John Steinbeck liked to write with a pencil. He sharpened twenty-four pencils every morning with which he would do his day’s work. With one pencil he could write a full-page on a yellow legal pad before the point was blunt. His writing was tiny. Crabbed up knots that sometimes needed a magnifying glass to decipher. Steinbeck said he once managed to squeeze five-hundred words onto the pack of a holiday postcard. I suppose you could say he was mean, but an early life of hard work and poverty had taught him to be frugal.

Steinbeck limbered-up each day by writing letters. He wrote thousands of letters during his lifetime. Once the letters were written, he was ready to start writing. Steinbeck wrote without thought to spelling or punctuation. That was the job of a stenographer to fix when he handed in his manuscripts. He once wrote a friend:

I want to speak particularly of your theory of clean manuscript and spelling as correct as a collegiate stenographer and every nasty little comma in its place and preening of itself. I have the instincts of a minstrel rather than those of a scrivener. When my sounds are all in place, I can send them to a stenographer who knows his trade and he can spell the words so that school teachers will not raise their eyebrows when they read them. Why should I bother?

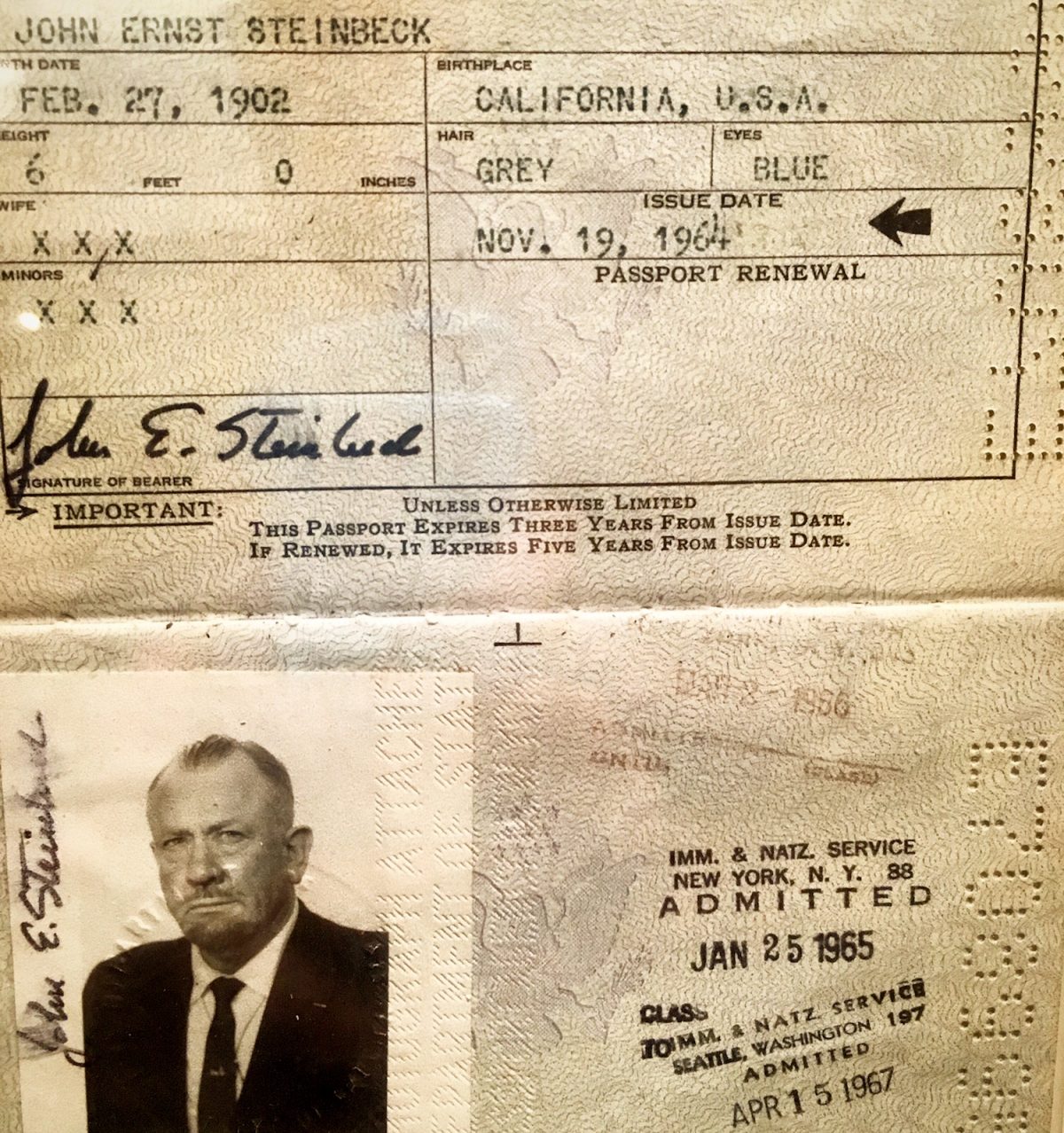

When Steinbeck was twenty-four, he decided to become a writer. He recognised this meant spending a lot of time on his own. He worked at various jobs to finance his ambitions. He avoided social contact maintaining his friendships through letters. He worked by day and wrote by night.

One job was to change his life. One autumn, Steinbeck was employed as a caretaker at a large estate on Lake Tahoe. He was snowed-in for eight months. His nearest neighbour was four miles away. He used his time in isolation to write his first novel Cup of Gold.

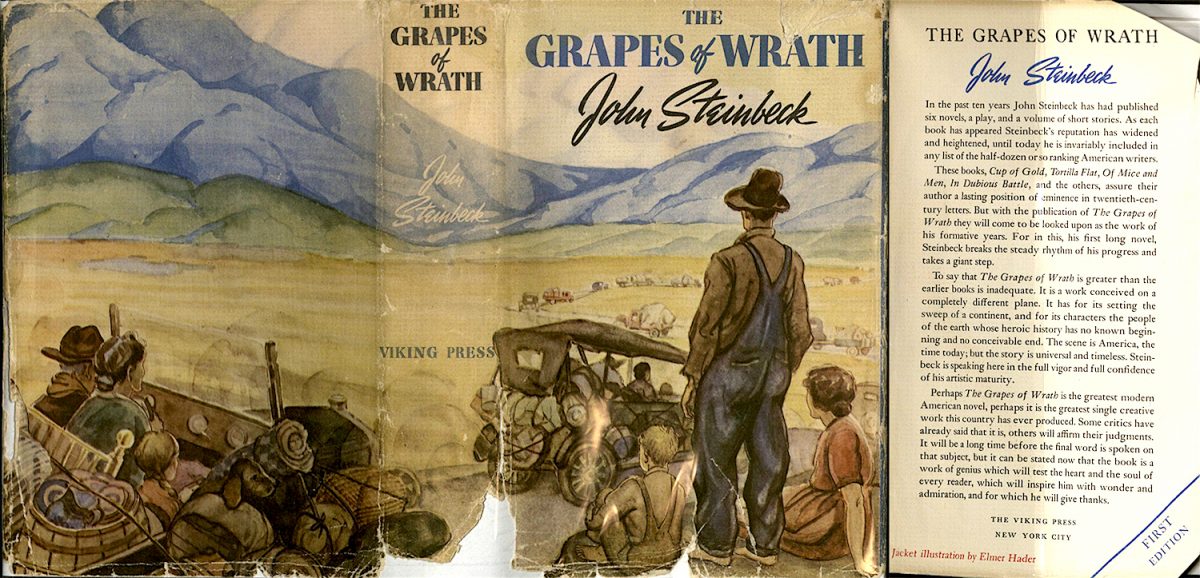

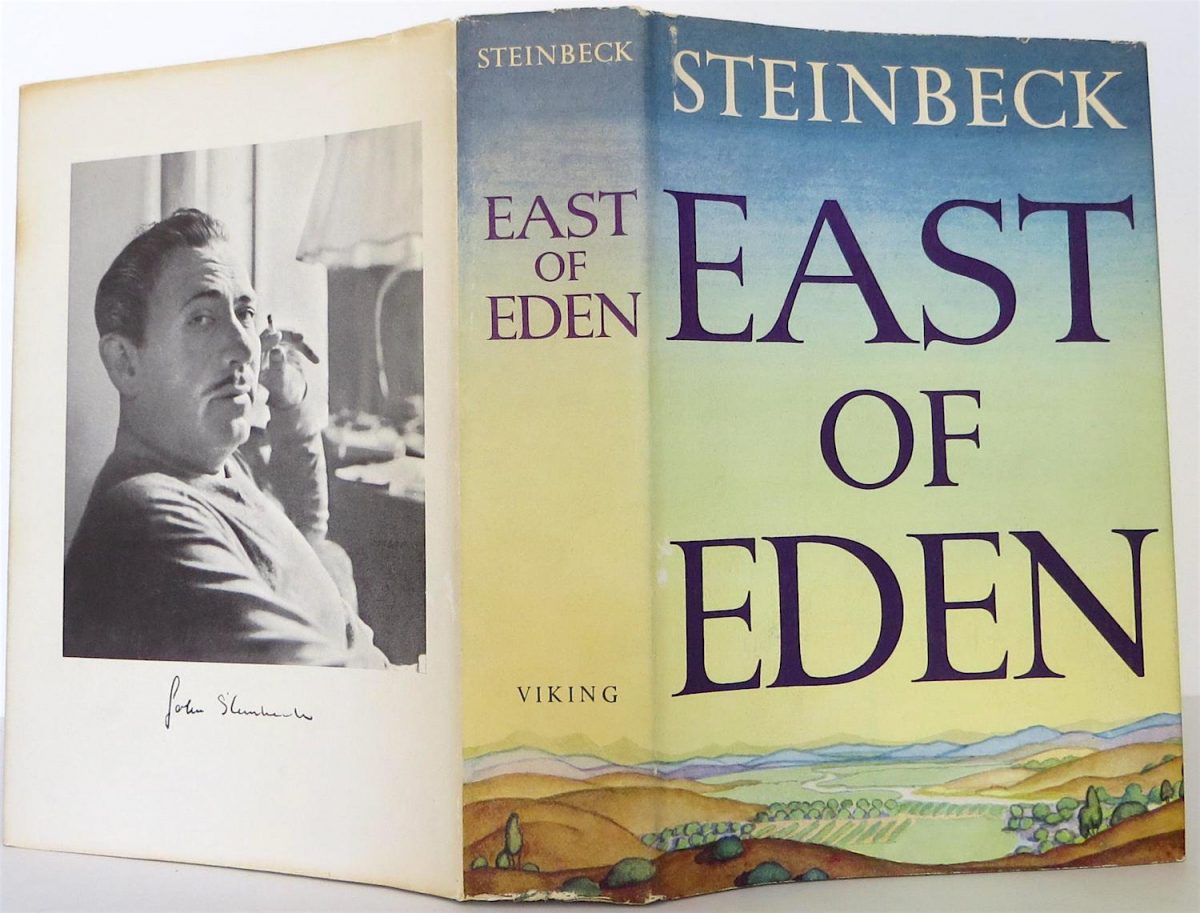

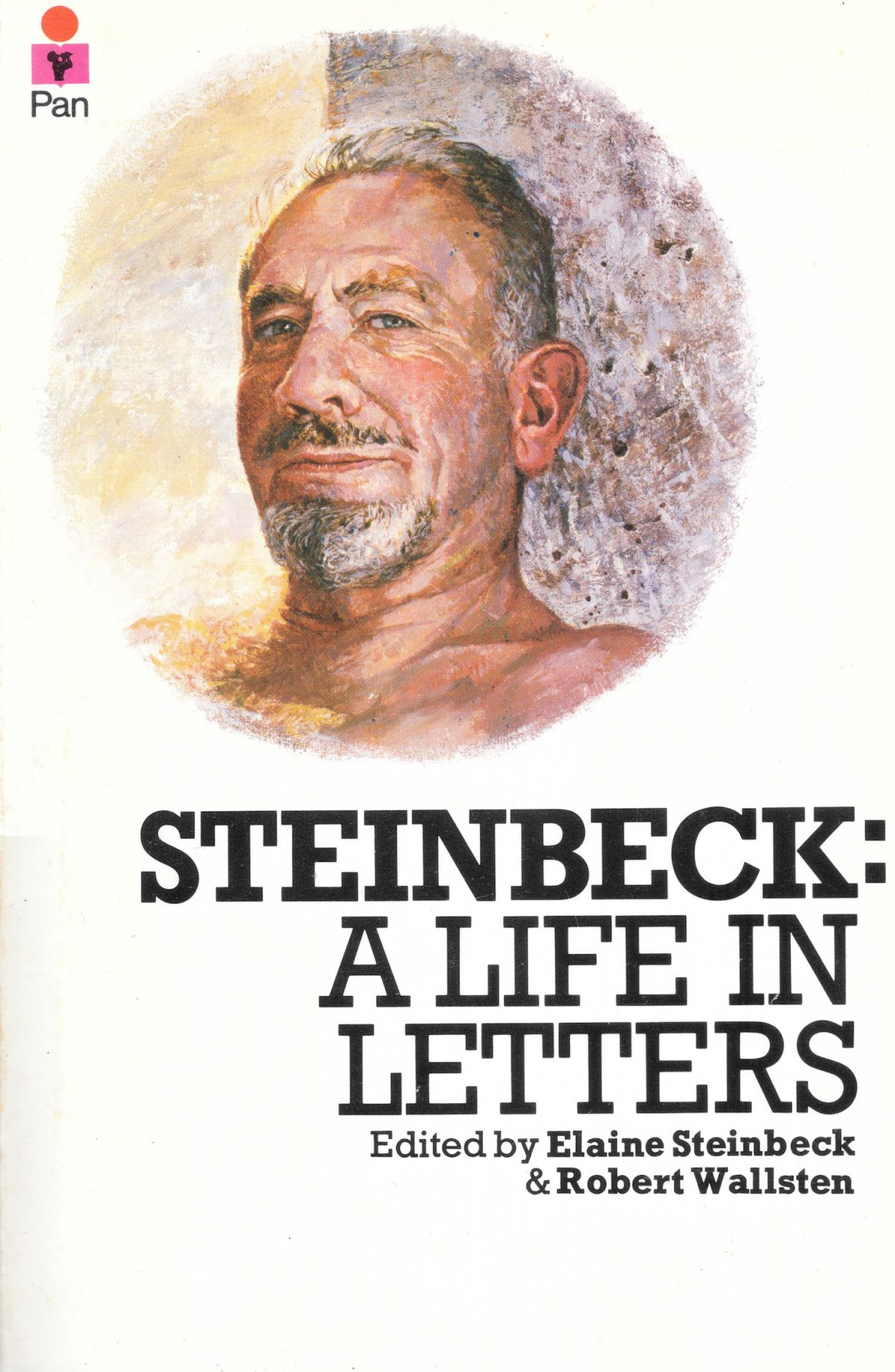

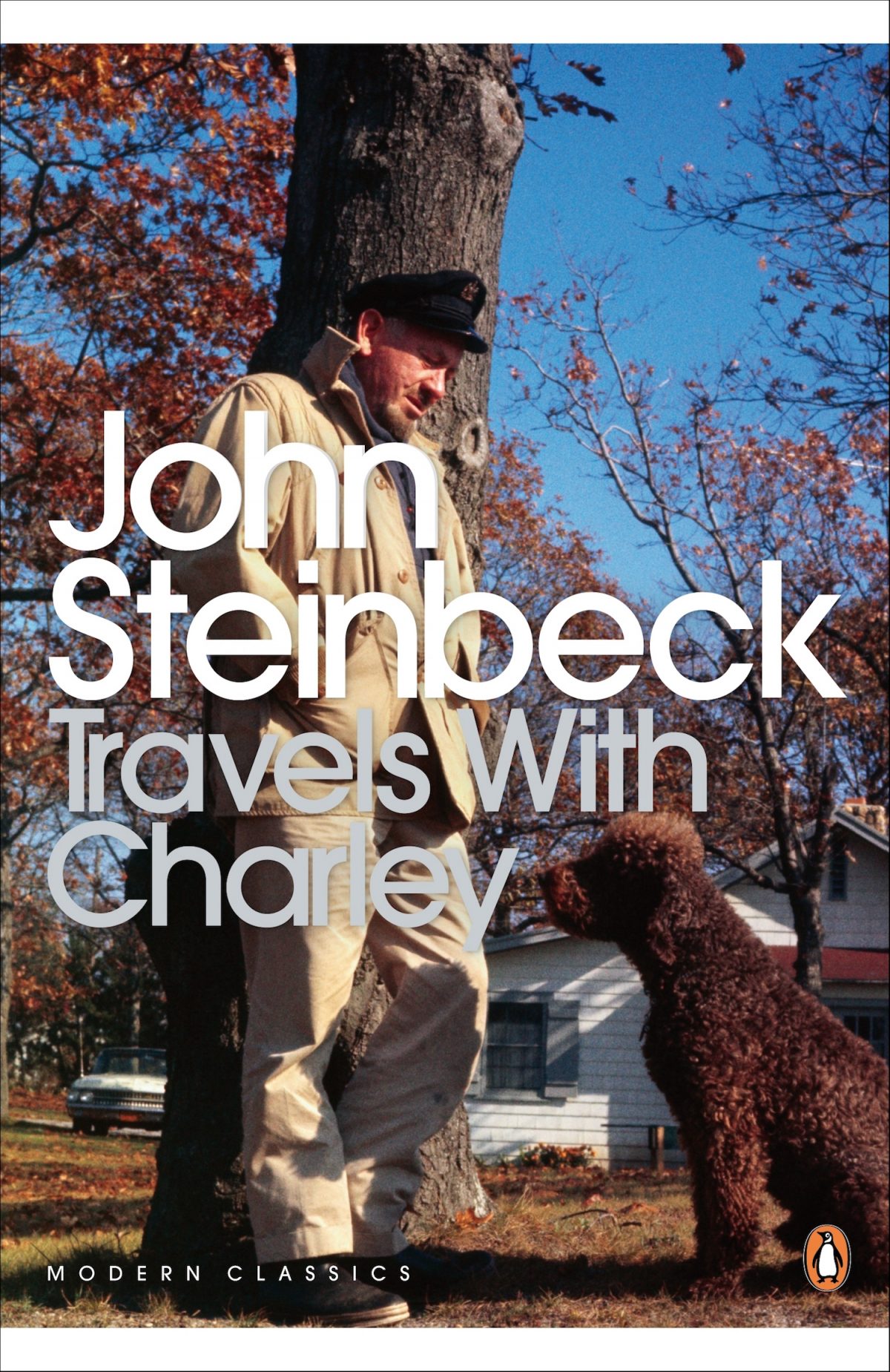

It was a start and we all know how it went from there. One of my favourites among Steinbeck’s many books is his massive volume of correspondence A Life in Letters. It’s one of those books I’ve read at leisure more than once and keep handy to dip in-and-out of for pleasure.

Steinbeck’s letters give considerable insight into his life, literature, struggles, success, travels, love and relationships. His mind fired with so many ideas it is surprising he ever had time to write his novels. His letters are also full of advice and clever observations.

In the dark the other night I wrote in my head a whole dialogue between St. George and the Dragon. Very close relatives those two. Neither could exist without the other. They are eternally tied together–actually two parts of one whole. I guess the Greeks had the truest conception of that in the centaurs, the man partly emerged from the beast. But you will notice centaurs steal and screw only women never fillies. So the urge is toward man and away from the beast. So St. George must always kill the dragon and it must be repeated because if the dragon were finally killed, there would be no St. George–only a lonely man looking for something to do.

As for the advice, well, responding to a letter from Robert Wallsten, a young man who was “experiencing a kind of stage fright about actually starting to write a biographical work,” Steinbeck gave the following advice.

Villa Panorama

Capri

February 13-14, 1962Dear Robert:

Your bedridden letter came a couple of days ago and the parts about your book, I think, need an answer…

…let me give you the benefit of my experience in facing 400 pages of blank stock—the appalling stuff that must be filled. I know that no one really wants the benefit of anyone’s experience which is why it is so freely offered. But the following are some of the things I have had to do to keep from going nuts.

1. Abandon the idea that you are ever going to finish. Lose track of the 400 pages and write just one page for each day, it helps. Then when it gets finished, you are always surprised.

2. Write freely and as rapidly as possible and throw the whole thing on paper. Never correct or rewrite until the whole thing is down. Rewrite in process is usually found to be an excuse for not going on. It also interferes with flow and rhythm which can only come from a kind of unconscious association with the material.

3. Forget your generalized audience. In the first place, the nameless, faceless audience will scare you to death and in the second place, unlike the theater, it doesn’t exist. In writing, your audience is one single reader. I have found that sometimes it helps to pick out one person—a real person you know, or an imagined person and write to that one.

4. If a scene or a section gets the better of you and you still think you want it—bypass it and go on. When you have finished the whole you can come back to it and then you may find the reason it gave trouble is it didn’t belong there.

5. Beware of the scene that becomes too dear to you, dearer than the rest. It will usually be found that it is out of drawing.

6. If you are using dialogue—say it aloud as you write it. Only then will it have the sound of speech.

Well, actually that’s about all.

I know that no two people have the same methods. However, these mostly work for me…

love to all there

John

1962 was a good year for Steinbeck. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature. At his acceptance speech, given at the City Hall in Stockholm, 10th December 1962, he said:

Literature was not promulgated by a pale and emasculated critical priesthood singing their litanies in empty churches—nor is it a game for the cloistered elect, the tinhorn mendicants of low calorie despair. Literature is as old as speech. It grew out of human need for it, and it has not changed except to become more needed.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.