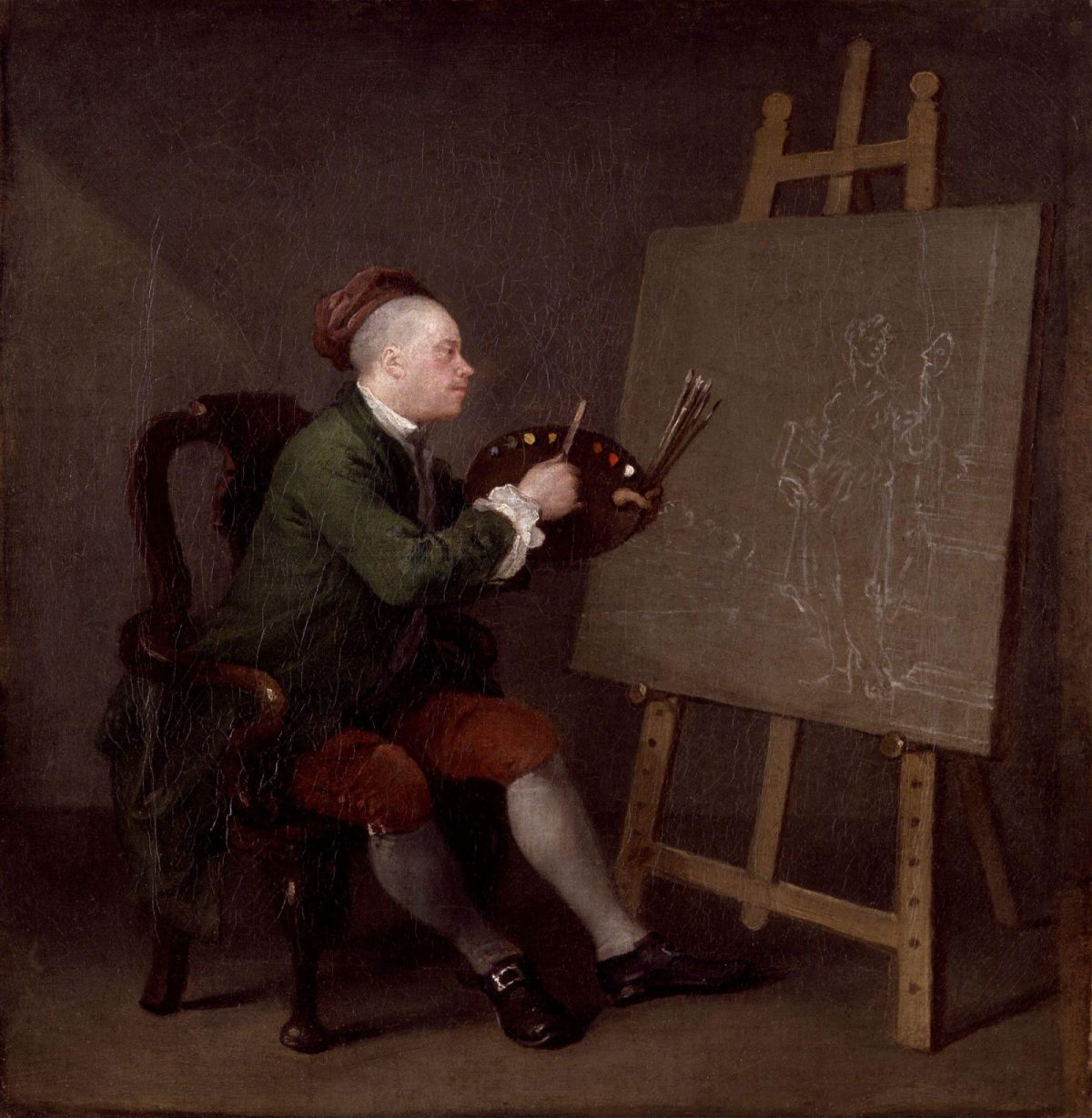

‘Hogarth Painting the Comic Muse’ (1757).

Brit Art didn’t start in the 1990s with Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin, and all that. It really began in the 1700s with William Hogarth, who was the Daddy of them all.

Hogarth (1697-1764) arrived at a time when art was becoming portable or moveable from studio to home, from studio to gallery; or through mass production, meaning art had a value in its own merit and could be bought and sold as an investment. Since the Renaissance, art was a mix of the public and propaganda. Catholic churches across Europe exhibited large canvases to reinforce their belief system. This ran in tandem with the portrait paintings of royalty in Protestant countries, of Kings and Queens who were presented in their finest jewels and ermines for those of a lower class to know their place.

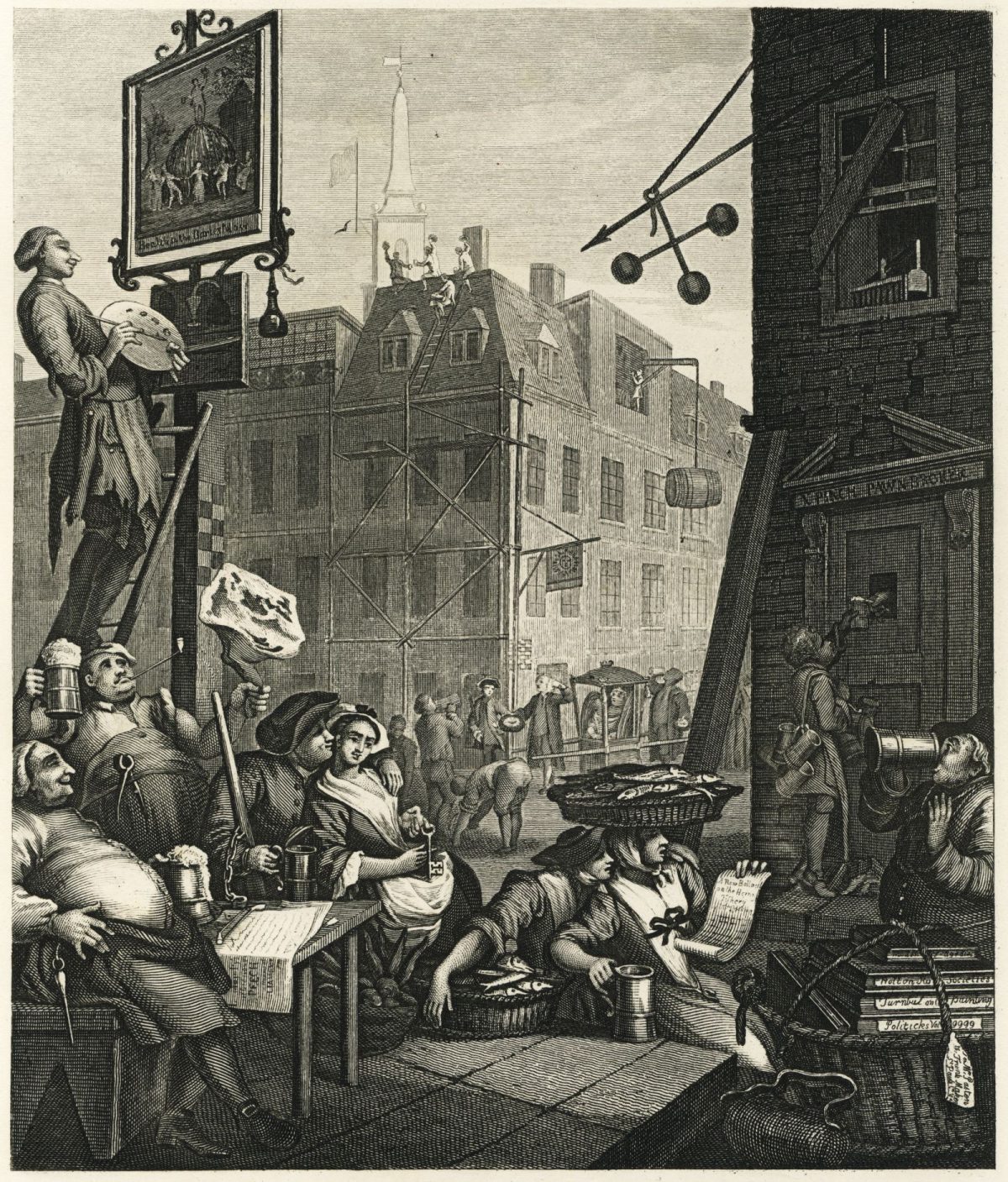

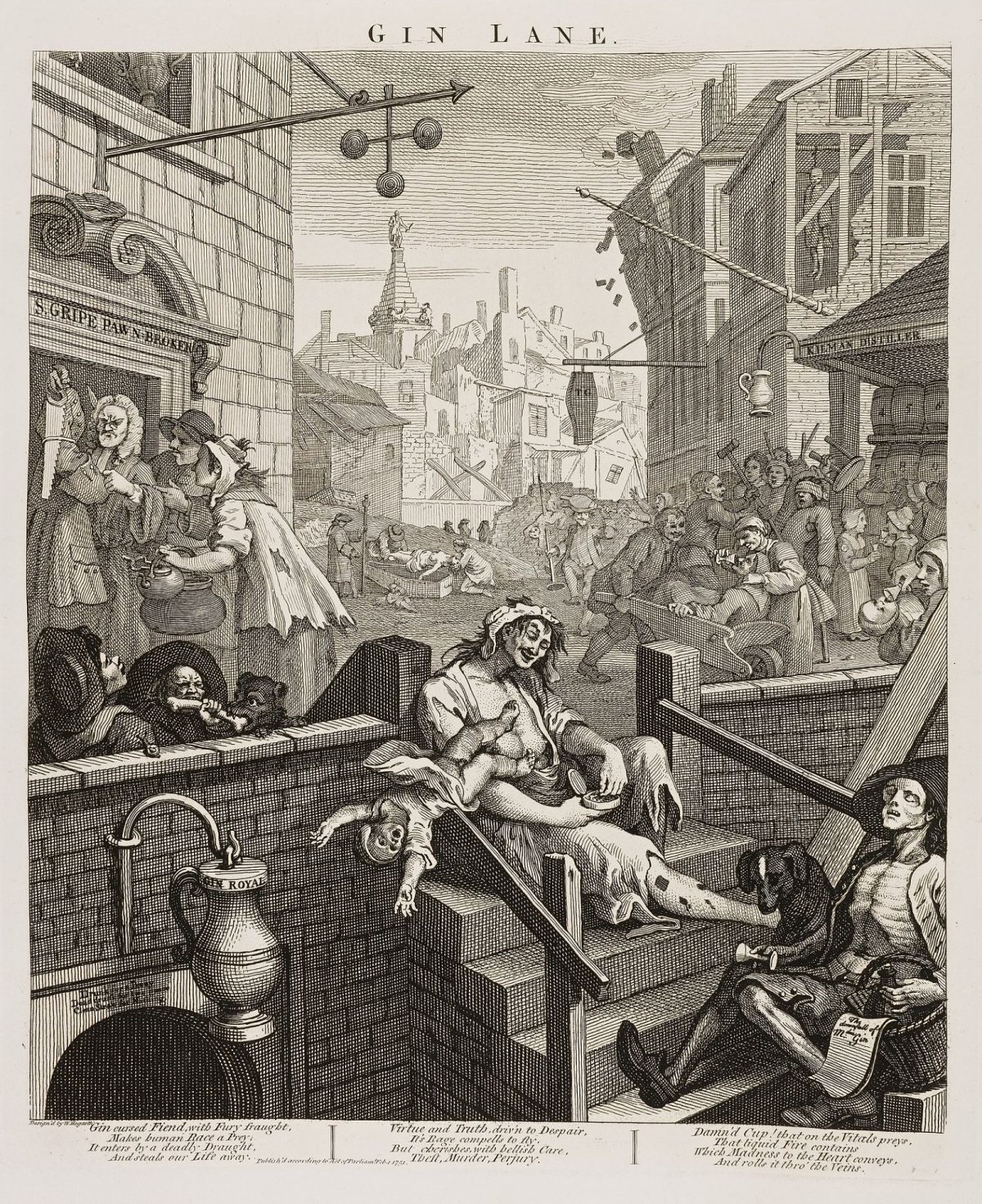

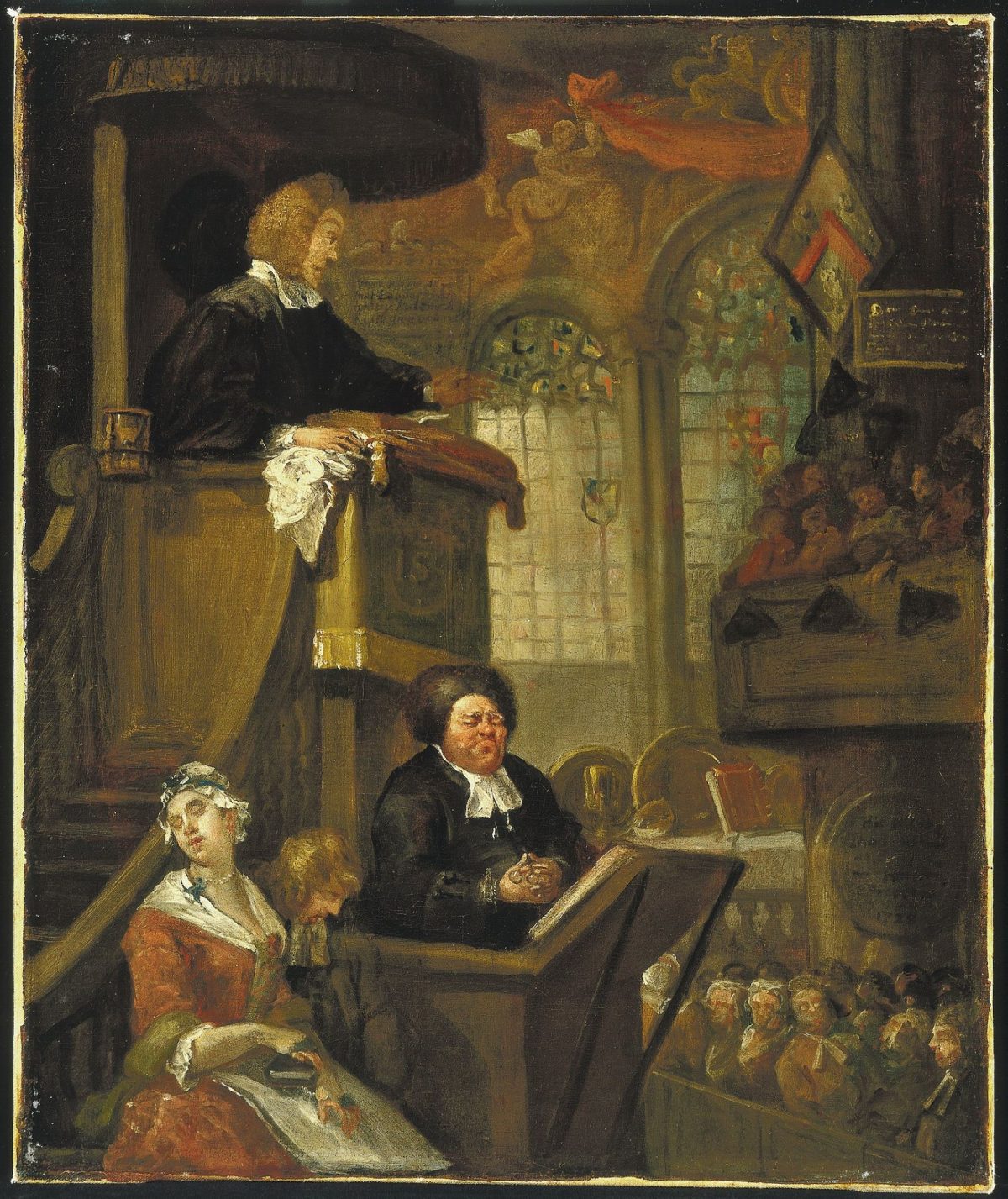

Hogarth shifted such tropes to more secular ideas. He painted morality tales that satirised British life–the drunks, the prostitutes, the politicians, the hypocrites, the befuddled, and the obese. A cast list to be found in most newspaper cartoonist’s work today.

‘Emblematical Print on the South Sea Scheme’ (1721).

Hogarth developed a style of storytelling through painting and etching which some have called the first storyboard or the first graphic / comic book artist. Both caps fit but Hogarth’s scabrous works, like The Rake’s Progress, followed on from the narrative religious work like The Stations of the Cross, which was most probably the first storyboard art.

Art was “portable” in the sense that those who could afford having their portraits painted, had a work of art as an investment, something to be treasured, and passed onto following generations. Hogarth was much sought after as a portrait painter, his career coincided with the start of the art market where art became ownable by the rising middle class and so valuable. Moreover, he worked at a time when the printing press meant his engraving work could be mass produced and sold for profit. Something Hans Holbein had understood when he produced collections of his woodcuts (The Dance of Death) in the 1520s. Hogarth’s etched tales of rakes and whores and idle fools whose lives were lost in drink, disease, madness, and death were presented as satires and warnings to the pubic. Morality was no longer dictated by religions but by man and woman.

Beer Street (1751).

This makes Hogarth sound like some thin-lipped prig, but he was a sociable old cove, who wore a turban on his head that made him look like Rab C. Nesbitt. He was friends with writers like Henry Fielding, and actors like David Garrick. He was a regular imbiber at the Rose and Crown pub, where Hogarth met with his fellow “Rosacoronians”, members of the Rose and Crown Club, who considered themselves “Eminent Artificers of this Nation”. Or pissheads to you and me….only joking.

Hogarth was born in the impoverished tightly-knotted streets around Smithfield’s Market. His father was a Latin teacher and occasional writer of textbooks. Money was scarce. Hogarth was apprenticed as an engraver. In his spare time, he wandered London’s crammed and busy streets sketching porters, busboys, street urchins, vendors, butchers, drunks, and the raggle-taggle of city life. For some obscure reason, his father opened a coffee house where patrons spoke only Latin. The business went bust and Hogarth’s father ended-up in debtor’s prison. It was an event that shaped Hogarth’s life, leaving him fearful of ending his days impoverished or imprisoned. Such fear greatly influenced his series of paintings and etchings The Rake’s Progress–in which a young man, Tom Rakewell, inherits a fortune and squanders it on prostitutes, drink, gambling, and a luxurious life, before being arrested for debt, imprisoned, and eventually confined to an asylum.

‘Gin Lane’ (1751).

Hogarth is best known for his etchings, but his paintings were revolutionary as they broke away from the subject matter and form of Renaissance art. Here were paintings that captured the bawdy tumult of city life, that pricked the pretensions of the bourgeoisie and their snobbish attitudes towards others. His use of colours and his fluid technique with a brush set painting free from the constrictions of Renaissance art. Some of his later work (The Shrimp Girl) is almost Impressionistic.

‘The Analysis of Beauty’ (1753).

Hogarth wrote a book The Analysis of Beauty in which he itemised the six points essential to good art:

1. Fitness

By which Hogarth meant: “fitness of the parts to the design for which every individual thing is formed, either by art or by nature, is first to be considered, as it is of the greatest consequence to the beauty of the whole.”

2. Variety

Or the amount of visual stimulation contained in a painting or of art–the more the better: “The shapes and colours of plants, flowers, leaves, the paintings I butterflies’ wings, shells, etc. seem of little intended use than that of entertaining the eye with the pleasure of variety.”

3. Uniformity or Regularity

How the image is presented and the uniformity of the image which allows the viewer to “delight” in its irregular features.

4. Simplicity

As in “simplicity gives beauty even to variety, as it makes it more easily understood…”

5. Intricacy

Keep it interesting for the viewer so “the eye has this sort of enjoyment in winding walks, and serpentine rivers, and all sorts of objects, whose forms…are composed principally of what, I call, the waving and serpentine lines.”

6. Quantity

Fill your etching or painting with enough objects or events to keep the viewer engaged. Too much and it is case. The right amount and the work will last.

‘Engraving of John Wilkes’ (1763).

Hogarth’s work covered portraiture, morality, Biblical work, satire, engravings, and if that weren’t enough, he also wrote several books on Art and its meaning. He was a revolutionary artist at a time of great change in society, and in many ways William Hogarth is the Father of British Art.

‘The Bench’ (1758).

‘The Sleeping Congregation’ (1728).

‘Before’ (1731).

‘After’ (1731).

‘The Rake’s Progress: The heir’ (1732-34).

‘The Rake’s Progress: The Levée’ (1732-34).

‘The Rake’s Progress: The Orgy’ (1732-34).

‘The Rake’s Progress: The Arrest’ (1732-34).

‘The Rake’s Progress: The Marriage’ (1732-34).

‘The Rake’s Progress: The Gaming House’ (1732-34).

‘The Rake’s Progress: The Prison’ (1732-34).

‘The Rake’s Progress: The Madhouse’ (1732-34).

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.