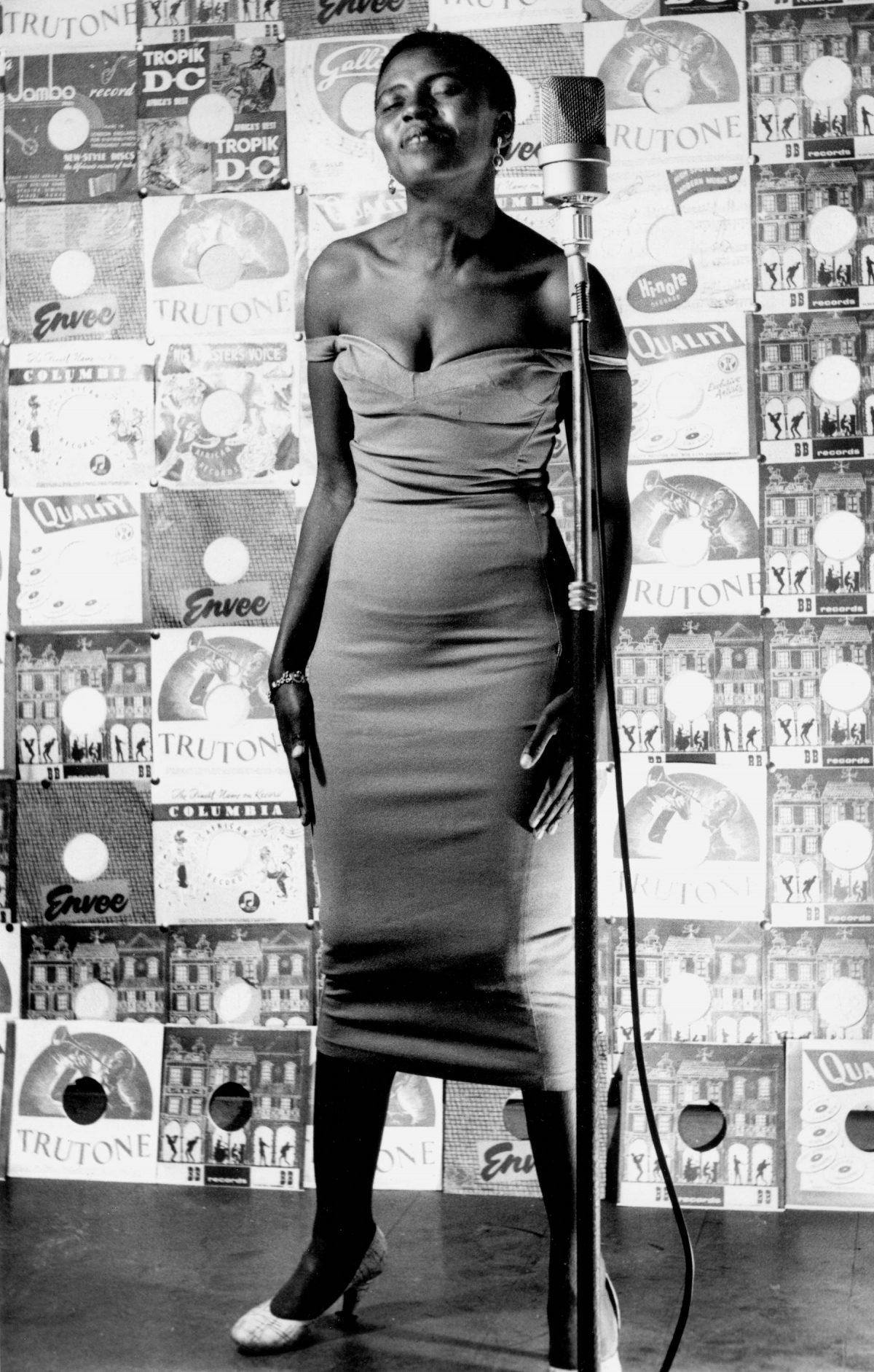

Priscilla Mtimkulu, described by Can Themba as ‘sweet and twenty….this lovely has fluttered in from Orlando East like a butterfly…you should see her eyes, soft, dreamy, sadly sweet…and her hair, wavey, wisps of black silkiness.’

1955

Our first adventure is birth. It’s the one we have no control over when it comes to the when, the where, or the family we are born into.

Jürgen Schadeberg was born in Berlin, 1931, just as the National Socialists were goose-stepping out of the bier keller and on to the streets to destroy the country. When he was a child Schadeberg asked his Mother who was the angry man shouting on the radio? He knew instinctively this man was bad. The angry man was Adolf Hitler.

At the start of his teens, Schadeberg was forced into the Hitler Youth. He hated it and everything it represented. Sometimes he marched backwards, or wore bright colours instead of the standard issue brown shirt. On other occasions he mimicked Charlie Chaplin as der Führer. One day, the police knocked on his Mother’s door and suggested she get her son under control. The threat was real. Jewish neighbours disappeared everyday.

After the war, Schadeberg worked as a trainee photographer. He was poor and hungry. He lived off bread and water. One day an editor noted how thin and hungry Schadeberg looked. He suggested he covered football matches and get paid for every goal he photographed. He earned money for food but learned to loathe football.

In 1950, Schadeberg moved with his family to South Africa. They thought it would be a better world away from racism and Nazis. The family arrived just at the moment Apartheid was inflicted on the country. Schadeberg began photographing the people and political movements. He became Chief Photographer, Picture Editor, and Art Director at Drum Magazine. Over the following decade, Schadeberg documented some of the most important figures and key moments in South African history–from Nelson Mandela, Moroka, Walter Sisulu, and Yusuf Dadoo, to the Defiance Campaign of 1952, the Treason Trial of 1958, the Sophiatown Removals, and the Sharpeville Funeral in 1960.

In the sixties, Schadeberg travelled across Europe photographing life in England, Scotland, Spain, and France. In the seventies, he travelled to America. He diversified into filmmaking but continued to document the world as he saw it. With a portfolio of work covering over seventy years, Schadeberg is now arguably our greatest living photographer.

Spanish men in a bar, Mijas, 1971.

When did you decide to become a photographer?

Jürgen Schadeberg: After the war in Berlin I was a trainee for a professional documentary photographer and then I was a volunteer trainee in Hamburg at the German Press Agency in the photographic department for three years. In 1950, aged nineteen, I went to South Africa and started my professional photography as a freelance photojournalist. For me photography was a way to communicate social issues and highlight human rights and social justice.

What were your first photographs and who were your influences?

JS: My first real photo was taken in an air raid shelter in Berlin in 1941.

In my early photographic days I had no influences and just went by instinct–in later life I admired such photographers as Cartier Bresson, Eugene Smith and Salgado.

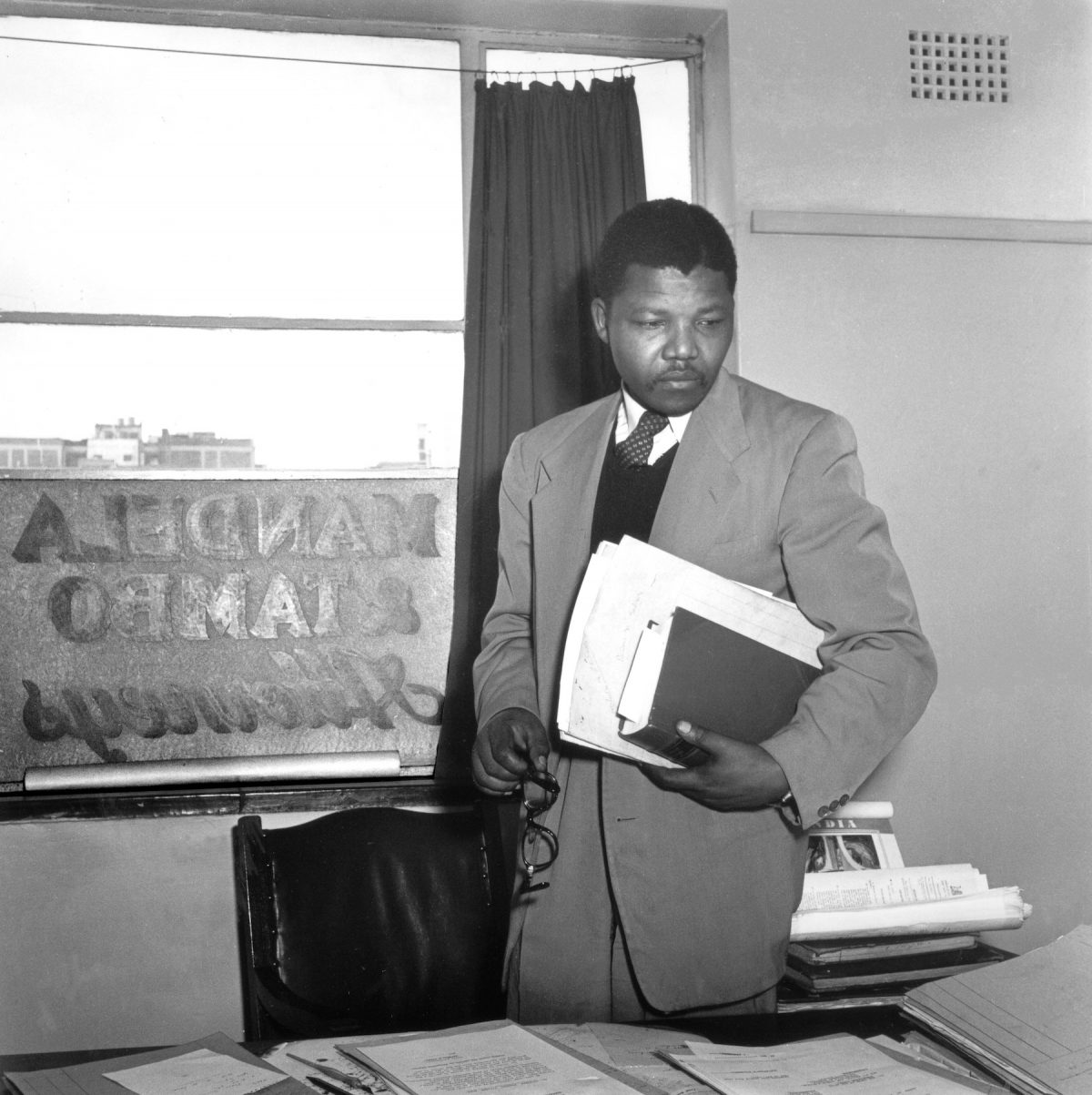

Nelson Mandela in the law office he shared with Oliver Tambo opposite the Johannesburg Law Court, 1952

Can you tell about the photographs from the Defence Campaign? What was it like living in South Africa then?

SG: I lived in South Africa from 1950-1964 when I recorded black social, cultural and political life during Apartheid including the 1952 Defiance Campaign, the rise and fall of the black township of Sophiatown, the Treason Treason Trial 1958 and Mandela from 1951. I returned to South Africa in 1985 – 2007 when I recorded post Apartheid life and social and human rights issues. I also made films together with my wife and partner Claudia which focussed on black history including jazz, the fifties and the history of the island prison of Robben Island. Life in SA is never dull and has its daily highs and lows.

Outside the Johannesburg S. Court. crowd protesting against the arrest of their leaders, 1952.

What was it like travelling through the UK in the 1960s? What did you think of Glasgow?

JS: The Gorbals in Glasgow in the sixties suffered from deep poverty which negatively affected families and children but there still existed a spirit of hope. The UK in the sixties was a grey place for me with a large poverty gap. My photo projects highlighted this divide including the homeless in London, life in Hackney and the non swinging side of Soho and in contrast the Cambridge May Ball and open day at Eton School.

What makes good photograph?

JS: Content, composition and training.

Waitress Break, London City Hall, 1979

Can you tell me about Six Decades of Jazz?

JS: I made a photo project, book and exhibition on the top 20th century South African jazz musicians, singers and performers. During the Apartheid period jazz was a form of defiance and protest which eased the burden of Apartheid. Jazz is one of my favourite music forms and I enjoy such musicians as the close harmony group The African Inkspots (whom we filmed many times) , blue queen Dolly Rathebe (whom we also filmed) and jazz diva Thandi Klaasen.

The Jazzomolos, Jacob “Mzala” Lepers (Bass), Ben “Gwigwi” Mrwebi (Alto Sax), Sol “Beeqeepee” Klaaste (Piano), Johannesburg 1953.

What was it like working in Germany?

JS: I did photo essays in Germany in the sixties and seventies for Die Zeit in Germany and the Sunday Times, Observer and Weekend Telegraph magazines which focussed on German Jews returning to live in Germany, the Neo Nazis movement – together with writer James Cameron–the building of the Berlin Wall and the assimilation programme for asylum seekers.

Hans Prignitz’s handstand on the St. Michaelis Church, Hamburg, 1948.

How important is photography for helping to change the world?

JS: An image is a thousand words and can be a positive force for positive change.

What is your personal favourite photograph that you have taken?

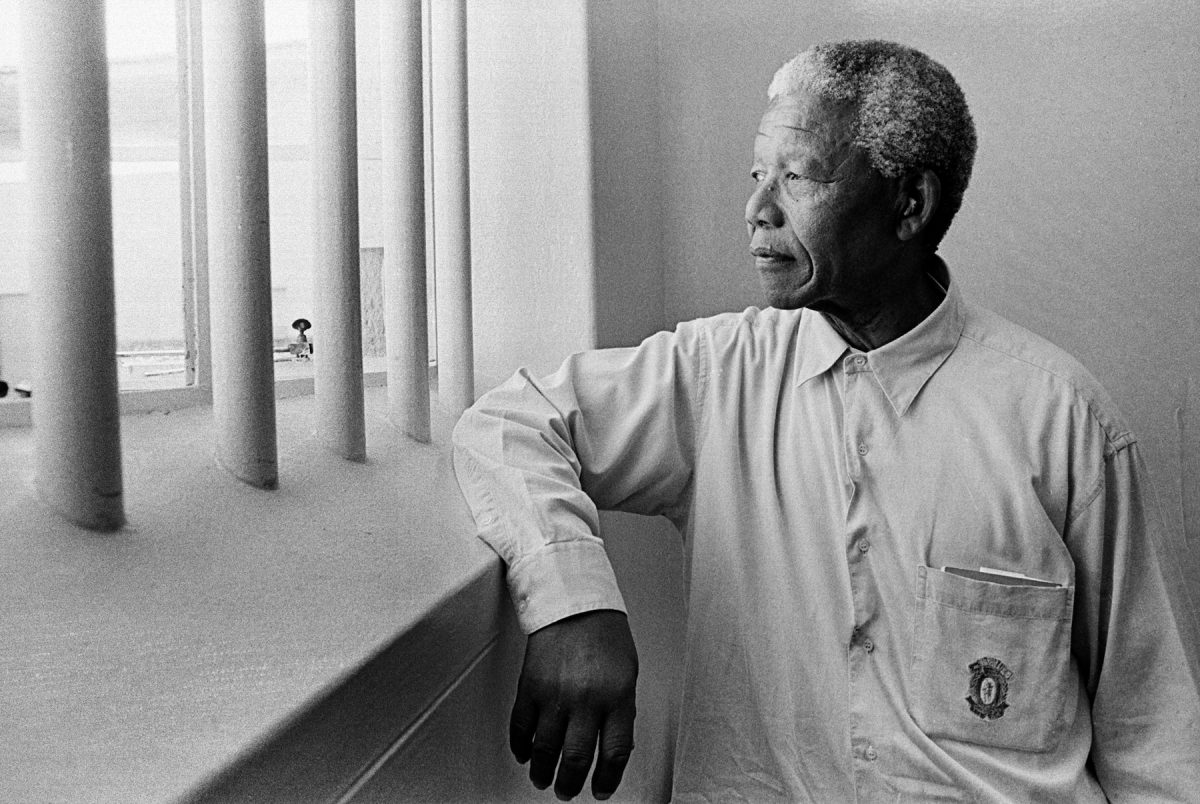

JS: The Hamburg Handstand 1949 is one of my favourites as is Mandela’s return to his cell on Robben Island where he spent seventeen of his 27 years in prison.

Nelson Mandela revisits his cell on Robben Island, 1994.

Where can we see and buy more of your work?

JS: Our webpage features a range of images, books, films, films about my work and reviews, Youtube shows clips of our films and Instagram showcases a selection of work over 75-years.

Miriam Makeba posing for a Drum Cover in a downtown Johannesburg recording studio in 1955.

Sailors pub.

Backstage, New York 1979.

All photographs copyright Jürgen Schadeberg, used by kind permission.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.