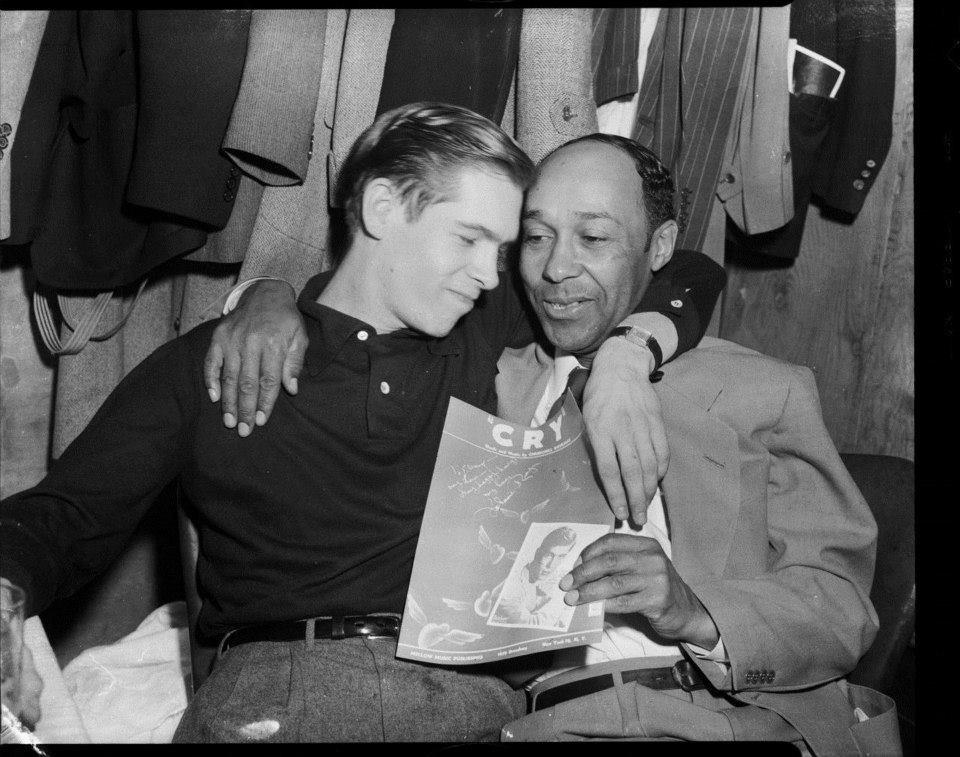

Judy Garland and Johnnie Ray in 1969

At the Register Office in the Chelsea Old Town Hall on the King’s Road, Judy Garland, wearing a blue mini dress featuring ostrich feather sleeves, married a gay ex-discotheque manager and part-time jazz pianist called Mickey Devinko, better known to his friends and associates as Mickey Deans. After the brief marriage ceremony, held at midday on 15 March 1969, and which was actually the forty-six-year-old’s fifth, the reception was held at Quaglino’s, the large and expensive restaurant opened forty years previously in 1929 and situated in Bury Street just south of Piccadilly. Despite the long celebrity guest list none of Judy’s famous friends decided to turn up. Even her daughter Liza Minnelli, who had turned twenty-three just three days before, had called her mother to say, ‘I can’t make it Mamma but I promise I’ll come to your next one!’

The large formal room hired for the reception was a mistake and only accentuated the lack of guests. Glasses of champagne remained un-drunk and most of an ostentatious three-tiered cake stayed uneaten.

It’s not strictly true that there were none of Judy’s celebrity friends at the wedding: Mickey Deans’ best man was Johnnie Ray, the American singer, famous for his ability to cry on stage and who had had several big hits in the UK, including ‘Such a Night’ and ‘Just Walkin’ in the Rain’. Ray had recently been touring the country and in four days he was due to perform with Judy on a Scandinavian tour that Deans had organised, anxious to make his new wife some money. Deans and Garland was severely in debt and when she returned to London at the end of 1968 some newspapers reported that she was immediately served with a writ from Harrods, who said that she owed them £145 15s 2d, a bill outstanding from October 1964.

Micky Deans, Judy Garland and Johnnie Ray

Johnnie Ray at the wedding by Allan Warren

A few weeks before the wedding, on the evening of 19 January 1969, Garland appeared on ATV’s popular The London Palladium Show. No one knew but it was to be the American star’s last ever performance on television anywhere in the world, and it went wrong from the very start. Garland was introduced by the compère Jimmy Tarbuck but the orchestra had to play for two very long minutes before she appeared on stage. Richard Stott in the Daily Mirror wrote:

Singer Judy Garland appeared to be ill last night … Towards the end of the act 46-year-old Judy, who is starring at the Talk of the Town in the West End of London, seemed to have trouble pronouncing the words of towns in a song about Britain. She bent down and asked the orchestra conductor how the words of the song went! At the end of the spot, she threw her arms round Tarbuck and he helped her on to the Palladium ‘roundabout’.

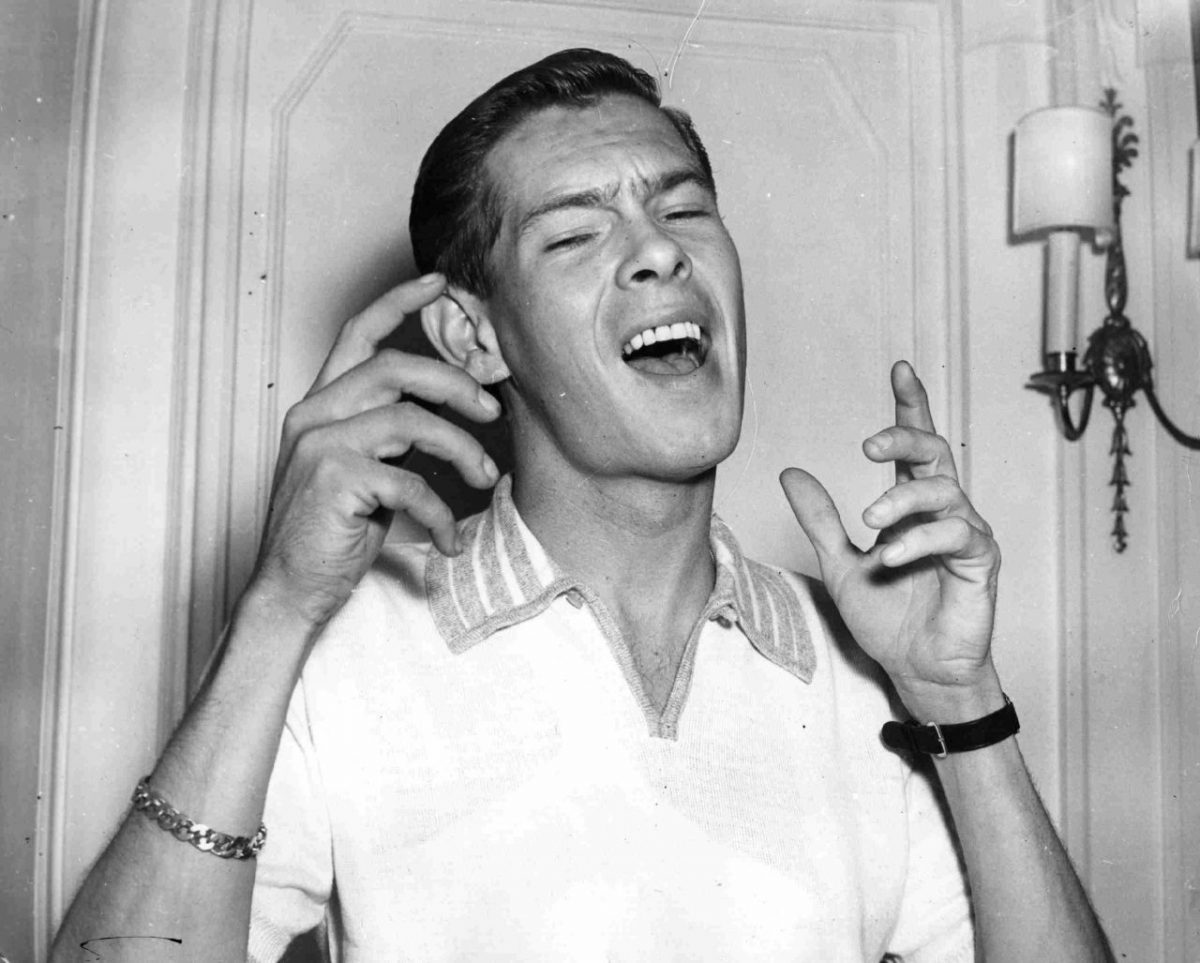

A spokesman from ATV said the next day: ‘She has been suffering from an attack of the flu.’ Two days later, and still complaining of feeling unwell, Garland was welcomed up on stage by Johnnie Ray, who that night was top of the bill at Caesar’s Palace. Alas it was not the famous Las Vegas casino but a cabaret/nightclub (sometimes spelt C’esars) situated 20 miles or so from central London in Luton, not far from junction 11 of the M1. Johnnie Ray these days is known mostly for his nicknames, such as ‘the Nabob of Sob’ and the ‘Prince of Wails’, the frail, almost emaciated, partly deaf American singer was still a relatively big star in Britain in 1969.

Bob Stanley in his history of British pop music Yeah, Yeah, Yeah describes the Oregon-born singer as ‘arguably the most significant modern pop forbear’, and during most of the 1950s Johnnie Ray was huge. Eight or nine years before the Beatles achieved anything similar, Ray was the first star in Britain to make girls in the audience feel the need to scream continually throughout the concert (this can be heard on his 1954 album Live at the London Palladium). In September 1955 London’s Evening Standard wrote that for the first time since London Airport (renamed Heathrow twelve years later in 1967) was opened just after the war, crash barriers had to be installed outside the arrivals hall to keep back the ‘teenage Johnnie fans’.

The newspaper reported that girls were ‘screaming, sobbing, waving their arms and they pressed against the barriers as the singer, wearing his deaf-aid, a sports coat and open-necked shirt, was escorted from the Stratocruiser by a police superintendent’. On the same flight an utterly confused Australian minister for External Affairs, who had seen nothing like it, asked, ‘Who is this entertainer?’ Four years later, in 1959, the Guardian was still reporting that Ray’s ‘emotional impact on his predominantly girlish audience was staggering’ and that ‘amorous contortions with the microphone brought forth shrieks of delight and thunderous clapping and stamping’. His fans weren’t just girls Bob Dylan once said that Johnnie Ray was “the first singer whose voice and style I totally fell in love with.”

An article called The Relevation of Johnnie Ray by Jonathan Poletti discusses his anomalous success:

His live shows became, briefly, unmissable. In her memoir, Rosemary Clooney recalls catching one at the Copa. “Frankie Laine was there, Tallullah Bankhead, the Dutchess of Windsor.” She notes Marlene Dietrich and Yul Brynner there, separately, though everyone knows they’re having an affair. Johnnie sang, Clooney writes, “and everyone waited for him to fall down on his knees and cry and do all the outlandish things that people had never seen done on the Copa stage before.”

Dietrich, I notice, is quoted in a Leonard Lyons showbiz column speaking of the show, saying she approves of the ‘exaggerated mannerisms’. “There’s too much underplaying in show business today,” she says.

The famous deaf-aid was needed, according to Ray, because at age 13, at a swimming hole, he was with a group of boys, throwing each other in the air. He was up ten feet in the air, and coming down, fell on the grass. A blade of grass jammed into his left ear, punctured his ear drum and he lost half his hearing. Disoriented, he walked home. It has been written since that his deafness was congenital and that he was embarrassed by the disability. Cheryl Herr in an academic paper “as though to accept the diagnosis of a severe hearing impairment were deeply embarrassing and painfully dishonoring to his family.”

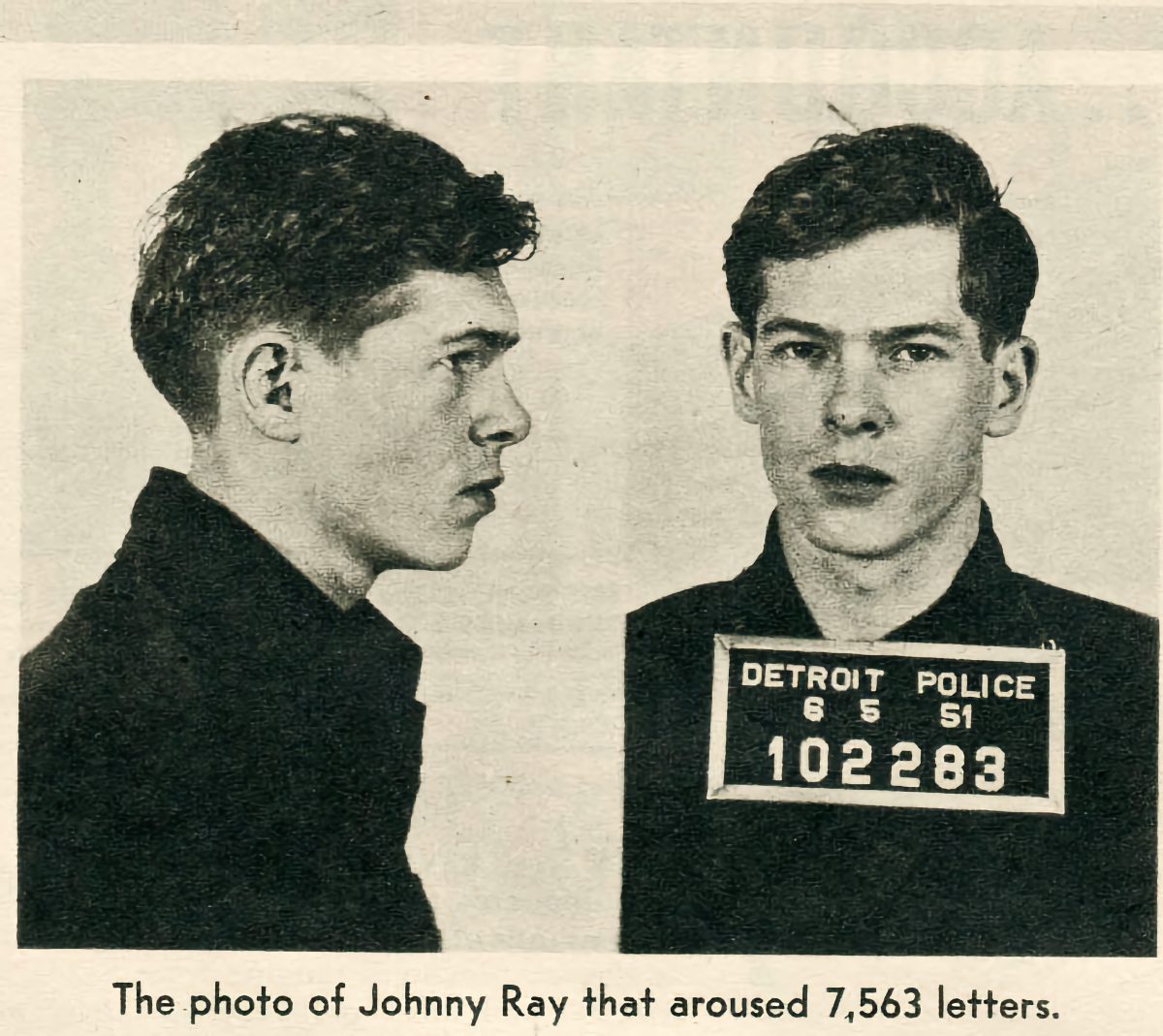

Johnnie Ray mugshot – he was arrested in Detroit in 1951, before his fame for accosting and soliciting an undercover male vice-squad police officer for sex in the restroom of the Stone Theatre, a burlesque house. When he appeared in court, he pleaded guilty to the charges, paid a fine, and was released. Due to his obscurity at the time the press didn’t follow up the story.

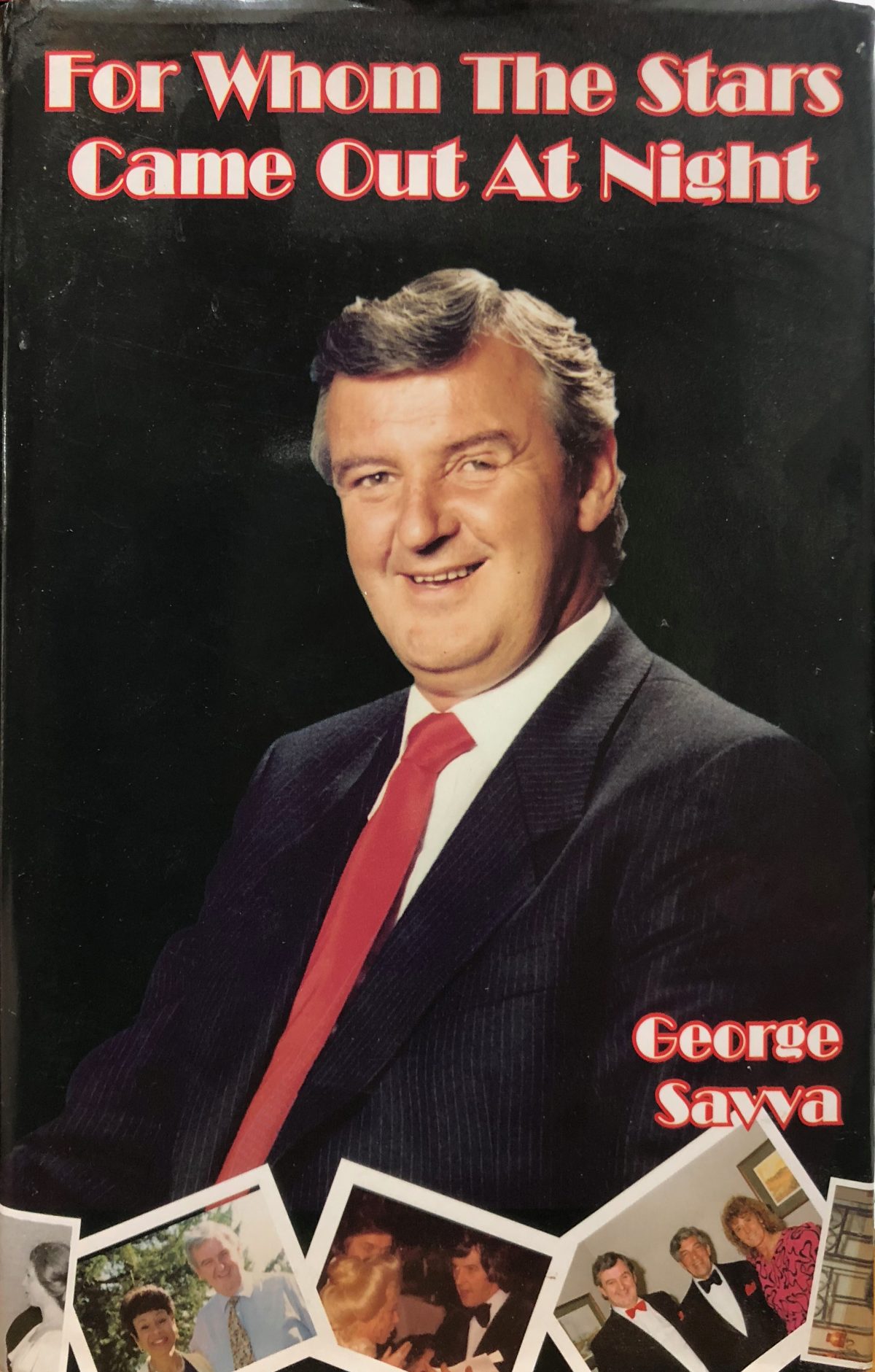

The manager of C’esars, the large Luton club that featured a twenty-lane bowling alley on the first floor, was George Savva, a man who did absolutely nothing to discourage the use of his nickname ‘Mr Show-Business’. In the late 1960s Savva had enough contacts to bring over not only Johnnie Ray but other transatlantic stars such as Jack Jones, Johnny Mathis and Frankie Laine. It was fair to say, however, that some of the big stars found the venue less than glamorous. Tom Jones tells a story of how Shirley Bassey once summoned Savva to her dressing room during a break in rehearsals and said: ‘Are you the manager of this shit-house’? Savva nodded, to which the Welsh singer informed him that she’d refuse to perform unless the dressing room was completely redecorated and a chaise longue found.

It was at about this time when C’esars, which had up to then relied on chicken-in-a-basket and similar meals, started to feature a more sophisticated, upmarket fare. The nightclub/restaurant started serving new dishes, printed in French on a menu that, according to Savva, ‘beckoned the diner seductively’. They included:

Beef Bourgoine (sic), Cock eu Vin (sic), Canard a la Orange (sic), and lastly, and presumably after the useless translator had given up, Venison in Cherry.

Supplied by Alverston Kitchens as frozen bricks, the great advantage of these new-fangled factory foods to large club/restaurants was their almost total elimination of expensive experienced chefs. The meals came in one-portion polythene bags, which were then simply placed in boiling water for about fifteen minutes before they were snipped open, emptied onto a plate and served. Although the frozen boil-in-the-bag meals were far cheaper to produce, Savva later wrote that although he knew it was wrong, ‘my greed got the better of me and I placed a £1 surcharge on the dishes’.

Meanwhile up on stage at C’esars in January 1969, Ray was dressed in a black tuxedo and at about 11.15 p.m. surprised and excited the audience by welcoming Judy Garland up on to the Luton nightclub’s stage. She was wearing a very short white mini-dress with white leather boots, and to the audience looked far more fragile and thin than they remembered. Eighteen years before, in 1951, the newspapers talked of Garland’s weight and the Manchester Guardian, reviewing her successful concerts at the Palladium, described her as ‘a well-built girl in a lot of black chiffon’. The Daily Mail agreed, writing that her dress ‘did little to hide her almost matronly new girth’, while the Sunday Dispatch just simply went with the description, ‘plump and perspiring’. Judy told The Times at the time that it was quite simple: ‘Fat I’m happy, and thin, I’m miserable.’

An ‘overweight’ Judy Garland on stage at The Empire Theatre in Glasgow 1951

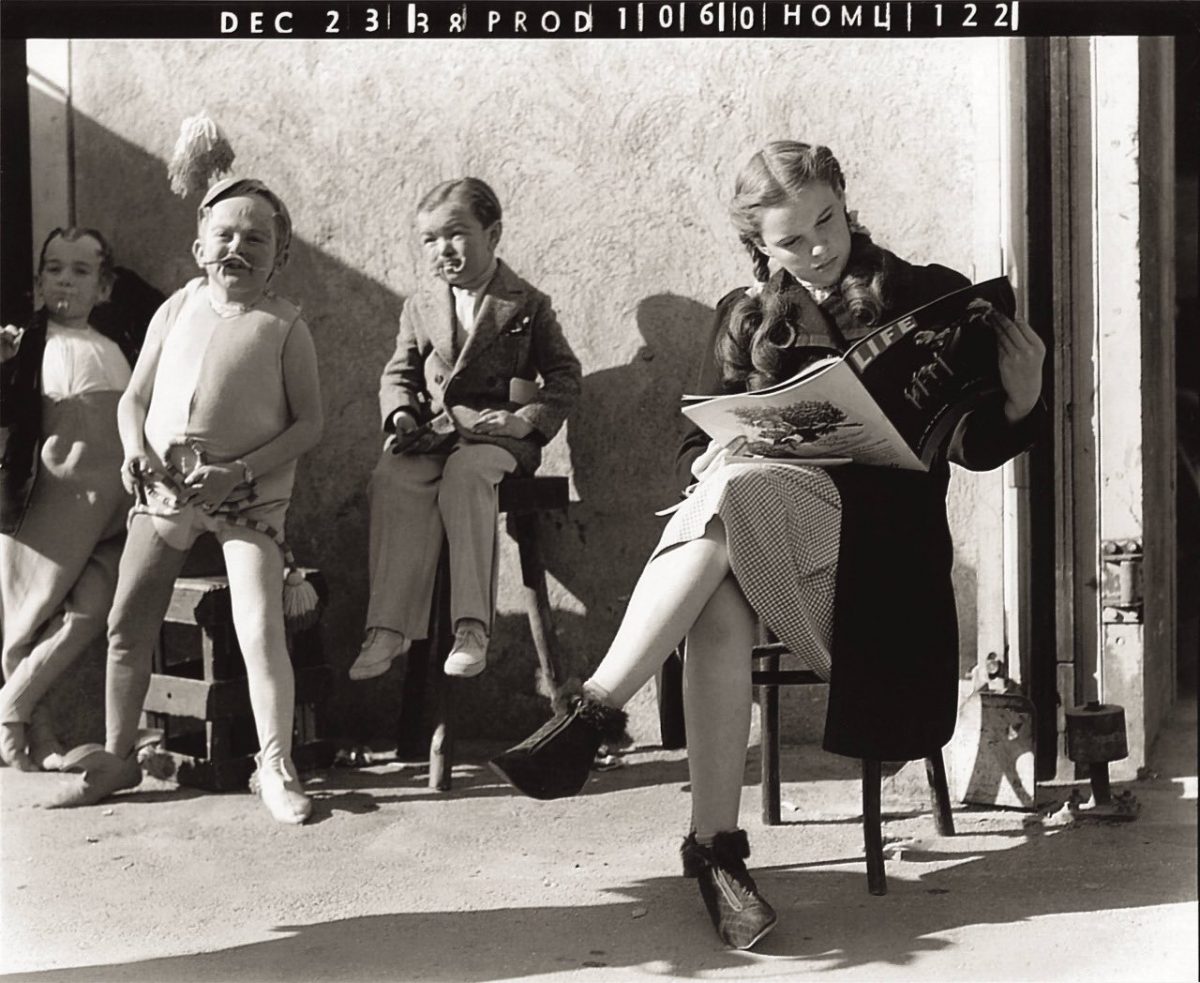

Garland had been taking drugs since she was in her early teens, essentially to keep her weight down – Louis B. Mayer, the owner of MGM, called her ‘that fat kid’ (not to mention ‘my little hunchback’ – you can understand why she had trouble with self-esteem all her life) and was constantly troubled by what he saw as her weight problem. Studio doctors prescribed the new wonder drug Benzedrine, and subsequently the more sophisticated offshoots Dexedrine and Dexamyl. Back then drugs like these seemed like miracles of science and were almost as common as aspirin.

Despite the comments about her weight, the first night at the Palladium in 1951 was an absolute triumph. Even after she tripped and landed on her backside after the fourth song (the audience howled with laughter at her unfortunate mishap) the appreciation at the end of the show was extraordinary. Before she had even finished singing ‘Somewhere over the Rainbow’, her last song, the audience was so loud and effusive that Val Parnell, the managing director of the Palladium, and someone who had seen a few, described it as the biggest ovation he had ever seen or heard.

Eighteen years later at C’esars the American stars sang the song ‘Am I Blue’ as a duet, at the end of which the crowd leapt to their feet and gave the two stars a five-minute standing ovation. George Savva, however, described it as the most awful performance of the song he had ever heard and said that the ageing superstars sang not only out of tune but out of sync. Something must have worked because he added, ‘It was also one of the most moving nights of my life!’

Not long after finishing the duet, Judy Garland was back in her black limo which, via the ten-year-old M1 motorway, drove her to her nightly show at the Talk of the Town at the Hippodrome on Charing Cross Road. She had been booked for five weeks from the very end of 1968 and her first show, on 30 December, with Zsa Zsa Gabor, Ginger Rogers, David Frost and Danny La Rue13 in attendance, was a huge success. With echoes of her Palladium triumph, Bernard Delfont described the audience roaring their approval like ‘a football crowd at a cup-final’.

For that first night Garland wore a bronze sequinned trouser suit, originally designed for the movie Valley of the Dolls and first worn in 1967. In Jacqueline Susann’s original book the character Neely O’Hara, whose talent was blunted by self-destructive alcoholism and a dependency on prescription drugs, was purportedly based on Garland. The American singer had been utterly addicted to Seconal (the drug that would eventually kill her) off and on since the 1950s. Seconal, a barbiturate derivative medicine, became widely misused in the sixties and had nicknames such as ‘reds’, ‘red-devils’ or ‘seccies’. Another common name for the pills, especially in California, was ‘dolls’ and thus responsible for the punning title of Jacqueline Susann’s novel – ‘Valley of the Dolls’. Judy was actually cast in the film, not as O’Hara but to play the character Helen Lawson. Not long into the filming Garland, not helped by the drug

Johnnie Ray, a gay or bisexual man who was never in a position to acknowledge, publicly, his sexuality, suffered from alcoholism throughout his life. After he was hospitalised with tuberculosis in 1960 he stopped drinking and for a few years was in a long-term relationship with his manager Bill Franklin, a man thirteen years his junior. In 1969, not long after his friend Judy had died, an American doctor told Ray he was now well enough to enjoy the odd glass of wine. It was bad advice; the heavy drinking resumed and he never really recovered. Ray died of liver failure in 1990 and is buried in Hopewell, Oregon.

Five years after Garland’s death, Johnnie Ray was still performing ‘Am I Blue’, the song he sang with Garland on stage at C’esars in Luton, as a sort of ‘duet’. Barry Coleman of the Guardian reviewed a 1974 Johnnie Ray concert in Chorley: ‘The spotlight on the absent, not to say dead, Judy’s stool seemed a bit much. But that, as sure as hell, is showbiz.’

“Cry” was written by Churchill Kohlman, a black man working as a night watchman at a Pittsburgh dry cleaning factory.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.