“We had the launch party at the Roundhouse in Camden. It had been used for storing gin, and had been abandoned for seventeen years. It was just a big space with a balcony that was apparently unsafe. But it was ideal for IT. Soft Machine and The Pink Floyd played. I remember paying them – Pink Floyd got £15 because they had a light show, and Soft Machine got £12. Although they had a motorcycle on stage, so maybe that was a bit unfair.”

– Barry Miles

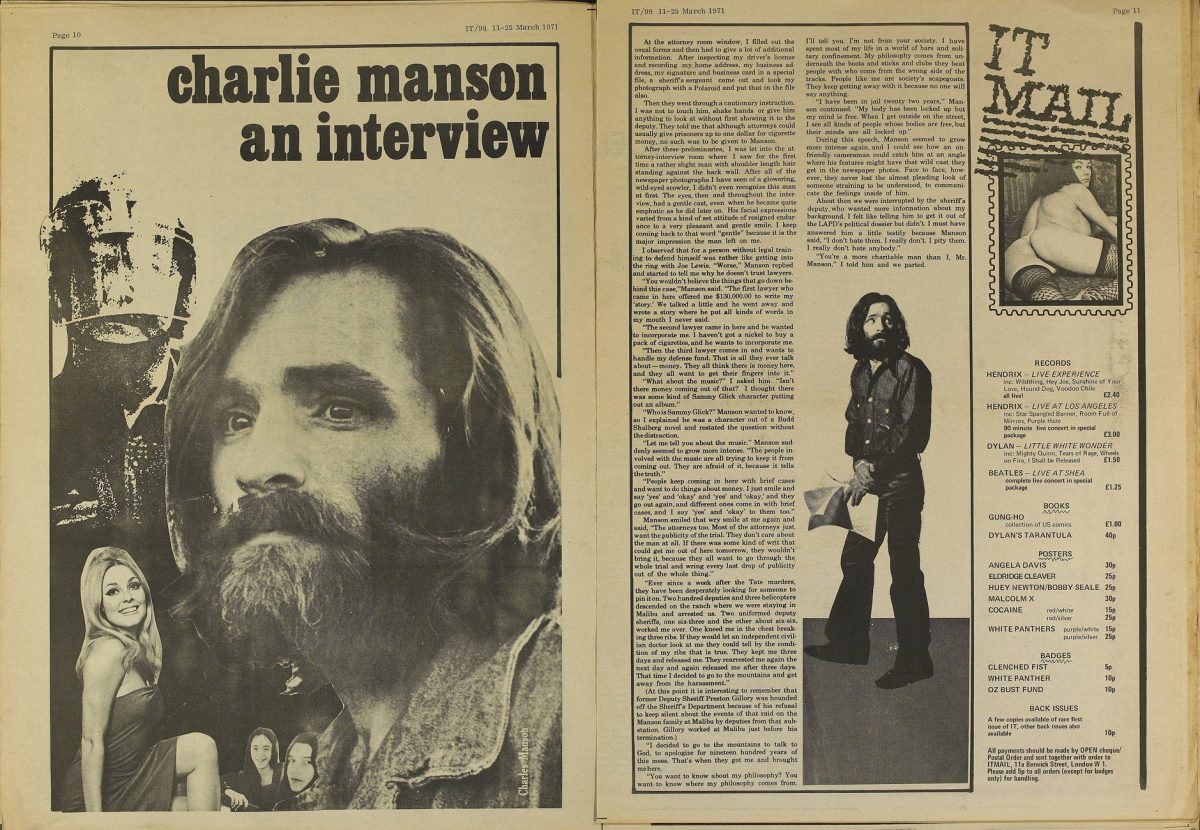

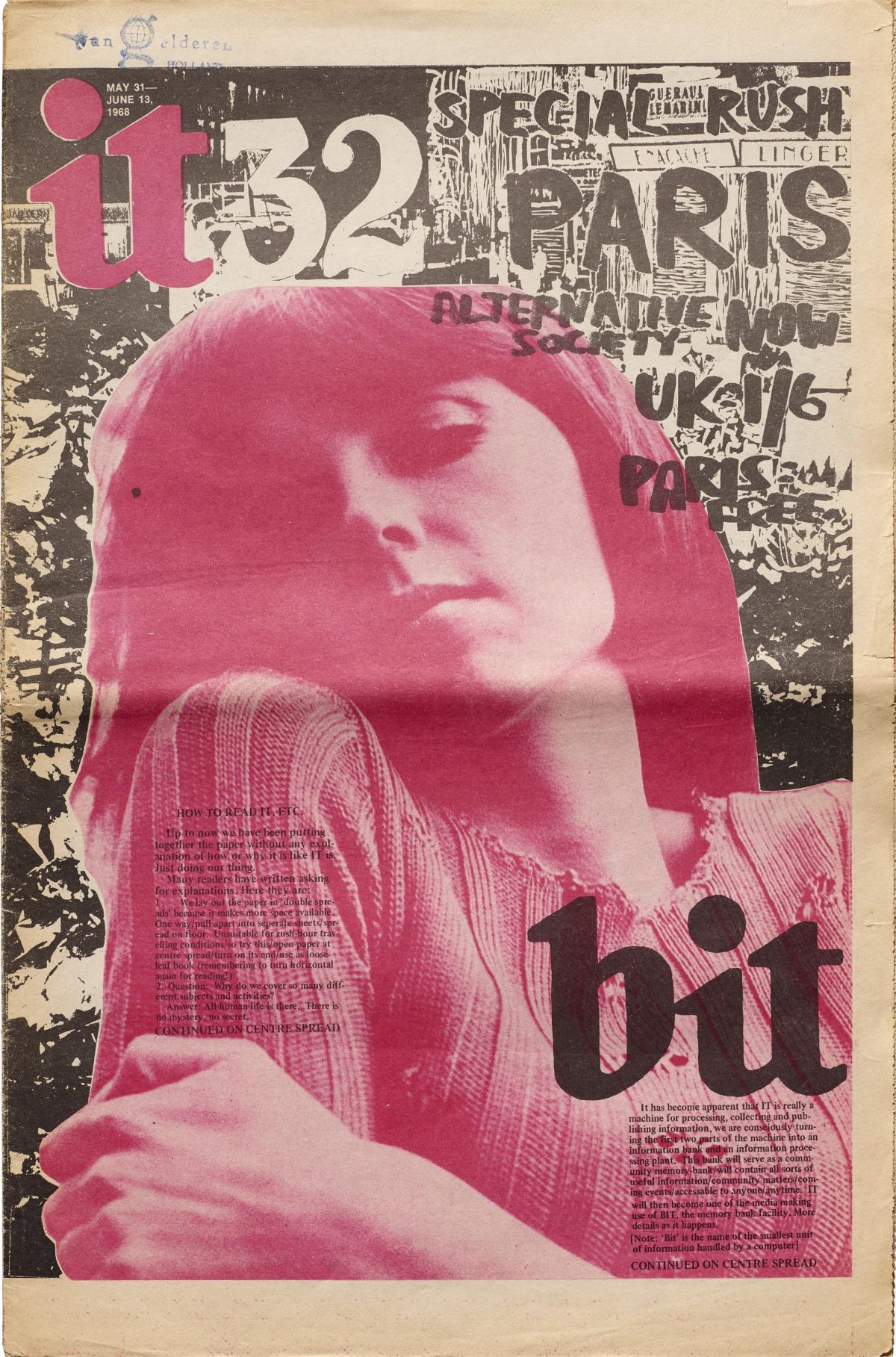

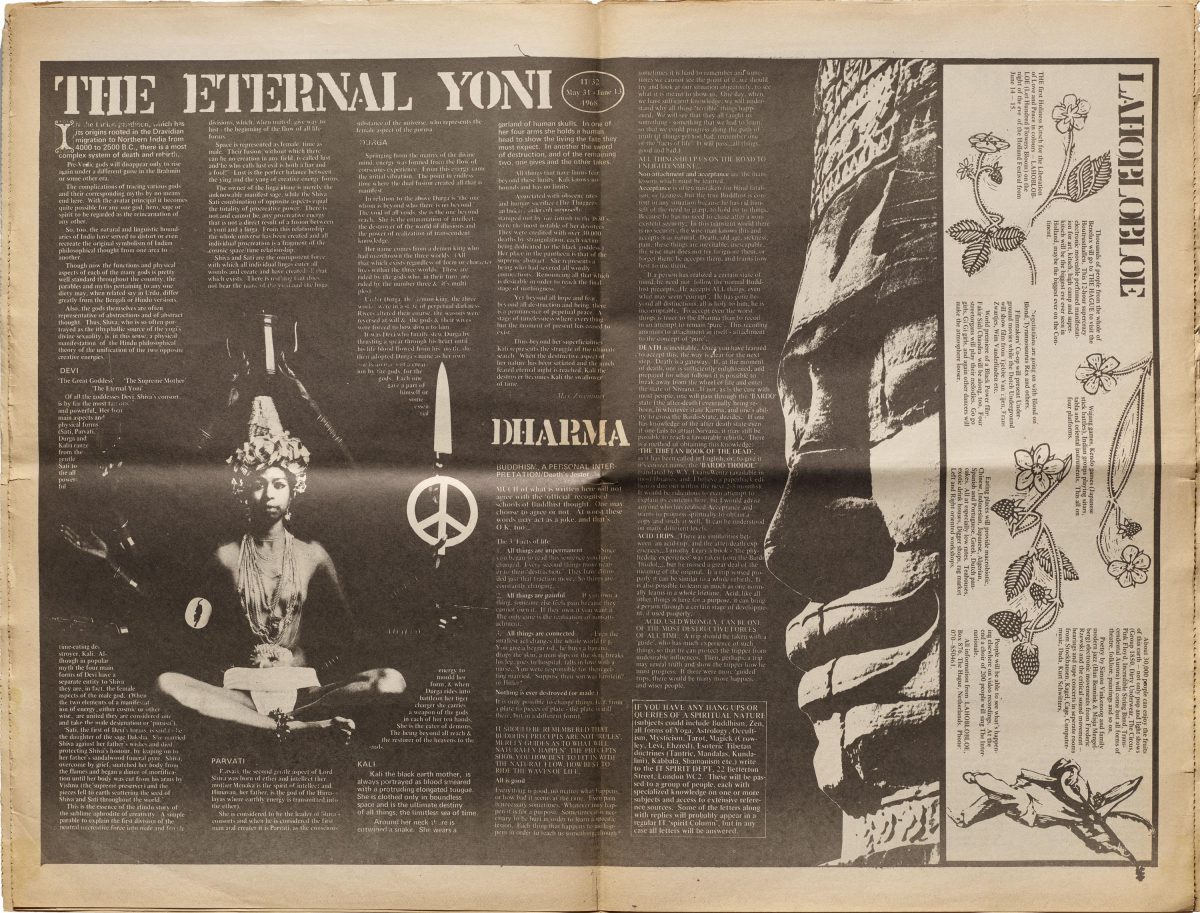

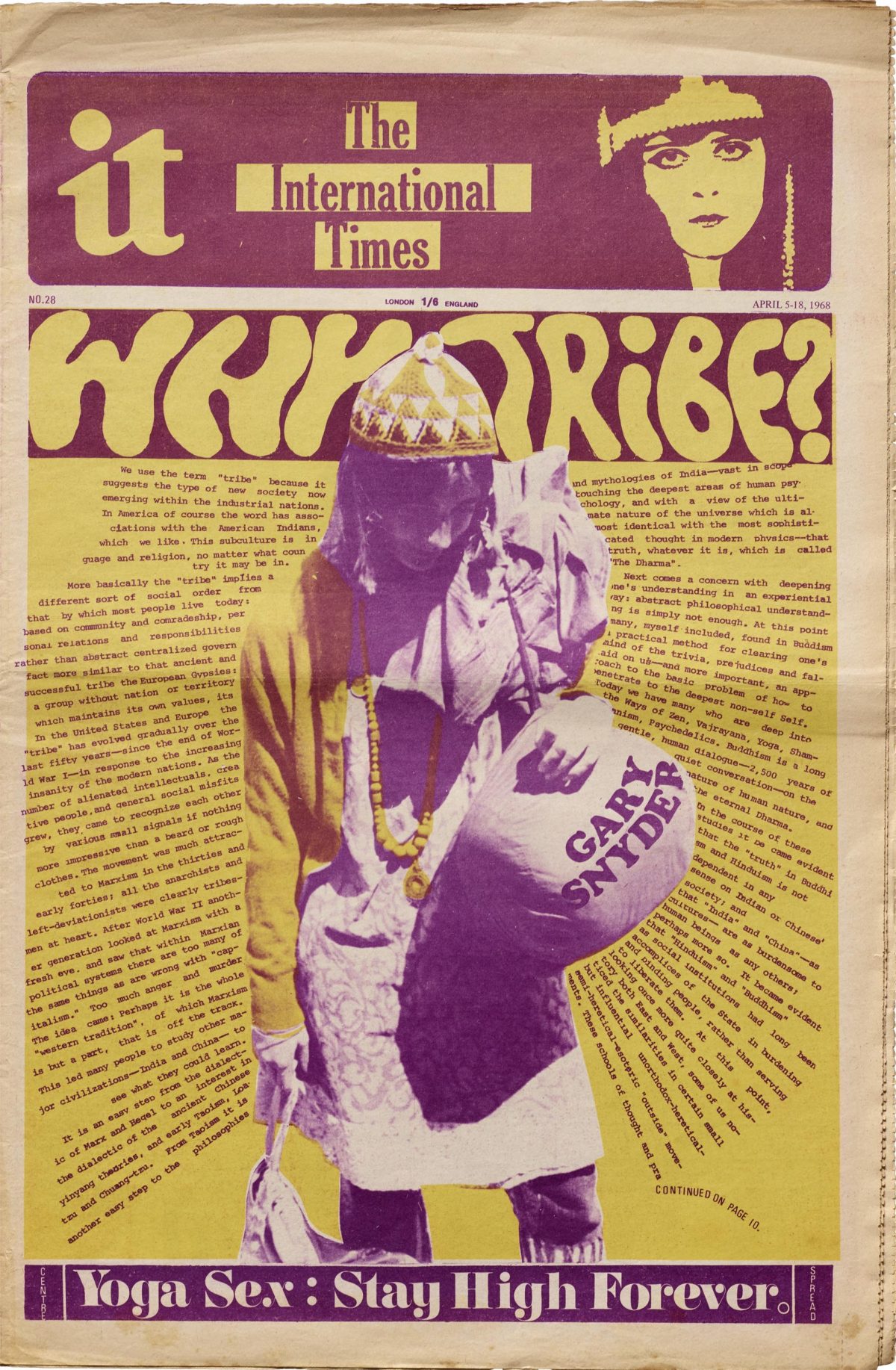

“Holy cow! It’s another dirty commie smut rag!” exclaims Captain America from the cover of a March 1971 issue of International Times. Unlike many of its later imitators, the now-infamous International Times of London, or IT (as it was compelled to call itself after a lawsuit by the Times), wielded its irreverent, satirical, often juvenile sense of humor as a weapon against real censorship and state repression. Five years after its 1966 founding, the pioneering underground paper had weathered more than its share of police raids and lawsuits. It had also published what must be the most sympathetic interview with Charles Manson ever recorded, ending with the send-off, “You’re a more charitable man than I, Mr. Manson.”

In 1973, the first, radically original iteration of IT was forced to shut down after a conviction for running ads for gay men to contact each other. It reappeared later at various times under various other publishers over the next several decades and briefly tried to compete with glossier magazines. But never again after the early seventies did the underground “dirty commie rag” so scandalize conservative British society while also publishing some of the most prominent voices of the counterculture and launching a sustained critique against the monarchy and the staid literary establishment ( in particular, the poetry world).

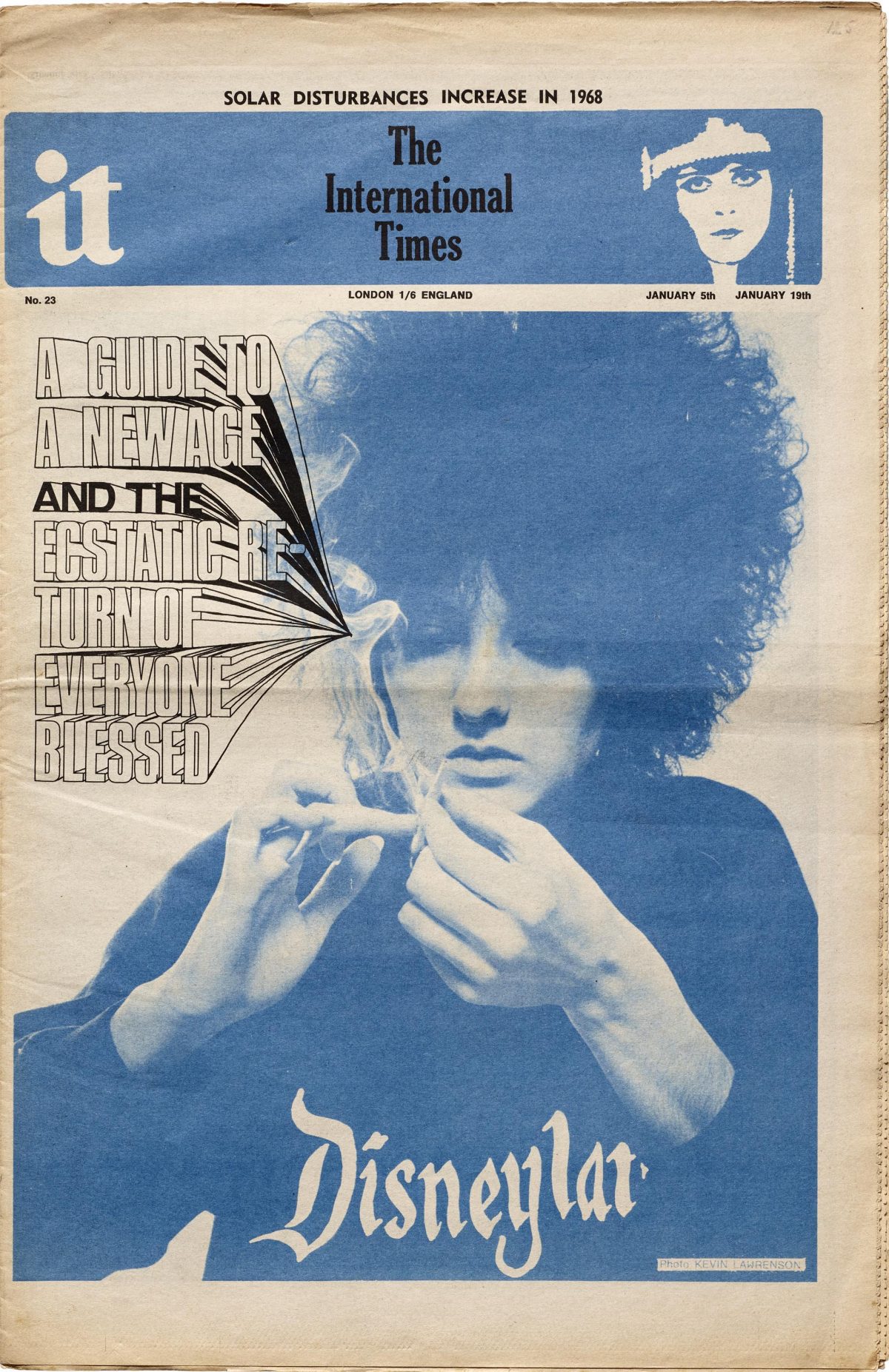

As co-founding editor Barry Miles tells it, according to journalist Alex Watson, “It’s very, very difficult now to imagine how straight England was, even in the mid 60s. It was a very black and white world then… The idea of anyone from our community writing for the Guardian or the Times was inconceivable. None of the papers had any popular music coverage in those days. Our group of people needed somewhere to express themselves, so in early 1966, Hoppy (John Hopkins) and I started to put it together.”

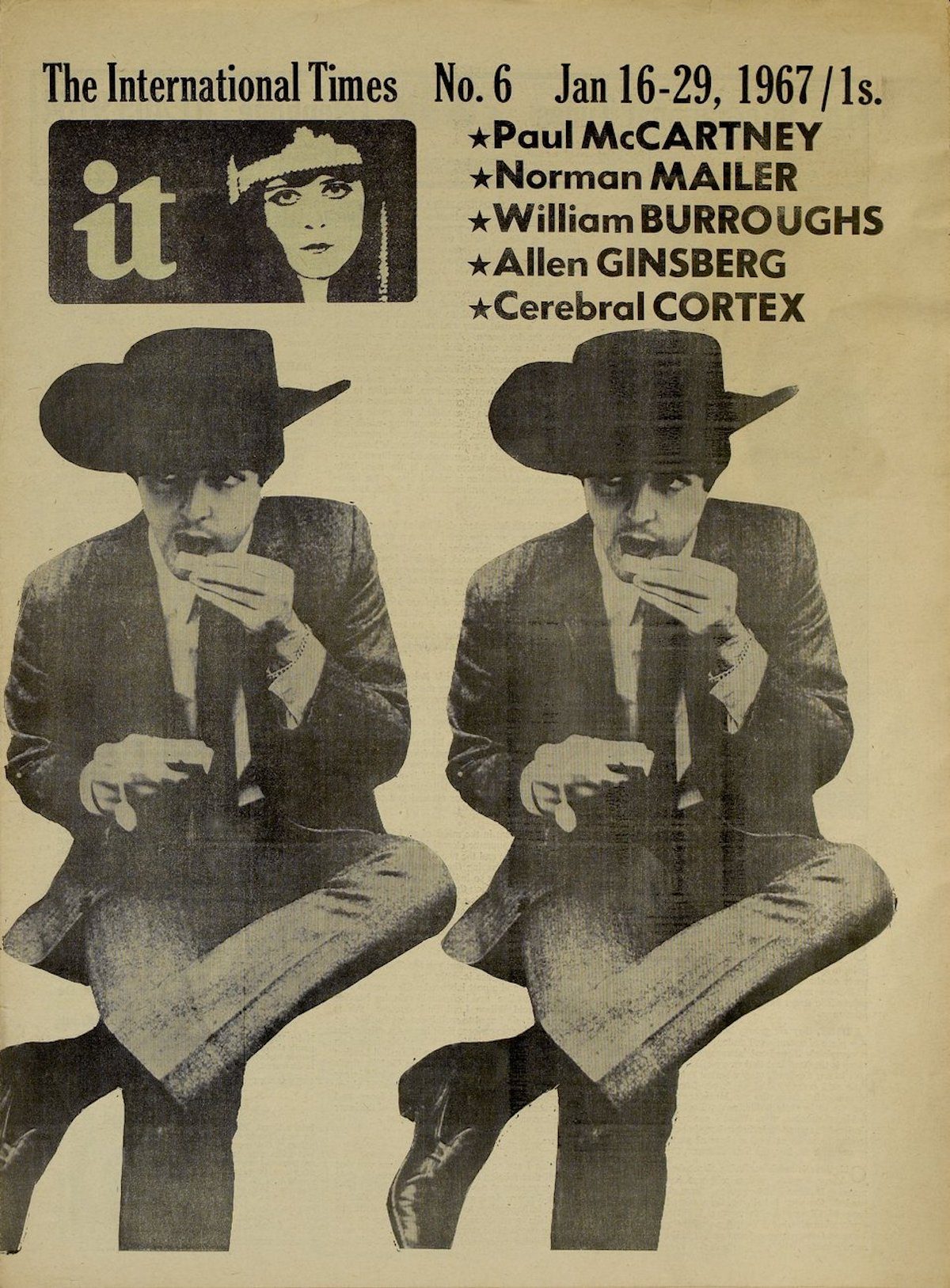

They did so with backing from Miles’ friend Paul McCartney, whom Miles had first introduced to hash brownies with a recipe from The Alice P. Toklas Cookbook. The paper was launched in 1966 with a benefit promoted as an “All Night Rave” and featuring Soft Machine and Pink Floyd. Another 1967 benefit at London’s Alexandra Palace featured Pink Floyd, Yoko Ono, The Crazy World of Arthur Brown, and more. The “straight” world fought back, as Dugald Baird writes at The Guardian:

Like fellow underground title Oz, whose editors (including Richard Neville, Jim Anderson and future magazine mogul Felix Dennis) faced notorious obscenity trials, IT experienced continual harassment from the authorities. The paper’s offices were raided for the first time in March 1967, when 8,000 copies were seized on grounds of obscenity. The charges were later dropped. In 1970 it charged with conspiracy to corrupt public morals by printing gay contact ads in its back pages. It was convicted in 1972 and temporarily closed down.

Although multiple police raids failed to put IT out of business for years, it continued to need funds. The paper’s many “heavyweight supporters” helped keep it afloat, says Miles:

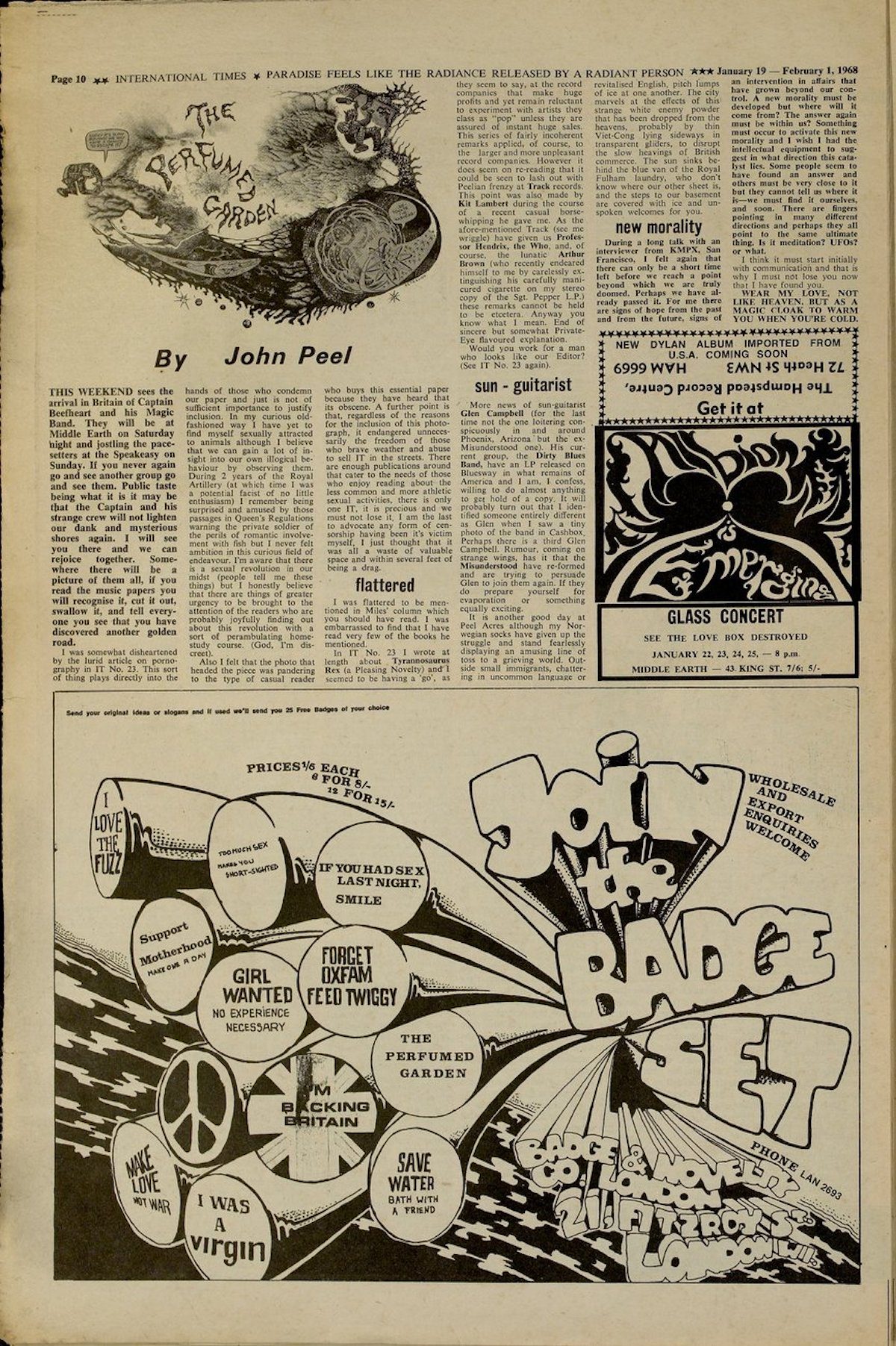

The first few issues had a lot of serious articles by William Burroughs about the overthrow of the state. He used it as his platform to work out his ideas. And there was Ginsberg too. All the usual suspects. When we were running out of money, I was talking to Paul McCartney about it, and he said, ‘Well, you should interview me, then you’ll get ads from the record companies.’ And I thought, ‘hey, he might be on to something.’ So I interviewed him, and then George Harrison, and then the next week Mick Jagger called up, demanding to be interviewed too. And Paul was right, we got ads from the record companies.

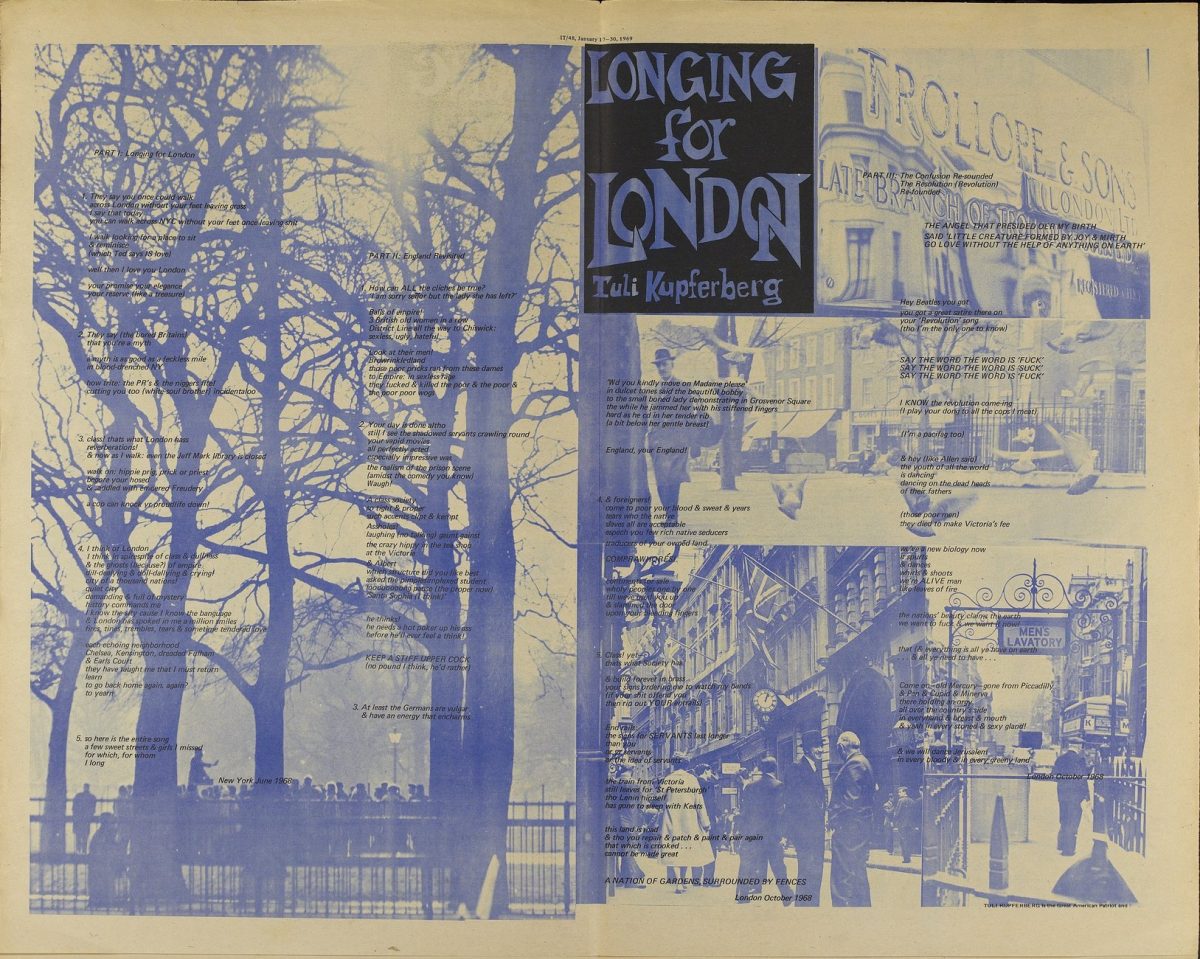

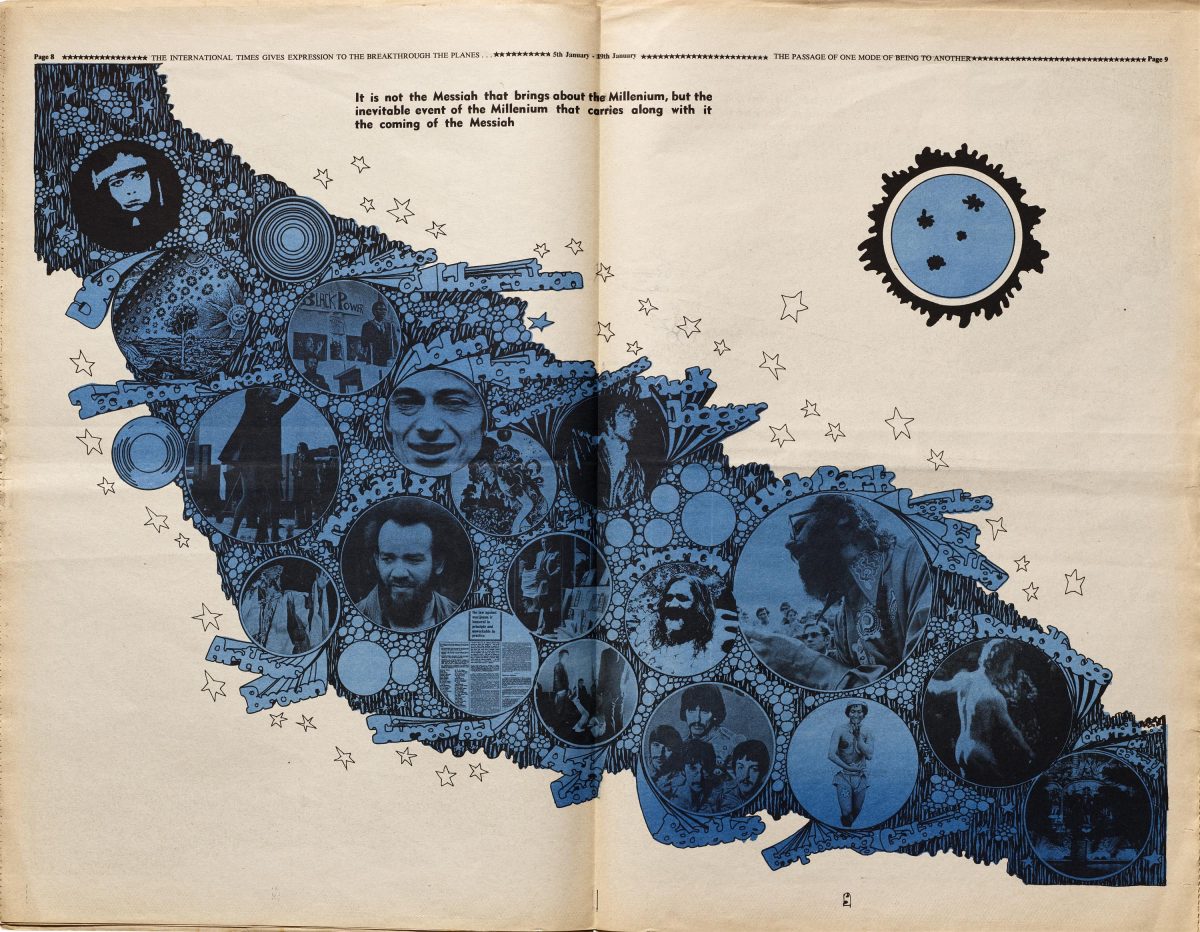

While McCartney participated in supporting the magazine (and Miles later worked for Apple records, producing LPs of poetry by Richard Brautigan and Allen Ginsberg), the paper retained an aggressively egalitarian, contrarian editorial independence bordering on the anarchic. “IT wasn’t properly edited,” says Miles. “It depended a lot on people bringing stuff in.”

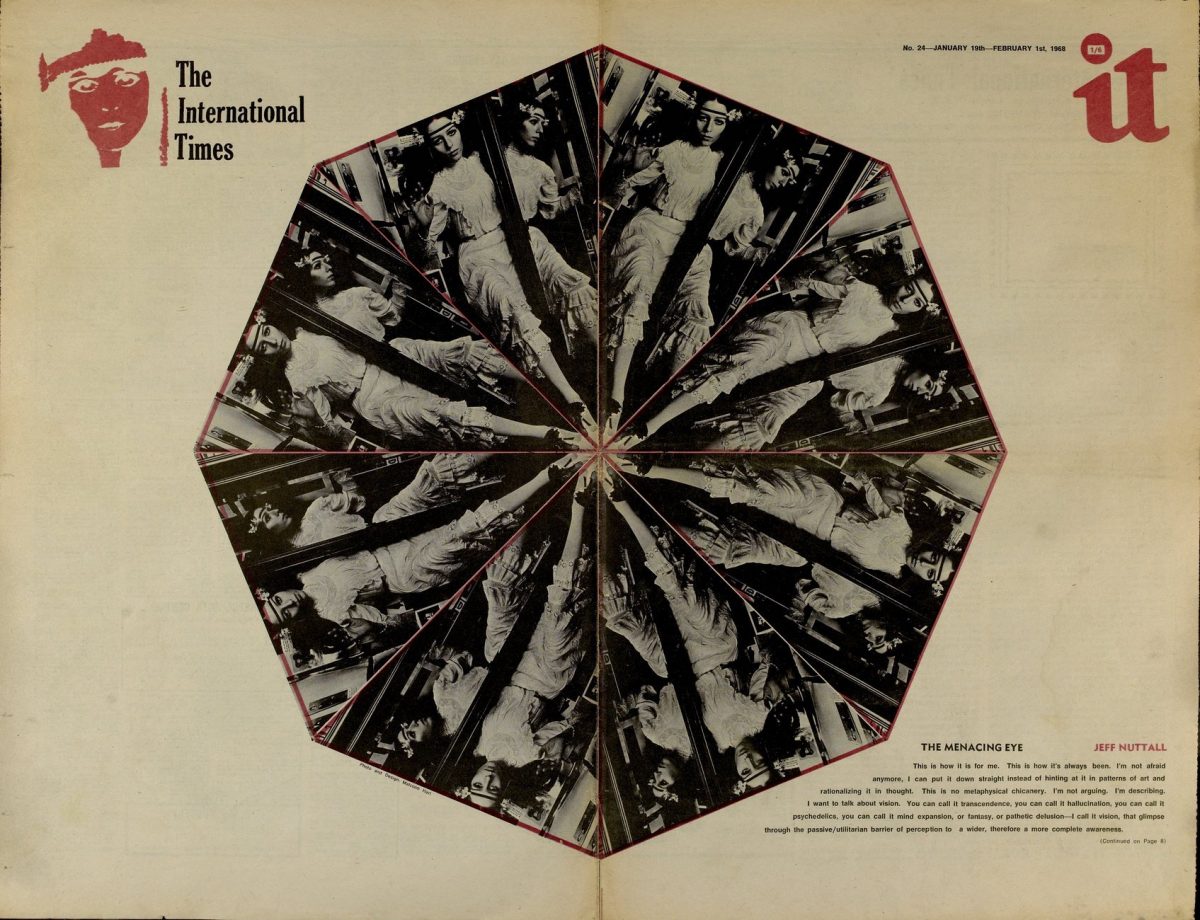

In a February 1968 issue, Allen Ginsberg wrote a critical review of the Maharishi’s appearance at the Plaza hotel the previous month. Despite his special status for countercultural celebrities like the Beatles, Ginsberg found him none too impressive and didn’t decline to say so — both to the assembled devotees at the time and later in print. He described many of the guru’s statements as “inexperienced or ignorant and unfamiliarly authoritarian,” as well as “dim-witted.” Nothing was sacred to the many editors of the International Times during its first, seven-year run, but its thoroughgoing irreverence was as much a deliberate offense against what its publishers saw as the phony decorum of Fleet Street as it was a natural byproduct of the contributors’ heterodox attitudes.

While the underground paper’s format influenced the genesis and growth of periodicals like Time Out, the oppositional attitudes and underground knowledge contained within the pages of IT may have existed in few other places in print outside the U.S. and France at the time. All of that is on display in an online archive of all the original issues. “It seems fitting,” writes Baird, “given the ethos of the paper, that it lives on as an internet resource; in a sense, the ‘community’ that it once served has now moved online.” In a sense, so has everything else, including the latest version of IT, “the magazine of resistance.” Several of the magazine’s former writers — such as Germaine Greer and John Peel — have shown up often over the past several years in mainstream publications like The Guardian. But they first appeared in the page of IT.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.