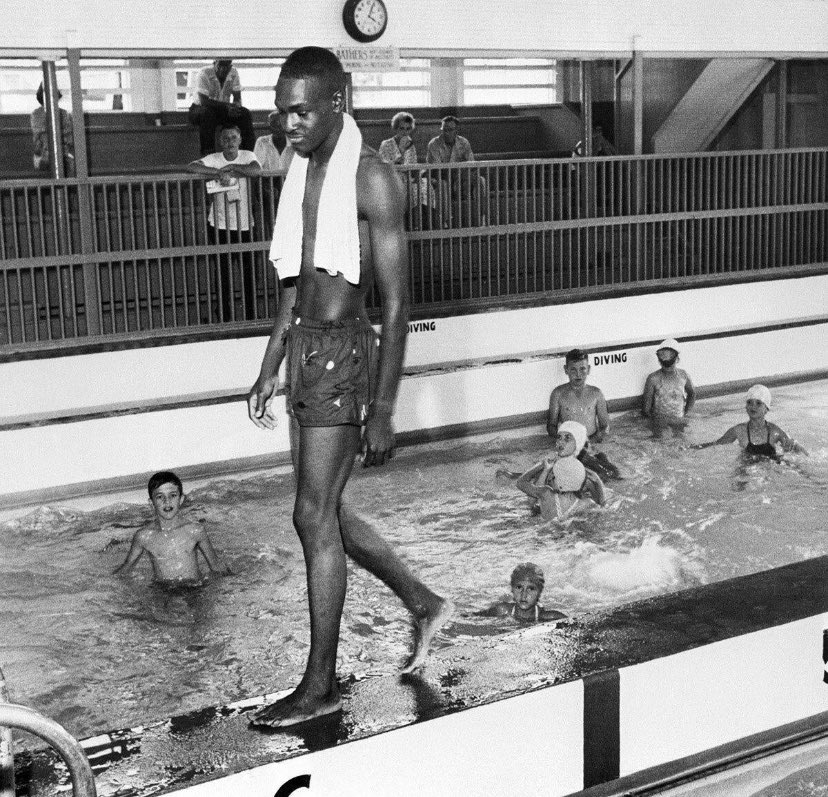

On 8 June 1958, 19-year-old David Isom (above) swam at Florida’s Spa pool. Isom said he was treated like “any other citizen” by the woman who’d sold him his entry ticket and the 45 people already in the water. Tommy Chinnis, the lifeguard on duty, said Isom “was like everyone else”. He was. But in the eyes of the law, he wasn’t. David Isom was the only black face in the segregated pool for whites only.

The local paper reported at the time:

“David Isom, 19, broke the color line in one of this city’s segregated public pools this afternoon which resulted in officials closing the facility. This is the second such incident within the past 72 hours. Two white swimming areas now have been closed due to attempts of blacks to use them.”

Isom, a graduate of Gibbs High School, said: “I feel that it’s not a privilege, just a right.”

John Gough, the venue’s manager, immediately cleared the pool and closed the place. Gough claimed he’d been instructed to do so by city manager Ross Wisdom, because “a negro had used the facilities”.

The pool was drained and rid of all traces of black swimmer. It was then refilled with water, chlorine and spite, and the racially superior invited to step Nazi-like toward their literal gene pool, and try not to drown in the manner of a butterfly, crawler or paddling dog in the pursuit of better health.

What went for Isom went too for black Jewish entertainer Sammy Davis Jr., who took a dip in a whites-only swimming pool at the New Frontier in Las Vegas. Afterward, that manager also drained and cleaned the pool.

There were stories of white swimmers spiking the water with nails at a pool in Cincinnati and pouring bleach and acid in pools in St. Augustine, Florida, more of which later. There had been riots at pools in Baltimore, Los Angeles, St. Louis and Washington DC.

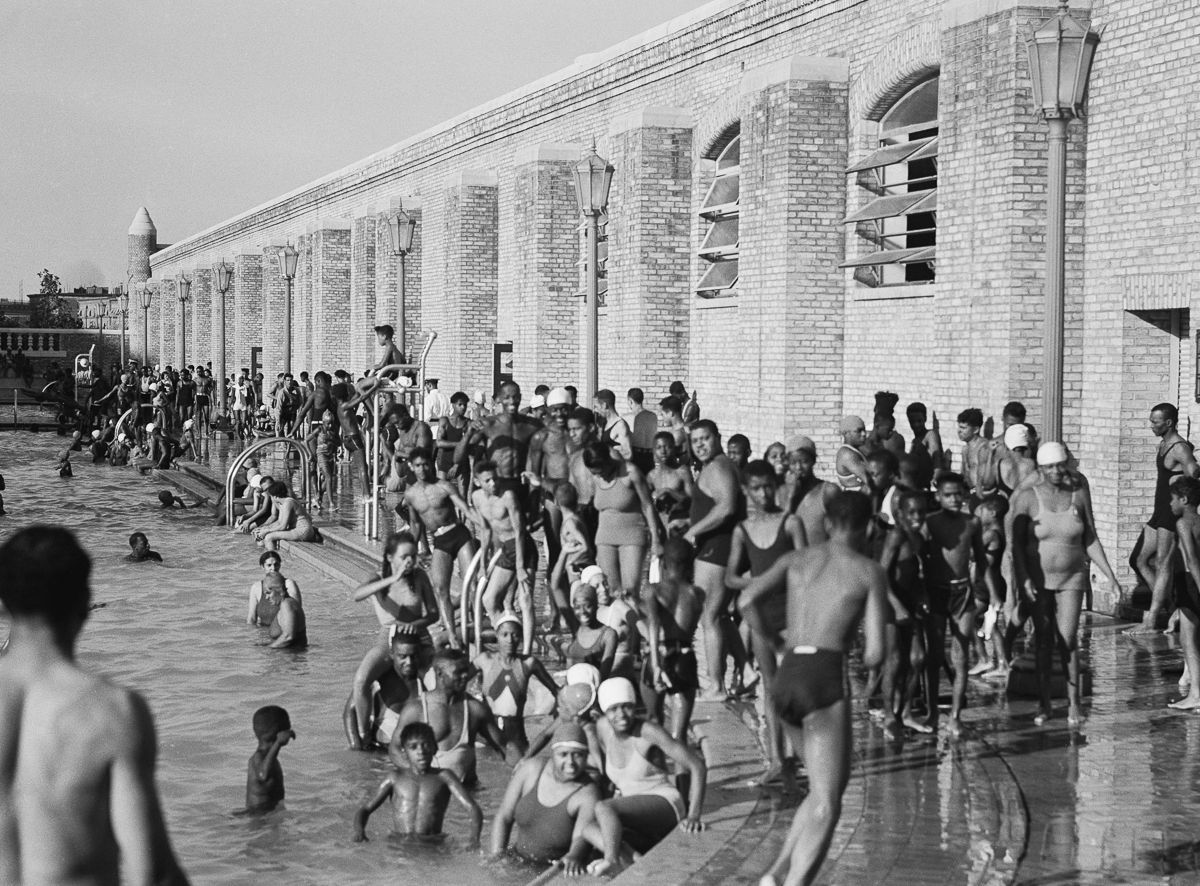

Black swimmers enter Fairgrounds Park Pool in St. Louis in 1949. They were the first black swimmers to enter the pool, and they were assaulted by angry white residents soon after the photo was taken. The Fairground Park Pool, when it was built in 1912, was the largest municipal pool in the world, and it was only open to white people until 1949. – St. Louis Globe-Democrat Archives – University of Missouri

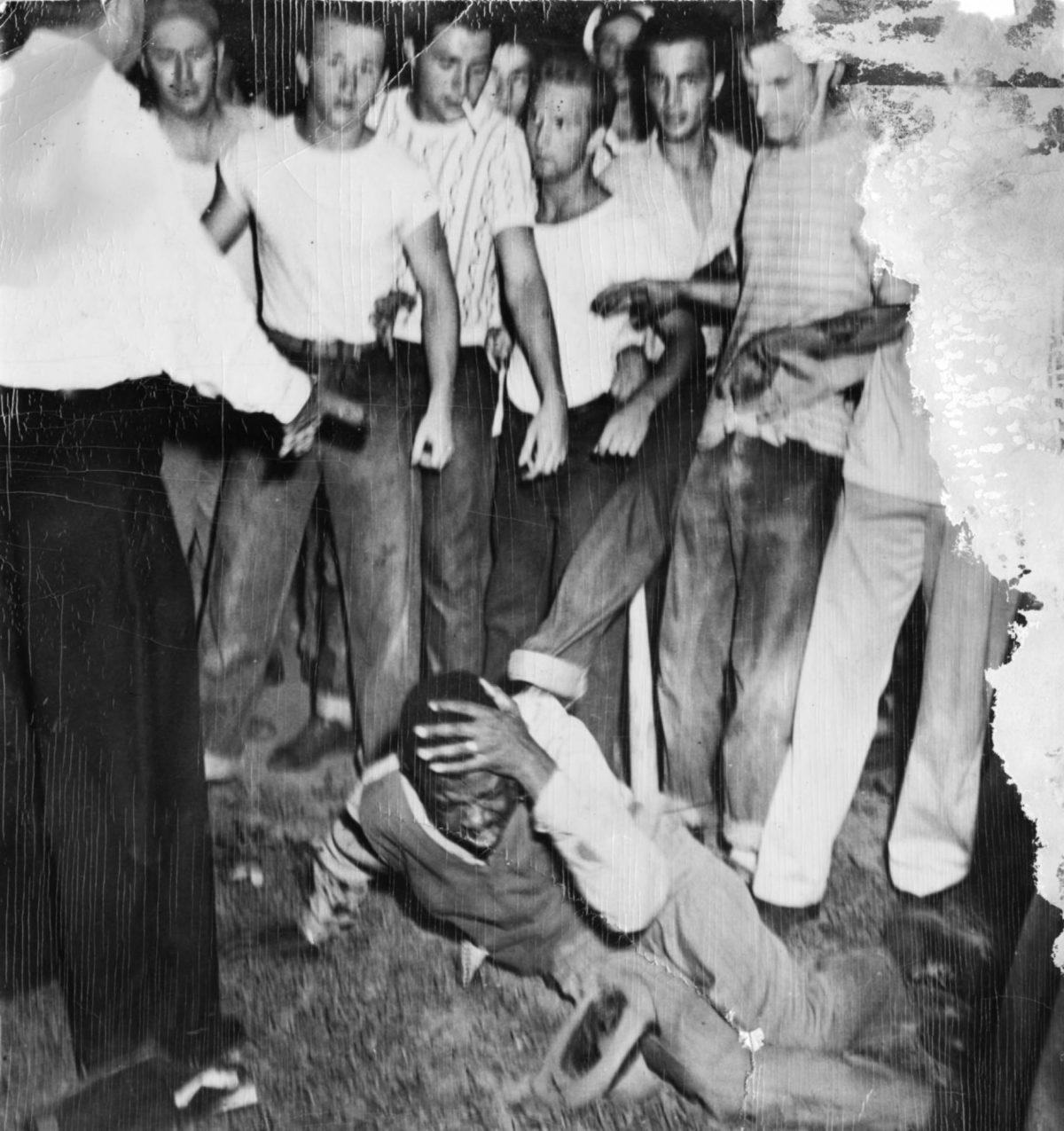

Race riot at the Fairgrounds swimming pool, St. Louis, Missouri, June 21, 1949. Text on reverse: “News release: NEGRO SWIMMING PERMISSION INCITES RIOT…. St. Louis, Mo. A group of white youths shown crowding around a negro who already has been attacked. Two feet are shown extended as if to kick the negro to the ground. A baseball bat belonging to one of the youths is also visible.”

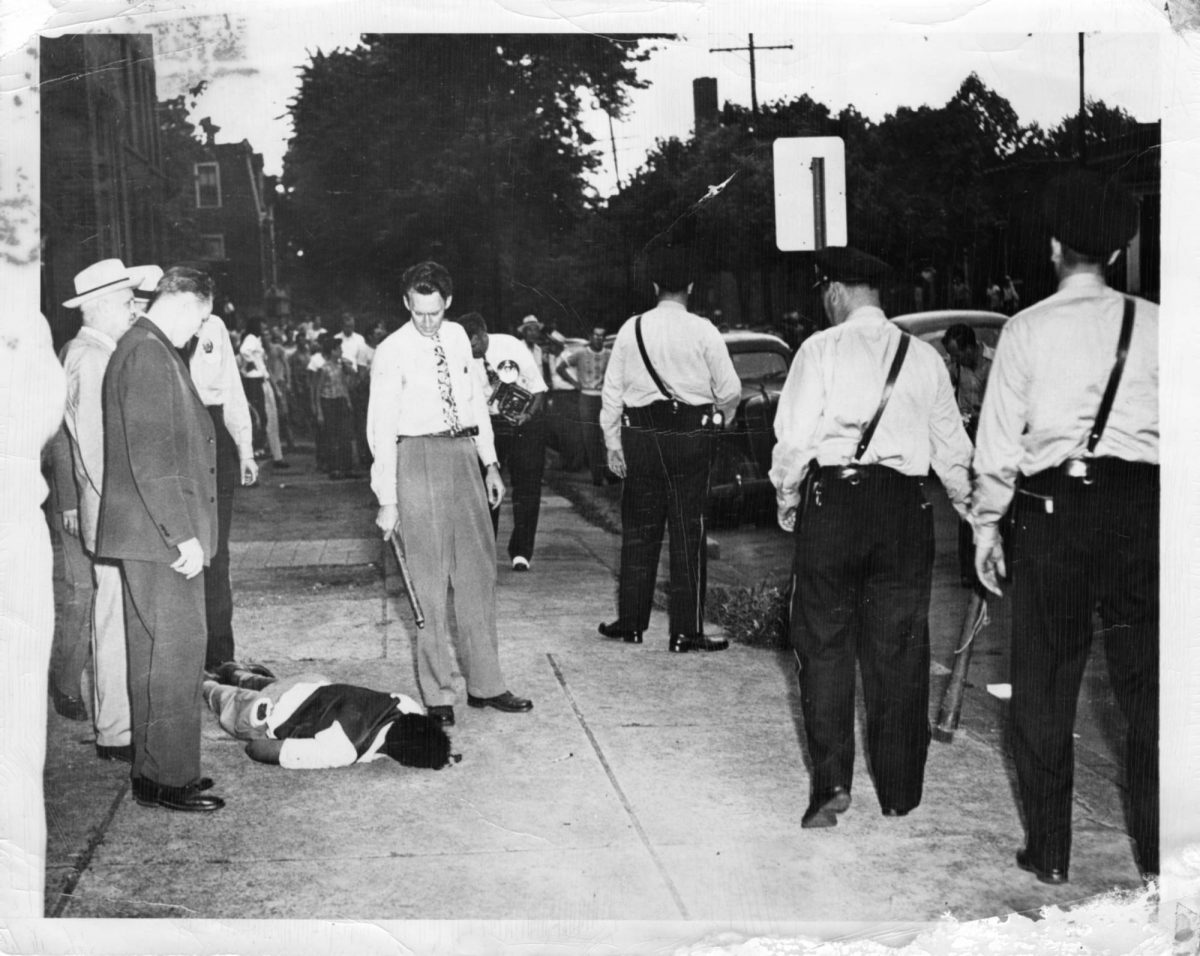

Aftermath of a race riot at public swimming pool, St. Louis, Missouri, June 21, 1949. Text on reverse: “Race riots greet swimming pool order… St. Louis, Mo… An unidentified negro victim of the racial disturbance in St. Louis Tuesday lies on the ground unconscious as police surround him to keep away the crowd. He was one of the swimmers in fairground park pool, center of the disturbance. Towel and swimming trunks are visible in his pocket.” – Georgia State University

And if swimming didn’t get you beaten, there was the crime of FWB (floating whilst black).

The 1919 Chicago race riot, which lasted seven days and claimed 38 lives, began on the shores of Lake Michigan, when white youths stoned to death black teenager Eugene Williams after the non-swimmer had accidentally floated on a raft across an invisible colour line in the water. The first police officer at the scene refused to take the killers into custody. In its aftermath, African Americans learned to avoid the city’s lakefront.

Black Chicagoan Dempsey Travis remembered: “I was never permitted to learn to swim. For six years, we lived within two blocks of the lake, but that did not change [my parents’] attitude. To Dad and Mama, the blue lake always had a tinge of red from the blood of that young black boy.”

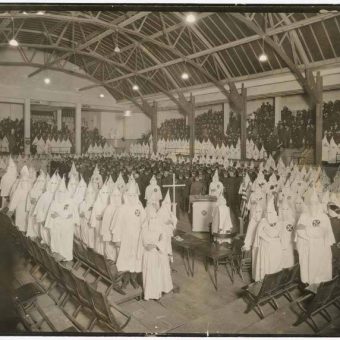

This image shows Klan members, covered in robes and hoods, during an event at Crystal Pool, a public natatorium in Seattle – 23 March 1923

There were plenty of pools. After the Great Depression, the Public Works Administration and the Works Progress Administration funded the construction of around 1,000 swimming pools nationwide. It was backed by the national “learn-to-swim” campaign. But many of the pools were racially segregated. Skin colour was no barrier when it came to paying taxes to build the pools, but using them was a white thing.

In cities, black citizens were allowed to use only older pools. Whites in Louisville, KY, had four new pools to swim in. Blacks could only bathe in Sheppard Pool, constructed in 1924. Until its existence, all the city’s swimming pools were off limits to all African Americans.

A March 24, 1923, editorial entry from the Louisville Leader, a black newspaper, chronicled this feeling prior to Sheppard Pool’s construction at 17th and Magazine Street:

“The swimming pool that is about to be erected for Colored people is one of the things that is a necessity to the life of the boy and girl, and grown folks too for that matter, whether white or black. As a recreational institution the swimming pool is the greatest to the health and happiness of the youth of today.”

But when pools were desegregated, things was hunky-dory thereafter, right? No, of course not. As Yoni Appelbaum writes, the popularity of private pools and members-only pool clubs and country clubs boomed in the postwar years:

“Before 1950, Americans went swimming as often as they went to the movies, but they did so in public pools. There were relatively few club pools, and private pools were markers of extraordinary wealth. Over the next half-century, though, the number of private in-ground pools increased from roughly 2,500 to more than four million. The declining cost of pool construction, improved technology, and suburbanization all played important roles. But then, so did desegregation.”

Appelbaum says that in Marshall, Texas, 95 percent of residents voted in 1957 to have the city sell off its recreational facilities. And the local pool’s new private owners reopened it as a whites-only space, for whites-only snot and whites-only athlete’s foot.

In Jackson, Mississippi, black and white citizens could not swim together in the capital city’s taxpayer-funded swimming pools. In 1961, a group of black Jacksonians began demanding that pools there be integrated. In 1963, Mayor Allen C. Thompson closed four public pools in 1963 rather than integrating them. The City sold the fifth to the YMCA, which continued to operate it as a whites-only pool.

And then came another incident caught on camera. On 2 July 1964 the Civil Rights Act guaranteed equality among all people in the United States. On the cusp of that momentous achievement, Martin Luther King Junior was at the Monson Motor Lodge Motel in Saint Augustine, Florida, intending to eat at the restaurant. The Motel’s owner, one Jimmy Brock, blocked him. King was arrested for trespass. From jail he wrote to his friend Rabbi Israel S.Dresner requesting a demonstration to get the story into the news. On June 18, the march was arranged.

During the protest some black activists and two rabbis (17 rabbis had already been arrested) arrived at the Monson and felt the need to cool off in the pool, which, like the food, was reserved only for whites. They jumped in. Photographer Horace Cort snapped Brock pouring muriatic acid into the water to force the swimmers out and “clean the pool”, which he later drained in an act of ‘purification’.

J.T. Johnson and Al Lingo, two of those protesters who were at the Motel, recalled the event in 2014:

JT: “Everybody was kind of caught off guard.”

Al: “The girls, they were most frightened, and we moved to the center of the pool.”

JT: “I tried to calm the gang down. I knew that there was too much water for that acid to do anything. When they drug us out in bathing suits and they carried us out to the jail, they wouldn’t feed me because they said I didn’t have on any clothes. I said, ‘Well, that’s the way you locked me up!'”

The effect of so much violence was deadly. At the exhibition ‘POOL: A Social History of Segregation’, we learn:

For many Black individuals and families, the answer to these growing disparities has been to avoid the water altogether or to stay in the shallow end or to pretend to be able to swim when forced into the water.

But this is just the beginning of the story, really. Past racial discrimination at swimming pools, coupled with a general shift of funds away from public pools to private swimming and recreational opportunities, have had a significant and lasting impact on black communities — an impact that continues today:

According to reports from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Black children and teenagers are almost 6 times as likely as white children to drown in a swimming pool. USA Swimming reports that 69% of black children have little to no swimming ability, compared with 42% of white children.

And you wonder what kind of world we live in that wants some kids to be left behind.

The Kosciusko Public Swimming Pool in the Heart of the Bedford-Stuyvesant District of Brooklyn in New York City. People Here Enjoy Themselves at the Intelligently Located Pool. By Danny Lyon

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.