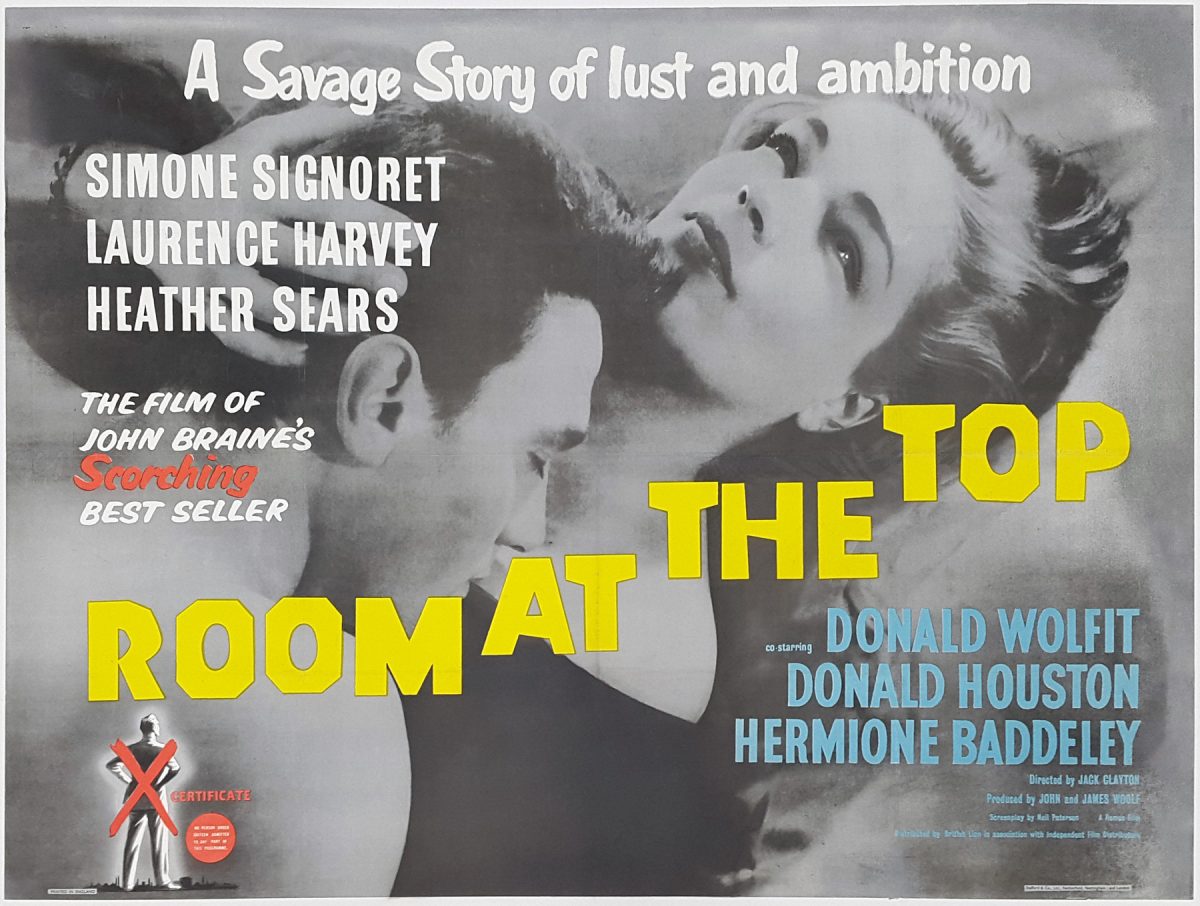

Room at the Top directed by Jack Clayton and released in 1957

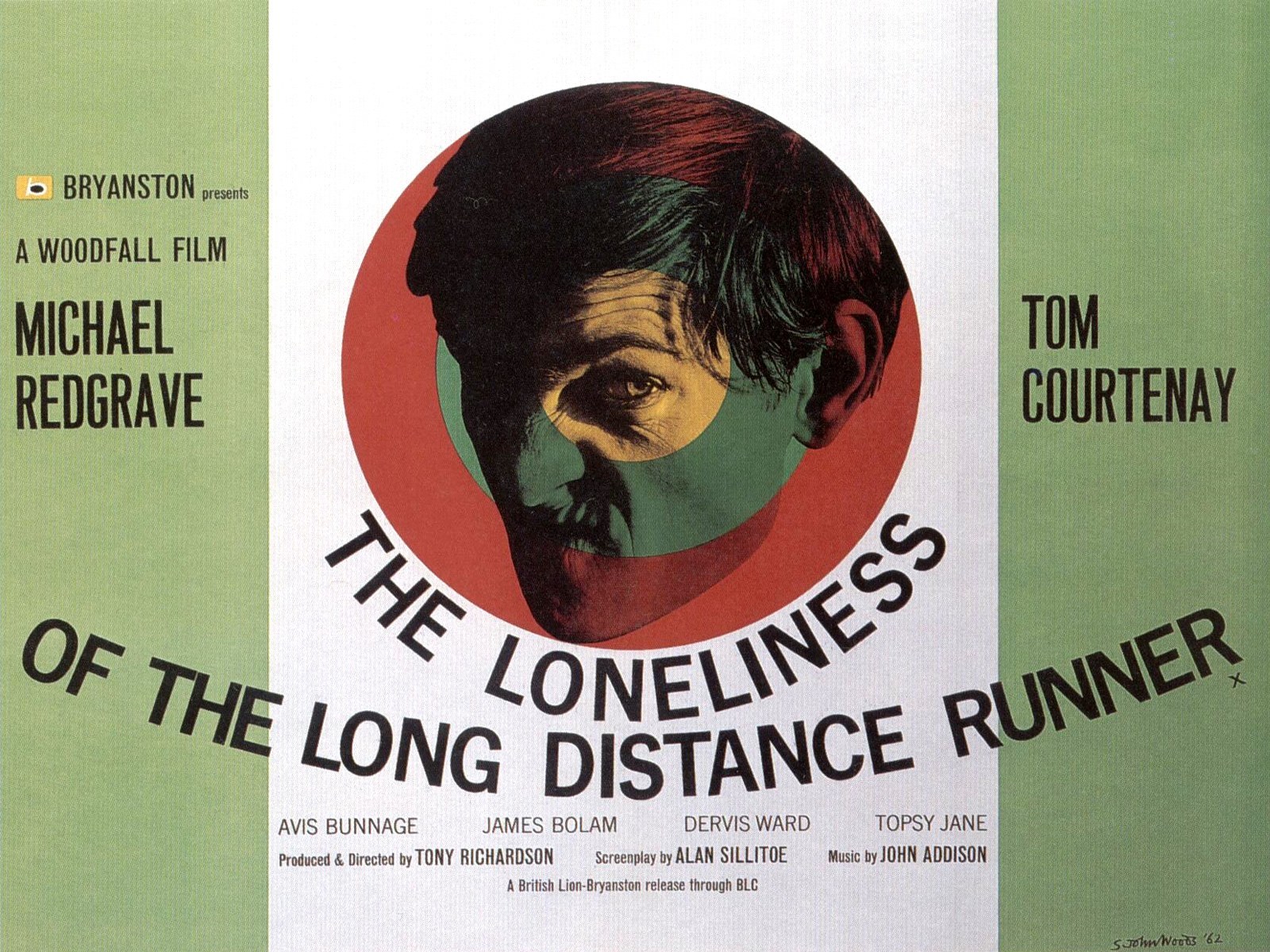

THE so-called British New Wave lasted only a few years – say from about 1959 to 1963 and it consisted of little more than seven or eight films. Most of the them adapted from books or plays written by young contemporary writers such as John Braine, Alan Sillitoe and Shelagh Delaney. A slight relaxation of censorship by the late fifties together with the invention of lightweight portable cameras and faster film stock made it easier for directors such as Tony Richardson, Karel Reisz and Lindsay Anderson to make films on location away from London and the usual film studios. Just as their contemporaries across the channel had done the British cinema-goers found this all a cinematic breath of fresh air.

Room at the Top

“Nobody blames you,” to which Joe Lampton gives the bitter reply: “Oh, my God that’s the trouble.”

Room at the Top the first of the genre was released in 1959 and was given an ‘X’ certificate. It wasn’t admitted of course but the main reason was that ‘shockingly’ it featured a woman on screen admitting that she had enjoyed sex. Initially the distributors refused to touch it but the ABC chain took a chance and the film went on to become a critical and commercial hit, paving the way for the rest of the ‘kitchen sink’ British New Wave that soon followed. The Guardian wrote of Room at the Top:

Here for once is a film which wears an “X” certificate as it should be worn. Not as a deliberate titillation but as a sign that it is not a film for the young – or for that matter for the stupid.

Room at the Top novel with a cover designed by John Minton

John Braine by David Moore in 1958

Room at the Top poster – the most daring adult film in a decade!

Although he published twelve works of fiction during his life it’s fair to say that for most people John Braine is little remembered today for anything but his first novel Room at the Top published in 1957. He was born in a small terraced house near the Westgate area of central Bradford in 1922. The family later moved to the suburb of Thackley when his father got a job at Esholt’s Sewage works. The Yorkshire Post described Thackley of the time as “a grim satellite of industrial Shipley, just the sort of place his main Room at the Top character Joe Lampton came from, “where the snow seemed to turn black almost before it hit the ground.”‘

Braine left St. Bede’s Grammar School at sixteen and worked in a shop, a laboratory and a factory before becoming, after the war, a librarian in Bingley, a small town five miles up the Aire Valley. Braine came up with the idea for his first novel while being treated for tuberculosis in a hospital near the Yorkshire Dales town of Grassington. He stated that his favourite author was Guy de Maupassant and that Room at the Top was based on Bel Ami, but that “the critics didn’t pick it up”.

Vernon Johnson of the Guardian reviewed Braine’s first novel in March 1957:

In the small Yorkshire town where most of the action takes place life is fought out according to a simple formula: to be happy you need a really large lump of money; to get this money you have to fight like an all-in wrestler; therefore you are a fool and a weakling if you fail to gouge, trip, bite, and, if need be, throw the referee out of the ring. Next to money in importance in this unpretty world is class.

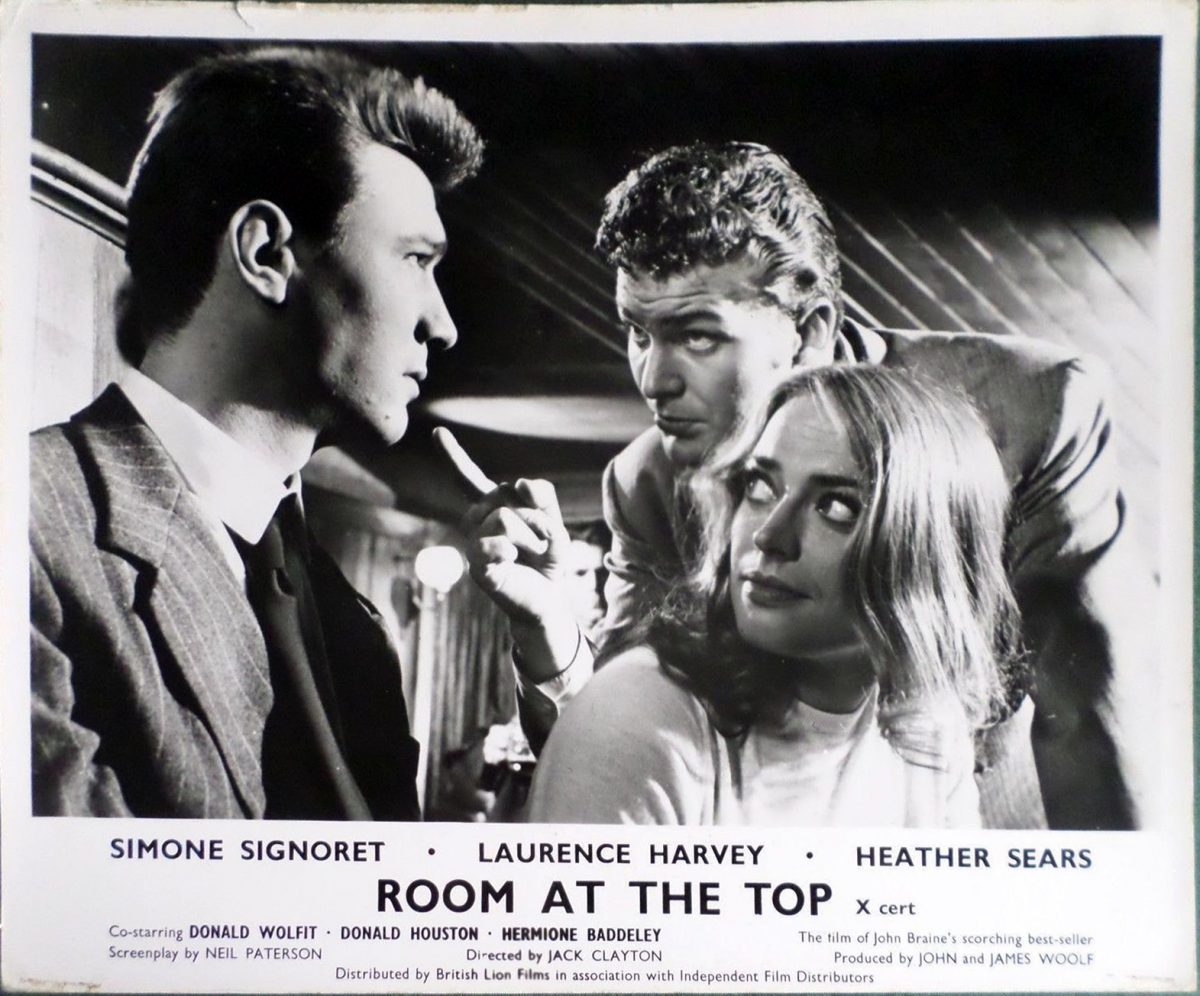

Room at the Top lobby card

Man at the Top was a British ITV TV show that aired for 23 episodes between 1970 and 1972. The series depicted the same character Joe Lampton, the protagonist of John Braine’s novel Room at the Top and of two subsequent films, Room at the Top and Life at the Top. In 1973 a spin-off film from the series, Man at the Top, was released.

Look Back in Anger

Jimmy Porter: Ladies and gentlemen, a little recitation entitled ‘she was only a gravediggers daughter but she loved lying under the sod’.

Four months before the Suez crisis, the moment in history when a begrudging, drizzly and grey Britain came to realise that it wasn’t really a super-power any more, the newly re-opened Royal Court Theatre, situated on the east side of Sloane Square in Chelsea, premiered the first play by a 26 year old actor called John Osborne.

Look Back In Anger was written in seventeen days while sitting in a deckchair on Morecambe pier . The legend is, of course, that Osborne’s play was an over night success and almost by the next morning the Terrence Rattigan and Noel Coward drawing-room dramas were all replaced by plays set in drab working working class northern bed-sits.

Original production of Look Back in Anger

It’s said that on the first night of Look Back In Anger the first glance of Alison Porter’s ironing board on stage drew actual loud gasps from the audience. The Daily Mail’s Cecil Wilson wrote that the beauty of Mary Ure, who played Alison, was “frittered away” on a pathetic wife, who, “judging by the time she spends ironing, seems to have taken on the nation’s laundry”. Terrence Rattigan himself, although persuaded not to leave at the interval by a friend, said on leaving the theatre:

I think the writer is trying to say: ‘Look how unlike Terence Rattigan I am, Ma!

In reality the play was initially seen as a failure. After the first night the Guardian wrote: “The author and actors do not persuade us that they ‘speak for’ a new generation.” While the London Evening Standard called the play nothing short of “a self-pitying snivel”. The next day the director of the play Tony Richardson and Osborne sat in the little coffee shop next to the Royal Court Theatre utterly depressed. Richardson broke the silence, and said:

But what on earth did you expect? You didn’t expect them to like it, did you?

Although the play was generally initially dismissed by most of the critics, a prescient 39 year old Kenneth Tynan wrote in the Observer –

All the qualities are there, qualities one had despaired of ever seeing on the stage … I doubt if I could love anyone who did not wish to see Look Back in Anger.

John Osborne (right) and Kenneth Haigh outside the Royal Court theatre in 1956. Photograph- Frank Pocklington.

Kenneth Haigh with Mary Ure in the 1956 production of Look Back in Anger

1956 ‘Look Back in Anger’ rehearsal Royal Court Theatre

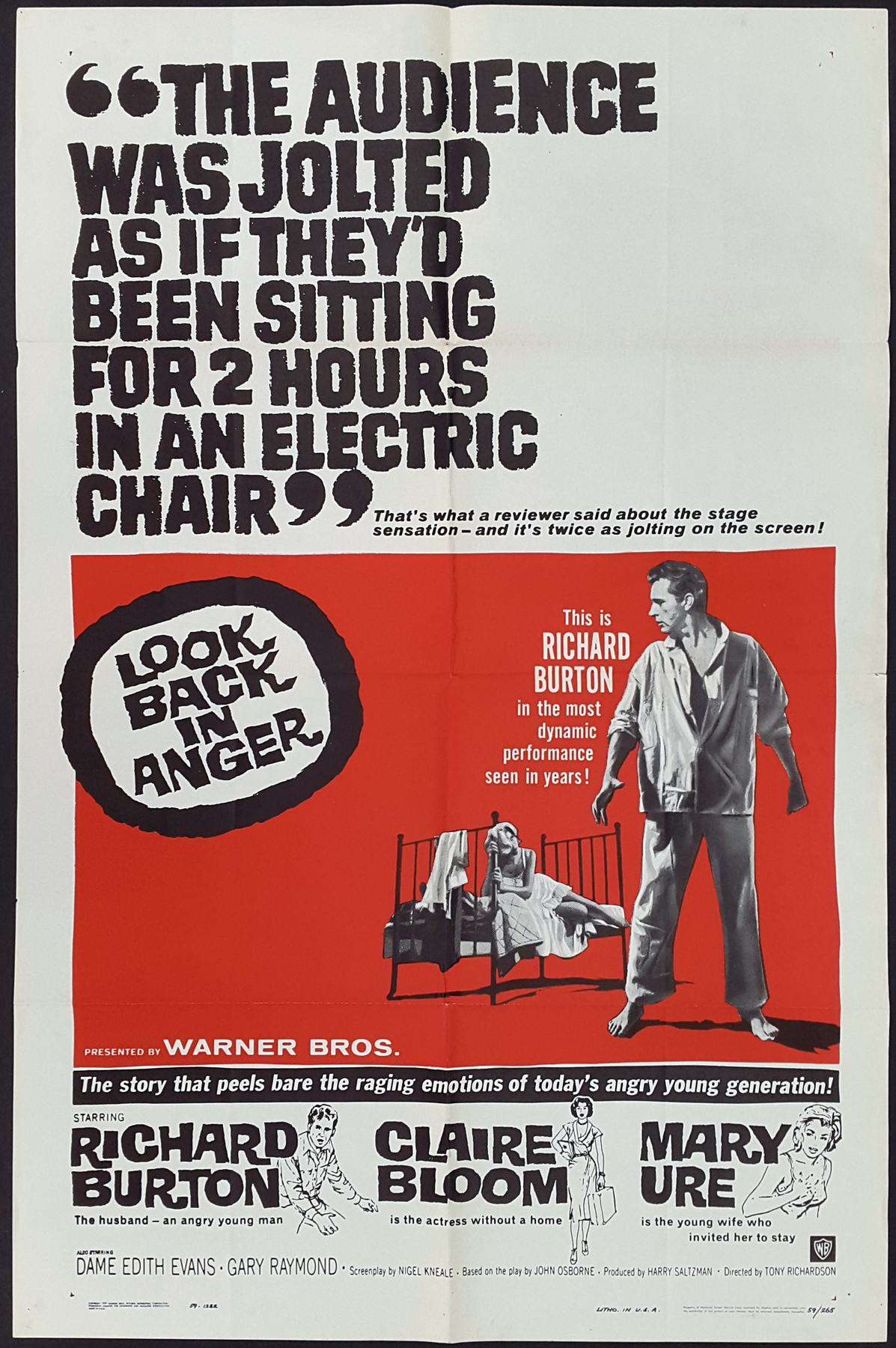

Look Back in Anger initially took very little money and the production was seen pretty much as a miserable failure. A few weeks into the run, however, the BBC decided to broadcast a short excerpt of the play one evening. The listeners liked what they heard, decided to go and see the play for themselves and takings immediately doubled at the box office. The effect snowballed and the play eventually transferred to the West End, subsequently to Broadway and was made into a film in 1958 starring Richard Burton. It certainly wasn’t overnight but Osborne had now become a very famous angry young man indeed.

Osborne left his first wife Pamela Lane shortly before the opening of Look Back In Anger, and subsequently married Mary Ure the leading actress in the play and the film. They lived in a house in Woodfall Street just off the Kings Road a few hundred yards from The Royal Court Theatre. It was a marriage that would only last five years and his love life was, by the early sixties, extremely complicated. He was on holiday in the South of France with his mistress the beautiful flame-haired dress designer Jocelyn Rickard in 1961, while at home Mary Ure was giving birth to a son (to be fair it probably wasn’t Osborne’s). At the same time, in Italy, the journalist Penelope Gilliatt, and future mother of his daughter, received a charming marriage proposal by letter:

Will you marry me? It’s risky, but you’ll get fucked regularly.

Tony Richardson and Richard Burton by Robert Penn

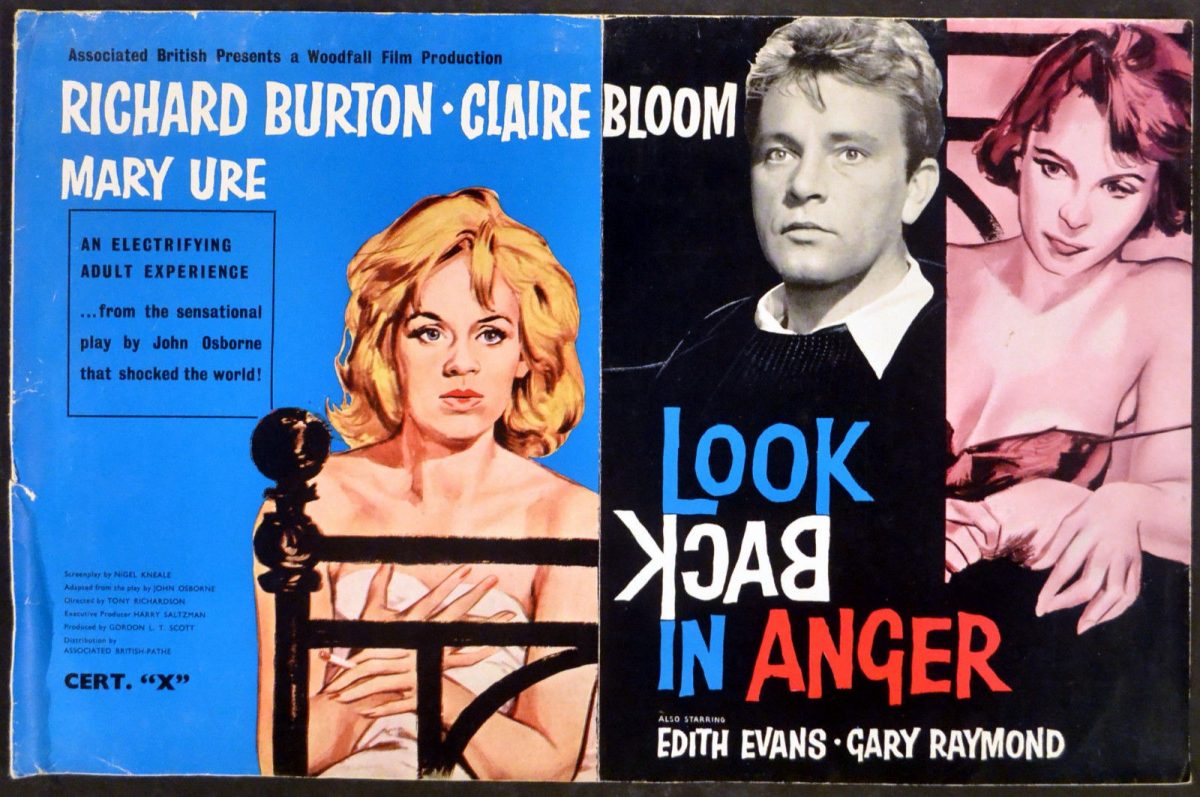

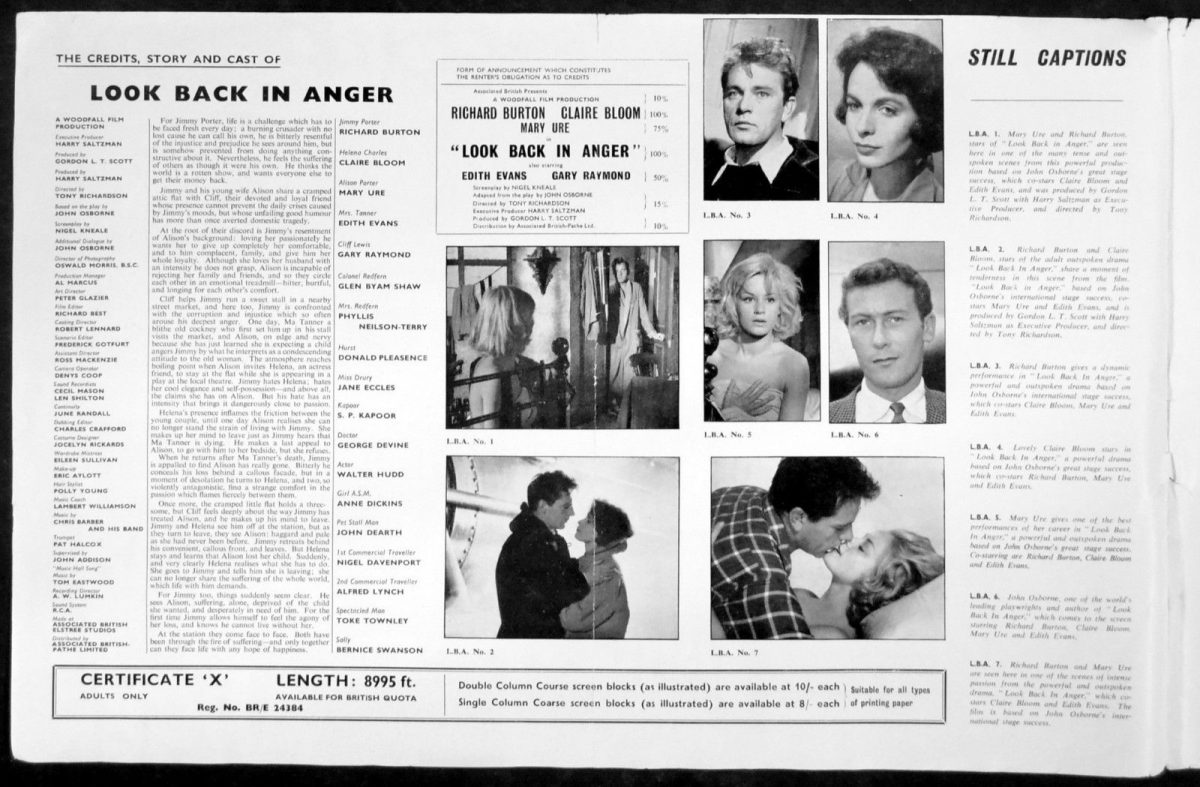

Following the eventual success of the play the film version starring Richard Burton, Claire Bloom, and Mary Ure and directed again by Tony Richardson was shot in 1958 and released in 1959. The action is taken out of Jimmy and Alison’s one room flat to a street market, a cemetery, a pub, a cinema and a railway station. The Manchester Guardian wrote at the time, and it was probably right, that ‘strictly speaking, John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger should never have been filmed unless the director had the courage to keep his camera inside that dingy bed-sitting room’.

After the film was released Tynan again wrote why he thought Look Back in Anger was important:

Most of the critics were offended by Jimmy Porter, but not on account of his anger; a working-class hero is expected to be angry. What nettled them was something quite different: his self-confidence. This was no envious inferior whose insecurity they could pity. Jimmy Porter talked with the wit and assurance of a young man who not only knew he was right but had long since mastered the vocabulary wherewith to express his knowledge.

LOOK BACK IN ANGER 1959 Richard Burton, Claire Bloom, Mary Ure UK CAMPAIGN BOOK

LOOK BACK IN ANGER 1959 Richard Burton, Claire Bloom, Mary Ure UK CAMPAIGN BOOK page 2

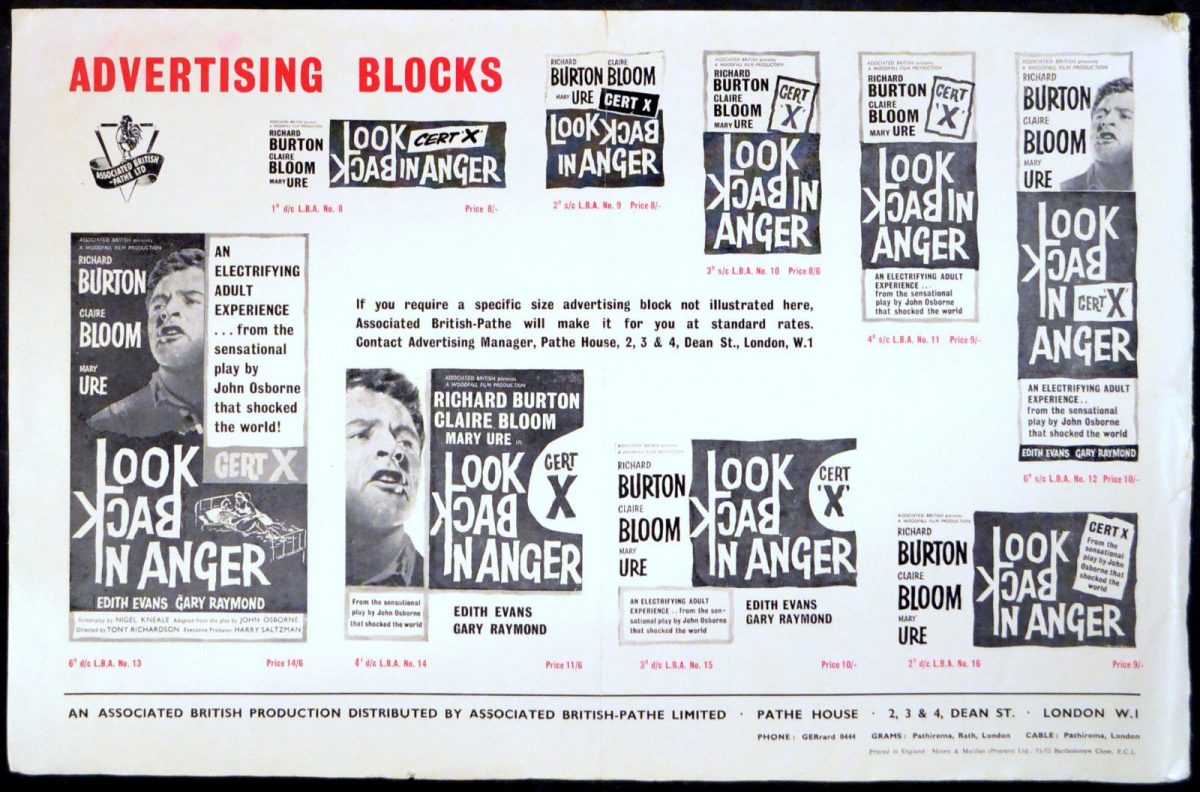

LOOK BACK IN ANGER 1959 Richard Burton, Claire Bloom, Mary Ure UK CAMPAIGN BOOK page 3

LOOK BACK IN ANGER 1959 Richard Burton, Claire Bloom, Mary Ure UK CAMPAIGN BOOK page 4

‘Saturday Night and Sunday Morning’ and ‘The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner’ by Alan Sillitoe

Born in Nottingham during the spring of 1948, Alan Sillitoe’s childhood was spent in a tiny terraced house in Nottingham with a father who was almost always unemployed – “we lived in a room whose four walls smelled of leaking gas, stale fat and layers of mouldering wallpaper.” After leaving school with no qualifications he started working as a labourer and then, still only fourteen, he was employed at the local Raleigh Bicycle Factory. From 1946 to 1949 he worked as an RAF wireless operator in Malaya after lying about his age during WW2 to join the Air Training Corps. Getting home it was found he had tuberculosis during which time he started writing.

Between 1952 and 1958 he travelled in France and Spain with the poet Ruth Fainlight, whom he married in 1959, and was encouraged to write by the poet Robert Graves whom he met in Majorca.

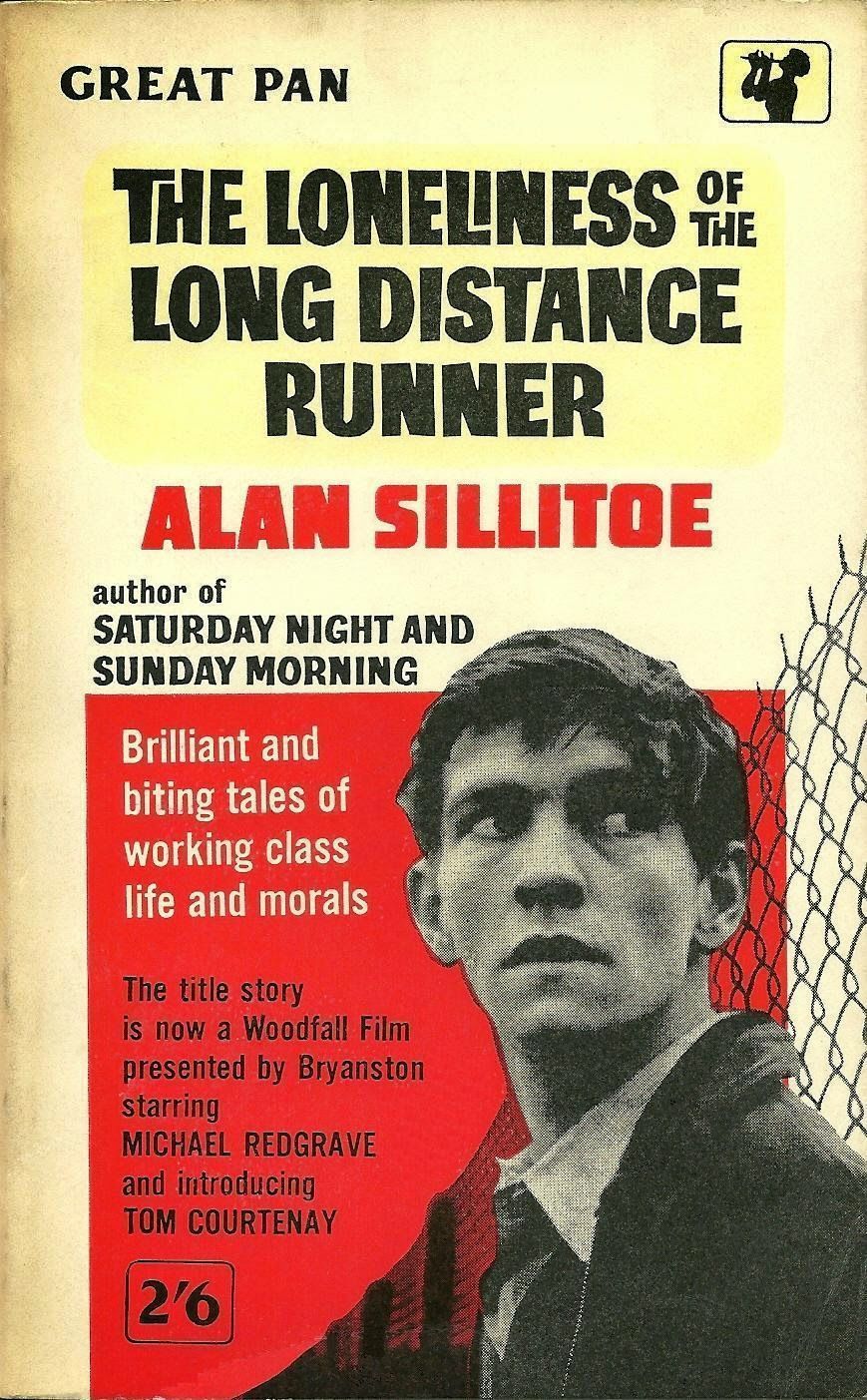

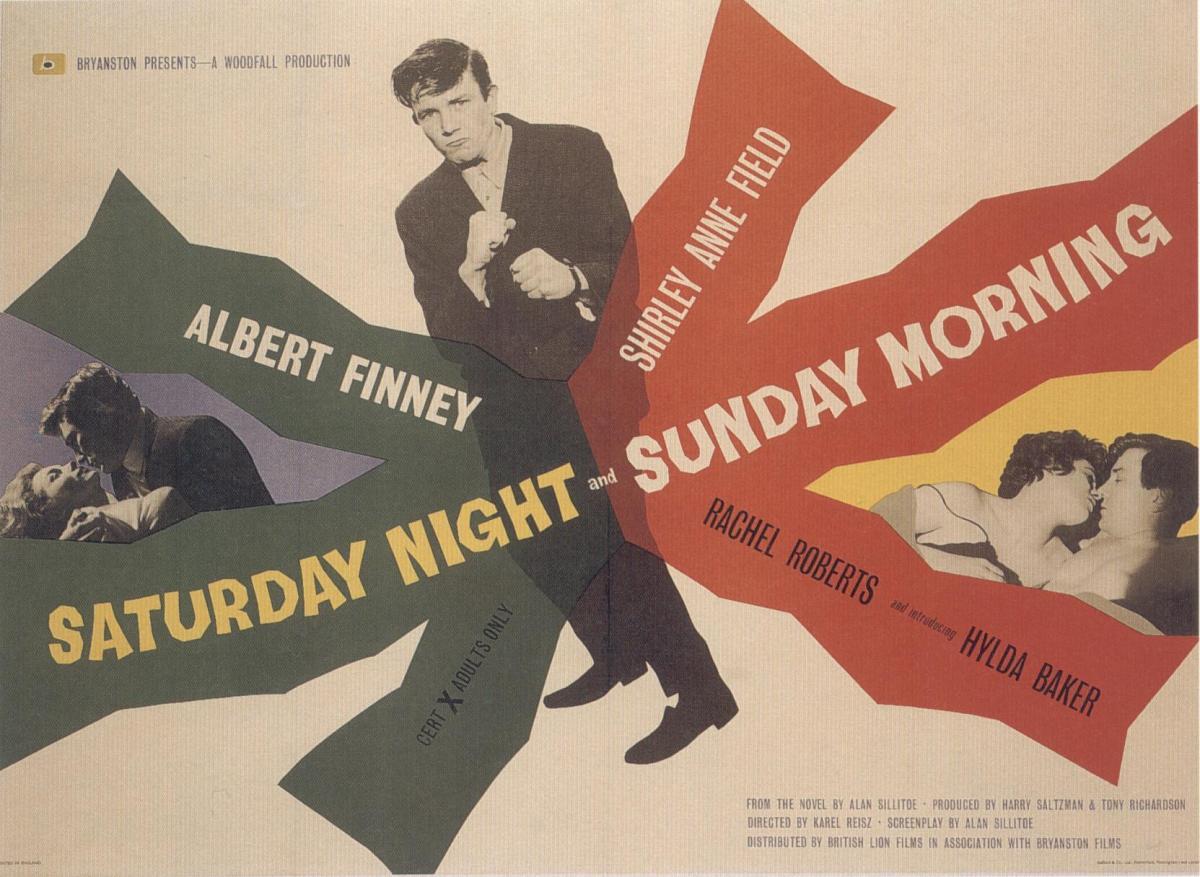

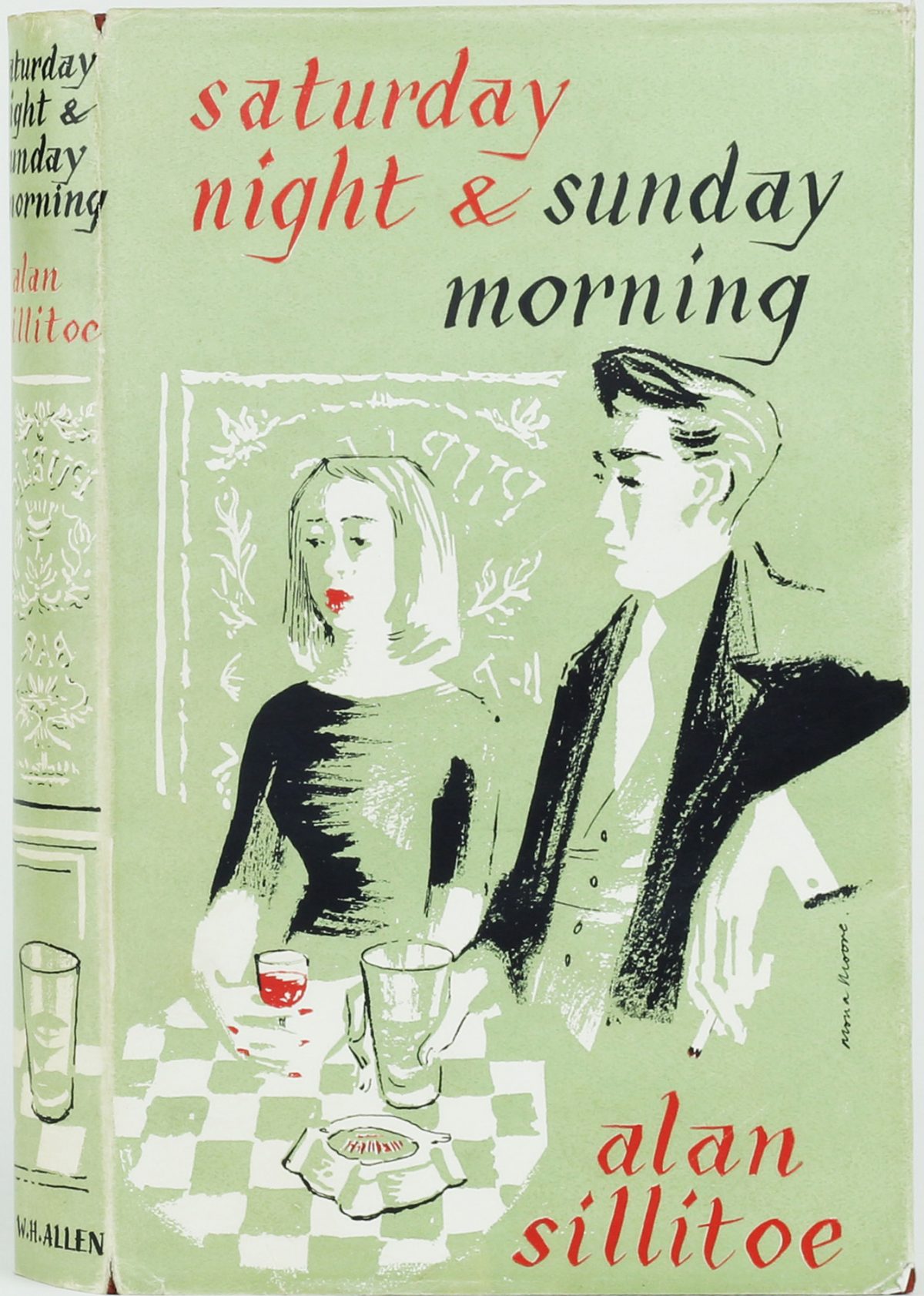

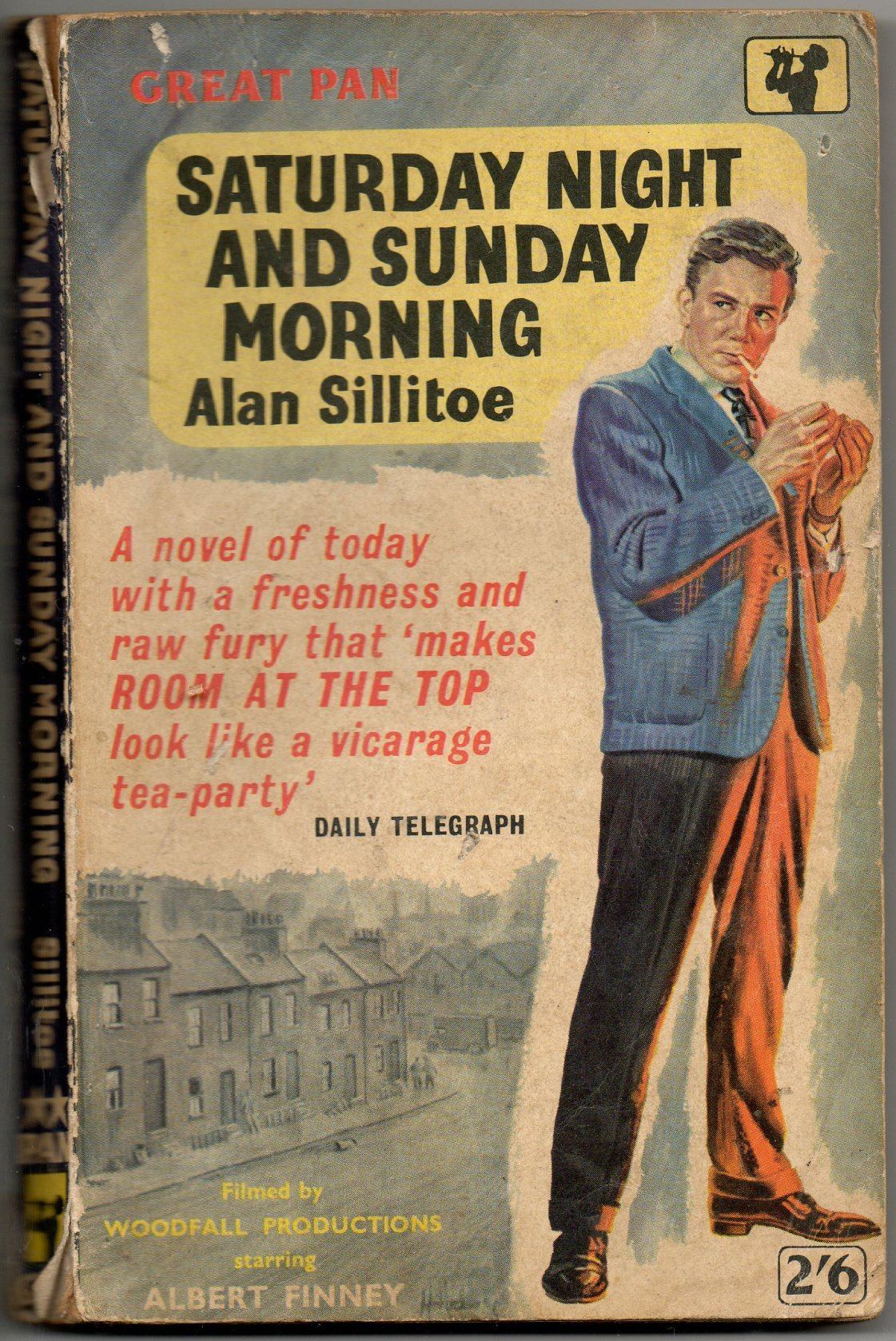

Sillitoe published his first volume of poetry, Without Beer or Bread, in 1957, soon followed in 1958 by Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, an extraordinary portrayal of working-class masculinity set in Nottinghamshire. Two years later the well-reviewed book was turned into a film starring Albert Finney. The title story of his next book, The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner, is narrated by Colin Smith a rebellious and angry Borstal boy who after finds he has talent as a cross-country runner. Although he enjoys running he purposely throws away the chance of winning a long-distance championship to spite the governor and “they” – the police, the courts, people of authority that cause his life to be a misery:

No, I won’t get them that cup, even though the stupid Tash-twitching bastard has all his hopes on me. Because what does his barmy hope mean? I ask myself. Trot-trot-trot, slap-slap-slap, over the stream and into the wood where it’s almost dark and frosty-dew stings my legs.

Again the short story soon became a film 1961 starring Tom Courtenay. Ken Russell wrote of Saturday Night and Sunday Morning and The Loneliness of the London-Distance Runner when they were released on DVD in 2009:

These breakthrough movies of the early 1960s were about the hopes, fears and foul-ups of young working class fellows entering adulthood in a culture that held no rewards for the unique vitality and emerging vision, but only drudgery and repetition.

Topsy Jane in The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962)

Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, 1960.

Saturday Night and Sunday Morning Pan Paperback.

Shirley Anne Field ad Doreen and Albert Finney. as Arthur Seaton.

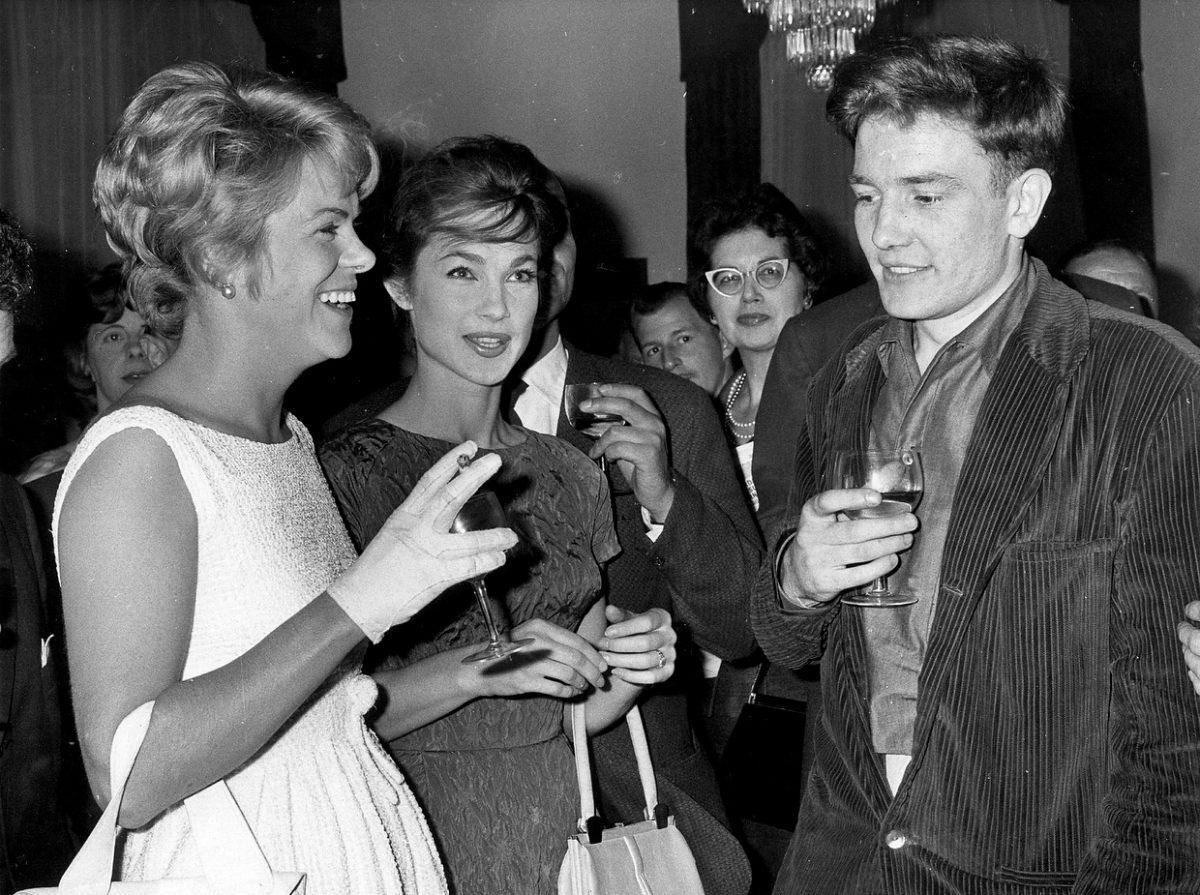

Young actor Albert Finney talks to his co-stars in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, Shirley Anne Field and Rachel Roberts, at a social event in Belgrave Square, London on August 11, 1960. (Photo by Evening Standard/Getty Images)

English actor Albert Finney with the singer Alma Cogan at the ‘Talk of the Town’ restaurant on January 31, 1961. (Photo by Evening Standard/Getty Images)

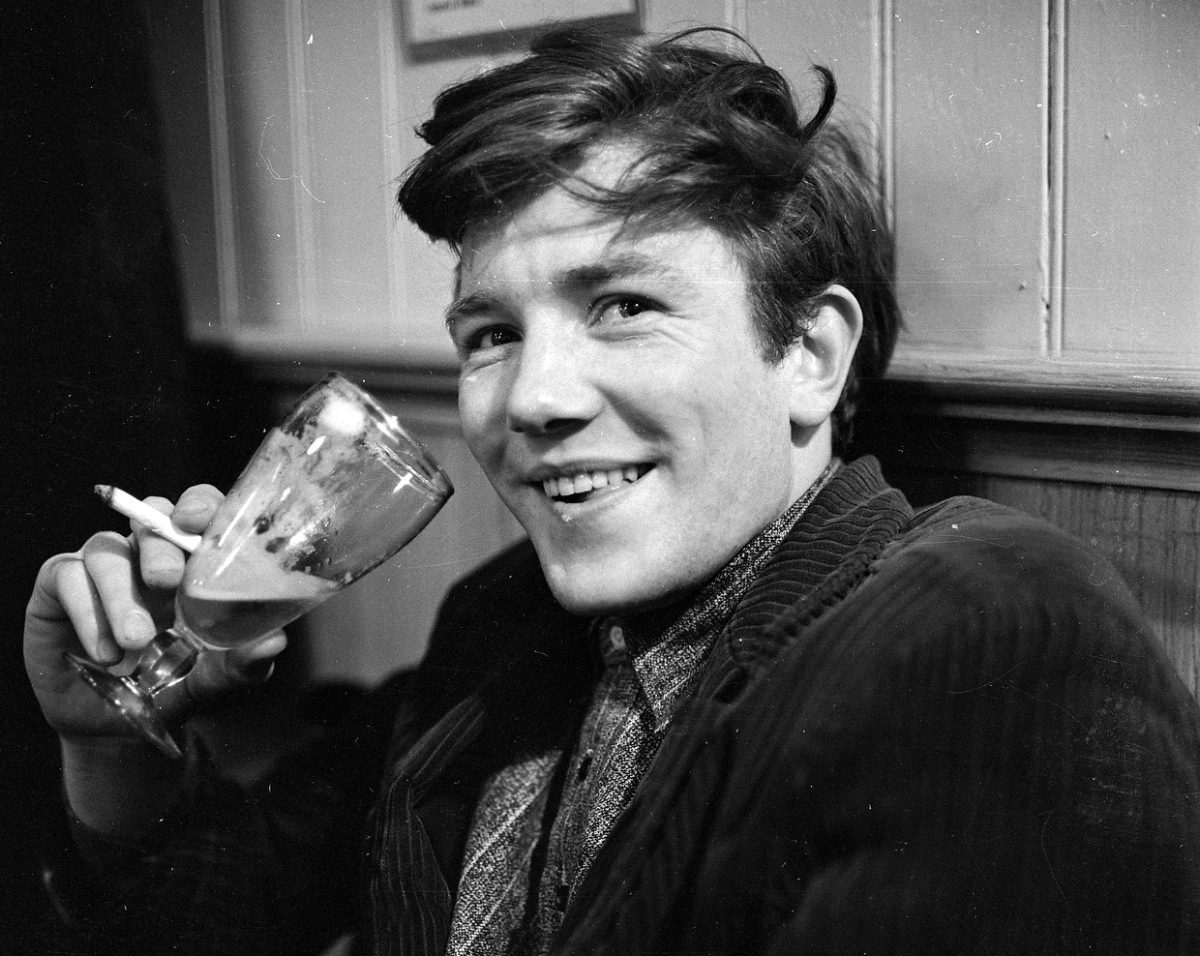

British film and stage actor Albert Finney enjoying a glass of beer in his regular pub behind the Cambridge Theatre in London in February 1961. (Photo by John Pratt/Keystone Features/Getty Images)

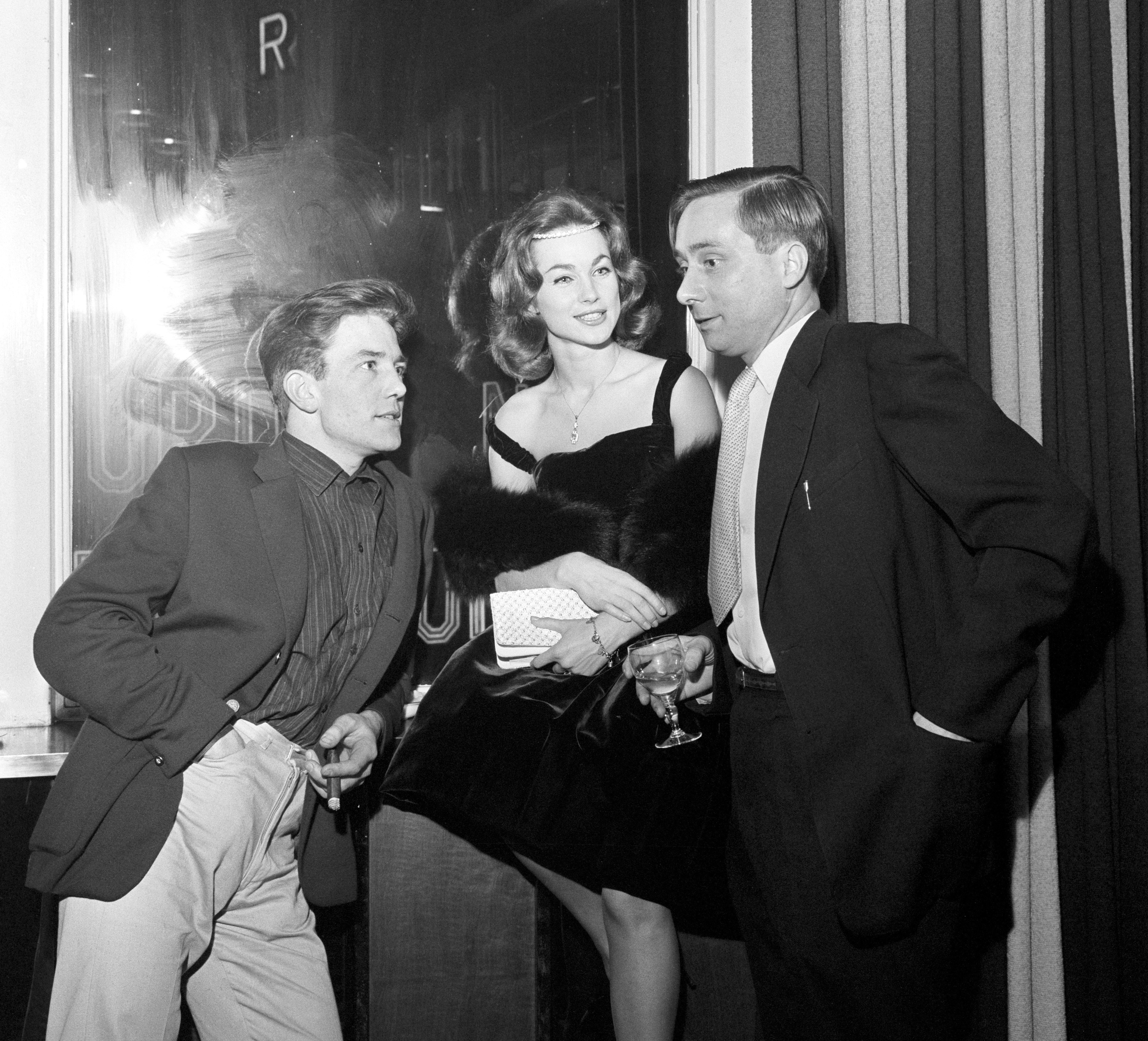

Albert Finney, Shirley Anne Field and Alan Sillitoe at the premiere for Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, October 1960.

A Taste of Honey

Shelagh Delaney, who was described by Jeanette Winterson as “the first working-class woman playwright”, said she was motivated to write A Taste of Honey after seeing Terrence Rattigan’s Variatons on a Theme at the Manchester Opera House. She came away thinking she could do better and that Rattigan’s work showed an “insensitivity in the way it portrayed homosexuals”.

In less than three weeks she wrote a play about a lively and determined Salford girl called Jo. After being left alone one Christmas she sleeps with a Nigerian sailor, gets pregnant and then carefully looked after by a gay textile design student. In fact a Taste of Honey is probably the first work to depict a gay working class man.

Although Delaney continued writing she never had a real hit again. The Guardian in 2011 called A Taste of Honey as “one of the defining plays of the 1950s working-class and feminist cultural movements.”

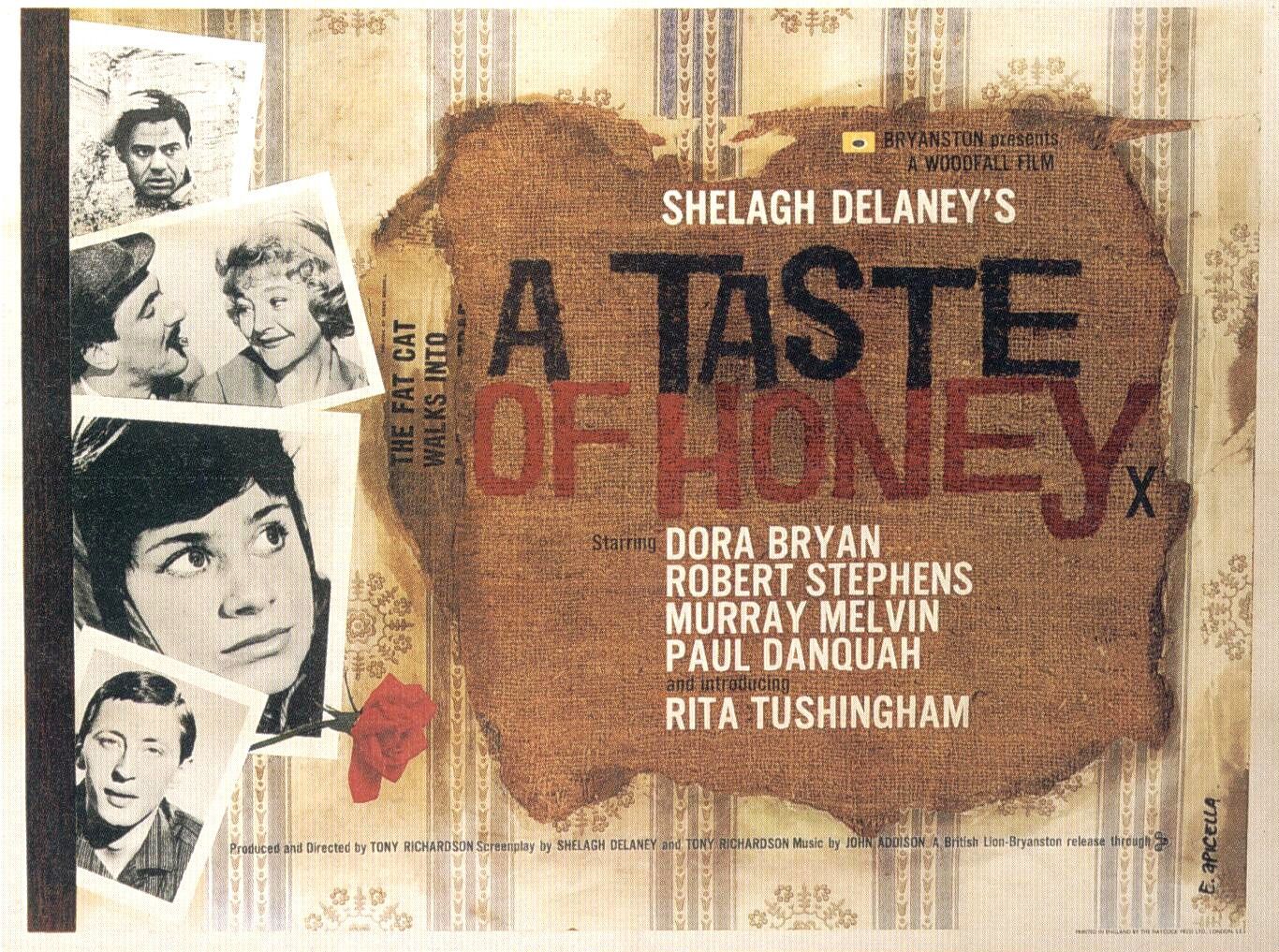

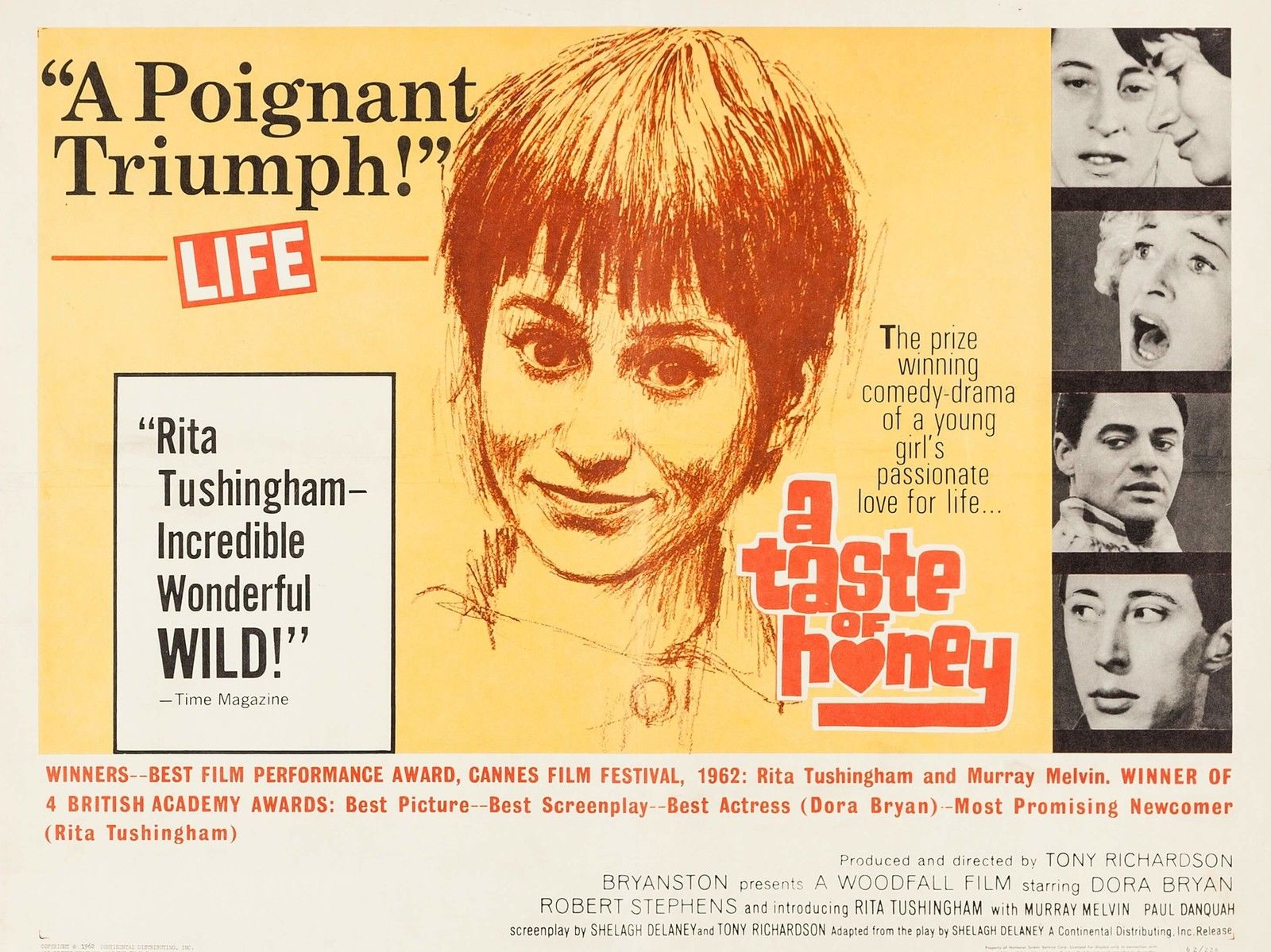

The film adaptation was written by Shelagh Delaney and the director Tony Richardson. Released in 1961 it won four BAFTAs including for the screenplay.

Shelagh Delaney’s A Taste of Honey West End Edition.

A Taste of Honey poster 1961.

Rita Tushingham

Paul Danquah & Rita Tushingham in ‘A Taste of Honey’ (1961), a screen debut for both

A Taste of Honey poster US

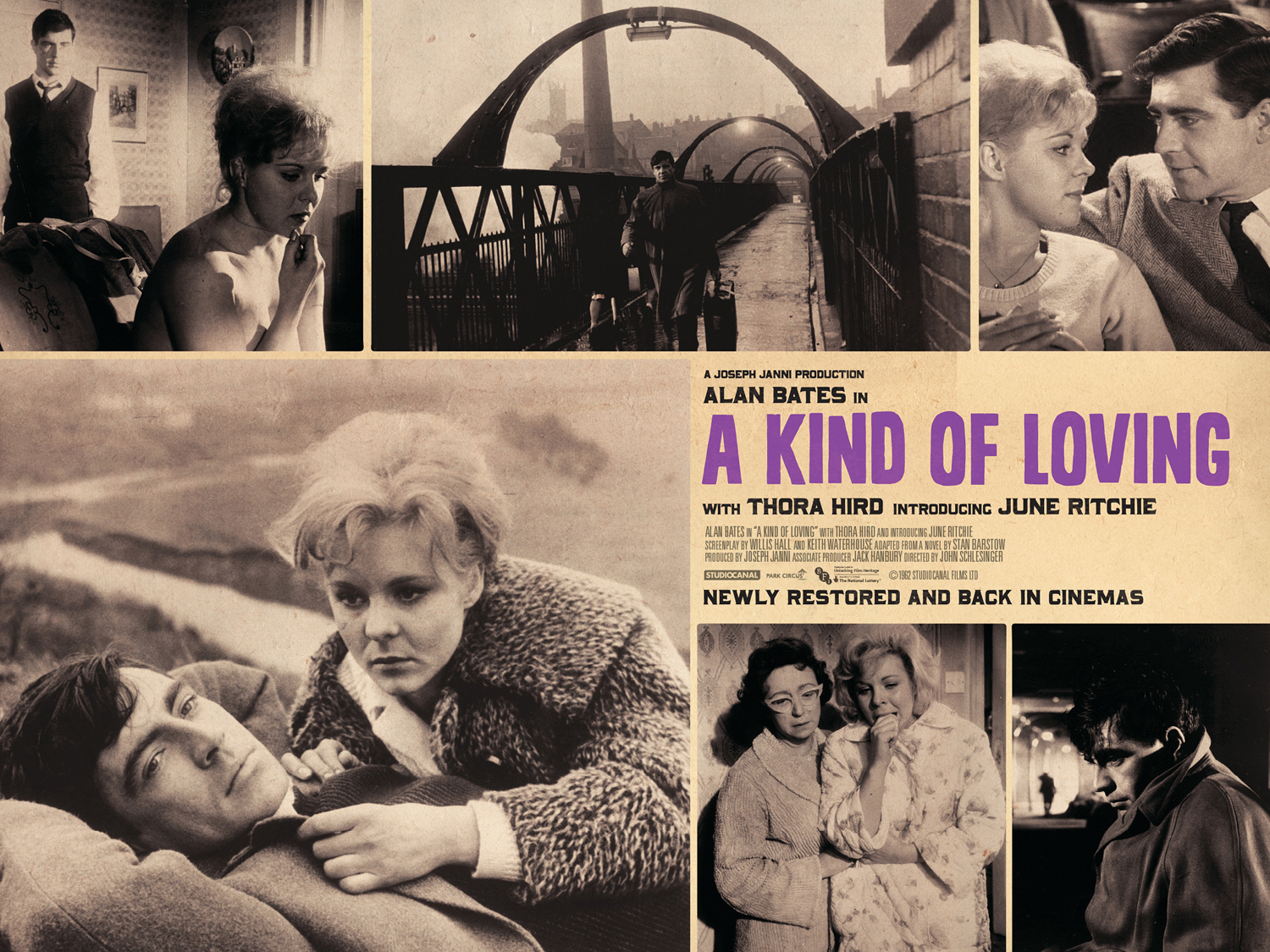

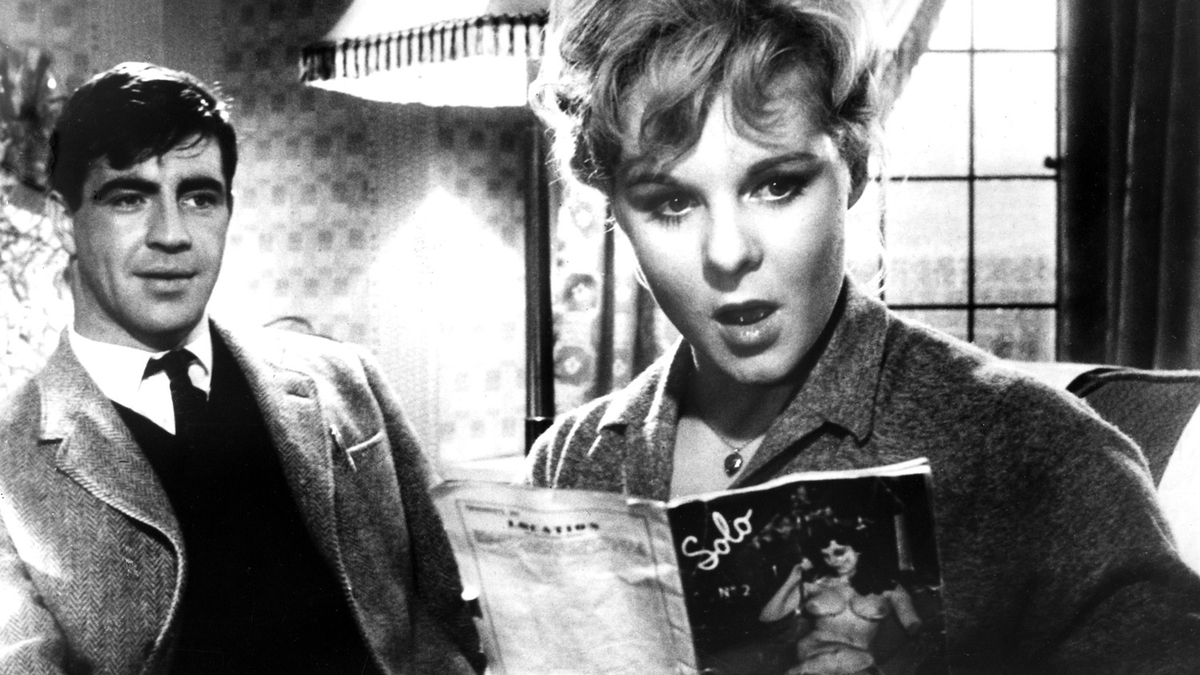

A Kind of Loving

A Kind of Loving first edition.

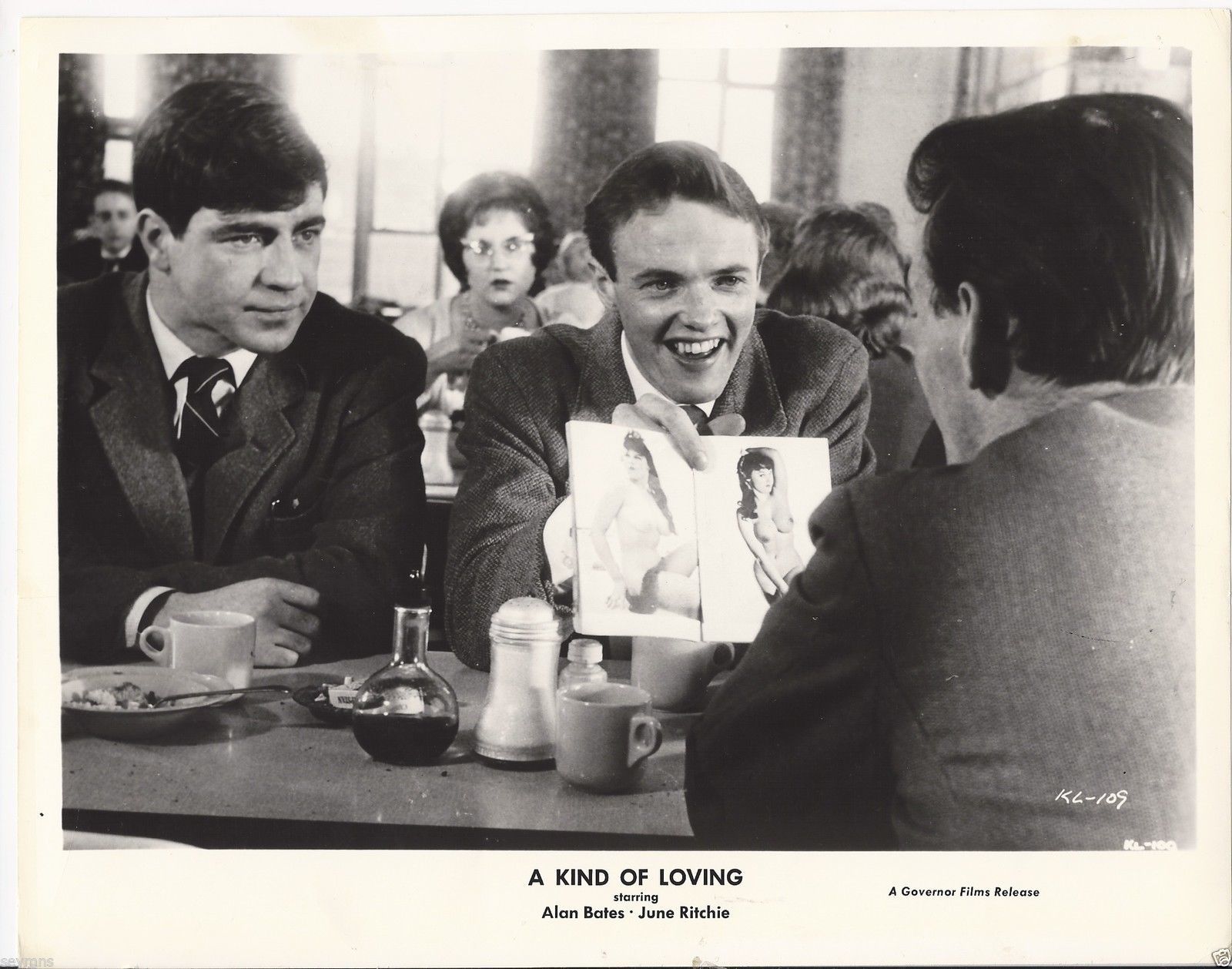

A Kind of Loving lobby card.

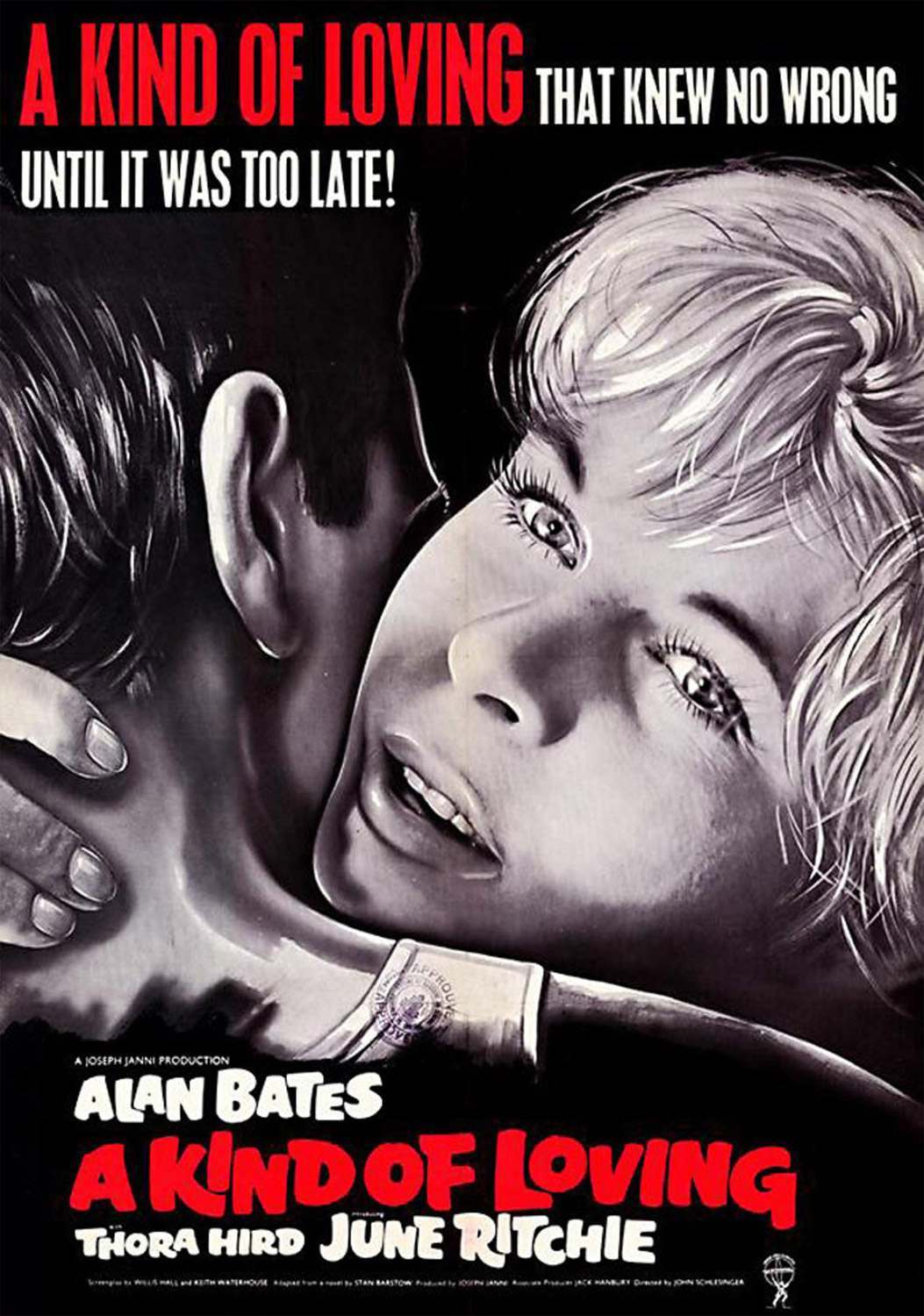

A Kind of Loving was released in 1962.

A Kind of Loving poster

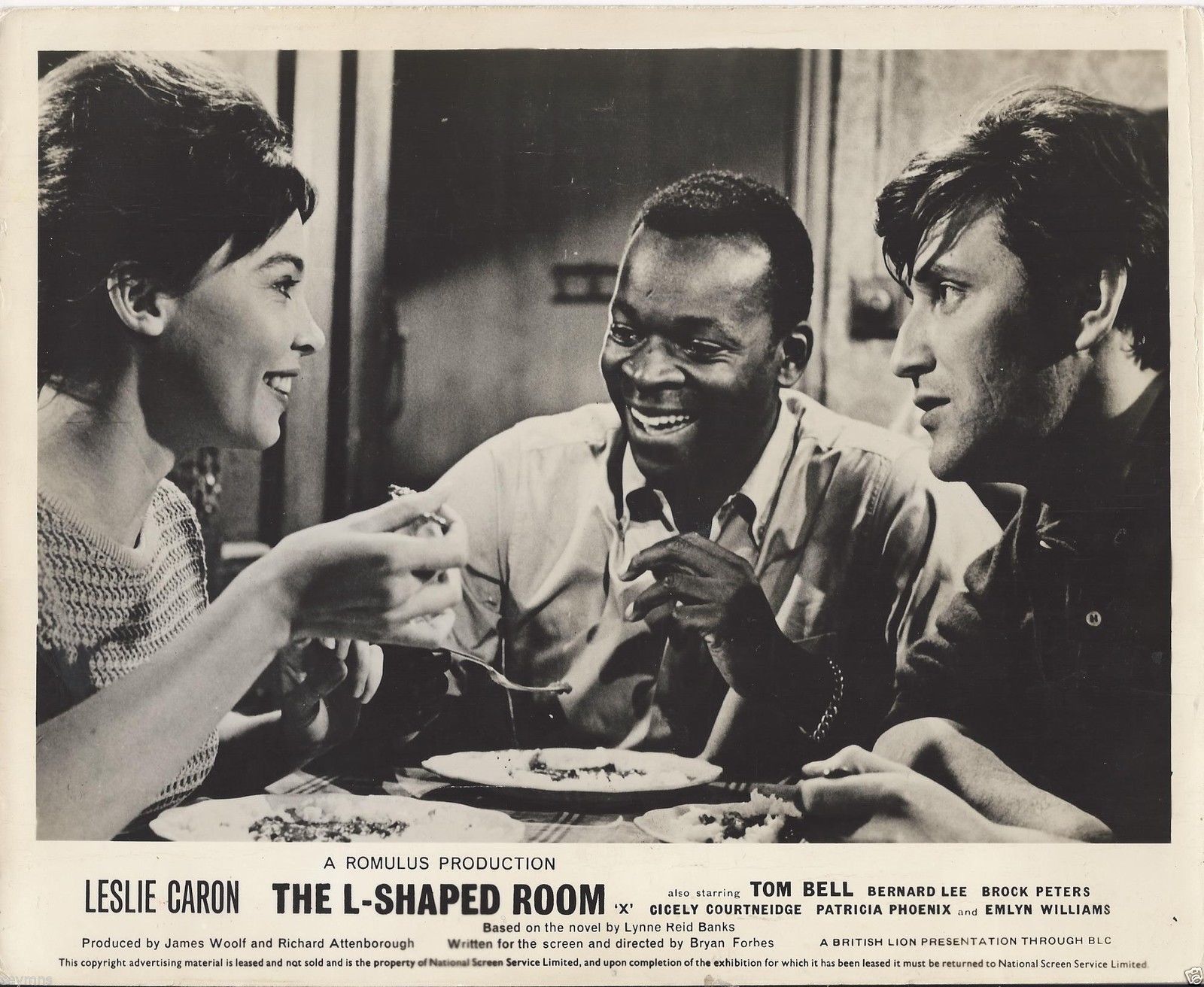

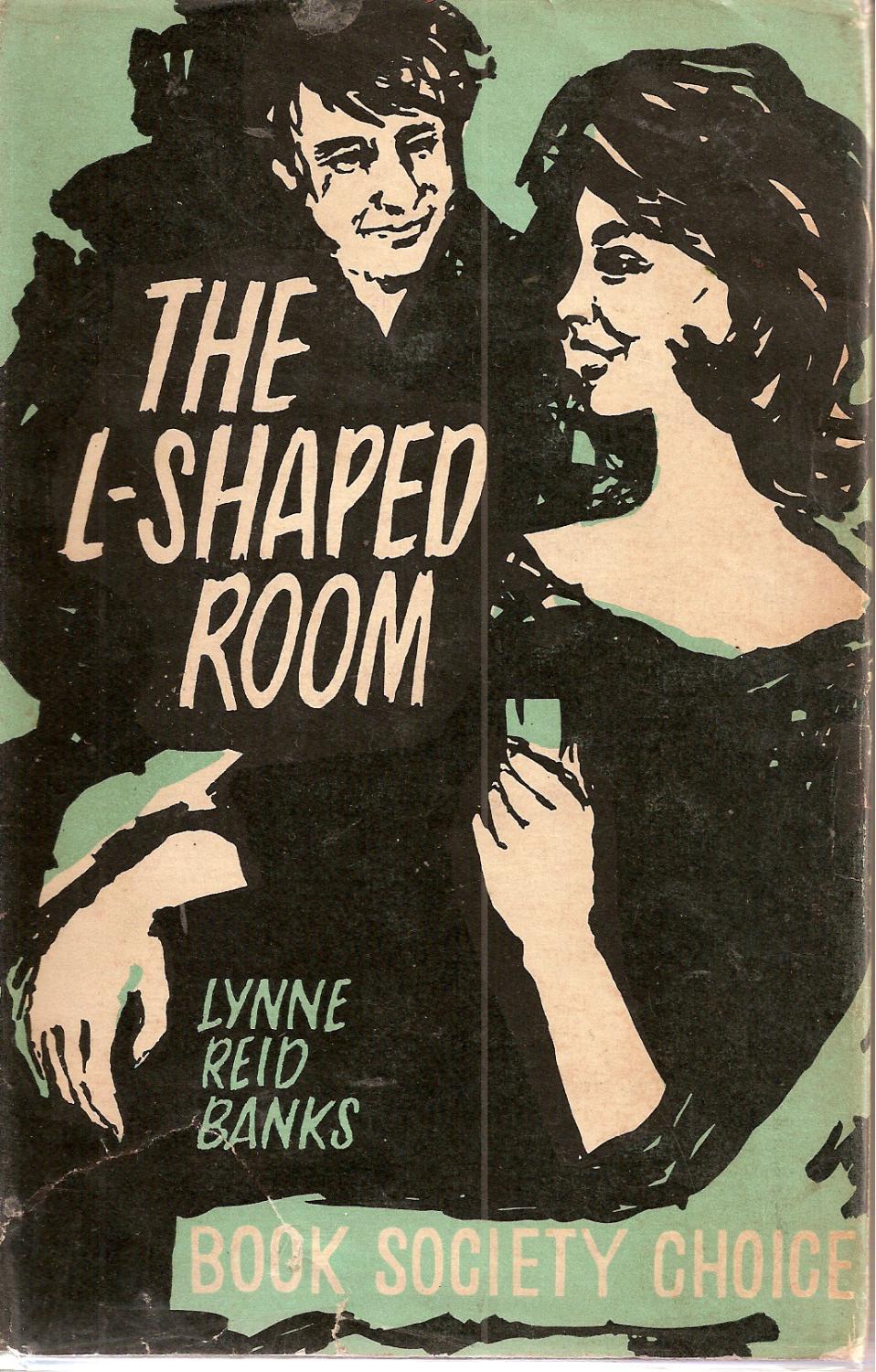

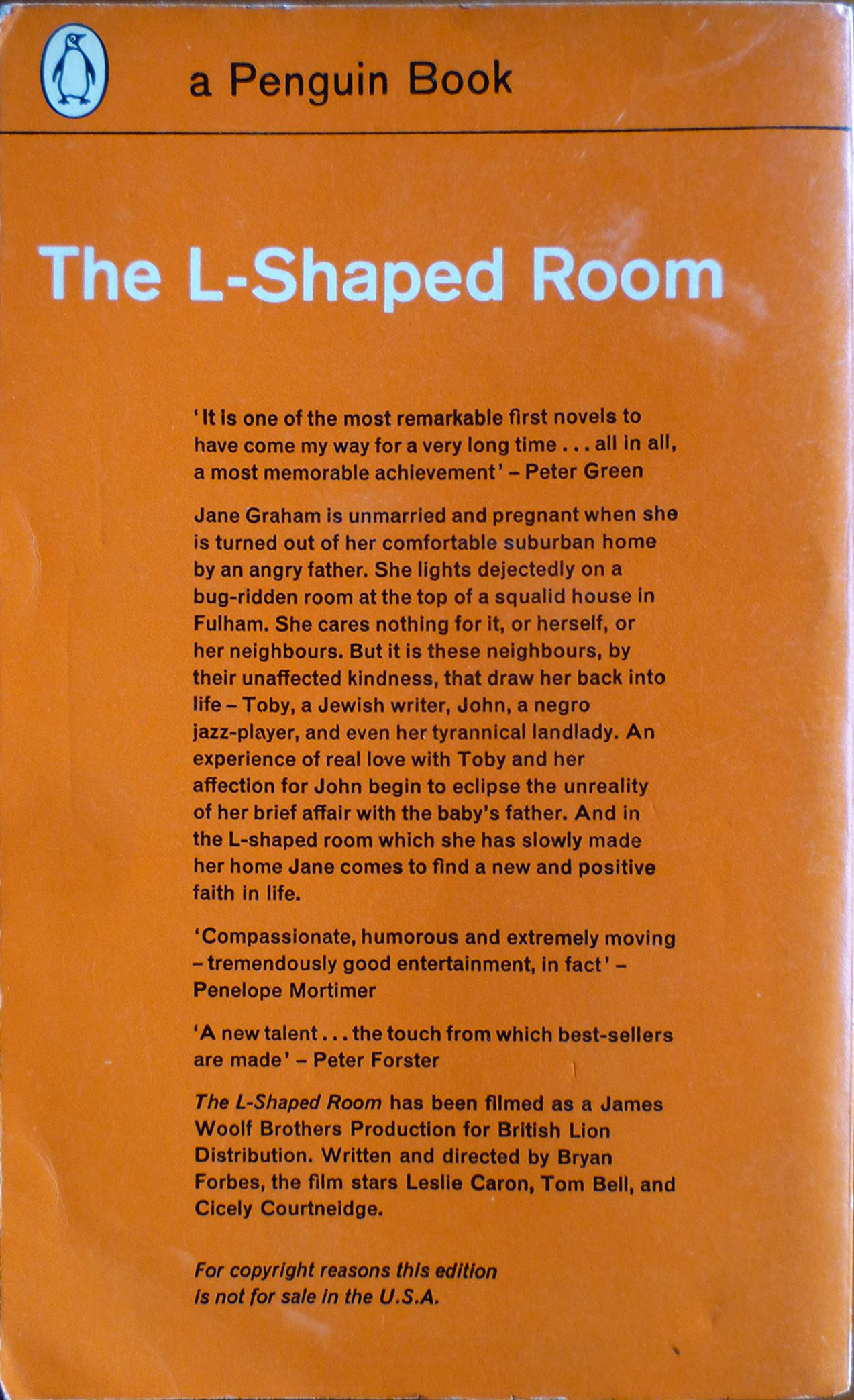

The L-Shaped Room

Jane Fosset: Oh, you English are so funny about smells. You hate garlic, you’re frightened of perfume unless it’s very cheap and very nasty, but you *love* the smell of fish and chips. First time I went out for a walk with an Englishman, he took us two miles out of our way so I could smell a fish and chips shop.

Toby: Oh, well, you see it’s a very powerful aphrodisiac for an Englishman. Before the war, most children were conceived on Friday nights.

Jane Fosset a 27 year old French woman, unmarried and pregnant, rents a room in a seedy London boarding house in a then run-down Notting Hill. The house is inhabited by an assortment of misfits. She considers getting an abortion, but is unhappy with this solution but starts a relationship with Toby, a struggling young writer who lives on the first floor. Eventually she comes to like her odd L-Shaped room of the title, and makes friends with all the eccentric and quirky people in the house. But she still faces two problems: what to do with her baby, and what to do with Toby.

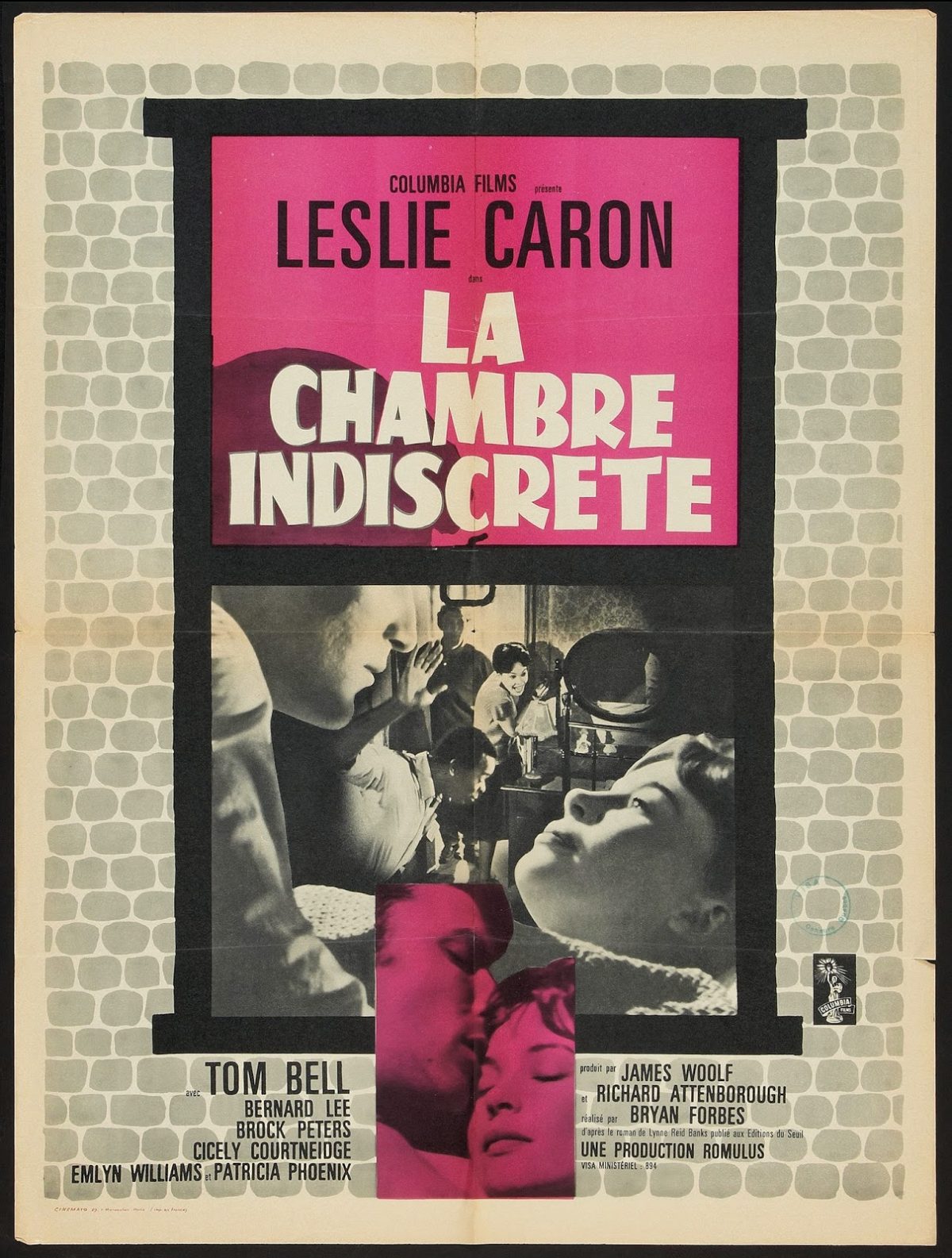

The L-Shaped Room was released in 1963 and directed by Bryan Forbes.

Lobby card for the L-Shaped Room.

Jane Fosset: You can’t afford it.

Toby: I know I can’t afford it. I can’t afford any of the bloody decencies of life. I can’t afford to take you out, I can’t afford to buy you a proper Christmas present, I can’t afford even to be able to tell you not to worry.

Toby: Look, I’m 28 years old, and I’m still living hand to mouth like a bloody tramp. I’ve been writing for ten years, I’ve written five stinking novels that nobody wants to wipe their behinds upon, and now you tell me I can’t even afford a bottle of non-vintage wine. Well, don’t tell me, because I don’t want to know! I just don’t want to know about it!

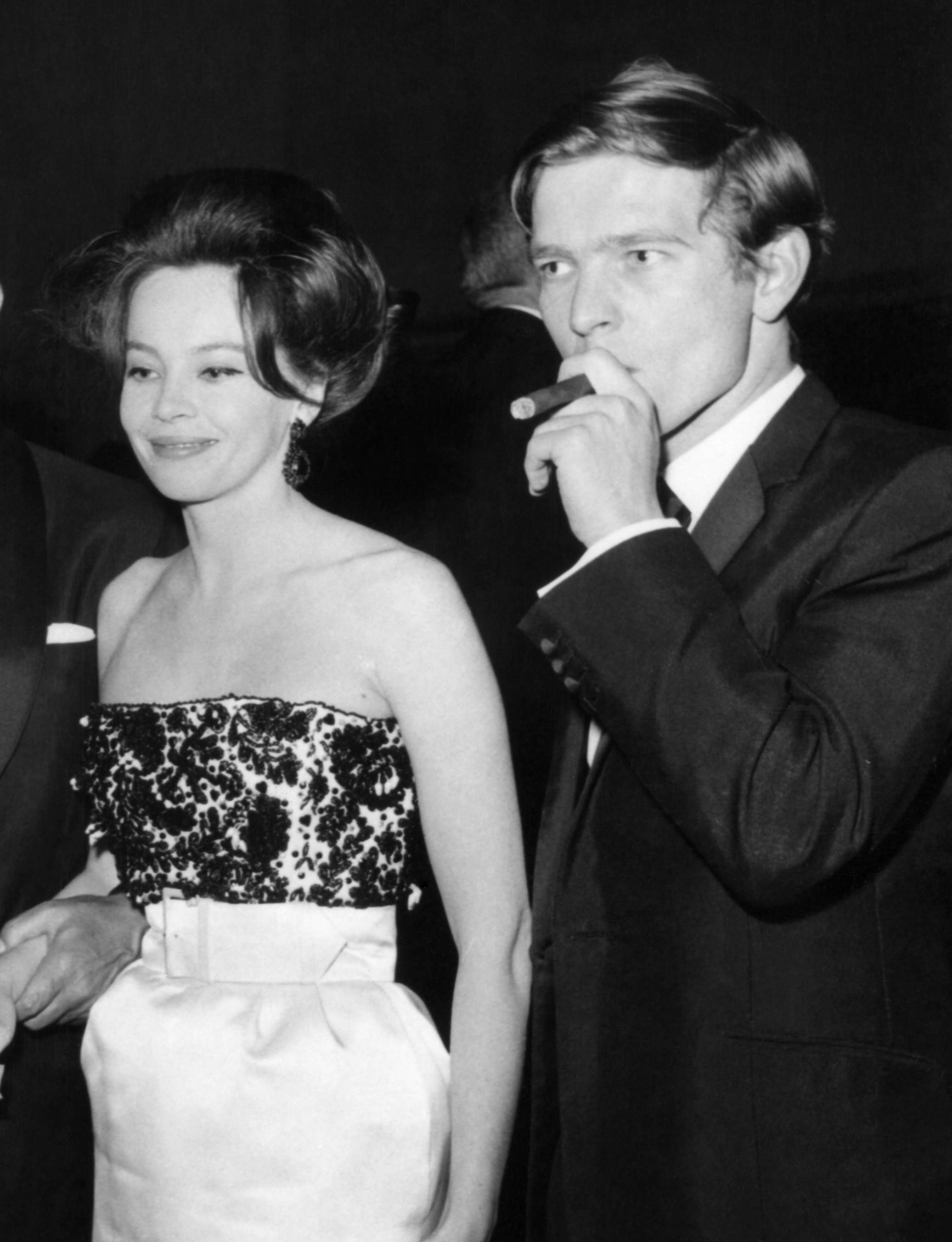

French actress Leslie Caron, Best Actress Award for “The L-Shaped Room” and English actor Tom Courtenay, most promising newcomer for his role in “The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner” at the British Film Academy Awards Dinner at London’s Hilton Hotel. May 1963.

L-Shaped Room first edition

Leslie Caron in the L-Shaped Room

The L-Shaped Room

LA CHAMBRE INDISCRETE – French Poster

Leslie Caron

The L-Shaped Room lobby card

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.