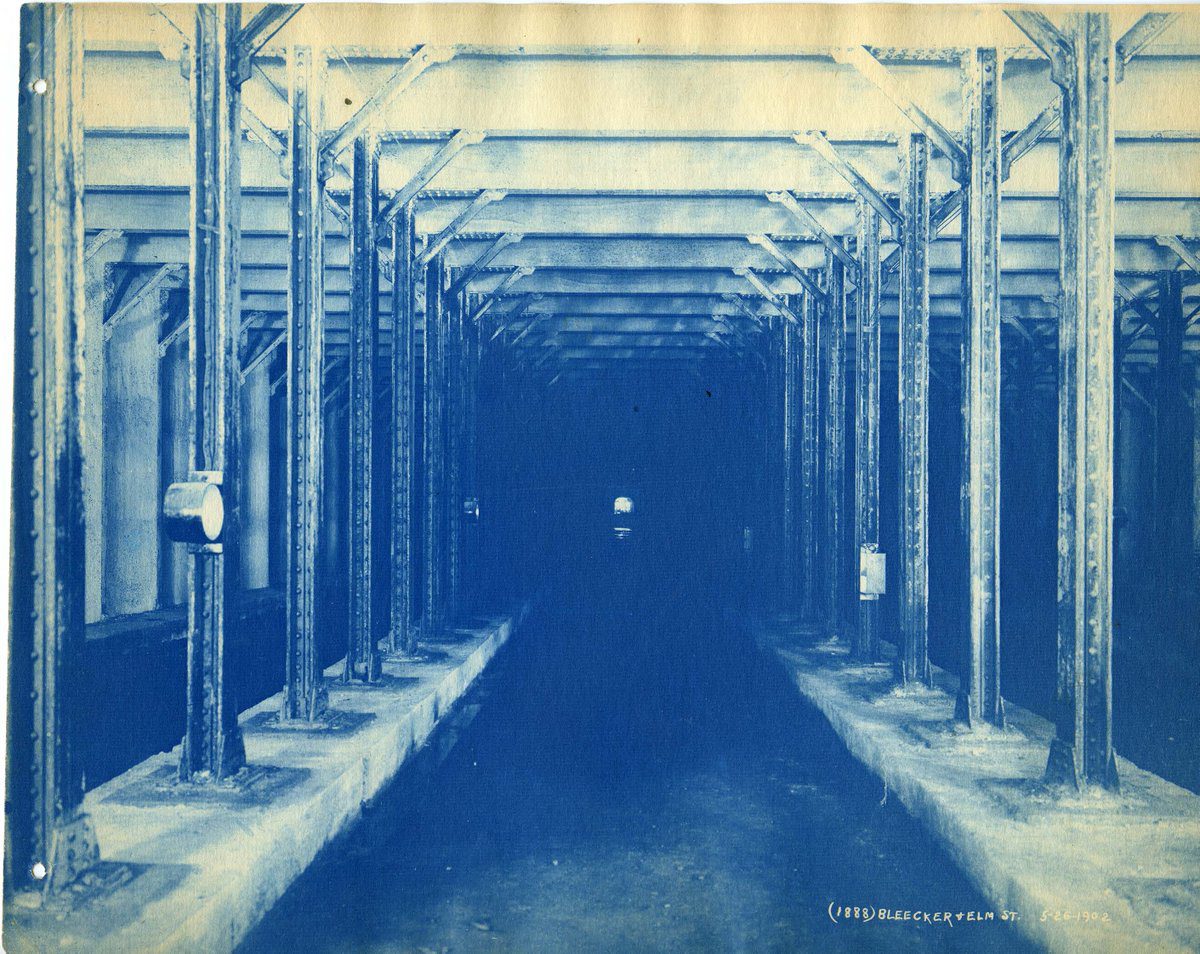

In 1900, contractor Rapid Transit Subway Construction Company “embarked on not only a construction project of unprecedented scope,” writes Christopher Gray at The New York Times, “but also a program of photographic documentation without precursor.” That project was the construction of the New York City subway system, the largest and one of the oldest rapid transit systems in the world. Construction continued for the next forty years (and continues still) as the number of lines expanded under two privately-owned systems, both purchased by the city in 1940.

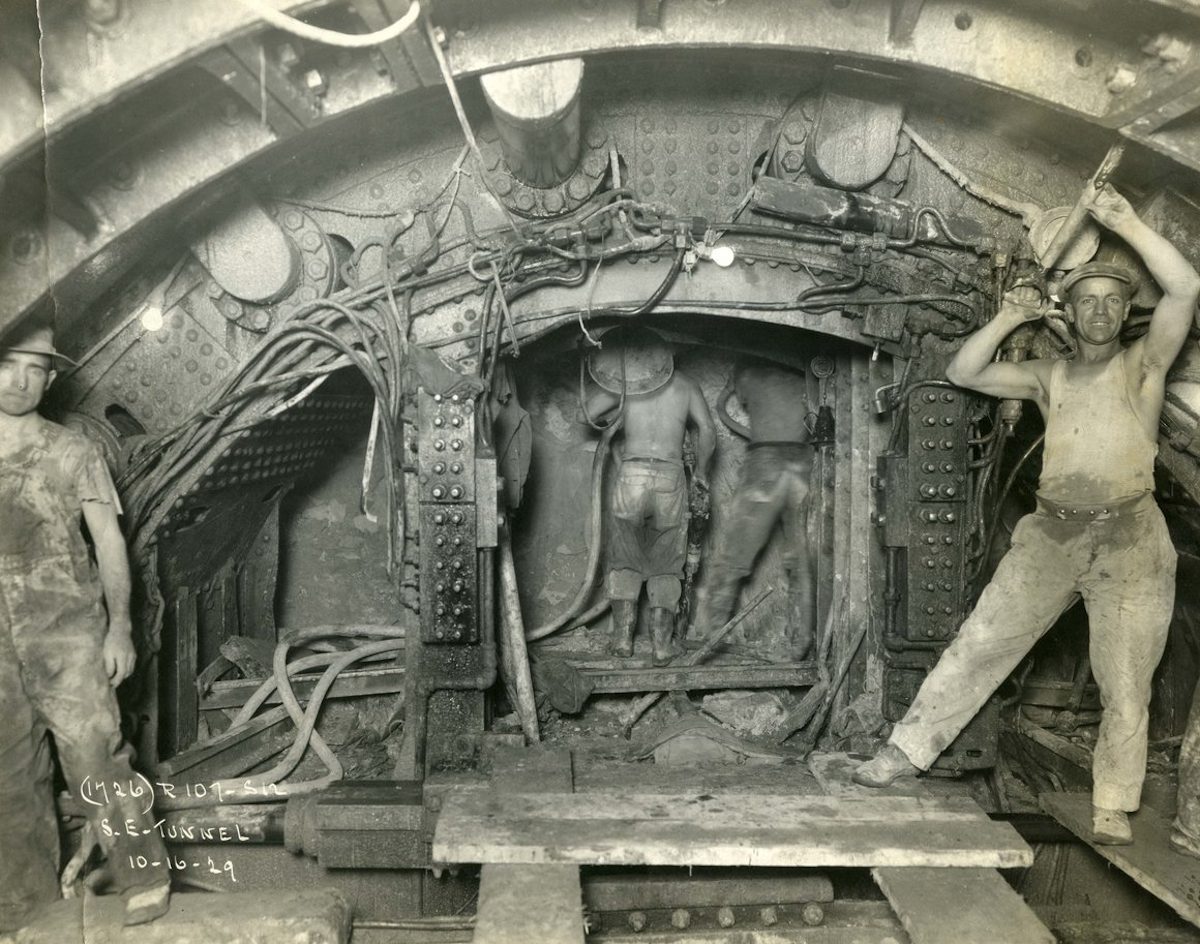

Through it all, two brothers, Pierre and Granville Pullis, and their assistants documented the enormous undertaking in hundreds of thousands of photographs, some of which are on display at the New York Transit Museum until January 2021. “Using cameras with 8-by-10-inch glass negatives,” the brothers “were assigned to record the progress of construction as well as every dislodged flagstone, every cracked brick, every odd building and anything that smelled like a possible lawsuit.” Despite its massive scope and industrial purpose, the Pullis brothers’ project was, for them, much more than a lucrative, extended assignment.

Workers in pump-chamber – The Bronx 1916

9th Street Subway entrance Brooklyn, 1910

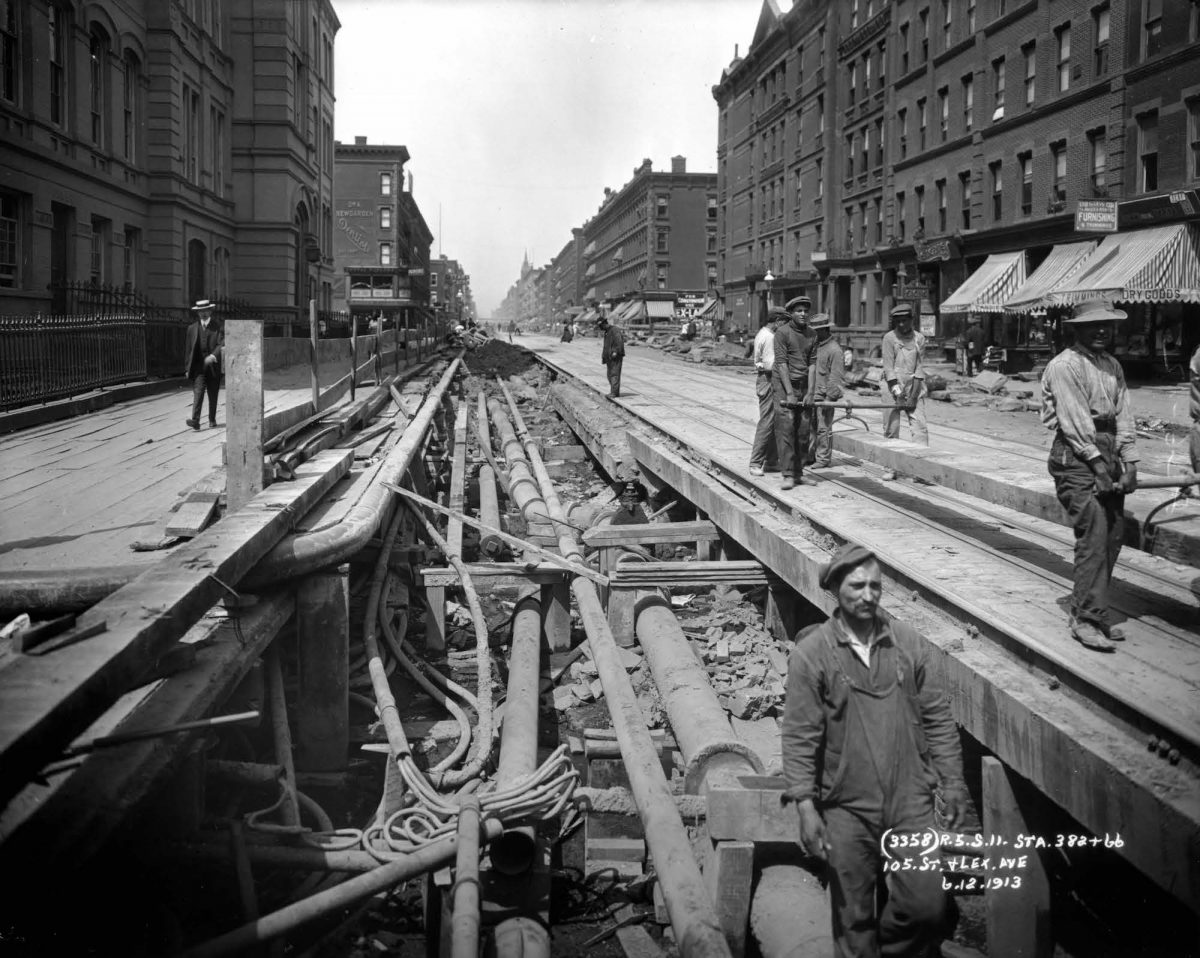

Lexington Avenue between 105th and 106th Streets, Manhattan, 1913

Pierre first served as lead photographer, then his slightly younger brother took over until 1939. The photographers braved some of the same dangers as the workers, and their photos, as The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported as early as 1901, “are as interesting as they are difficult to obtain. In many cases, Mr. Pullis and his assistants are obliged to place their cameras in perilous positions in order to photograph the face of a rock or the effect of a blast, and taking flashlight pictures knee deep in a twenty-five foot sewer.” They meticulously documented a rapidly changing urban landscape, both above and below street level.

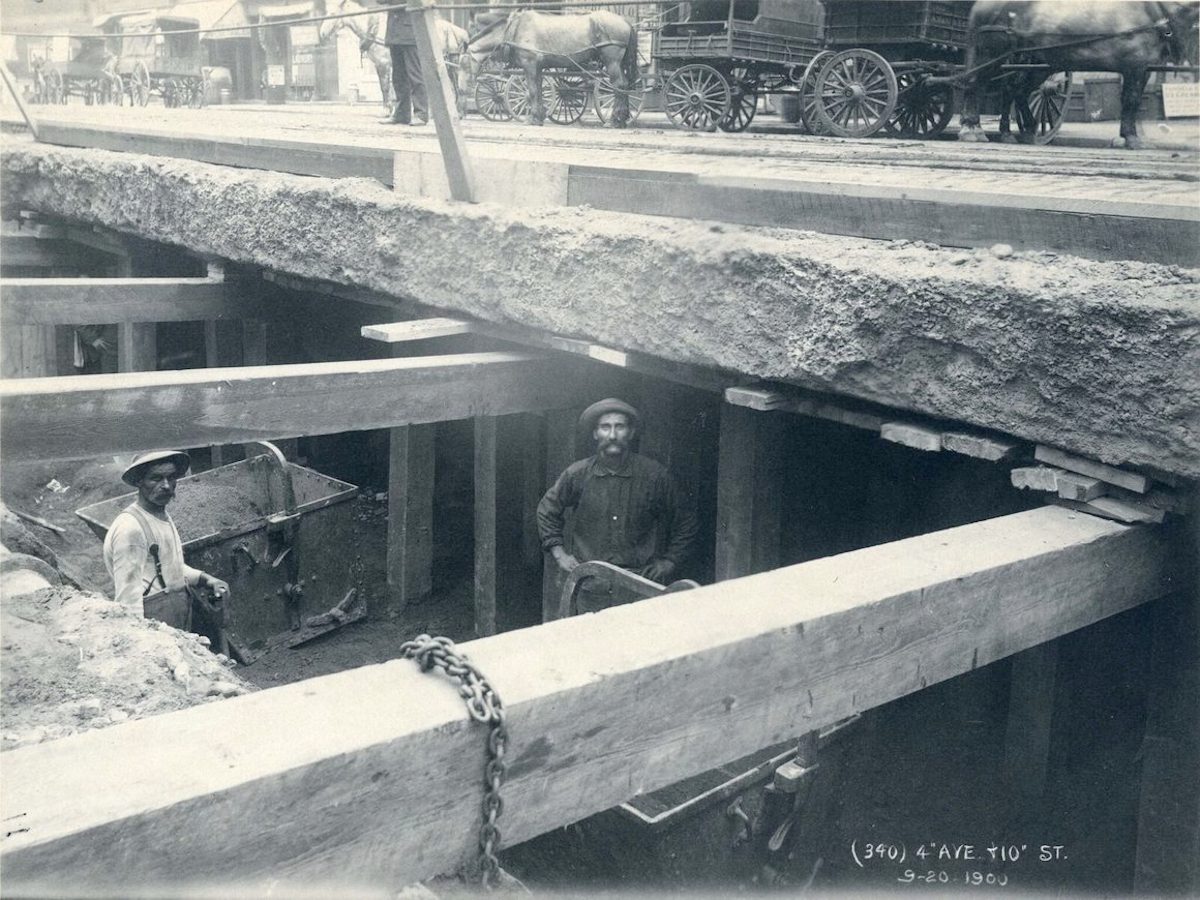

Perhaps of interest to most viewers today, the photos also humanize the mostly anonymous workers, showing them in relaxed, unguarded, and unscripted poses. They create a sense of intimacy over the distance of a hundred years and more, as we gaze at streets dominated by horses and carriages while a vast, modern transit system takes shape underground. “A lot of the people in these photographs, we’ll never know their names,” says Jodi Shapiro, curator of the Transit Museum exhibit. “But we know their faces. That’s our privilege—to let people know, these are the people that built this. Somebody photographed them and cared enough about them to make them look dignified in their work.”

As fascinating as these faces are, so too are the cityscapes, and landscapes, of a developing New York the photographers captured over the course of decades. One 1903 image of Lafayette Street, Gray writes, “looked like a city after a bombing, gaunt hummocks of earth and debris.” A 1908 photo of West End Avenue uptown “is almost sleepy: a collie-type dog, brown or black with splash of white around its neck, wanders across the street, not a vehicle in sight.”

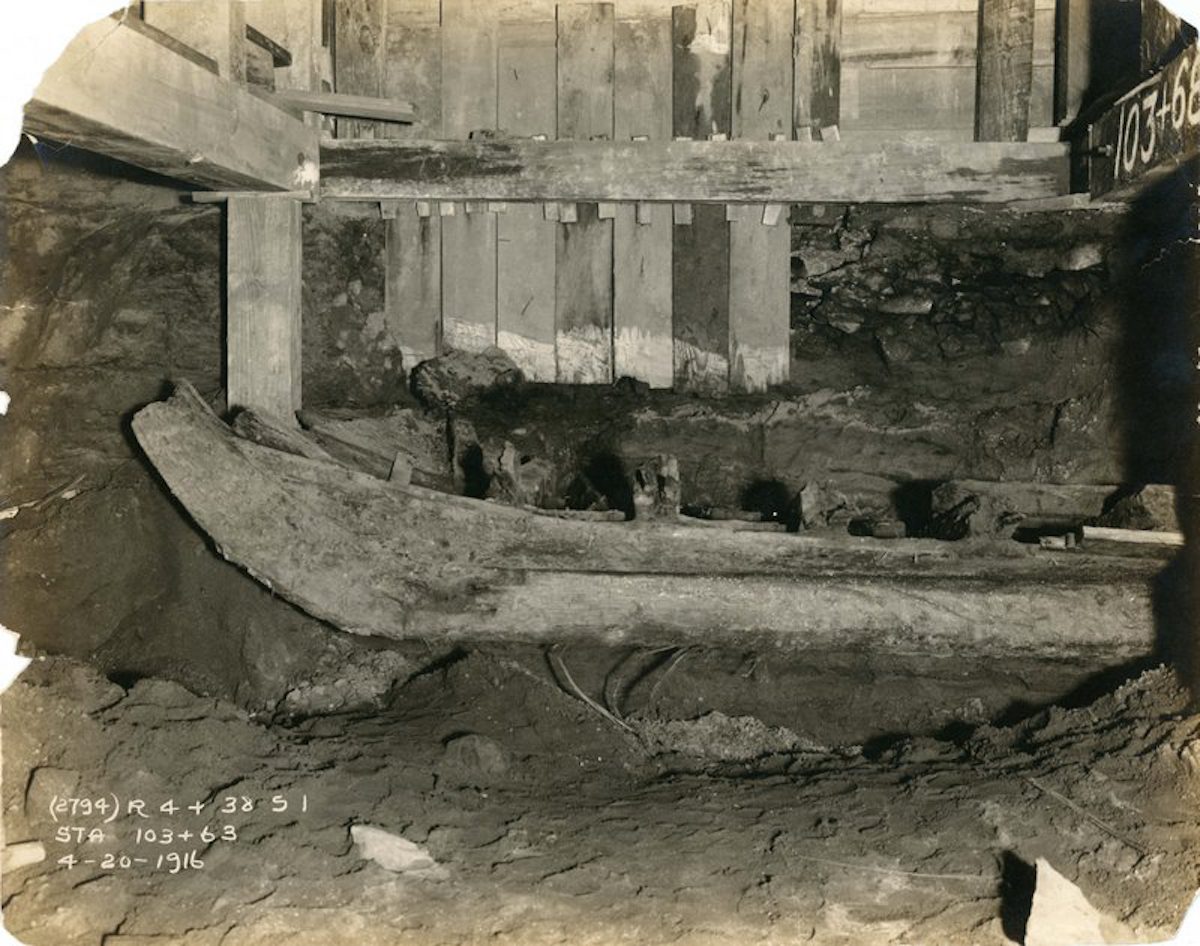

Because of their commitment to documenting the entire construction process, the brothers returned to the same locations over and over again, inadvertently chronicling the outer boroughs and far uptown locations shift from semi-rural and small maritime communities to architecturally dense urban environments. They also documented excavated artifacts from the city’s many strata of inhabitants.

Many of the photos were bound in books, and some on display have holes punched in them. There is no central catalogue, though all the negatives are inscribed with dates, numbers, and locations. The thousands of prints and negatives are scattered throughout collections around the city, with the New York Historical Society holding at least 65,000 images. Fully immersing oneself in these photos isn’t just taking a trip back in time, it’s traveling through it, watching New York acquire its most essential, and iconic, infrastructure network, day by day and year by year.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.