“Yesterday, December 7, 1941 – a date which will live in infamy – the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan”

– President Franklin D. Roosevelt in his address to a joint session of Congress.

“I was truly depressed on December 7th when I heard the news on the radio. I was a student at Berkeley, University of California Berkeley, at the time in my junior year. And I thought, Oh, this is it. It’s — I could see nothing but bad things happening for me in the future.”

– Warren Michio Tsuneishi, born to Japanese immigrant parents on July 4, 1921, in Monrovia, California.

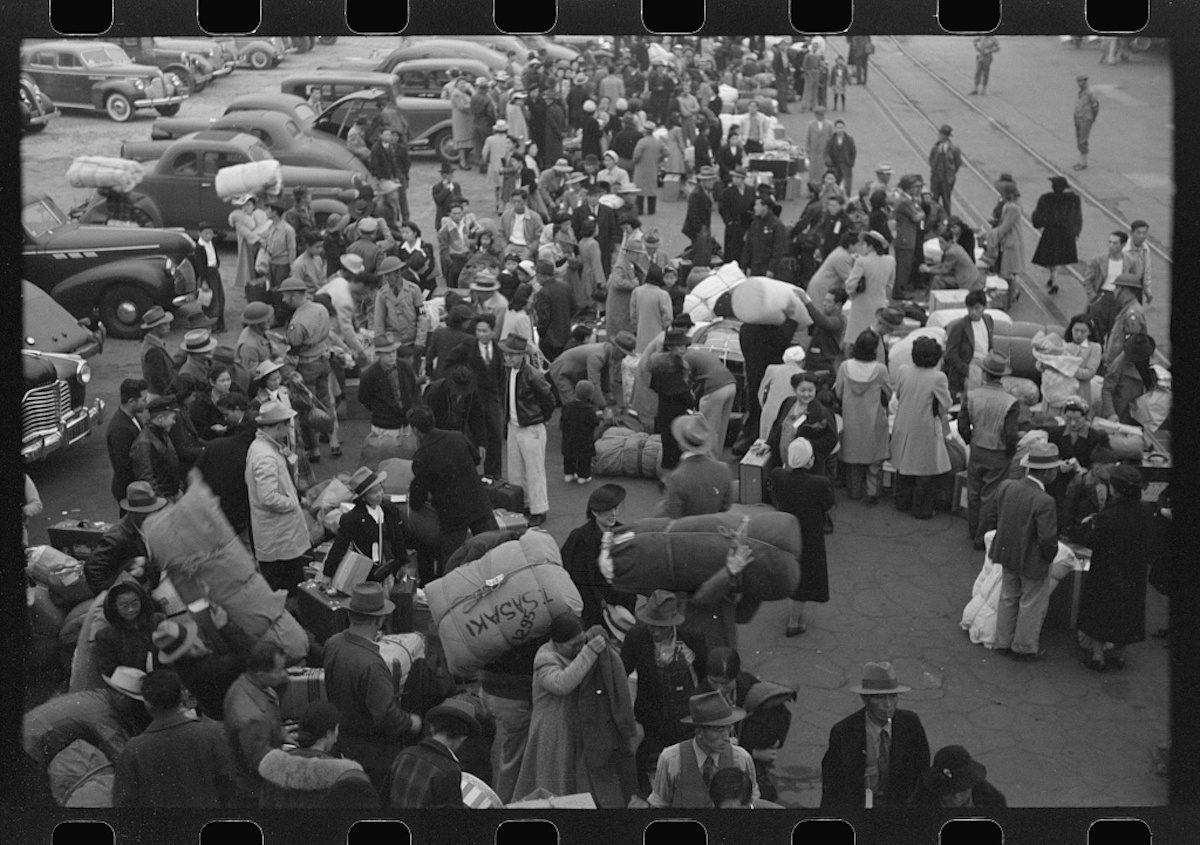

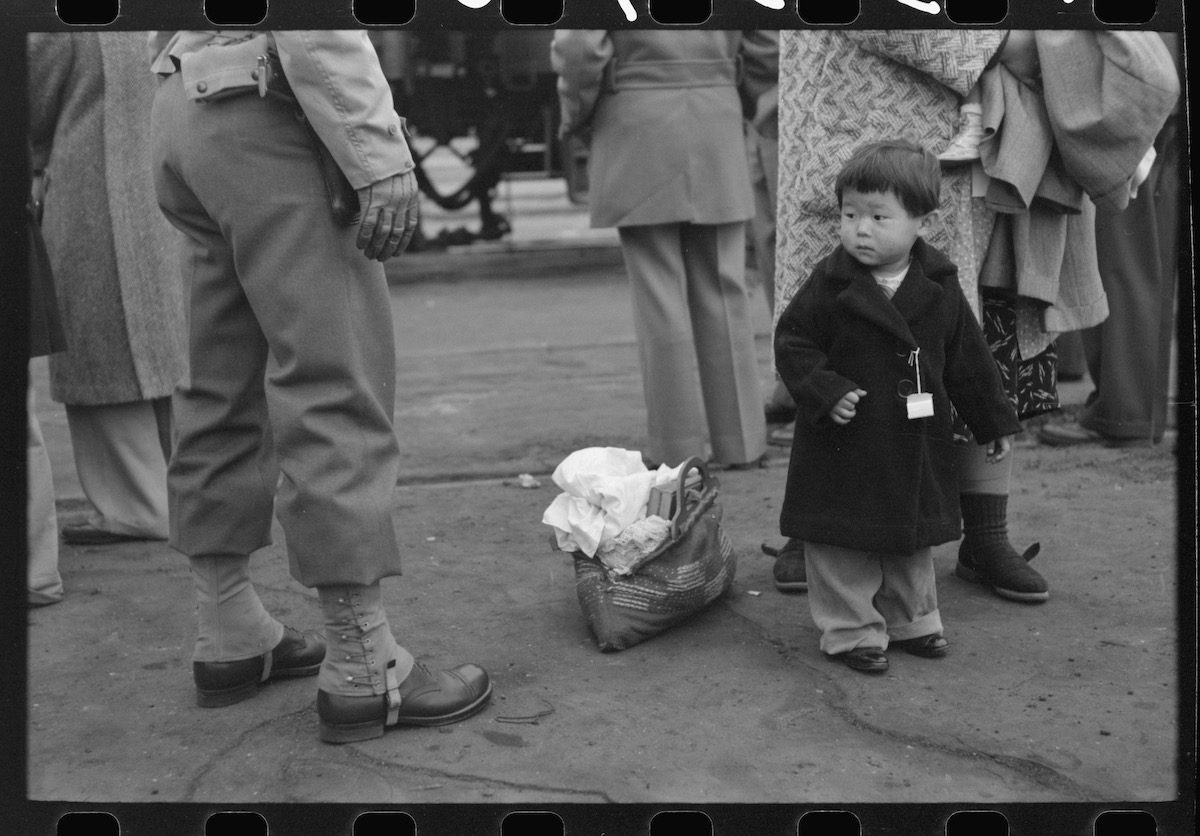

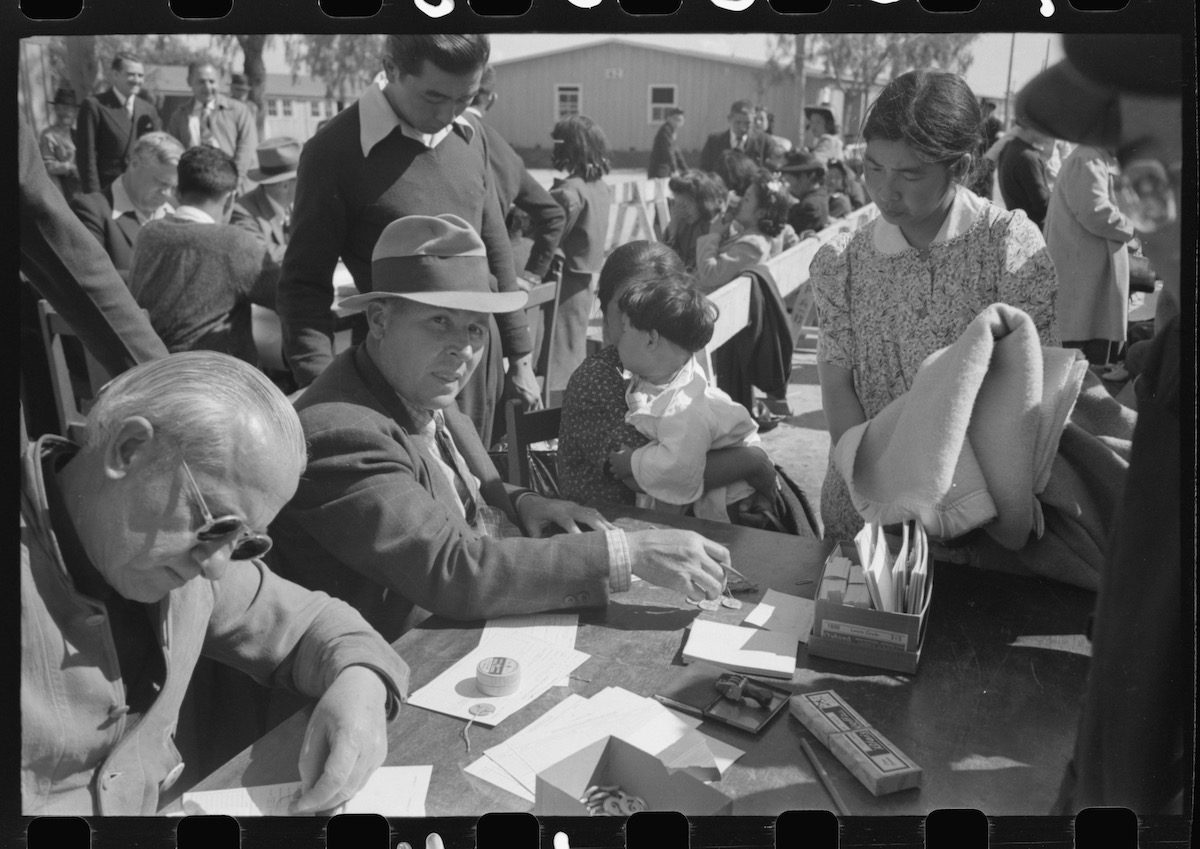

Santa Anita reception center, Los Angeles County, California by Russell Lee, 1942 Apr.

The repercussions of Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor were immediate. Along the US West Coast, prominent Japanese Americans were arrested. Japanese Americans were forced from their jobs. They were subjected to verbal and physical attacks. All achievement was taken from them.

And then it got worse. President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19 1942, authorising the evacuation and relocation of “any and all persons” from “military areas”. Soon after, California and much of Washington and Oregon were deemed military areas. The evacuees were suspected, without evidence, of being potential supporters of Japan, with which the US was at war. General DeWitt, general of the western defence command in Presidio, San Francisco, issued a military proclamation for a curfew for all Japanese Americans living in the West Coast states. And then the process of relocating tens of thousands of Japanese Americans to prison camps began.

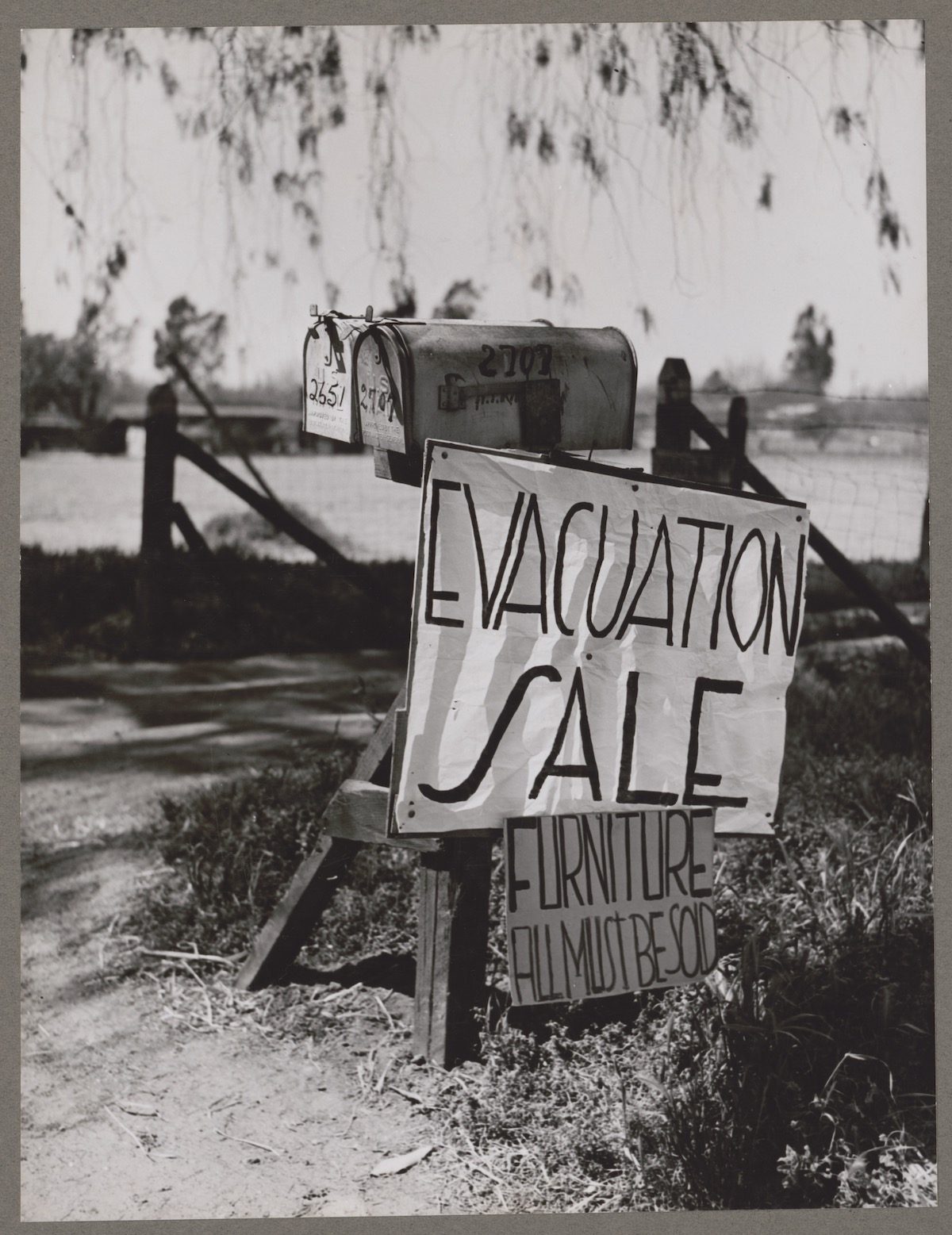

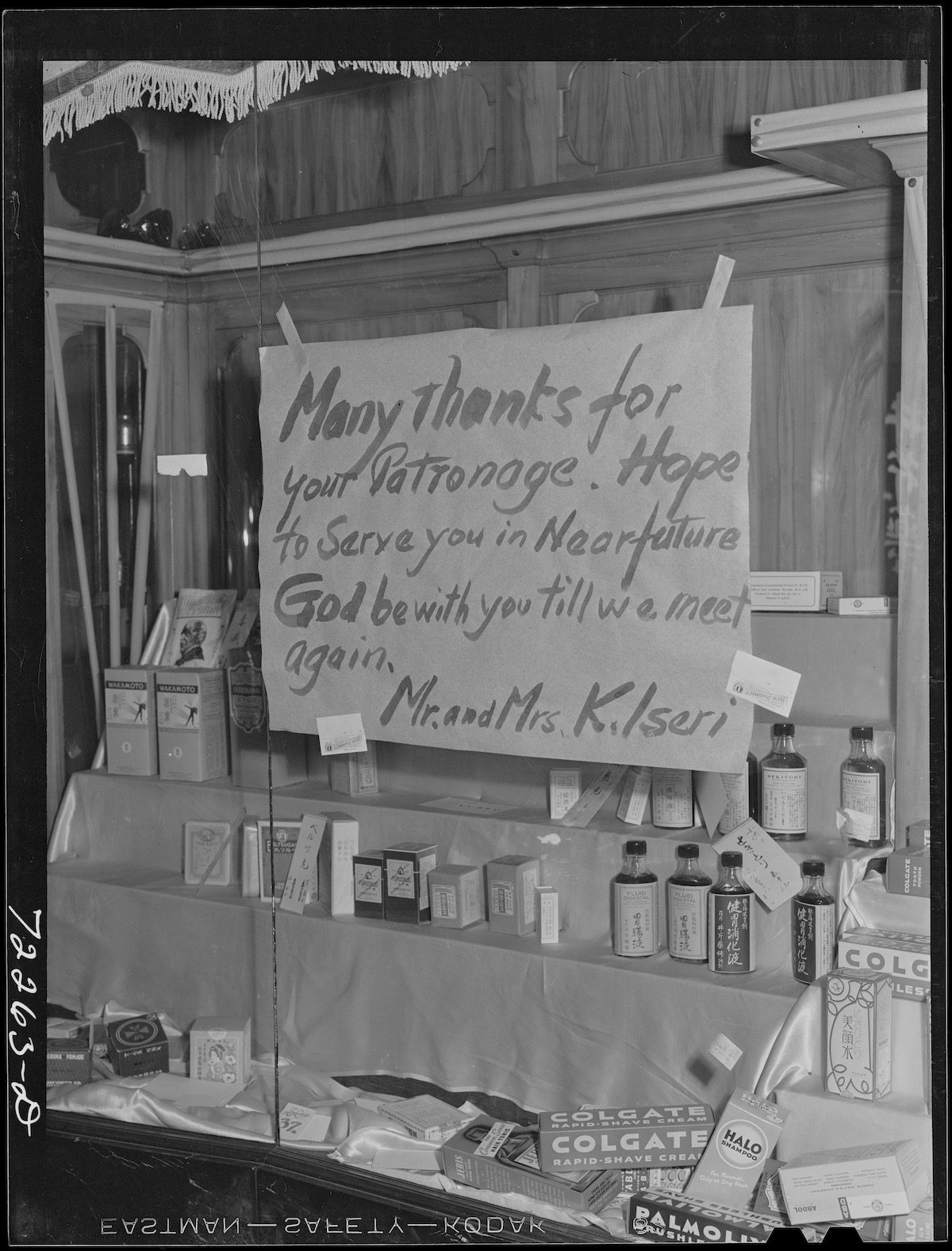

The evacuation of Japanese-Americans from West Coast areas under U.S. Army war emergency order Japanese try to sell their belongings. Russell Lee, Los Angeles, Calif., Apr. 1942.

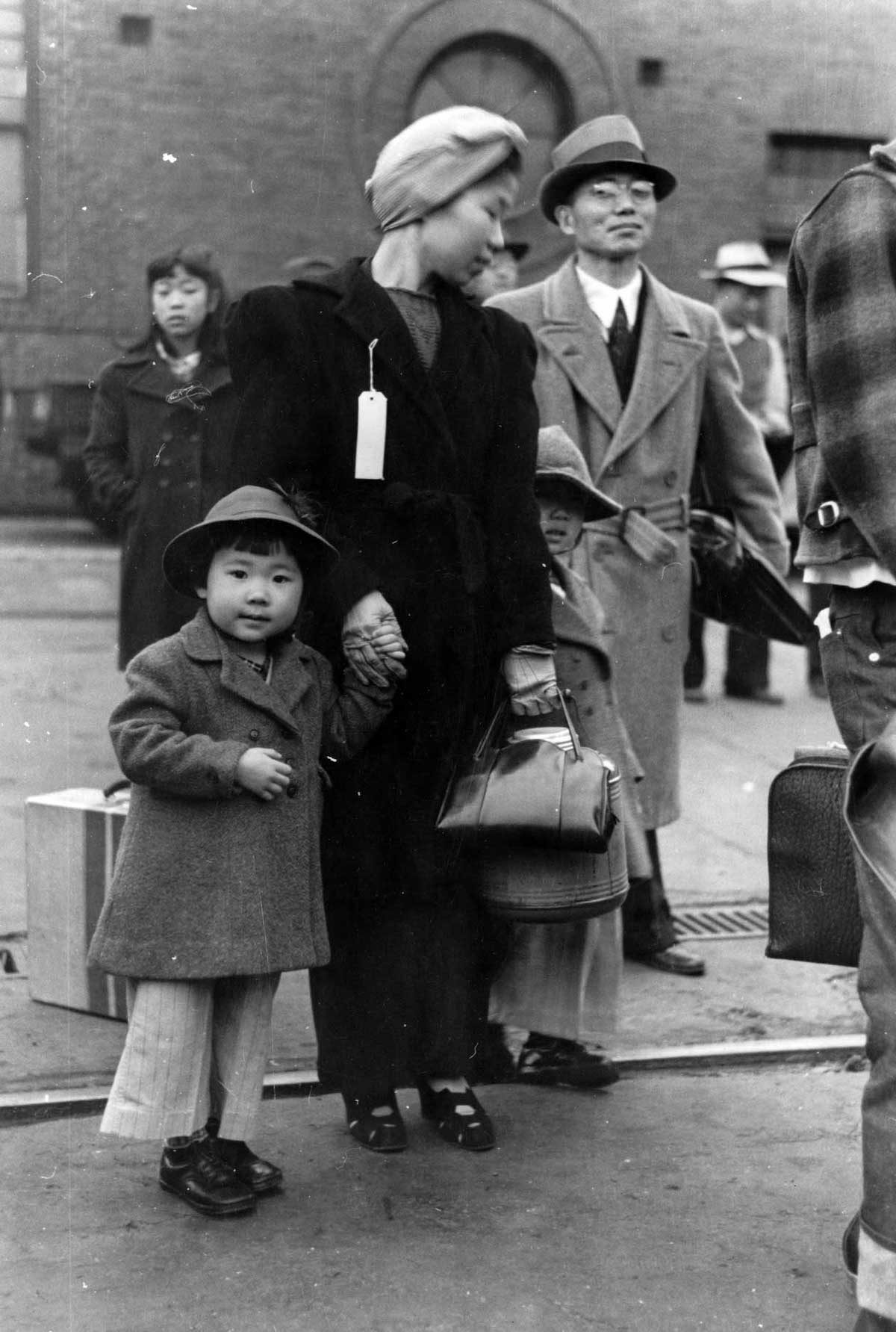

Japanese Americans were ordered to register, handed identification numbers, inoculated against communicable diseases and given just days to sell any assets. Homes, farms, crops, businesses were abandoned. Anything these Americans now deemed to be enemies of the State, criminals in waiting, could not carry with them to the camps were sold.

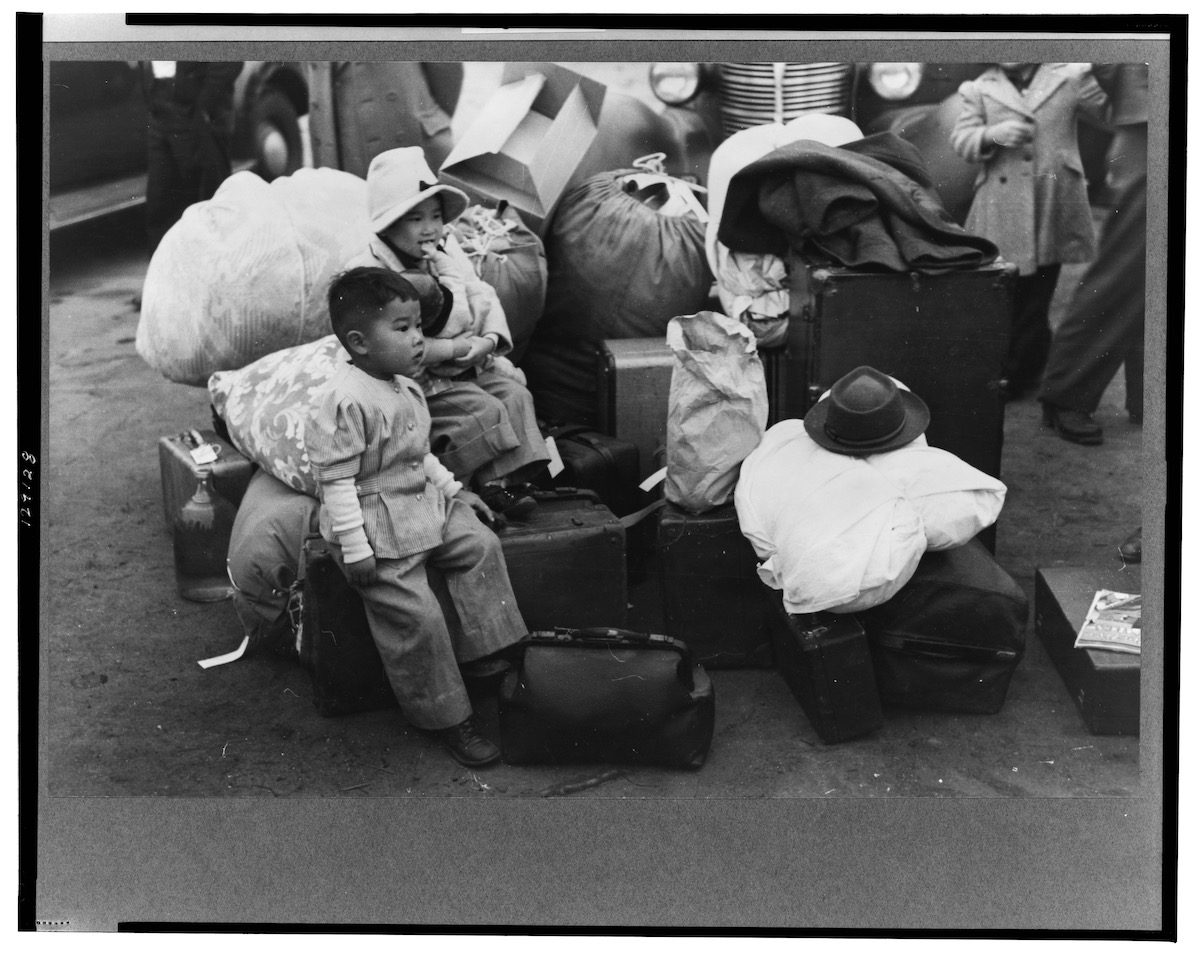

Ordered to gather at large places, like racetracks and fairgrounds, around 120,000 Japanese-Americans were housed in temporary accommodation, including tents and stables. There they waited to be despatched to their assigned war relocation camps in remote, desolate, arid and inhospitable areas.

The camps were surrounded by barbed wire. Armed guards looked down from watchtowers. Families lived in one room.

The prisoners made life as normal as they could, setting up schools, community centres, producing newspapers and stocking up on goods form the outside world on weekly supervised trips to nearby towns, like Nyssa, Oregon. If they needed various clothing and supplies at the time, they could order through the mail-order catalog, especially the Sears Roebuck catalog. They could send letters and use the communal pay phones. But they could never be free.

Los Angeles, California. The evacuation of Japanese-Americans from West Coast areas under U.S. Army war emergency order. Japanese-Americans watching train taking their friends and relatives to Owens Valley. By Russell Lee – 1942 Apr.

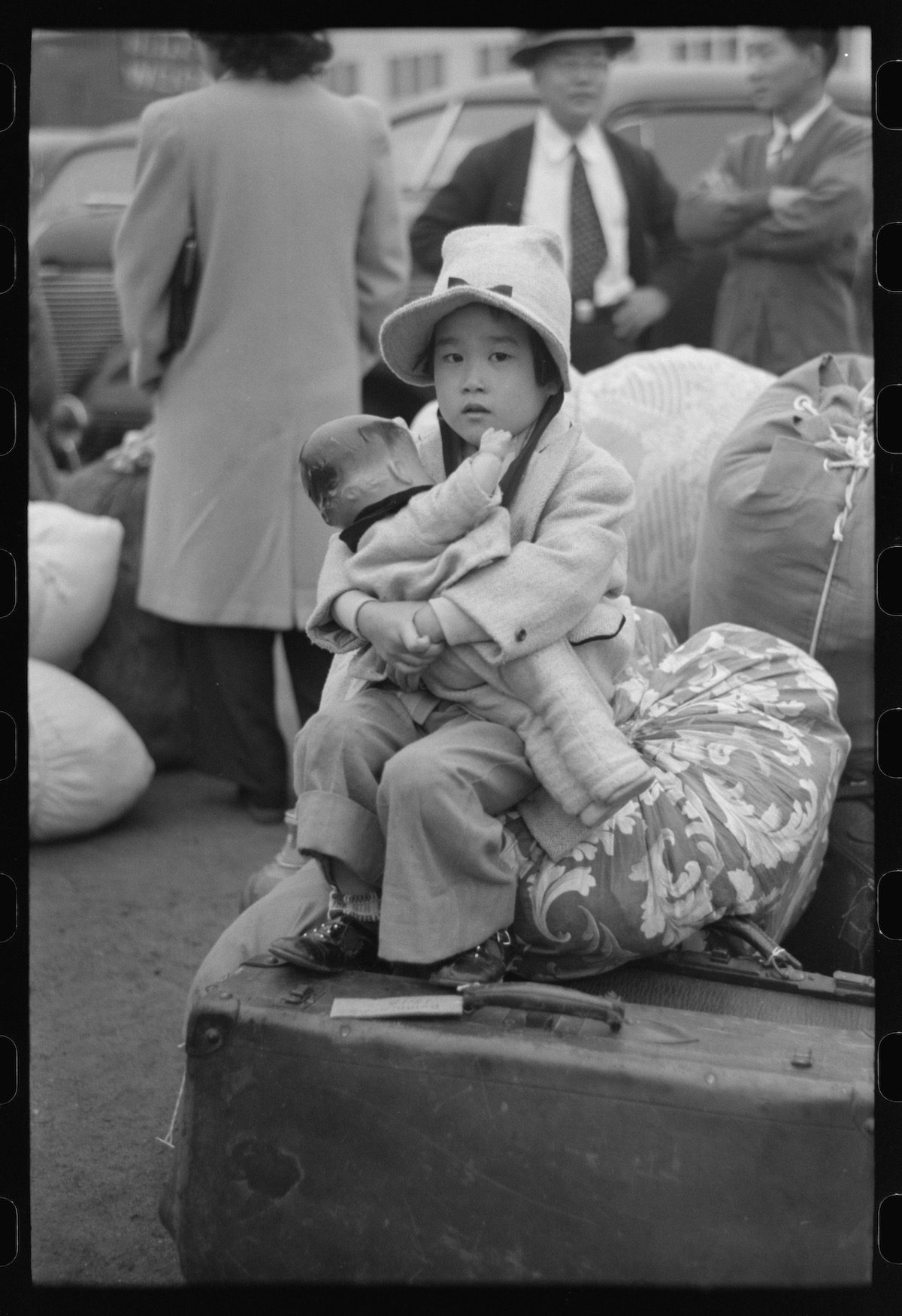

Hayward, California, Two Children of the Mochida Family who, with Their Parents, Are Awaiting Evacuation – by Dorothea Lange

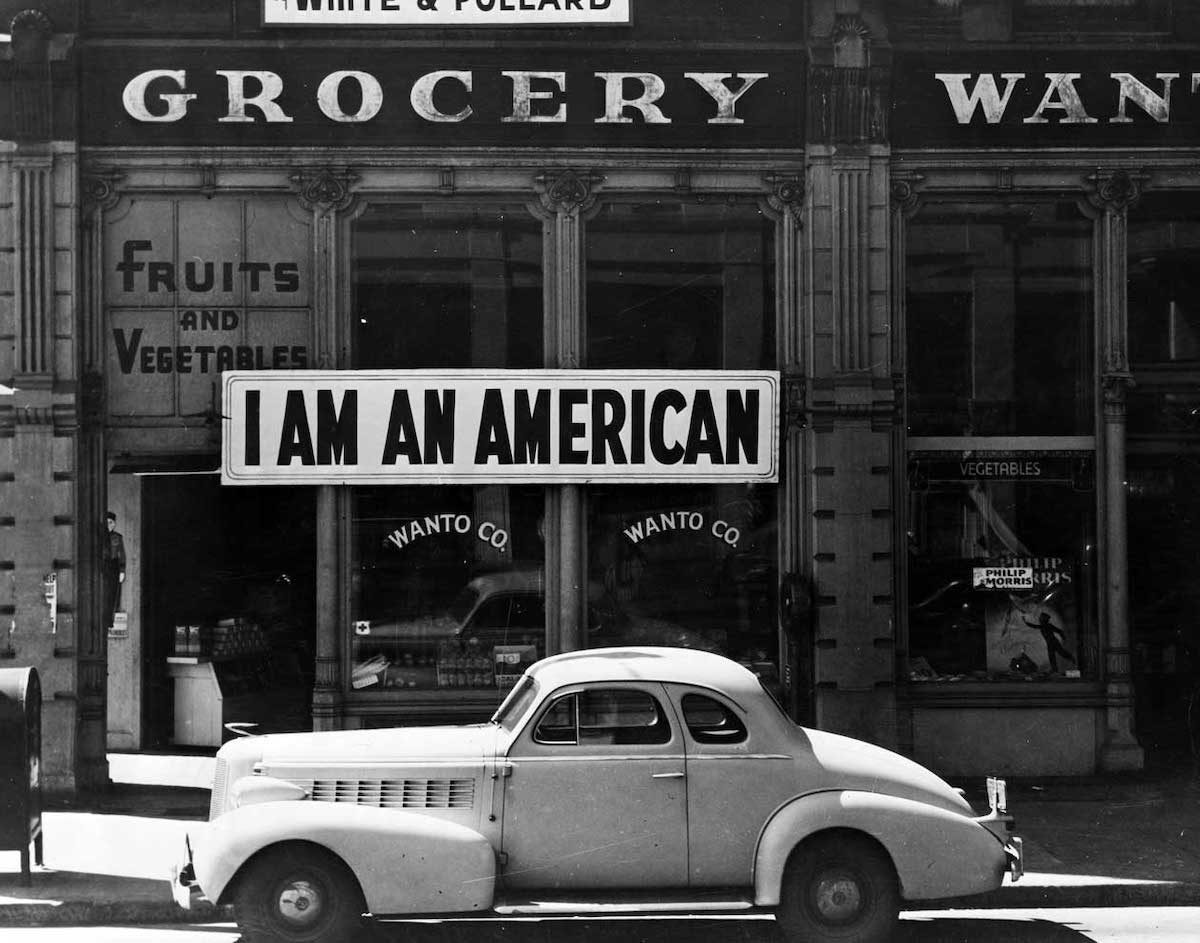

Oakland, Calif., Mar. 1942 by Dorothea Lange. A large sign reading “I am an American” placed in the window of a store, at [401 – 403 Eighth] and Franklin streets, on December 8, the day after Pearl Harbor. The store was closed following orders to persons of Japanese descent to evacuate from certain West Coast areas. The owner, a University of California graduate, will be housed with hundreds of evacuees in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration of the war

After Japanese forces bombed Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entered World War II, his family was evacuated to Heart Mountain, a Japanese internment facility in Wyoming. But Tsuneishi craved freedom and the chance to serve his country, in spite of his family’s confinement. He volunteered for the Military Intelligence Service Language School and served in the Pacific, translating captured documents that gave U.S. forces a big advantage in securing the Philippines and Okinawa.

More than 30,000 Japanese American men enlisted in the armed forces. The all Japanese American 442nd Regiment became the most decorated unit of its size in U.S. history.

My parents were immigrants from Japan coming to this country in the first decade of the 20th century, 1907, 19 — thereabouts. My father went through — put himself through high school, Monrovia High School, and wanted to enter — entered U.S.C. and wanted to study for the ministry. But, you know, health forced him out of that, returns to Japan, met my mother and they decided to get married. He came back alone, but she was a schoolteacher and had to stay there for a mandatory period of service. He set — he came off the farm in Japan, set himself up as a truck farmer growing strawberries and other berries in southern California. That’s — and I grew up on a truck farm.

…

The Army had said we were under — the evacuation was set up by the U.S. Army. The Army set up temporary assembly centers, and my parents — my family lived in Southern California near the Santa Anita racetrack. The racetrack was turned into a assembly center. The Pomona fairgrounds about 20 miles east of us was set up as an assembly center. And there were — the evacuation itself began in May. They stayed in these temporary assembly centers for a few months, and then they were shipped to permanent — ten permanent relocation centers in the interior states of the United States.

…we were permitted to carry — whatever we could carry we could take with us. Some families lost — for some people, it was a very expensive process. A friend of mine had a very thriving grocery store, and he lost that completely. He and his family lost that completely. My father lost the berries that were growing and coming to bear at the time. It was an economic catastrophe for most of the families.

The funny thing was seven years ago I was a guest of the German government to visit libraries, and we wound up in Munich. And we had a half day off. And another fella and I, a member of this team that was invited, asked if we could visit the Dachau memorial. I just wanted to check out a German concentration camp and see what it — how it compared. And physically they were remarkably similar, that is to say, Heart Mountain War Relocation Center and the Dachau — except, of course, the spirit was entirely different. Dachau was a death camp. American relocation centers are much, much more friendly to those of us who were interned there.

…

My older sister who had gotten a — Florence who had gotten a teacher’s training at the University of California Los Angeles in 1939 had been unable to get a job as a teacher, but once she got into a relocation center she was hired as a teacher at the sum of $17 a month or something of that sort. But it was a professional position. Others, my father, the first generation — the parents were for the most part I had thought for the first time in their lives because they had worked like mad to make a living mostly they were farmers or gardeners or small shopkeepers. My father somehow had managed to bring along — I said earlier that you could take in only what you could carry. How he managed it I don’t know. But he had a collection of books, especially books on poetry, Japanese poetry. And he made those available to other members of the Heart Mountain community, and he was even permitted to go outside to the other relocation centers to collect books from other people in those camps. This was not — as I said, the relocation centers were not death camps. They were not that highly restrictive. Your liberty was taken away from you; but there are ways to get around, move around, communicate with the outside, get out if you had a good reason to.

…

Photograph shows Shizuko Ina standing behind unidentified Japanese Americans at Kinmon Hall, San Francisco, on April 25, 1942, waiting for an appointment to be assigned “family number” 14911 before being removed from her home and incarcerated with her husband, Itaru Ina (1914-1977), in a detention facility at Tanforan Racetrack on April 30, 1942. She was later moved with her husband to a camp in Topaz, Utah, and then to Tule Lake Segregation Center, near Newell in Northern California. The family was separated in July 1945 when Itaru was transferred to Fort Lincoln, a Department of Justice camp for “enemy aliens” in Bismarck, North Dakota, and reunited in April 1946 at Crystal City Internment Camp in Texas. (Source: Satsuki Ina, daughter of Shizuko Ina, February 2020 – 25 April 1942]

You know, what a lot of Americans don’t understand is that the schools do a very good job of Americanizing you, pledge allegiance to the flag. I pledged allegiance without the under God which later has become an issue recently. But the songs we sang, “America the Beautiful”, history lessons we went through, the civics lessons, we became thoroughly Americanized in the process. And so when Japan struck Pearl Harbor, that’s what I meant when I said earlier I could see only nothing but bad things happening to us because while on the one hand we thought of ourselves as Americans and my own self-image was that of — since I was born on the 4th of July as a Yankee Doodle Dandy, I’m a Yankee Doodle Dandy born on the 4th of July [singing], you know. But if you look at me, you know right away that I’m not a very good stereotype Yankee Doodle — maybe Squanto but not Yankee Doodle. But in my heart, I always thought of myself as an American. But there was enough of a Japanese cultural influence in my makeup, my own emotional makeup, that I instead of — instead of resisting the unconstitutional acts that the government had taken against me I took — I took it without fighting. To that extent, I guess I was more Japanese than I was American if that stereotype is true that Americans are individuals who fight for the rights if they are trampled upon and so forth. Well, there are a lot of Americans who are not that way either. But — well, what else can I say?

Los Angeles, California. Japanese-American child who is being evacuated with his parents to Owens Valley- Russell Lee 1942

Japanese-American child who will go with his parents to Owens Valley by Russell Lee – 1942 Apr.

Never lose hope, always believe in your country and fight for your country when it needs to have either soldiers or civilians fighting for the Constitution of the United States.

Waving good-bye to friends and relatives who are leaving for Owens Valley

Japanese-American child who is being evacuated with his parents to Owens Valley by Russell Lee

Japanese-Americans waiting for a train to take them and their parents to Owens Valley by Russell Lee, 1942 Apr.

Santa Anita reception center, Los Angeles, California. The evacuation of Japanese and Japanese-Americans from West Coast areas under U.S. Army war emergency order – Russell Lee

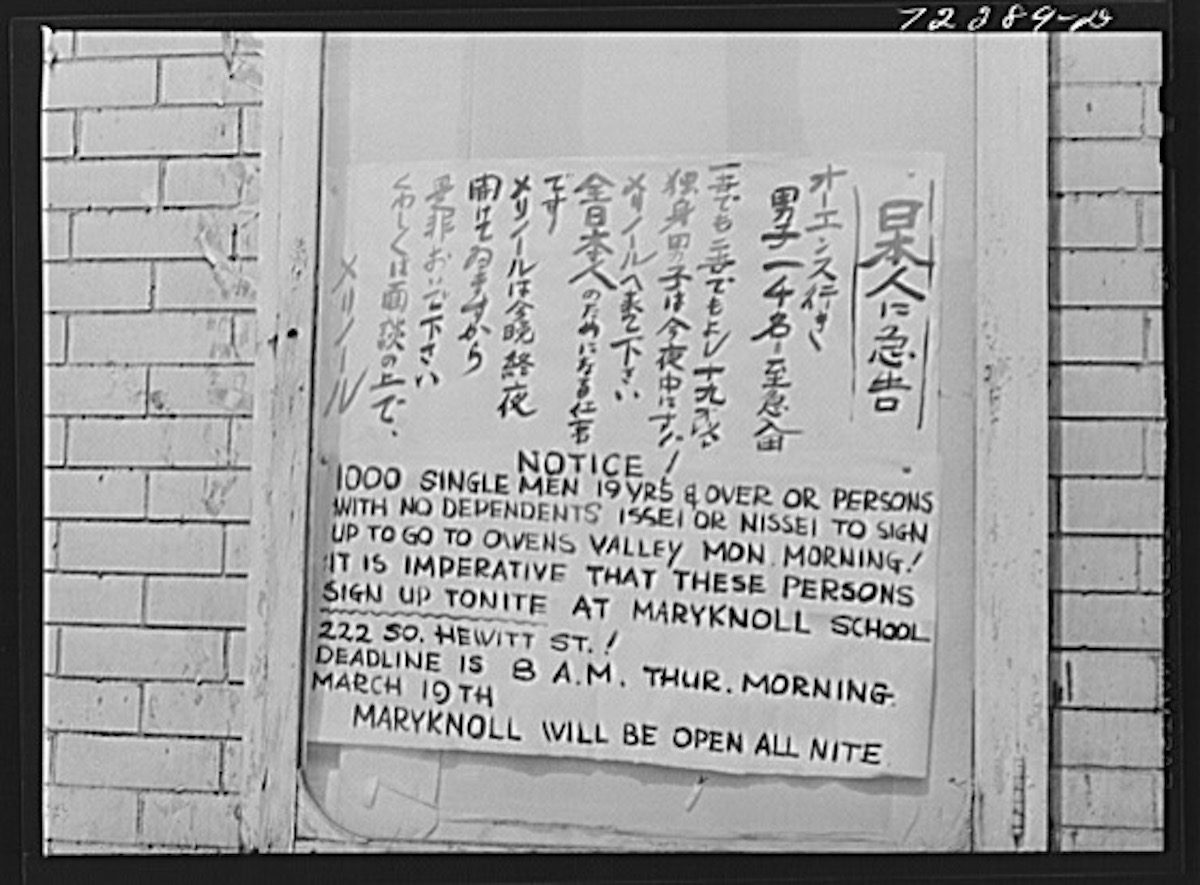

The Japanese referred to in this sign were an advance group going to Owens Valley for construction work – Russell Lee

San Benito County, California. Japanese-American who is working in field while awaiting final evacuation orders by Russell Lee 1942 May.

San Benito County, California. Japanese-American who is working in field while awaiting final evacuation orders by Russell Lee 1942 May.

Via: LoC

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.