The quarto, Grande édition de luxe, of Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine. ou, Analyse électro-physiologique de l’expression des passions des arts plastiques was sold by subscription. The first copies issued were illustrated by albumen prints (a type of photographic print made from paper coated with albumen (egg white) invented in 1850).

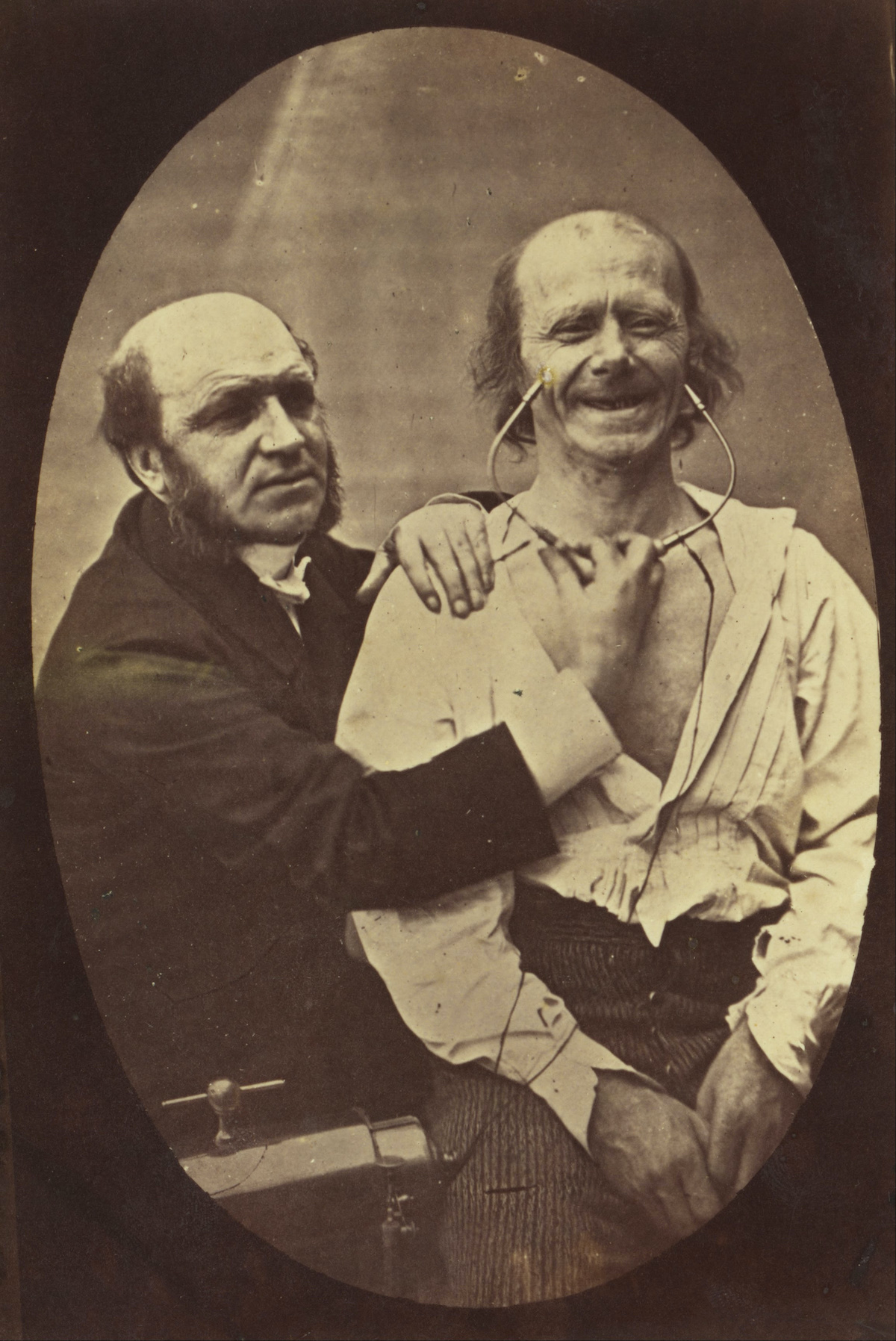

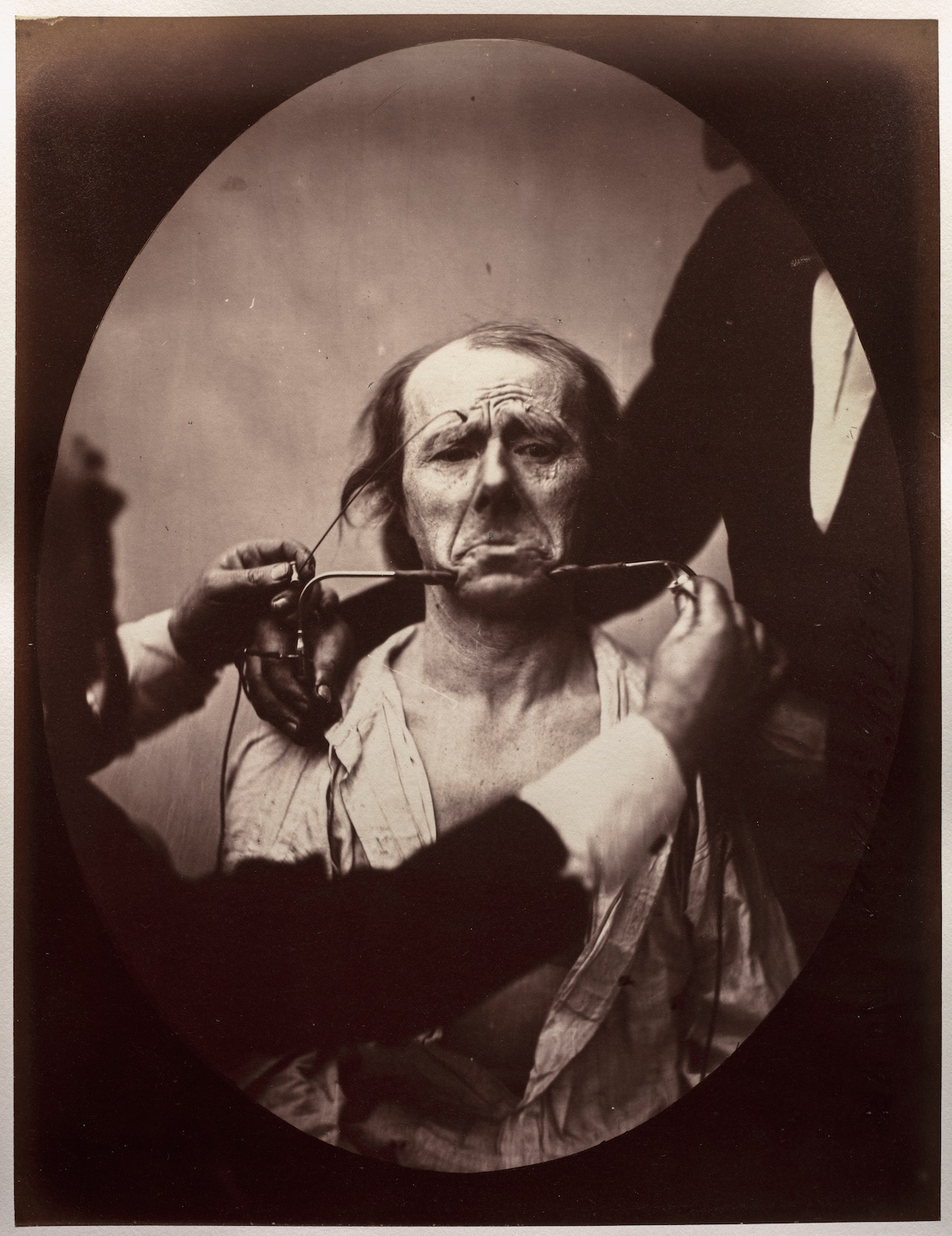

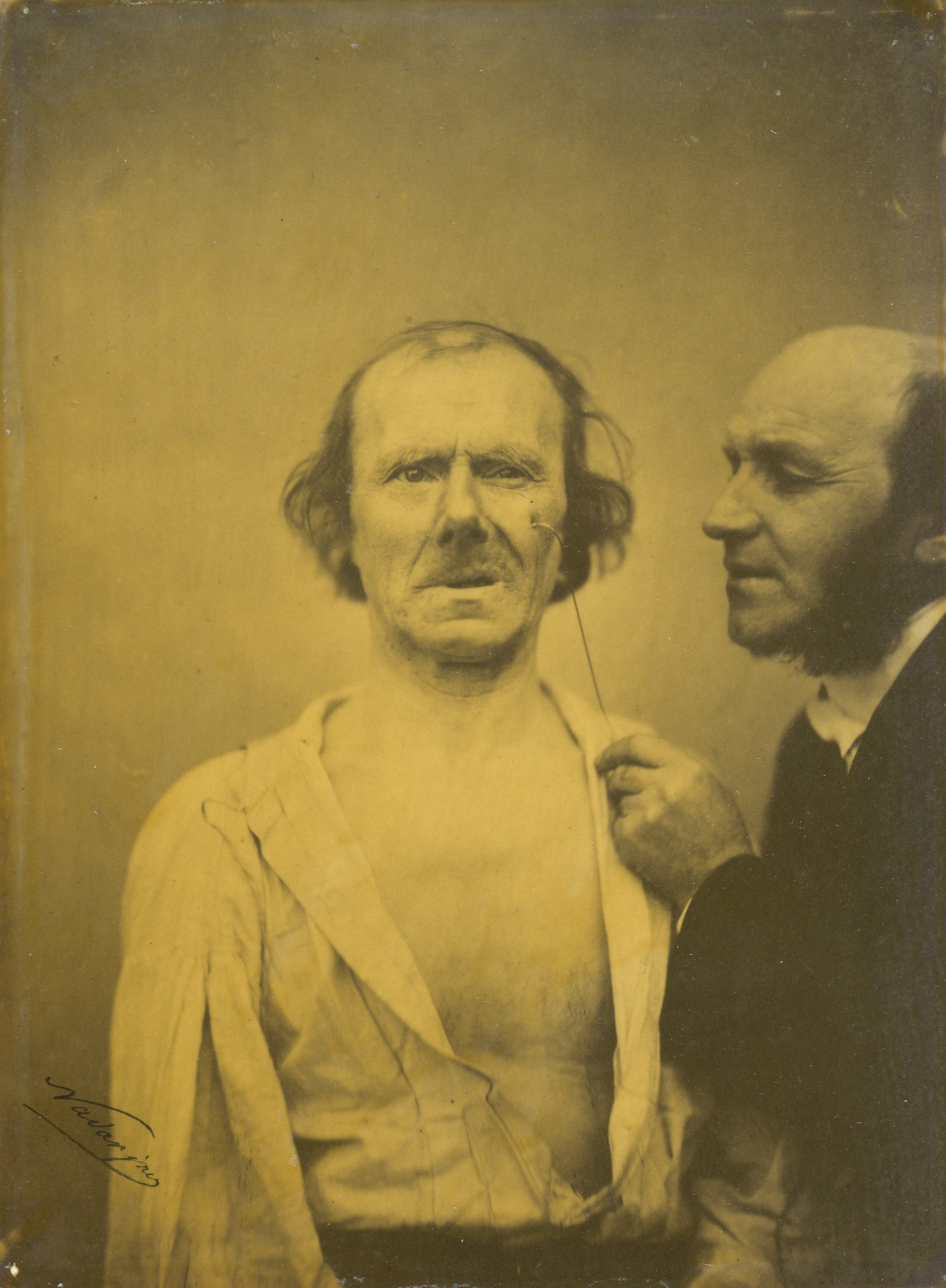

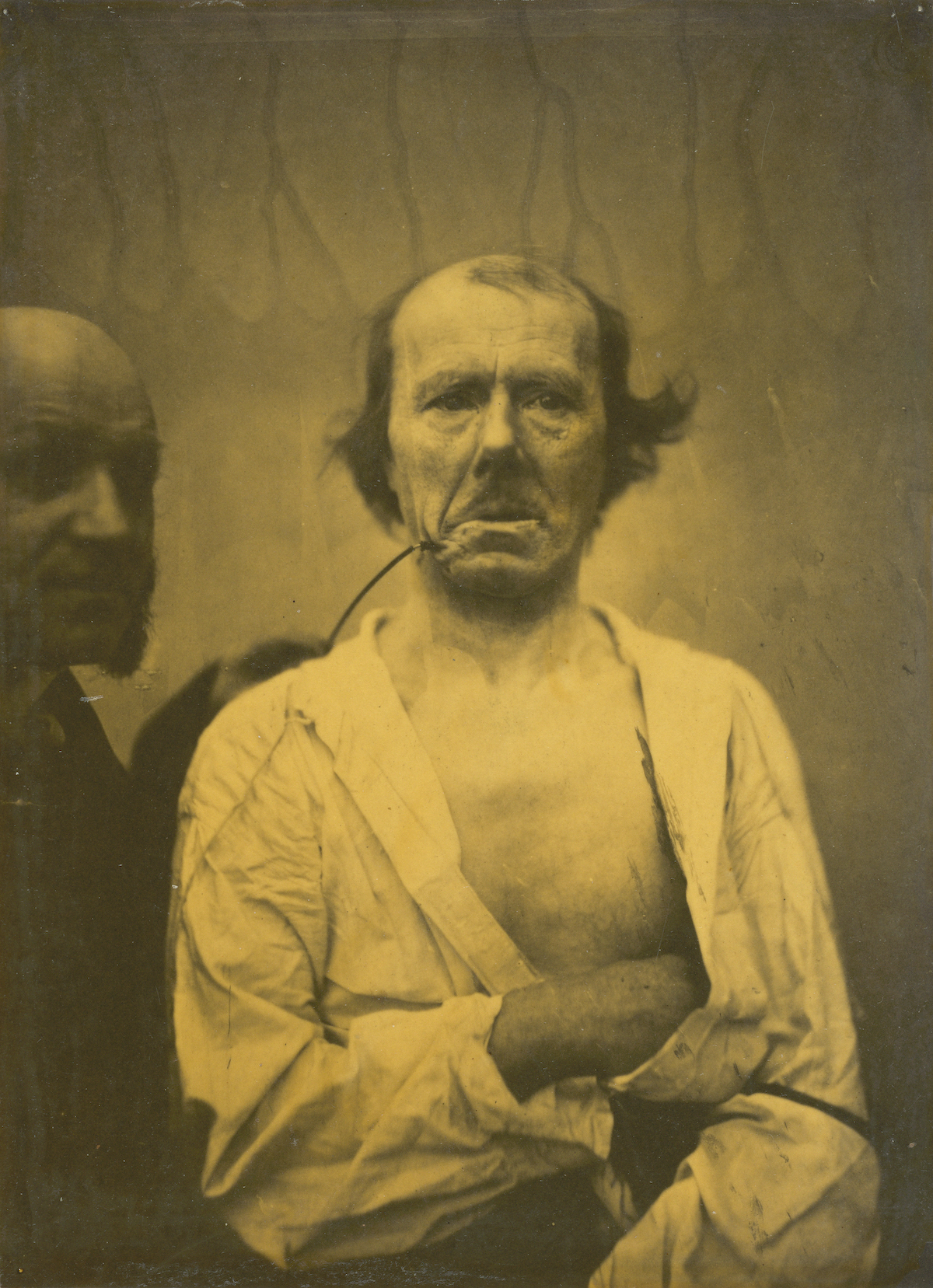

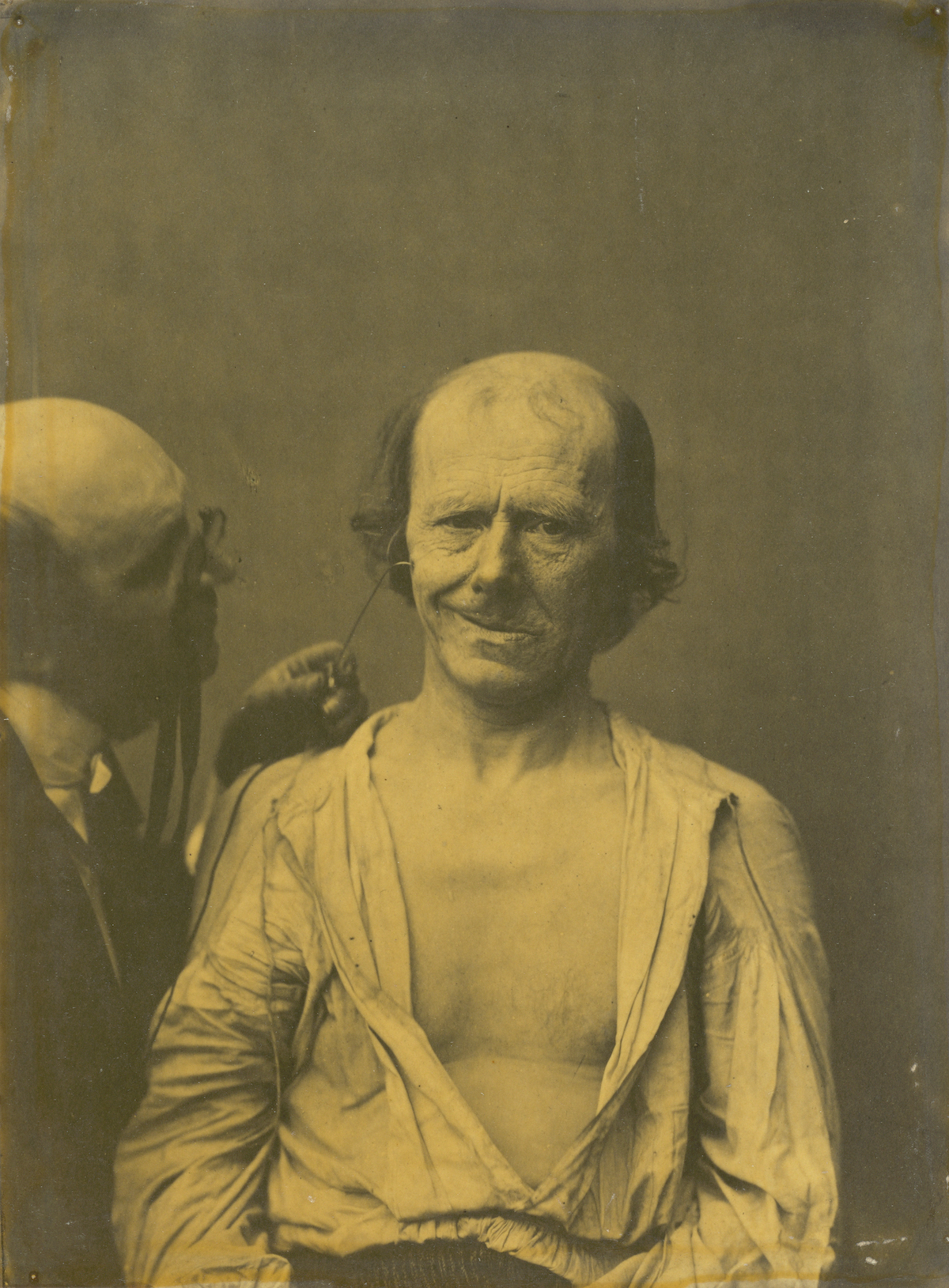

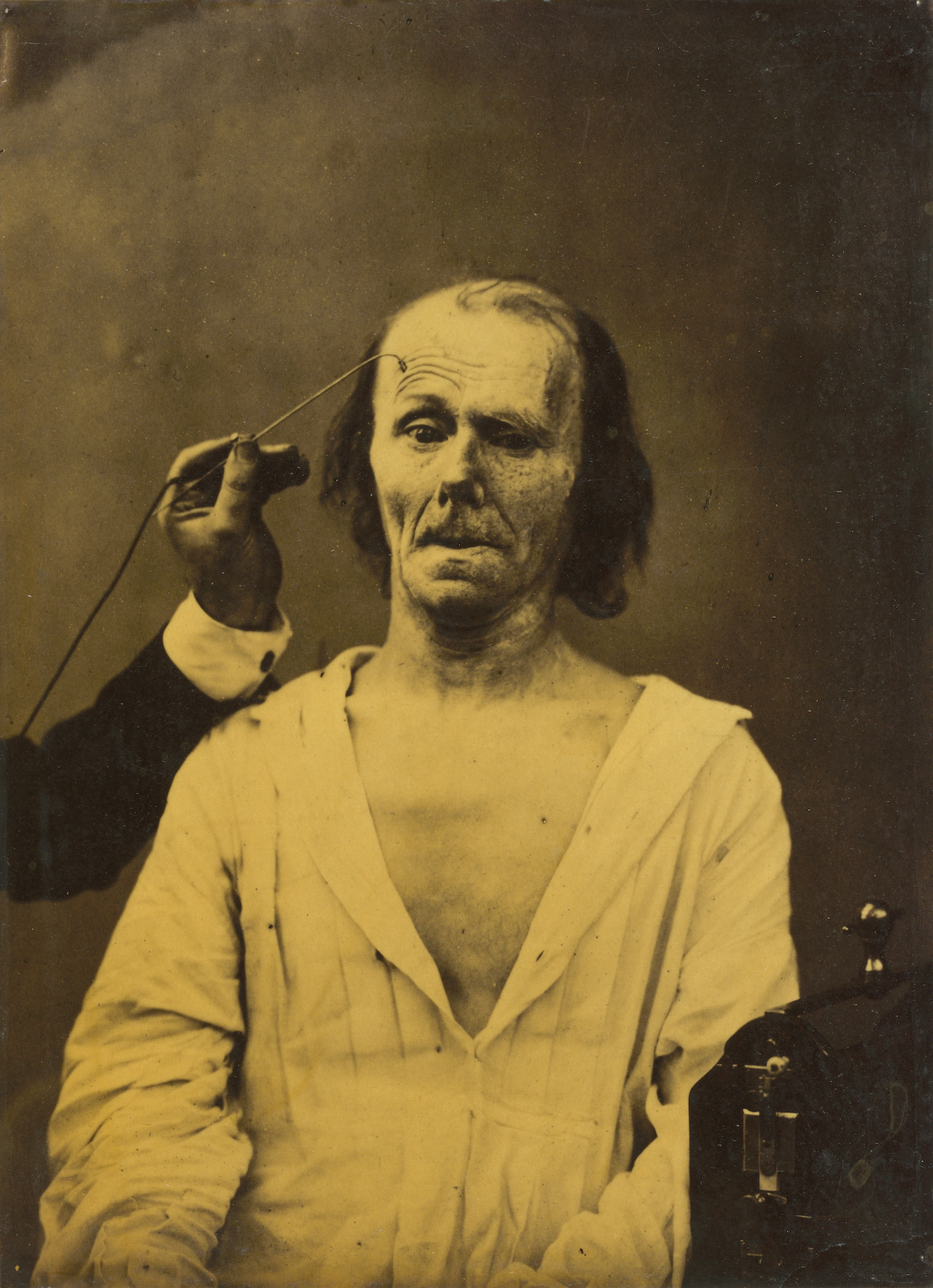

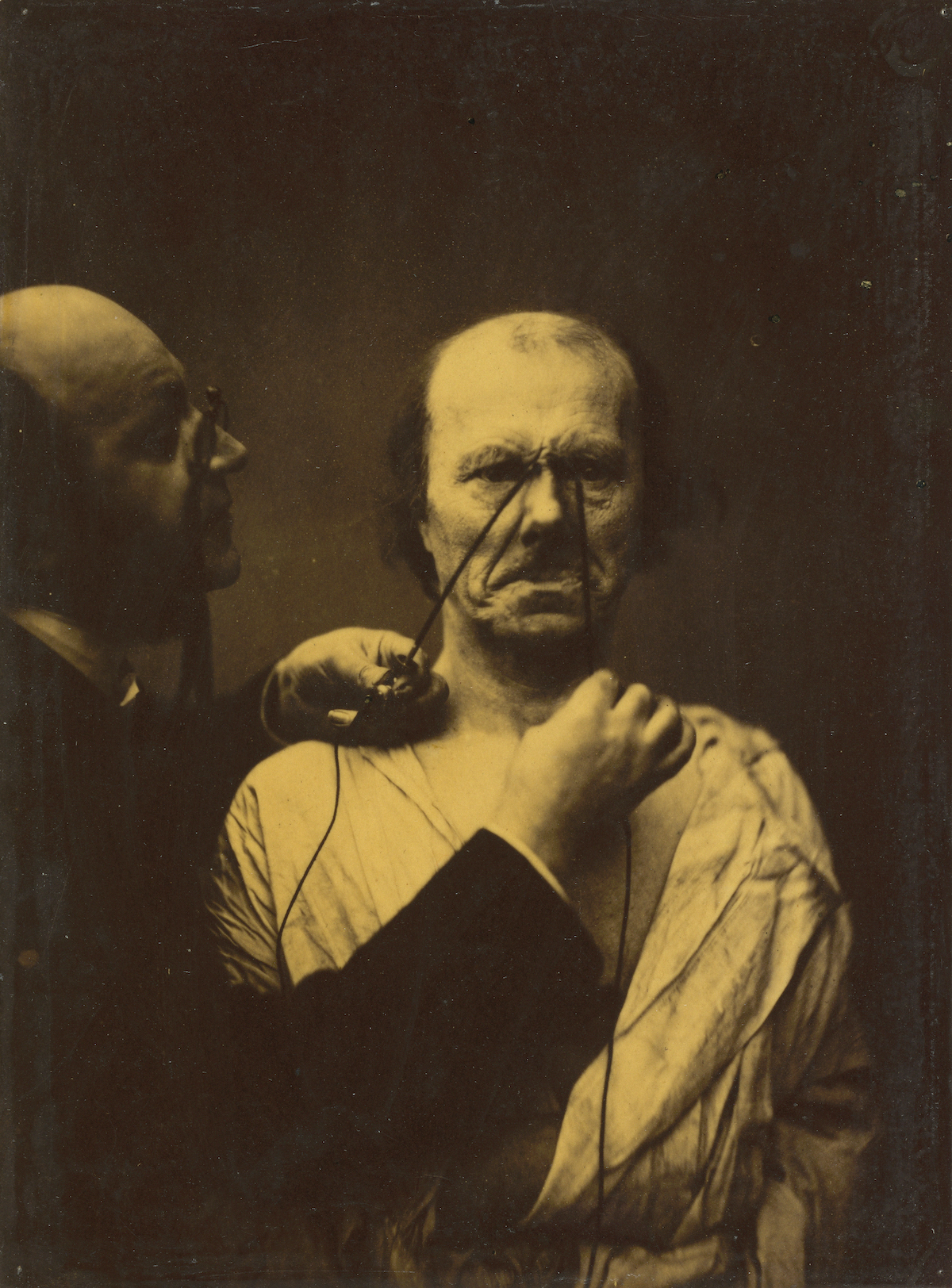

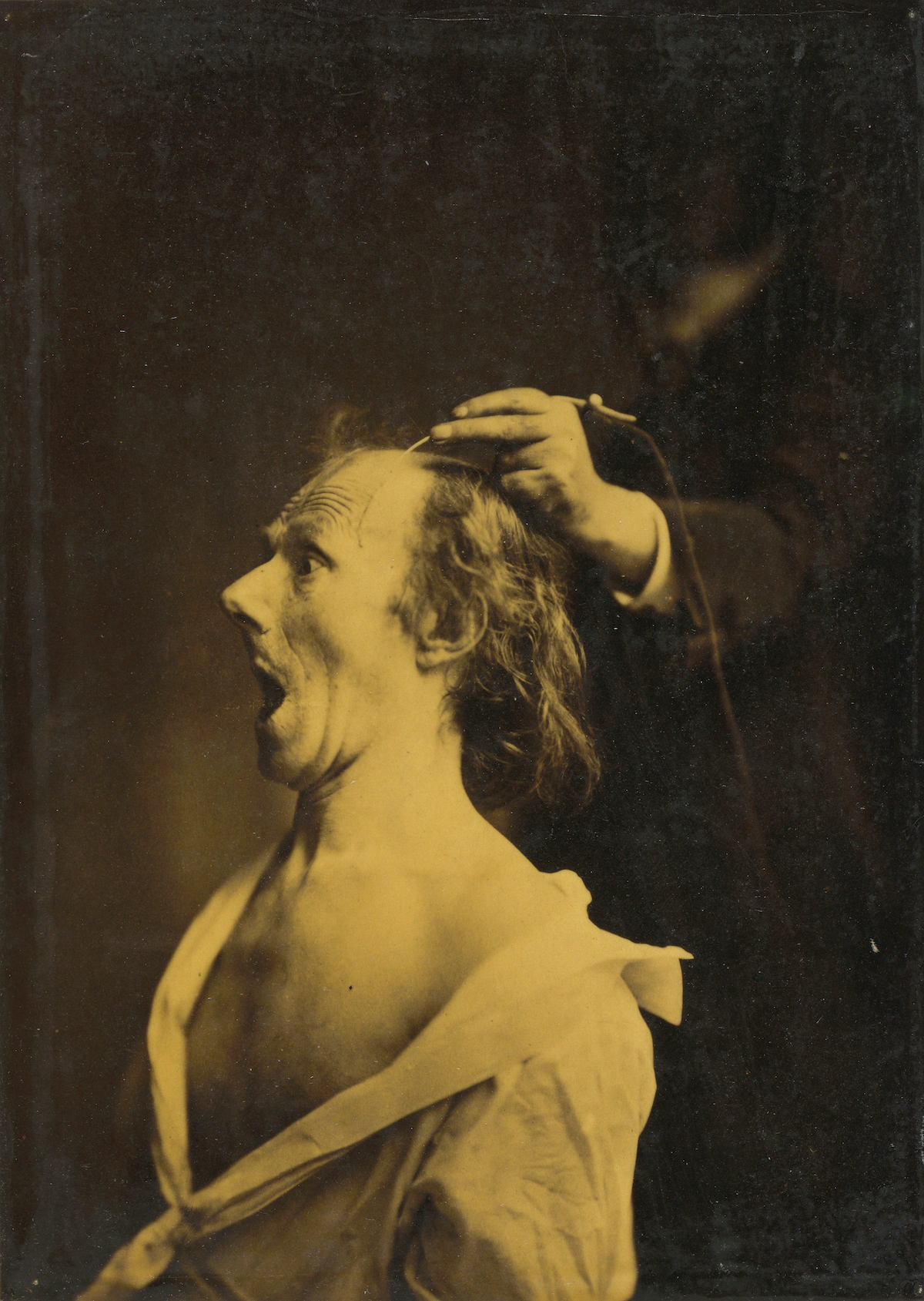

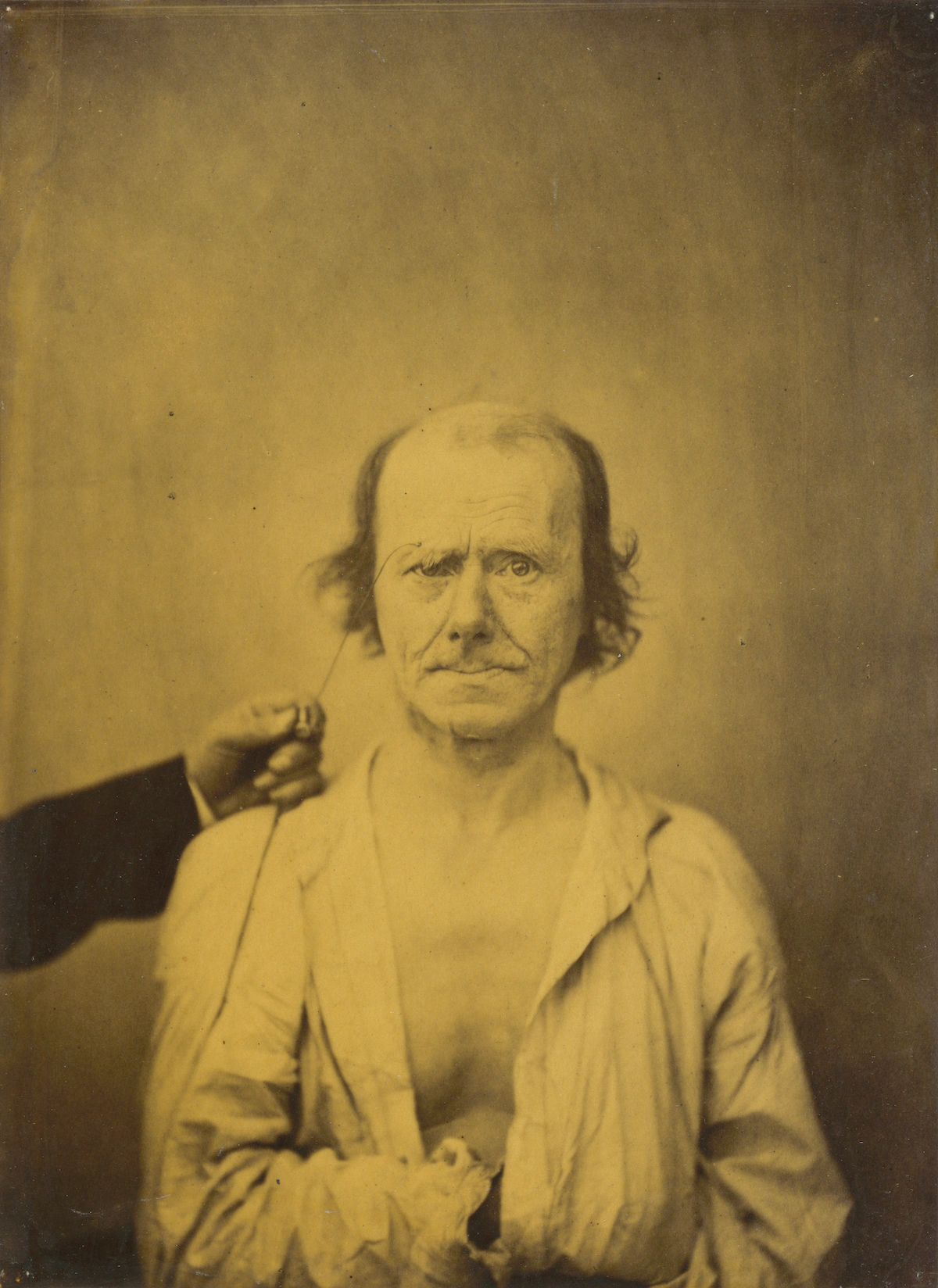

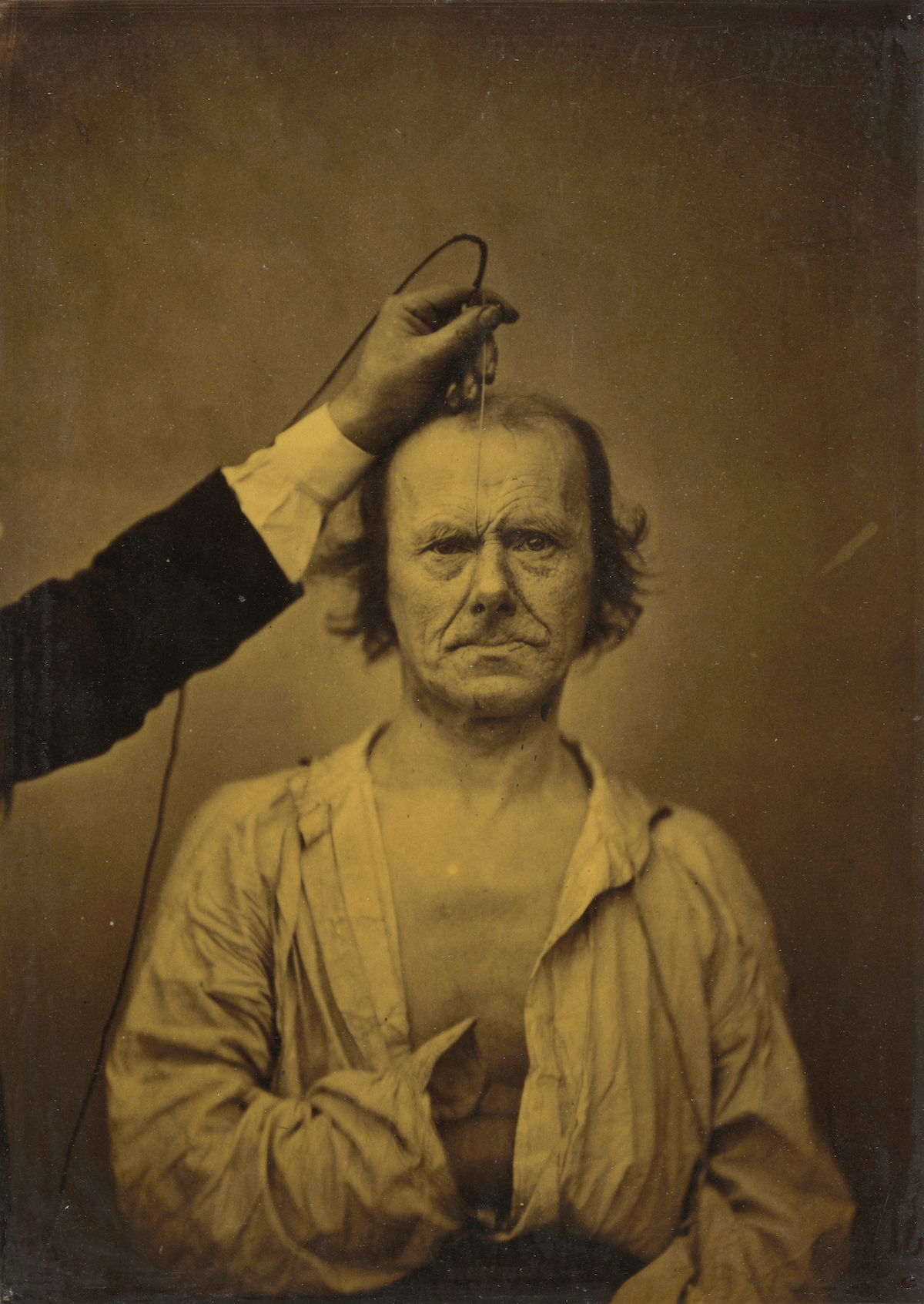

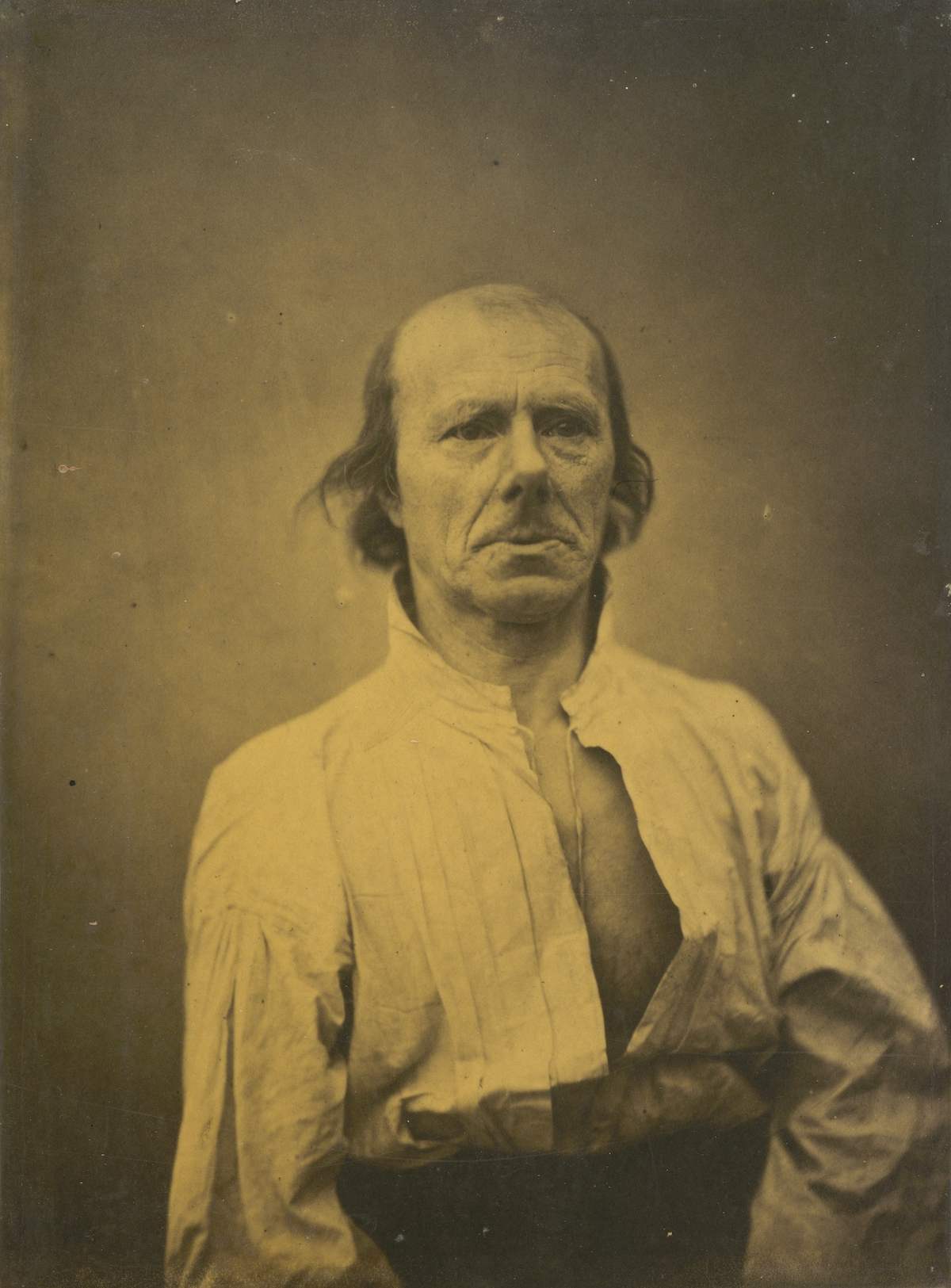

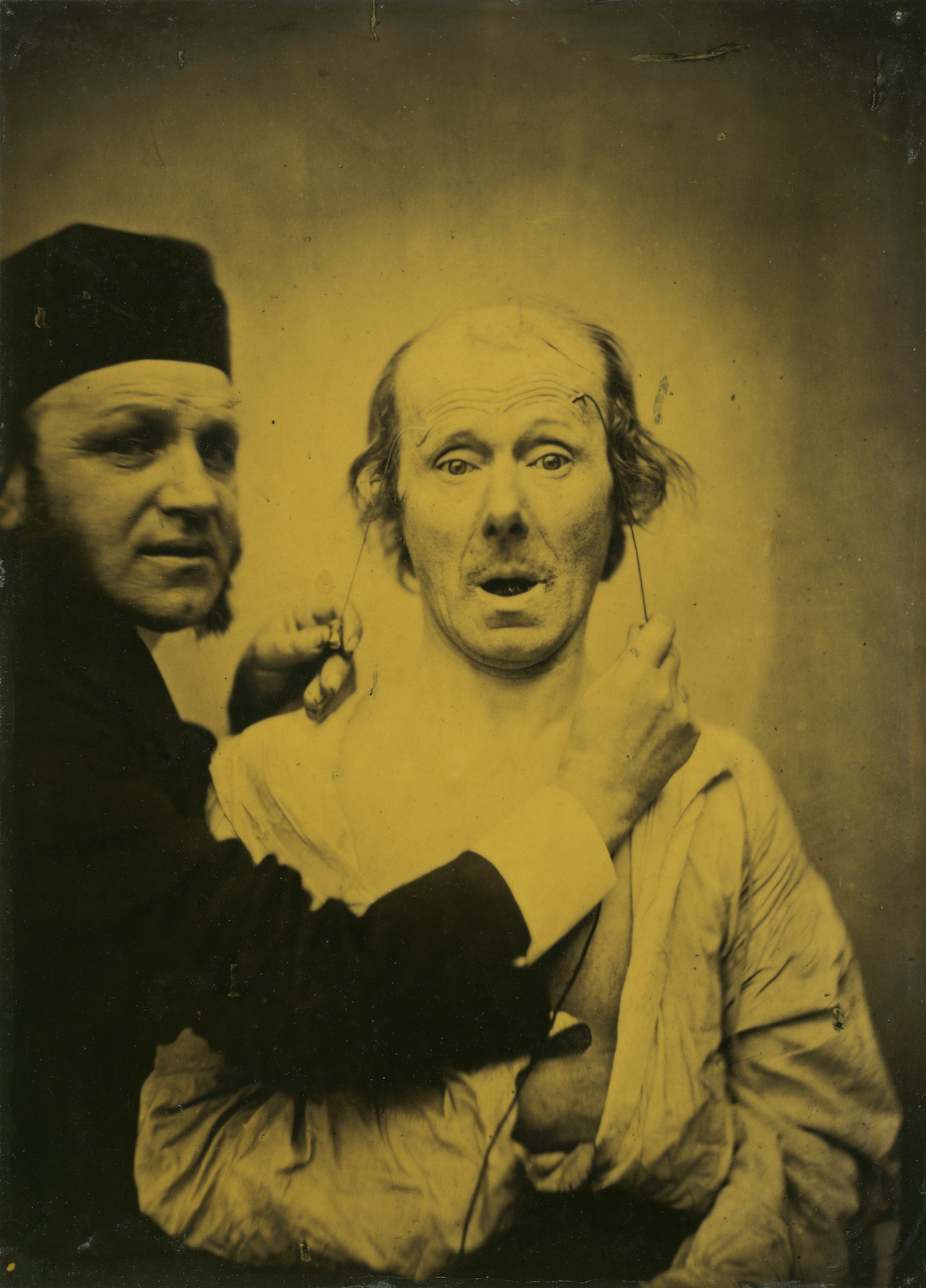

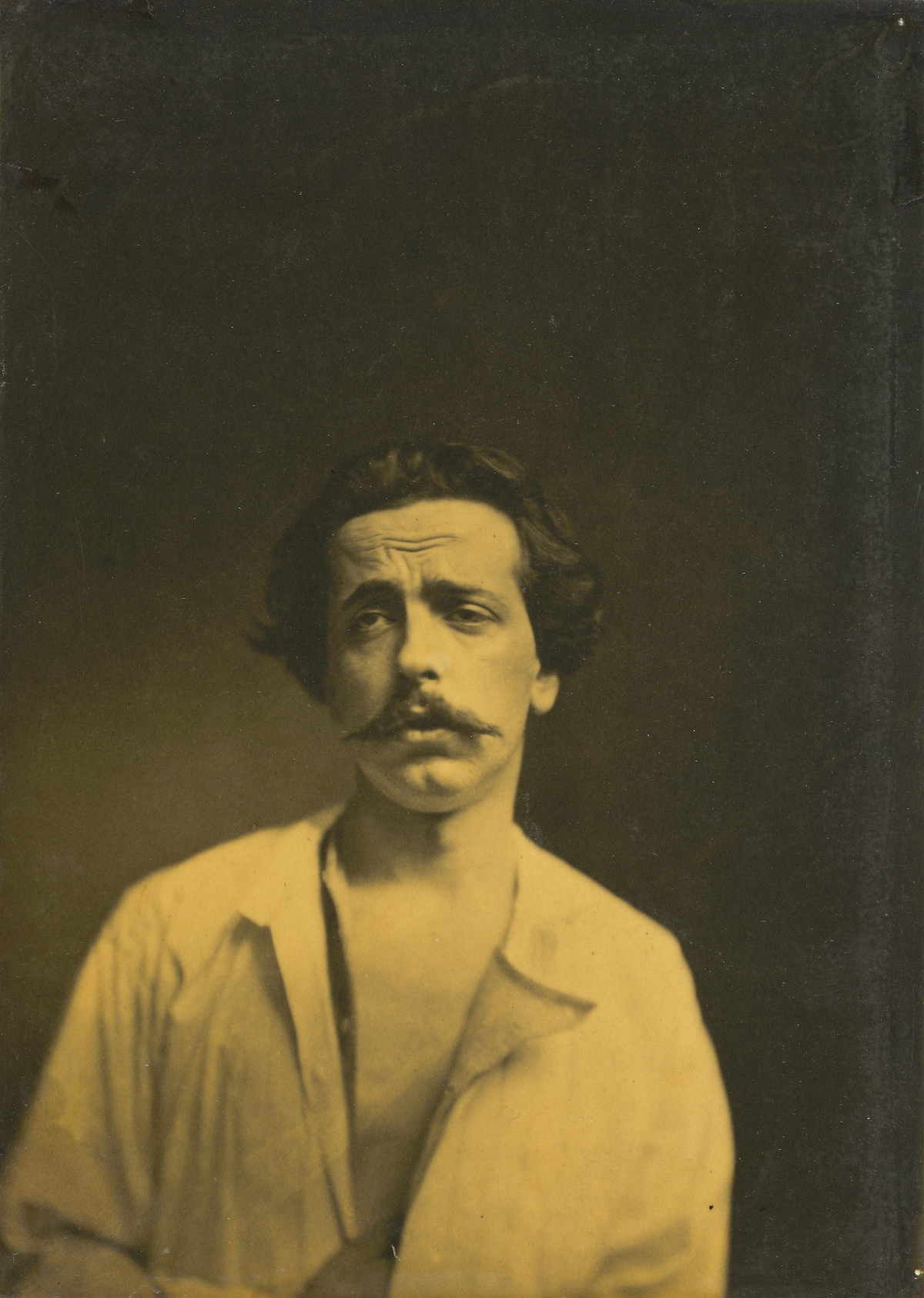

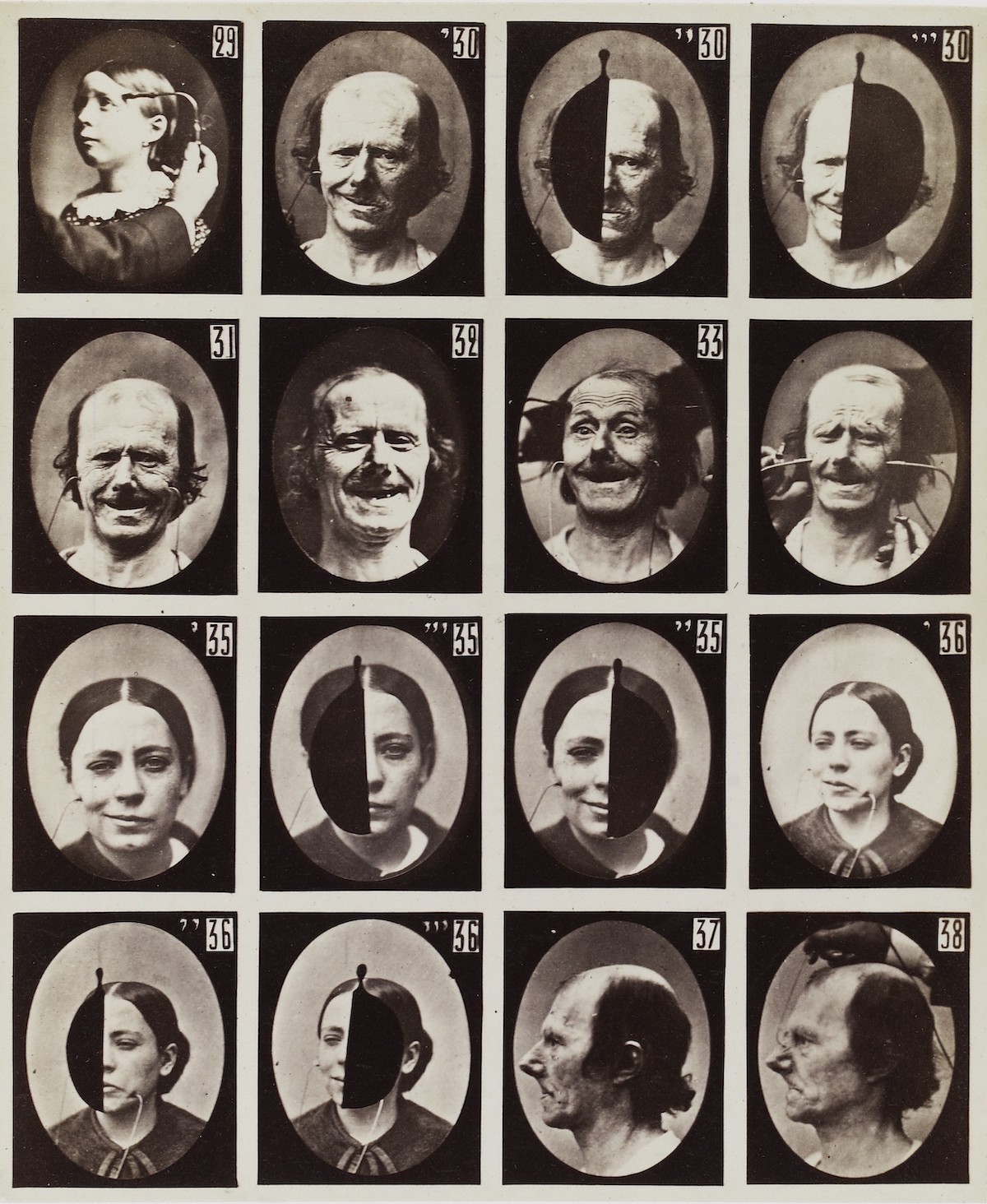

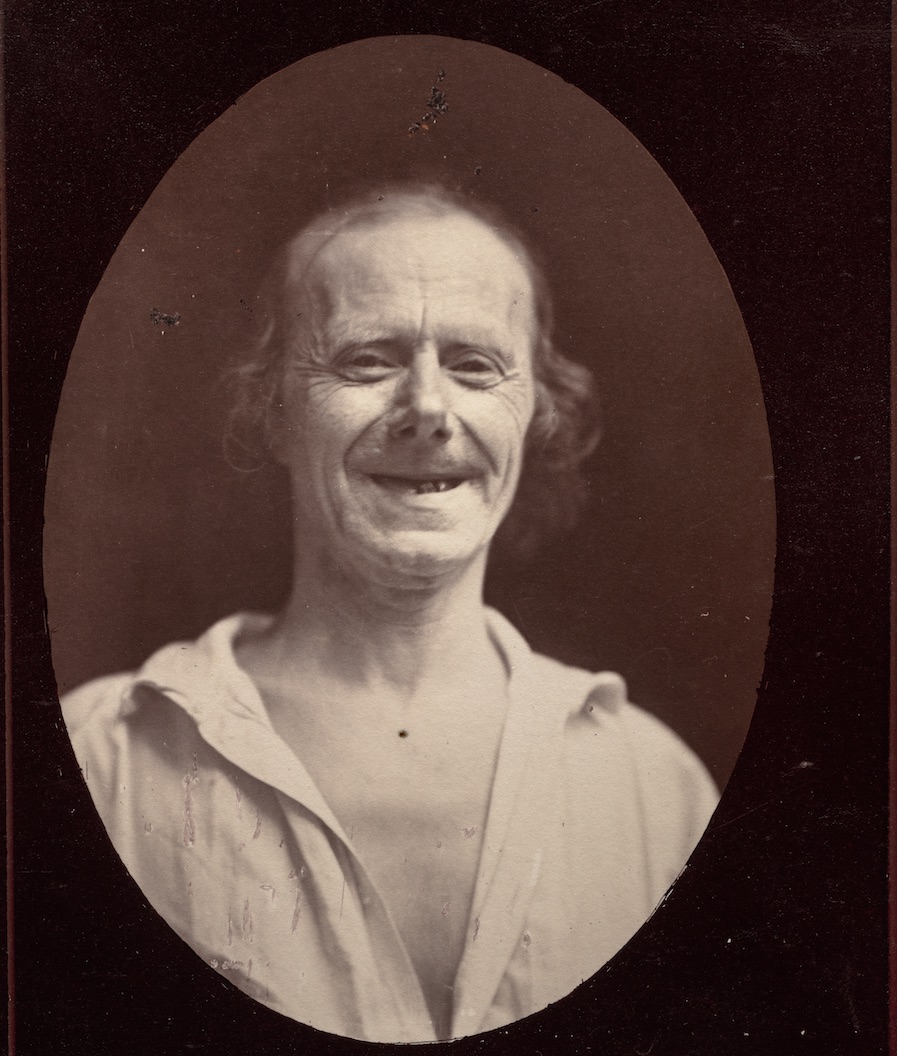

The book begins with a frontispiece portrait of the work’s author and scientist, Guillaume-Benjamin-Amand Duchenne de Boulogne (1806–75). with his subject, one of his patients, a former shoemaker, described as “an old, toothless man, with a thin face, whose features, without being absolutely ugly, approached ordinary triviality.” He, said Duchenne, was proof that “every human face could become spiritually beautiful through the accurate rendering of his or her emotions.”

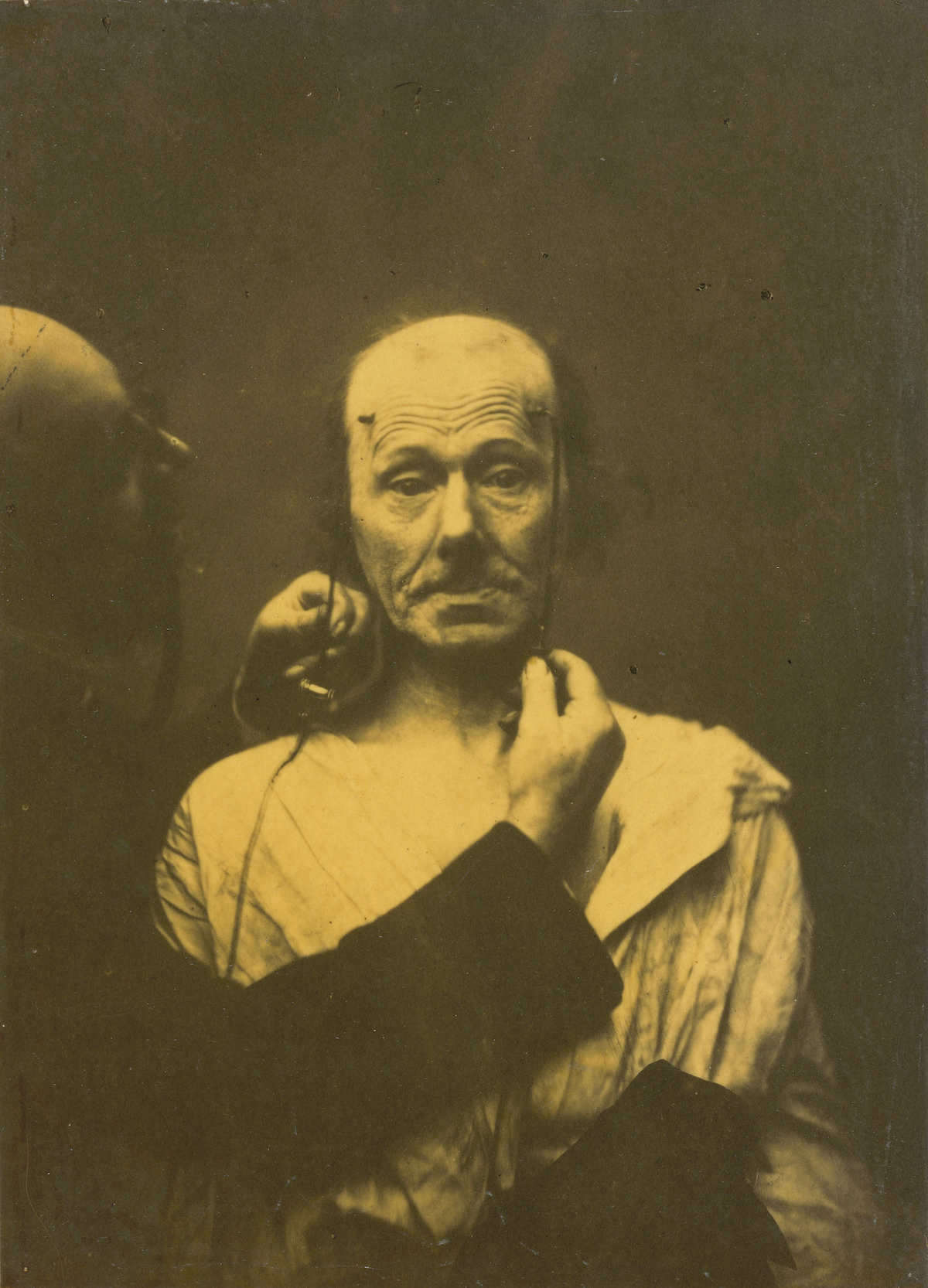

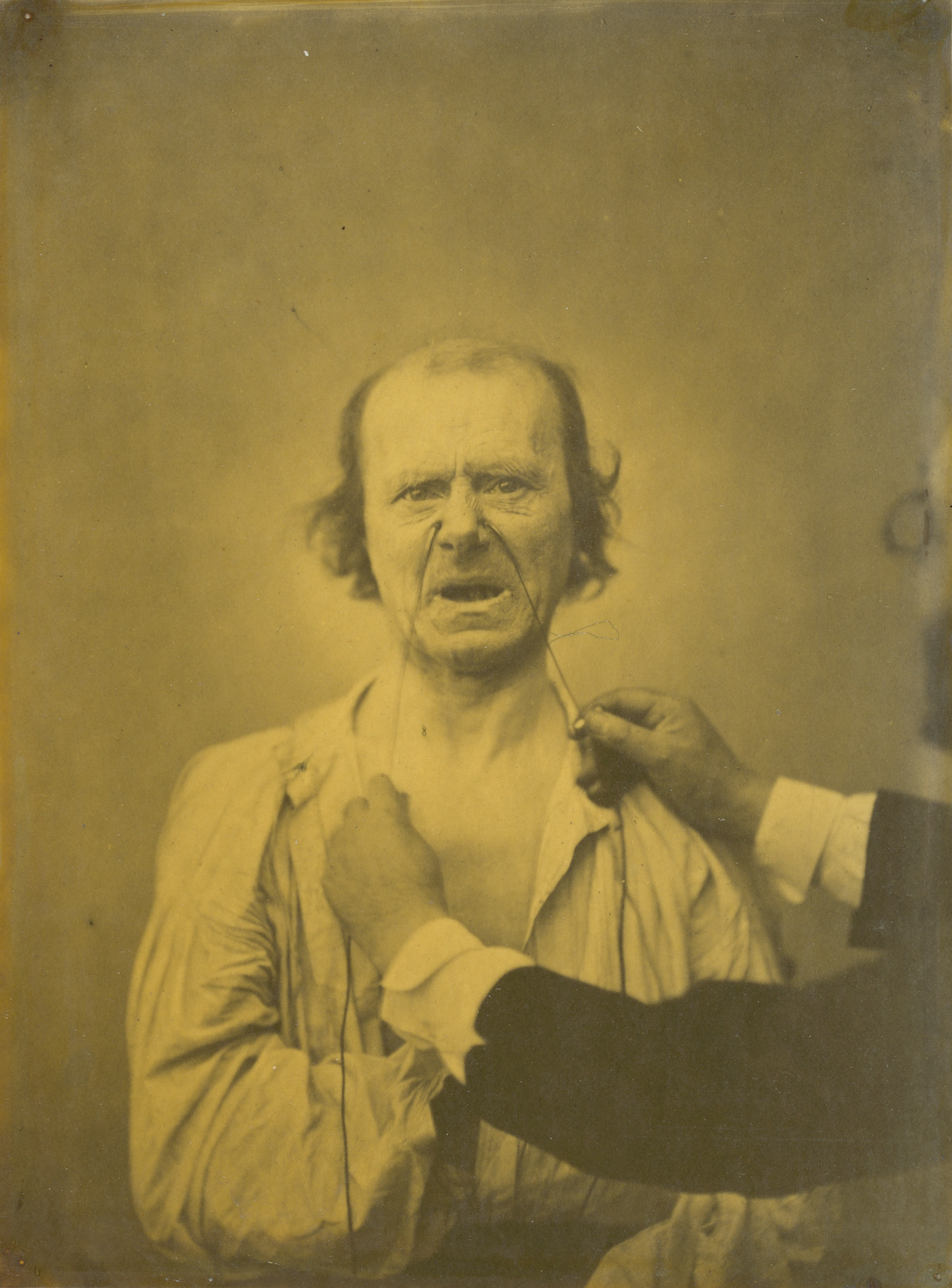

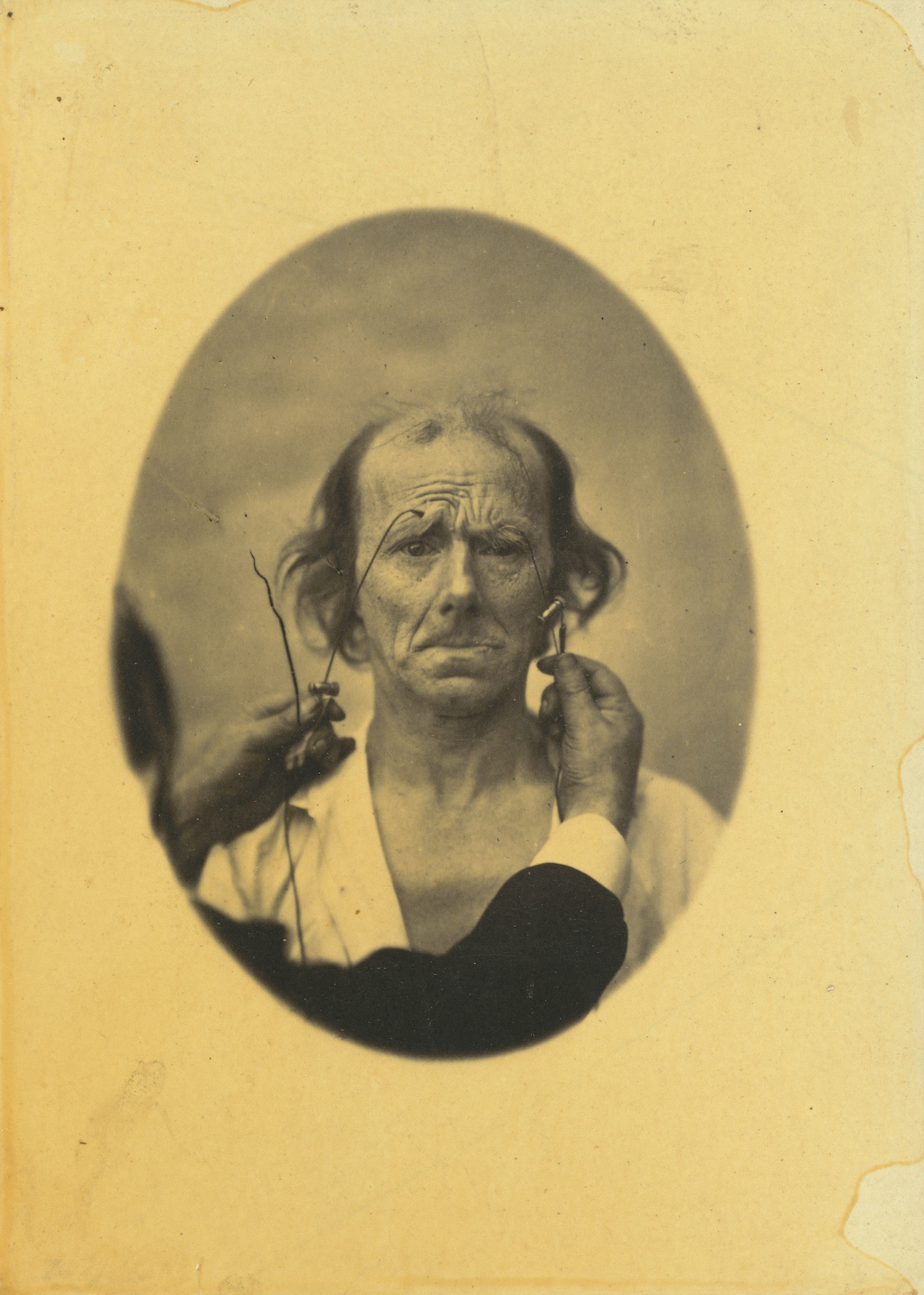

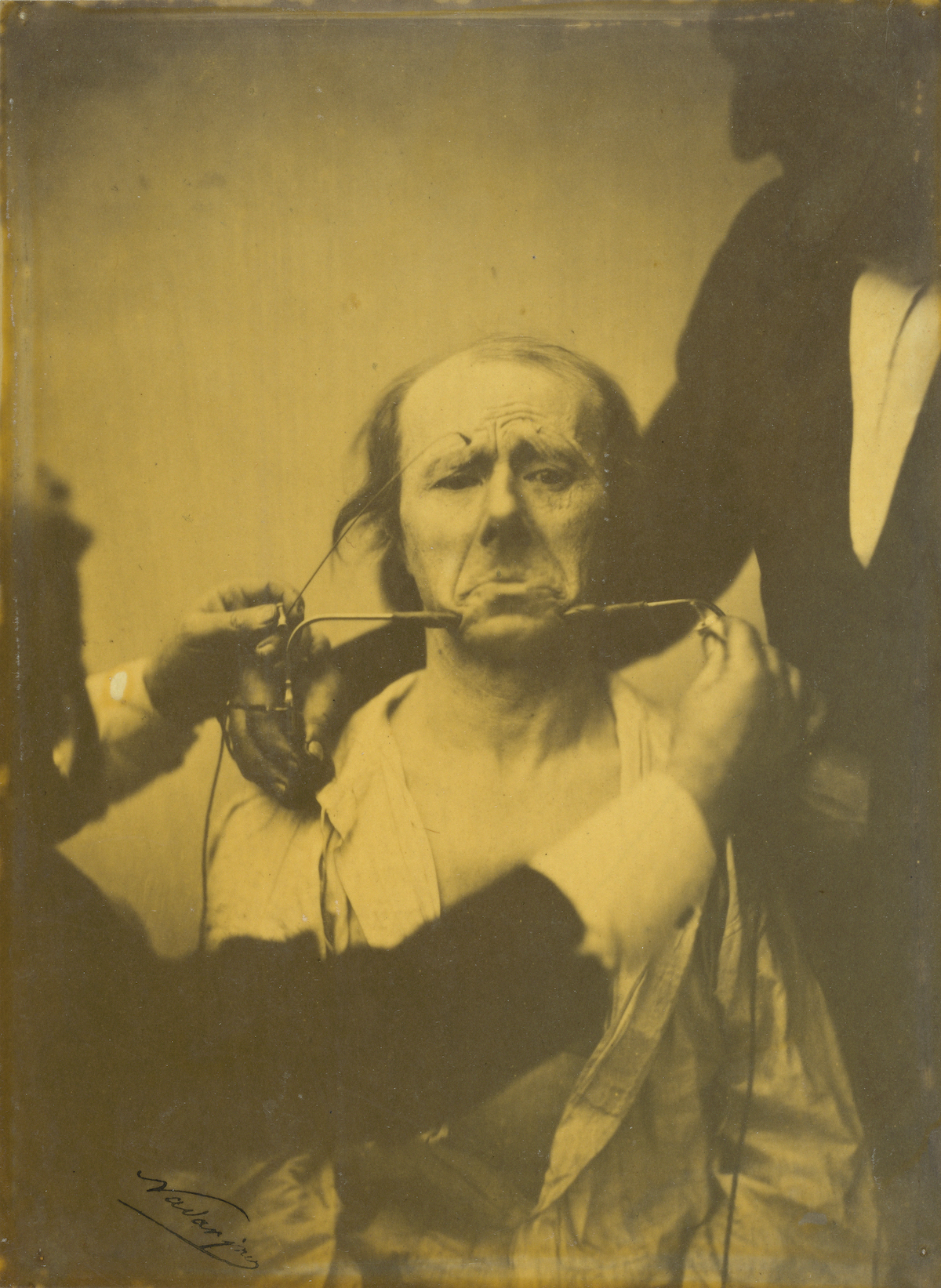

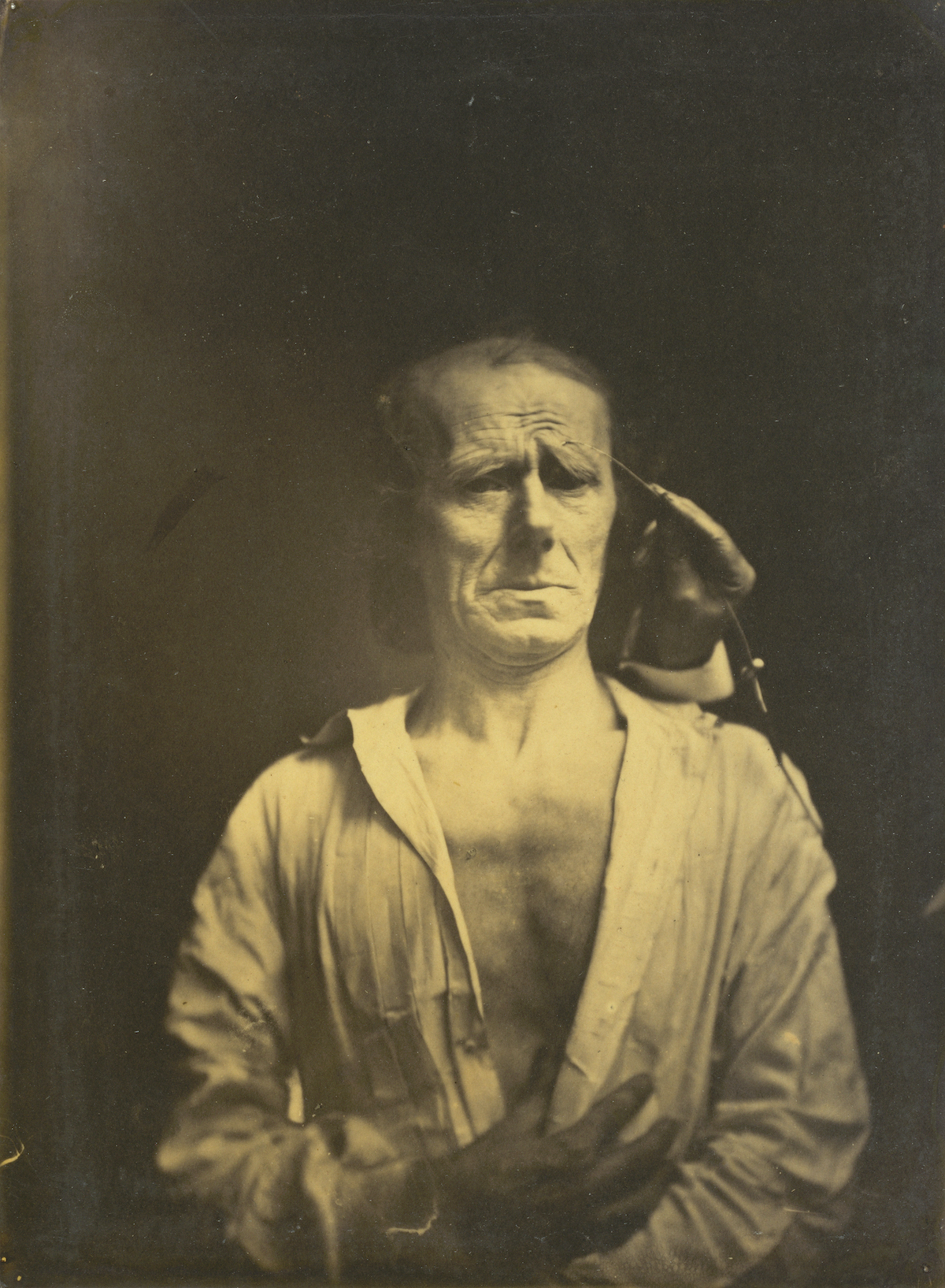

And so begins Duchenne illustrated scientific exploration of the physiology of human facial expression. He used electrodes on willing patients to contract facial muscles to convey 13 emotions. His intent was to teach artists how to portray those emotions.

Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine. ou, Analyse électro-physiologique de l’expression des passions des arts plastiques first appeared as an abstract published in Archives générales de médecine in 1862 and was then published in three formats: two octavo editions and one quarto edition. The work was a resource used by Charles Darwin (1809–82) for his own study on the genetics of behaviour, titled The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals, and in recent years it has been reclaimed as an important landmark in the history of the photographic arts.

Like physiognomists and phrenologists before him, Duchenne thought your face revealed your inner psyche. To understand the human face was to get closer to knowing the person’s soul. Through a reading of the expressions alone (pathognomy), he could make an “accurate rendering of the soul’s emotions”. Expressions were the “gymnastics of the soul”.

He would record his experiments through photography. “Only photography,” he wrote, “as truthful as a mirror, could attain such desirable perfection.”

Duchenne writes:

In the face our creator was not concerned with mechanical necessity. He was able in his wisdom or – please pardon this manner of speaking – in pursuing a divine fantasy … to put any particular muscles into action, one alone or several muscles together, when He wished the characteristic signs of the emotions, even the most fleeting, to be written briefly on man’s face. Once this language of facial expression was created, it sufficed for Him to give all human beings the instinctive faculty of always expressing their sentiments by contracting the same muscles. This rendered the language universal and immutable.

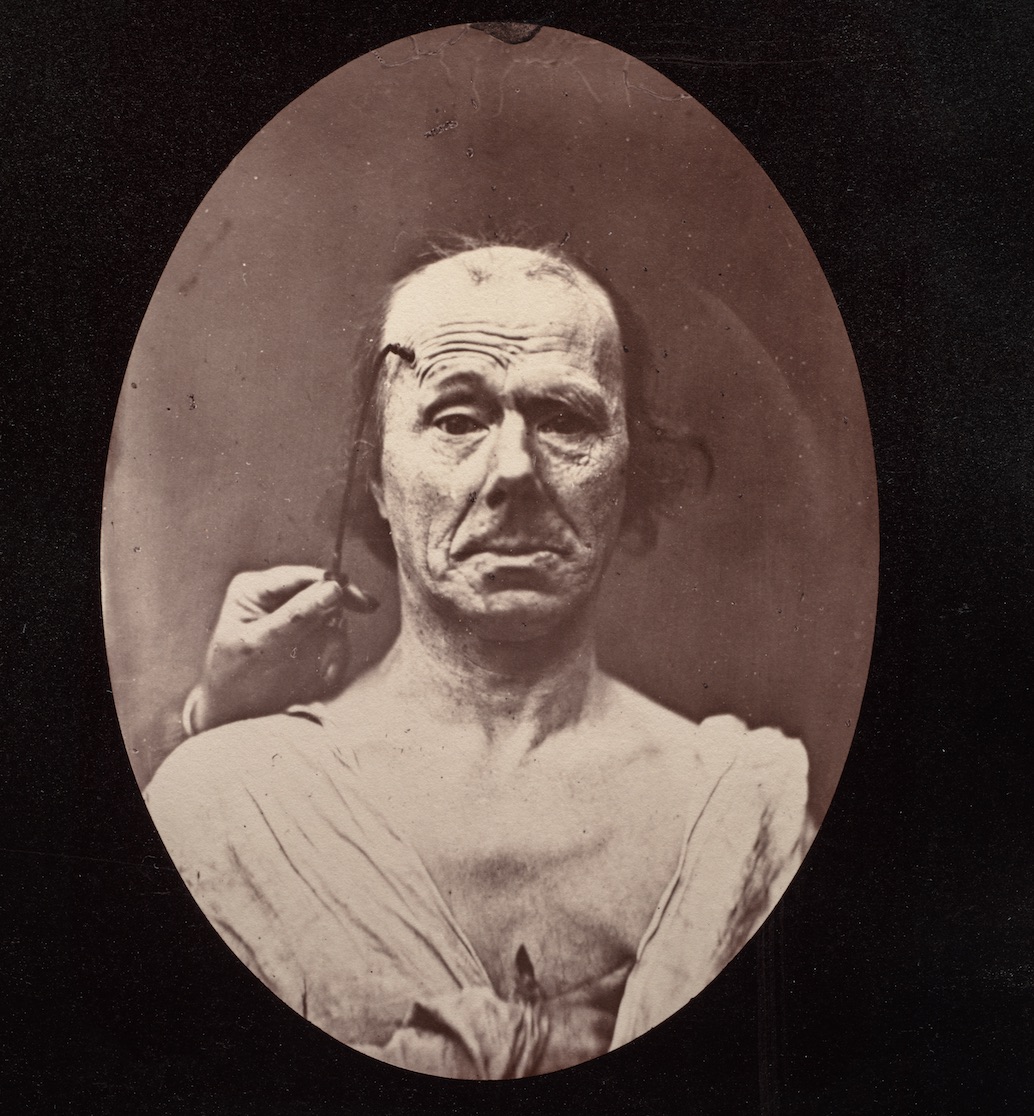

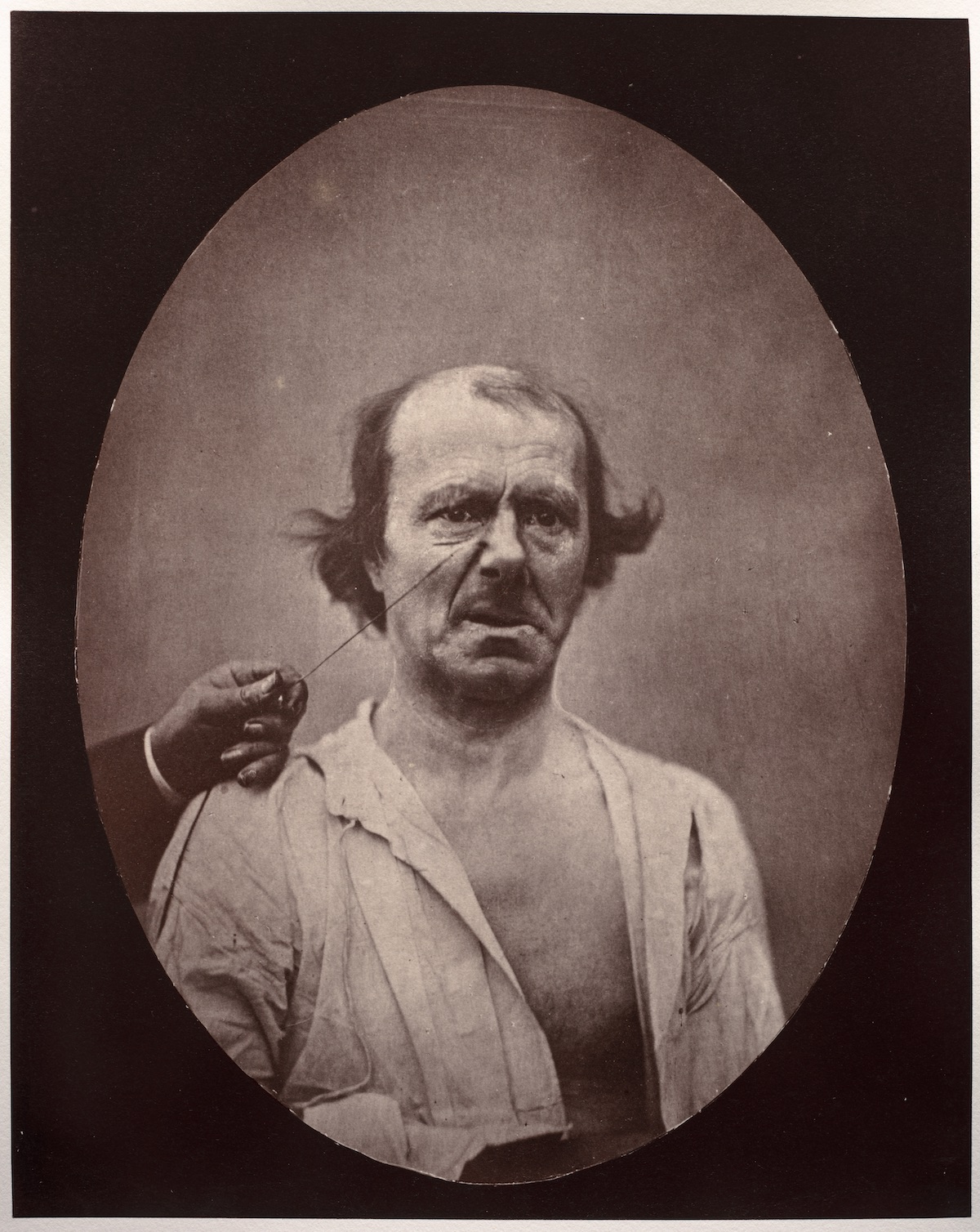

Duchenne noted 13 primary emotions the expressions controlled by one or two muscles. He isolated the precise contractions used to produce each expression, separating them into two categories: partial and combined. To stimulate the facial muscles and capture these “idealized” expressions of his patients, Duchenne applied faradic shock through electrified metal probes pressed upon the surface of the various muscles of the face.

Adrian Tournachon, (the brother of Felix Nadar), was hired to photograph the experiments. Mechanism of Human Physiognomy was the first publication on the expression of human emotions to be illustrated with actual photographs.

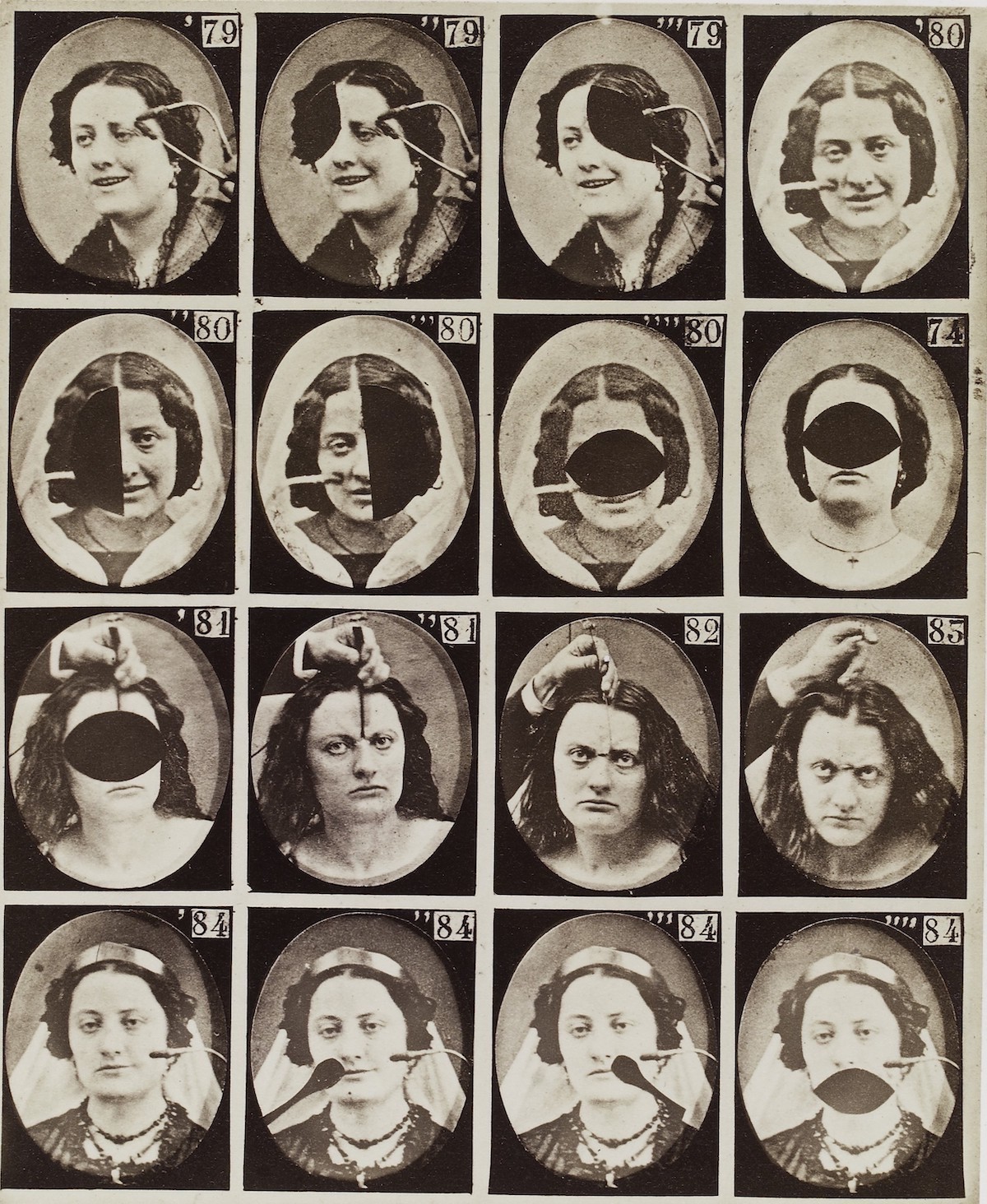

Whereas the scientific section was intended to exhibit the expressive lines of the face and the “truth of the expression”, the book’s aesthetic section was intended also to demonstrate that the “gesture and the pose together contribute to the expression; the trunk and the limbs must be photographed with as much care as the face so as to form an harmonious whole”. For these plates Duchenne used a partially blind young woman who he claimed “had become accustomed to the unpleasant sensation of this treatment …”.

Duchenne advised that looking at both sides of the face simultaneously would reveal only a “mere grimace” and he urged the reader to examine each side separately and with care.

“Weeping, tears of pity (left); Relaxed face (right)”

“A relaxed expression (left); Disgust (right)”

Icono-photographique. Mécanisme de la Physionomie Humaine.

“False joy or laughter (right)”

“A relaxed face (left); Profound attention (right)”

“Aggression, wickedness”

“Astonishment, stupefaction, amazement”

“ttention (left); Reflection (right)”

“Attention (left); Severity, aggression (right)”

“Attention”

“Guillaume-Benjamin-Amant Duchenne (de Boulogne), Discontent, bad humor, 1854-1856, albumen print, printed 1862, image: 22.7 × 16.7 cm (8 15/16 × 6 9/16 in.)

mount: 43 × 27.9 cm (16 15/16 × 11 in.), Edward E. MacCrone Fund, 2015.52.32″

“Guillaume-Benjamin-Amant Duchenne (de Boulogne), Dissatisfaction, somber thoughts (left); Reflection (right), 1854-1856, albumen print, printed 1862, image: 22.1 × 15.9 cm (8 11/16 × 6 1/4 in.)

mount: 40.4 × 27.7 cm (15 7/8 × 10 7/8 in.), Eugene L. and Marie-Louise Garbáty Fund, 2015.52.19″

“Face in repose”

“Pain and despair”

“No painful expression”

“Surprise”

“Terror mixed with pain, torture”

“Lascivious ideas and desires”

“This contraction of m. platysma alone lacks expression’

“Nun saying prayer”

“Severity”

“Memory of love or ecstatic gaze”

“Painful recollection or painful thoughts”

Figure 50: “Affected weeping and face in repose”

“False laughter”

“Scene of coquetry”

“Painful memories”

“Attention”

https://clevelandart.org/art/2018.9

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.