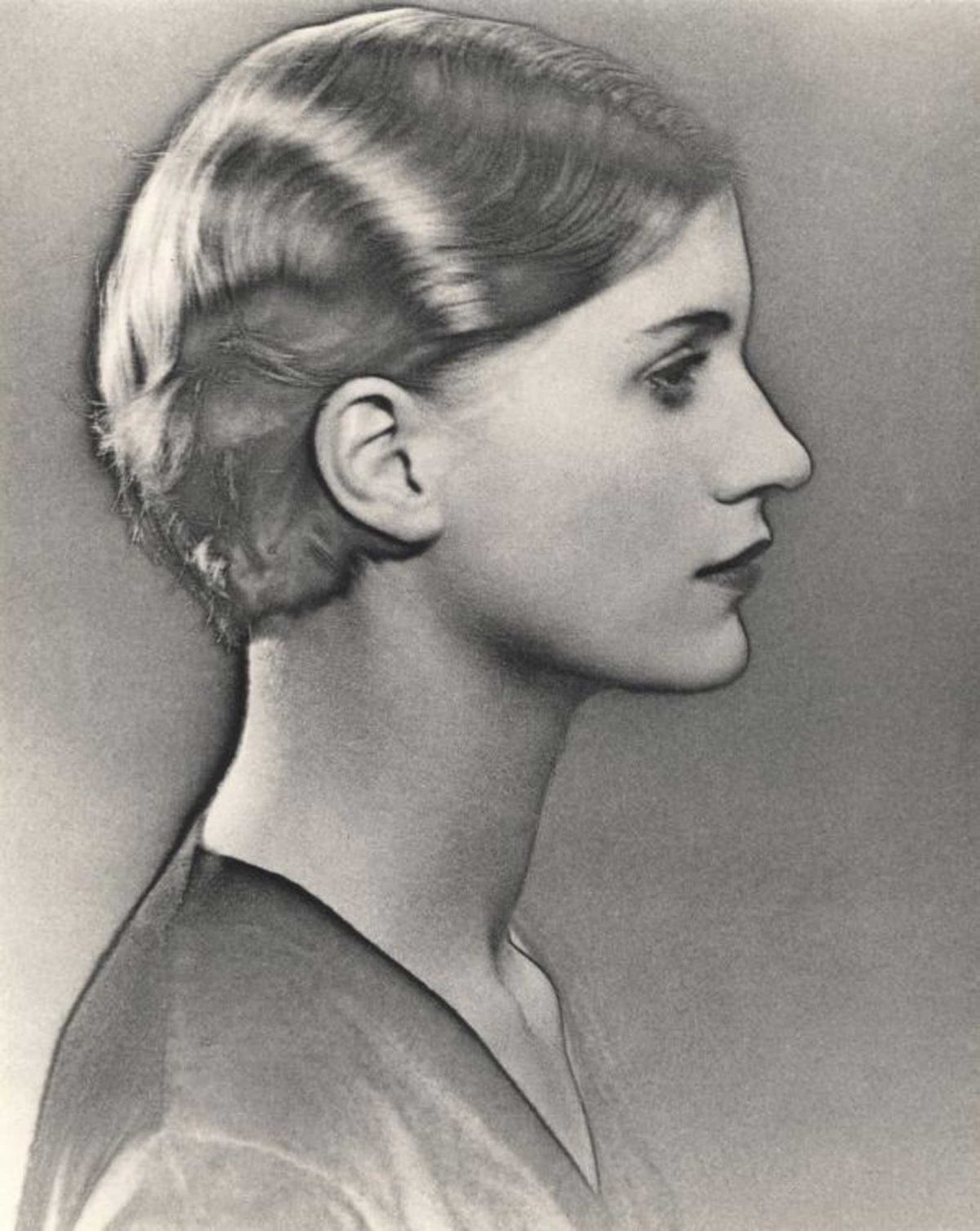

The life of model, photographer, and artist Lee Miller is so extraordinary it’s almost hard to believe one person lived it all. Born in Poughkeepsie, NY in 1907, Miller moved to New York City after a traumatic childhood. She was 19, it was the height of the jazz age, and she was promptly discovered by Condé Nast after he pulled her out of the path of an oncoming truck. In the following year, Miller became one of the most prominent faces of Vogue, gracing a famous cover—in blue flapper hat and pearls—in an illustration by Georges Lepape.

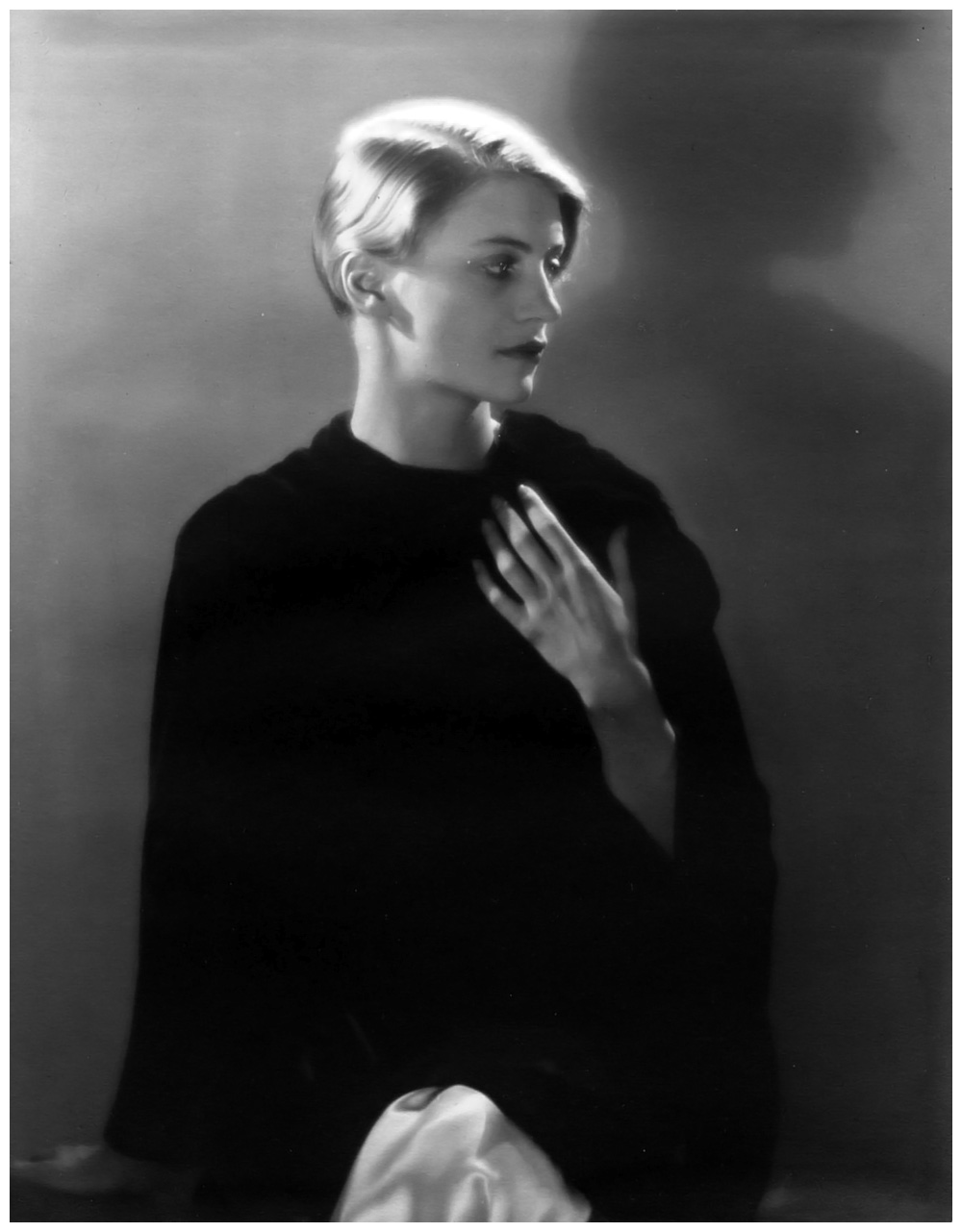

But Miller had other ambitions, and when she was unceremoniously shut out of the fashion industry after one of her images was licensed to Kotex, she “went back to art,” says curator Philip Prodger, and “was recommended to meet Man Ray.” In 1929, she moved to Paris and “just presented herself at the doorstep” of the Surrealist American photographer and painter. After some persistence on her part, he took her on as an assistant, and the two became lovers and artistic collaborators.

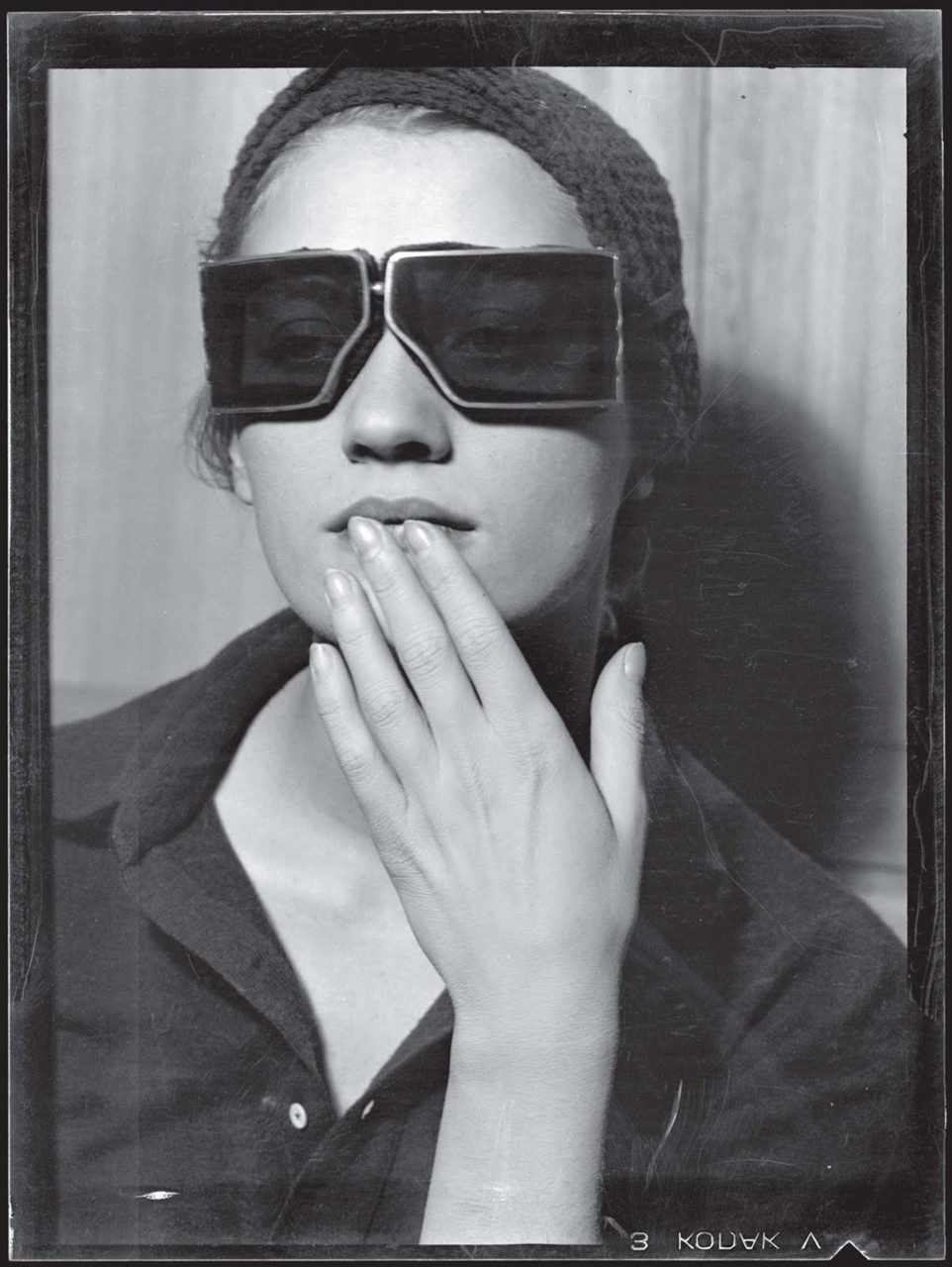

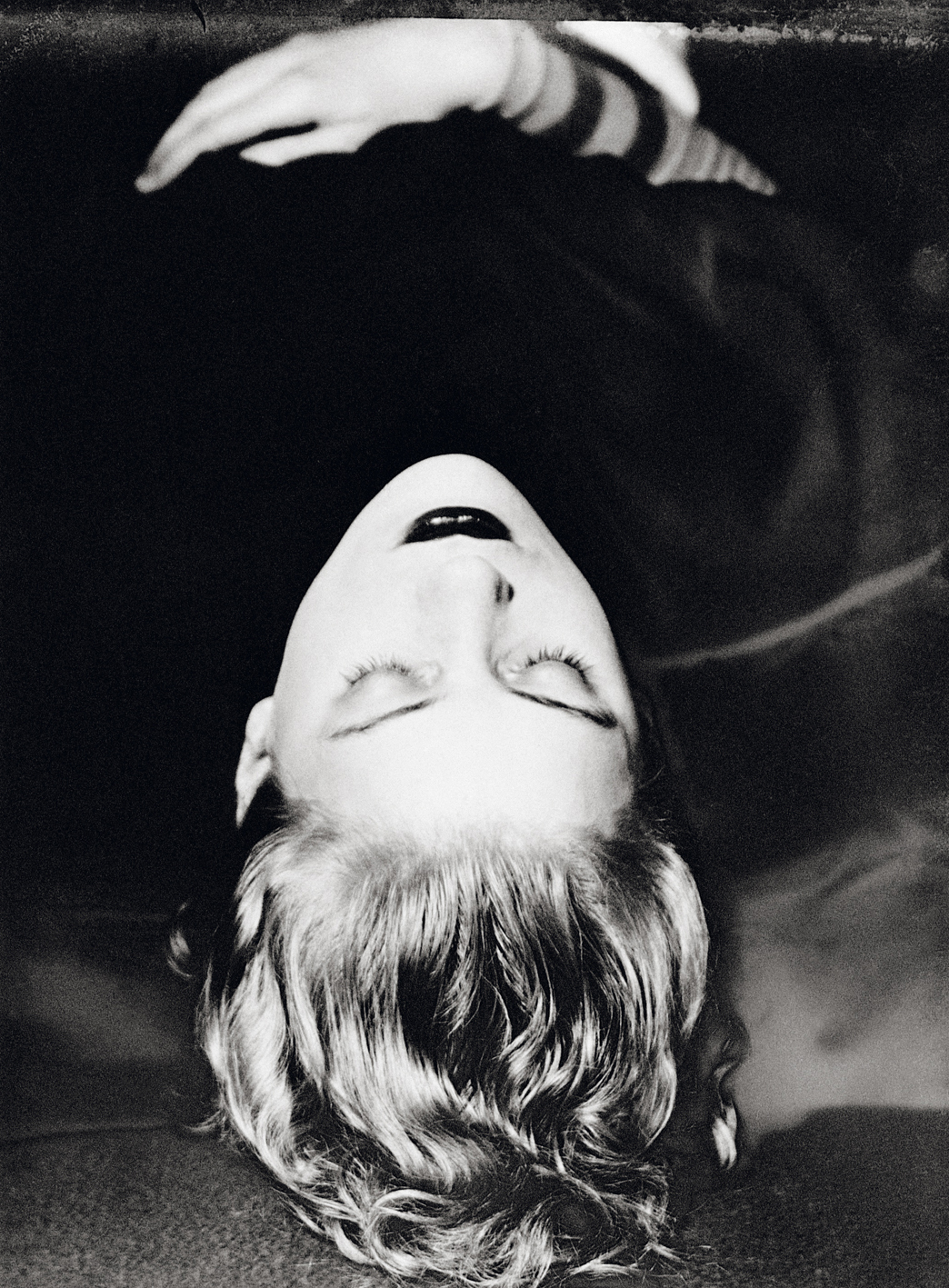

Miller is sometimes thought of as just one of Man Ray’s models and muses, but she took an active role in the creation her portraits, discovering the process of solarization used in several mages (which he called “rayographs”), and taking on some of his commissions in his place to give him time to paint. She became well-known as an artist and forceful personality in her own right in the Parisian circle of artists like Picasso, who painted her and with whom she formed a creative friendship.

When Miller arrived in Paris, said her future husband, painter Roland Penrose, “she had been a Surrealist for some time—before the movement even had a name—because she had that determination to pursue her life free of the constraints of society which the Surrealists were already rebelling against…. The Surrealist movement was going in tremendous force, and she was ready-made for it, and it for her.”

But she would return to the fashion world and to Vogue, leaving Man Ray in Paris in 1932 and setting up her own photography studio in New York. While she continued to model while managing high-profile clients and exhibiting her work in galleries she found her ultimate power behind the camera; “I’d rather take a picture than be one,” she said. That confidence and skill led her, at 32, to become “one of only four female photographers accredited to the US Armed Forces” when war broke out in 1939, as Lucy Davies writes at The Telegraph.

As a war correspondent for Condé Nast Miller teamed up with Life photographer David Scherman (who captured the fierce image of her above) to get access to the front lines of the fighting. It was a “role for which she was almost entirely unprepared, in terms of both formal training and combat experience,” but which she threw herself into completely, producing what i-D’s Lily Bonesso calls “some of the most moving war photography of the time.”

What was most inspired… was Lee’s documentation of the unarmed warriors — the women who were left behind and had to keep their countries going while the boys were away. With tact and composure, Lee depicts these women as strong individuals, not figures who needed protection or pity. You can tell these women feel comfortable around her, and this gave her access to areas no male photographer could have ventured into.

She also documented women in combat, like the Polish pilot just below. Miller got up close to the killing and photographed the liberation of Dachau, writing “I IMPLORE TO TO BELIEVE THIS IS TRUE” to her Vogue editors in 1945. “Vogue didn’t doubt her,” Bonesso comments, “the images spared nothing.”

That same year, Scherman photographed her in Hitler’s bathtub in Munich, on the day the Führer committed suicide in Berlin, an image “more disturbing than Dali’s lobster telephone,” writes Laura Freeman. “Vogue didn’t know what to do with the bath photograph,” so “they buried it,” notes curator Hilary Floe, “printed tiny in the back matter.”

The image is consistent with her form of protest against female objectification, forcing viewers to confront classical images of beauty and desire in the most jarring of settings and recalling a photograph she took in 1929 in a Paris hospital of a breast removed during a mastectomy, placed on plate with a table setting. “As a fashion model,” says Miller’s son Antony Penrose, “Lee was used to people looking at her as a thing rather than as a person.” It was an experience she tried to control as an artist’s model. “The Surrealists had a particularly proprietorial view of women,” says Penrose, “and they, as much as anyone, are what Lee was rebelling against.”

After Miller’s death in 1977, her son discovered 60,000 original negatives and 20,000 prints and contact sheets. You can see thousands of her photographs at a huge online archive. Just below, see more of Man Ray’s portraits of Miller and, further down, more of her wartime images.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.