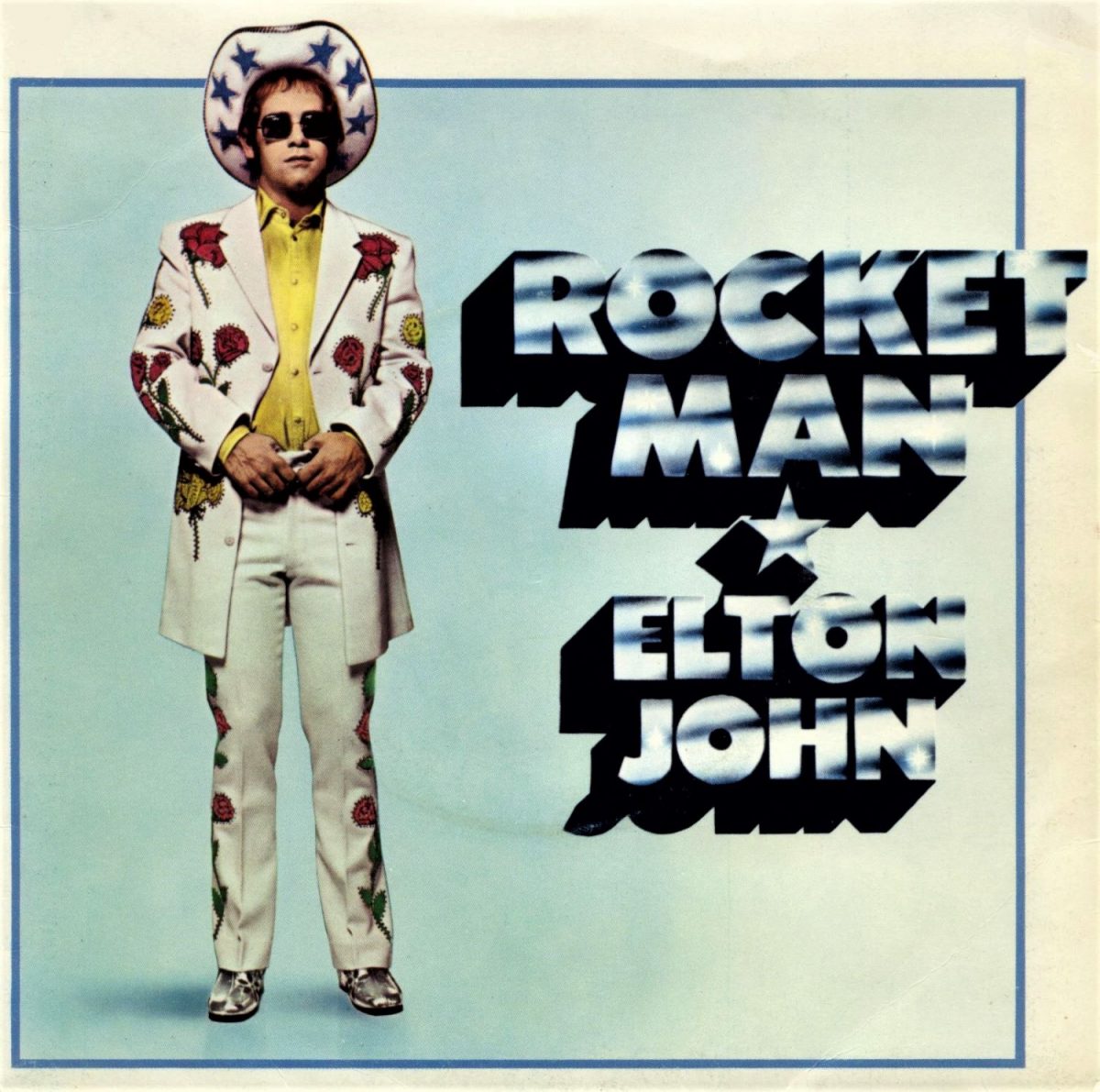

Elton John wasn’t just a ‘Rocket Man’ he could travel into his past lives as a musician and a soldier and bus driver.

Elton John didn’t want to know about any past lives. He was sure “this was his first and last time here”. But a friend, the tennis player Billie Jean King, encouraged him to give it a try. Who knew what he might discover?

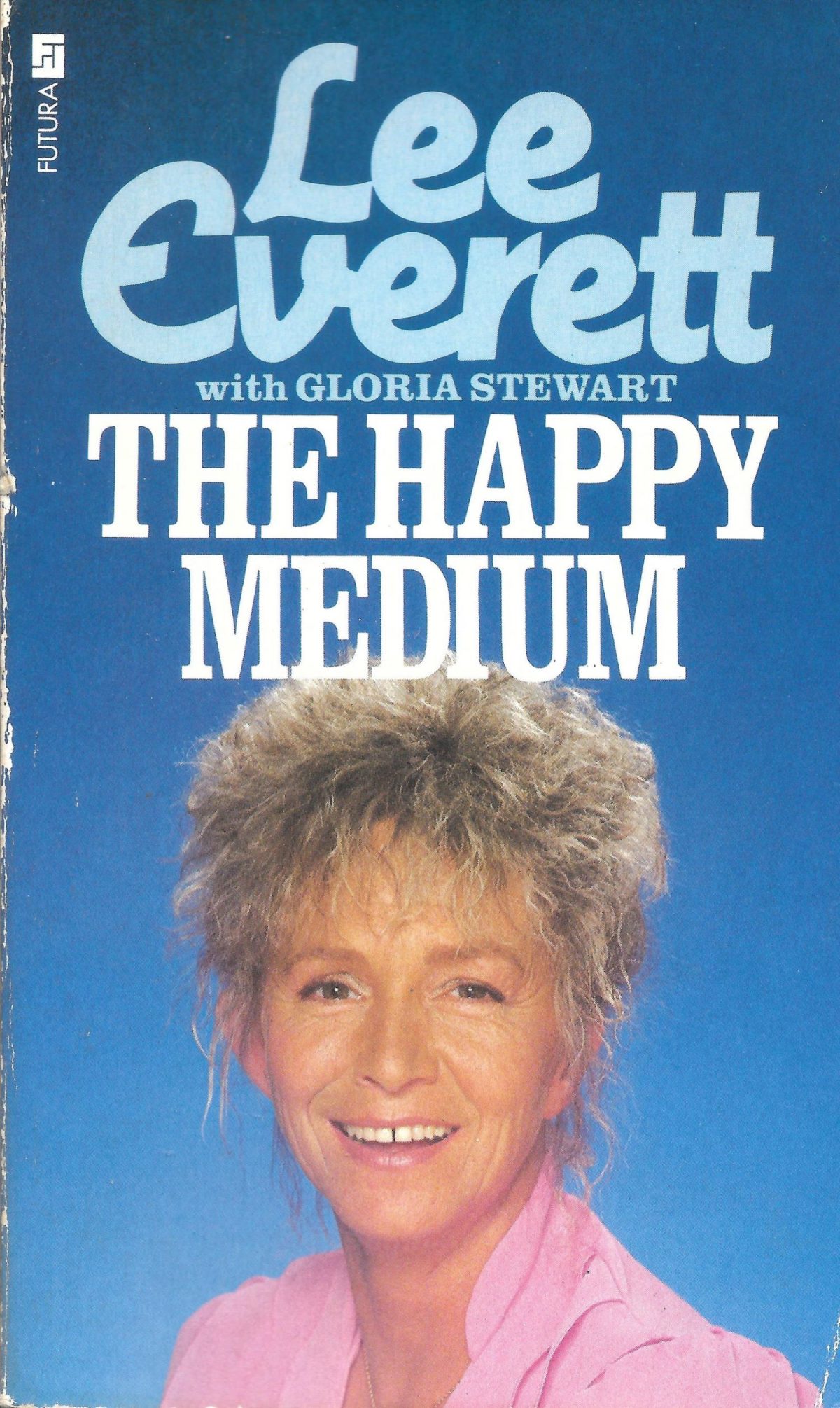

John visited Lee Everett Alkin, a medium, healer and an expert in Regressional Therapy. After the hellos and ‘how-are-yous?’ and ‘tea or coffee?’ Everett Alkin asked John to sit down, relax, close his eyes and picture a door. It takes around ten minutes for someone to regress. Sometimes longer. John saw himself being greeted in a dark, sombre hallway by a small shaggy dog. Then John saw where he was:

‘It’s a dark stone house. The stone is very old, the place is cold and dreary. I don’t like it here at all.’

Everett Alkin asked John to look around the rooms.

‘The dining room has a long wooden table, a fireplace, and the walls are all stone. The room is very large and there are two or three people in the room. I can’t make them out very well but they’re wearing very old clothes, velvets, it looks like pre-Elizabethan. The woman is wearing a long dress. It’s not a poor house, it’s very big but there are no ornaments of any kind.

‘I’m now sitting in the centre, at the side of the dining table. There’s a man at the head of the table–I think he’s my father–and another man on my left and the woman is sitting opposite me and I feel she’s my mother. We are being served food by two women wearing aprons.

‘I can’t see the stairs but I’m now in the upper part of the house in a small bedroom with a fireplace and window, again very bare. There’s a bed and a table with a candle on it. I’m wearing long, skin boots on my small feet, and a long shirt. I’m a boy of about eight years old. It’s a cold lonely life, and I die very young, there are no more memories past this point.’

Everett Alkin took John away from this memory. She hoped John might remember a second life. She was not disappointed. John said he was now standing in a garden looking at a beautiful French château surrounded by fields:

‘It’s my house. I enter through a magnificent wooden door with gold trim. It’s an ornate house with gold leaf all over the place. I take hold of the door handle with a gloved hand. I’m a twenty-eight year old man, very finely dressed, rather like a cavalier, with long curly hair, a large hat and belt with buckle and sword. The house is lavish and crammed full of beautiful things. There are paintings of family: my mother and father and a separate one of me. The hallway is light, very light, it’s full of beauty and I’m obviously wealthy. The gardens are laid out in symmetrical detail. I’s a typical French château.’

Audrey Valentine Middleton wasn’t like the other children in her class. When some of the children talked about what they would like to be when they grew up, Audrey talked about who she had been in her past lives. Audrey knew everyone was reincarnated. Audrey knew her present life was only one of the many she had lived and the many she would have to live until she became part of something greater. Her friends laughed at her and teased her. Audrey stopped talking about her past lives–even though she knew those past lives had been real.

Middleton kept quiet about her secret knowledge. As she grew up, Middleton was encouraged to become a singer. In 1958, the 21-year-old moved to London. She performed in clubs and quickly signed-up as a backing singer to Emil Ford.

Ford was best-known for number one hit “What Do You Want to Make Those Eyes at Me For?” in 1959. Ford had synaesthesia. Music or certain types of music made Ford see colours. He claimed it helped him produce the very best recordings.

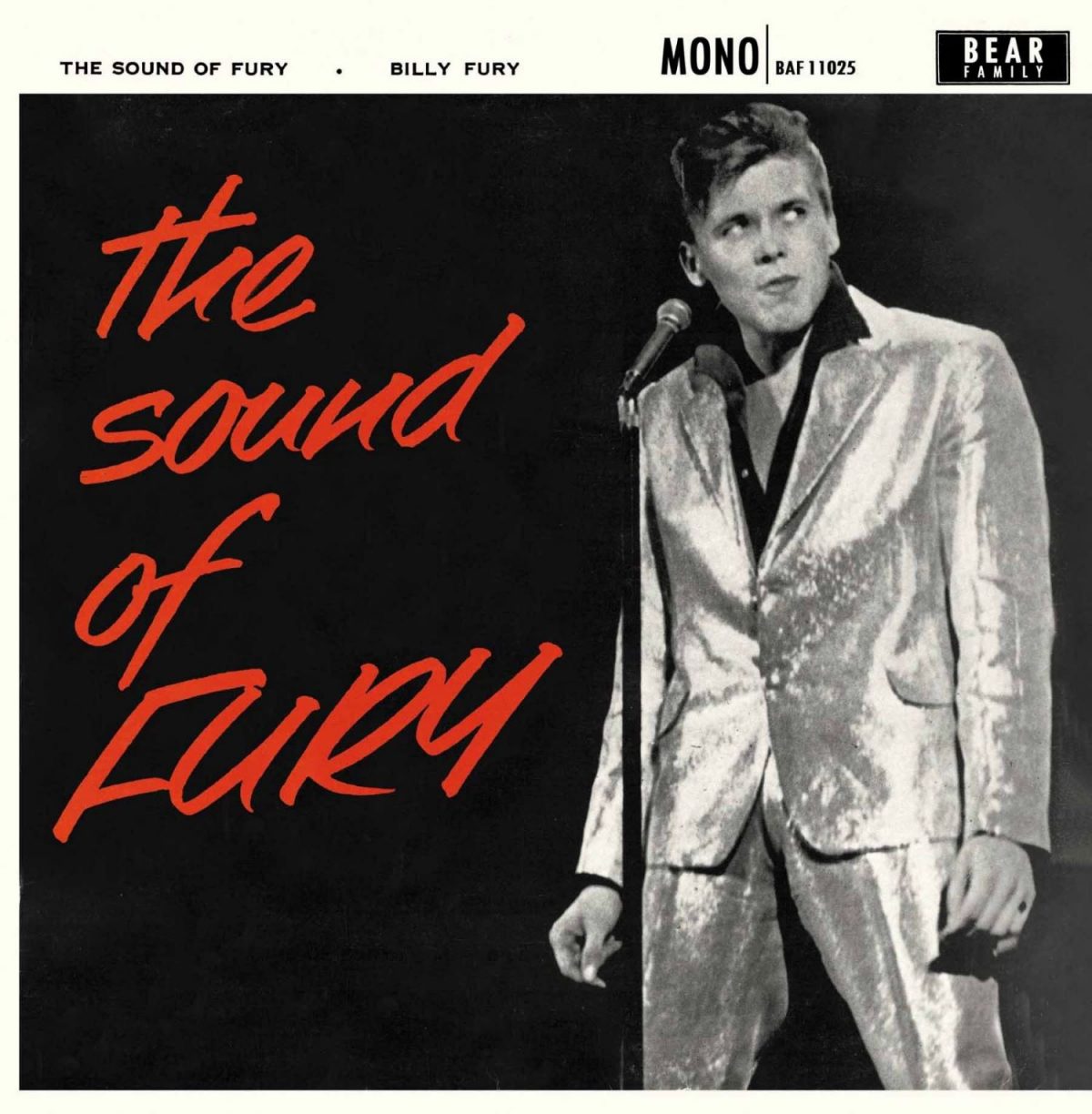

Middleton had a good voice and stage presence. The agent Larry Parnes signed her up to his roster of artists, which included Tommy Steele, Marty Wilde, and Billy Fury. Parnes renamed Middleton Lady Lee. She started touring the UK. She also started a relationship with Billy Fury, who was on the cusp of becoming Britain’s greatest rock ‘n’ roll star with the release of The Sound of Fury in 1960.

Billy Fury’s ‘The Sound of Fury’ is considered ‘the best rock & roll album to come out of England’s original beat boom of the late 1950s’.

Lee recorded a series of singles, including “I’m into Something Good” in 1964 which became a hit for Herman’s Hermits. But Lee’s career did not take off. Her singles flopped and a new “Mersey Beat sound” which was reshaping the landscape. Lee and Fury split in 1967. Not long after, Lee met and married DJ Kenny Everett in 1969.

The relationship with Everett was fun but full of ups-and-downs as he was conflicted by his homosexuality. Kenny fell in love with an engineer at the BBC, who was heterosexual and not interested in Everett. It caused the DJ further turmoil. As the couple worked out their relationship and Everett’s sexuality, Lee found her spiritual, clairvoyant abilities growing. She had flashbacks to her previous life. One where she was a nun tortured by members of the Spanish Inquisition. Lee understood how these past lives influenced her present existence. As Lee wrote in her book Celebrity Regressions:

The more I look back at what happened with Kenny, the more I think that we all perhaps volunteer to come to each other’s lives at certain points just to assist in one particular way, a way that perhaps has been successful before. From where I’m viewing life, who’s to say we don’t all gather at the beginning of a loved one’s incarnation to work out how we can all appear and help!

Elton John was still in regression. Lee Everett-Alkin asked John to describe where he was in this château:

‘There’s a long dining table, (not nearly as long as the first one I saw, though). It seats about sixteen people on gold chairs. I can’t see anyone else, I seem to be eating alone. I’m being served by a young footman who brings me wine and a bird, a game bird.

‘Now I’m sitting in a beautiful, beautiful room with a piano. I’m alone and sitting at the piano playing. I’m not writing or reading music; I know it’s my own composition.

‘I socialise a lot in Paris. I see myself eating a meal in a restaurant. There are six people including myself, all wearing similar clothing, late eighteenth century, fine and ornate, and we are all wearing wigs. We are just six men at the table, no ladies, talking and laughing and being very loud.

‘I’m now seeing myself in my early forties. I’m in Venice and I know I’m very ill. I’m looking out across the bay to the other side of Venice and I know I’m gravely ill. This is the hour before my death. There’s a priest by my bed.’

Just as one past life finished, another revealed itself to Elton John. This time all he could see was mud. He was a soldier in khaki wearing a tin hat, all covered in mud. John was a soldier in the trenches during the First World War. The memory shifted:

‘We’re marching along a road and I’m absolutely exhausted. We get to a bombed out house and we all flop down inside to rest. It’s France.’

John’s memory moved on a year:

‘I’m in hospital. I’ve been injured, there’s shrapnel in my leg and I’m here to have it taken out. My wife’s at the bedside. She’s a small, dark-haired woman, she’s only about twenty-three. The war is over for me now.’

This life now concertinaed towards the end:

‘I’m a bus driver in London. It seems to be the early forties. I’m living in the same small, terraced house that I was born and brought up in. The wife and I live with my parents, we have no children.’

…..

‘I’m aged forty now. I’m driving the bus. I’ve lost control and it crashes. Everything’s gone dark.’

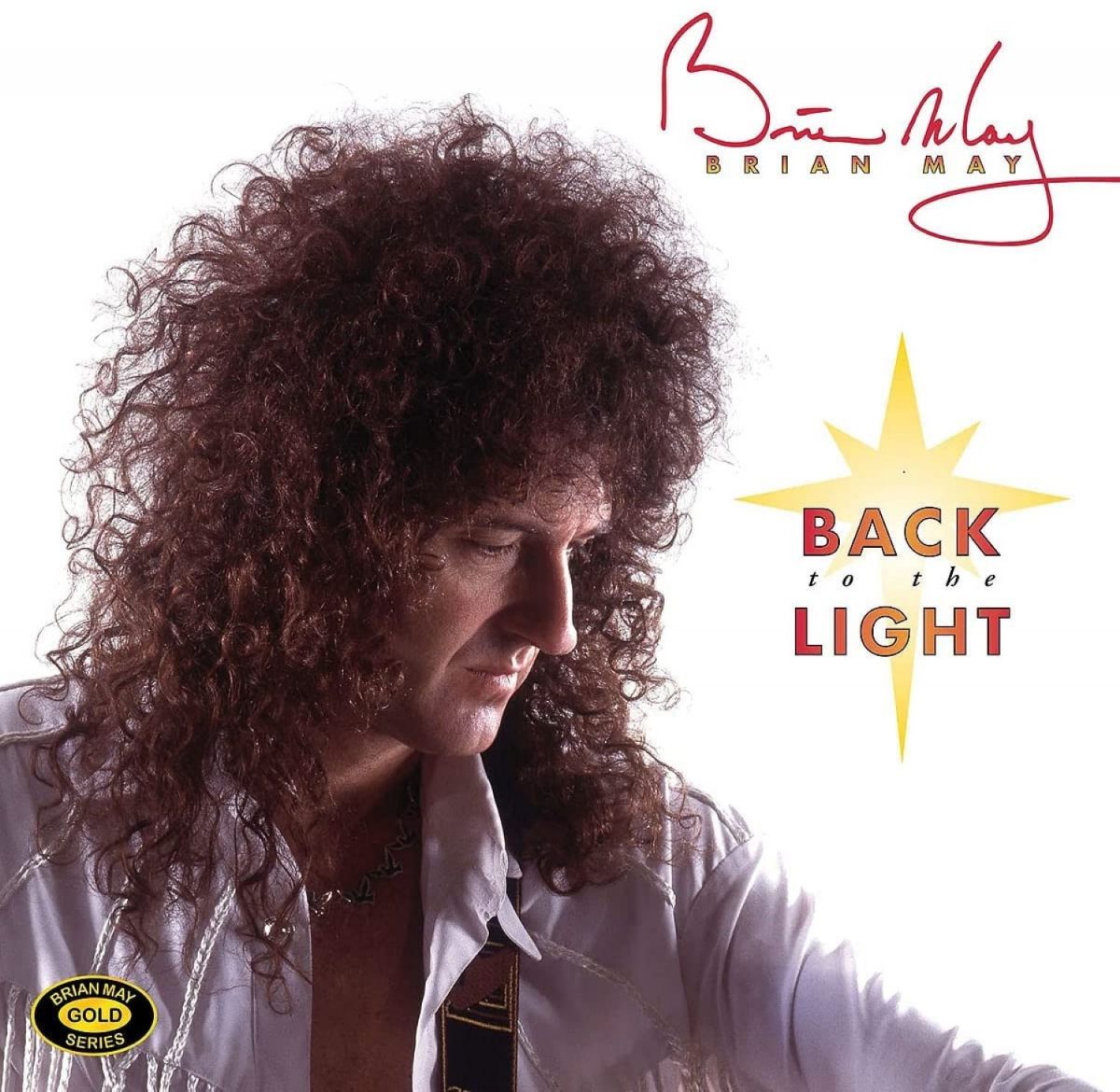

Another musician Everett regressed was Queen‘s guitarist Brian May. Everett had originally asked Freddie Mercury, who agreed one drunken night. The following morning Mercury reneged claiming he was too scared to find out who he was in a past life. May had no such issues. Everett met May in Queen’s office in Holland Park. Among the sounds of traffic, phones, and people talking, Everett regressed May.

‘I’m seeing a very light reddish coloured wooden door with two large panels at the top and two smaller below. As I reach out my hand to open the door I see that it’s a bit more hairy than my present hand. I’m wearing a tweedy jacket and brown trousers with black, shiny, pointed shoes. Inside the room there are pictures on the wall with gilt frames, mostly landscapes. It’s a big sitting room with sofas and lots of people all standing around drinking cocktails. There are all dressed quite smartly, smarter than I am. I think I’m just visiting. I realise now it’s a funeral I am attending.

‘I live in an end of terrace house in the early twentieth century. The dining room has quite a big table. There’s a lady sitting there with slightly greying hair, a gentle lady. I’m quite old: I feel she’s my wife. There’s just her and me now–it feels like everyone else has gone.’

Queen: Roger Taylor, John Deacon, Freddie Mercury, and Brian May.

Everett-Alkin stopped May‘s description and took him back to when he was just fifteen years old.

‘I live in a big house and my parents are quite jolly-looking. Dad’s wearing a brown suit with a fob watch. It feels like 1860. I think my dad is a photographer. My first job is working outside on a farm, where there are pigs and cows. I don’t like it very much. I feel like I want to get away.

‘By the time I’m twenty I’m an apprenticed to what seems like solicitor–I’m learning a trade.

‘I get married at what looks like Clapham Common: it’s a church on a big green. I can’t see the wife….

‘….I can see her now: she’s very beautiful. She’s very young, about eighteen, but very beautiful with a straight nose. Our first married home seems to be the terraced house I first saw.

‘By the time I’m thirty we have three children. I’m still at the same job in the city at the same office. I think I’m a solicitor or something.’

The story moved to fifty years old.

‘I’m in the small house in the study, sitting behind a desk. I’ve received a piece of paper that tells me what’s happening. Someone has died and they are a long way away, in India or somewhere. I don’t know who it is because I can’t feel anything. It feels like it’s professionally important. A year later we are living in the big house; we moved into it after the death of my business partner. It feels big and empty and I don’t feel I’ve enough furniture to fill it. I feel we didn’t want to move out of our lovely terraced house.’

Everett-Alkin returned to the funeral. Whose funeral was it?

‘I realise now it’s my own. I’m seeing it all, looking at the guests, it’s very strange.’

When Everett-Alkin closed that life story, she attempted to unlock another past life. But May kept returning to the same one. She believed May still had something to work out. May commented at how sad he had been at his funeral. Not because he had died, but because he was leaving his wife.

When May returned to the light he saw his wife looking the same age as when he died. May went quiet. Everett-Alkin asked what was wrong?

‘It’s Anita [Dobson], she now looks like Anita.’

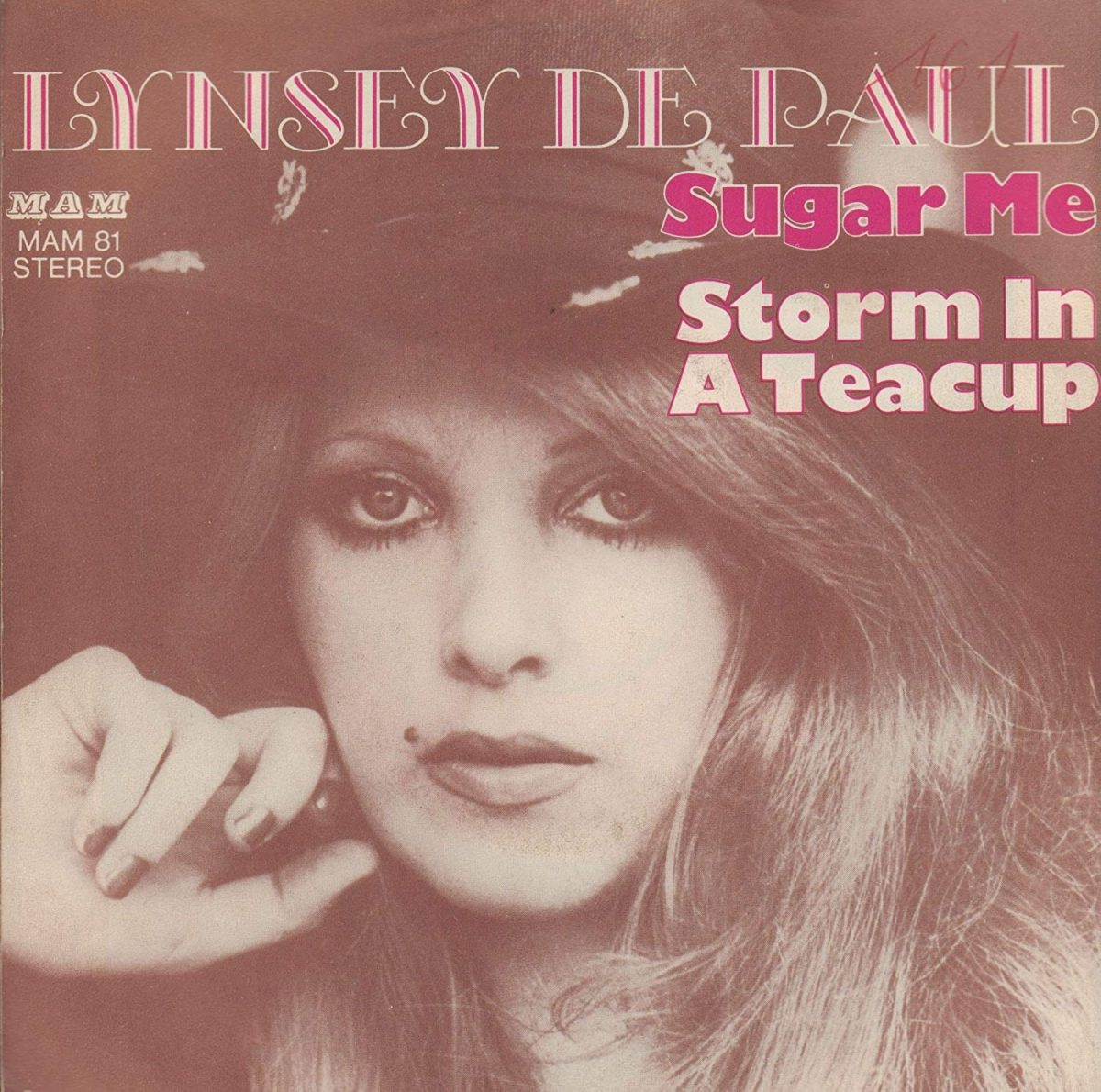

The first time Everett-Alkin regressed the singer and song-writer Lynsey De Paul, nothing happened. On the second and third occasions, De Paul revealed a long connection with music and piano-playing which she thought explained her career as a musician.

‘I can see a girl–it could be me. I think it’s the fifteenth century. She’s got her hair pulled back and her whole head, apart from the front of her hair is under this little, white cotton bonnet thing; it’s not a hat. It covers the back of the head and then there’s a stiff frill of cotton. I think she’s a servant in a house. She’s wearing a white apron over a dark maroon skirt with petticoats under a little dark top. It’s all very plain, she’s definitely not someone of any standing. She’s between seventeen and twenty. The house is not huge, it’s not the Duke of Westminster-type place, but it’s a good home and belongs to someone of some standing in the community.

‘She was about thirteen when she first came to work at this house. She had been brought up locally, without education, by hard-working folk. The father had some sort of trade but I don’t know exactly what, and the mother did odd jobs to help out but didn’t really work apart from coping with the home and children. She was sent off early into service because they didn’t want to pay for her keep. She was sent off as soon as she was old enough to earn her own living.

‘She sleeps in an extremely bare room that has a fireplace. There are small, leaded windows, plain bed and plain floorboards, very grey altogether. She’s not unhappy; she doesn’t even think of it. She cleans out fireplaces and does all the menial jobs, and eats her meals with the rest of the staff in a kitchen room. She doesn’t question anything, she just accepts it all, glad to be clothed and fed and looked after. She’s not stupid, just naive and simple because she stays in the same position and works hard, she gains more trust as the years go by. She never goes out socially but is quite content. By the time she’s in her forties, she is running part of the kitchen–that’s her life. At fifty she has become frail and can’t do too much work. The whole of her working life has been spent in this same house and she dies in her little bed…a totally uneventful life…it was really wasted.’

De Paul felt disappointed in this past life. Everett-Alkin moved her on to another memory.

‘I’m looking at something carved in wood and I’m very, very small, I’m just about walking. I’m wearing white and someone’s bedroom; there’s lots and lots of carved wood, sort of Jacobean. I can’t tell if I’m a boy or a girl.’

The memory moved on to the age of ten.

‘I still can’t tell! I’m either a girl or a very feminine boy. I think it’s when they had a custom of dressing little boys the same way as girls. Yes, I’m a boy. I’m wearing laces and velvets and have long ringlets.

‘When I’m grown up I’m wearing Mozart-type clothes sitting in front of a keyboard. It’s a harpsichord, with two tiers with black notes and white notes, the reverse of a piano. I play by ear but I don’t compose. I’m the son of a quite well-t0-do family, so I don’t have to rush out to work early in life. My father exports textiles. He deals in cloth and wears a lovely long, dark wig with ringlets. He’s very dominant and I can see my mother.

‘By the time I’m thirty I’m married and live in the same house with my parents. There’s one child just been born and another a few years old. I’m now in the same business as my father. I see by looking at the huge family bible that it’s written in Flemish. I only play the harpsichord as a hobby now. My life has just followed the order of things.

‘By fifty my father is dead and I run the whole household. There are still only two children; there was a third but it died. The marriage is fine. It’s very cordial, although it’s never been very passionate on my part. I die in my late sixties of the gout, basically the body just stopped working properly.’

In the third regression De Paul returned to the same memory she had seen in a previous regression.

‘I’m seeing the same life very clearly that I had before when I was regressed by Dr Larive (Doctor of Metaphysics). It’s about 1720 and I’m a boy living just outside Hamburg. It’s not a very poor family. I’m wearing the style of the day, not dissimilar in fashion to the last life I saw, as it appears to be quite soon afterwards. It’s such a strong memory.

‘As a young boy I showed tremendous aptitude for music and was sent by my parents to study in Hamburg. I was sort of ‘gopher’ cum apprentice for the composers of that time. They weren’t very well known composers; there were loads of composers then whose work never survived them. I started out working for these sort of people. I can see the room I worked in: it was a small room with a table and a candle on it, a chair and a simple bed. I was set to copy out their manuscripts. The composer would write something and I would have to painstakingly write it out for them beautifully, a sort of calligraphy of music. I was apprenticed to learn composition, play the harpsichord and be a student of this person. I didn’t earn much but I just about got by. I was very happy as it was leading to good things and meant I wouldn’t have to be a peasant.

‘Eventually I ended up working and living in the palace in Hamburg. It was a huge and magnificent place. The room where I ate my meals was lovely but wasn’t nearly as wonderful as the dining hall where the owners ate. The servants were answerable to me, but I was answerable to the top echelon. They had very big wigs and lacy cuffs and I had a wig that had only two rolls on it and no lace on the cuffs. The big wigs really were the big wig wigs. I worked my way up there to become the resident musical director of that court, and if a maestro was coming to do a concert, they would send the scores on ahead with their servants and I would re-copy them, rehearse the orchestra from the harpsichord and then when the maestro came everything would be ready for him to just go and do his performance and I would step back for him. There was no accolade at all.

‘The most poignant memory is my snuff-taking habit. One always kept snuff in the left-hand pocket, then took it out in the left hand and flipped the lid open and took a pinch and put it on the back of the hand to sniff it up. Those with no lace were able to use the back of the hand, whereas if you had lacy cuffs you couldn’t put it on the back of the hand, so you would take just a pinch of snuff. I had a wonderful filigree snuff box measuring about two inches by one and a half inches, with a door that opened in it rather than the whole edge opening up, and it flicked up broadside not longside. There was a tremendous hierarchy involved in taking snuff because it was very expensive. It was actually snobbery. I don’t know whether I actually enjoyed it, but it did clear the sinuses.

‘I never married. There was a woman once, who was more of a friend than anything else, but I was attracted to both men and women, although I paid more attention to my career than to romance. I feel I was dedicated to my music and the court because of my low beginnings. It was my utter life: I loved the music and was a very competent musician. I wasn’t a great composer, just competent, and a good resident musical director. I didn’t hold any great sway, like I was anything of tremendous importance within the palace, but I held a position of rank. I lived in a wing of the palace where all the servants lived. My room was of oak but it was a very light oak; I suppose it went black over the years! It was a nice room with a lovely four-poster bed, but it had no top or canopy on it, just four posts going up to nothing. There was a desk and chair and a cupboard built into the wall.

‘I lived to a very ripe old age, mid-seventies, and died in my bed mainly due to old age. I felt very proud of myself because I had upheld my honour and been dedicated to my career and had approval from great people of that time and also royalty. I felt I achieved a tremendous amount.’

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.