“In 1931,” wrote British historian Arnold Toynbee, “men and women all over the world were seriously contemplating and frankly discussing the possibility that the Western system of Society might break down and cease to work.” As if to confirm that widespread anxiety, Mussolini proclaimed in the following year, “the liberal state is destined to perish. All the political experiments of our day are anti-liberal.” The following decade would reveal to the world the mass murderous designs behind that collapse.

Famed American journalist and writer Walter Lippmann agreed with Mussolini’s forecast, if not his motivations. When Hitler ascended to power in 1933, Lippmann told an audience at Berkeley, “The present century is the century of authority, a century of the Right, a Fascist century.” Lippmann ostensibly stood on the side of liberalism, though his was a decidedly top-down variety. Critical of democratic idealism, he argued in 1919, three years before the rise of Mussolini’s Fascism, that government and corporate elites must shape the views of the public, steering the ships of state and market by telling people what is in their best interest.

As influential as the work of writers like Lippmann and his disciple Edward Bernays was on the fields of advertising and public communications, it also appealed to political propagandists intent on shaping the 20th century into “a Fascist century.” Lippmann understood the dangers of the misuse of information, though he mostly saw that danger coming in the form of “Bolshevism.” As Hannah Arendt argued thirty years later in her diagnosis of totalitarianism, he wrote, “men who have lost their grip upon the relevant facts of their environment are the inevitable victims of agitation and propaganda. The quack, the charlatan, the jingo, and the terrorist, can flourish only where the audience is deprived of independent access to information.”

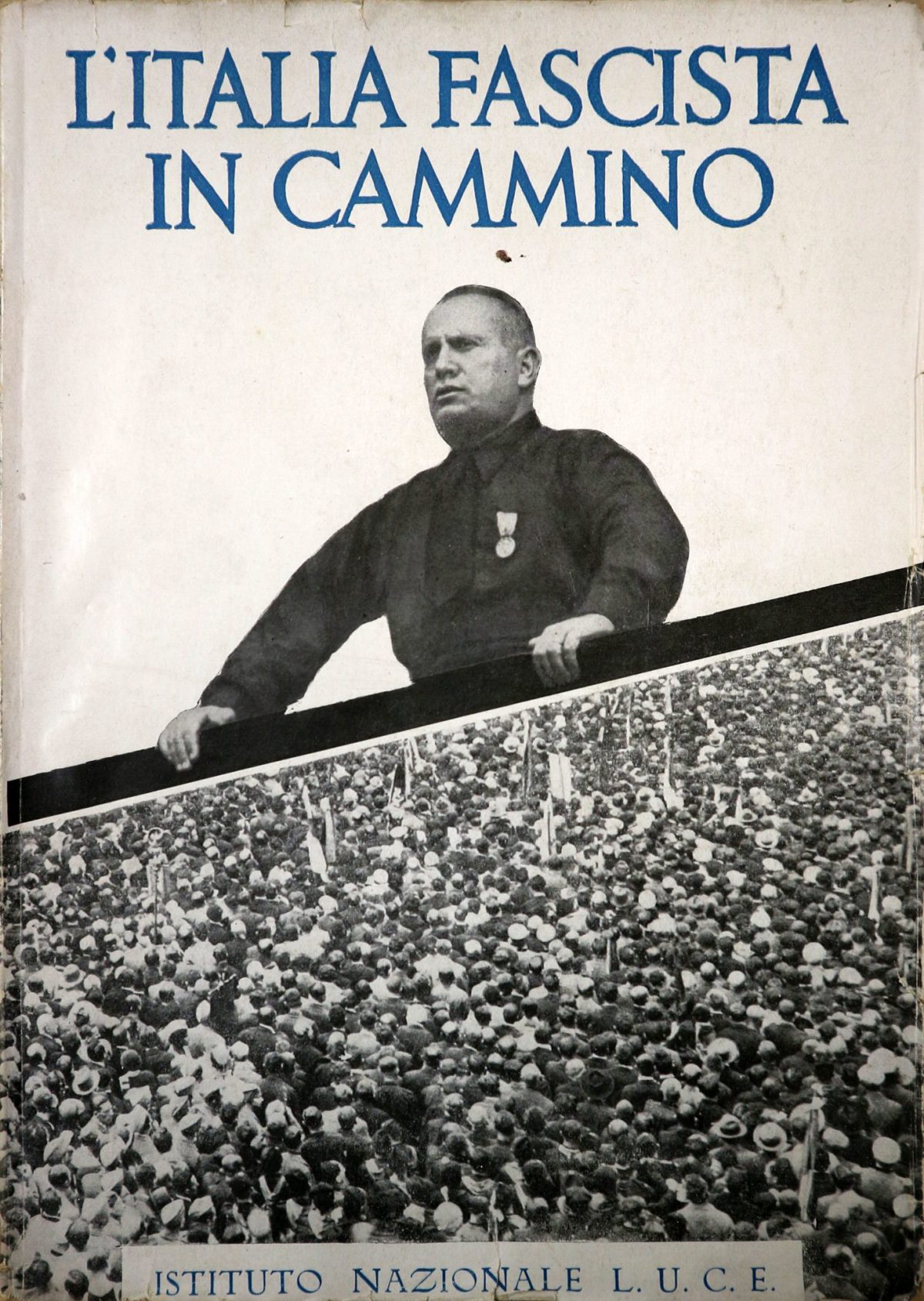

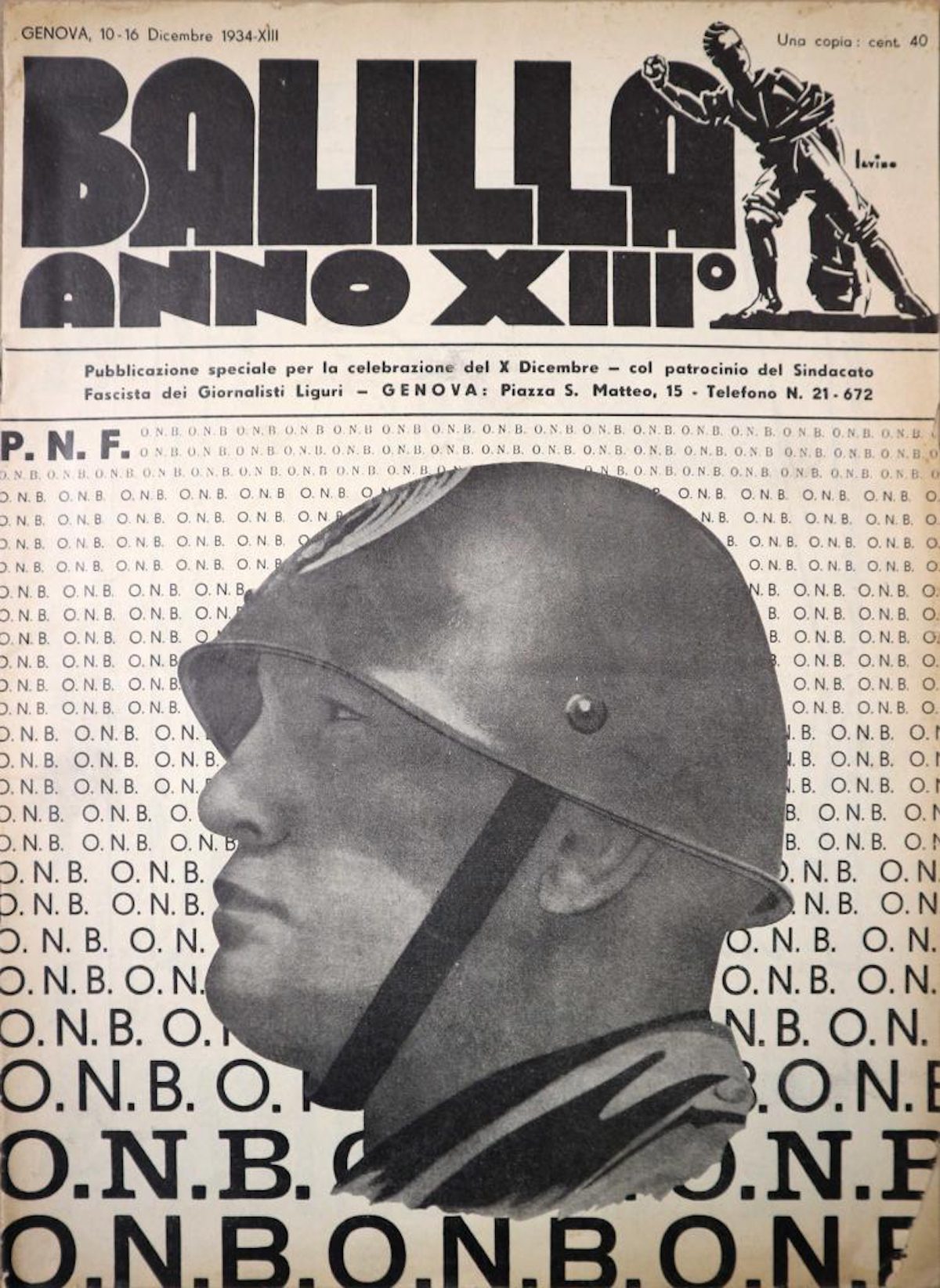

When Lippmann published those words, Mussolini was busy founding the Fasci de Combattimento. He lost the 1919 elections, but the man who would shape himself into the larger-than-life Il Duce did manage to enter the Italian parliament in 1921 and, with the complicity of liberal ministers, institute strict censorship and absolute control over the press. As Mussolini consolidated his dictatorship, “most of his time was spent on propaganda, whether at home or abroad,” one history explains, “and here his training as a journalist was invaluable. Press, radio, education, films—all were carefully supervised to manufacture the illusion that fascism was the doctrine of the 20th century that was replacing liberalism and democracy.”

To aid in the effort, Mussolini enlisted Futurist artists, many already fully on board with the fascist program, and communications experts already immersed in swaying what Lippmann broadly called “public opinion.” A current exhibit of Italian Fascist propaganda at New York University introduces the many examples on display by noting:

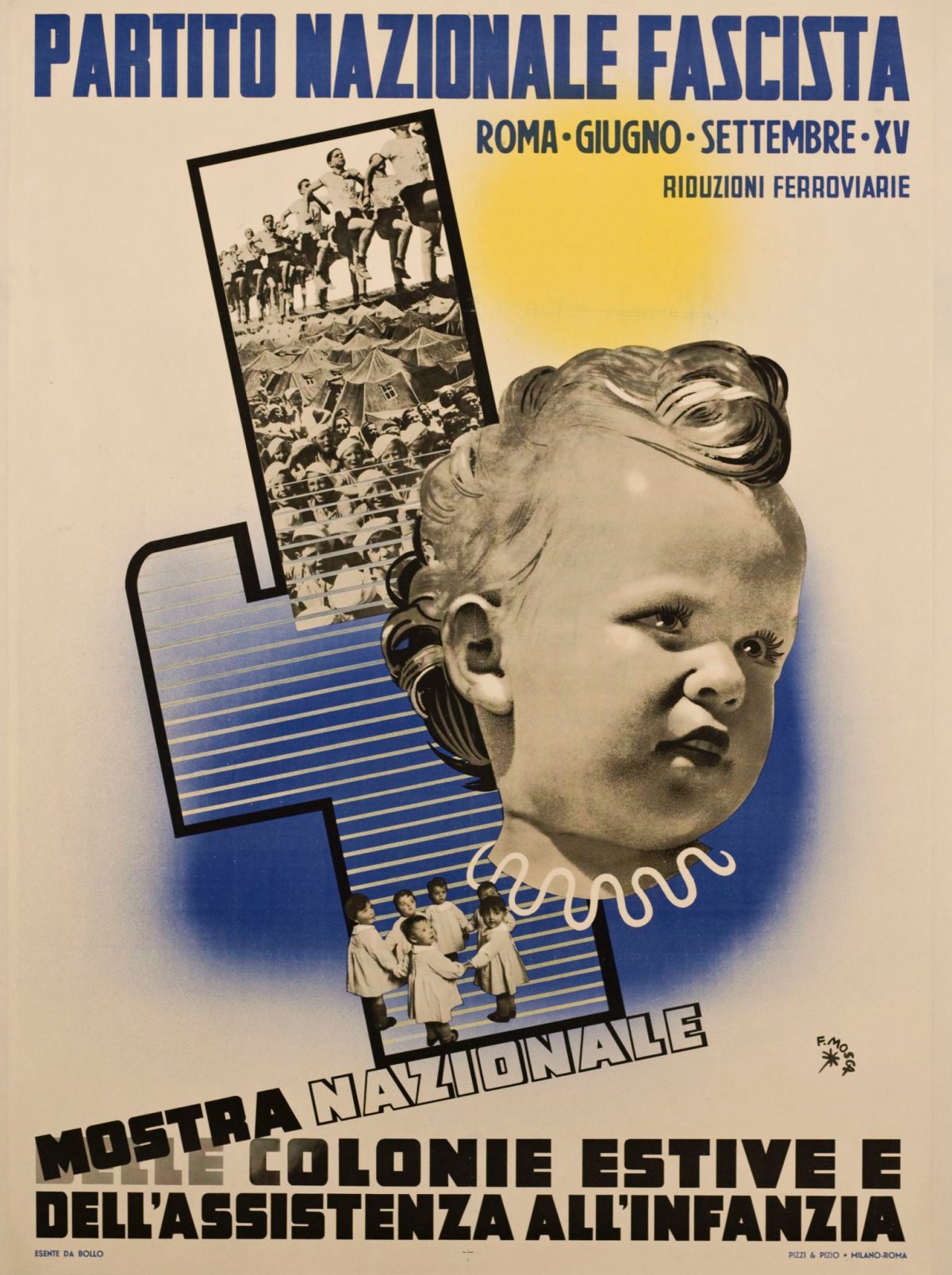

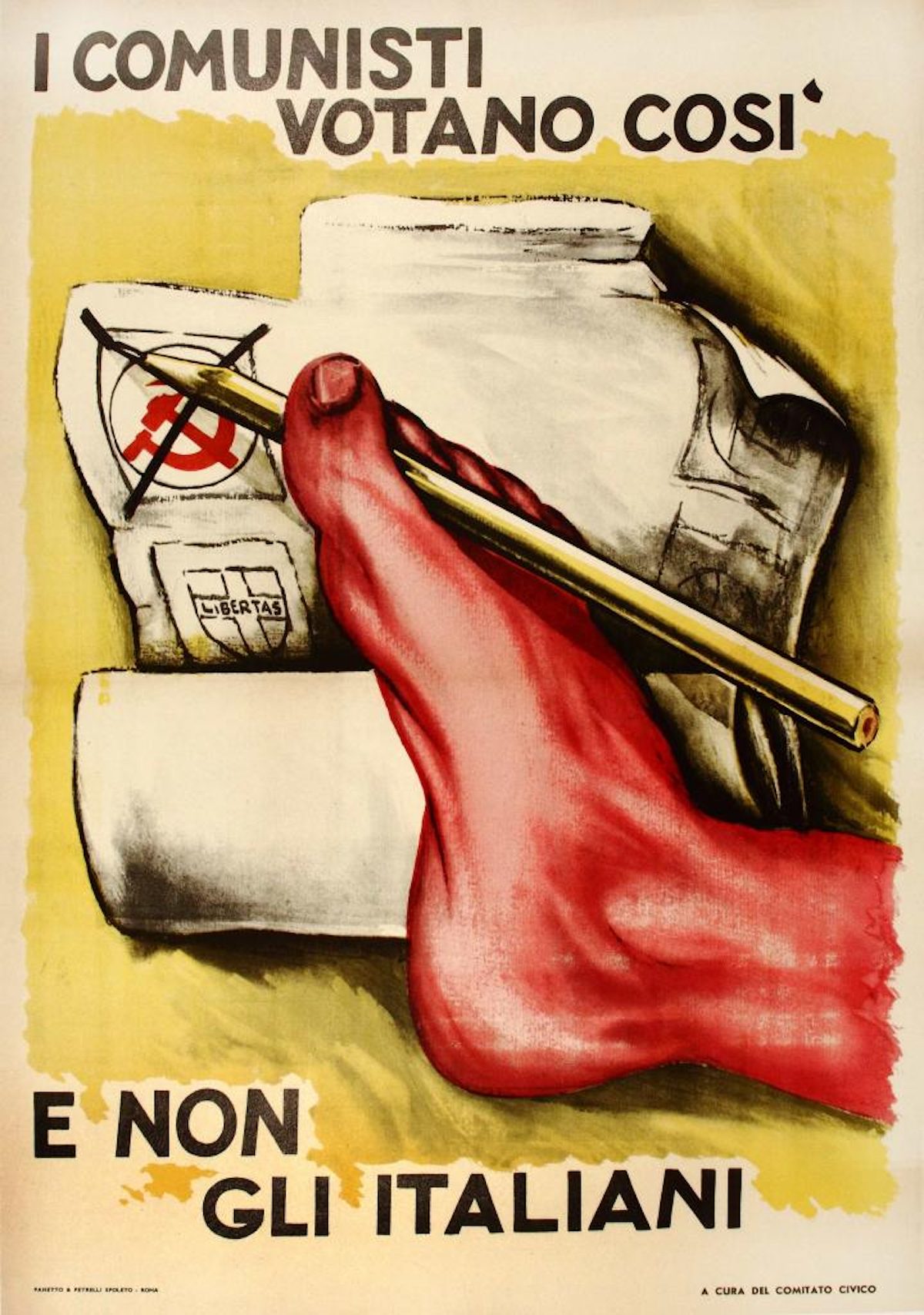

[F]ascist political propaganda coopted modernist aesthetics, mass communication, marketing techniques, and popular culture to manipulate society and muster support for its totalitarian endeavors. Considered together, the propaganda emerging from fascism, as well as from the particularly tense democratic times surrounding the fascist period, provide an opportunity to deconstruct the rhetoric of political communication in its entirety, and represent a call to engage critically with the multitude of competing political narratives that surround us today.

Communicating strength, health, authority, control, and the Neoclassical ideals in which Mussolini’s fascist state wrapped itself, the posters and publications from 1922 to 1943 show how fascism was normalized and made a part of everyday life. But Italian fascist propaganda is unique in that it embraced modernism, where Nazism rejected it wholesale and persecuted its “degenerate” artists.

Italian fascists realized, exhibition curator Niccola Lucchi tells Print, “that, as long as the propaganda message remained consistent, welcoming a variety of different modernist languages would project the idea that the regime welcomed creativity”—and, therefore, independent thought. “Fascist Italy co-opted every artistic current—an entire generation of artists gravitated in the orbit of the regime, which turned them into accomplices through misleading promises of artistic freedom.” The uneasy marriage of totalitarianism and creative liberty proved a particularly effective for Mussolini as a means of neutering subversive aesthetic movements by putting them on the payroll.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.