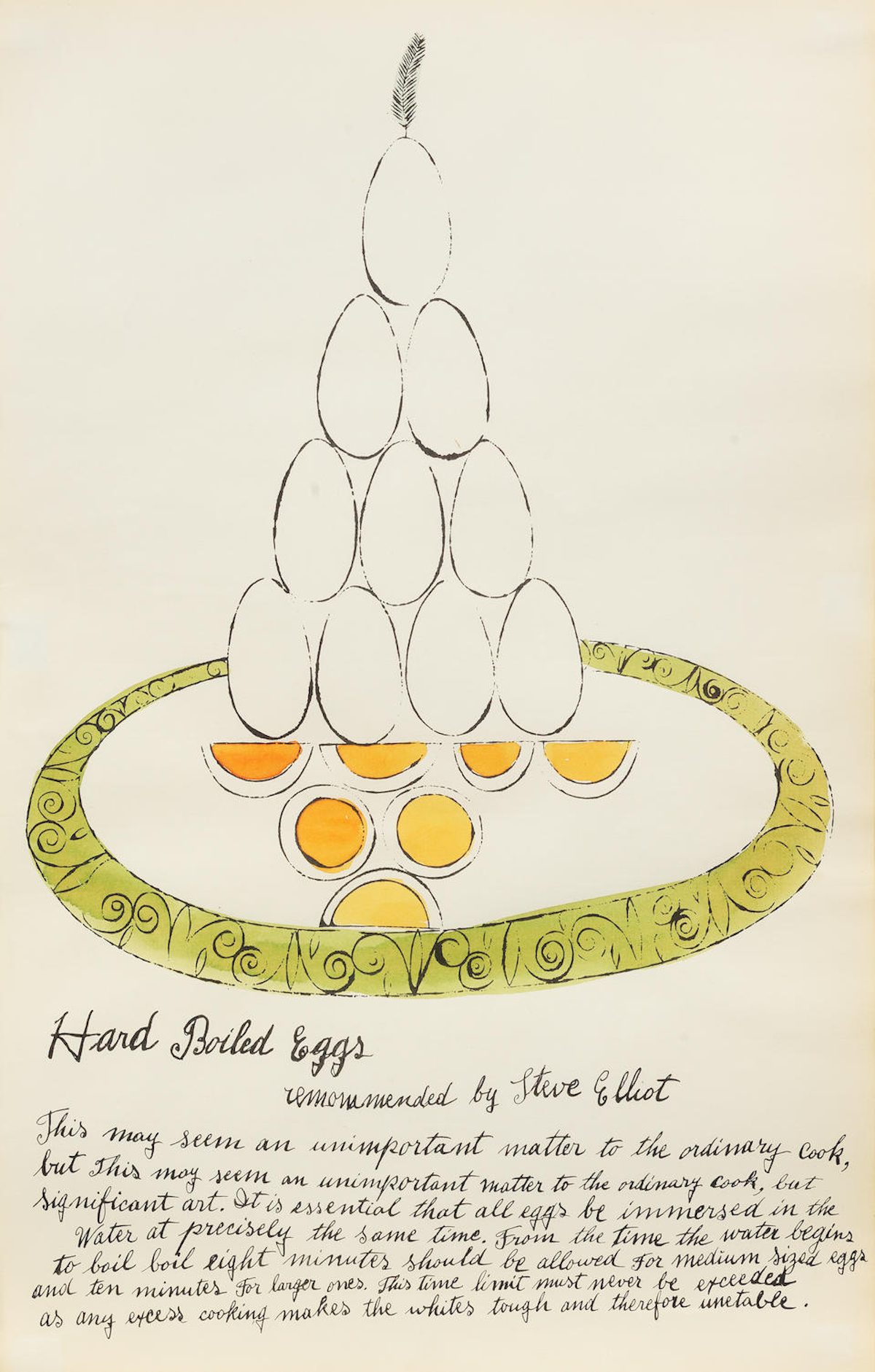

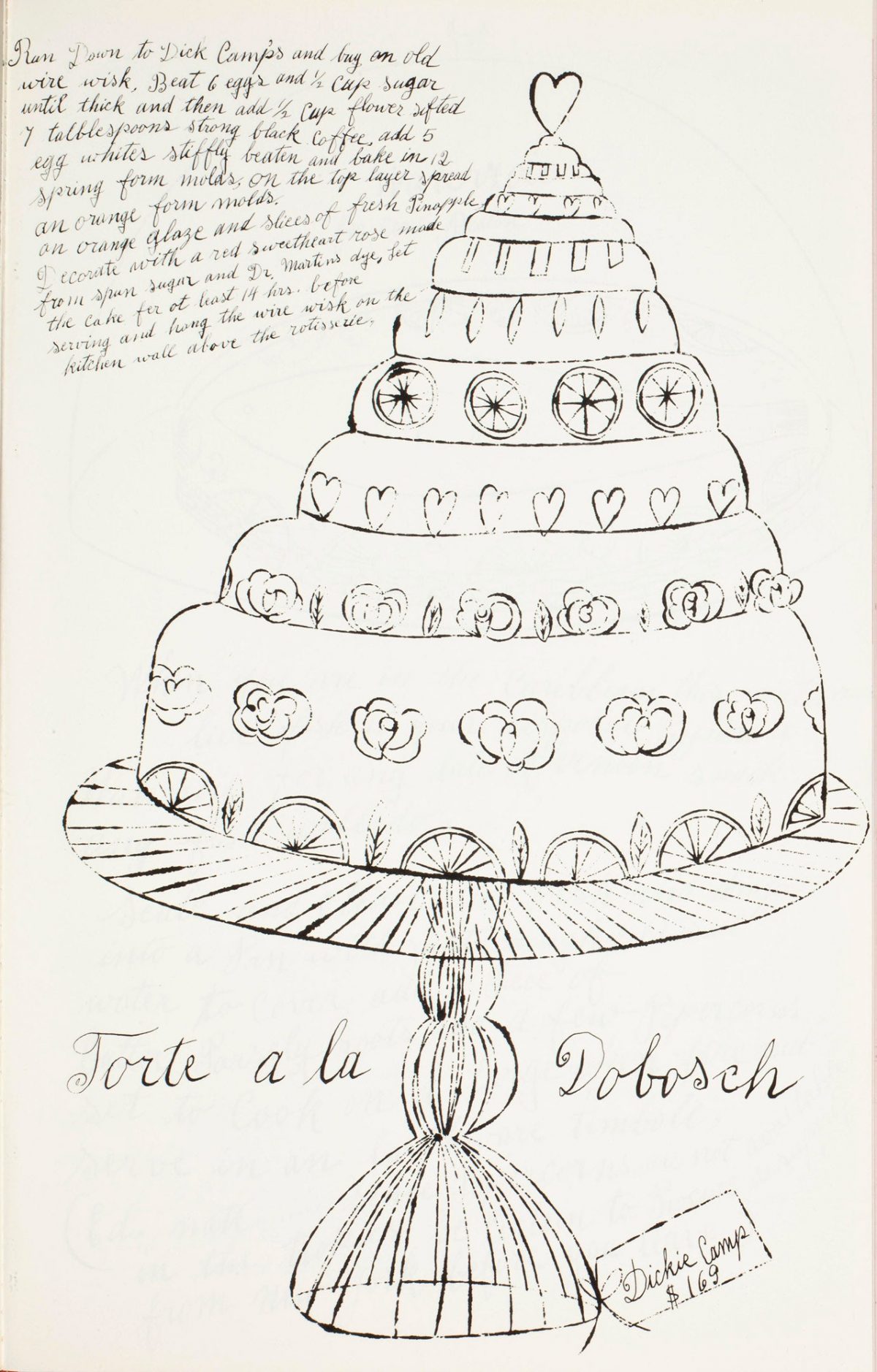

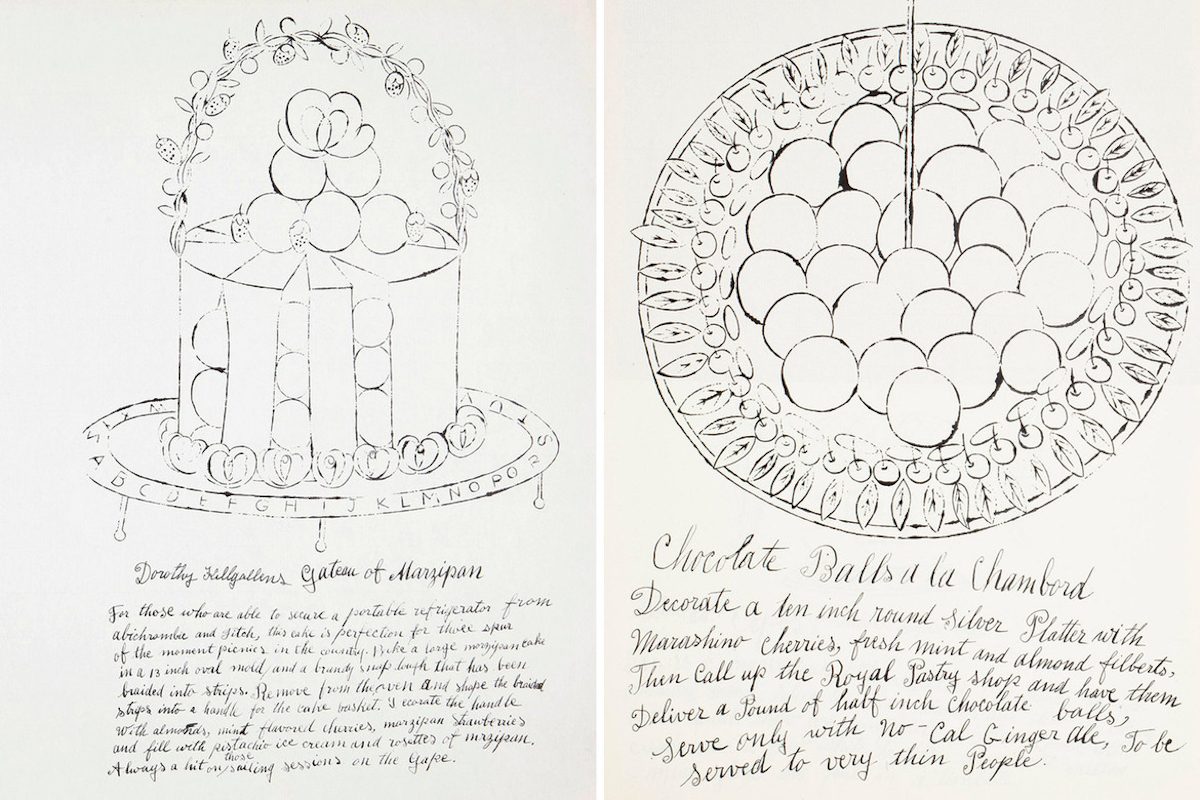

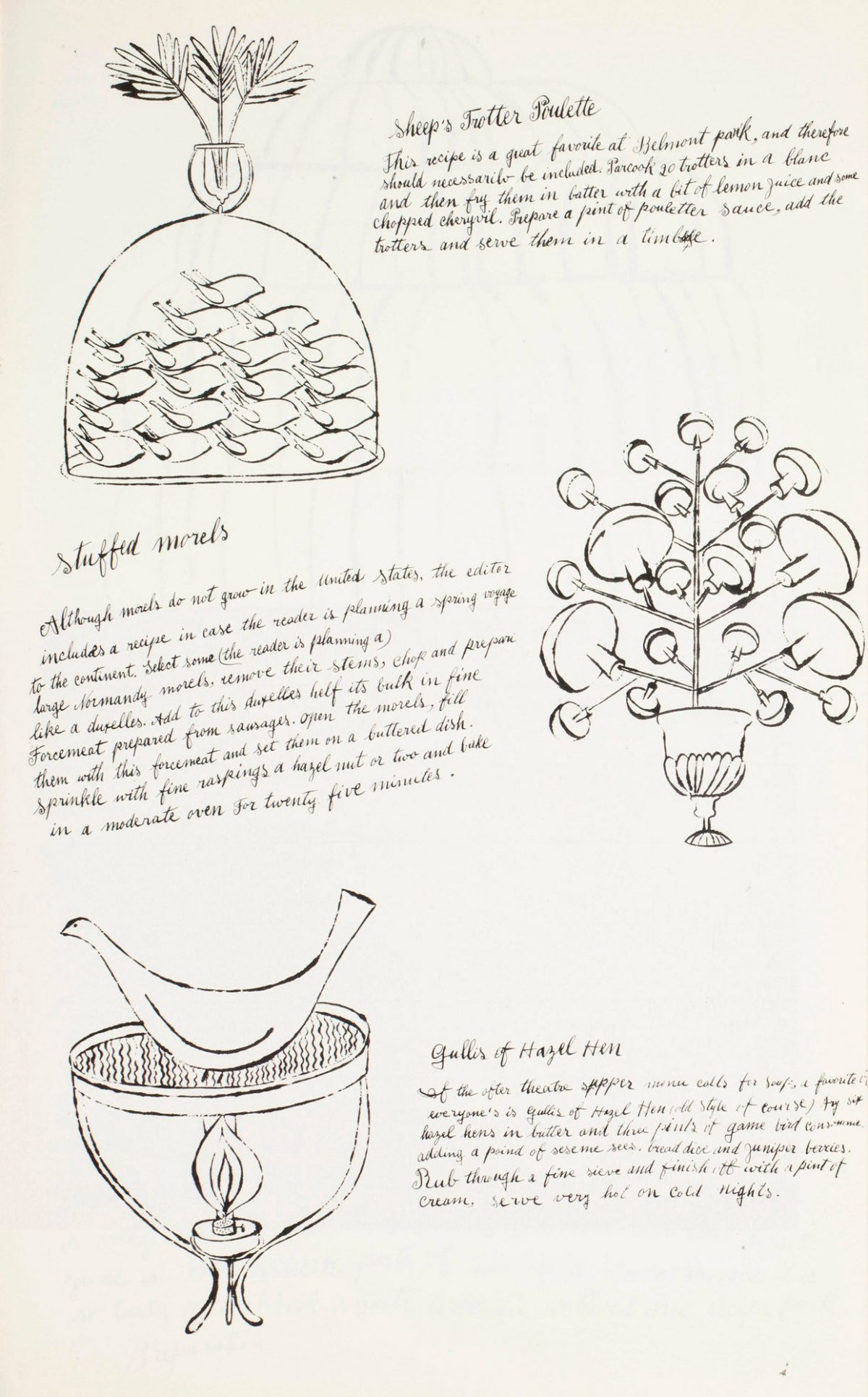

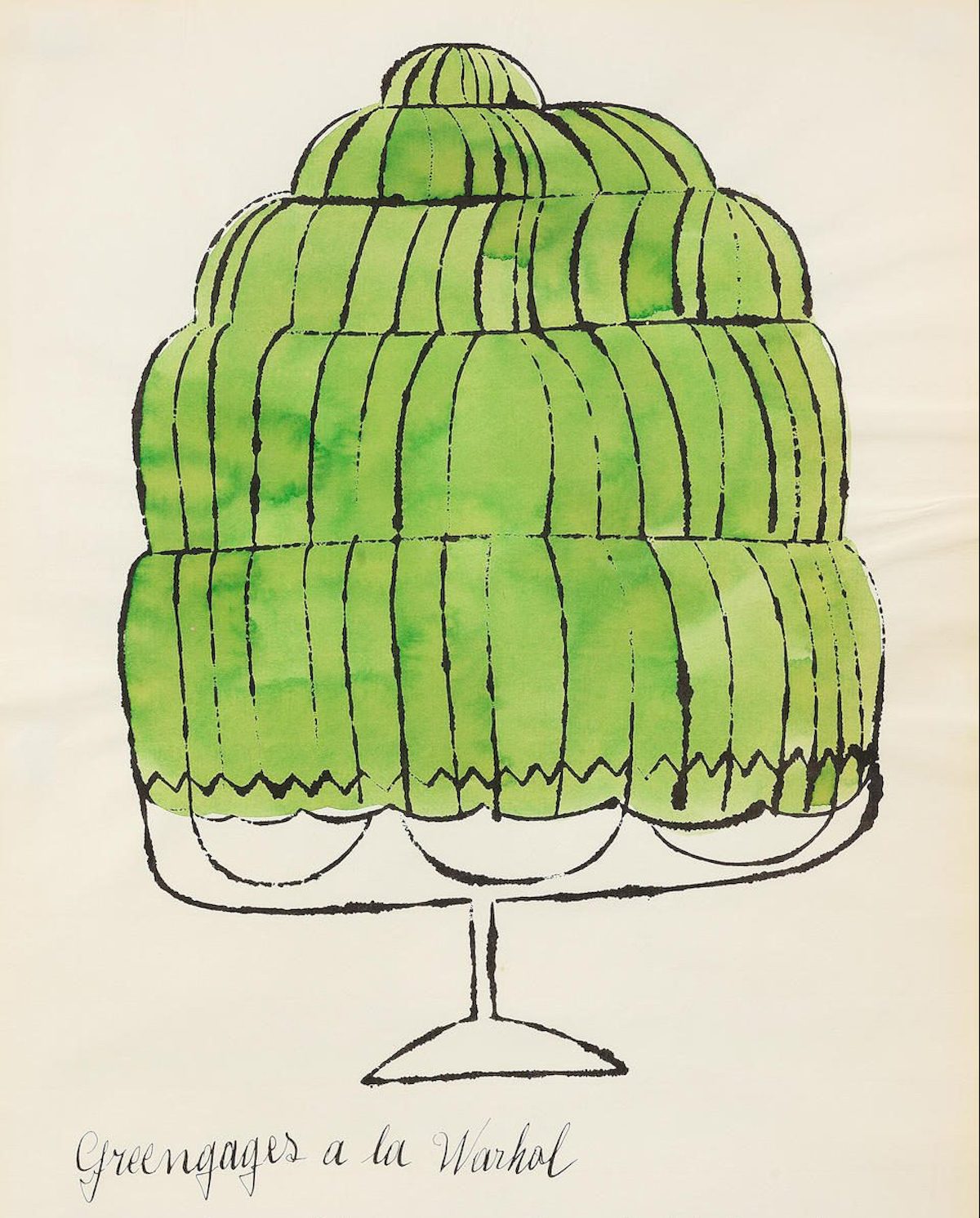

From Wild Raspberries, by Suzie Frankfurt, Andy Warhol, and Julia Warhola

Andy Warhol once appeared in a 1981 avant-garde documentary with a Burger King cheeseburger and a bottle of Heinz ketchup. You may recall the 4+ minute segment cut down to 45 seconds for a Super Bowl ad in 2019 (which Warhol might have approved had he been alive to ask). Such is Warhol’s continued relevance that he can sell fast food on TV during the most-watched televised event in the U.S., thirty-three years after his death.

The ad came with a hashtag: #EatLikeAndy. But ironically, Andy preferred McDonalds, a much more iconic American brand. He considered its packaging “the most beautiful,” just like Coke, which he liked as much for its level of brand awareness as for its taste. Fast food brands were great levelers, he argued in The Philosophy of Andy Warhol:

What’s great about this country is that America started the tradition where the richest consumers buy essentially the same things as the poorest. You can be watching TV and see Coca-Cola, and you know that the President drinks Coke, Liz Taylor drinks Coke, and just think, you can drink Coke, too. A Coke is a Coke and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking. All the Cokes are the same and all the Cokes are good.

That is, unless one prefers Pepsi. Warhol’s devotion to mass consumer culture was no act. There are stories of him routinely dining out at New York’s finest restaurants only to box up his entire meal and give it to a homeless person, probably while on his way to a McDonalds. As a dedicated anti-foodie, he also once illustrated a satirical cookbook mocking haute cuisine pretenses in 1959, before anyone knew who Andy Warhol was.

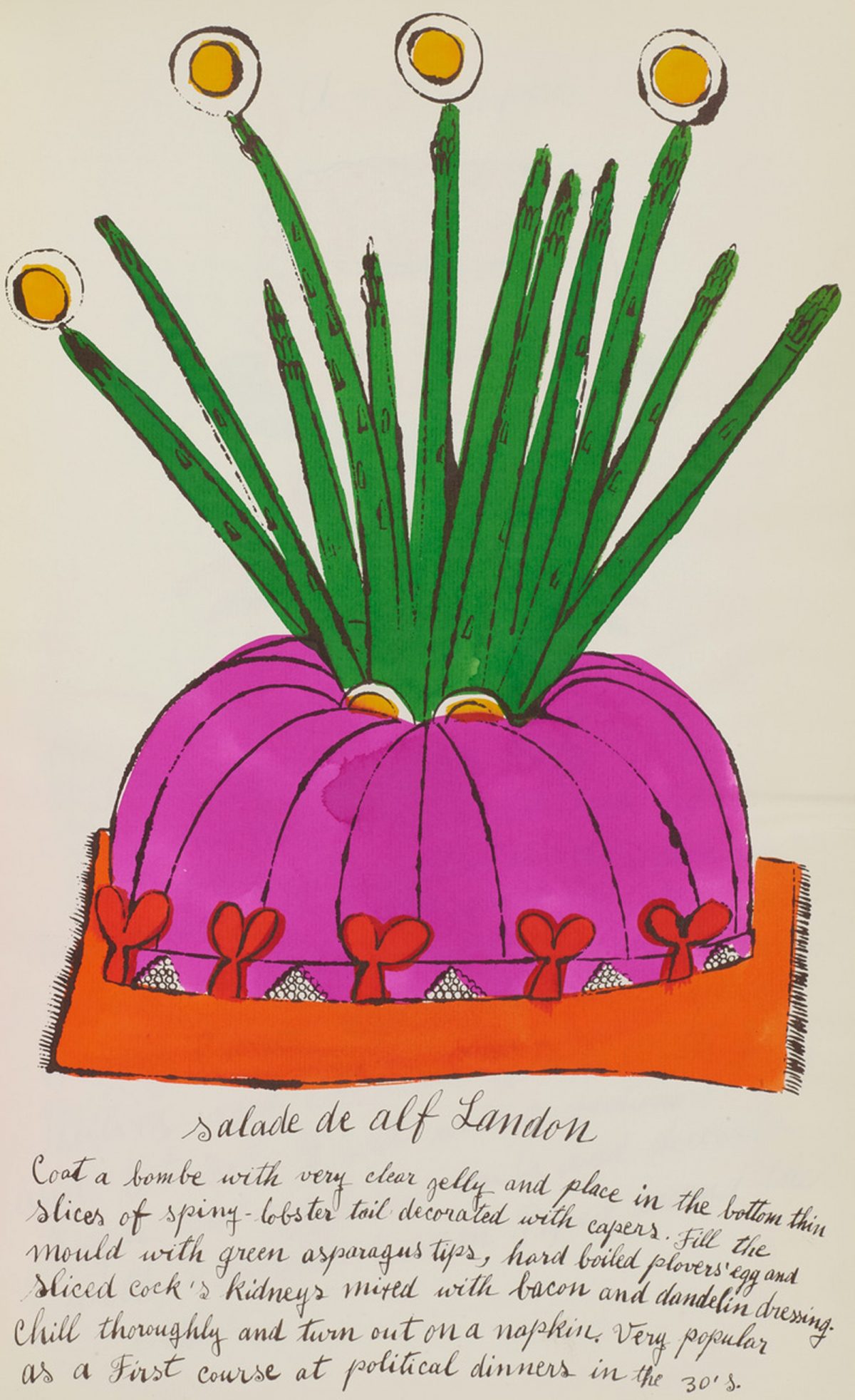

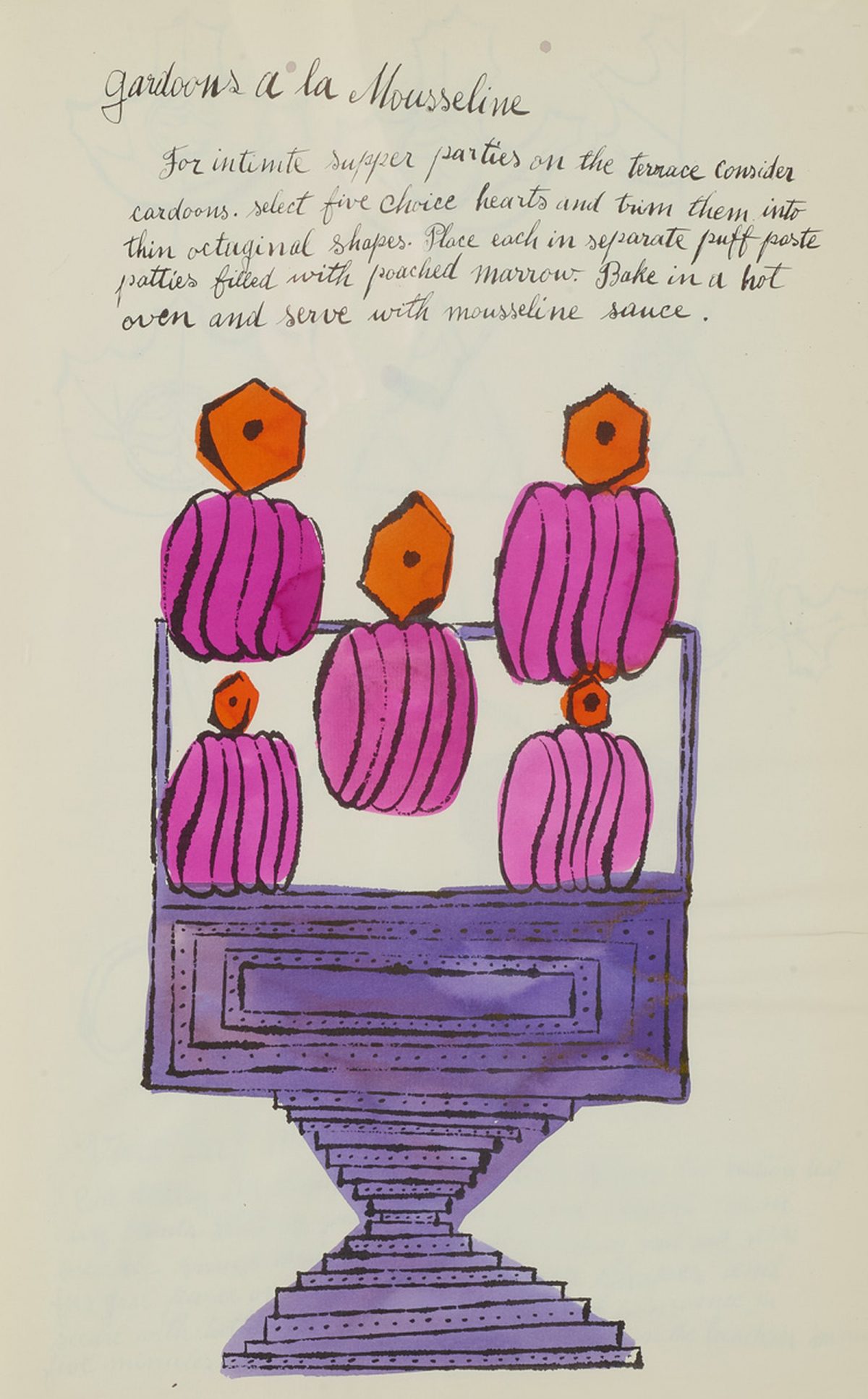

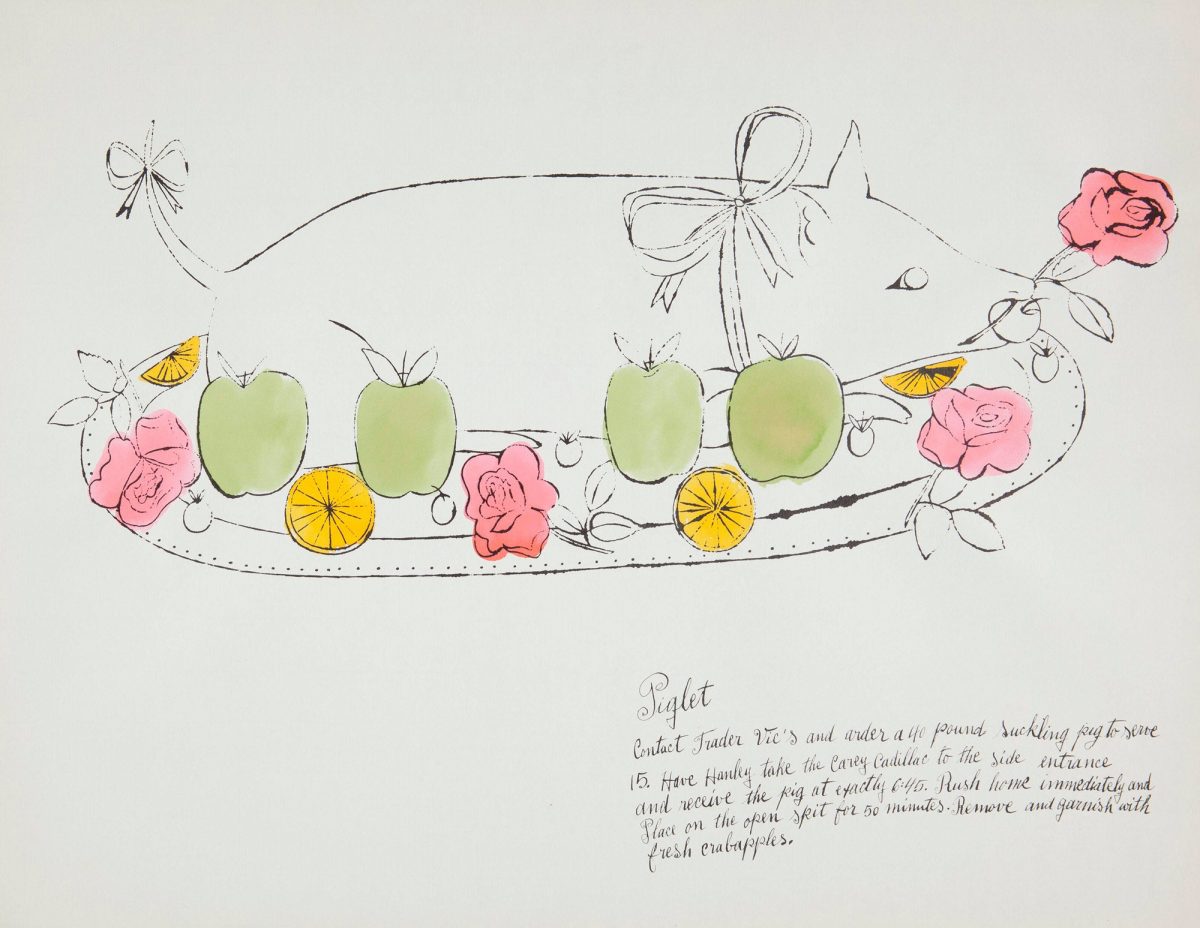

From Wild Raspberries, by Suzie Frankfurt, Andy Warhol, and Julia Warhola

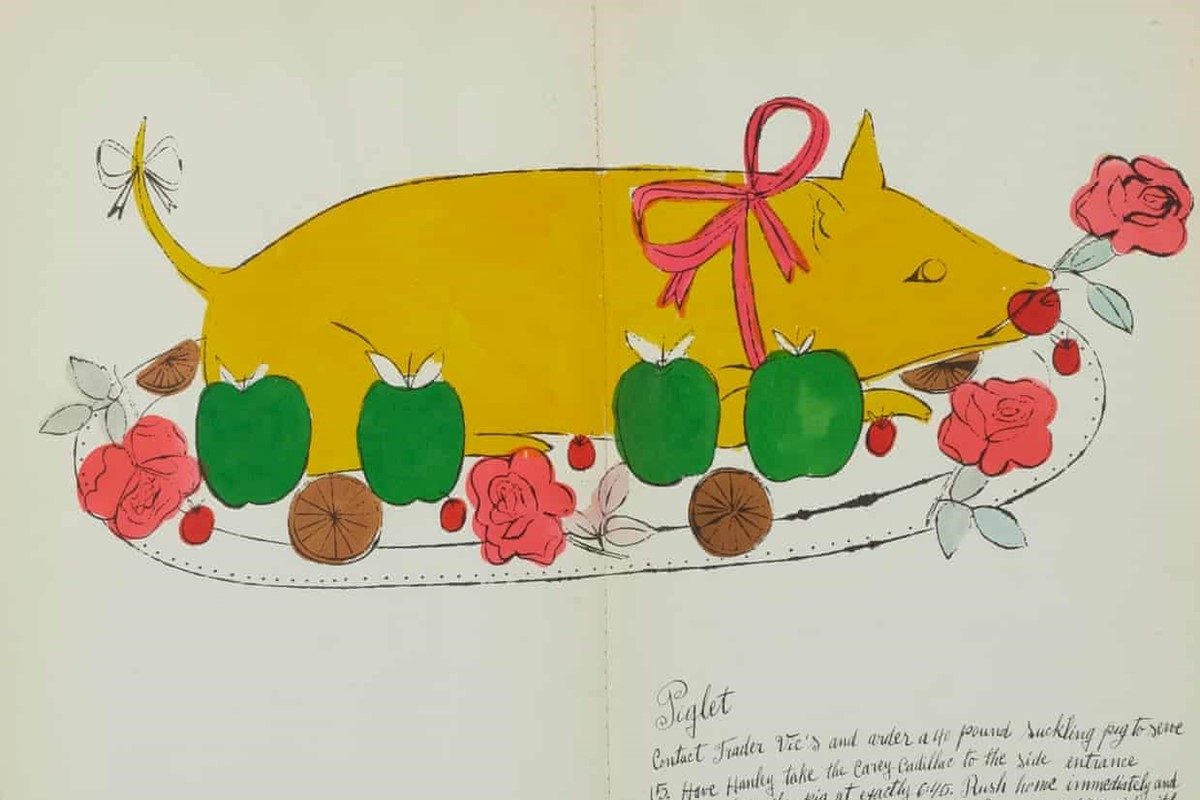

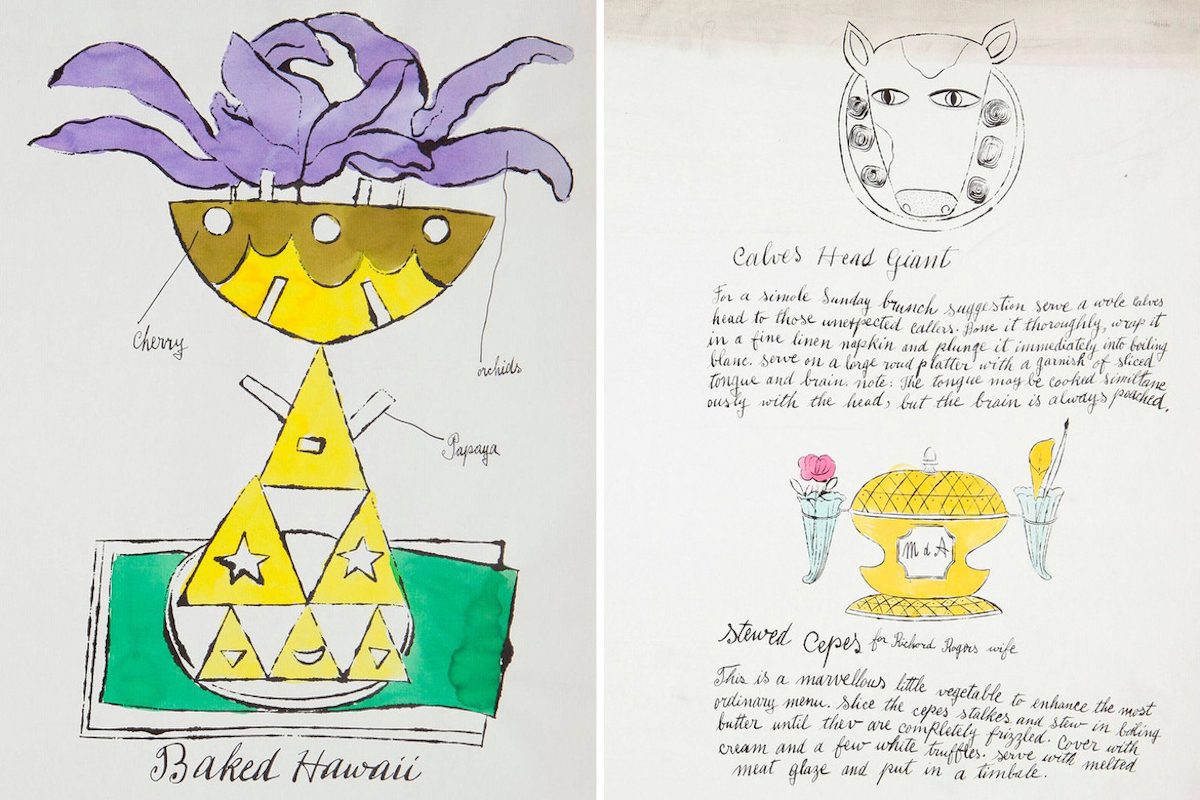

Called Wild Raspberries, the outlandish recipes were written by interior designer Suzie Frankfurt and included Edward Gorey-esque dishes like “Omelet Greta Garbo,” which is “always to be eaten alone in a candlelit room.” Warhol’s mother, Julia Warhola, did the book’s calligraphy, Thom Waite writes at Dazed, “with deliberate, whimsical misspellings.”

According to the auction house, only 34 editions were produced in colour, and many of these were given away to friends and associates, instead of being sold. “(They) were done in the spirit of fun, with a bit of self-promotion, and often given as Christmas gifts to friends and his graphic design clients,” Bonhams’ Darren Sutherland tells the Guardian. “A few sold through his favourite ice cream shop Serendipity, which moonlighted as an art gallery.”

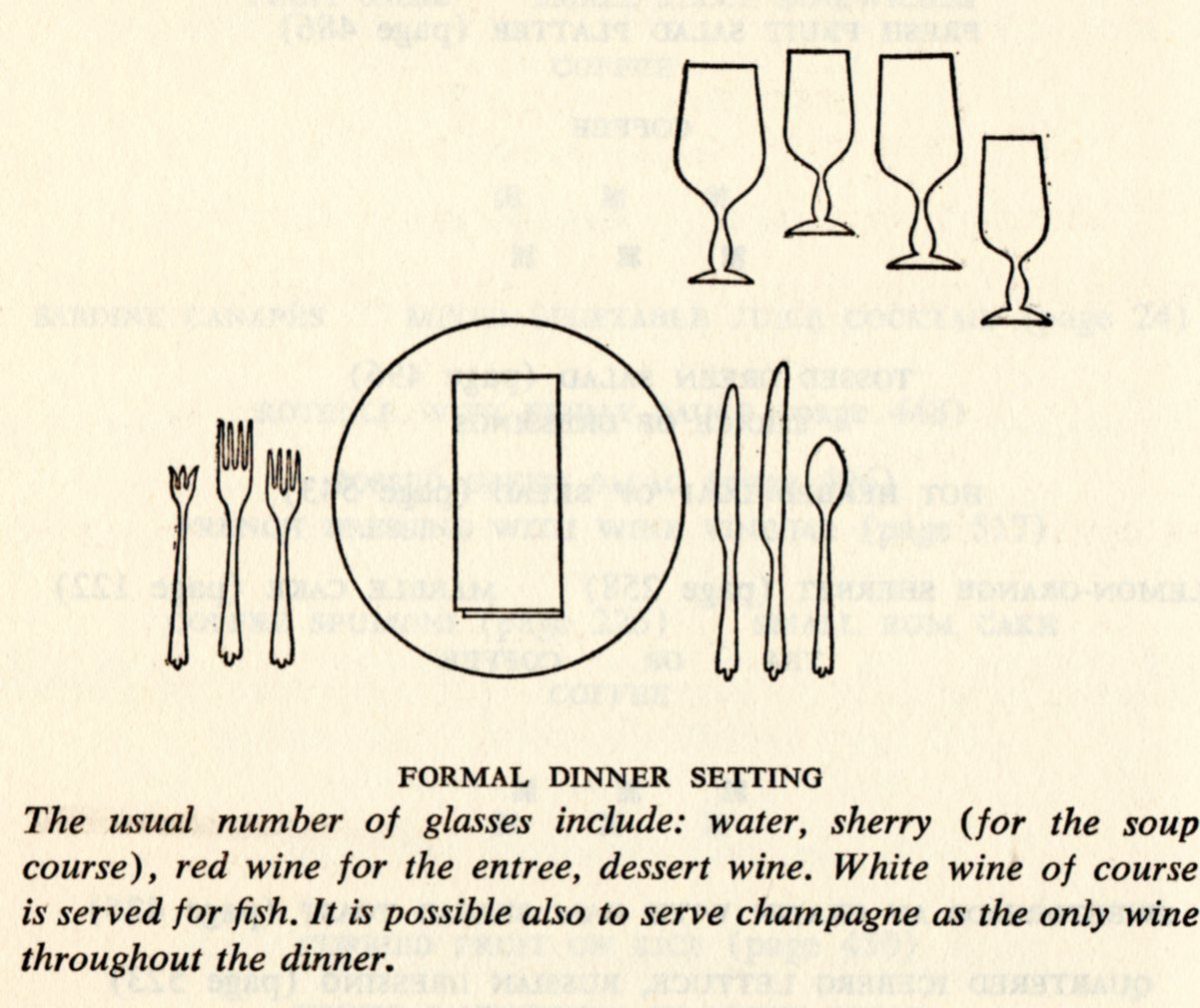

Always rare, the cookbooks are now even rarer, and like most things Warhol, fetch relatively high prices for such ephemeral early works. The same can’t be said for a mass-market cookbook that appeared two years later, for which Warhol also provided illustrations, exactly the sort of publication he had satirized in Wild Raspberries. The irony of profiting from this bit of work could not have been lost on him. The project, a purely commercial job, was for the definitively named Complete Cookbook, written by Amy Vanderbilt, the country’s foremost authority on etiquette (and author of a “complete guide” on the subject).

From The Complete Cookbook, by Amy Vanderbilt, illustrated by Andy Warhol

Warhol’s Vanderbilt illustrations are competently boilerplate and joyless next to the exuberant lines in Wild Raspberries. The contrast between the two styles – as between the two cookbooks’ wildly different tones — could not be greater. Warhol was not a snob, quite the contrary when it came to food. And in the years before his first major exhibition and early sixties breakout, he knew what it was like to work hard for a living.

But Warhol also genuinely revelled in banality and bright surfaces and admired the kitsch of fast-food design. He was, after all, a commercial designer, and his avant-garde sensibilities were always complemented, and eventually exceeded, by a keen commercial sense. (Even in 2020, he was the world’s best-selling artist, by a long shot.) Warhol knew good branding when he saw it, and he understood the comforting allure of repetition. But behind his appropriation of Madison Avenue’s best techniques lurked a charming quirkiness we rarely see on such full display is his work. See more of it in the illustrations from Wild Raspberries below.

From Wild Raspberries, by Suzie Frankfurt, Andy Warhol, and Julia Warhola

From Wild Raspberries, by Suzie Frankfurt, Andy Warhol, and Julia Warhola

From Wild Raspberries, by Suzie Frankfurt, Andy Warhol, and Julia Warhola

From Wild Raspberries, by Suzie Frankfurt, Andy Warhol, and Julia Warhola

From Wild Raspberries, by Suzie Frankfurt, Andy Warhol, and Julia Warhola

From Wild Raspberries, by Suzie Frankfurt, Andy Warhol, and Julia Warhola

From Wild Raspberries, by Suzie Frankfurt, Andy Warhol, and Julia Warhola

From Wild Raspberries, by Suzie Frankfurt, Andy Warhol, and Julia Warhola

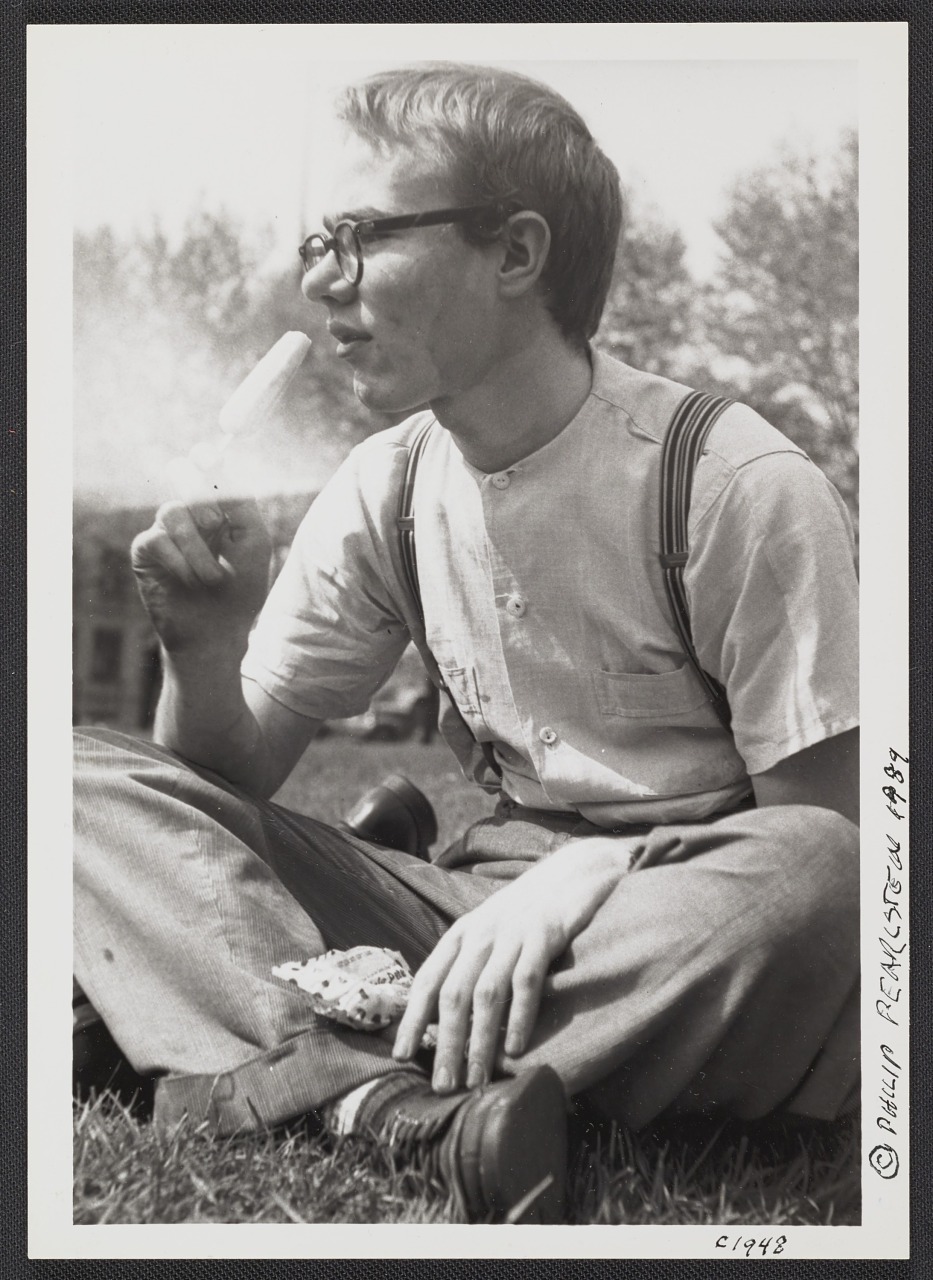

Philip Pearlstein. Andy Warhol eating a popsicle, 1948. Philip Pearlstein papers, circa 1940-2008. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.