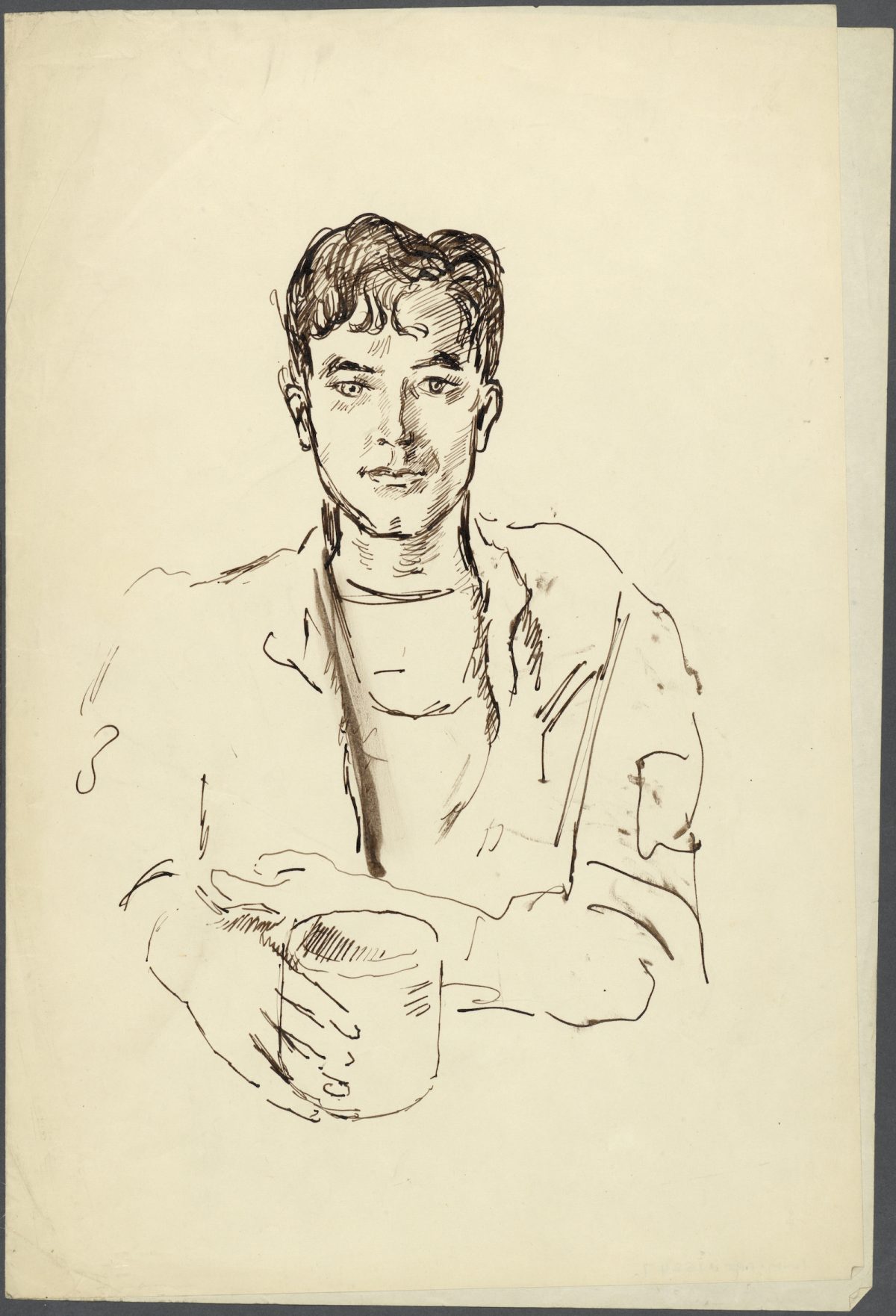

Untitled Portrait.

Cecil Beaton had been a bad boy. In 1938 he was sacked from his job as artist and photographer for Vogue after inserting the word “kike” and other anti-semitic phrases into illustrations for an article on New York society.

Beaton returned shame-faced to England allegedly “appalled” by his “moment of madness.” Though probably more aghast at the damage to his reputation and the loss of his career in America.

His problems were small fry compared to horrific events occurring on mainland Europe which were about to change Beaton’s fortunes. The Second World War proved to be the making of Cecil Beaton and re-established him as a gifted photographer and artist, despite his anti-semitic outburst.

It was the Queen who recommended Beaton to the Ministry of Information, where he was employed as a War Photographer. It was a great relief to Beaton who felt:

…frustrated and ashamed. This war, as far as I can see, is something specifically designed to show up my inadequacy in every possible capacity. I am too incompetent to enlist as a private in the army. It’s doubtful if I’d be much good at camouflage — in any case my repeated requests to join have been met with, ‘You’ll be called if you’re wanted.’ What else can I do?

The Ministry of Information were equally “baffled”. As Beaton was a “special case” it was debated whether he should wear a uniform or not? And whether he would be a private or a non-commissioned officer? It was decided to give Beaton a uniform in case he was captured and shot as a spy.

His British Forces Identity Card was #55561. Beaton photographed London during the Blitz. He travelled all across England and then far and wide across Europe, Africa and Japan sending back despatches. He “was one of Britain’s hardest working war photographers during the Second World War.”

As an official photographer for the British Ministry of Information, Beaton travelled far and wide to document the impact of war on people and places in his own unique style. In later life, Beaton came to regard his war photographs as his single most important body of photographic work. He took some 7,000 photographs for the Ministry of Information covering all aspects of the Second World War.

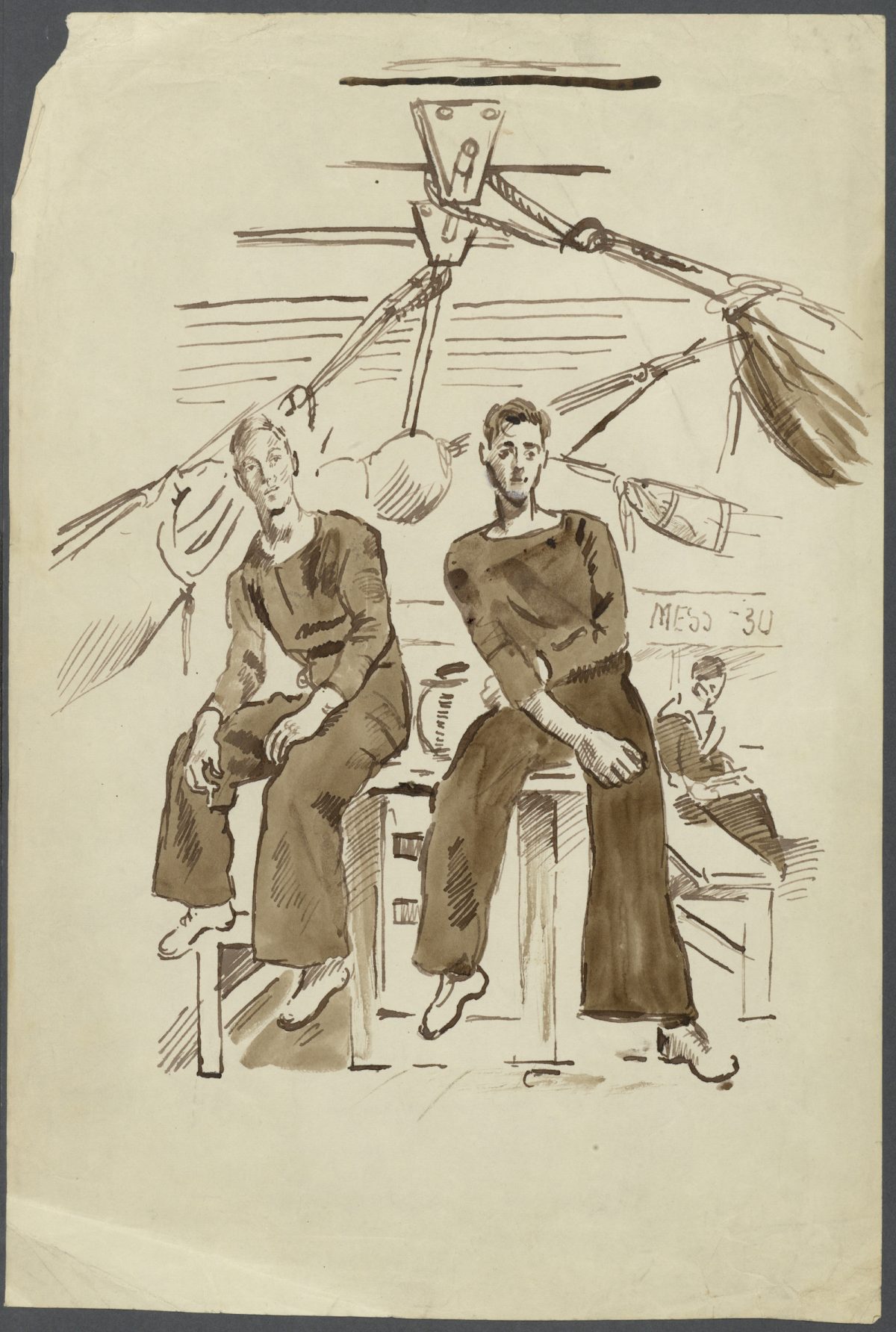

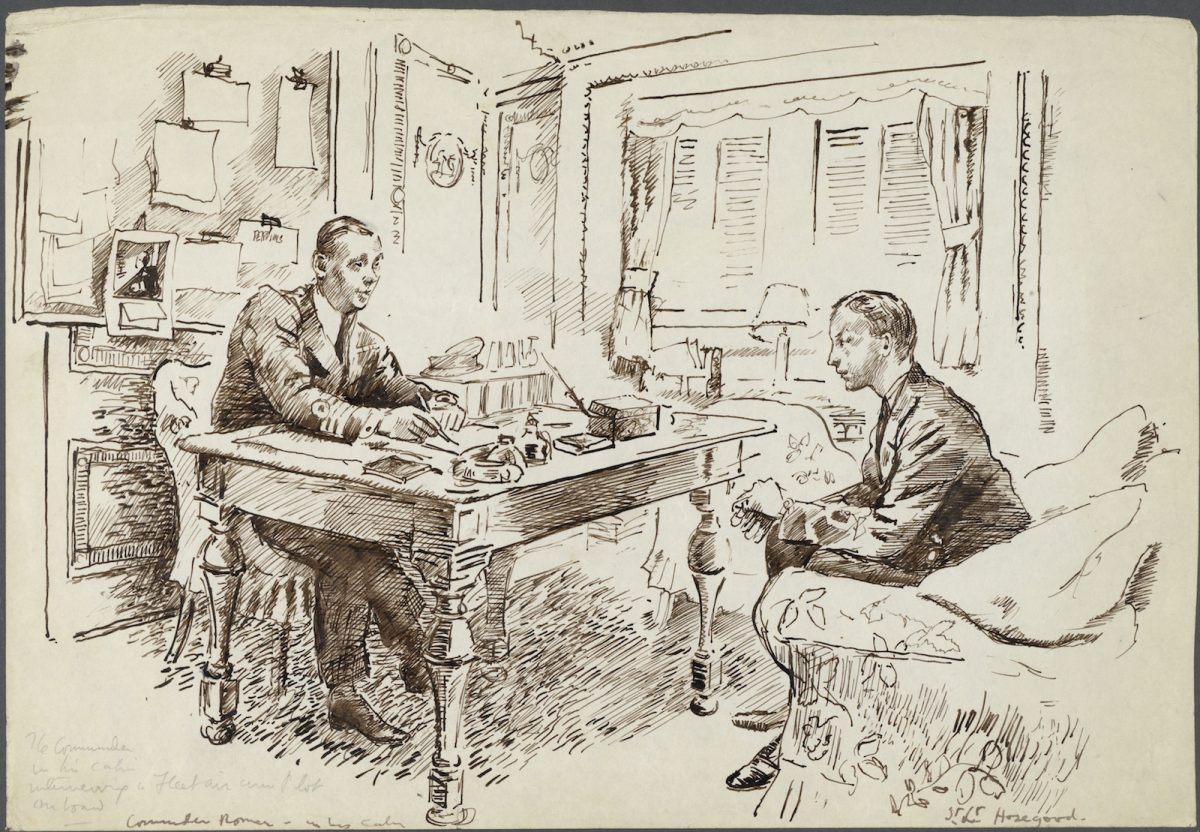

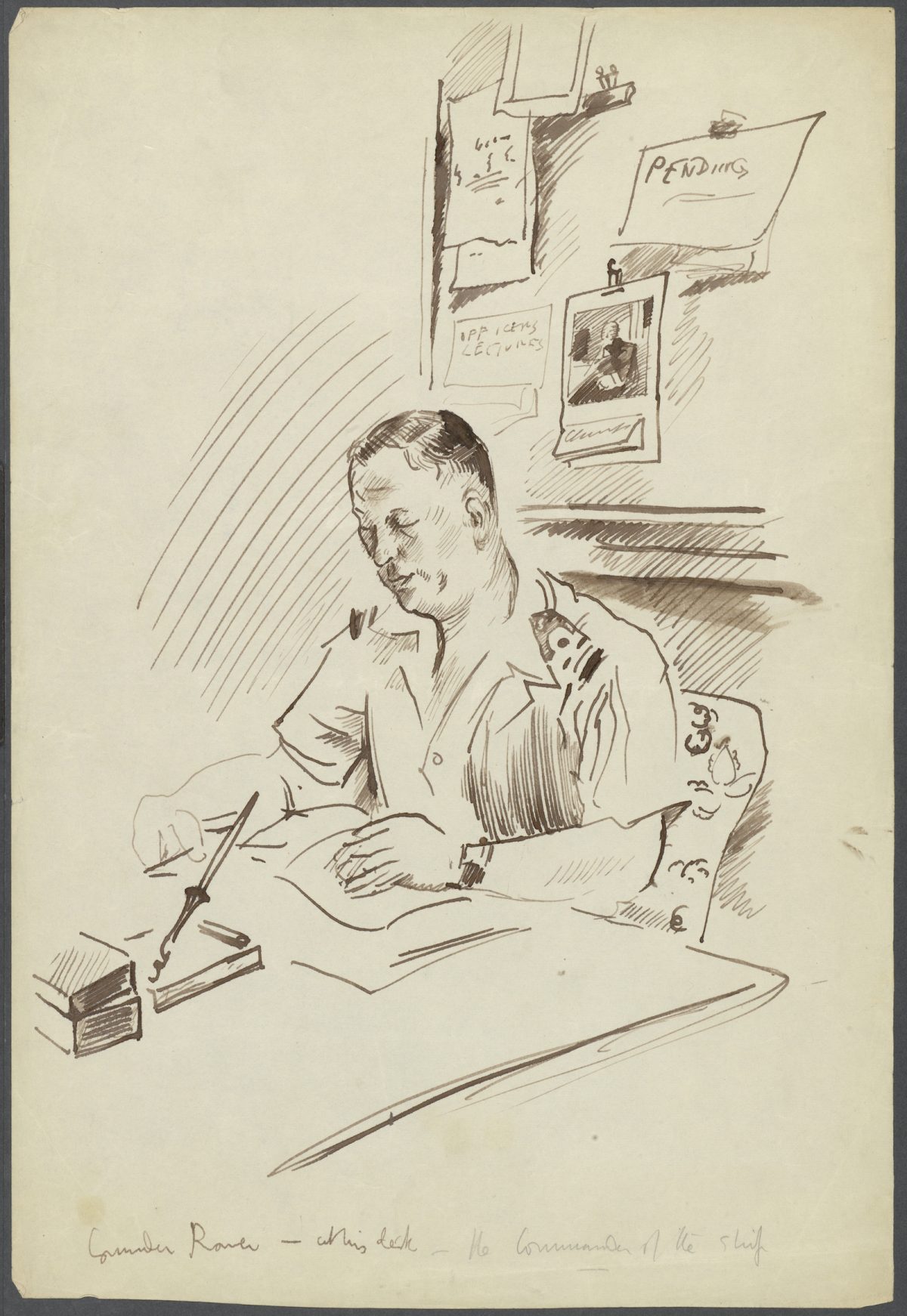

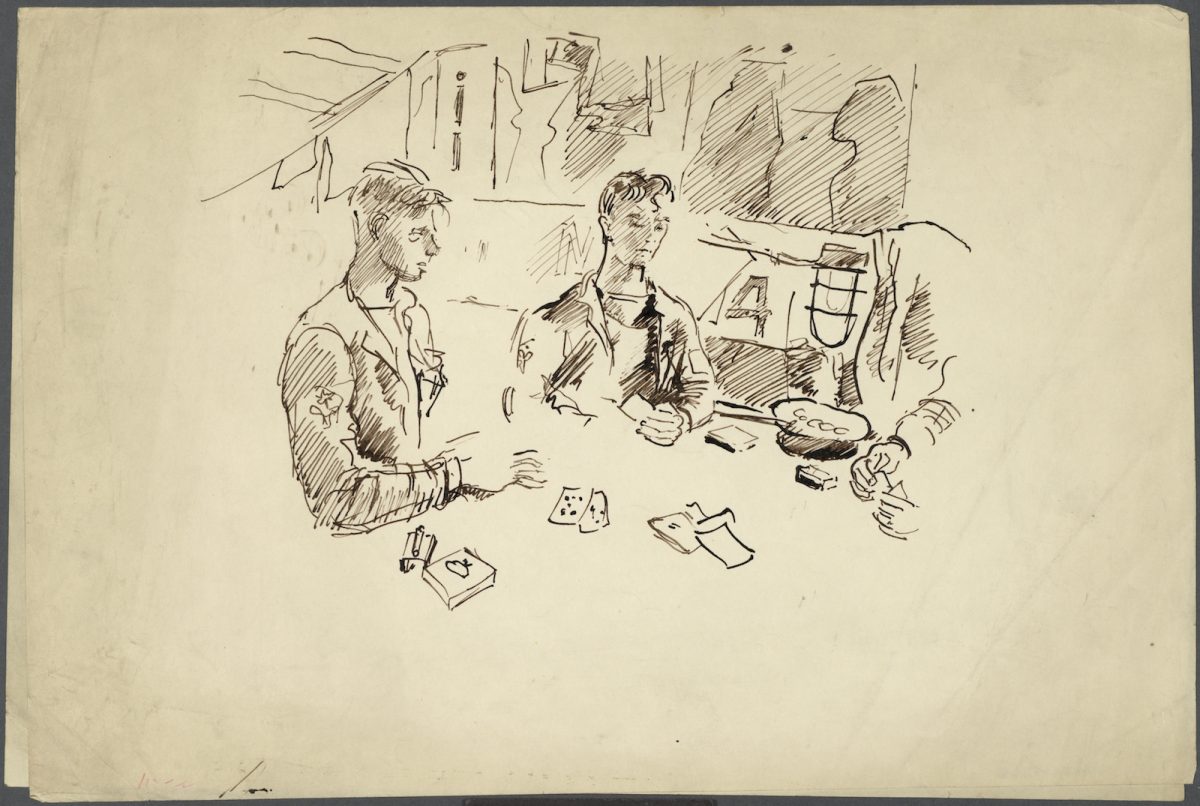

Beaton also spent time drawing pictures of the pilots, sailors, soldiers, doctors, nurses, and officers he met during the war. He drew them in sketch books or on the pages of his diary.

Two Sailors on Deck.

Commander Romer and Flight Lieutenant Hosegood.

Commander Romer.

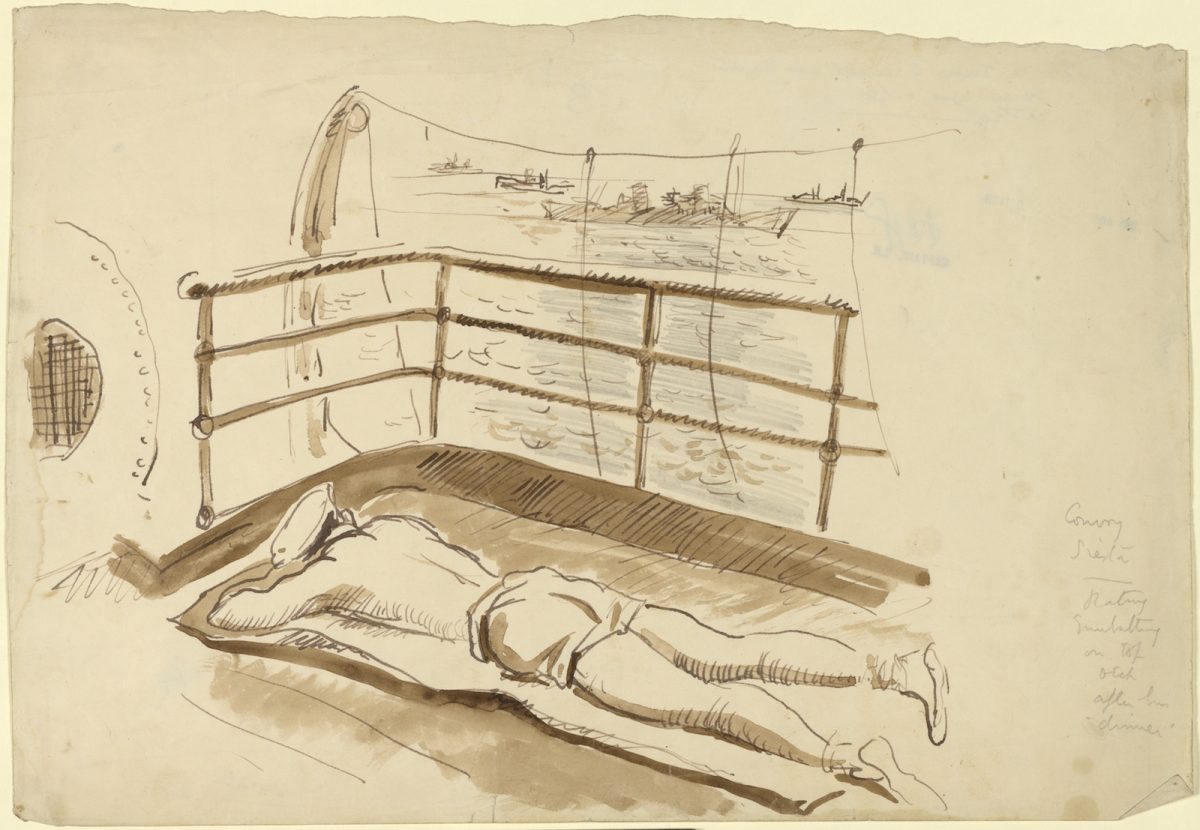

Convoy Siesta.

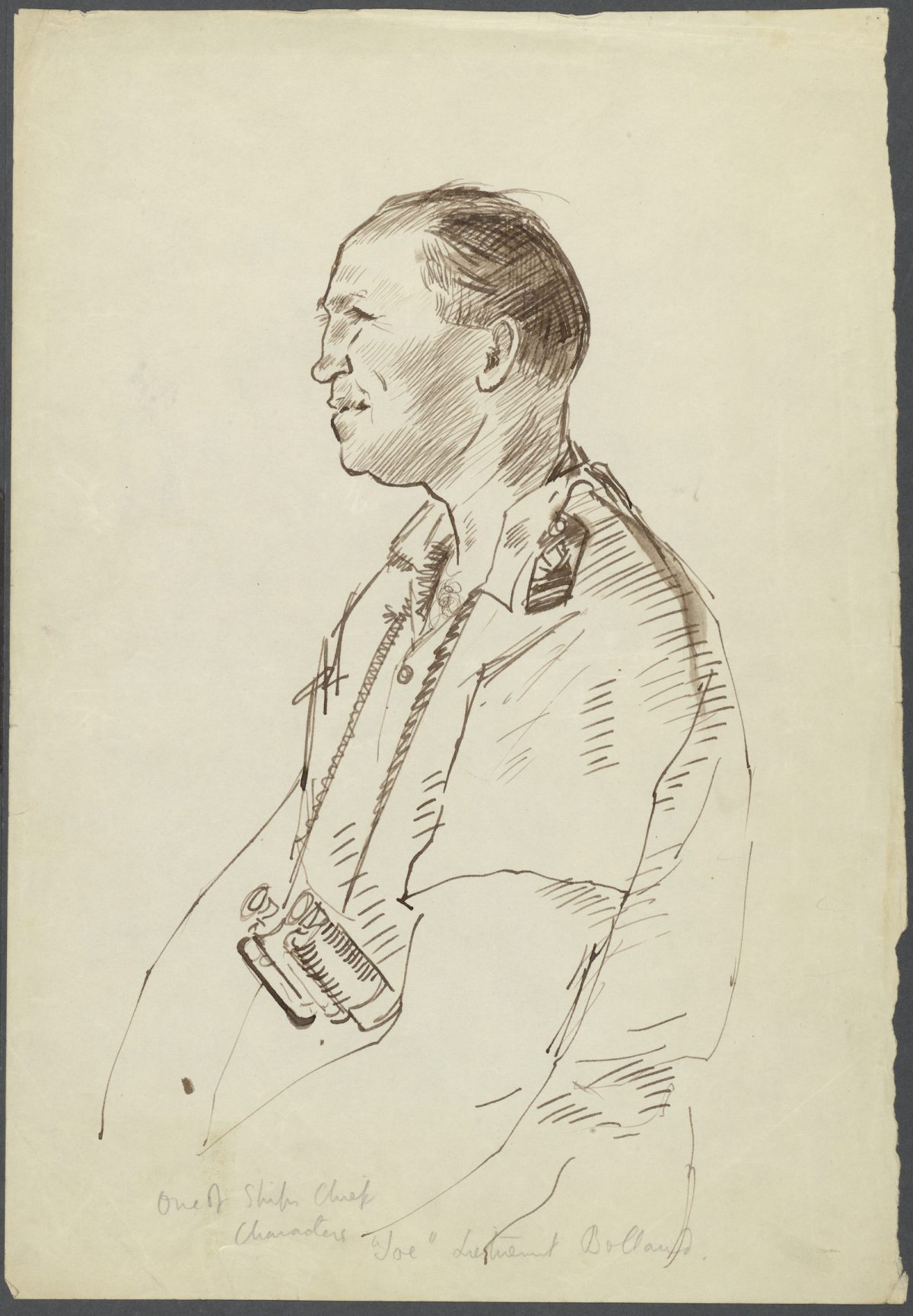

Lieutenant Bolland.

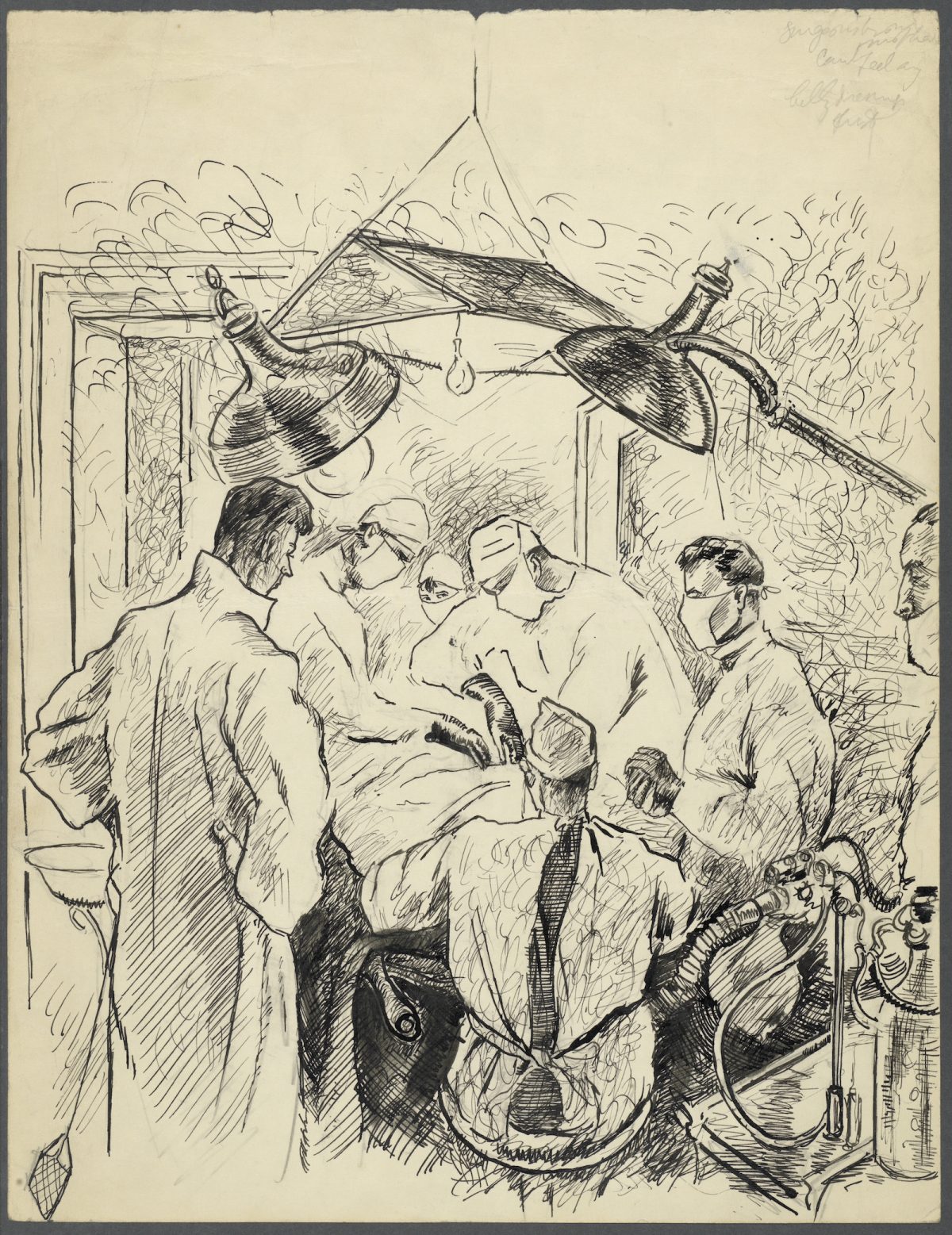

Operating Room.

About eight men in white overalls, their khaki shorts showing at the back, were pulling on rubber gloves; over their faces small squares of white linen were tied with white tape bows. My new friend was obviously disappointed that he himself was not to be performing the operation. ‘You see, we take it in turns here,’ he remarked. ‘Major Bingham is on tonight.’ The results of the X-ray photographs were handed around. The colonel showed me the negatives, which were interpreted as revealing little bits of dispersed metal, but their whereabouts could not be gauged precisely. ‘My God, you’re lucky, Beaton! This’ll be a great opportunity for you. You can take your time: it’s a big operation. It all depends where we find the metal is lodged, but it may last an hour and a half. There’s a fly!’ With a fly whisk he swotted it.

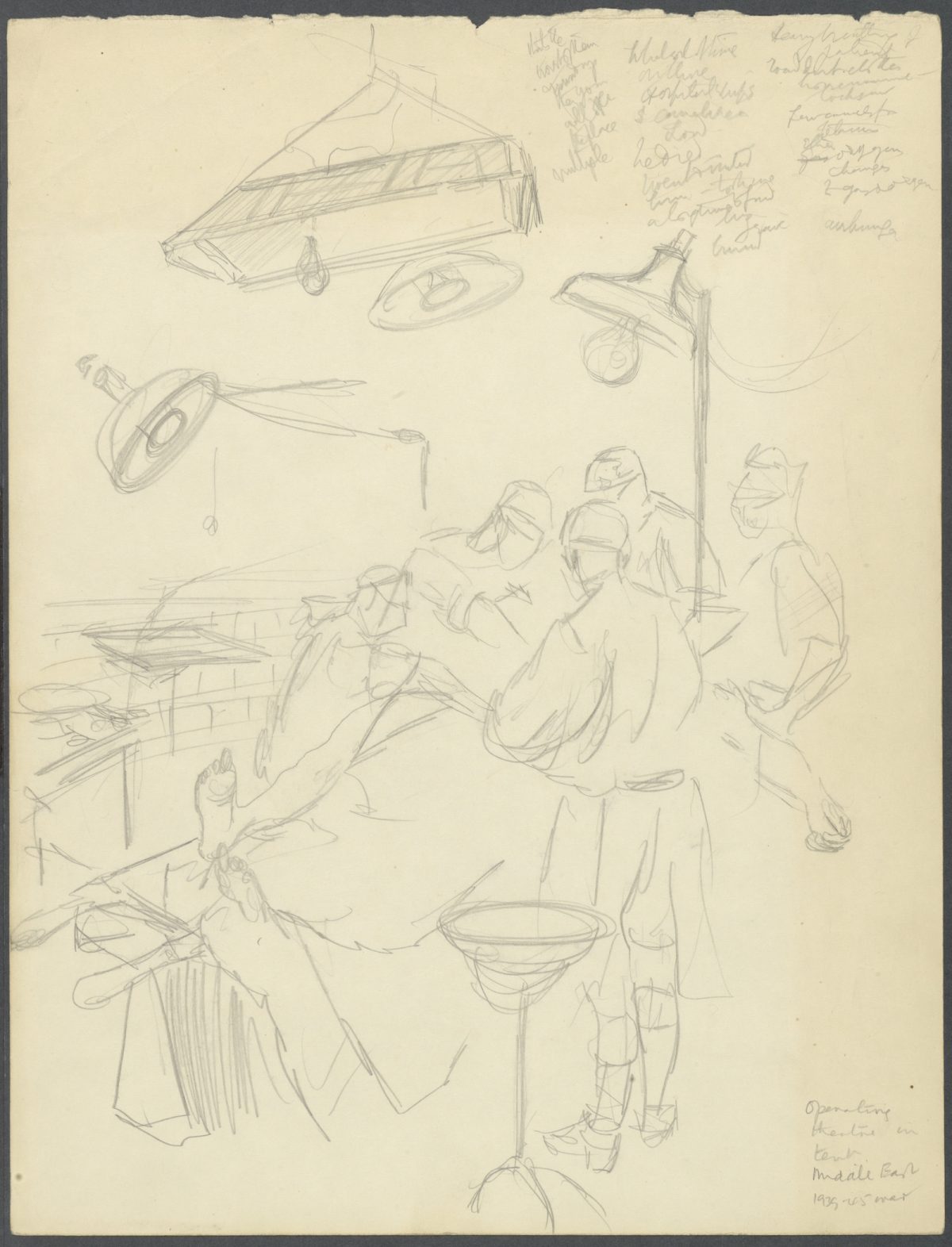

Operating Theatre in a tent in the Middle East.

The patient’s forehead began to sweat. Now he was unconscious. A nasty little safety razor began to shave the torso. A bowl containing the wisps of hair was taken away. The body was now painted orange with iodine and the operation could start. The lights were centred on the abdomen. The remaining parts were hidden beneath cloths and towels. The patient sucked air through the rubber mouthpiece which, connected by a tube, caused a glass cylinder of liquid to fill with bubbles each time he breathed out. The muffled instructions of surgeon and assistants were difficult to hear. A nurse, masked like the others, was busy with her tray of instruments, producing, one by one, the necessary knives or scissors. An assistant mopped the surgeon’s sweating brow as he slowly cut a large slit down the patient’s outer gut that was held back to reveal the intestines.

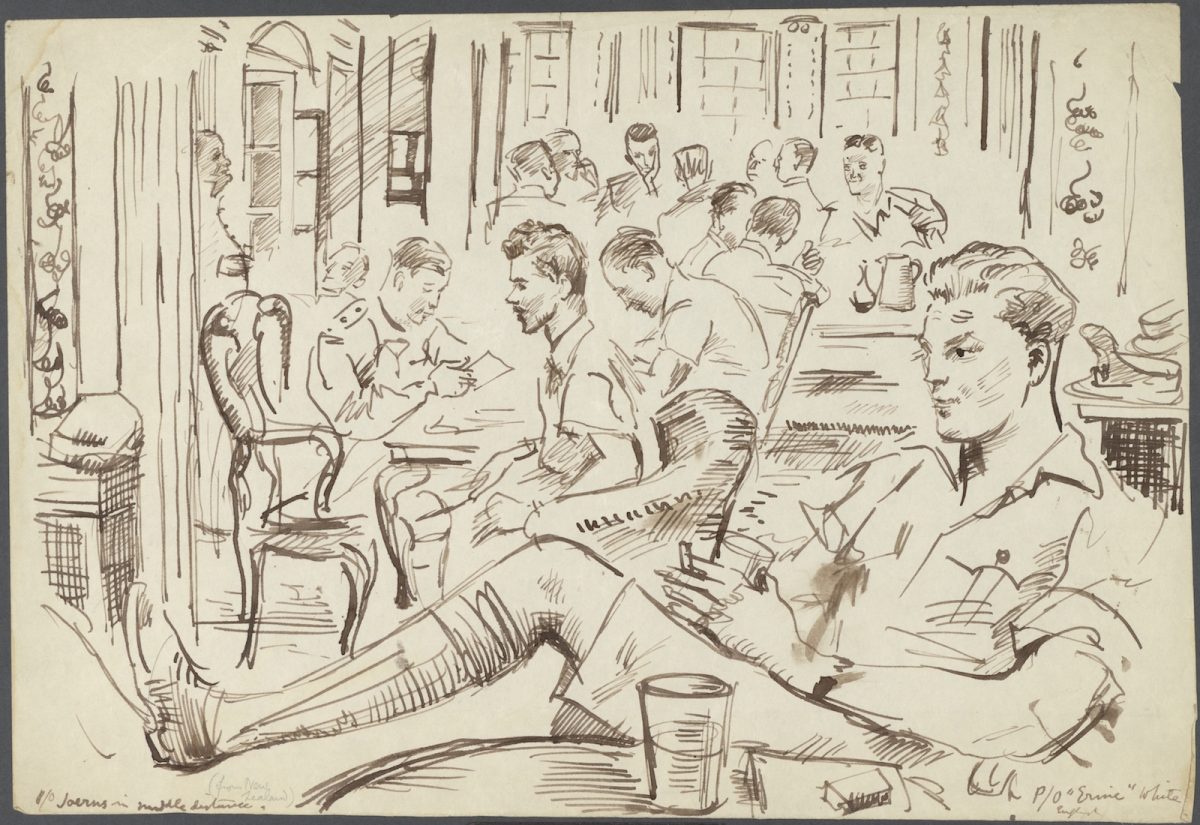

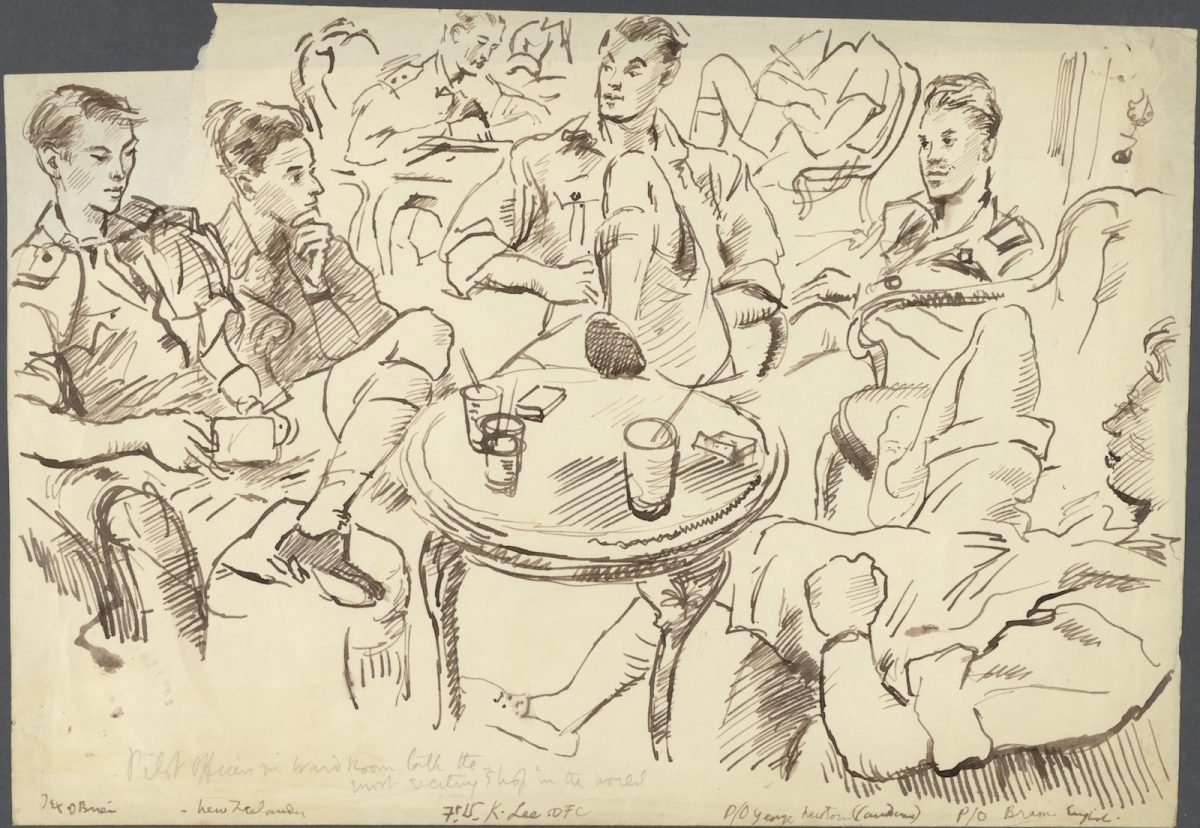

Passenger Pilot Officers in the Ward Room.

Some of the dining tables in the mess tent are adorned with wild flowers picked from the desert scrub. A certain rivalry stimulates the various messes. I heard one squadron leader, after seeing the glass display at the mess at which he had just lunched, telephone back 200 miles to his orderly, telling him that last night’s Chianti bottle must be saved and used in future on the table as a water jug.

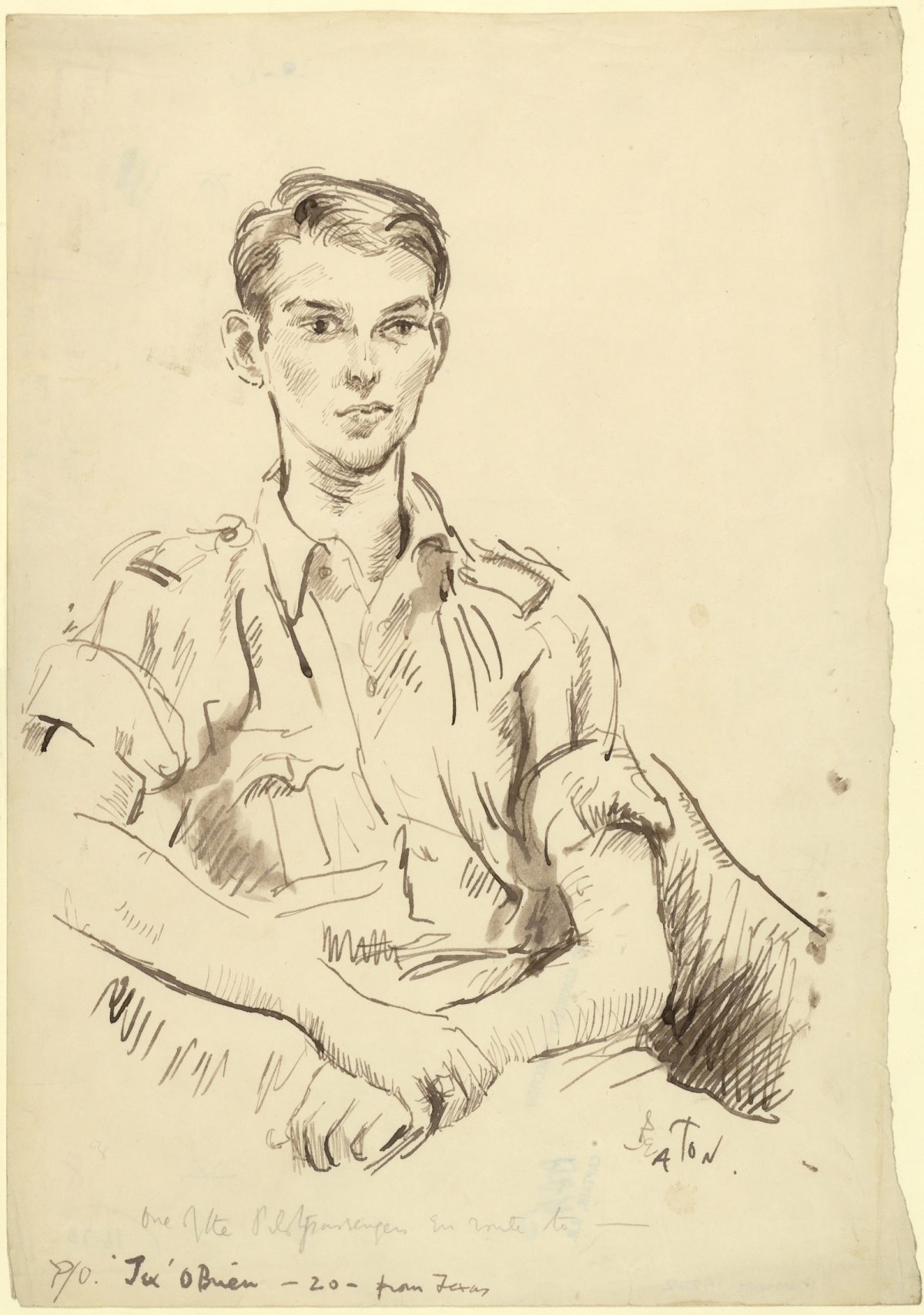

Pilot Officer ‘Tex’ O’Brien.

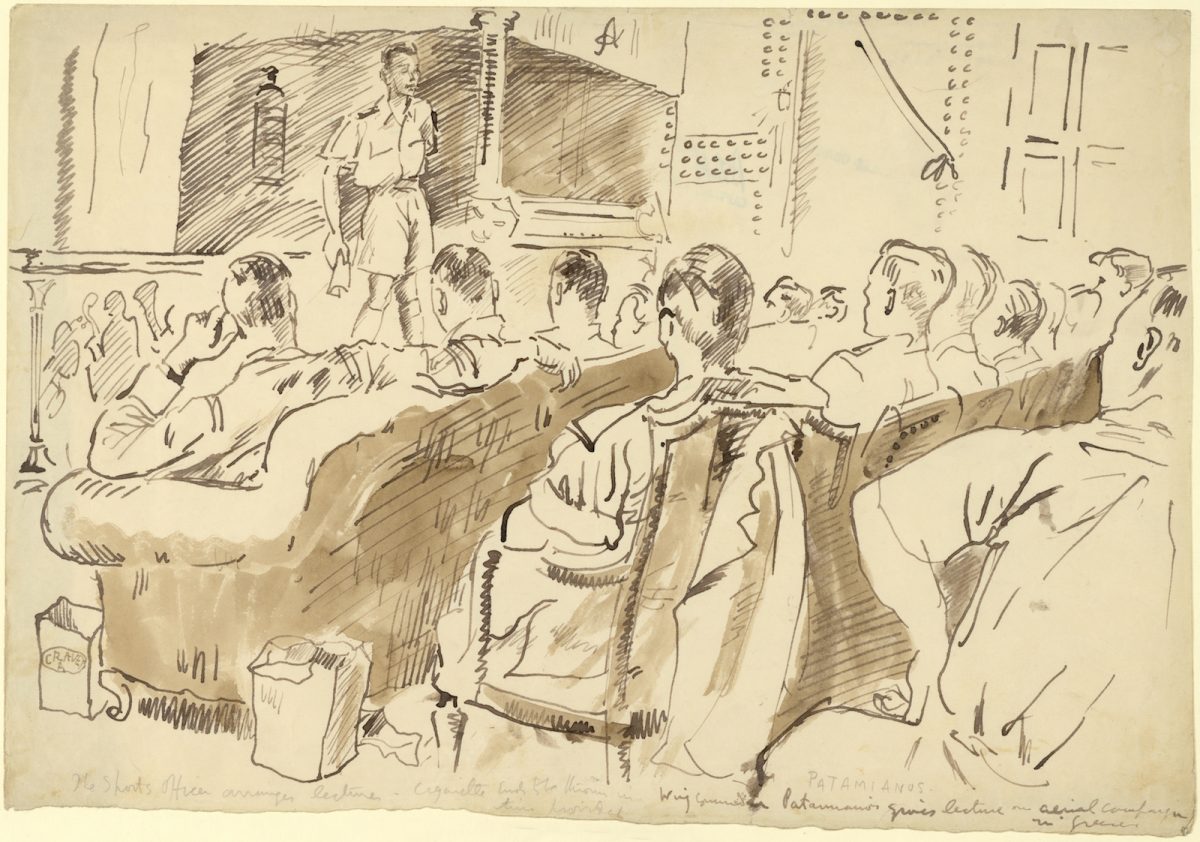

Wing Commander Patamianos lectures on aerial campaign in Greece.

Work never stops in the ‘Ops’ room. The electric bulbs burn continuously upon the maps and charts that show the progress of the latest sorties. Day and night the Met. people foretell the weather conditions of the future. In the vast dark hangars the electricians are making major repairs to every sort of aircraft. In the bomb dump armourers are loading on to trucks the explosives destined for the pressure points of the enemy’s arteries.

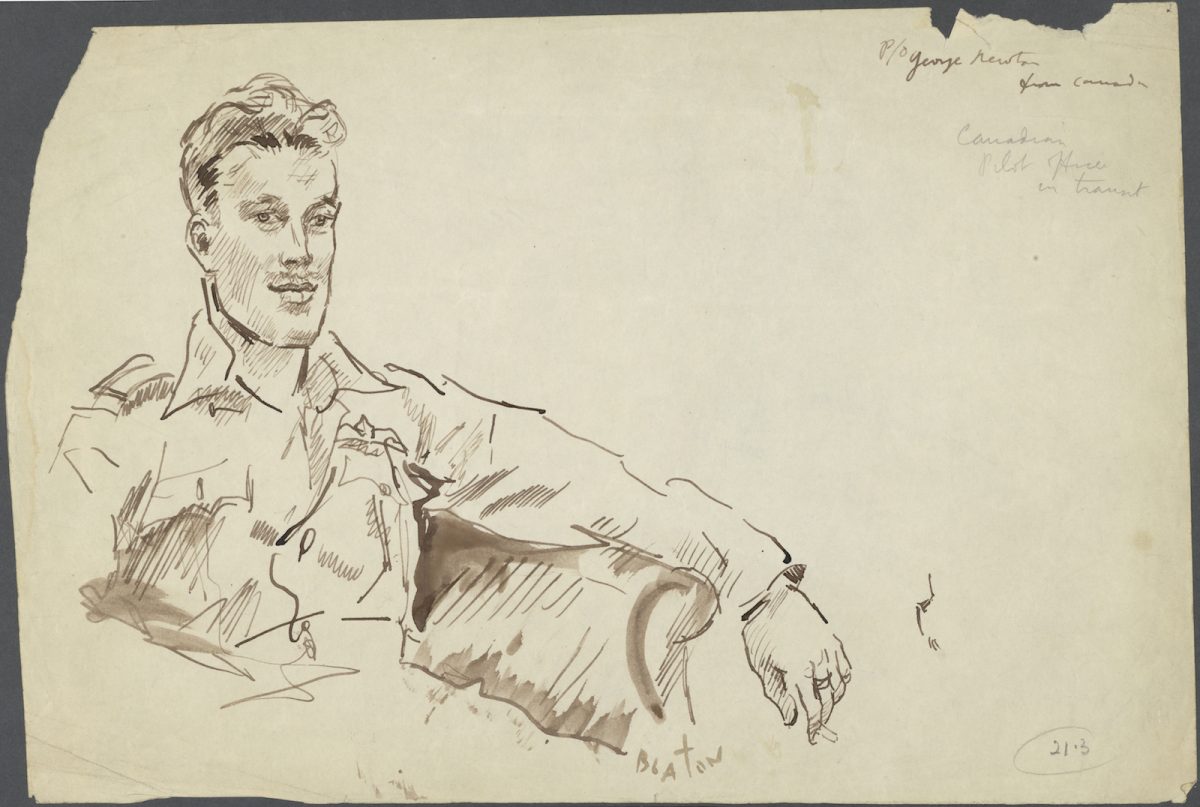

Pilot Officer George Newton from Canada.

Pilot Officers in the Ward Room.

But I now realize that feelings are controlled and smothered by a self-preservation instinct. Realization of their nearness to danger is never far removed from the minds of these youths, in spite of such easy grace of heart.

Pipe Down for Make and Mend.

One of the worst aspects of desert life is the men’s lack of reading matter. However conscientious they are about their duties, much of their time necessarily must be spent ‘hanging about being bored’. In the whole of the Middle East there is a shortage of books (such a thing as a Baedeker is nowhere available). The paper shortage is worse than it is in England, and transport cannot be spared for the printed word.

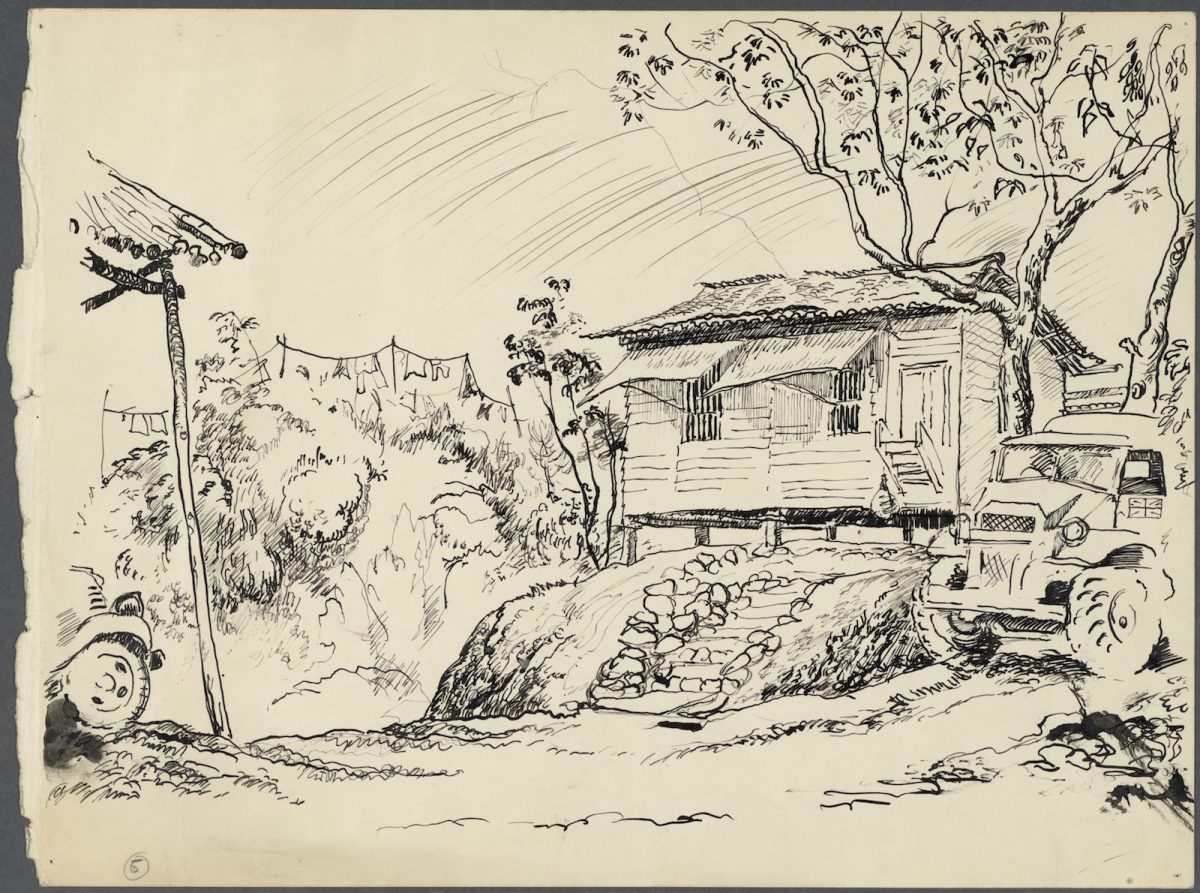

Rat-proof building British Military Mission.

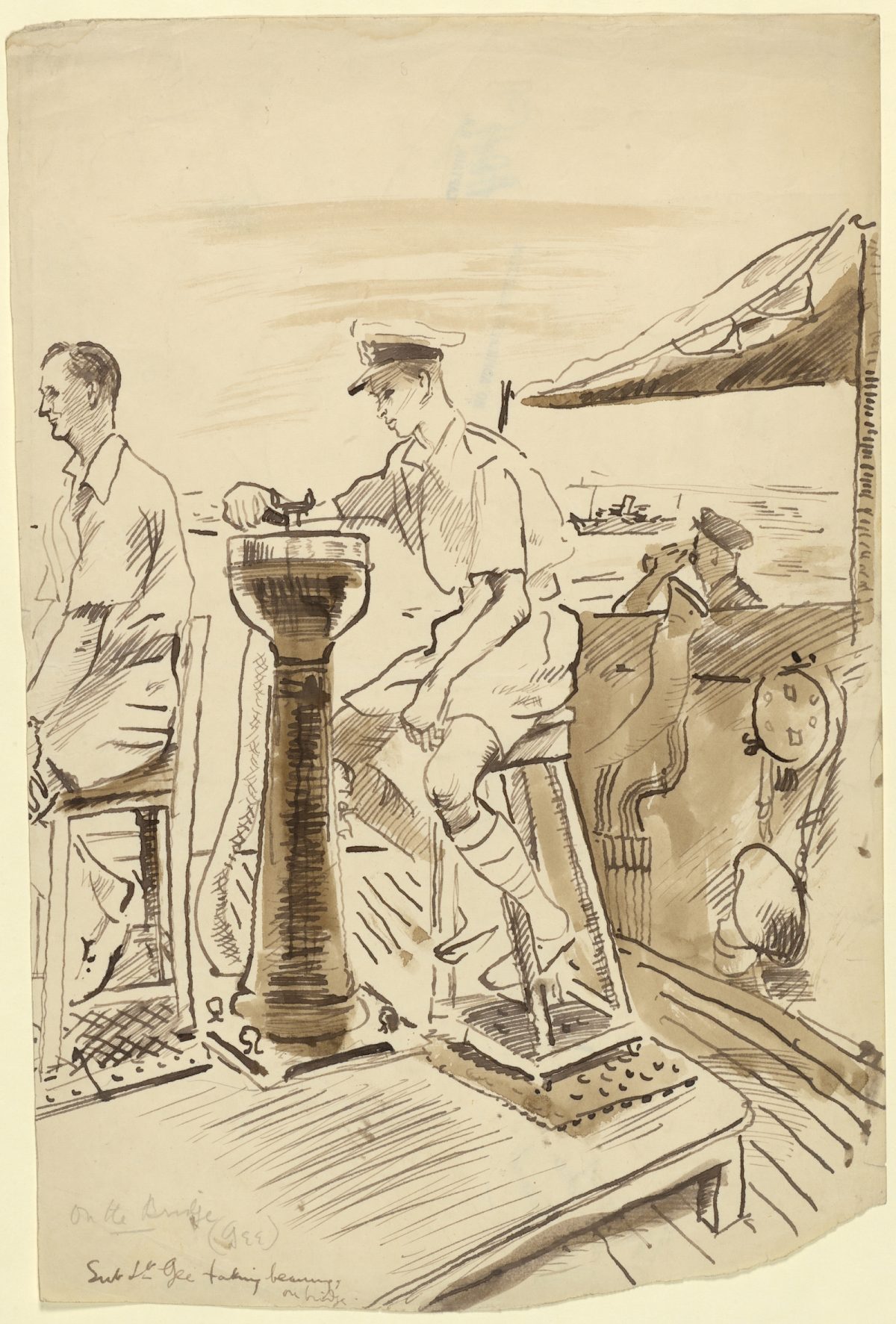

Sub-lieutenant Gee taking bearings on the Bridge.

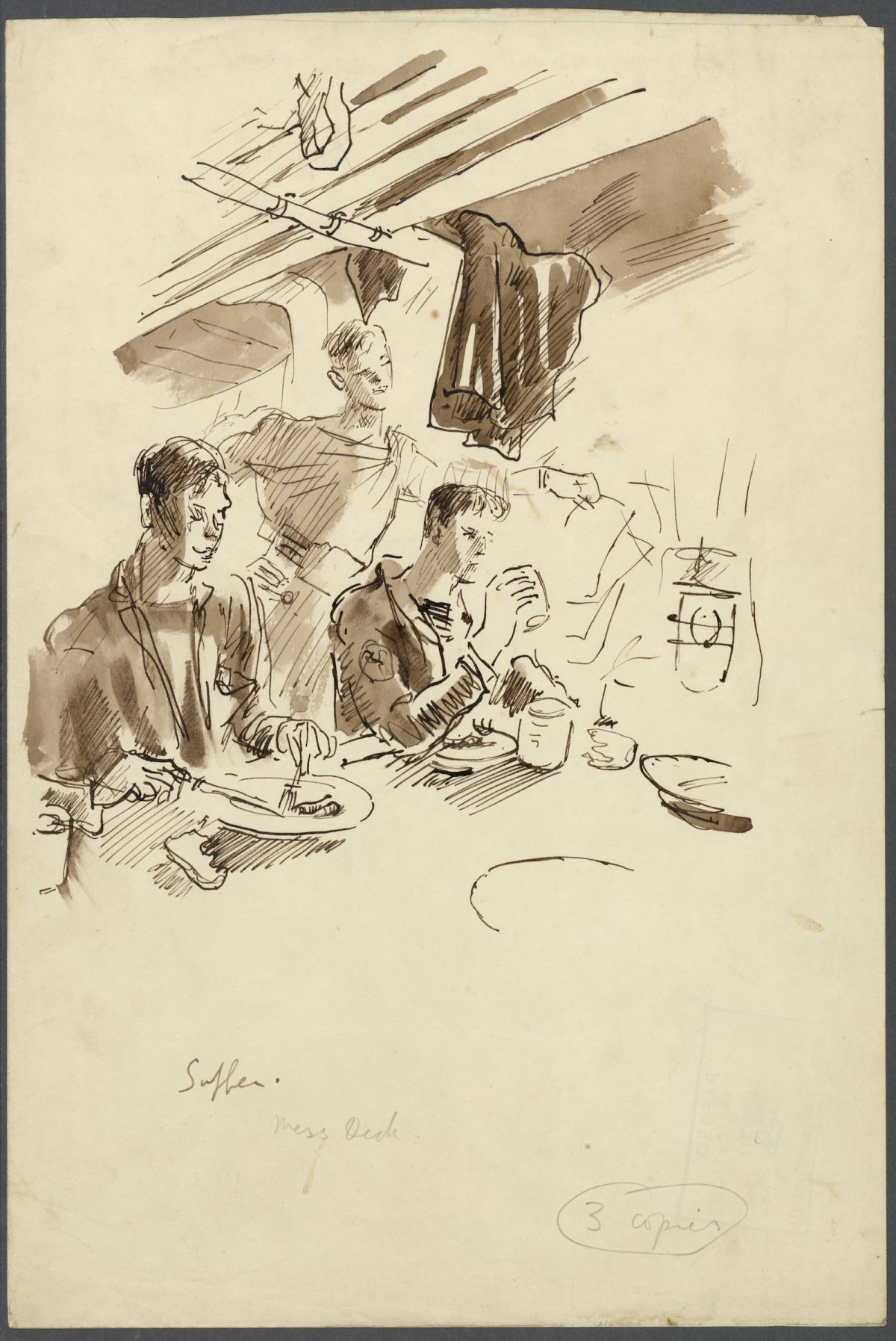

Supper Mess Deck.

The Card Game.

You can buy Cecil Beaton fine art prints in our shop.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.