The writer Terry Southern would joke about big Stan Kubrick being on the line from Old Smoke. He liked Kubrick–though he had never met him–and liked the sound of “Big Stan” and the image of him calling from his London office–though “Big Smoke” may have been better known soubriquet for the English capitol–but let’s not quibble over the fancies of such a brilliant man as Southern.

One day, of course, Big Stan did call from his office seeking Southern’s help with a new project about nuclear war, or more precisely “our failures to recognise the dangers of nuclear war.” Kubrick had originally toyed with a melodrama on the subject, but then he “woke up and realised that nuclear war was too outrageous, too fantastic to be treated in some conventional manner” other than “some kind of hideous joke.” It was suggested to Kubrick that the man to help him create such a hideous joke was novelist and screenwriter Terry Southern.

As he later described it in his essay “Strangelove Outtake: Notes from the War Room” for Grand Street magazine in 1994, Southern had become friends with the actor, satirist (of Beyond the Fringe fame), writer and handy doctor Jonathan Miller–a man allegedly able to write Southern prescriptions for Seconal–to whom he had given a copy of his novel The Magic Christian. This book was then passed onto Peter Sellers, who was so impressed by it that he bought one hundred copies of the novel to give to friends. One such friend was Stanley Kubrick.

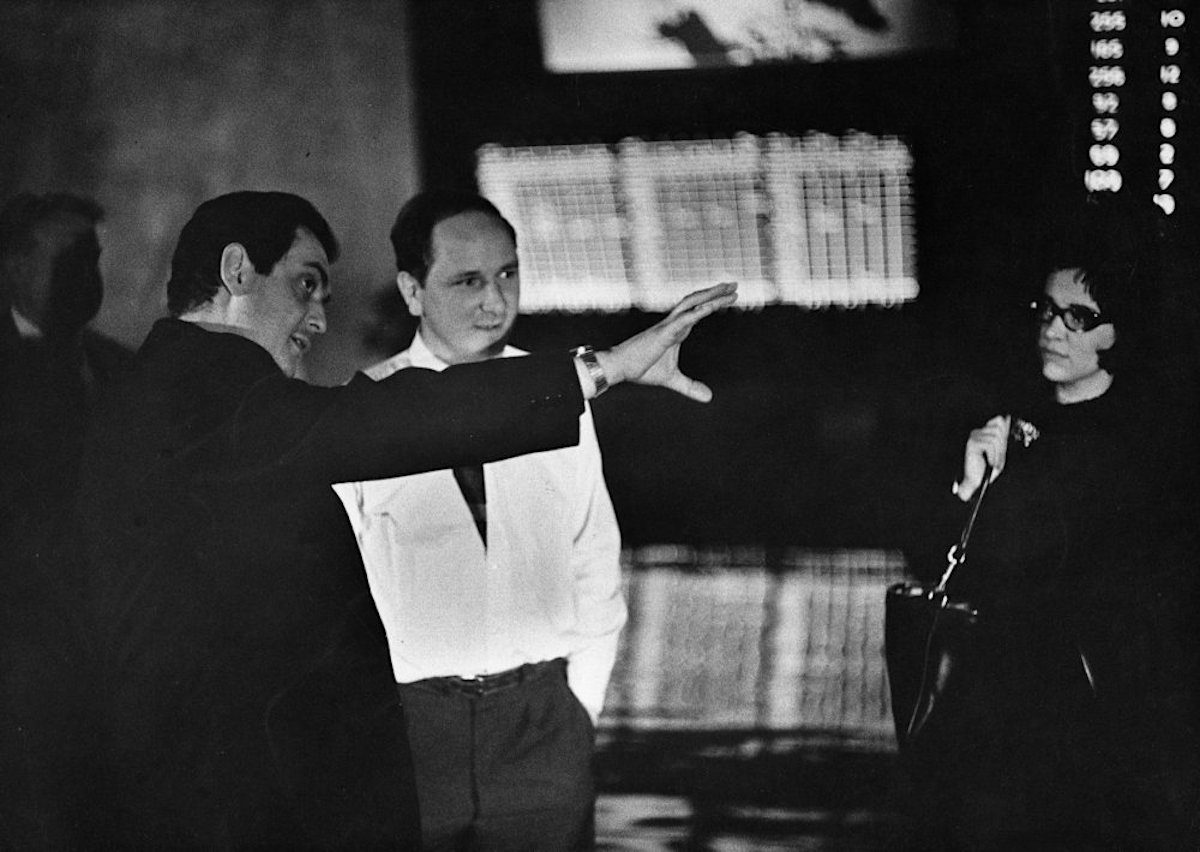

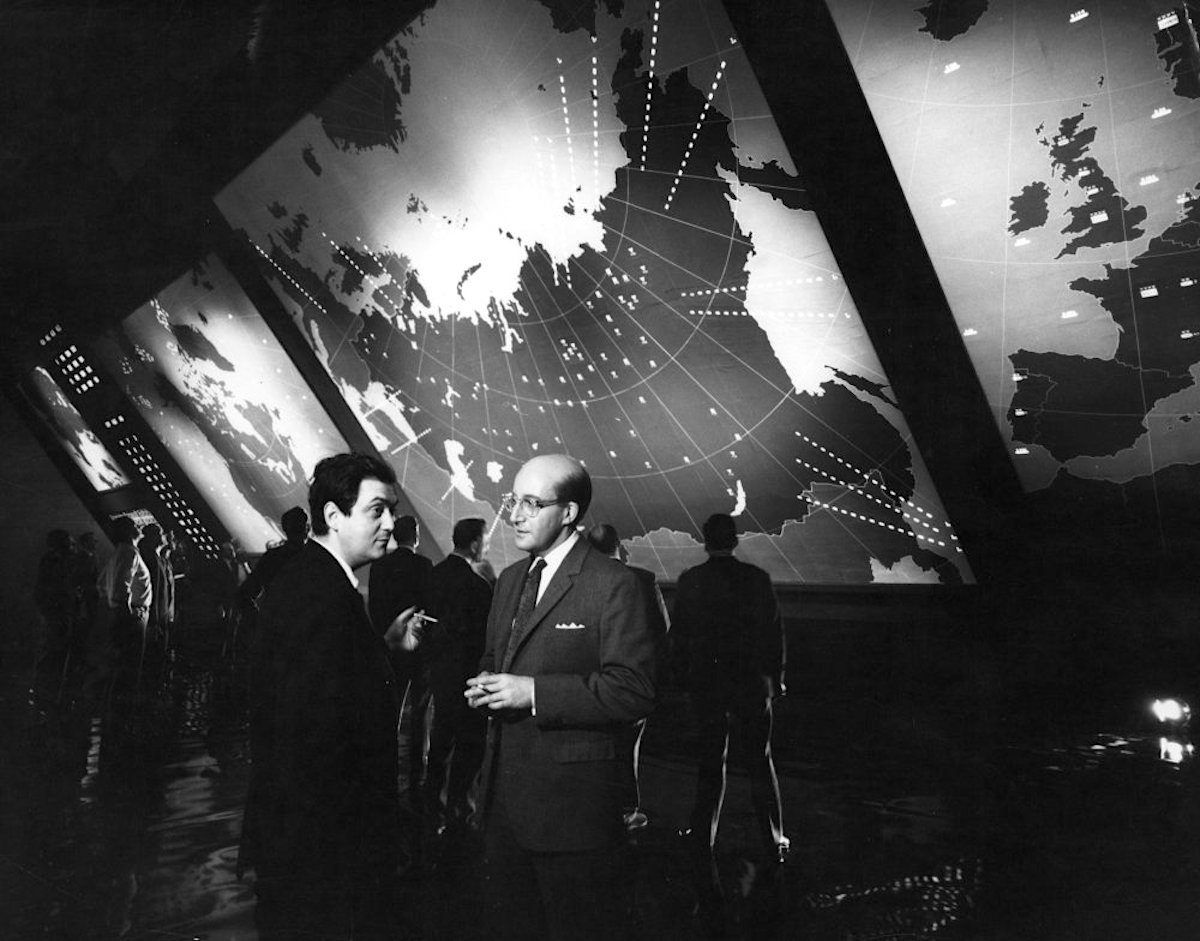

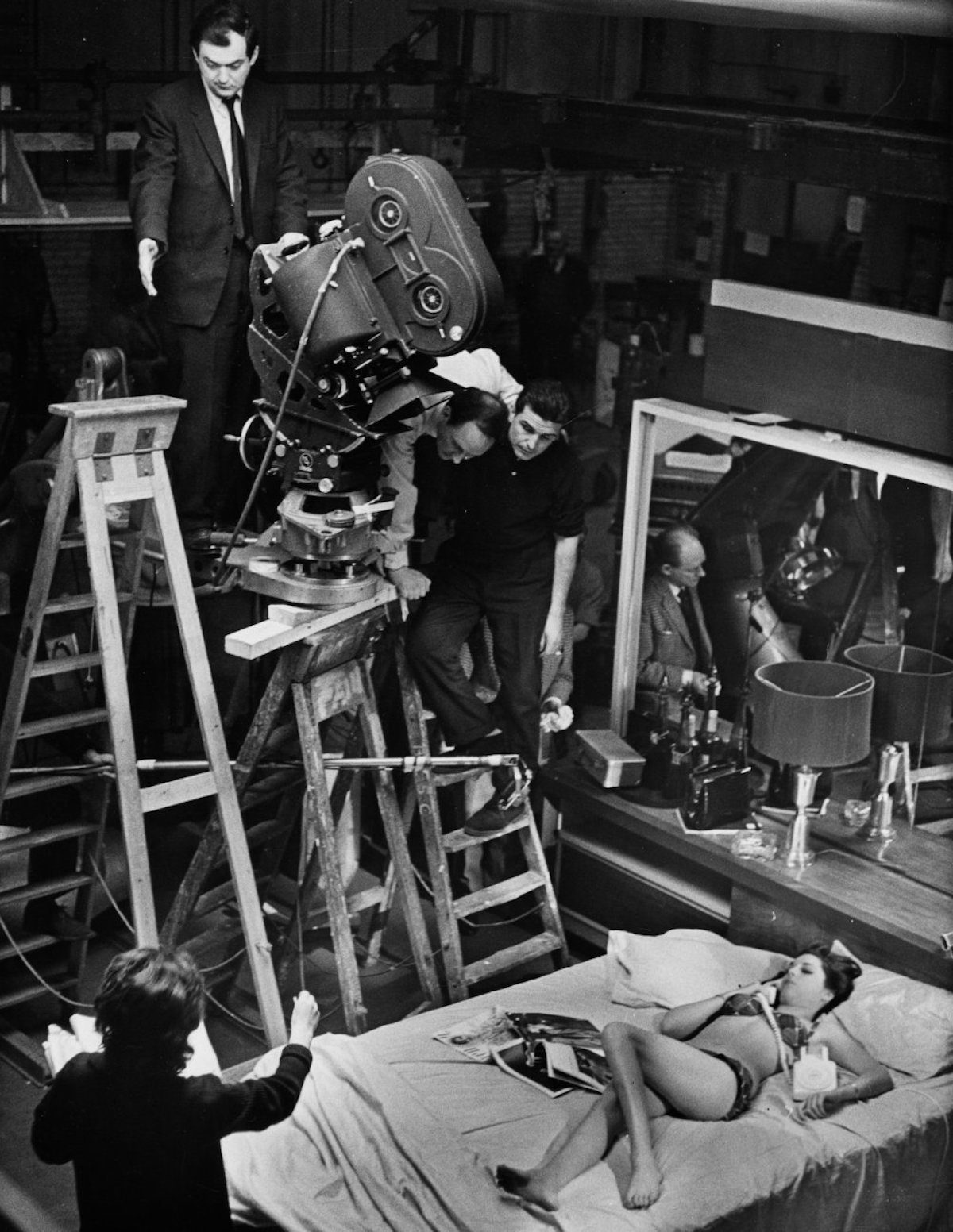

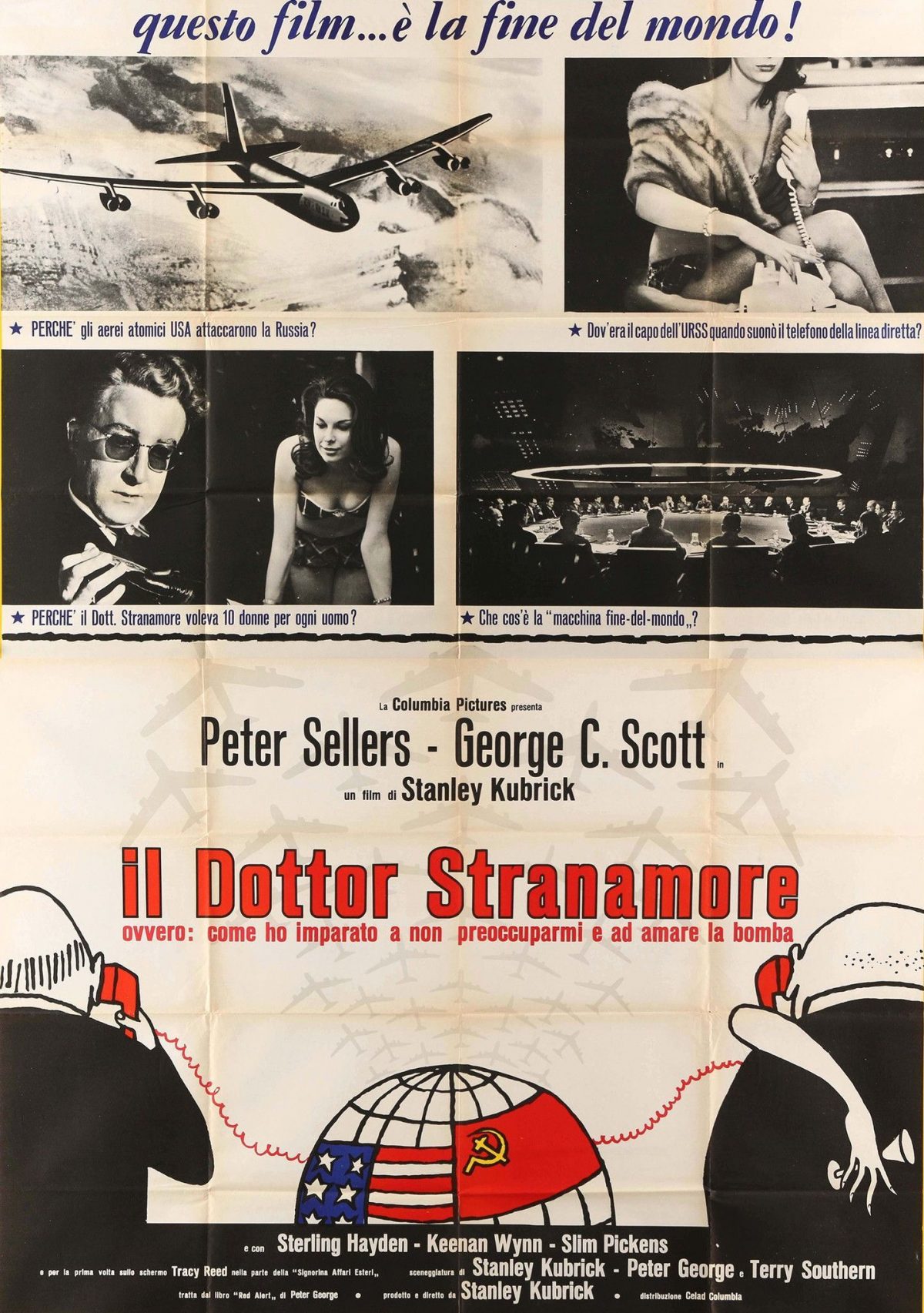

Kubrick had optioned Peter George’s book Red Alert (aka Two Hours to Doom) and was set to make a literal adaption of its disturbing tale of near nuclear armageddon. He had set up his “Command Post” at Shepperton Studios, and was working on a screenplay with George when he realised the impossibility of making a melodrama out such an horrific subject and thought the only rational response was to make “a nightmare comedy.”

Let’s spool back for a second and edit in some background scenes. 1962: It wasn’t just the possibility of nuclear fallout in the milk that concerned most people during the late 1950s and early 1960s, there was a genuine, palpable, wet palm fear that the world was on the verge of an all-out nuclear war. America’s new President John F. Kennedy had started things rolling by deploying nuclear warheads across Turkey and Italy that had the capability of firing on Russia. Then there was the Bay of Pigs disaster of 1961, when the CIA sponsored a counter revolutionary force to invade Cuba in a misguided and ill-conceived attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro. In response, the Cubans asked Russian President Nikita Khrushchev to deploy nuclear warheads on their soil. Khrushchev was only too happy to oblige, as it upped the ante and put the Soviets on a par with America, giving them the same capability of wiping most of the USA off the map. Kennedy gave a televised address to the nation explaining the grim reality of what was at stake:

It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.

Not to be outdone, Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara called his hand:

Direct aggression against Cuba would mean nuclear war. The Americans speak about such aggression as if they did not know or did not want to accept this fact. I have no doubt they would lose such a war.

For the first and only time in American history, twenty-three nuclear-armed B-52s were on continuous airborne alert, sent to orbit points within striking distance of the Soviet Union. China said, “650,000,000 Chinese men and women were standing by the Cuban people.” While Pope John XXIII begged “all rulers not to be deaf to the cry of humanity.” As the world was being pulled to the brink of imminent annihilation, a series of secret negotiations took place between agencies for Khrushchev and Kennedy. The Soviet president wrote to the young American leader:

Mr. President, we and you ought not now to pull on the ends of the rope in which you have tied the knot of war, because the more the two of us pull, the tighter that knot will be tied. And a moment may come when that knot will be tied so tight that even he who tied it will not have the strength to untie it, and then it will be necessary to cut that knot, and what that would mean is not for me to explain to you, because you yourself understand perfectly of what terrible forces our countries dispose.

Consequently, if there is no intention to tighten that knot and thereby to doom the world to the catastrophe of thermonuclear war, then let us not only relax the forces pulling on the ends of the rope, let us take measures to untie that knot. We are ready for this.

Khrushchev was playing a game–he wanted the American nuclear missiles removed from Turkey and Italy, and made it clear if these weapons were removed, the Russians would keep their nuclear armaments out of Cuba.

As footnote to the kind of figures we’re talking about here’s what the UK government’s “Operation Square Leg” claimed after a secret mock nuclear attack organised to estimate the actual number of dead and injured in the event of a nuclear attack on Britain. The exercise assumed that “131 nuclear weapons would fall on Britain with a total yield of 205 megatons: 69 ground burst; 62 air burst.” It was estimated this would kill 29 million or 53% of the population; with 7 million or 12% seriously injured; and 19 million or 35% of the plucky Brits remaining as “short-term survivors.”

The fear of humanity’s seemingly inevitable nuclear annihilation at the push of a red plastic button was soon reflected in a range of novels, films, and TV dramas.

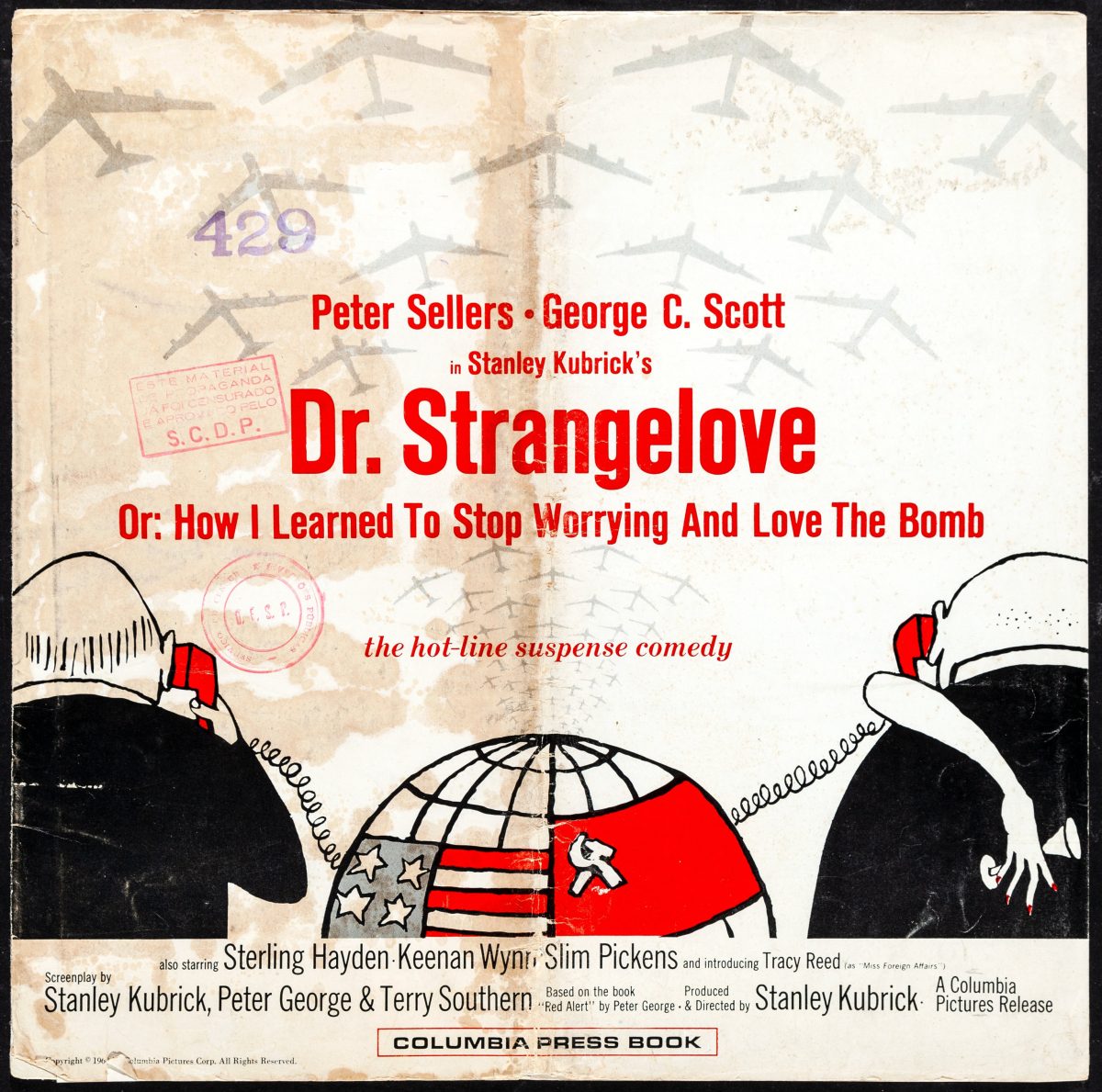

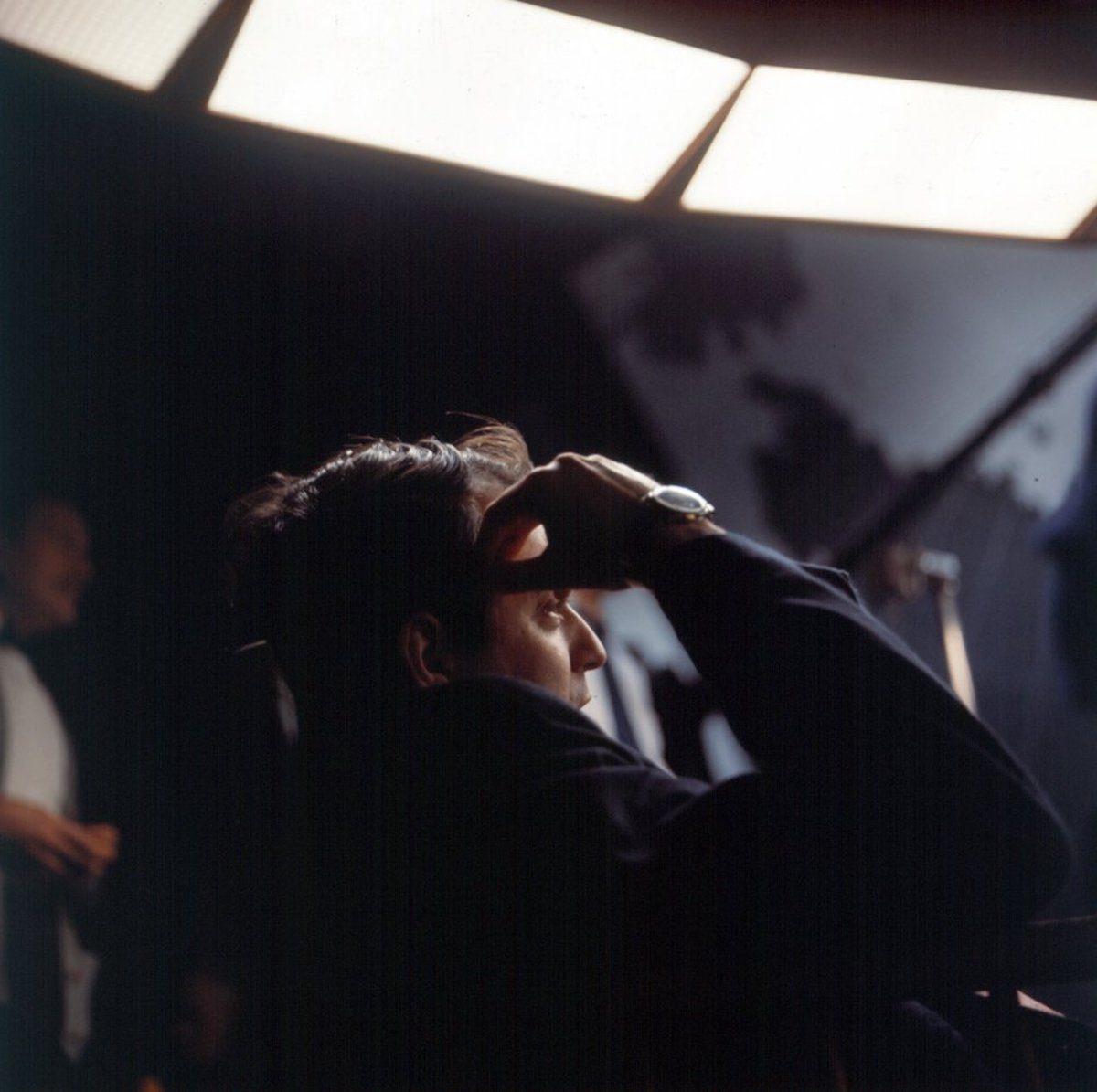

This was the background against which Kubrick developed his movie. At first he considered telling the story of Earth’s nuclear annihilation from the point of view of two visiting extraterrestrials, but he didn’t think this approach had the right amount of “inspired lunacy.” It was then “Big Stan” called Terry Southern to write a story using George’s novel as a loose framework. He wanted Southern to play up the absurdity of all-out nuclear war rather than a page-turning thriller. The result was Doctor Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb—“the most perfectly written comedic screenplay of post-war cinema,” as it was later described by film critic Alexander Walker.

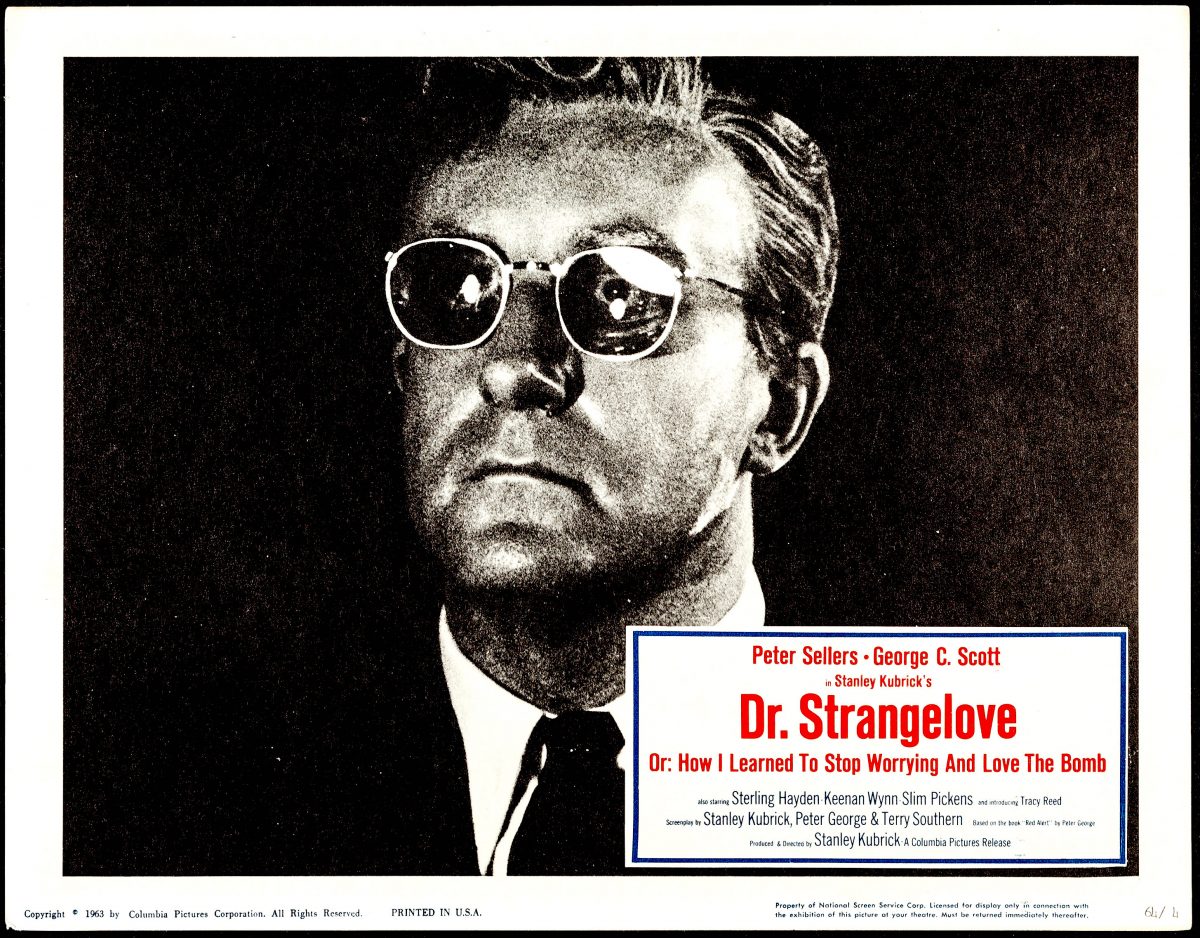

Kubrick had sold the idea for the project on the casting of Peter Sellers in four different roles: the President of the United States Merkin Muffley; Group Captain Lionel Mandrake, a British RAF exchange officer; Dr. Strangelove, the wheelchair-bound nuclear war expert and former Nazi; and Major T. J. “King” Kong, commander and pilot of a B-52 Stratofortress.

Sellers was delighted to be working again with Kubrick after their success together on Lolita, but he was daunted by the thought of playing four roles and quickly made his excuses:

Dear Stanley,

I am so very sorry to tell you that I am having serious difficulty with the various roles. Now hear this: there is no way, repeat, no way, I can play the Texas pilot, ‘Major King Kong.’ I have a complete block against that accent. Letter from Okin [his agent] follows. Please forgive.

Peter S.

Kubrick had given up smoking, had even banned it on set, but when he received this letter, he immediately sent out for a pack of smokes. Kubrick turned on the charm and started to coax Sellers into acquiescence. Knowing Southern was from Texas, he asked the writer to record Kong’s dialogue on to a tape so Sellers could finesse the accent. Sellers eventually and reluctantly agreed to play Kong, and collected Southern’s tapes and wandered around Shepperton sporting a pair of out-sized headphones trying to learn a Texan accent.

Filming of Major “King” Kong’s scenes was scheduled, but on the first day, Sellers arrived limping from a fall he had suffered the night before at an Indian restaurant. A run-through was reorganised for a less strenuous scene “which required Major Kong to move from the cockpit to the bomb-bay area [of the B-52] via two eight-foot ladders.”

Sellers negotiated the first, but coming down the second, at about the fourth rung from the bottom, one of his legs abruptly buckled, and he tumbled and sprawled, in obvious pain, on the unforgiving bomb-bay floor.

The following day, after a medical examination by a Harley Street doctor, it was announced that Sellers could not play the part of Kong. As Southern later wrote:

Once the grim reality had sunk in, Kubrick’s response was an extraordinary tribute to Sellers as an actor: “We can’t replace him with another actor, we’ve got to get an authentic character from life, someone whose acting career is secondary–a real-life cowboy.”

However, Kubrick had not set foot in America for about fifteen years and had little knowledge of possible “secondary actors of the day.” Southern suggested the actor Dan Blocker, who looked like an over-grown cherub and was best known for starring as “Hoss” in the cowboy TV series Bonanza.

“How big a man is he?” Stanley asked.

“Bigger than John Wayne,” I said.

We looked up his picture in a copy of The Players’ Guide and Stanley decided to go with him without further query. He made arrangements for a script to be delivered to Blocker that afternoon, but a cabled response from Blocker’s agent arrived in quick order:“Thanks a lot, but the material is too pinko for Dan. Or anyone else we know for that matter. Regards, Leibman CMA.”

As I recall, this was the first hint that this sort of political interpretation of our work-in-progress might exist.

Unwilling to delay filming, Kubrick recalled an actor he had met when he was set to direct Marlon Brando in the western One-Eyed Jacks:

[Kubrick] had noticed the authentic qualities of the most natural thesp to come out of the west, an actor with the homey sobriquet of Slim Pickens.

Born Louis Bert Lindley in 1919, “Slim” Pickens was a cowhand who worked the rodeo circuit from El Paso to Montana, sometimes competing, sometimes carrying out the deadly work of rodeo clown–that’s the guy who distracts the bull long enough to get any injured rodeo riders out of the arena.

Except for the occasional stunt work on location, Slim had never been anywhere off the small-town western rodeo circuit, much less outside the U.S. When his agent told him about this remarkable job in England, he asked what he should wear on his trip there. His agent told him to wear whatever he would if he were “going into town to buy a sack of feed”–which meant his Justin boots and wide-brimmed Stetson.

When Pickens arrived at Shepperton, Kubrick sent Southern over to see he was all right. The writer cheerfully cracked open a bottle of Wild Turkey to set the mood, and asked Pickens if he had settled into his hotel okay, and if everything was fine and dandy. Slim took a big slurp of his drink, wiped the back of his hand against and mouth and replied:

“Wal, it’s like this ole friend of mine from Oklahoma says: Jest gimme a pair of loose-fittin’ shoes, some tight pussy, and a warm place to shit, an’ ah’ll be all right.”

Spotter BFI

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.