In a fascinating book originally put together by Hunter Davies in the late sixties called The London Spy – A Discrete Guide To The City’s Pleasures, and first published in 1966, there are two chapters written specifically for gay and lesbian visitors to London.

The first, entitled ‘Men For Men’, notes around twenty venues where men could meet ‘soul or bed-mates and/or escape the attentions of the fat girls with whom you flew over on your chartered 747′. One of these clubs, under the sub-title of ‘non-dancing clubs’ was called Gigolo at 328 King’s Road (now a carpet shop) and was described by the book as an “Aptly named, hot, incredibly packed coffee bar. A frotteur’s delight. Lots of Spanish waiters and terrified Americans. The Rolls-Royce outside could be the one to whisk you away from it all.”

In the second chapter called ‘Women for Women’ and written by the novelist Maureen Duffy, there is mention of just one venue – the famous Gateways Club.

The Gateways had been in existence at 239 Kings Road on the corner of Bramerton Street in Chelsea since the thirties. It became more or less exclusively lesbian during the war when a huge number of women came to London to work or were stationed nearby and needed somewhere to go they could call their own.

A man called Ted Ware took over the club during the war, purportedly winning it in a poker game (“I raise you my lesbian members-only club…”). He married an actress called Gina Cerrato in 1953 and she soon took over the running of the club, joined, after a few years, by an American woman called Smithy who originally came to England as a member of the American Airforce. After an arranged marriage in the early sixties Smithy stayed in London for the rest of her life.

The membership fee during the sixties was just ten shillings (50p) and no guests were admitted after ten o’clock to discourage people who had spent their money elsewhere. Maureen Duffy explained that ‘rowdies or troublemakers’ were often banned immediately. Being excluded in those days was more than just embarrassing, it was unbelievably inconvenient – the nearest alternative lesbian club would have been in Brighton. Dining out with a girlfriend was often too expensive for a lot of women and even into the sixties women wearing trousers were actually banned from many restaurants. Pubs were, on the whole, unpleasant places for women especially if unaccompanied by a man. In 1969 the London Spy guide book’s main advice for women looking for a drink was, essentially, to avoid pubs if they were alone, saying;

You may be thirsty, but nobody, nobody will believe you.

So for many women, especially if you preferred the company of other women, the Gateways Club was the only relaxing and affordable place you had to go.

After entering a dull green door on Bramerton Street there was a steep set of steps leading down to the cloakroom (looked after usually by Gina) and the entrance to the club. The smokey windowless cellar-like room was only 35ft long and featured a bar at one end ‘manned’ usually by Smithy. Entertainment was a fruit-machine by a pillar in the centre and a jukebox opposite the bar. It was never known whether Gina and Smithy were a couple (Ted eventually died in 1979) but many suspected they were.

During the eighties the club became quieter probably because other lesbian and gay venues were opening in London, and eventually Gateways only opened at weekends. The local neighbourhood in Chelsea was also becoming more and more upmarket and the club lost its late-licence in 1985 due to complaints about loud music. Not long afterwards the famous green door was subsequently closed for ever.

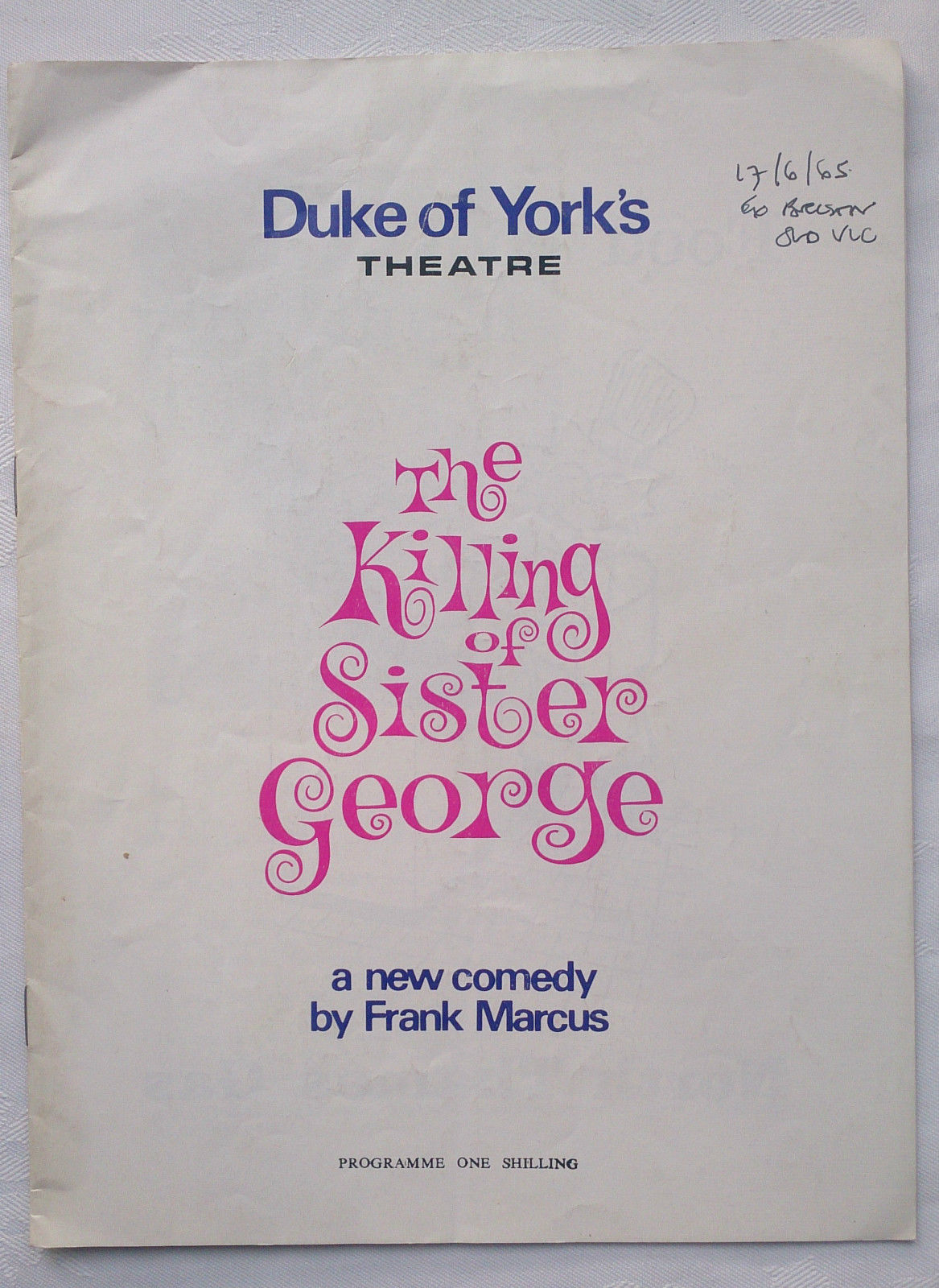

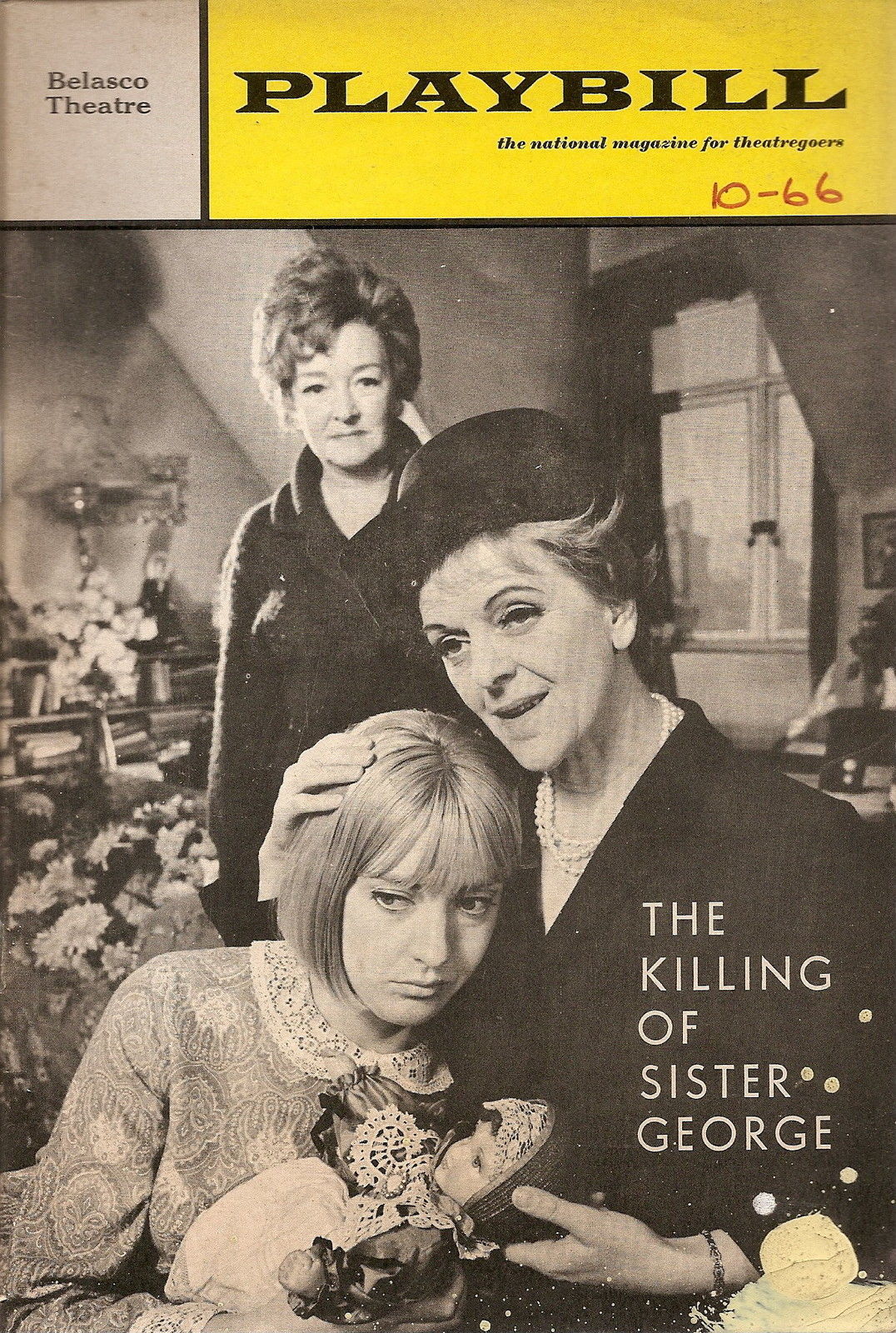

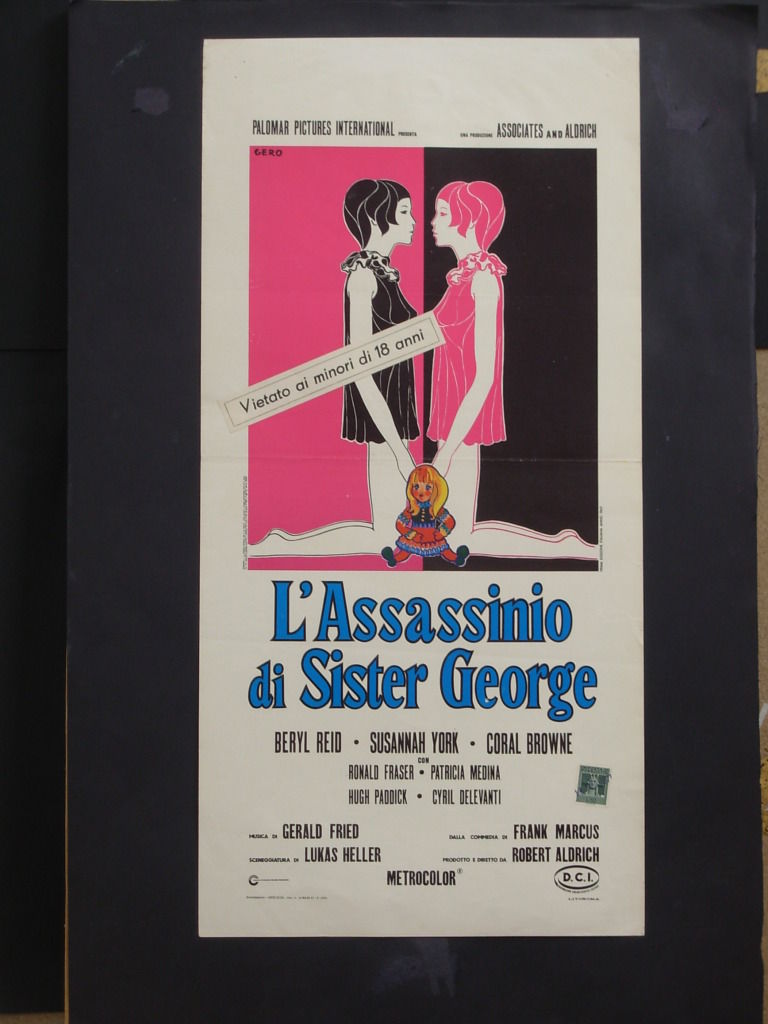

Between the 9th and 16th of June in 1968 The Gateways club became internationally famous when it appeared as a backdrop to many scenes filmed for The Killing Of Sister George, a movie starring Beryl Reid, Coral Browne and Susannah York. In 1960, York, a starlet at the beginning of her acting career and newly married, lived in a house at World’s End in Chelsea just a few hundred yards from the Gateways.

Robert Aldrich, the director, whose previous film was the slightly more macho The Dirty Dozen, decided to include actual customers rather than extras when they filmed scenes in the club. Gina, Smithy and the regulars (who were paid £10 each for the days filming) performed stiffly and uncomfortably in front of the camera but when the film was released, for a lot of people, this was the first glimpse of a hidden lesbian sub-culture they had ever seen.

Beryl Reid who had already appeared in the play at the Old Vic would later say:

Yet when I did the film and Robert Aldrich took me to the Gateways, the club in Bremerton Street, Chelsea, I nearly had a fit. I said, ‘If I’d been here before I did the play, I’d never had done it.’ I didn’t realise they held each other’s bums and went to the gents’ loo. What did they do in the gents’ loo? And Archie, the chucker-out with all the tattoos on her arms! But she was lovely.

Reid, when shown the script for the film, also baulked at the sex scenes (the original play had none, in fact when Robert Aldrich first went to see the play he didn’t realise it was about lesbians at all) and said;

They had me in bed making love to the girl…close like baked beans…I said ‘No, not on your nelly – or maybe her nelly’. I just could not do it. The thought made me sick. It may be silly, but that sort of physical contact, starkers, with another woman frightened me to death.

19th June 1965: Actress Beryl Reid learning to smoke a cigar for her role in ‘The Killing of Sister George’. (Photo by Victor Blackman/Express/Getty Images)

Robert Aldrich once said that Susannah York had a problem with sex scene with Coral Browne and was a ‘bitch to her’. However Jill Gardiner, author of From the Closet to the Screen, Women at the Gateways Club 1945-1985, disagreed and wrote to me about Reid’s and Susannah York’s attitude to the filming:

As I have met and interviewed Susannah York, I would like to defend her from the critical comment above. Susannah simply was not keen on doing any sex scenes at that time, with a lot of male cameramen watching. It wasn’t the fact that the sex scene was with a woman that phased her, she said she would have felt the same if it had been a scene with a man. I think it was the first sex scene she had been asked to do, at a period when these scenes were often viewed as pornographic. Susannah was generous in taking plenty of time to speak to lesbian and gay interviewers, and to the gay press, even before it was at all fashionable for celebrities to do that, and the Gateways girls told me that both she and Beryl Reid were really friendly to them, choosing to spend breaks from filming asking them about their lives.

Susannah York Lobby Card of Killing of Sister George

French poster

29th October 1968: British actress Susannah York plays Alice ‘Childie’ McNaught in the film ‘The Killing of Sister George’, directed by Robert Aldrich. (Photo by Harry Benson/Express/Getty Images)

The Killing of Sister George can’t be said to be exactly a ‘positive’ view of lesbianism and indeed a critic at the time it was released, suggested that the film ‘dealt with lesbians entirely through the eyes of heterosexual males’ while Jack Babuscio in a Gay News review from the 1970s said that the film ‘presents the lesbian world as a grotesque collection of the sick and the predatory’.

However Sister George was a groundbreaking film in many ways and despite the somewhat cliched dialogue, the movie only condemned or criticised the various characters’ foibles and hypocrisies and not really their sexuality. Aldrich said of the character played by Beryl Reid;

Sister George’s loud behavior and individuality . . . are encompassed in her personality, they’re not a product of her lesbianism. . . . She didn’t give a shit about the BBC or the public’s acceptance of her relationships.

The scenes Aldrich filmed at The Gateways were actually notable for their lack of sensationalism (unlike other films at the time trying to cover similar subject matters) and showed the regulars dancing, drinking and flirting just like any other londoners in any other London club.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.