photographing the Who in what became a series of signature shots of the band draped in the Union Jack, Kane was able to exercise the kind of control he liked to have over his subjects. “When Art Kane took our picture,” Pete Townshend remembers, “he told us, ‘Go there, do this, do that, be asleep, put your head on his shoulder.’” The approach produced editorial images that defined a generation of musicians as larger-than-life characters.

None of Kane’s careful setups were decided on a whim—the photographer staged each picture with a studied eye toward how he came to see the artists after spending significant time in their world. “Prepping for a shoot was an extensive process for him,” Desai writes. “Kane would immerse himself in their music for days on end while visualizing and sketching their shots.” Like a cinematic auteur, “he would eventually produce images that were almost exactly what he had envisioned.” He couldn’t make Sonny and Cher look cool, but he made himself look pretty badass seated behind Keith Moon’s drums.

The process didn’t always go as planned, of course. When it came to those portraits of the Who, Kane began shooting in the studio, then moved outside “when he felt that the studio shots looked far too sterile.” (Just as in A Great Day in Harlem, the kids wandered into the Who shoot spontaneously.) He preferred natural light, and despite his reputation for dictatorial control over his shoots, he remarked, “as a photographer, I’m not observing too carefully where I’m going, because tripping over a stone might just lead to something marvelous…. I hate to feel that I know exactly what’s going to happen.”

Kane somehow found just the right balance of preparation and improvisation, giving his photos a compositionally formal quality that still hold surprises decades later. But “while the world looked on with wonder,” Kane saw himself as just another “poor bastard for whom the real world just doesn’t look good enough.”

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.