“I, the miserable and the abandoned, am an abortion to be spurned at, and kicked, and trampled on.”

– Frankenstein’s lament, Mary Shelley

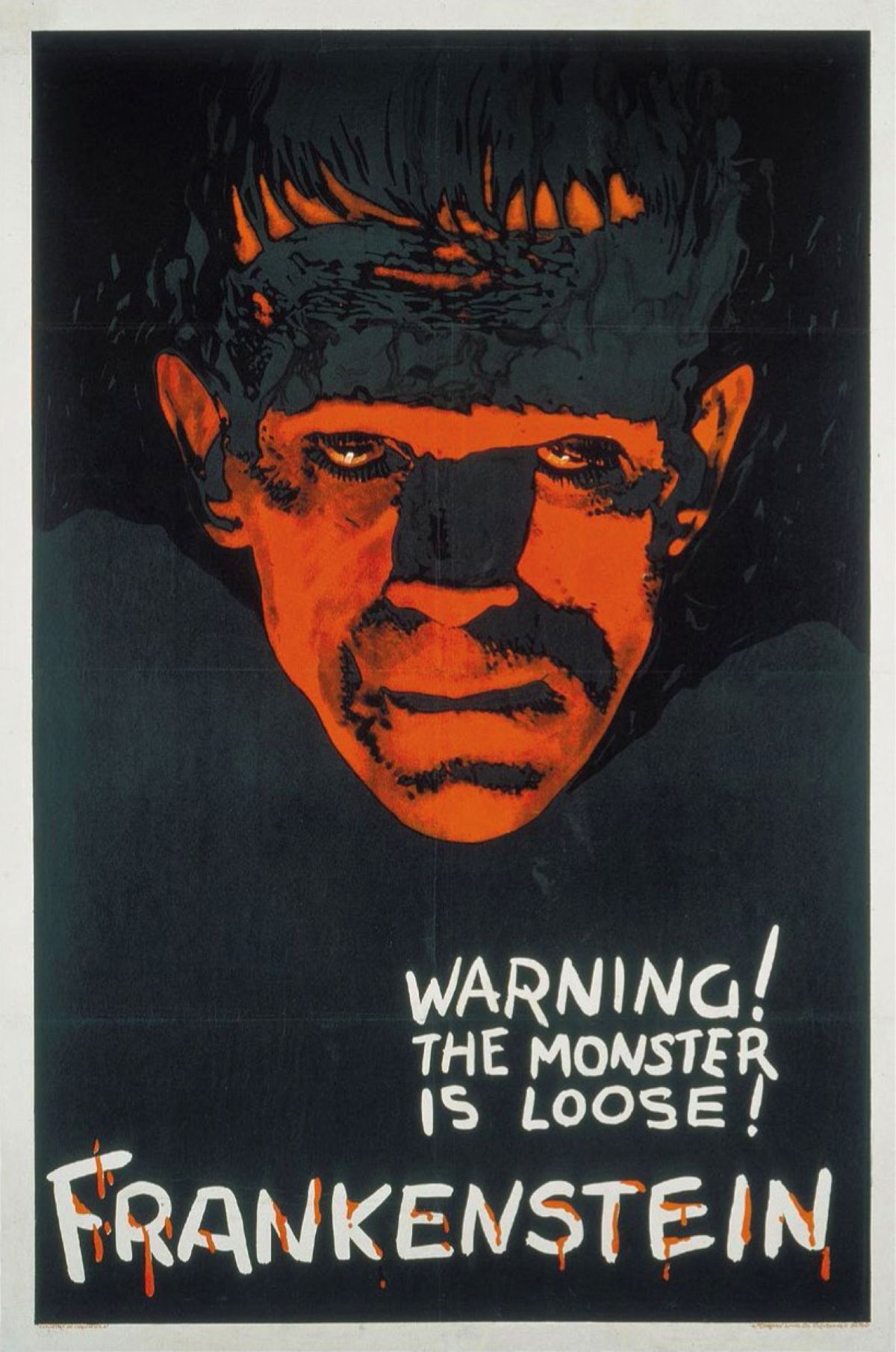

‘Frankenstein‘ 1931.

In 1816, 18-year-old Mary Shelley (nee Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin; 30 August 1797 – 1 February 1851), Percy Bysshe Shelley (4 August 1792 – 8 July 1822) and their months-old son, William, were taking the air near Switzerland’s Lake Geneva. As the rain fell on a dark and stormy night (natch.), their host, Lord Byron, invited them and the rest of the party – the Shelleys, Mary’s step-sister Claire Clairmont, Lord Byron and his physician John Polidori – to see if they could write a scary story.

Soon after, Mary experienced hallucinations. Then a dream:

When I placed my head on my pillow, I did not sleep, nor could I be said to think. My imagination, unbidden, possessed and guided me, gifting the successive images that arose in my mind with a vividness far beyond the usual bounds of reverie. I saw — with shut eyes, but acute mental vision, — I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion.

Many of us keep pencil and paper by our beds for just such moments, to jot down the lyric that made us hum, the joke that made us wake up laughing. We wake to read something intelligible, smudged and drab. Mary woke and set about writing the story Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. The story, with a run of 500 copies, was published as a three-volume novel in London on 1 January 1818.

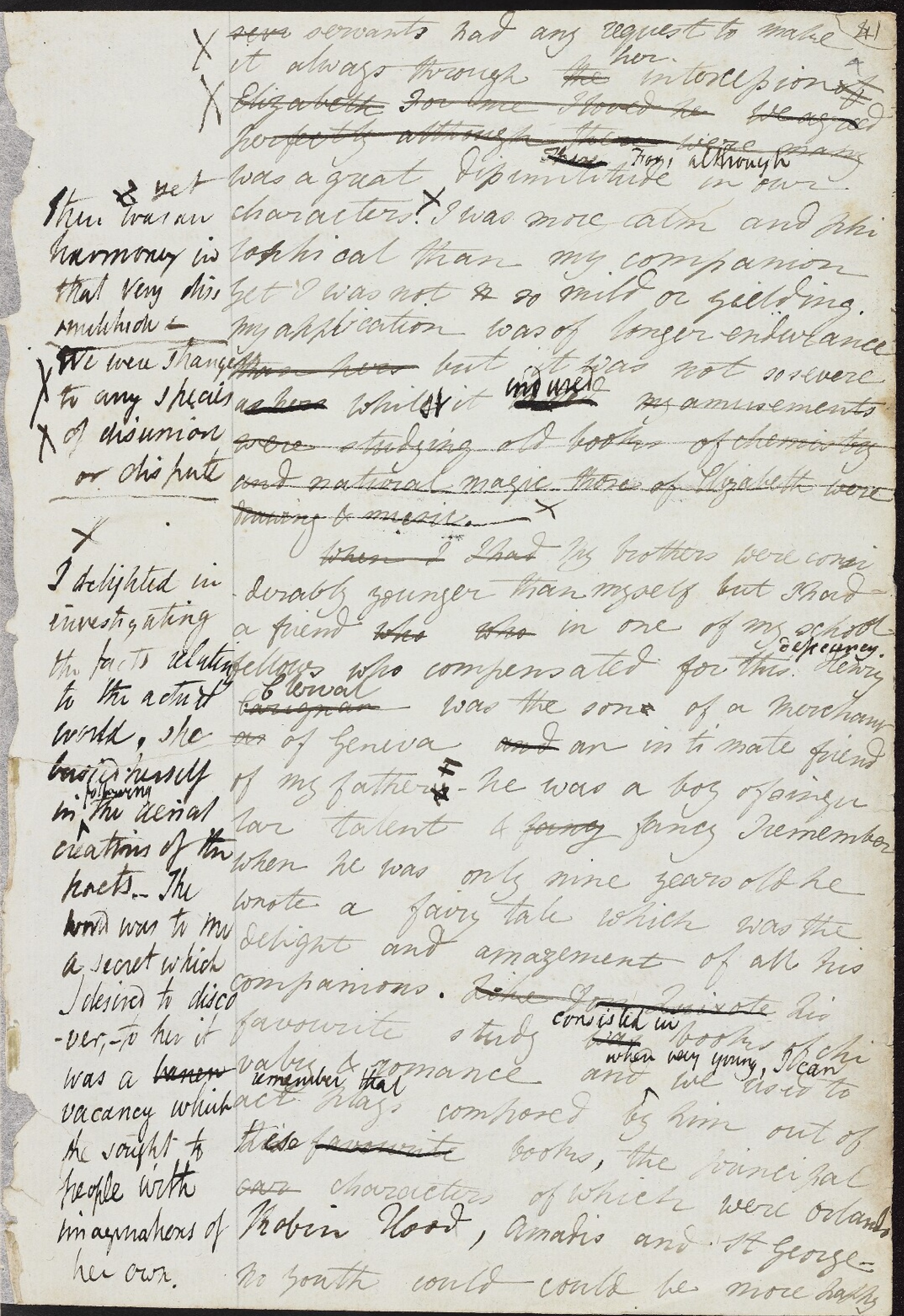

Unlike most midnight scribbles that ended up in the bin, Shelley’s series of notebooks “can now be viewed in high quality, resizable page images” at the Shelley Godwin Archive.

Richard Rothwell’s portrait of Mary Shelley in later life was shown at the Royal Academy in 1840

In the introduction to the book’s 1931 edition, Mary paraphrased a question she was often asked: “How [did] I, then a young girl, [come] to think of, and to dilate upon, so very hideous an idea?” The question is laughable. This is the Mary Shelley, who aged sixteen and pregnant had eloped to Europe with married Percy Shelley, whose wife Harriet Shelley was pregnant. Mary’s child, Clara, died at 10-days old. As Mary wrote in a journal: “find my baby dead. A miserable day.” A few months later, Harriet drowned, pregnant by another man.

On March 19, 1815 Mary recorded the following dream in her journal:

“Dreamt that my little baby came to life again; that it had only been cold, and that we rubbed it before the fire, and it lived. Awake and find no baby. I think about the little thing all day. Not in good spirits.”

Her son William died in June 1819. He was named after her father, who’d disowned her on account of her love for Shelly. A second child named Clara died on a trip to Rome, a few months before Percy died (drowned) in the same city. Her mother, the pioneering feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, died of complications from childbirth exactly a month after bringing Mary into the world. Why did she write a story that reaches to the heart of life through creator and creation, feelings and science?

What could a young girl know of life?

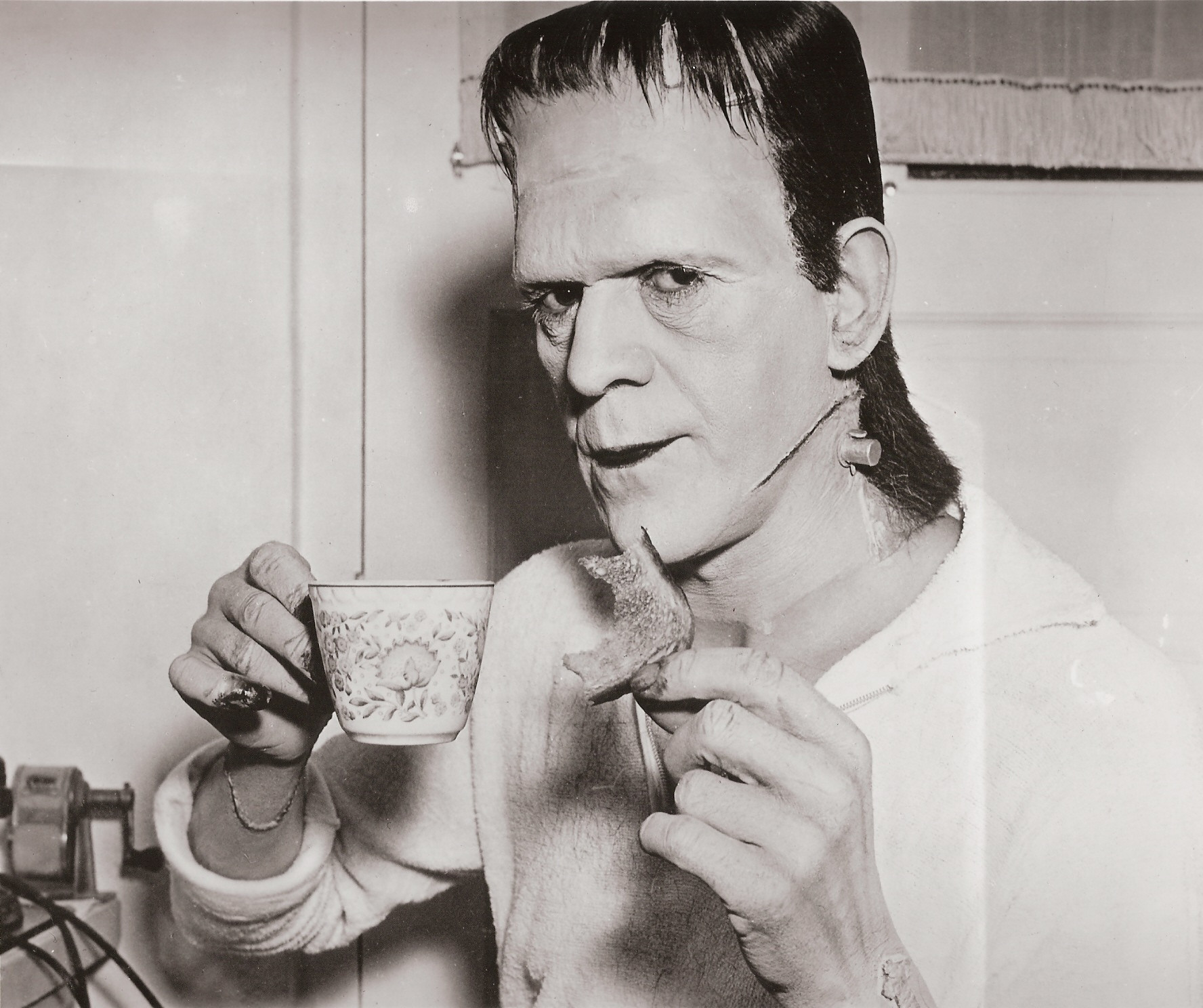

Boris Karloff having a nice cup of tea and a piece of toast between shots of Frankenstein, released in 1931.

And now a little interjection, if you don’t mind. Weird science was in the air.

In 1817, the German scientist Karl August Weinhold removed the brain from a live kitten and replaced it with an amalgam of silver and zinc. According to Weinhold, the cat “opened its eyes, looked straight ahead with a glazed expression… hobbled about, and then fell down exhausted”.

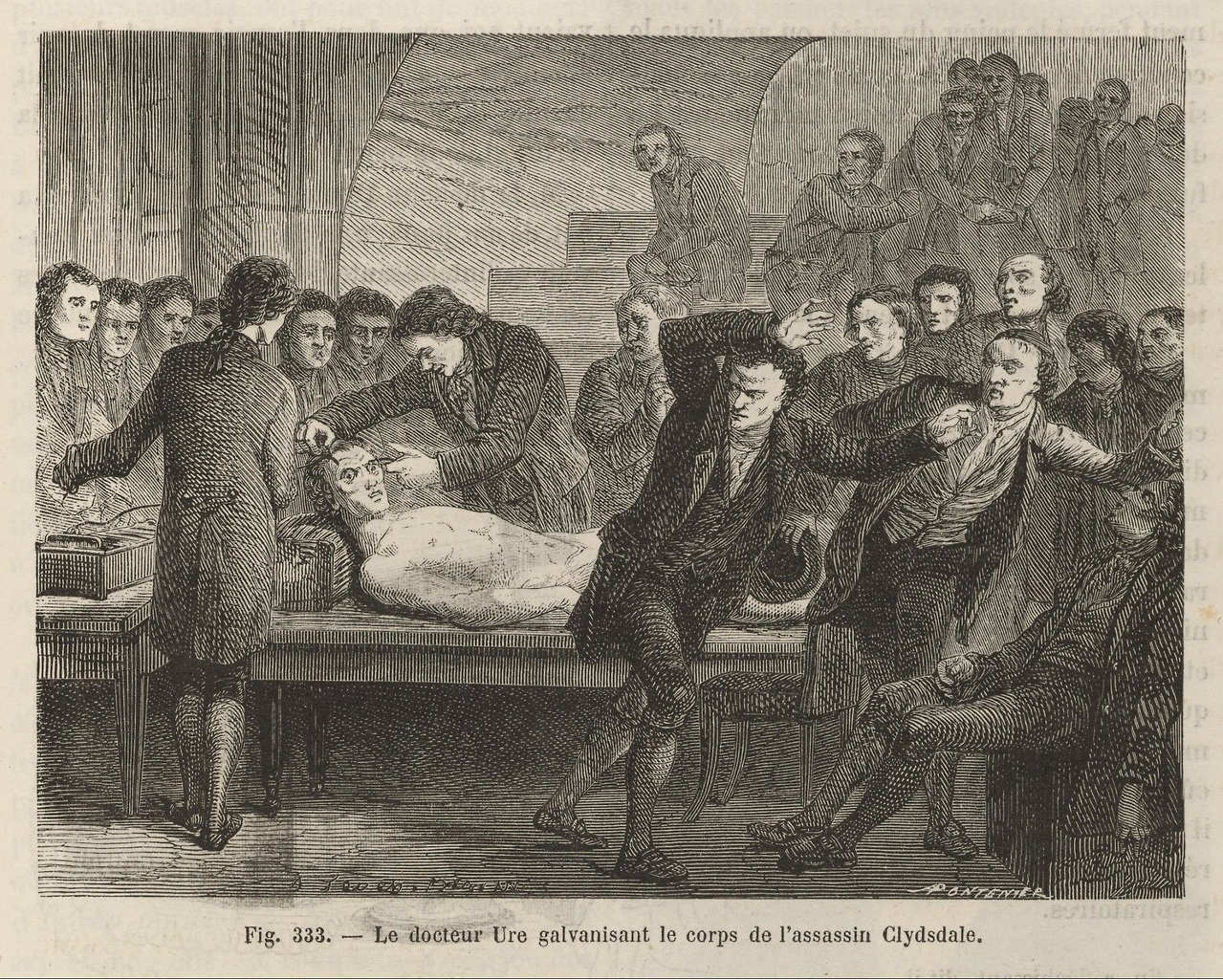

1867 engraving of Ure’s galvanic experiments on a murderer named Matthew Clydesdale

Giovanni Aldini used electricity to stimulate expressions in the heads of executed criminals. In 1818, Scottish chemist Andrew Ure adapted Aldini’s methods to induce “life” in a criminal’s corpse. He claimed that, by stimulating the phrenic nerve, life could be restored in cases of suffocation, drowning or hanging.

Every muscle of the body was immediately agitated with convulsive movements resembling a violent shuddering from cold… On moving the second rod from hip to heel, the knee being previously bent, the leg was thrown out with such violence as nearly to overturn one of the assistants, who in vain tried to prevent its extension. The body was also made to perform the movements of breathing by stimulating the phrenic nerve and the diaphragm. When the supraorbital nerve was excited ‘every muscle in his countenance was simultaneously thrown into fearful action; rage, horror, despair, anguish, and ghastly smiles, united their hideous expressions in the murderer’s face, surpassing far the wildest representations of Fuseli or a Kean. At this period several of the spectators were forced to leave the apartment from terror or sickness, and one gentleman fainted.”

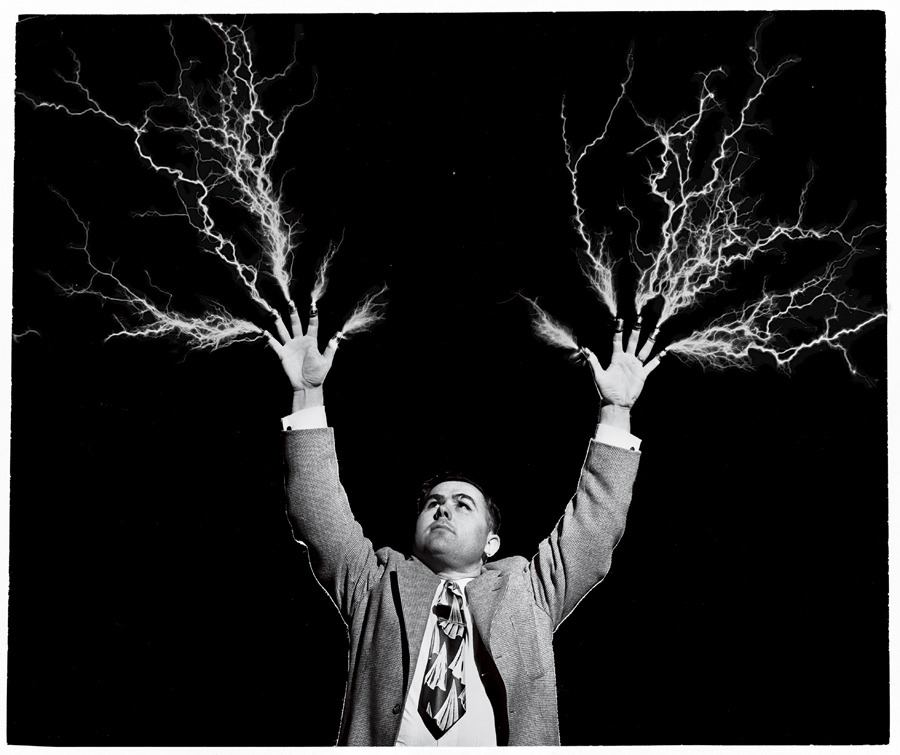

Something electric was in the air back then.

Electricity flashes from the thimble-topped fingers of a “preacher-scientist,” August 1955. Photograph by the Moody Bible Institute (via Stephen Ellcock)

“I had worked so hard for nearly two years for the sole purpose of infusing life into an inanimate body. For this I had deprived myself of rest and health. I had desired it with an ardor that exceeded moderation; but now that I had finished, the beauty of the dream vanished, and breathless horror and disgust filled my heart.”

– Mary Shelley

Mary Shelley’s writing and notes – Page 1

Funded by The National Endowment for the Humanities and The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation, the archive was assembled by the University of Maryland’s Institute for Technology in the Humanities, The New York Public Library, the Bodleian Library, The Huntington and the Harvard University Library.

Via: Open Culture, Charles E. Robinson’s The Frankenstein Notebooks, Parts One and Two.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.