“I could tell him, too, that to know and love one other human being is the root of all wisdom.”

– Evelyn Waugh, Brideshead Revisited

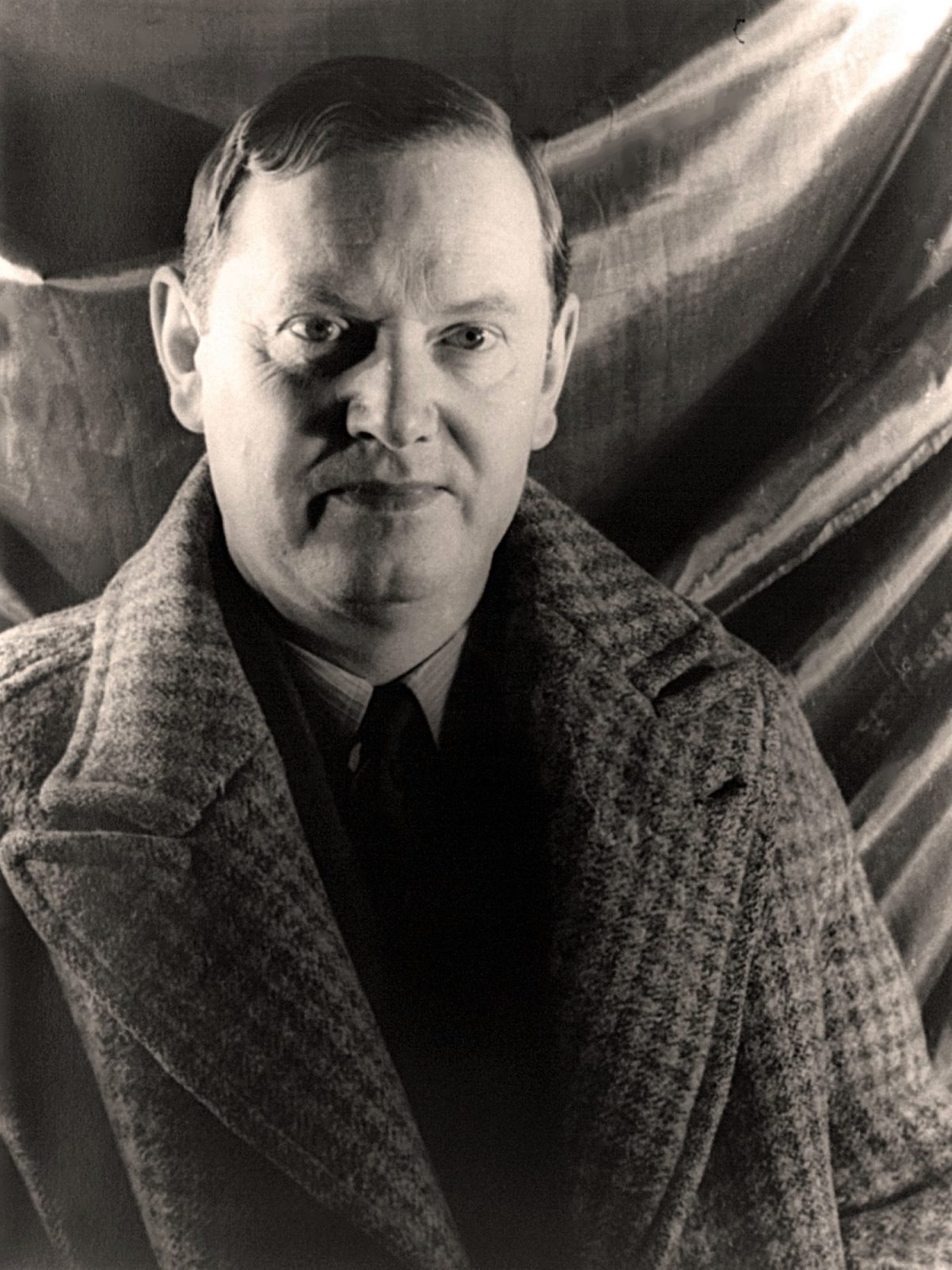

One of the best and greatest biographies ever produced about Evelyn Waugh is written by a man called Duncan McLaren. His biography Evelyn!: Rhapsody for an Obsessive Love was published to great acclaim in 2015.

Since then, McLaren has continued his biography online producing an all-consuming work of genius which now consists of around five or six books. I would suggest it’s time some large publishing house should sign-up Mr. McLaren and his epic biography and publish his superlative work as a multi-volume edition.

McLaren’s biography of Waugh is one of the most brilliant, original, funny and insightful ever produced. It draws the reader in with tales of Waugh’s influence on people like David Bowie, or his similarities to Picasso, and even has the courage to imagine conversations between Waugh and his friends which present a more human and fully realised character than most cut-and-paste biogs.

Having spent many enjoyable hours poring over this excellent biography, it was inevitable I was going to write to Mr. McLaren and find out all about him and his work.

Tell me about yourself?

Duncan McLaren: I was born in the traditional, country town of Blairgowrie in 1957, our family living in a house hard by one side of an enormous church, and I now live in a house, on my own, hard by the other side of that same church now derelict. That tells you exactly how far I’ve come in this transformed world. Luckily, I’ve got my writing to keep me anchored. And motivated. Or just busy.

What about your childhood?

DM: From the age of six to thirteen, I was living in Hamilton (as you’ll know, a large town near Glasgow with a huge council estate; back then it was what I might now describe as a deprived area), and that was an important time for my development, as it is for anyone. At six-years-old I would look for a quiet corner to hide away from the running, shouting, fighting kids. Just me? I think a few girls were pretty nonplussed by the situation as well. We were well dotted around the place, isolated and miserable.

What particular memories stick with you?

DM: There was a game called ‘kingsie’ (related to another game called ‘dodgy’) which started with someone having to throw a tennis ball against the fleeing body of another child in the herd, in order to get them to become part of the hunting team. The hunters would slowly increase in number, until there came a time when the hunting group got very efficient. The ball was thrown between hunters, and the hunted were picked off with ease. The hunted could protect themselves from the thrown ball by punching it away, but they were not allowed to catch it. I did join in this game (perhaps playing it was compulsory for boys) and I was pretty good at it, judging where there was space in the playground, which boys were likely to fumble the ball, who had a poor throw, and so on. So I tended to survive to the later part of the games, though the end was inevitable. There was one kid who was especially good at it. He was bold, blonde-haired, stocky and fast; he shouted a lot, and he was lucky. Seared in my memory is the ball flying fast and straight towards the back of his head when he happened to stumble. The ball missed him and he celebrated by spending the next few minutes avoiding the ball in various skilful and exciting ways. I never talked to him. But I guess he was the first person I wanted to know more about. In other words, the shyest, mildest, most self-conscious boy in the playground was fascinated by the pluckiest, cheekiest and brightest of boys.

Fast forward to the finish of my education, a state school kid shuffling around Cambridge feeling just as isolated as he had done at Udston Primary, partly because the majority of the undergraduates (all men, it was an all-male college in the late ’70s) were already securely networked with friends from their private schools. I was once called the most boring man in Cambridge. Not to my face, as I would have taken the opportunity of pointing out that this made perfect sense given that I had been the most boring boy in Hamilton. The gigantic quad at Downing College could have been the venue for the most amazing game of kingsie. It never happened. Or, if it did, I wasn’t invited.

When did you first discover Evelyn Waugh‘s work? What did you like about it?

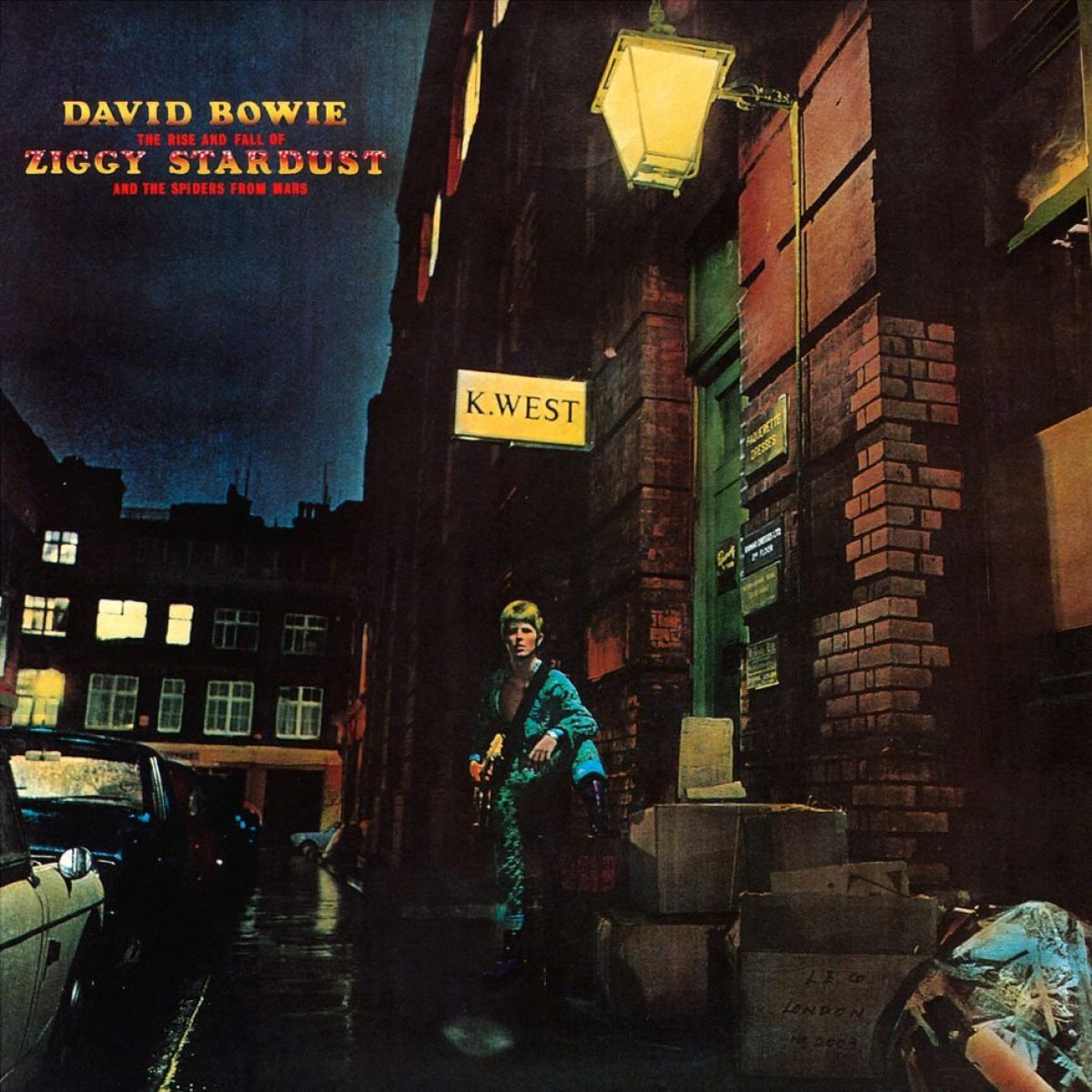

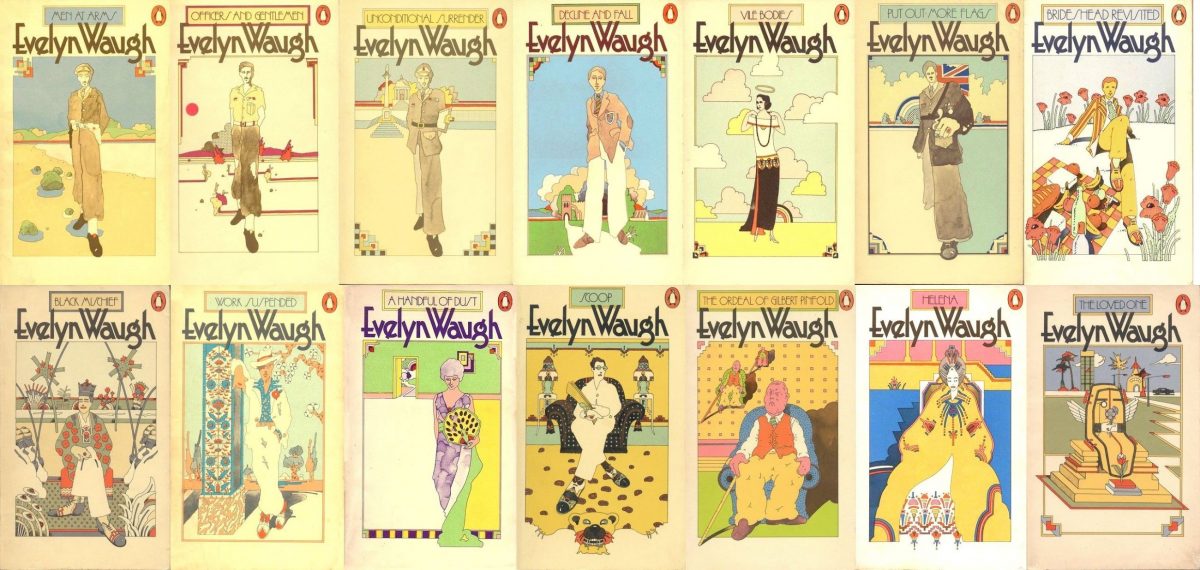

DM: I was seventeen. I’d been reading fairly widely, or at least as widely as the Penguins stocked in the local WH Smith (my family was living in Hemel Hempstead by this time) would let me. I was struck by the humour in Waugh, as I was later by the humour in Viz (equally male-centric). I realised that the author was using words in a very clever and subtle way to preserve his self esteem and his idea of himself. He seemed to be turning worldly failure into a personal success. Also, the covers of the paperbacks were fabulous. I think they were designed by someone of the glam rock generation. I would be lying on the brown beanbag in the lounge of my parents’ house, in that post-school-day slot, listening to David Bowie records while reading Evelyn Waugh novels. That remains a vision of teenage happiness for me. Living the dream before reality kicked in again, through work of one sort or another.

What happened next?

DM: I was reading Evelyn Waugh as well as Geography at Cambridge. It was the former that kept me sane. Why on earth was I reading Geography when my only interests had ever been books, paintings and records? We were given grants in these days to enable us to spend three years at university. There seemed to be no time pressure to sort ourselves out for jobs, which has its down side. But maybe an extended adolescence is a good thing if you are, very slowly, almost by chance, going to evolve into an artist.

What is special about Waugh to you and in comparison to other writers?

DM: It’s in adolescence that we are most open to new art. We then carry this with us through the years, and the constant engagement with it leaves its creators in an unassailable position among our preferences.

Decades after adolescence I read the books of, say, Julian Barnes, and enjoyed them. But I won’t ever be putting Barnes on a par with Waugh in my personal pantheon, because there has been insufficient time to grow with his books and his understanding of the world. Maybe a better example is Irvine Welsh. I was 36 when Trainspotting came out as a novel. I realised straight away it was brilliant, on a different level (of originality, of energy, of ambition) to anything else written in the 20th-Century by a Scot. And I could relate to it in some ways, but not in others. So I never quite committed to it, and though I’ve read other books of his, and been impressed by astonishing qualities, I’ve not read them all, and I’ve not even considered researching his life. It’s like appreciating what my brother got me to listen to of the Smiths. I loved Morrissey’s music, his vibe, but I was from Bowie’s generation, had all the albums and had listened to them hundreds of times. Bowie was embedded in my being. The first cut is the deepest.

When did you decide to write a biography on Waugh? Why did you decide to write it in such a brilliant and original way?

DM: I decided to write about Evelyn Waugh in the way I did because I’d just had great fun, and some success, taking a similar approach to the life of Enid Blyton.

DM: But you say ‘brilliant’, about my writing about Waugh, which is very nice of you, so I’ll address that. It starts with a rigorous chronology and geography (that again, so maybe I didn’t waste the government’s money). Things happen to Evelyn Waugh in a particular place at a particular time. So that has to be pieced together, and in so doing you realise who else was there. The picture builds up, and as you’re making it more three-dimensional, Evelyn and his mates start talking and doing stuff. You hold on for grim life to the authenticity of the scene, never forgetting your sense of humour and your moral compass. Then out pours the original insight. Sometimes I struggle to contain it all in suitable vessels.

What else have you written?

DM: My first published book was about the London art world of the 1990s. I visited galleries and avant garde events, looked at the work, and then trusted my instincts, not particularly caring what the artists (Tracey Emin, Douglas Gordon, Bob and Roberta Smith, Richard Long, etc.) wanted me to feel or think or write. The result, Personal Delivery, was published fifteen years into my writing ‘career’, after having got virtually nothing else in print before that, and it immediately got me a column with the Independent on Sunday and a letter and review and phone call from David Bowie. In other words, it was understood by taste-setters to be original. But I had to leave London to look after my elderly and increasingly frail parents (Time, he’s waiting in the wings./ He speaks of senseless things./ His script is you and me, boy.) I gladly did this as they’d provided a loving home (a refuge from the misery of school) when I was growing up.

In rural Perthshire, with far less art to look at, I decided to focus on individual artists/writers. And the first one was Enid Blyton who had dominated my reading from pre-school, when it was the Noddy books, to eleven, when I was captivated by the Famous Five as well as Fatty and the Find-Outers. I’d vaguely assumed the signature on book covers said ‘Gnid Blyton’, and I suspect I’d subconsciously translated this as ‘God Almighty’. The writer of all these fresh and vivid books was such an awesome force of nature, and it was a fascinating process to uncover how she operated.

What I found most interesting was mining the connections between what happened to her as a person and what she wrote in her books. Now, because Blyton had such easy access to her imagination, and because she wrote for children, this wasn’t always the most productive approach to writing about her creativity, though it did work with the Find-Outers books, set in Peterswood, which is effectively Bourne End in Buckinghamshire, where she raised her two daughters. It was far easier to investigate Evelyn Waugh in this way. I can trace just about everything that Waugh wrote to his direct experience. Which isn’t to say he’s not using his imagination to cut and paste, to layer and twist.

There is one other thing I’ve written that I’d like to mention, and that’s PEN PALS, which can be read online. This is a book that investigated the 32 writers who, like me, had a short story included in an anthology called PEN NEW FICTION 2, which came out in 1987, 30-years previous to my project. They included 16 women, who have had a tough time of it since; Ian Rankin, much the most successful of us; and a guy called Charles, who was in prison for a pretty serious crime when I was doing the research. PEN PALS sets out to find out what happens to writers: their careers, their youthful ambitions, their egos and their sense of self. It’s a part of my repertoire that I hope shows I’m not just a two-trick (Enid and Evelyn) pony. I hope to revisit the 1987 anthology on the 40th-anniversary of its appearance, in seven years time. Do I mean that? Because, by then, illness, terminal failure, and death are likely to have cast a deeper shadow over the individuals who comprise this non-existent group.

What can we learn from reading Evelyn Waugh? What life lessons?

DM: The qualities inherent in Waugh that I used to bolster myself with when young (irony, humour, the primacy of art), I’ve tried to distance myself from later in life. Sometimes the best way forward is to live a healthy, well-balanced, straightforward life amongst other people. Waugh was not good at this. He drank too much, always. He became inflexible in his opinions as he got older. His right-wing views, largely ironic when he was younger, solidified and became horribly serious. He professed to believe in God in a way that seems un-nourishing. He began to lose the few friends he had, he was so rude to everyone. He died at the age of 62, having become bored with life and longing for death.

At 63-year-old, I’m having to tend poor Evelyn’s grave, diverting readers’ attention to his earlier years and books, when he was funny, sweet and full of joie de vivre. Like the boy who was best at kingsie.

What are the best Waugh books? Can you offer up your top ten?

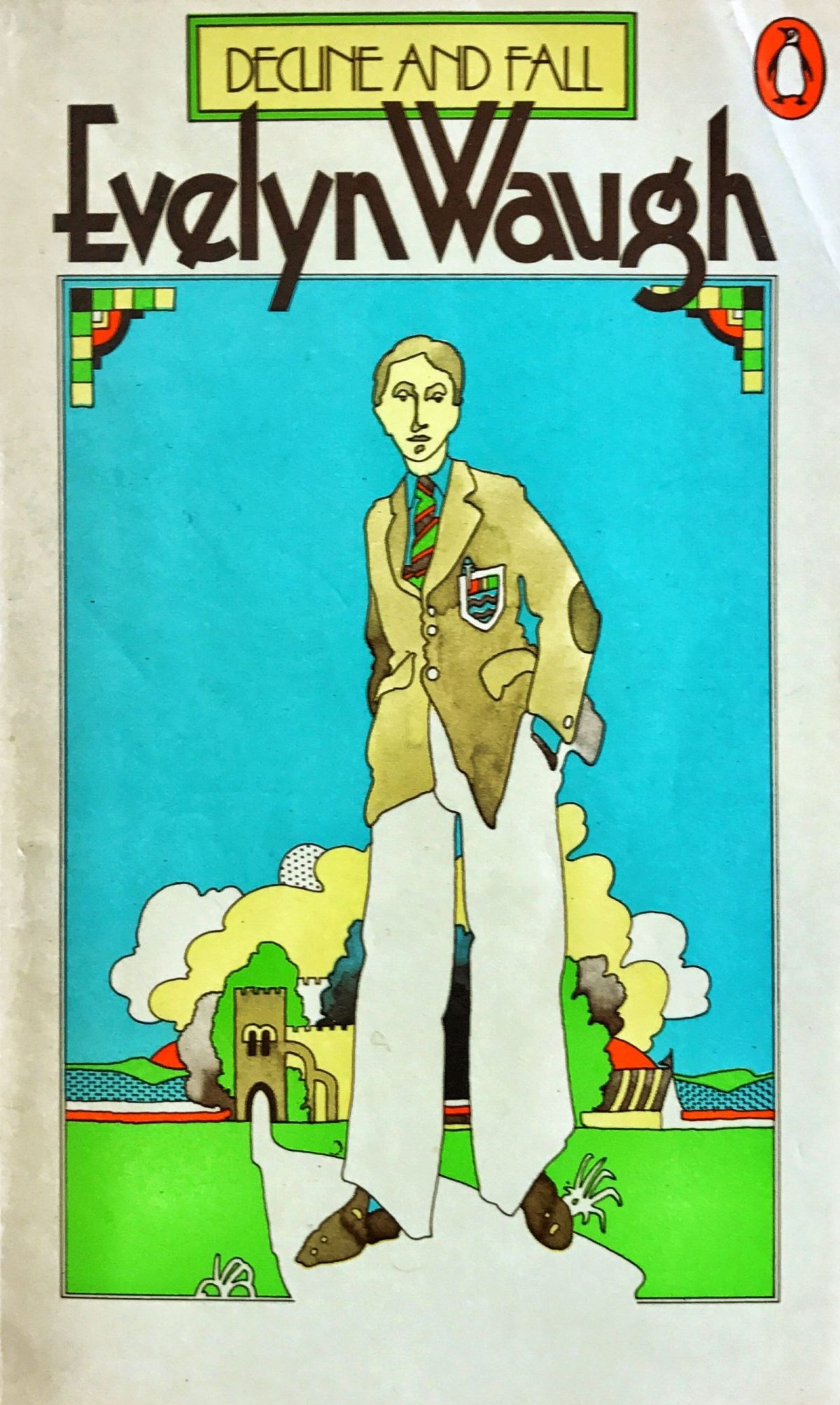

DM: Decline and Fall. You struggle at university, you struggle at your first job. You struggle to impress the people you’re sexually attracted to. Put that through the Evelyn Waugh mincer and you get the funniest story ever, from which Paul Pennyfeather emerges unscathed.

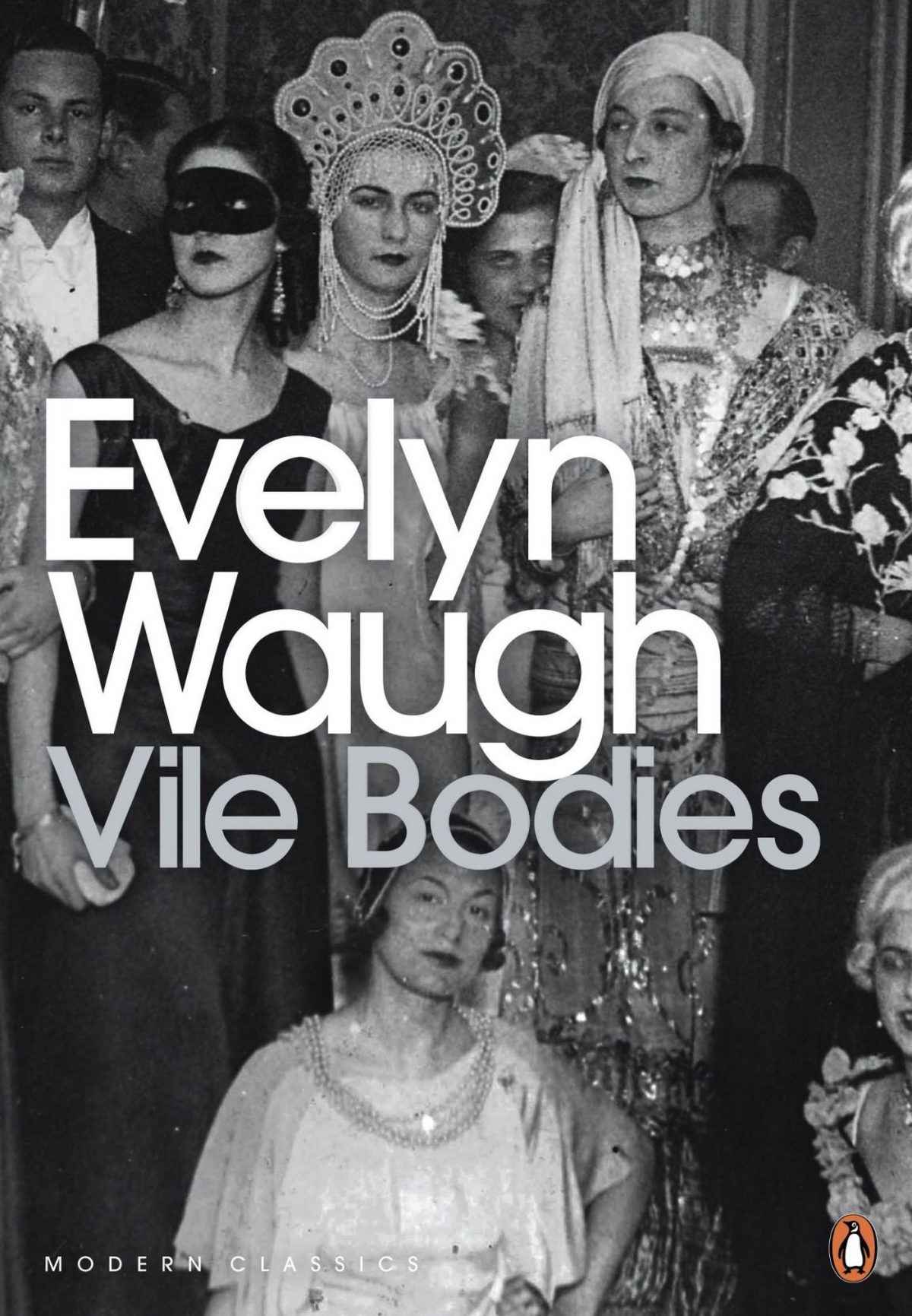

DM: Vile Bodies. Waugh’s wife left him for another man during the middle of the writing of this novel. So he went from being the happiest of men to the most upset. Can you tell that by what happens in the story? Well, yes: Ginger Littlejohn takes Nina from Adam, but Waugh has his emotions under tight control. The narrative continues in its poised and brilliant, rollercoaster-way. Red-hot experience transformed into cool art.

DM: Ninety-Two Days. A travel book. Waugh travels up the Amazon in an effort to distract himself from a broken heart. A totally mad and pointless journey, boring and painful to endure. But the reader – whenever he/she puts the book down – is aware that something heroic is going on.

DM: A Handful of Dust. The travel book re-written as a novel. Its themes of adultery, loss and despair, beautifully and enduringly captured. Waugh’s finest novel. His funniest too, though never was comic more tragi-.

DM: Scoop. A naive, nature writer is sent to Africa as a war correspondent. The opening and closing sections, set in Britain, are hilarious juxtapositions of innocence and experience, rural and city life. The section set in Africa I found thin and boring until I properly researched it. But a reader shouldn’t have to repeat an author’s research.

DM: Put Out More Flags. Waugh wrote this in 1942, on a troop ship coming back round the horn of Africa after fighting in the Middle East. This book is about the phoney war of 1939 when all his chums were positioning for having a ‘good war’. Funny, sharp and with a devastating character assasination of Ambrose Spruce (Brian Howard in real life).

DM: Brideshead Revisited. One layer is strange stuff about religious belief in a stately home setting. Another is the most warm and nostalgic look back at a university friendship.

DM: Men at Arms. The opening book in Waugh’s War Trilogy, in which he ransacked the diaries he kept (illegally) during the war. Training to be an officer alongside a group of dubious characters. None more so than Apthorpe, who has his own Thunderbox (toilet). Fascinating to see where Waugh departed from his actual experience.

DM: The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold. Poor Evelyn went crazy on a ship bound for Ceylon due to excessive drinking mixed with taking laudanum to help him sleep. He lightly fictionalises his problems in this self-lampooning, hilarious- yet-touching portrait.

DM: Unconditional Surrender, The third book in the WW2 trilogy. Again, heavily based on his diaries. Waugh wasn’t sure he’d hang on to his talent long enough to write this, but he did. The imaginative twists, the characterisation and the layering are as effective as anything in his ouevre. Take a bow, Evelyn. Aged 56, by the time he wrote this, and visibly failing.

All these books are best read in the Penguin edition featuring covers by Bentley/Farrel that were in currency from the early 70s to the early 80s.

Where does Waugh stand in terms of literature?

DM: Well, I don’t know. I deliberately don’t think that way, as there are so many academics who go on from their English degrees thinking along these lines. But if you push me… Joyce and Woolf are two of the most fashionable figures now, it seems to me. Waugh gained some familiarity with modernism then rejected it. But he didn’t revert to nineteenth century realism, rather jumped to his own version of post-modernism. In other words, I think he was ahead of his time. I have a feeling his reputation will go from strength to strength. Certainly, it will if I have anything to do wiith it. But that would mean that certain of his views (his Toryism, racism and misogyny) would have to be seen in perspective, and possibly forgiven. No sign of that in the present climate, which is perhaps as it should be as we continue to work on the moral framework of society. In other words, equality of opportunity and outcome is more important than the freedom to think and do what you like, which is what Waugh champions.

What will happen with your biography?

DM: My book (Evelyn! Rhapsody for an Obsessive Love) was published by a tiny firm in 2015. But it was very positively reviewed in the national press so it did sell 500 copies. It would have sold a lot more if the book had been physically in existence by the time that those reviews came out. But you simply can’t expect everything to go smoothly when the team behind a book is so small. And because I’ve set up a website where I carry on with the Waugh research, a trickle of sales continues. (At least I think they do, Jeremy, my publisher, is loathe to say.)

I’m now more interested in the website than the book, as it has a more flexible format. I’m pouring content in there at a rate of knots. Each essay is full of scrupulous research, piss-taking humour, images, insight and enthusiasm (if I say so myself).

The site now contains five or six book-length sections that I am constantly adding to. For instance, a project begun earlier this year is called ‘The Brideshead Festival’. The idea is that all Waugh’s contemporaries from Oxford gather at Castle Howard in 2020 to commemorate his most famous novel. It’s prompted me to research the interlocking lives of this generation of writers almost all of whom had a private school then Oxford background. Indeed, Oxford 1923-1926 is a World Heritage Site in terms of writing. Graham Greene, Evelyn Waugh, Anthony Powell, Henry Yorke (Green), Robert Byron, Cyril Connolly, John Betjeman, and more, all knew each other there and subsequently. They all published novels, diaries, letters, and I have a decent library of their stuff. Nancy Mitford, who corresponded with Waugh for decades, with wit and charm on both sides, is my narrator for many chapters, before she leaves the scene to Waugh, Greene and Powell for the last few. Meanwhile, my investigation of Waugh’s Piers Court years – two decades when Evelyn and his family lived in a Georgian mansion in Gloucestershire – looks like it could go on forever, there are so many topics to explore, so many angles into the material. So you see my biography of Evelyn Waugh is by no means finished yet. I wonder if Boswell ever stopped thinking and writing about Samuel Johnson.

What have you learned from writing it?

DM: There is a sweet passage in Brideshead which begins like this: ‘I could tell him, too, that to know and love one other human being is the root of all wisdom.’ Even when that one other loved human being died when the person doing the loving was only eight years old? Yes. Even when the loved one was never a particularly selfless, or socially aware, or empathetic individual, except when in his early twenties? Yes. Even when the loved one was a cranky old absurdity in his mature years, who came to see himself as boring, irrelevant and irretrievably fucked? Ah, those would be the Combe Florey years. I have avoided investigating them in depth so far. I feel they should wait until I am a lot older. Say, about 90.

You can Read Duncan McLaren’s biography of Evelyn Waugh here.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.