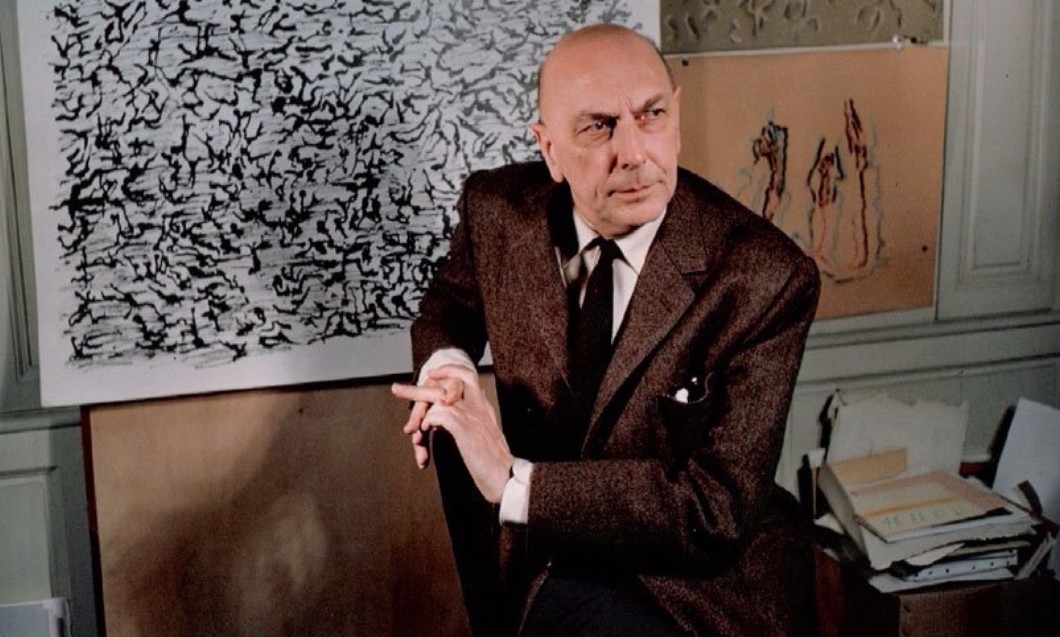

In 1963, Sandoz, the Swiss company that first synthesized LSD in 1938, commissioned poet and painter Henri Michaux (24 May 1899 – 19 October 1984) to create a film to show the power of hallucinogenic drugs. Michaux, Belgian by birth, but naturalized French in 1955, had taken psychedelic drugs, especially LSD and mescaline, which resulted in two of his best-known works, Miserable Miracle and The Major Ordeals of the Mind and the Countless Minor Ones.

Eric Duvivier, head of ScienceFilms, approached Michaux after reading Knowledge through the Abyss about the prospect of making a film about tripping on mescaline. Sandoz marketed LSD from 1947 through the mid-1960s under the name Delysid. The film would sell the drug to the medical community, who would, the company hoped, use it a psychiatrist’s tool. LSD had been hymned as a cure for mental disorders many times over.

In 1954, Time magazine reported beneath the headline Medicine: Dream Stuff on Sandoz product LSD 25:

In the current London Journal of Mental Science, three British psychiatrists, R. A. Sandison, A. M. Spencer and J.D.A. Whitelaw, discuss the results of treatment with LSD 25 on 36 psychiatric cases. Their conclusion: as an aid to psychotherapy, LSD 25 is the best of all such drugs so far tested.

Given a standard (25 micrograms) dose of LSD 25, the patient first shows the symptoms of an addict of hashi He starts giggling or crying, soon switches to silence punctuated by an occasional scream. He trembles, sweats, and shows every symptom of terrible anxiety. Then he goes into one of several “experiences”:

Patients can often recall and re-experience their childhood in clear detail. Wrote one woman: “I realized that I was reliving an incident that occurred when I was quite small, on holiday … I was not in the least surprised to see my hand and arm [become] quite little, about the size of a child of seven or eight . . .”

Others find themselves way back in time: “Part of me was detached…

When I looked at the doctor’s hand, the detached part of me saw it as it was, the other part expressed a feeling of horror . . . the hand was so old as to be ageless . . . There were sand and bright colors… Egyptian ornamentation and a sphinx… Still others experience identification with friends or relatives. Several patients thought themselves to be their own mothers, and two went through the experiences of their own birth.

No psychiatrist will go as far as Author Huxley (who prescribed mescaline for all mankind as a specific against unhappiness). But LSD 25, while it has no direct curative powers, can be of great benefit to mental patients. It encourages them to interpret their own soul-searing fantasies, and the newly revealed memories help the psychiatrist plan further treatment. Of the 23 cases that had completed treatment, LSD 25 coupled with psychotherapy resulted in 14 cases recovered, while one showed great improvement.

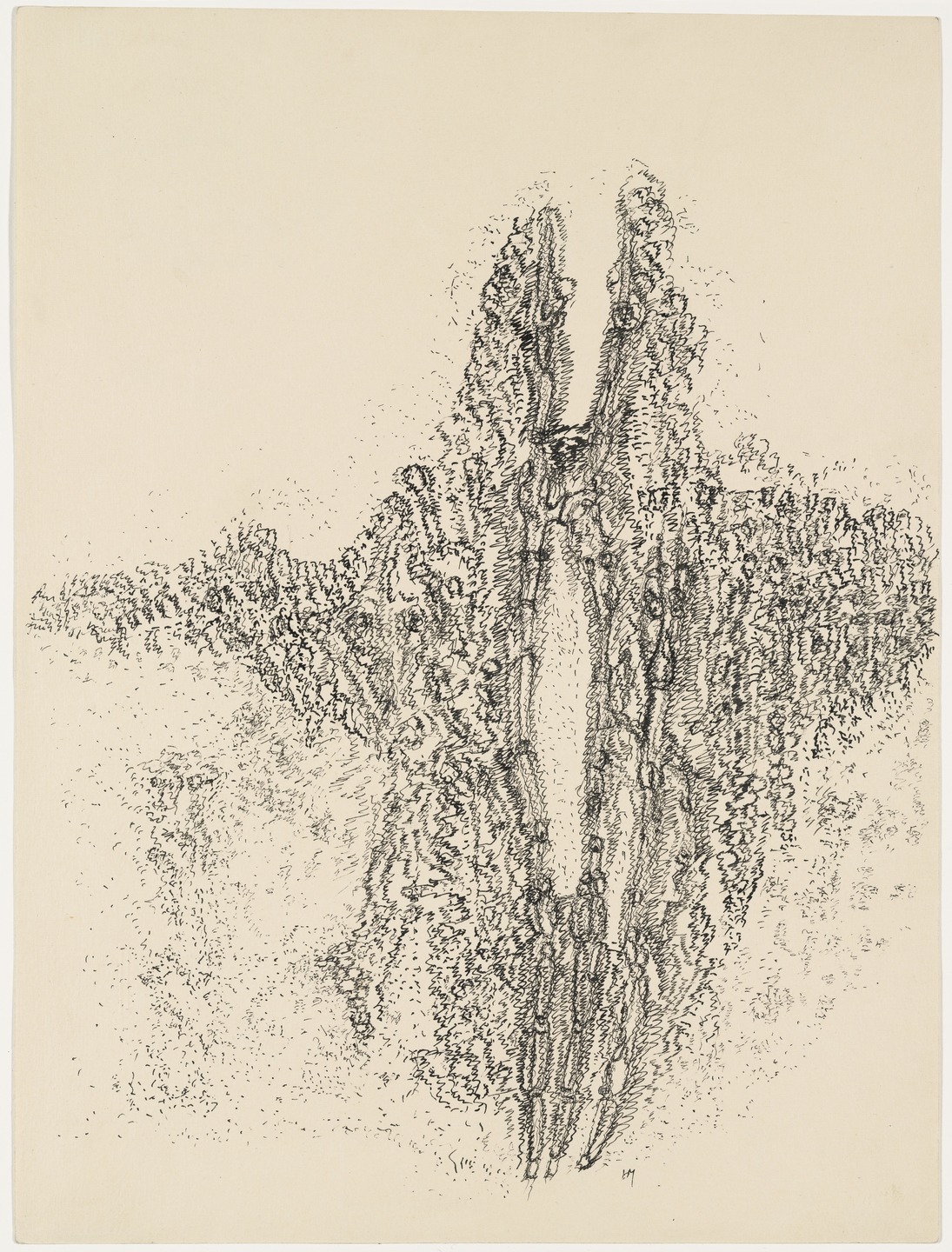

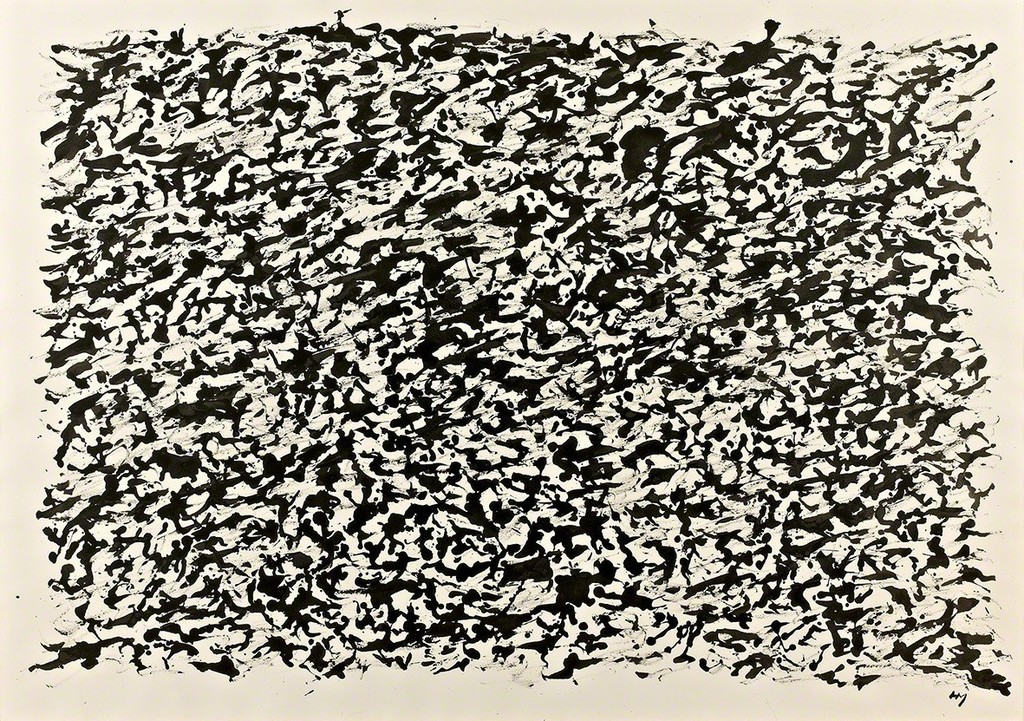

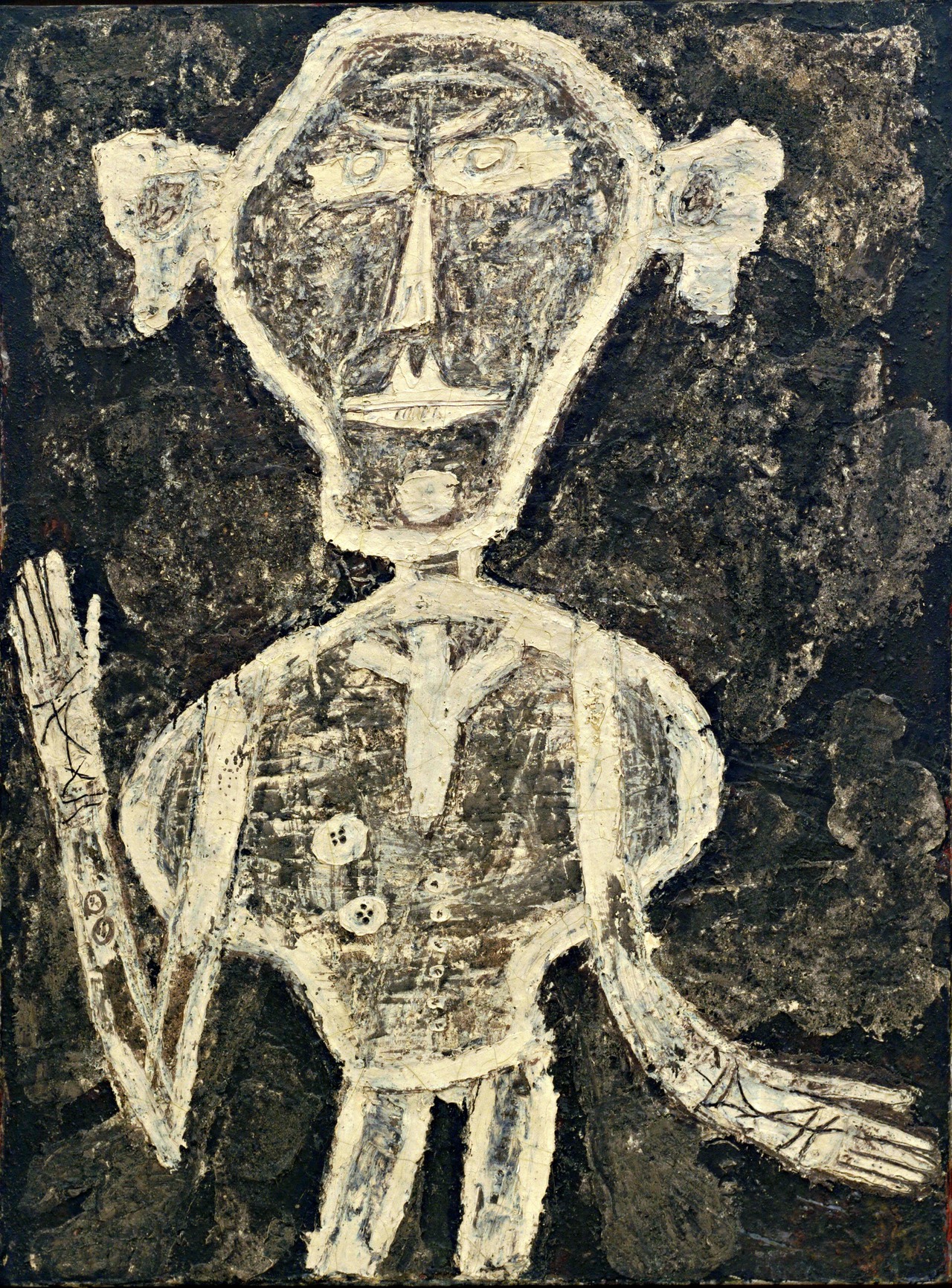

Michaux first took mescaline in 1948, after his wife died after accidentally setting fire to her nightgown. He kept a journal of his experiences on the drug – which he took compulsively over the next decade – accompanied by complementary line drawings. All his output was part of the whole vision. ”Can’t you see that I paint in order to drop words, to stop the itching of how and why?” he mused. He explained his art and writing as “cinematic … attempts to draw the flow of time.” Time jumps around when your on mescaline. “Speed!” exclaimed Michaux. “Can we forgo extreme speed? Can the Brain? For those who have experienced the unforgettable accelerated tempo of mescaline, speed invariably remains the problem, doubtless the key to many others.”

To Michaux mind-altering drugs were there to serve a purpose. Miserable Miracle opens with this phrase: “This book is an exploration. By means of words, signs, drawings. Mescaline, the subject explored.” Michaux was seeking to know what he called ”the space inside”. And drugs can open what Huxley had called the “doors of perception”. “Drugs bore us with their paradises,” wrote Michaux, “let them give us a little knowledge instead for this is not a century of paradise.”

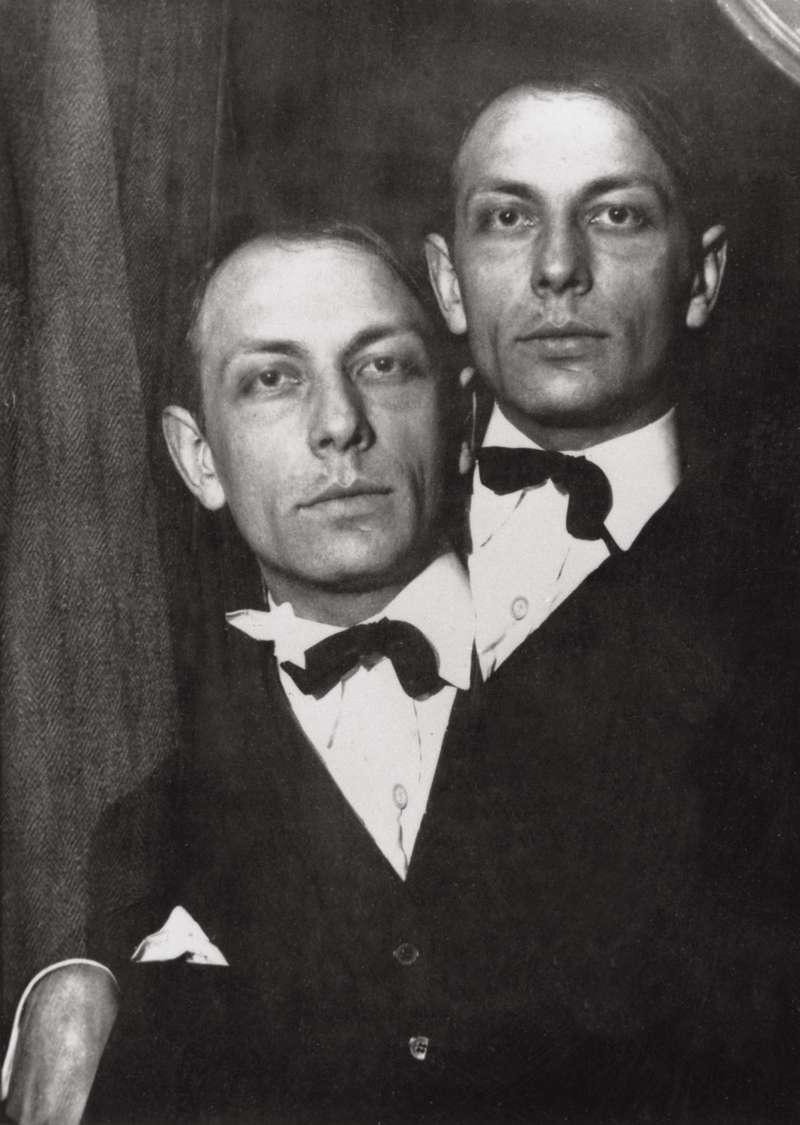

An earlier insight into Michaux’s quest for self-knowledge came on October 9, 1943, when he and Hungarian-born photographer Brassai met Pablo Picasso in Paris. “I don’t see anyone in the younger generation who has Picasso’s stature as a draughtsman, or Matisse’s or Braque’s stature as a colourist,” said Michaux. “But perhaps we don’t want the same thing, we’re not aiming for the same thing anymore. Picasso is as genius, that’s obvious, but his ‘monsters’ no longer trouble us. We’re looking for different monsters and by different paths.”

“He strikes me as being one of the most palpably authentic of post-war European artists,” wrote the art critic Peter Schjeldahl of Michaux in the The New York Times in 1975. ”Influenced by Ernst and Klee, he created an art of energized ideograms and meandering calligraphy, of figures evolving haphazardly out of weltering chaos, or of the chaos asserting itself to wipe out.”

Henri Michaux introduced Images of a Visionary World thus (via):

When someone proposed that I make a film about mescaline visions, I repeated again and again that it would be an impossible undertaking. This drug is beyond anything we could possibly create. I would say that even a superior film, made with much more considerable means and with all that is necessary for an outstanding production, would be insufficient for these images. They are more dazzling, more unstable, more subtle, more labile, more imperceptible, more oscillating, more trembling, more martyring, more swarming, more infinitely charged, more intensely beautiful, more terribly colored, more aggressive, more idiotic, more strange. As for the speed, it is such that all the sequences together should take fifty seconds.

Here cinema becomes impotent, especially since one would need to increase all these characteristics at the same time. The images in the film are thus very sober, slowed down, attenuated, simple indications of the visual formations by which, almost without fail if the dose taken is sufficient, the drug images will occur. It doesn’t matter if the subject is a genius of the inner life or a plain and simple man. We did not attempt to represent the general and profound effect on the personality -such a film would be entirely different — but rather the types of images that one commonly encounters in these states. It will suffice to show how considerably these visions differ from those of the dream, and, in a certain way, those caused by hashish, and in what ways they coincide with those that some psychotics have reported. This is the justification behind our attempt. Before there was nothing; next time we will be able to do better. Although the mescaline visions ordinarily pass in

absolute silence, it is not without reason that music has been introduced. It has a role to play.After the protagonist ingests mescaline, 15 minutes of mescaline-inspired sounds and image

Whether the subject becomes apathetic, blissful, jovial, or restless, the visionary images invade, animated this time, not by a vibratory movement, but by a rousing movement. That which is disproportionately elongated, which is exaggeratedly high, which fuses, streams out, precipitates; an extreme, crazy, irresistible animation, always ready to take flight; the unexpected, the funny, the immense, the marvelous; endless corridors, terraces as far as the eye can see, chasms, fabulous palaces, incessant, amazing metamorphoses; the unusual, especially the unusual: this is the realm of hashish. We hear murmurs, real voices sometimes. Some of the noises relate to the visions, but not constantly, not strictly, often delayed. Similarly music, just beginning, soon ends in a dizzying and comedic amalgam. Periodically everything stops — sound and light, or one without the other — as if it were gathering its forces. From this fantastic parade, more fleeting than enigmatic, we have imperfectly and with extended gropings, reconstituted a few parts.

After the protagonist ingests hashish, 15 minutes of hashish-inspired sounds and images

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.