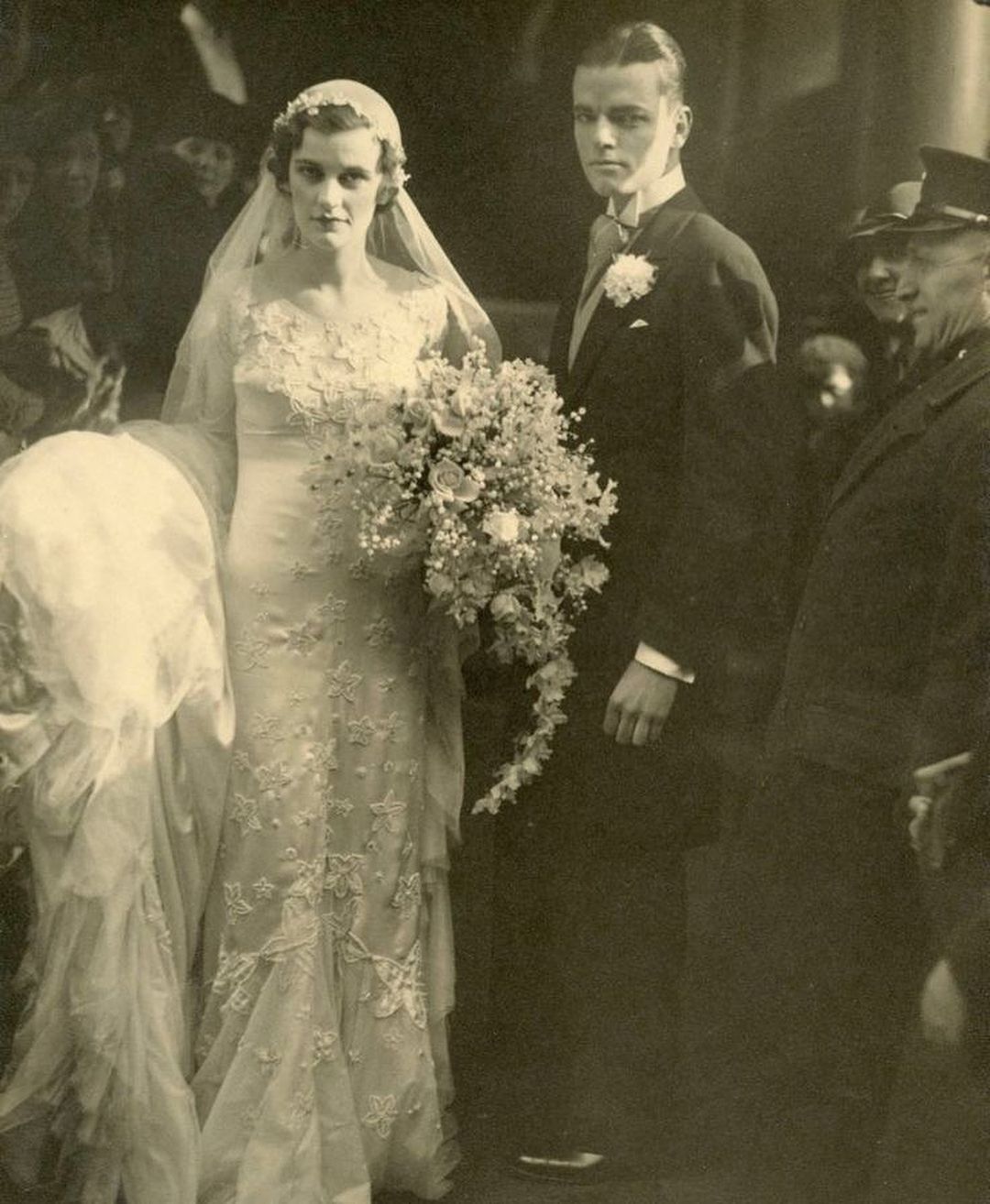

In 1933 the Mayfair socialite Margaret Whigham was fêted like a film star. When, that year, she married the dashing, rich amateur golfer Charles Sweeny at Brompton Oratory in Knightsbridge over 3,000 onlookers turned up to gawp. The Times, the next day, reported that many had been desperate for a closer look:

No sooner had the bride procession moved up the aisle than the swing doors on either side of the main entrance were besieged by women who, using elbows and umbrellas freely, forced their way into the church, and for a moment stood swaying in a solid mass, completely cutting off the means of entry of guests who arrived late.

Three years previously, in 1930, at the age of seventeen and a half she became Miss Whigham became debutante of the season, and according to Bystander magazine ‘Margaret Whigham was quite the smartest jeune fille’ in London. She would write years later: ‘I wore make-up, nail polish, and was extremely well-dressed. I was out every night, and nobody dressed like I did.’ Theoretically she was chaperoned, but in reality she went where she liked when she liked. The family chauffeur was always on hand to take her from party to party, and then back home again. Margaret remembered that she used to see one man for dinner, plead tiredness and go home, only then to go out with another young man to the Embassy Club or the Café de Paris. At closing hour she and her partner would then ‘float on’ to late nightclubs such as Kate Meyrick’s Silver Slipper. Her father’s only rule was that she absolutely must be dressed for the family breakfast at nine. With rumours that her father employed a press agent, Margaret was never out of the newspapers and it has been said that she singlehandedly invented what came to be known as the ‘deb-ballyhoo industry’.

Margaret Whigham, at the ‘Jewels of Empire’ Ball at Brook House, Park Lane, 1930

After courting and rejecting both Prince Aly Khan and the 7th Earl of Warwick (Not long before the break-up Lady Warwick, called Margaret’s mother to say, ‘If you love your daughter, don’t let her marry my son. He’s a liar, he’s ill-mannered, and he picks his nose.’) Margaret married Charles Sweeny in February 1933 and was by now very famous indeed, in fact so famous she was even mentioned in a popular song of the time – a very popular song.

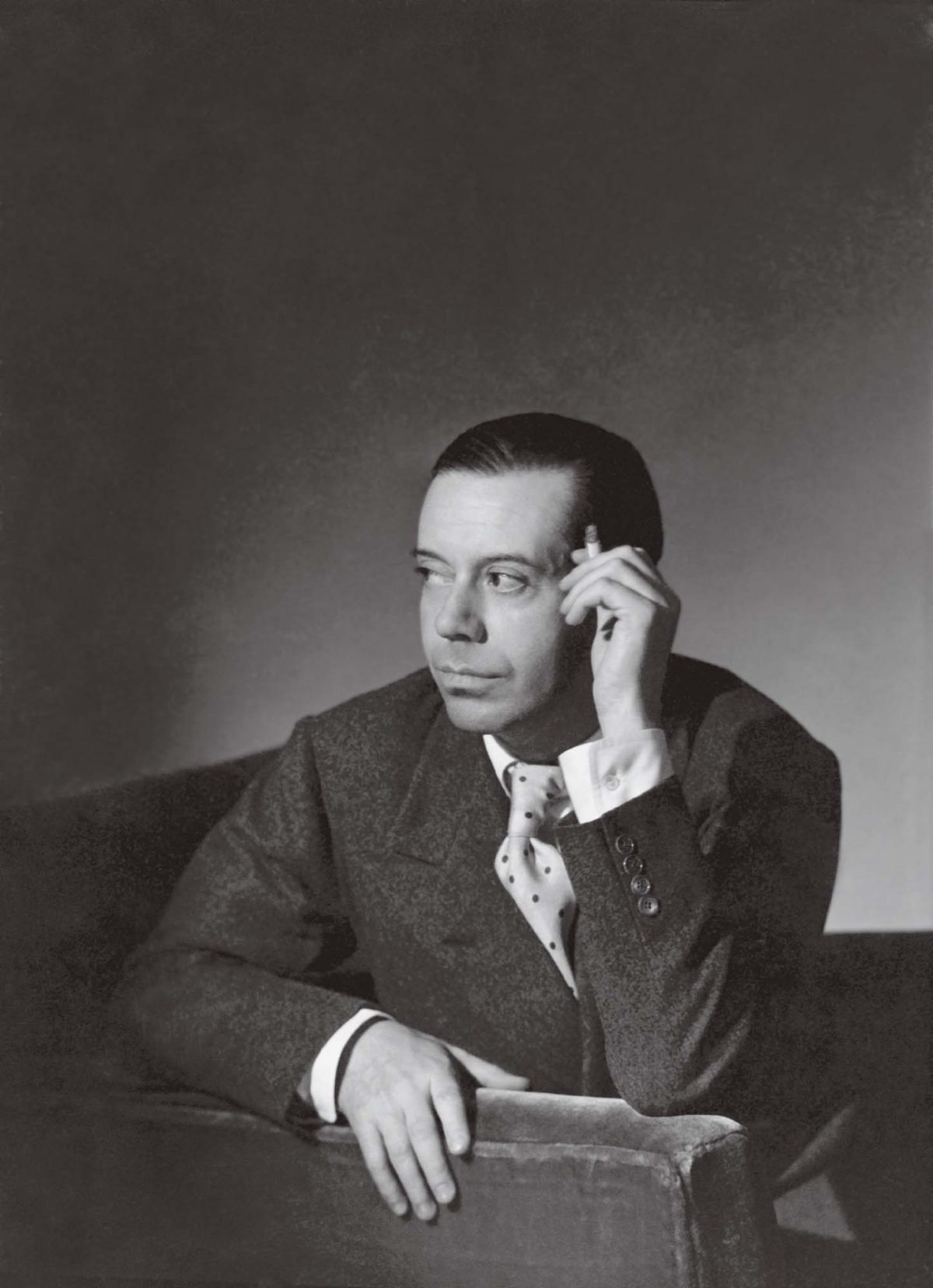

In most articles, obituaries and biographies written about Margaret Sweeny/Whigham (later to be the Duchess of Argyll) including her autobiography where the fact is mentioned on the back cover, it was noted that she was so celebrated that Cole Porter included her as a superlative in one of his famous list songs. ‘I had wealth, I had good looks,’ Margaret would later write, ‘As a young woman I had been constantly photographed, written about, flattered, admired, included in the Ten Best-Dressed Women in the World list, and mentioned (as Mrs Sweeny) by Cole Porter in the words of his hit song “You’re the Top”.’

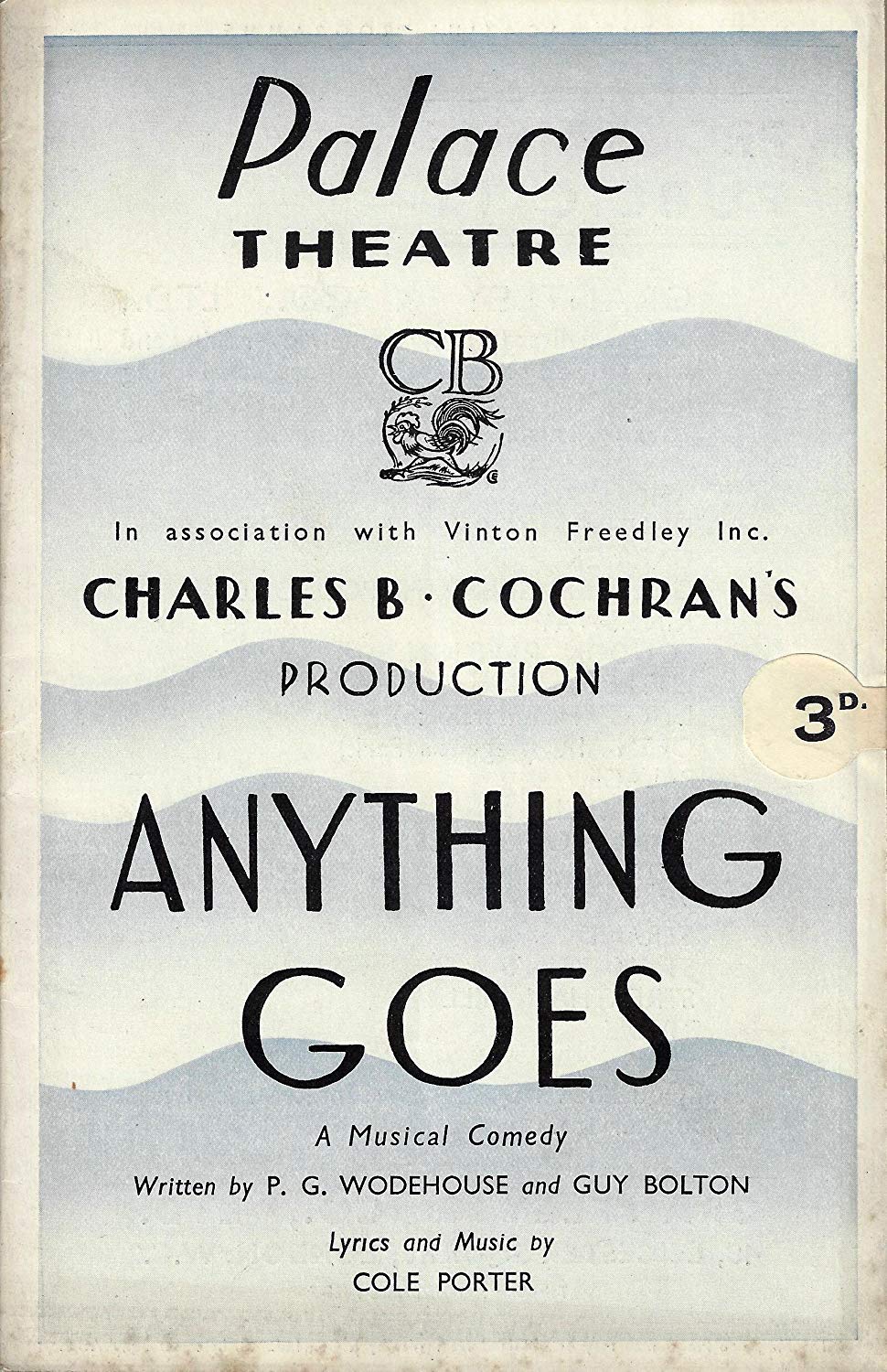

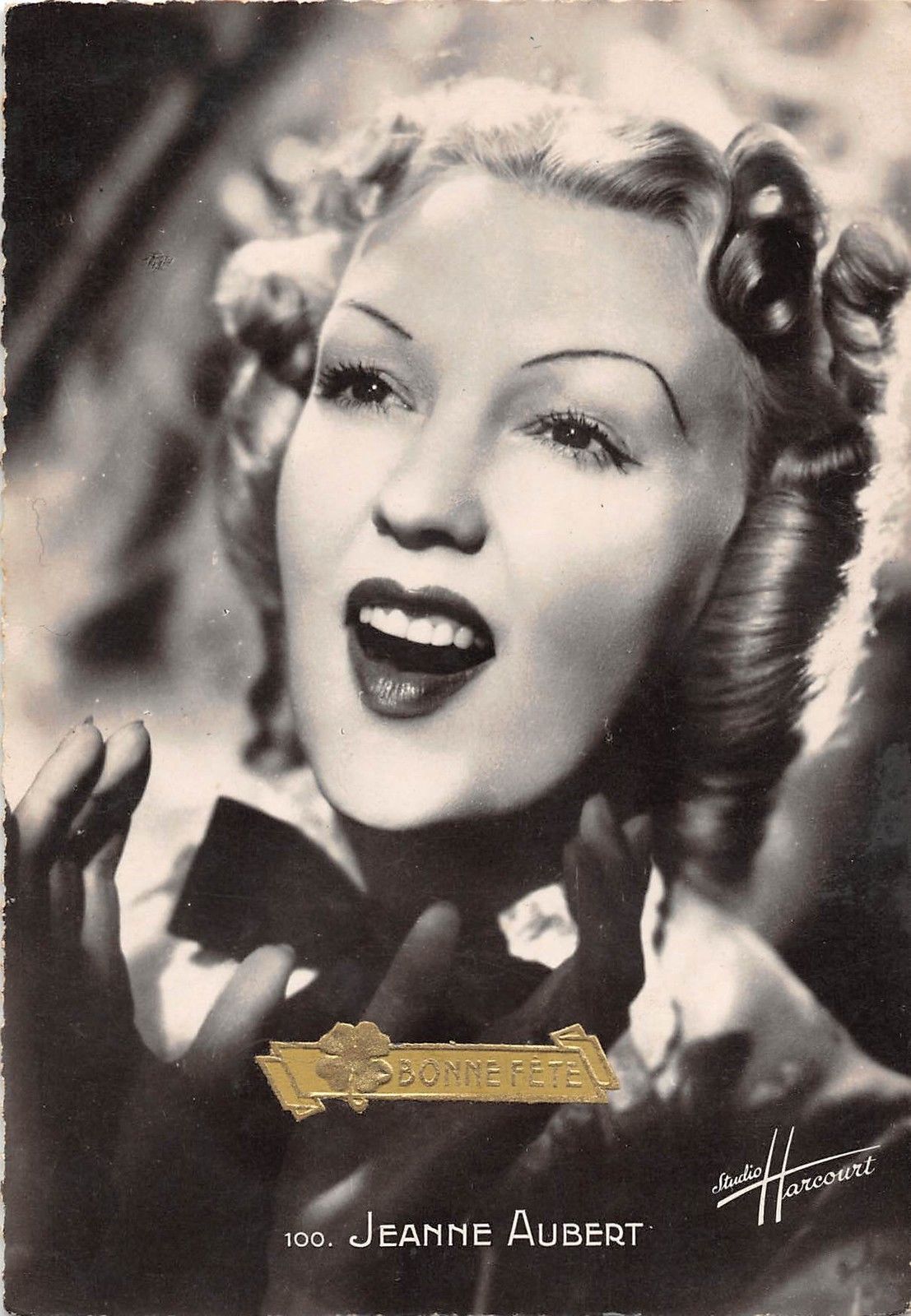

Along with the title song and ‘I Get A Kick Out of You’, ‘You’re the Top’ was one of the hit songs from Cole Porter’s musical Anything Goes, which opened in London at the Palace Theatre on 15 June 1935. Produced by the impresario C. B. Cochran, it starred the French actress Jeanne Aubert in the role of Reno La Grange, Sydney Howard as Moonface Martin and Jack Whiting as Billy Crocker. Although the music and lyrics were by Porter, the original book of the show was a collaborative effort between Guy Bolton and P. G. Wodehouse (albeit heavily revised by Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse). Before the revisions the musical was to be more of a satire on Hollywood from where Bolton and Wodehouse had recently returned. Wodehouse once joked that it was ‘an era when only a man of exceptional ability and determination could keep from getting signed up by a Hollywood studio in some capacity or other’. Wodehouse wrote to his friend William (Bill) Townend in August 1934:

I’m having a devil of a time with this musical comedy Guy Bolton and I are writing. I can’t get hold of Guy or the composer, so have been plugging along by myself. Still, Guy says he will be here on Saturday. What has become of the composer, heaven knows. Last heard of at Heidelberg and probably one of the unnamed three hundred shot by Hitler.

Wodehouse was possibly referring to Porter’s homosexuality in the letter. Many of the 300 SA Brownshirts Hitler had murdered during the Night of the Long Knives the previous month were killed for ‘abnormal proclivities’. Wodehouse, incidentally, was often critical of Porter’s lyric writing. In 1961, he wrote to Guy Bolton enclosing some updated lyrics for a new production of Anything Goes:

The trouble with Cole is that he has no power of self-criticism. He just bungs down anything whether it makes sense or not just because he has thought of what he feels is a good rhyme. I have rewritten the verse because Cole’s verse seemed to me absolute drivel … I always feel about Cole’s lyrics that he sang them to Elsa Maxwell and Noël Coward in a studio stinking of gin and they said, ‘Oh, Cole, darling it’s just too marvellous.’

Benny Green once wrote that Wodehouse’s ‘brilliant and immensely influential career as a Broadway lyricist is entirely forgotten today except by people like Ira Gershwin and Richard Rodgers, who readily acknowledge him as the pioneer of the colloquial song lyric’. And it was Wodehouse’s revised lyrics written especially for the British audiences and not Cole Porter’s that used Mrs Sweeny in the song. ‘It was flattering,’ she later wrote, ‘to be included with the Louvre Museum, a Shakespeare sonnet, Mickey Mouse, the smile on the Mona Lisa, Garbo’s salary, a dress by Patou and the other things Cole Porter considered “the top”.’ She was less keen, however, that Mrs Sweeny was rhymed with Mussolini … Cole Porter’s original lyrics, used in the original Broadway version and usually still used today, were:

You’re an O’Neill drama, You’re Whistler’s mama!

Wodehouse’s version, and the one sung by Jeanne Aubert on the London stage in 1935, was:

You’re Mussolini, You’re Mrs Sweeny.

The use of Mussolini as an example of being ‘the top’ seems more than a little odd these days. Not helped with the knowledge that seven years after Ethel Merman first sang the song on Broadway Wodehouse was taken prisoner by the invading Germans at his house in Le Touquet in France and subsequently interned for a year. The English writer then made six broadcasts to the US from a German radio station in Berlin. He wrote to a friend at the time,

I’m living here in the Adlon Hotel in a suite on the third floor – and a very nice one, too! They took me round and showed me Berlin. We went to the Olympic Stadium and Potsdam and back by the steamer on the Wannsee.

The communication betrayed his casual attitude to his plight and sounded more like a jolly postcard home than a letter of a guest of the Nazis in wartime Berlin. The six talks were comic and apolitical, but the broadcasts over enemy radio prompted anger in Britain, along with a threat of prosecution. He was seen by many as a traitor and a Nazi propagandist. A front-page article in the Daily Mirror stated:

P.G. Wodehouse has cracked his worst joke. And the laugh is against his own country. IT’S BITTER LAUGHTER … He lived luxuriously because Britain laughed with him, but … Wodehouse was not ready to share her suffering. He hadn’t the guts (or was it that he hadn’t the wish?) even to stick it out in the internment camp.

In Performing Flea, a 1953 collection of letters, Wodehouse wrote:

Of course I ought to have had the sense to see that it was a loony thing to do to use the German radio for even the most harmless stuff, but I didn’t. I suppose prison life saps the intellect.

He was shocked by the controversy he had caused, however, and never returned to England again. From 1947 until his death he lived in the US, taking dual British-American citizenship in 1955.

November 1922: Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini (1883 – 1945). (Photo by Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

In the early 1930s Mussolini was seen by many in a surprisingly good light. The Italian fascist actually visited London, albeit for a rather brief stay, in December 1922 for a conference on German reparations. The Manchester Guardian, in an article published two months before his trip, wrote:

The subtle Italian mind adores a man of action, a man of elemental force. Mussolini, ‘The Thunderer,’ whose words become deeds as they drop from his mouth, has swept most of young Italy off their feet, and for the time being holds them in the hollow of his hand.

The man of elemental force arrived at Victoria station on 9 December and was met by about fifty black-shirted supporters. The Manchester Guardian, like many newspapers of the time, found the uniformed fascists faintly amusing. The correspondent thought all the energetic marching about was to do with the cold, and was worried that the thin ‘black shirt (accompanied by a black tie, some war medals, and a black cloth cap shaped like a fez with a tassel and cord) looked poor comfort for eleven o’clock on a slightly foggy December night’. He then described how the Blackshirts started singing the Italian Fascist marching song ‘Giovinezza’. This was all repeated half an hour later outside Claridge’s Hotel, where Mussolini and his entourage were staying. In fact, during his entire stay and wherever he went, organised groups of Blackshirts greeted him and sang the same fascist marching song again and again.

During their stay at Claridge’s there was an unseemly row, reported in the press, when the Italian delegation accused their French counterparts of being allocated better rooms. No one quite knew what to make of the young Italian leader. In London he wore spats, a butterfly collar with a top hat and badly pressed striped trousers. The aristocratic British Foreign Secretary, Lord Curzon, remarked: ‘He is really quite absurd.’ Most people were also surprised by Mussolini’s height (he was only 5 feet 6 inches). The next day, Mussolini and his party, all wearing Fascist party badges, were received at Buckingham Palace by the king. Later, the Italians all drove to the Cenotaph in Whitehall, where Signor Mussolini laid a wreath of remembrance at the foot of the monument. Finally, they visited the Italian Fascist HQ at 25 Noel Street. At one point during the trip Mussolini missed a press conference because he was sleeping with a prostitute back at the hotel. During his stay he complained incessantly about the fog, which he insisted penetrated his clothes, his bedroom and even his suitcases. When he returned to Italy he swore that he would never return to England, and he never did.

Nine years later, while he was touring Europe, Gandhi (also mentioned in ‘You’re the Top incidentally) accepted an invitation to visit Mussolini in late 1931 in Rome. He even reviewed a black-shirted Fascist youth honour guard during his stay. Regarding his visit with Il Duce, Gandhi wrote in a letter to a friend:

Many of his reforms attract me. He seems to have done much for the peasant class. I admit an iron hand is there. But as violence is the basis of Western society, Mussolini’s reforms deserve an impartial study … My own fundamental objection is that these reforms are compulsory. But it is the same in all democratic institutions.

Gandhi would also hail Mussolini as ‘one of the great statesmen of our time’. George Bernard Shaw once declared of the Italian dictator, ‘Socialists should be delighted to find at last a socialist who speaks and thinks as responsible rulers do.’ Winston Churchill called Mussolini ‘the greatest living legislator’ and once wrote to his wife in 1926: ‘No doubt he is one of the most wonderful men of our time.’ Clementine responded a few days, quoting a friend: ‘It is better to read about a world figure than to live under his rule.’

The London production of Anything Goes that featured the song ‘You’re the Top’.

Jeanne Aubert

The London transfer of Porter’s musical Anything Goes opened on 14 June 1935 to generally very favourable reviews, although one pointed out that due to Jeanne Aubert’s French accent it was difficult to hear the words she was singing – Mrs Sweeny/Mussolini or otherwise.

However, if the audiences didn’t raise a collective eyebrow to the Mussolini reference initially, some must have done four months after the premiere when the fascist dictator, keen to create an Italian version of the British Empire, invaded Ethiopia, then known as Abyssinia. The invasion is often seen as one of the episodes that paved the way for the Second World War, and demonstrated the ineffectiveness and weakness of the League of Nations, of which Italy and Ethiopia were both members. During the Ethiopian conflict, the Italians made substantial illegal use of mustard gas, sprayed directly from above like an ‘insecticide’, including on civilians and Red Cross camps and ambulances. It was Mussolini himself who authorised the use of the gas.

Ethiopians saluting the ‘Great White Father’ Mussolini.

Benito Mussolini, King Victor Emmanuel III, and high officials of the Italian military photographed in Ethiopia in 1936

The Italians also instituted forced labour camps, installed public gallows, killed hostages, and mutilated the corpses of their enemies. Captured guerrillas were even killed by being thrown out of planes mid-flight. Italian troops had themselves photographed next to dead Ethiopian soldiers hanging from the gallows or chests full of detached heads. Even during the Abyssinian conflict, however, the Lord Chamberlain’s Office, the censors of the London stage, didn’t look kindly on any political satire about European leaders, even fascist dictators. They judged Eric Barker’s burlesque of the League of Nations (‘Intrigue of Nations’) at the Windmill Theatre as ‘needlessly barging in on a delicate situation’, while the Earl of Cromer, the Lord Chamberlain, worried that the character of ‘Signor Whale-Blubber’, a clear reference to Mussolini, might offend ‘sensitive foreigners’. Even as late as 1939, the theatre censors, anxious not to embarrass a government committed to détente with Germany, were deleting negative depictions of Hitler and Mussolini, and even words such as ‘Nordic’ and ‘Concentration Camp’.

The year after the London opening of Anything Goes in June 1936, Wodehouse received the Mark Twain Medal in recognition of his‘outstanding and lasting contribution to the business of the world’. In a letter to William Townend, he enclosed a list of former winners of the medal saying ‘[this] will give you a laugh’. The first on the list and first recipient of the medal was none other than Benito Mussolini. His medal bore the inscription ‘Mussolini, Great Educator’.

After infidelities on both sides, Mr and Mrs Sweeny divorced in 1947 on the grounds of ‘constructive desertion’, and two years later, on the luxurious Golden Arrow boat train returning from Paris, Margaret met Ian Douglas Campbell, the Duke of Argyll.

But that’s a whole other story…

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.