“Read this book if you want to understand me” – Pablo Picasso

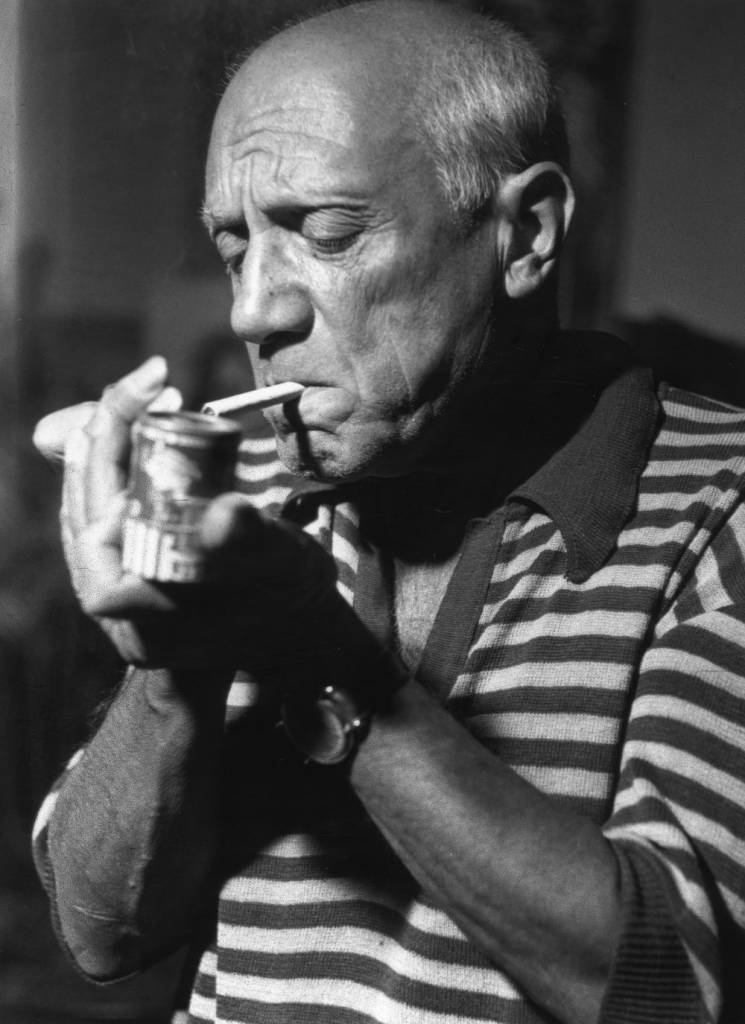

Spanish artist Pablo Picasso (1881 – 1973) lighting a cigarette. (Photo by George Stroud/Getty Images)

In the 1964 tome Conversations with Picasso, the artist considers if his inspiration arrives “by chance or by design”. His interrogator is Brassaï (born Gyula Halasz), who recorded each of his meetings and appointments with the artist whose work he photographed from 1932 to 1962. Henry Miller nicknamed Brassaï “the eye of Paris”. He also gave it a voice.

Picasso replied:

“I don’t have a clue. Ideas are simply starting points. I can rarely set them down as they come to my mind. As soon as I start to work, others well up in my pen. To know what you’re going to draw, you have to begin drawing… When I find myself facing a blank page, that’s always going through my head. What I capture in spite of myself interests me more than my own ideas…

“Matisse does a drawing, then he recopies it. He recopies it five times, ten times, each time with cleaner lines. He is persuaded that the last one, the most spare, is the best, the purest, the definitive one; and yet, usually it’s the first. When it comes to drawing, nothing is better than the first sketch.”

Spanish painter Pablo Picasso (1881 – 1973) makes a young woman wearing a bikini smile on the beach at Golfe Juan on the Riviera, Vallauris, France, 1960s. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

In 1932 Brassaï was invited to Picasso’s studio at 23 rue La Boétie, Paris. The artist wanted a photographer to record his work. The men talked. Brassaï soon realised that his conversations with the great artist were worth recording. For 30 years he returned home and wrote them on scraps of paper he stowed inside a huge vase. This extract is from Wednesday 20 October 1943:

The table, only yesterday covered with dust, is completely clean. Catalogs, brochures, books, and letters have been carefully dusted and even arranged by size into regular piles. Picasso appears, delighted with my surprise.

Picasso: I searched again all night for my flashlight. I hate it when people pilfer my things. Since I wanted to make a clean breast of things, I also attacked this whole heap of books. Maybe my flashlight got misplaced in all that. Given that opportunity, I arranged and cleaned everything.

Brassaï: What about the flashlight?

Picasso: I found it. It was upstairs in my bathroom.

Picasso has errands to do in town and goes out. Shortly thereafter, a woman enters with a package carefully tied up with string under her arm. She would like to see Picasso “in person.” She has something to show him that will undoubtedly interest him. She can wait for him all morning if necessary. When Picasso returns two hours later, she undoes the package and takes out a little picture: “M. Picasso,” she says, “allow me to present you with one of your old paintings.” And he, always rather moved to see again a work long lost from sight, looks tenderly at this little canvas.

Picasso: Yes, it’s a Picasso. It’s authentic. I painted it in Hyères where I spent the summer in 1922.

The Visitor: May I ask you to sign it, then? Owning a real Picasso without his signature is very distressing, after all! People who see it in our home may assume it’s a fake.

Picasso: People are always asking me to sign my old canvases. It’s ridiculous! In one way or another, I always marked my pictures. But there were times when I put my signature on the back of the canvas. All my works from the cubist period, until about 1914, have my name and the date on the back side of the stretcher. I know someone spread the story that in Céret, Braque and I decided not to sign our pictures anymore. But that’s just a legend! We didn’t want to sign the painting itself, that would have interfered with the composition. And even later, for that reason or for another, I sometimes marked my canvases on the back. If you don’t see my signature and the date, madam, it’s because the frame is hiding it.

The Visitor: But since the picture is by you, M. Picasso, couldn’t you do me the favor of signing it?

Picasso: No, ma’am! If I were to sign it now, I’d be committing forgery. I’d be putting my 1943 signature on a canvas painted in 1922. No, I cannot sign it, madam, I’m sorry.

Resigned, the woman wraps up her Picasso, and we continue to talk about the signature. I ask him if he purposely chose his mother’s name, “Picasso.”

circa 1950: Spanish artist Pablo Picasso (1881 – 1973) drinking in a cafe in Paris. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Picasso: My friends back in Barcelona called me by that name. It was stranger, more resonant, than “Ruiz.” And those are probably the reasons I adopted it. Do you know what appealed to me about that name? Well, it was undoubtedly the double s, which is fairly unusual in Spain. “Picasso” is of Italian origin, as you know. And the name a person bears or adopts has its importance. Can you imagine me calling myself “Ruiz”? “Pablo Ruiz”? “Diego-José Ruiz”? Or “Juan-Népomucène Ruiz”? I was given I don’t know how many names. Have you noticed, by the way, the double s in the names of Matisse, Poussin, and Le Douanier Rousseau?

And Picasso asks me if it was the double s that led me to adopt my pen name, “Brassaï.” “It’s from the name of my native city in Transylvania,” I tell him, “which contains the double s, but the sonority of the double consonant probably played some role in my choice.” Among all the letters of the alphabet, the capital S is the most graceful.

“And what other movement determines the S line? Its aesthetic efficacity has long been noted by artists; the great English painter Hogarth, in his Analysis of Beauty, even extols it as the most perfect line, calling it the ‘Line of Beauty.’ In the engravings that illustrate his book, which he himself did, he shows multiple examples of its success, in the forms of the human body, in those of a flower, in the felicitous fall of a drape, or in the outline of a piece of furniture” (René Huygue, La puissance de l’image). Another visitor arrives: the poet Georges Hugnet. He has just discovered one of Picasso’s old gouaches and intends to buy it. “It’s one of your finest gouaches: a popular fête with men and women dancers. It’s being offered to me for 150,000 francs.”

Picasso: That’s not so expensive! I remember it well. I painted it in Juan-les-Pins. It was a fête on the Iles de Lérins, on Sainte-Marguerite. Old people were there. They were dancing almost naked. Is that the one? Yes, you may buy it. You’ll be getting a good deal.

Georges Hugnet leaves to acquire the gouache. I show Picasso my twenty “arrondissements”: a series of nudes done ten years earlier, nudes made completely of round forms, curvatures, arrondissements. Picasso sets them out on the floor.

Spanish painter Pablo Picasso (1881 – 1973) and a young woman watch a bullfight, Spain, 1960s. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Brassaï: What excited me was the vase, musical instrument, fruit aspect of the female body. That characteristic was captured in the art of the Cyclades: the woman was transposed into a sort of violin. And I was surprised to see how much the largest fruit, from the “maritime coconut palm,” resembles the female posterior and lower abdomen.

Picasso: That enormous coconut you’re talking about is the strangest fruit I’ve ever seen. Have you seen the one I own? Someone gave it to me one day as a gift. I’ll go get it for you.

And Picasso brings back the enormous nut. Mine is in its natural state, with granulated skin and hair. His has been polished and shows off the grain of an exotic wood.

Picasso: That was a good idea of yours to chop up the female body that way. The details are always exciting.

Then he looks at a few nudes, metamorphosed into landscapes. The outline that circles the body and simultaneously traces a relief of hills and valleys interests him intensely. You go directly from the sinuous lines of the female body to an undulating landscape. Picasso notices that in some photos the texture of “goose flesh” suggests the skin of an orange, the network formed by sea waves seen from afar, or the granulations of stone. One of the attractions of the photo is that it fosters such associations, such visual metaphors. And we talk about stones: sandstone, granite, marble.

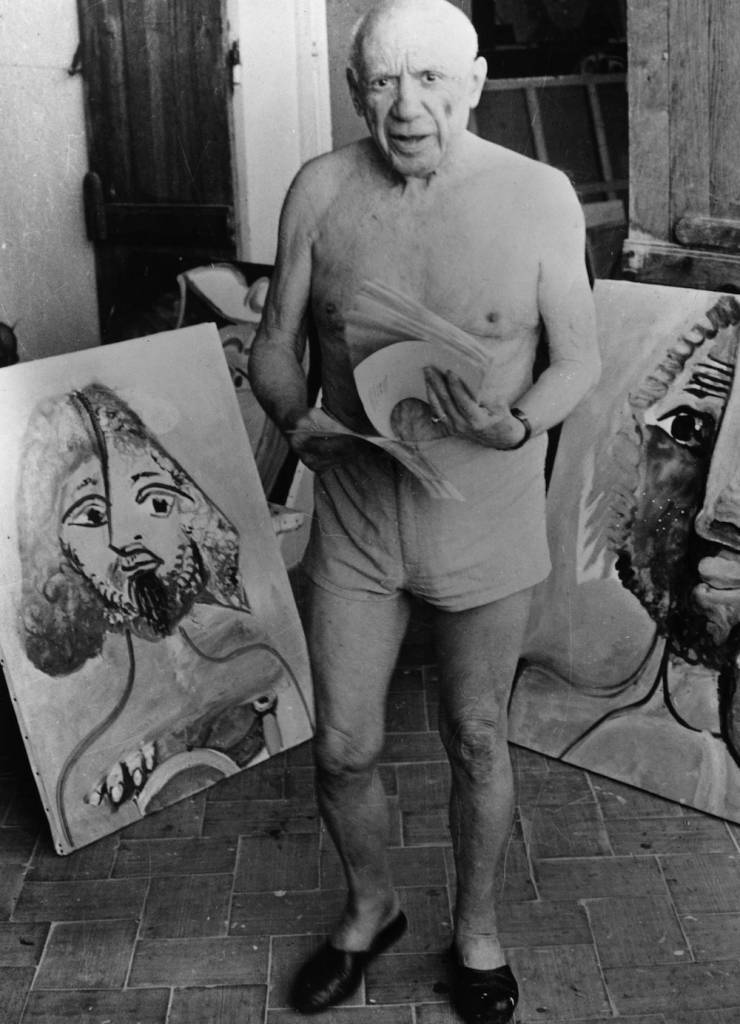

15th February 1973: Spanish artist Pablo Picasso (1881 – 1973) with some of his paintings at Mougins Cote D’Azur in the south of France. (Photo by Central Press/Getty Images)

Picasso: It seems strange to me that someone thought of making marble statues. I understand how you could see something in the root of a tree, a crack in the wall, in an eroded stone or pebble. But marble? It comes off in blocks and doesn’t evoke any image. It does not inspire. How could Michelangelo have seen his David in a block of marble? Man began to make images only because he discovered them nearly formed around him, already within reach. He saw them in a bone, in the bumps of a cave, in a piece of wood. One form suggested a woman to him, another a buffalo, still another the head of a monster.

We have returned to prehistoric times.

Brassaï: A few years ago, I was in the valley of Les Eyzies in Dordogne. I wanted to see cave art at the source. One thing surprised me: every generation, totally unaware of the ones that preceded it, nevertheless organized the cave in the same way, at a distance of thousands of years. You always find the “kitchen” in the same place.

Picasso: Nothing extraordinary about that! Man doesn’t change. He keeps his habits. Instinctively, all those people found the same corner for their kitchen. To build a city, don’t men choose the same sites? Under cities you always find other cities; other churches under churches, and other houses under houses. Races and religions may have changed, but the marketplace, the living quarters, pilgrimage sites, places of worship, have remained the same. Venus is replaced by the Virgin, but the same life goes on.

Spanish-born artist Pablo Picasso (1881 – 1973) holds up a statuette of a fighting bull, presented to him by toreadors in appreciation of his art, in the stands at a bullfight at Vallauris, France, 11th August 1955. On the left is Jacqueline Roque (1927 – 1986), who later married Picasso. On the right is French author, artist and filmmaker Jean Cocteau (1889 – 1963). (Photo by Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Brassaï: In the lower strata of the valley of Les Eyzies, excavation archaeologists had the brilliant idea of preserving a cross-section four to five meters high, with layers built up over millennia. It’s like a mille-feuille. In every layer, the “tenants” left their visiting cards: fragments of bone, teeth, flints. In a single glance, you can take in thousands of years of history. It’s very moving.

Picasso: And you know what’s responsible? It’s dust! The earth doesn’t have a housekeeper to do the dusting. And the dust that falls on it every day remains there. Everything that’s come down to us from the past has been conserved by dust. Right here, look at these piles, in a few weeks a thick layer of dust has formed. On rue La Boétie, in some of my rooms—do you remember?—my things were already beginning to disappear, buried in dust. You know what? I always forbade everyone to clean my studios, dust them, not only for fear they would disturb my things, but especially because I always counted on the protection of dust. It’s my ally. I always let it settle where it likes. It’s like a layer of protection. When there’s dust missing here or there, it’s because someone has touched my things. I see immediately someone has been there. And it’s because I live constantly with dust, in dust, that I prefer to wear gray suits, the only color on which it leaves no trace.

Brassaï: It takes a thousand years of dust to make a one-meter layer. The Roman Empire is buried two or three meters underground. In Rome, Paris, and Arles, the empire is in our cellars. Prehistoric layers are even thicker. We know something about primitive man—you’re right—only because of the “protection” of dust.

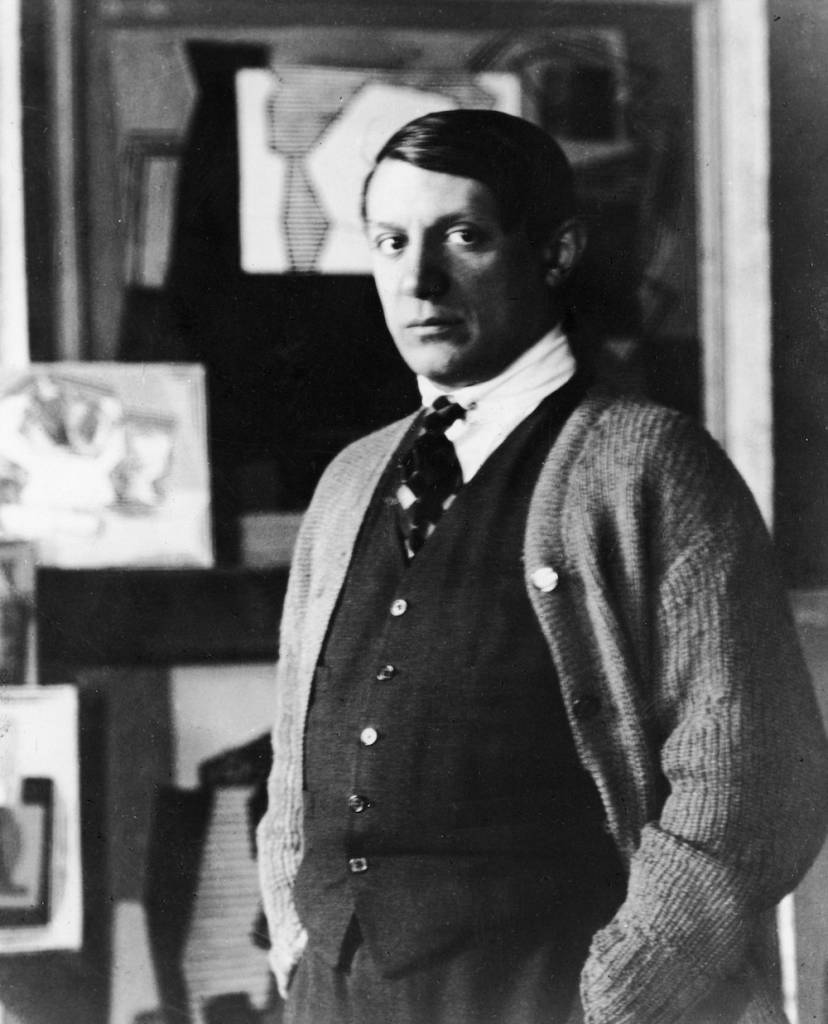

Portrait of Spanish painter Pablo Picasso (1881 – 1973) standing in his studio, 1920s. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Picasso: In reality, we know very little. What is conserved in the ground? Stone, bronze, ivory, bone, sometimes pottery. Never wood objects, no fabric or skins. That completely skews our notions about primitive man. I don’t think I’m wrong when I say that the most beautiful objects of the “stone age” were made of skin, fabric, and especially wood. The “stone age” ought to be called the “wood age.” How many African statues are made of stone, bone, or ivory? Maybe one in a thousand! And prehistoric man had no more ivory at his disposal than African tribes. Maybe even less. He must have had thousands of wooden fetishes, all gone now.

Brassaï: Picasso, do you know what the earth preserves best? Greco-Roman coins. I’ve followed the excavations in Saint-Rémy, where a Greek village is being uncovered. With every shovelful of dirt a coin appears.

Picasso: It’s insane how many Roman coins are being found! It’s as if all Romans had holes in their pockets. They sowed coins wherever they went. Even in the fields. Maybe to grow money . . .

Brassaï: With excavations, I always have the impression they’re breaking a mold to take out a sculpture. In Pompeii, it was Vesuvius that did the casting. Houses, men, animals were instantly caught in that boiling gangue. There is something deeply moving about those convulsed bodies, captured at the moment of death. I saw them in their glass cages in Pompeii and Naples.

Picasso: Dali was really obsessed with the idea of such monstrous castings, of that instantaneous end to all life by a cataclysm. He talked to me about a casting of the place de l’Opéra, with the opera building, the Café de la Paix, the high-class chicks, the cars, the passersby, the cops, the newspaper kiosks, the girls selling flowers, the streetlights, the clock still marking the time. Imagine it in plaster or bronze, life-size. What a nightmare! If I could do that, I’d choose Saint-Germain-des-Prés, with the Café de Flore, the Brasserie Lipp, the Deux-Magots, Jean-Paul Sartre, the waiters Jean and Pascal, M. Boubal, the cat, and the blonde cashier. What a marvelous, monstrous casting that would make.

circa 1948: Spanish artist Pablo Picasso, (1881 – 1973), at work in his Mougins pottery works, France. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

We’ll end with Picasso’s word on being committed utterly to your calling:

When you have something to say, to express, any submission becomes unbearable in the long run. One must have the courage of one’s vocation and the courage to make a living from one’s vocation. The “second career” is an illusion! I was often broke too, and I always resisted any temptation to live any other way than from my painting… In the beginning, I did not sell at a high price, but I sold. My drawings, my canvases went. That’s what counts.

Such dedication gives you the space to dream and have ideas – to let the dust settle…

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.