Before Nick Cave became an elder statesman, goth troubadour, novelist, and surprisingly wise and compassionate advice columnist, he was l’enfant terrible of Australia’s burgeoning post-punk scene, first with The Boys Next Door, then with The Birthday Party, a band characterized by madness and excess like few others. “What made The Birthday Party so important,” writes Daniel Lovatt at Far Out, “is that they weren’t rioting at monarchy or government, they were simply rioting. An undiagnosable angst, which separated them from the products of punk rock that came before. With no reference point, the inimitable vampires could not be imitated, not even by themselves.”

Cave put things more succinctly in a 1982 interview, saying of The Birthday Party’s third and final studio album Junkyard, “It makes a stand for violence for its own sake and violence as a profession… it’s irresponsibly violent…. I think there’s a certain irresponsibility about the group in that we can incite a violent reaction or incite an energy into a crowd and just leave it at that without giving the crowd any aim or purpose or channel to focus their energy and violence upon.” Contrast this with the “contemplative, compassionate and touching” figure Cave has become online of late.

Artists grow and change, of course. In the case of Cave, we can see a direct line from the beautifully drug-addled mindless violence of The Birthday Party to the world-weariness of his later persona with The Bad Seeds. The road of excess, etc. In a way, The Birthday Party were victims of their own success, forced to live up to a moniker of “The Most Violent Band in Britain” after they relocated to London in 1980. Once established in the UK, they honed their reputation for destruction. After a performance at Manchester’s The Hacienda, they were called “a one band war.” (See a full concert film of that 1982 show just above.)

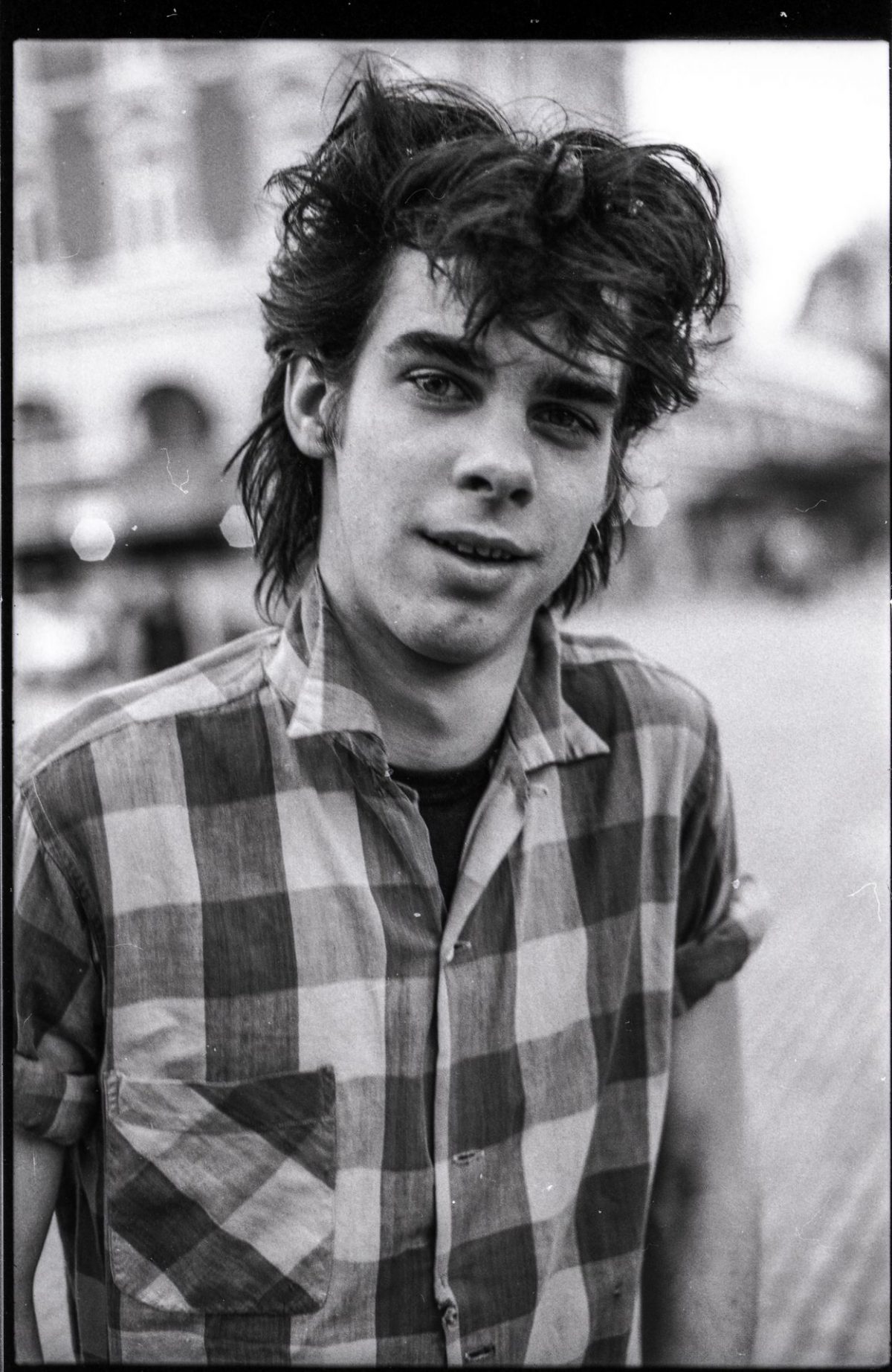

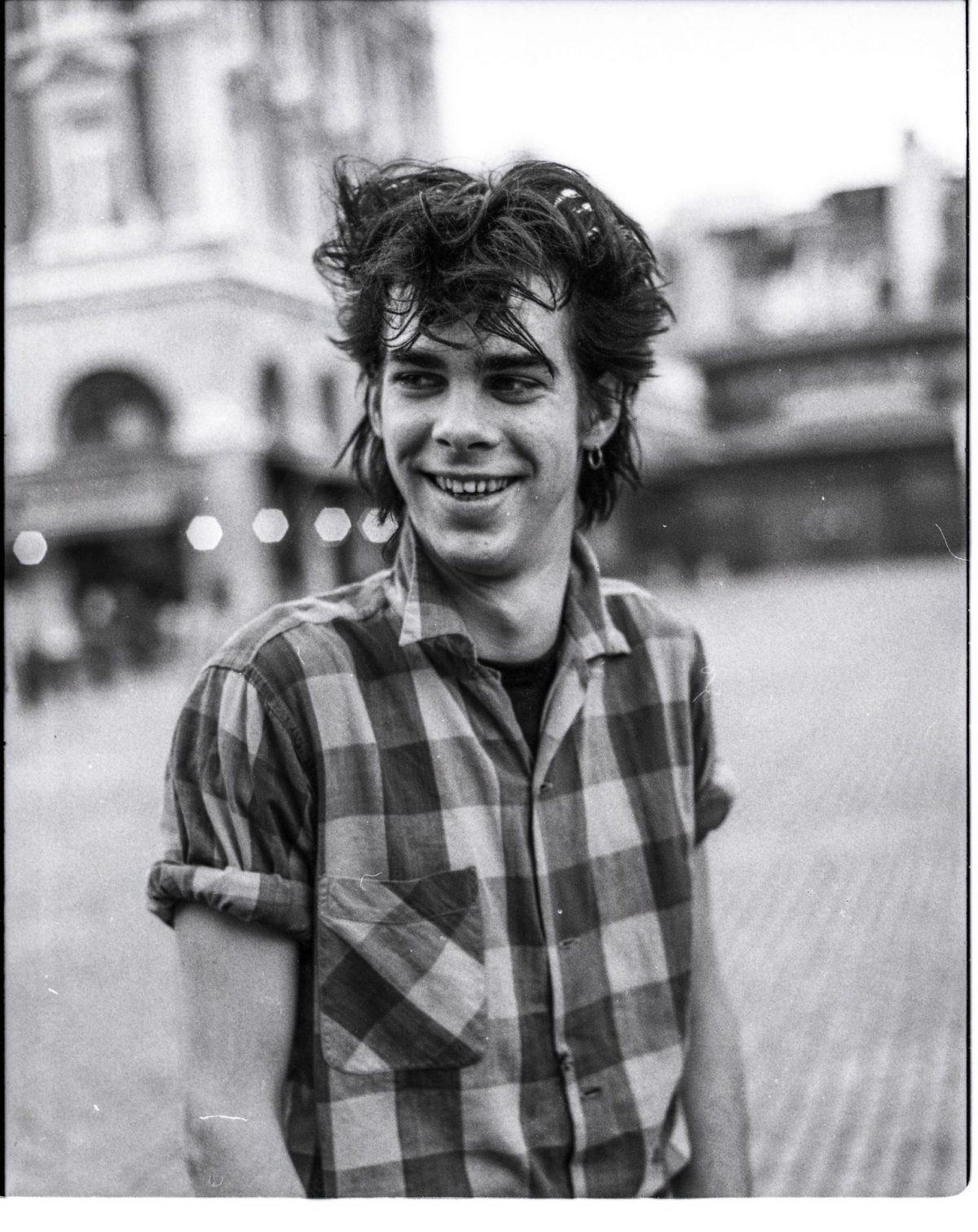

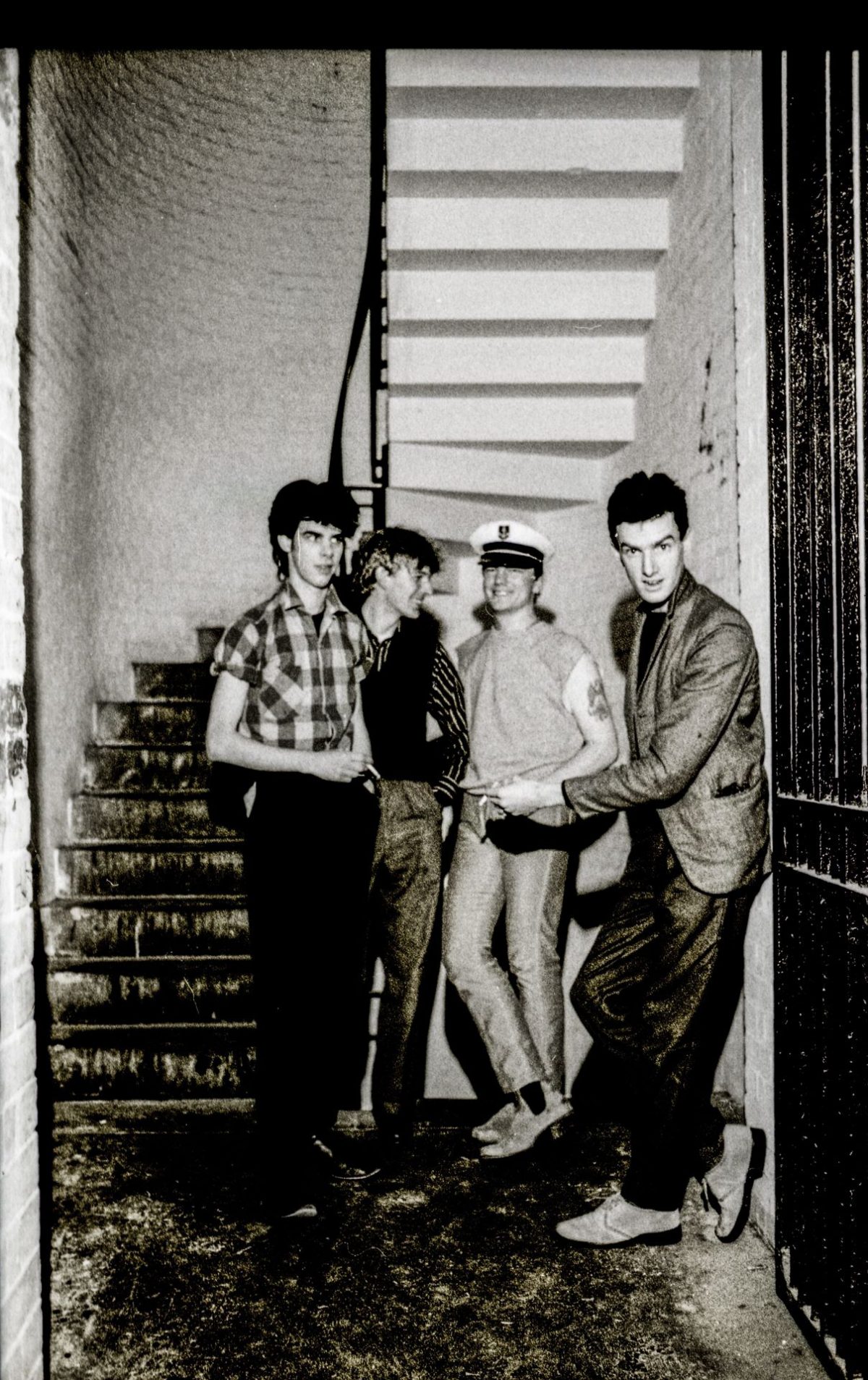

But first came The Boys Next Door in the mid-70s, four “disaffected, dissatisfied teenagers growing up in a middle-class section of Melbourne, listening to hard rockin’ glam acts like the Sensational Alex Harvey Band and Alice Cooper,” as Allmusic notes. Cave would eventually combine these influences with his love of Johnny Cash and Hank Williams and the literary aspirations he nurtured as the son of a literature professor. At first, the new young band was somewhat rudderless. They “quickly found their feet on the back of punk’s ascent,” writes Dave Laing, but “they had yet to find their voice.”

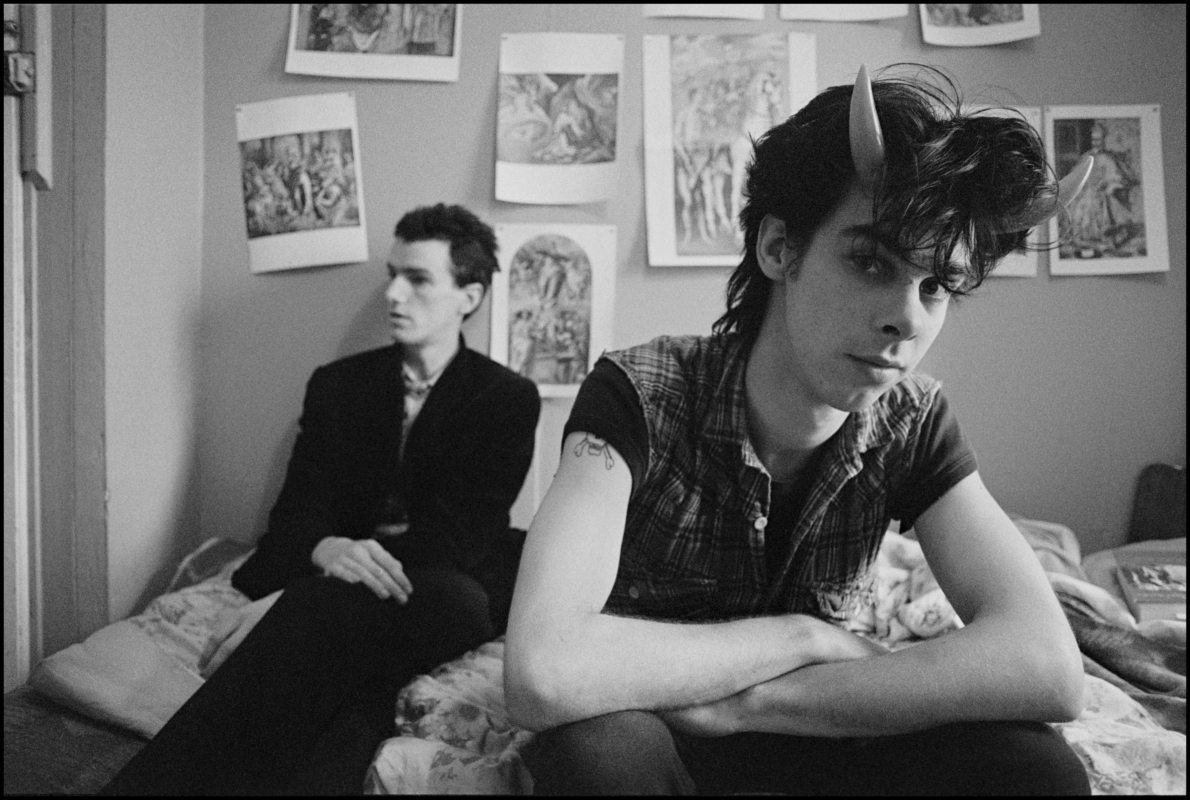

Then came the band’s fifth member in ‘78, guitarist and songwriter Rowland S. Howard, a true original and force to be reckoned with—and probably one of the most underrated musicians in modern rock. He brought with him a song, “Shivers,” from his former band The Young Charlatans. “Howard’s brooding lyrics found a perfect vehicle in Cave’s melodramatic voice,” and the post-punk ballad and its author gave the band its needed direction. “The level of his songwriting forced Nick to up his game,” says Mick Harvey, the only member of the band to survive its collapse and work with Cave in the Bad Seeds. “I would say it’s one of the things that led him to take things more seriously.”

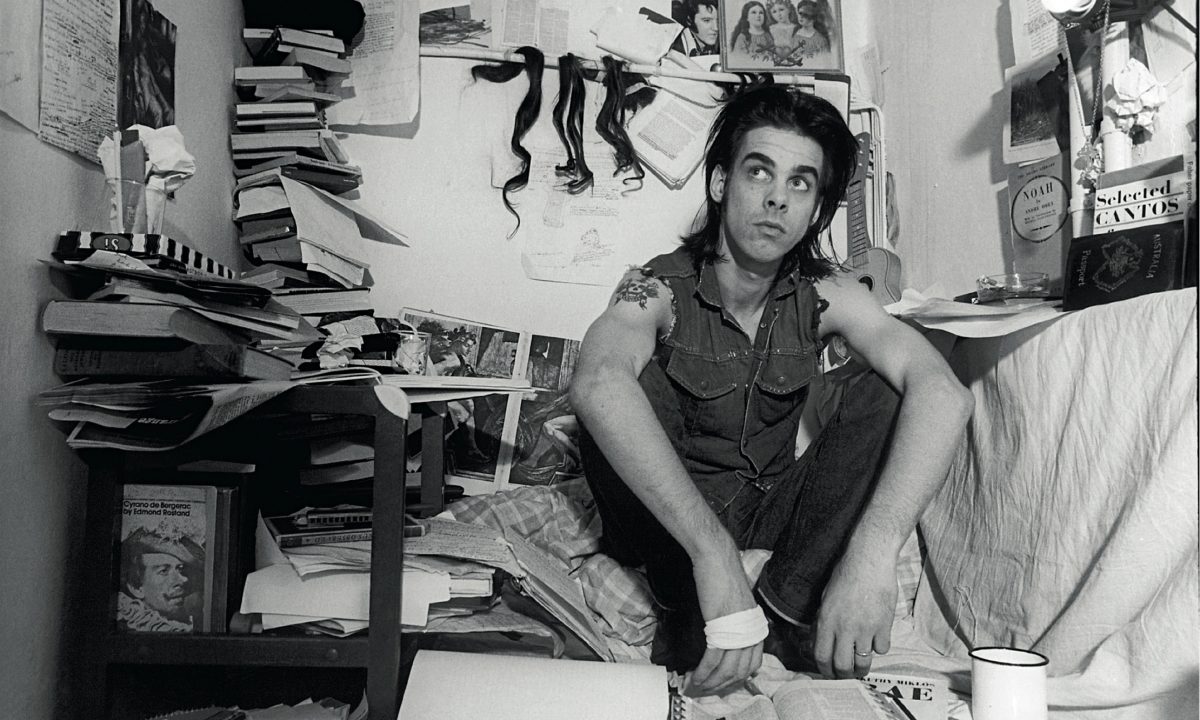

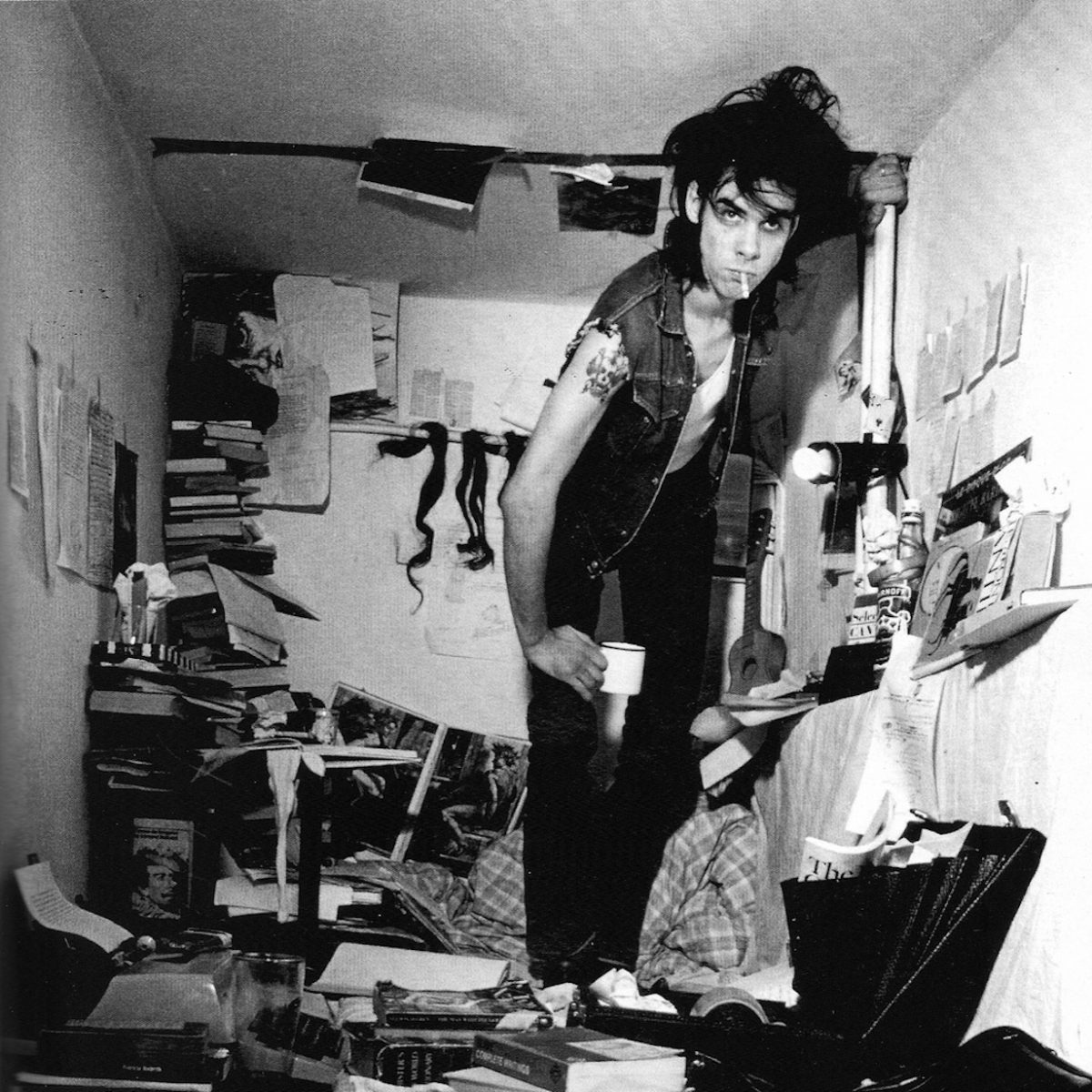

Cave would also credit his and Howard’s friendly competition with The Birthday Party’s demise. The heroin addiction didn’t help, and after a move to Berlin, Cave’s friendship with Blixa Bargeld of industrial pioneers Einstürzende Neubauten turned his head in new directions. A band as brutal and self-destructive as The Birthday Party couldn’t keep it up for long. They were constantly on the edge of complete collapse, which was, of course, central to their appeal.

Bassist Tracy Pew passed away at 28 in 1986. By that time, Cave had already moved on to his new project, and the band that launched his career was in the rearview. In their heyday, however, The Birthday Party were brilliantly terrifying and sublime, described perfectly by Ashley Crawford from a performance at Melbourne’s Crystal Ballroom.

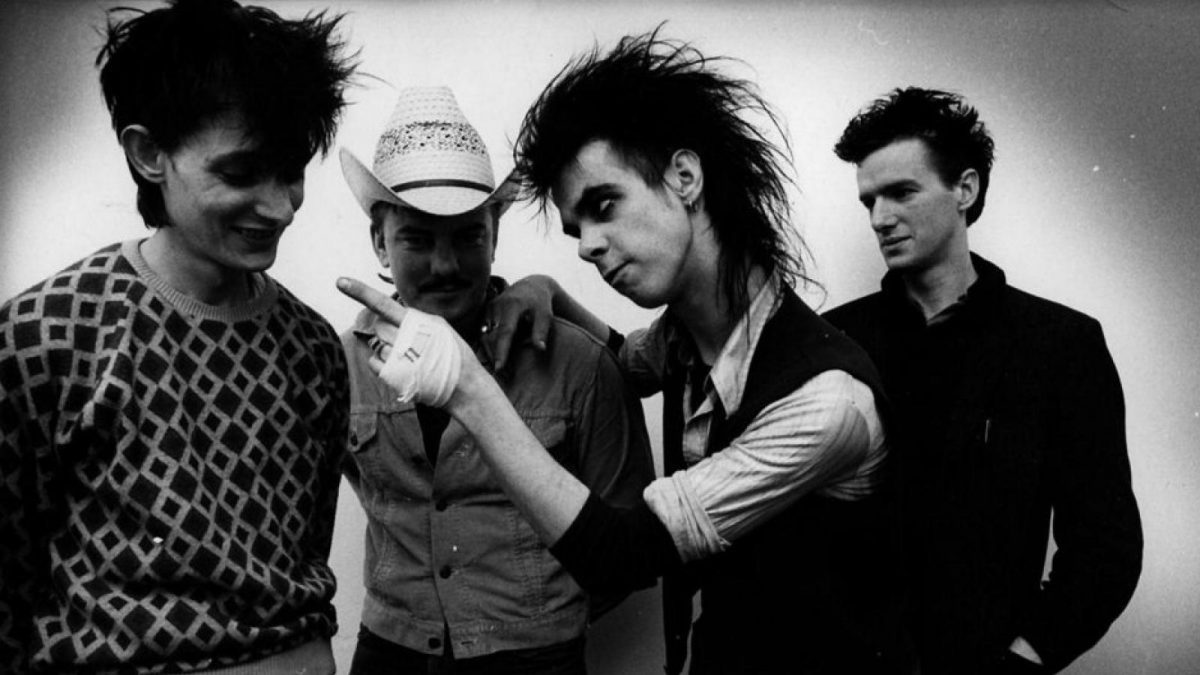

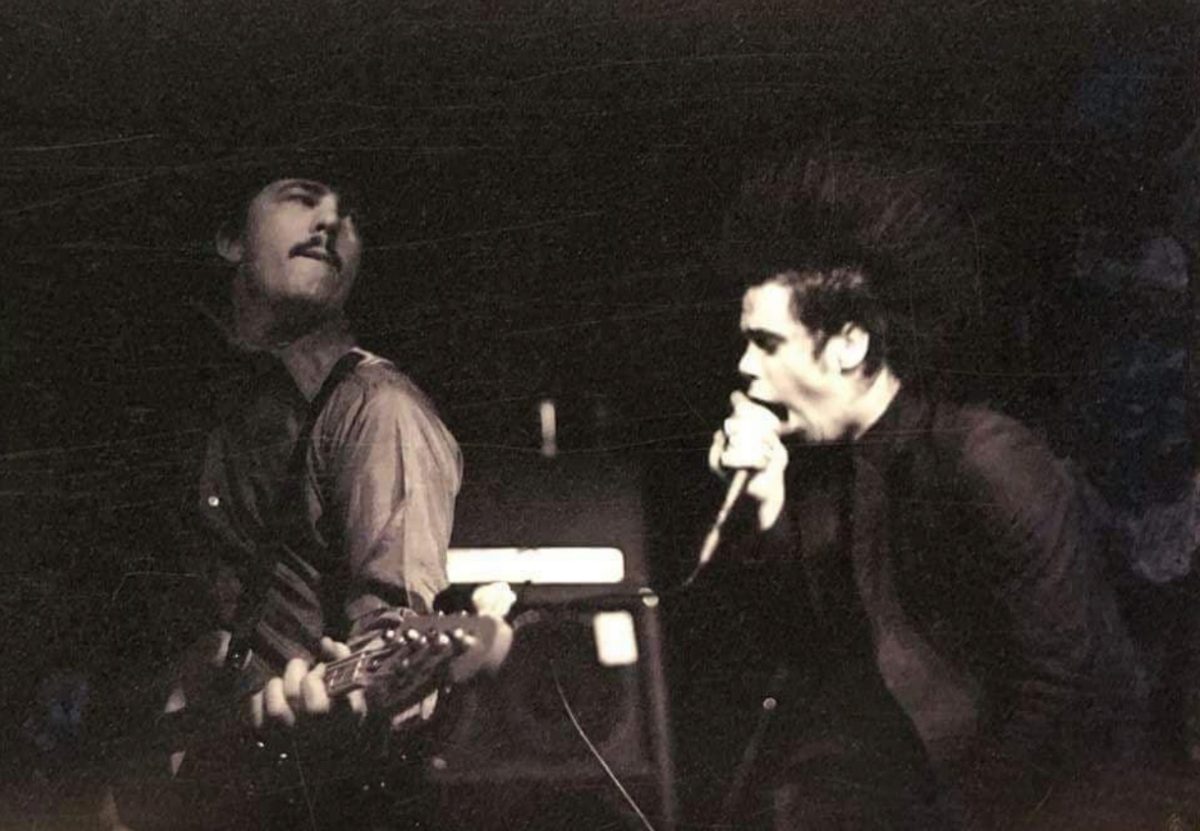

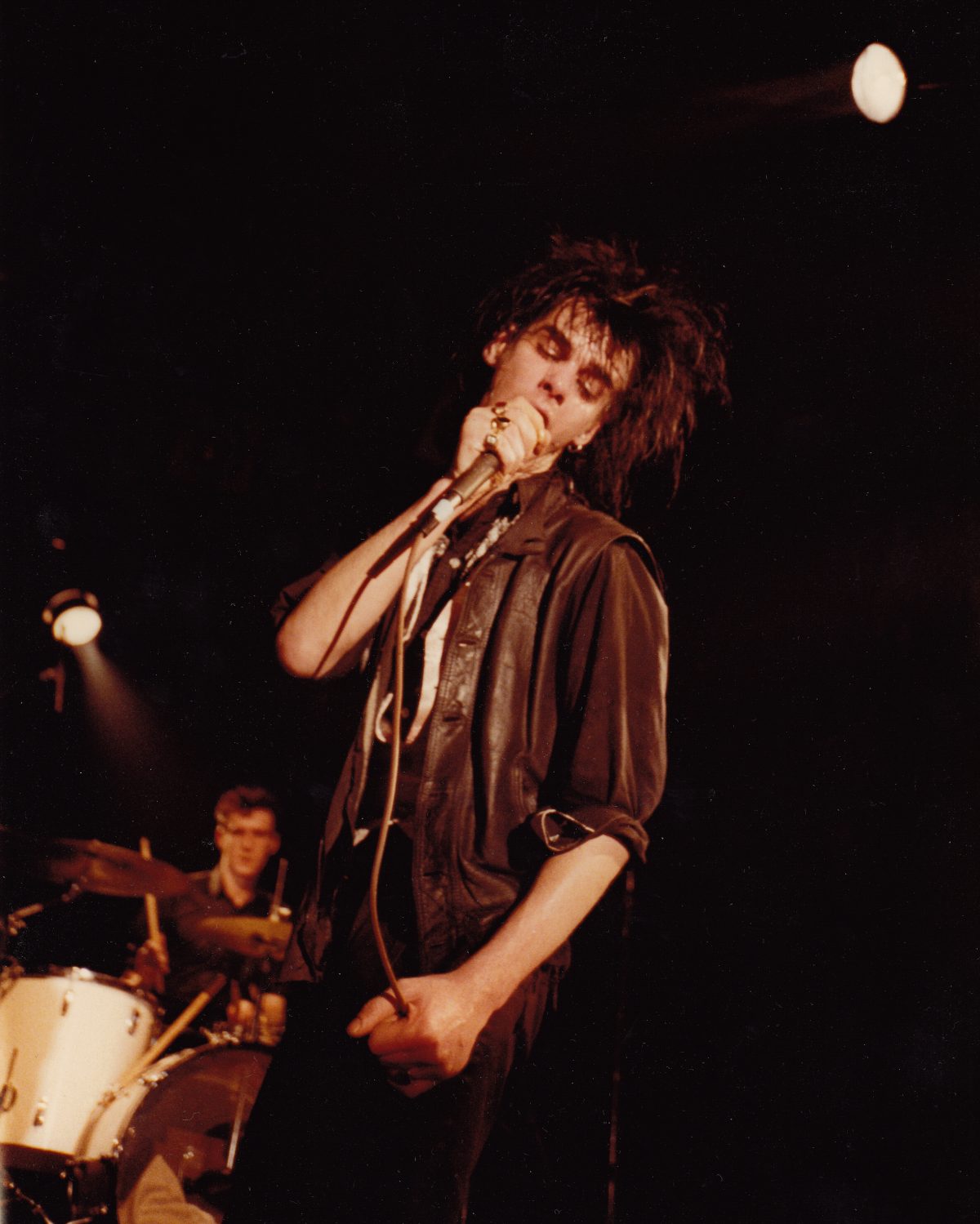

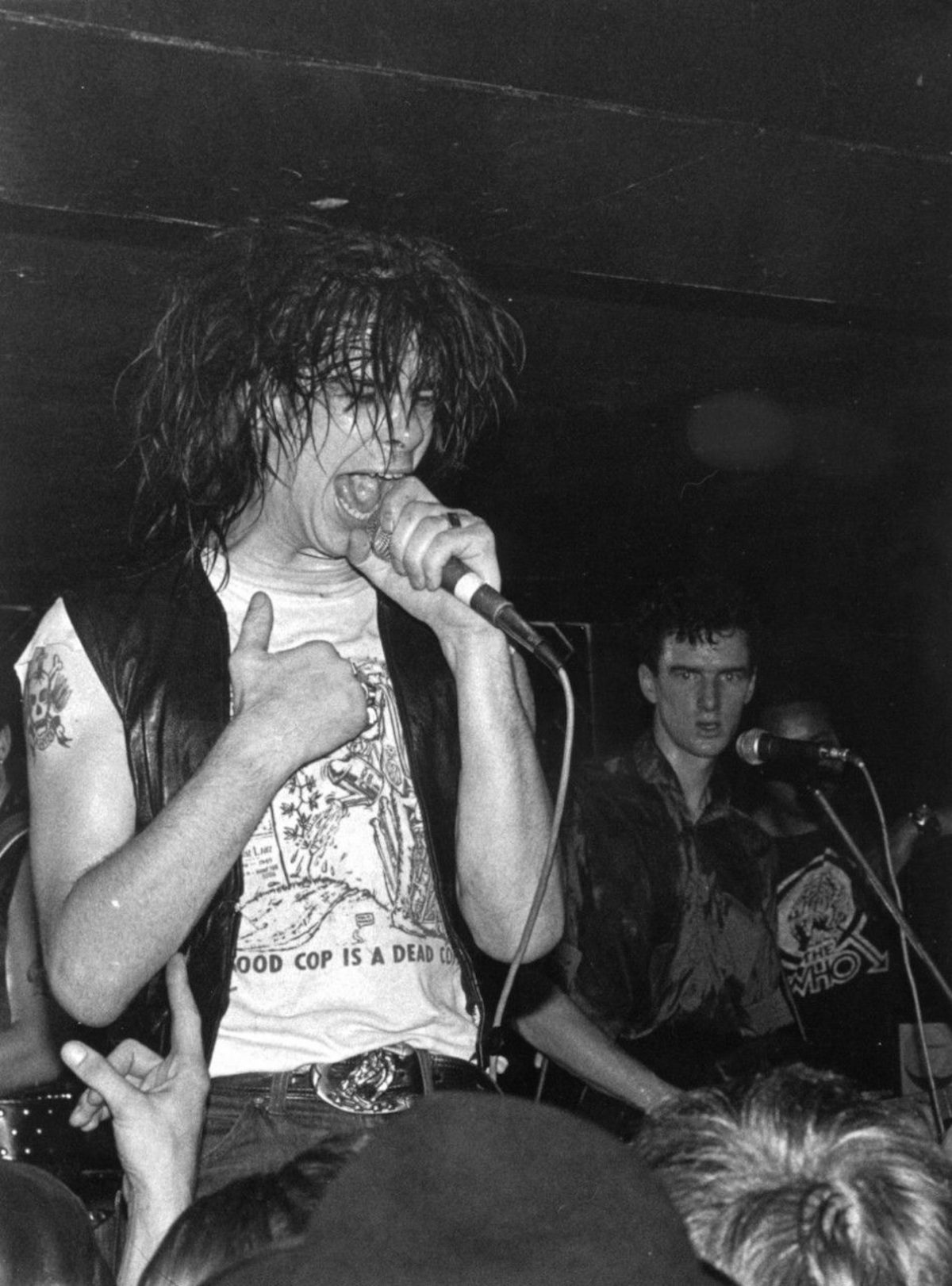

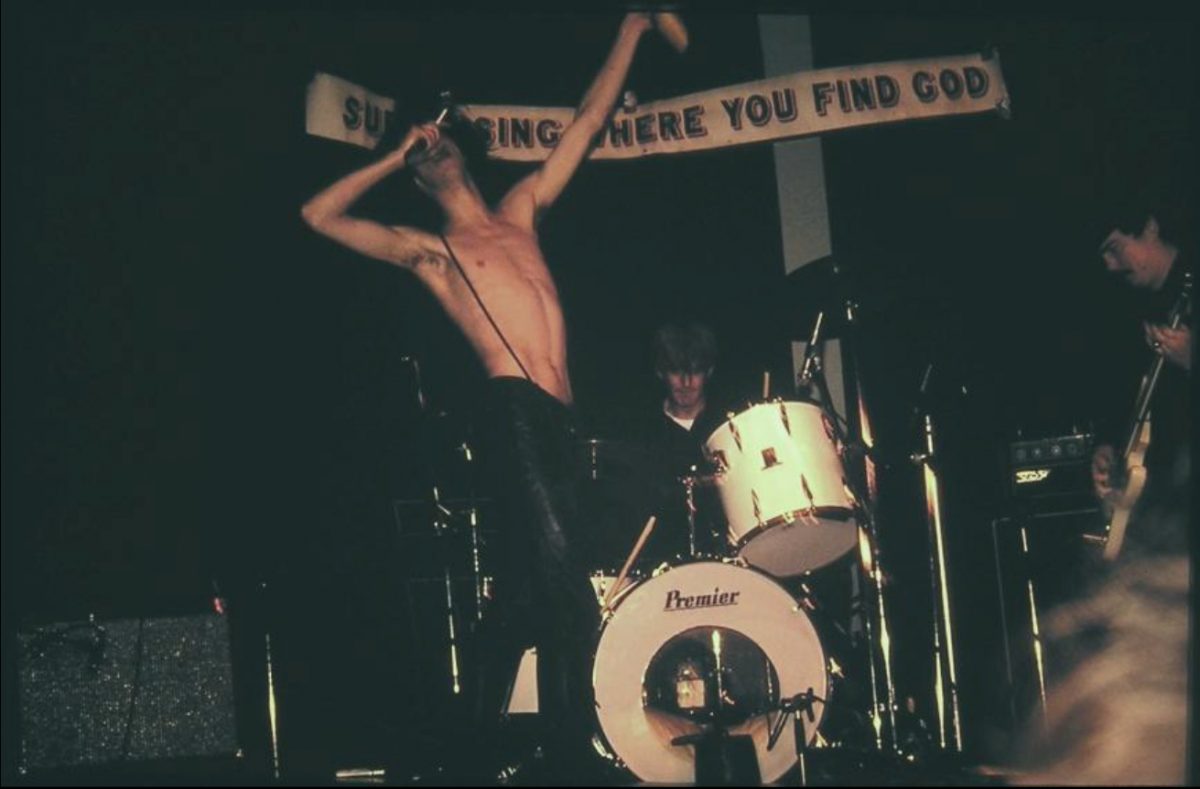

Watching Cave’s band was like rehearsing for entrée into a Hieronymous Bosch painting, a carnivalesque monstrosity of malicious intent and play-time exhibitionism. The still-life elements of this canvas were supplied by the serious intensity of Mick Harvey, who slid into the shadows to the right, hugging his guitar closely, as though to distance himself from the suicidal activities centre stage. The only one who looked part of a more-or-less traditional rock’n’roll band was Tracy Pew, inevitably resplendent in fishnet singlet and ten-gallon Stetson, wielding a bass guitar like an AK47 and known to occasionally stuff his head into the centre of the bass drum as he flailed at his bass guitar.

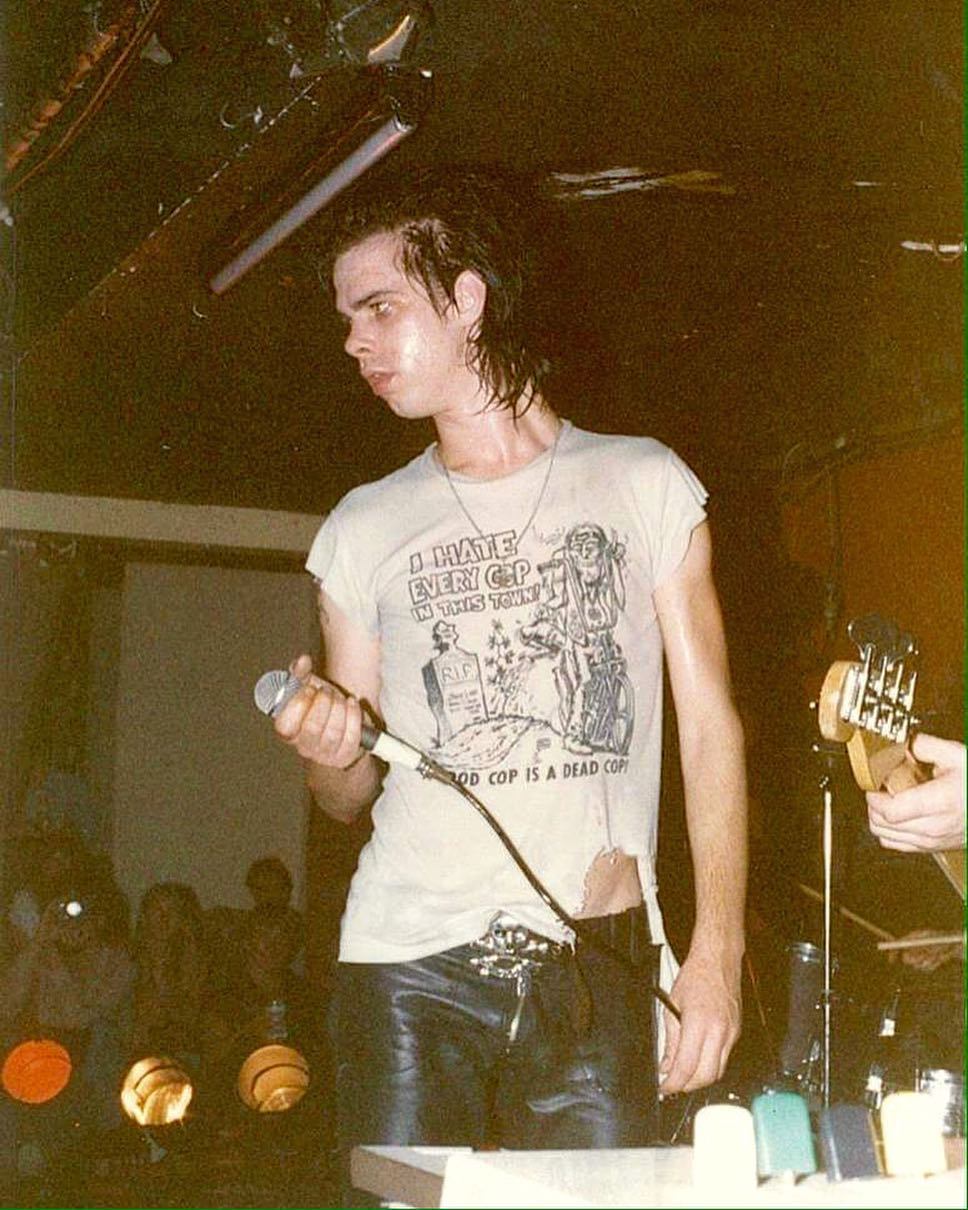

Dominating the stage were two figures. One was Cave, a marionette on amphetamines, an Antonin Artaud performance come to life in 1980s Melbourne. What lights there were would flicker on and Cave would appear, screaming “Who Wants To DIE!?” as drummer Phil Calvert bashed out a crude, militaristic staccato beat. Inevitably to Cave’s right, as though indifferent to the chaos around him, was the sepulchral figure of Roland S. Howard. Even before years of heroin ravagement, Howard was a pale, skeletal figure, his dangling cigarette an extension of sensual, down-turned lips, an eldritch apparition doomed to a half-life while injecting an electrified accompaniment to Cave’s deranged monologues and narratives.

The stories told in these darkened environs were almost inevitably those of despair and darkness, although not without ample helpings of knowing self-mockery. Cave’s later biblical prophesizing was yet to find its genesis. Zoo Music Girl, Nick The Stripper, Release the Bats, King Ink; these were tirades of self-abasement.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.