“One that I will enjoy, the true story of my sex life, my excessive desire to continue melting the ice of American hypocrisy regarding behaviour and beliefs that are now ‘in the closet’ and only surface in court, crime, or comical conversation.”

– Chuck Berry

“And Janice, how old are you?” the US Attorney asked Janice Escalanti, at the start of Chuck Berry’s trial. “Fourteen years old,” she said, quietly. It was her quietness that first appealed to Berry.

The attorney often had to ask Escalanti to speak louder, to clarify, to repeat what Berry had said to her, word for word. Her answers edged forward in whispered “yes, sirs” and “no, sirs.” She didn’t look fourteen, the attorney thought, but the more she talked, the younger she seemed.

Berry looked at Escalanti. She was, he wrote in his autobiography, “the spitting image of a teenage photo of my mother’s younger sister, Aunt Alice, with an olive complexion, pie face, and stout, high cheek bones.” According to Berry’s lawyer, speaking to Berry’s biographer, she was “very, very homely” and “not very pretty at all. And that’s why I believe Chuck.”

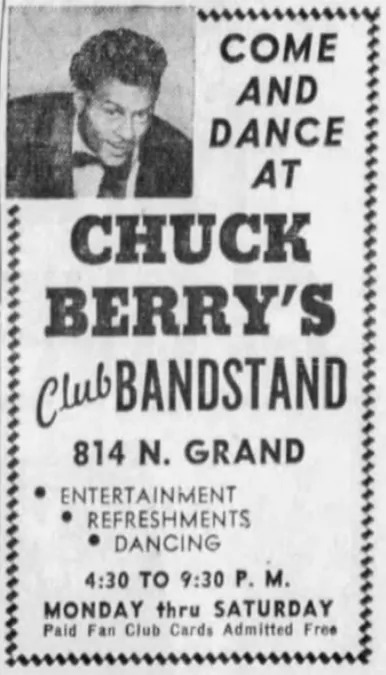

Berry and Escalanti agreed about the general outline of events: they had met in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, in December 1959, and travelled together for a week, through five states, to St Louis. Escalanti worked for Berry for ten days in a club that he owned in the city, Club Bandstand.

The question for these lawyers, for the judge, for the jury, was why Berry had brought Escalanti this far from home. Did Berry rape her on their journey, in hotel rooms en route, in the back seat of his Cadillac while his pianist drove and his band slept, and in a house he owned in St Louis?

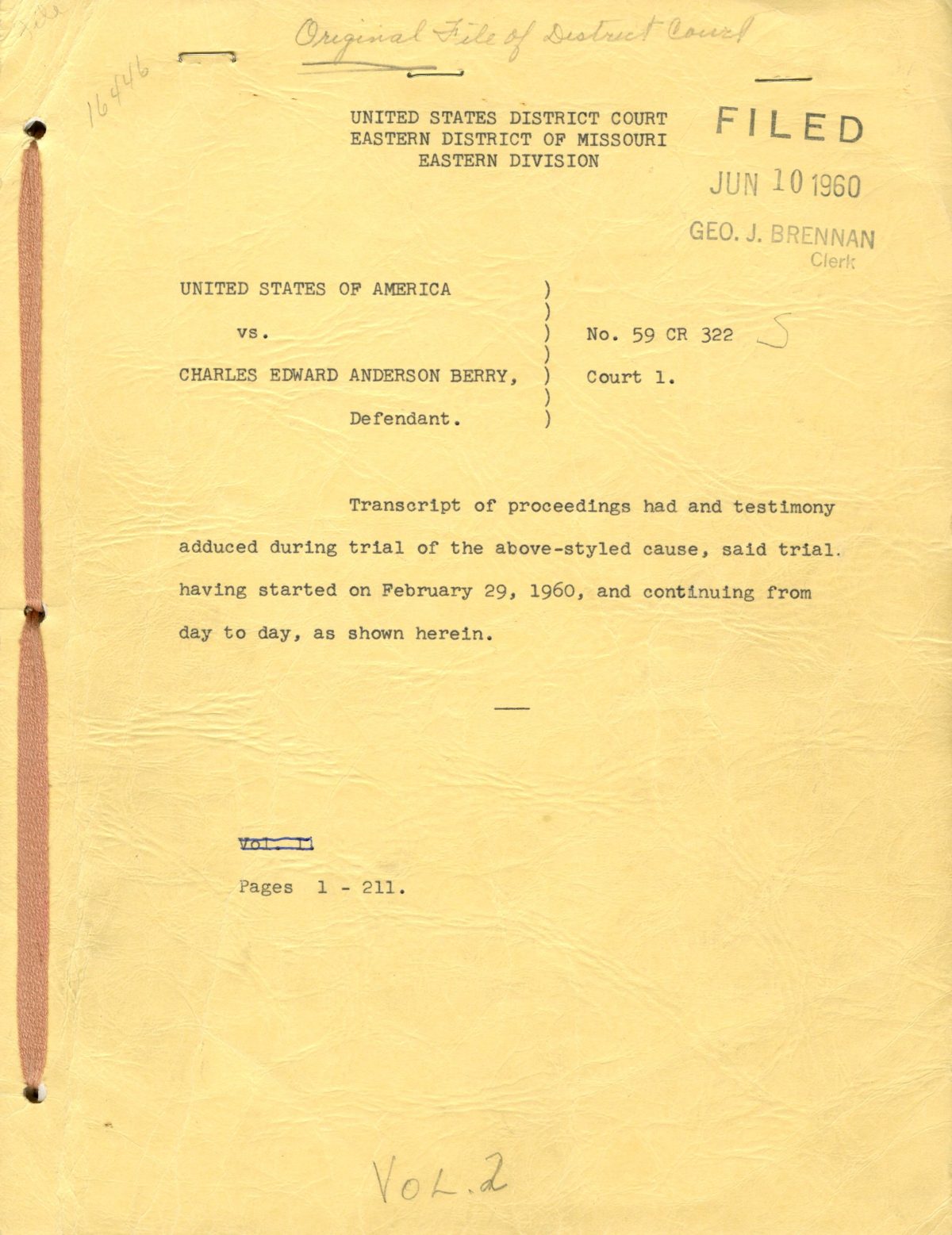

As the allegations crossed state lines, and the law prohibiting sex with minors was then only at a state rather than a federal level, the US Attorney charged Berry under the Mann Act, sometimes known as the White Slavery Act.

The Act was both notorious and broadly drafted, used as much to target consensual non-marital relationships, particularly relationships between black men and white women, as sex-trafficking and abuse. The attorney explained to the jury that, under the Act, the question was whether Berry had “transported a woman, or a girl, across state lines for the purposes of immoral practices or debauchery.”

This language had two contradictory consequences for Berry. Firstly, during the trial, it meant that the attorney did not have to prove that Berry had actually sexually abused or raped Escalanti, or even what he knew or did not know about her age, merely that his intent was “immoral.” As there was certainly “transportation,” although there were questions about whether he had raped her and whether he knee she was fourteen the focus was on his perceived motives rather than what happened. This likely made it easier to charge him.

Secondly though, in the longer term, the language has seemingly helped protect Berry’s reputation. Both then and now, press coverage of Berry tends to use the Mann Act language, if the trial is mentioned at all. Just as the broad legal language allowed racist prosecutors and judges to use the Act to target consensual relationships, it also means the specifics of what Berry was alleged to have done are lost. Rather than the language of “child sexual abuse” or “rape” that would likely be used if he was charged today given Escalanti’s age, he is described as “transporting” her. Even where that press coverage discusses Berry’s “immoral” intent, what actually happened to Escalanti beyond that “transportation” is too often missed.

Chuck Berry Fan Club membership card (Source- Elvis Echoes of the Past)

Berry was familiar with trials and court rooms, with white men asking questions. When he was eighteen, he was convicted of armed robbery and served three years in prison, where he first started writing music. Three months before he met Escalanti, in late summer 1959, he was charged with “disorderly conduct” after a white girl in Mississippi told police he had asked her for a “date.”

Even now, during this “Indian trial,” as he called it, he was awaiting two further trials. One, which he called “the French trial” due to the victim’s French ancestry, was another Mann Act charge, involving “transporting” seventeen year old Joan Mathis Bates back in summer 1958; the US Attorney had told him then that he would only face the charges if there was another similar incident. The other trial was for carrying a firearm over state lines as a convicted felon; the patrolman who found Mathis Bates in Berry’s peach Cadillac also found a loaded automatic pistol under the driver’s seat.

“I decided to take a happy go lucky view of it all,” Berry wrote in his autobiography. Occasionally, while listening to witness testimony during the Escalanti trial, he took a copy of Time magazine from his pocket and read through. There was an image of Pat Nixon on the cover, staring serenely out of a window.

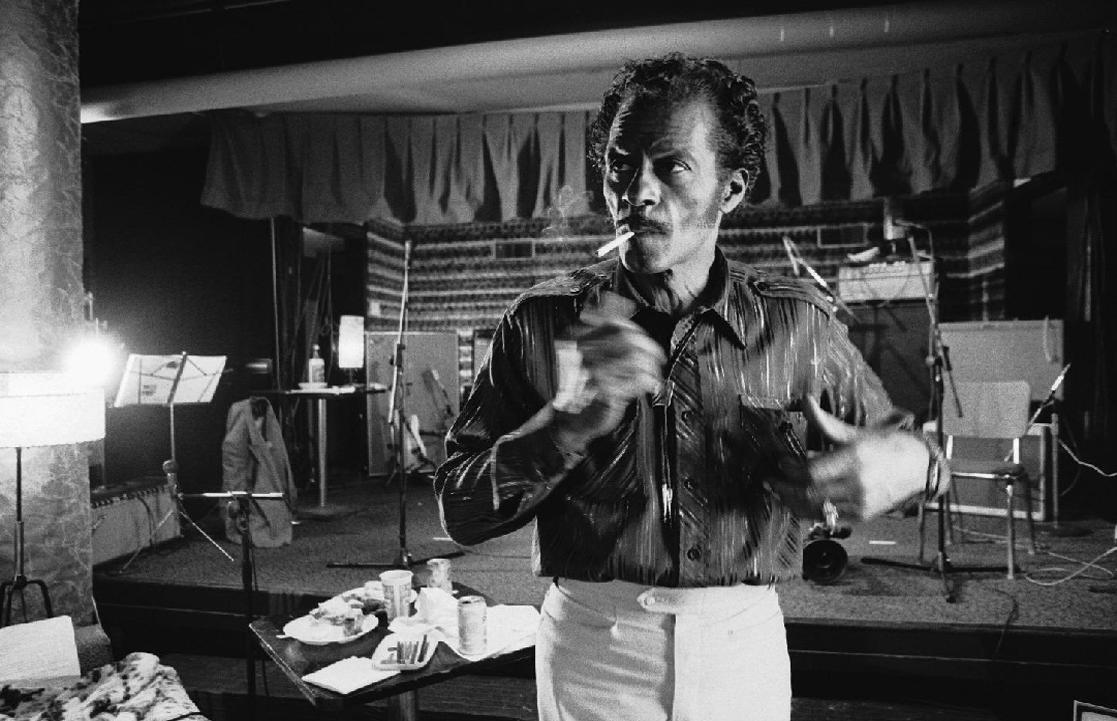

Terry O’Neill, Chuck Berry, St Louis

From the stand, with Berry watching, Escalanti told the attorney that she had lived in Mescalero, New Mexico, with her mother, before this all began. She was three-quarters Mescalero Apache, she said, and one quarter Yuma, and lived on the reservation. She had had lived in Yuma, Arizona, too, for a while, with her father. The judge, an elderly white man who complained frequently about some unspecified pain, called her “this Indian girl.” He called Berry “this Negro,” slurring it to make it sound like “nigger.”

Escalanti didn’t like school, she said. She got up to eighth grade, at Mescalero Indian School. She didn’t do well. They asked her to repeat a year. In March 1959, she left town.

She went to Ciudad Juarez, where she lived with a cousin, and then over the river into El Paso, Texas. In El Paso, she said, she was arrested three times. Once, it was for vagrancy, once for drunkenness, once for prostitution. Sometimes she forgot how often she had been in jail. She told the court that had worked as a prostitute since she was thirteen, back in Mescalero.

Once, she said, haltingly, quietly, in El Paso, “I got drunk and… got put in jail… about 25 days.” The day she got out, 1st December 1959, a brother of a guy she had worked for asked her to do waitressing at his club. It was called the De Luxe. She worked there for a few hours. Another guy came and gave her ten dollars, she said, although she didn’t say why. It was quiet at the club. The owner told her to come back later, to stay through the night.

She left the De Luxe with the ten dollars, and went “out drinking,” over the bridge into Mexico, to Juarez. She went to a bar, the Savoy. Berry walked in. She recognised him from TV, from his records, from his pictures in magazines, from a movie.

Berry and his band had come into Juarez that afternoon. “We spent some hours stopping at different strip joints,” he wrote, “watching the girls.” They ended up at the Savoy, “a cantina,” Berry called it. Another guy that Escalanti knew asked her to speak to Berry, to show him around Juarez.

Escalanti introduced herself as “Heba Norine,” her “Indian name.” “I was born under Janice,” she said, “but I was named Heba as an Indian girl.” Berry began “talking music and stuff,” he said, with Escalanti and a friend of hers. Escalanti “was saying little but agreeing to everything by nodding her head,” he remembered. He liked it. He asked her how old she was. “She shrugged her shoulders,” he wrote in his autobiography. Her friend told him that Escalanti was twenty one.

The attorney asked Escalanti if she saw Berry here, in the courtroom.

“Yes, I do.”

“Will you point him out, please?”

“Right there.”

They left the bar, and met Berry’s band outside, “his men, his boys,” Escalanti said: Johnnie Johnson, his pianist; Jasper Thomas, his drummer; Leroy Davis, his sax player.

Davis was leaning on Berry’s car, a red 1958 Cadillac. It had two chrome air horns on the passenger side. There was a poster in the back window, with Berry’s name and a picture of him carrying his guitar.

At the trial, Berry denied he had any “immoral” motives when he invited Escalanti into his Cadillac for the first time. However, in his autobiography, published in the nineteen eighties, he admitted that he often “allowed the band members to take a girl along to the next town if they wanted to go. The fact was that I had fancied doing likewise myself and could hardly set up a rule for them that I, myself, did not care to practice.”

Berry drove them around for two or three hours. Davis and Thomas were in the back seat. Johnson was in the front, with Escalanti between him and Berry. Escalanti pointed out the city’s sights, “the bars, the clubs, the bars, the bull rings, and different things,” she said. The band were impressed with the clubs built with stone brought down from the mountains. Escalanti knew the city, and the language. “They wanted to know where the places were, how much houses around there would cost,” she said, these professional men in their thirties, with wives and children and houses of their own. They drove to the edge of the city, to “the second to the last bar in Juarez,” Escalanti told the attorney.

Berry began speaking to Escalanti in Spanish. He told her he had an interest in the culture, in the language, that he wanted to perfect it, that he had recorded songs in Spanish. “The general trend now in recordings is to sing in native tongues,” he said.

At some point, they stopped for dinner. Escalanti said that she wanted to go to the gig that Berry was due to play in El Paso that night, to “the dance,” as she called it. “Chuck asked me if I wanted to go back across the bridge with him,” she said. “The Rio Grande River, right across the bridge.”

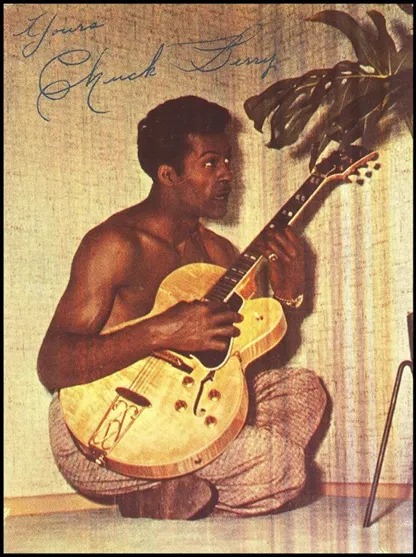

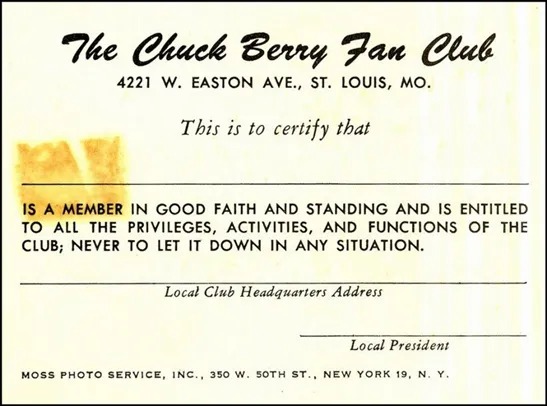

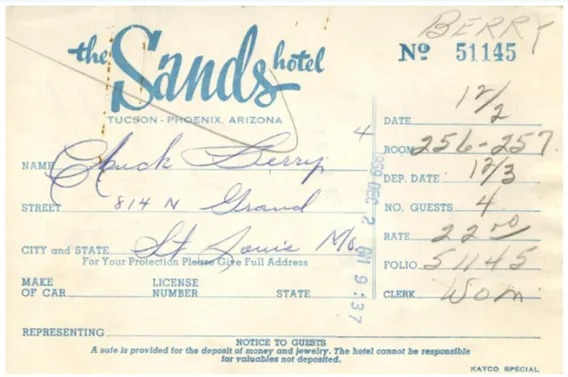

Berry gave Escalanti a membership card to his fan club. It had a picture of him on the front, sat topless, playing his guitar. He autographed it. There was an address in St Louis on the other side, the fan club’s headquarters. There was a promise, that the a member of the fan club had to sign, “never to let it down in any situation.” Berry often kept spare fan cards in his pocket. He had one with him in his pocket during the trial.

“Sometimes we never see these members,” he said, “it is just the idea of belonging… a fan club is just sort of, to know that you are near or associating with the artists that you like, or that you are fond of.”

Escalanti kept her card, until she handed it to the US Attorney, preparing for the trial. It was entered into evidence, marked Government Exhibit Number 6.

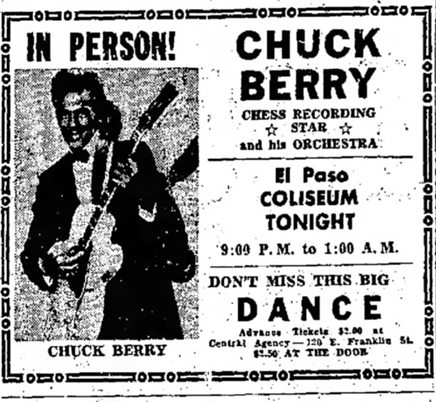

After dinner, they drove to the Coliseum in El Paso, the venue for the night’s show. Berry, Davis, Thomas and Johnson got out to set up. Escalanti stayed in the car, waiting alone, drunk. The Coliseum wasn’t often used as a concert venue. It had recently been frozen for the Ice Capades, and had hosted a dog obedience show. There was a beauty show coming soon.

Advertisement for Berry’s show in El Paso (Source: El Paso Herald-Post, 1st December 1959)

After about half an hour, Berry came back. Escalanti said she wanted to see him play, but had no money. Berry said she could sell pictures for him, he said, so “she could get into the dance and see the show as an employee.” However, he told her that her appearance “was not what it should be.”

He drove Escalanti to another club, the Black and Tan, where a friend of hers worked. Escalanti had been keeping her things at the friend’s house, while she was in prison. The friend wasn’t there. Escalanti didn’t know where the friend lived. She had moved while Escalanti was locked up.

Waiting in the Cadillac, Berry asked Escalanti about her age again, as he had at the bar in Juarez. She told him that she was twenty-one. Berry claimed at the trial that he thought she was twenty-four. He didn’t explain why he had asked her twice.

Berry asked if Escalanti had a job. “Sort of,” she said. He asked what she did. She told him she was a waitress. He asked what other work she did, she remembered, asking “if I had ever done any prostituting before.” She told him that she had.

Berry asked her if she would like to “reform.”

“Yes,” she said.

This was the moment that Berry chose to ask Escalanti about coming to St Louis to work for him. She was drunk, having been released from prison earlier in the day. She was alone, away from the band or the friends she was with earlier or those she would be with later. She clearly had no settled home. Even in Berry’s own explanation, it was their conversation about prostitution that prompted him to ask her to come with him to St Louis.

“I could see Janice in Indian attire in my imagination, and I thought she would be a drawing attraction as a hostess at Club Bandstand,” he wrote in his autobiography.

Escalanti said she had no money to get up north. Berry suggested she join him on the rest of his tour.

“I said okay but I would have to think about until after the dance.”

Eventually, Escalanti’s friend arrived and Berry drove to her house. Escalanti went inside to change. Berry became uneasy as he waited in the car. He asked a boy passing where “Heba” was. The boy said he didn’t know anyone of that name. Escalanti came out after about fifteen minutes. The dress she came down in wasn’t clean, Berry thought.

They drove back to the Coliseum. Berry handed her a pile of pictures, to sell to fans at the show. He didn’t mention paying her. There was one picture, Escalanti remembered, “where he was sitting, kneeling there with his guitar, and another one with just his face.” She had a little table, in the front entrance. Only a few people bought the pictures, twenty-five cents each, so she spent most of the time listening.

Berry played his set, his timeless songs of rock ‘n’ roll and teenage love and cars and high school. “Sweet Little Sixteen, she’s just got to have about half a million framed autographs,” Berry sang. “Sweet Little Sixteen, she’s got the grown-up blues.”

“Before half the dance was over,” Escalanti said, she told Berry she would go to St Louis. “He just said okay. He asked me, are you sure this is what you want to do. I said yes, that is what I want to do.”

It was about one thirty or two when they loaded the instruments into the Cadillac and left the Coliseum. Escalanti gave Berry the money she had made selling the photographs, wrapped in cellophane.

They drove back into Juarez and dropped the band off somewhere to eat. Berry and Escalanti drove back to the friend’s house, where Escalanti got some more clothes. She came down with “three dresses, a pair of shoes and a handful of incidental things,” Berry said. They didn’t seem to fit her, he thought, as if they belonged to someone else.

They collected the band and drove back into El Paso and then on towards Tucson, Arizona, through the night. Johnson drove, then Berry. The band kept their instruments in the trunk. Berry’s guitar was propped up tall on the back seat.

It was quiet. They rarely had the radio on and stopped only occasionally for food or gas. One of the car’s turning signals broke, but they carried on. The sun rose, casting shadows across the five passengers and Berry’s guitar, sat up like a person. When Johnson drove, Berry sat in the back, with his arm across Escalanti’s stomach, she said. They had coats over them.

Berry loved these journeys between gigs. Other musicians took tour buses but he liked to drive himself, or to sit in the back of his own car. He sang about it, on record and at gigs with Escalanti listening: in ‘Maybellene,’ he had “a Cadillac a-rollin’ on the open road;” in ‘No Money Down’ he sang about wanting a Cadillac with “a full Murphy bed in my back seat.”

A red Cadillac Eldorado, model year 1973, owned and driven by Chuck Berry.

Berry collected Cadillacs, kept them in storage, wrapped in plastic. In old age, he donated one to the Smithsonian.

“Essentially,” one of the museum’s curators said, “the Cadillac has come to symbolise Chuck Berry’s ability to commandeer his career.” In his songs, the curator said, the Cadillac meant “personal freedom, movement, and the general aspirations of America’s youth culture during the post-war era.” In the back of his cars, Berry said, “I can hide any time I want to hide, you know, when it’s time to hide.”

At around half nine in the morning, the Cadillac arrived at The Sands Motor Hotel, on the edge of Tucson. It was a roadside place, with a swimming pool enclosed on each side by two-storeys of rooms. It was colourful, with turquoise doors and dusky orange panelling. It still stands on the freeway, renamed, repainted a prison grey.

The Sands Hotel, Tucson (Source- William Bird, Flickr)

Berry checked in, signing his name in the registration card with a florid autograph. He listed Club Bandstand in St Louis as his home address. He and Escalanti got one room, Room 257. There were two beds in the room, and one bathroom. Berry’s three musicians shared another, with a connecting door through to Room 257. These were the last two rooms available, Berry said, saying he had no choice but to share a room with Escalanti. “I could not let her stay in the car,” he testified.

Escalanti told the court that she and Berry removed their clothes and had a shower together. Escalanti finished and got into bed, she said, the one closest to the bathroom. Berry finished and got in with her.

“When I speak of sexual intercourse, do you understand what I mean?” the attorney asked Escalanti.

“Yes.”

“Did he have an act of sexual intercourse with you?”

“Yes sir, he did.”

They fell asleep afterwards, she said, “slept most of the day.” When she woke up, Berry was still asleep. She lay there watching television for a while, until she got tired of it. She turned on the radio.

Berry woke. Escalanti, still naked, watched him dress. She got out of bed and put on a slip and bra. He rang down for some pork chops, strawberry shortcake, and coffee.

The bellhop brought it to the door. Berry answered, bare from the waist up. Escalanti was laid in the bed, pulling the covers up to her neck, “halfway dressed,” she said. Berry gave the bellhop an eighty cents tip. He and Escalanti ate. He then took pictures of her, she said, there in the bedroom. Berry admitted the pictures, and that he was half-dressed when the bellhop came, but denied everything else, the “sexual intercourse,” the shower, sharing a bed.

That evening, Berry called Janice Gillium, his secretary back in St Louis, the founder and national president of his fan club.

Berry told her he had “met an Indian girl.”

“What kind of an Indian?” Gillium asked

“Apache,” Berry said.

“I explained to her,” he testified, “told her I had an Apache Indian girl, that was going to work as the hat check girl, and what did she think about it, probably dress her in costume or something, and make a novelty of it.” He had a record then, ‘Broken Arrow,’ with lyrics about Cochise and Geronimo. He “figured we could use her on stage,” he said, “to push the song.”

Berry’s check in card for The Sands Hotel (Source: US National Archives)

Berry, Escalanti and the band then went to The Casino Bar, where Berry was due to play. It was much like El Paso. Escalanti sold pictures of Berry again and handed what money she had made to him at the end of the night. Again, he didn’t talk about paying her. After the show, Berry and the band went to a restaurant at Tucson bus station. You could get a bus anywhere from here, back to New Mexico, or Texas, a few hours down the freeway to Yuma, anywhere.

The attorney asked Escalanti what happened next.

“Well, then Chuck had taken two girls over to the hotel, with us, and Chuck went in the other room with…”

“He had what?” the judge asked.

“He had taken two extra girls over there to the motel,” she said. “He picked up two other girls.”

Berry had met the girls at the show that night. They were fans. Berry, the band, Escalanti and the two girls went into the band’s room, with the door through to Berry and Escalanti’s room.

Escalanti went through, next door to Room 257, leaving the others behind. She paced up and down. Davis came in and talked to her for a while, about the dance and the pictures she sold. He sat on the edge of the bed.

When Davis left, Escalanti got into bed herself. It was the early hours of the morning. Berry came in, just as she was about to fall asleep. He took off his clothes, she said, and got into her bed. They “had another sexual intercourse,” she said. When Escalanti woke up the next morning, she saw that Davis had come in, lying in the other bed in the room.

They left the hotel later that morning, and drove around Tucson, seeing the sights from the Cadillac. They stopped at a one-hour cleaners where they left some of Berry and Escalanti’s clothes, then to a filling station, where Berry had the car washed. He had the turning signal fixed. While they waited, they went to a department store and bought some clothes, “some skirts and sweaters and some shoes,” Escalanti said, which Berry paid for.

After they collected the car, they drove to a barber shop. Berry had a haircut. When he finished, he went to the beauty shop next door. “I had my hair pressed and curled,” Berry said, “as I wear it to present myself before audiences.” Escalanti waited for about an hour in the freshly cleaned car, parked outside, watching him through the shop window, pampered and refined.

They left Tucson around four or five o’clock, and drove to Phoenix. Escalanti lost track of time. It was a long drive, she said, “very long.” They pulled up outside the Mirador Ballroom, the venue for the night’s gig. “We went right in,” Escalanti said. She sold photographs again. “He played and we left.”

They drove on through the night towards Santa Fe, New Mexico. “A few minutes out, a few miles out,” Davis remembered, Berry “stated that his legs were tired, you know, and he was tired from the job, and he went to the back seat where he could stretch out more, so he asked Jasper and myself to move up to the front, and he and Janice moved to the back.”

They drove through national forests, and reservations. Sometimes they stopped. Occasionally, the men got out of the car, Escalanti remembered, and she stayed in it. From time to time, Davis asked her about “the different historical points up and down the highways.” She talked about the “olden days,” he said, and “described the Apache territory.” Eventually, Davis and Thomas fell asleep, in the front.

“You say it was on this trip that Mr Berry had relations with you in the back seat?” the attorney asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“While the car was driving on the highway?”

“Yes, sir.”

Escalanti was sat behind the driver, she told the court. Berry was between her and the guitar. She didn’t remove her clothing, she said, “not all of it.” Berry didn’t remove any clothing, she said. The poster was in the window above them.

During his own testimony, Berry suggested that the guitar, propped up, as big as a person, took up too much space to make sex on the back seat possible. Johnson, who was driving, told the court he didn’t see or hear anything, “nothing, not a thing. I never observed anything.”

They arrived in Santa Fe “in the afternoon, late in the afternoon,” Escalanti said. “When we stopped at the place where he was going to play, it was not time for him to play.”

The five of them went to a movie, to kill time. The gig was at Seth Hall, an adobe building next to a high school. Escalanti only sold four pictures that night. She didn’t get paid.

After the gig, they drove to Denver, through the night. It was about four in the morning when they left. Johnson drove first. Berry and Escalanti were on the back seat again, with the musicians in the front. Davis and Thomas fell asleep. Berry and Escalanti had “another sexual relationship” in the back of the Cadillac, she said.

“He asked me to make love to him, which I did not,” she said.

“What did he mean, Janice?” the attorney asked.

“He meant for me to go down on him.”

It was late afternoon by the time they arrived in Denver. They checked in at the Drexel hotel. Berry gave their name as “Mr and Mrs Janet Johnson” and didn’t enter an address, apart from “St Louis.” “I used her first name and Johnnie’s last name,” Berry said, “what I thought was her first name.”

“I never knew her last name until this case came up,” he testified, “but the first part of her name I thought was Janet, that is why I put Janet Johnson.”

Berry claimed he needed to use a pseudonym as fans would find out where he was staying and would call the hotel, asking for him. That had happened at the Drexel the last time he stayed there, just weeks before, he said. but he didn’t need to do it at other hotels.

Berry’s check in card for The Sands Hotel (Source: US National Archives)

He and Escalanti took Room 334. Davis and Thomas took another room, Johnson a third. Johnson had a woman with him too, listing their names on the check in card as “Johnnie Johnson & Mrs.”

Room 334 had one double bed. Berry hadn’t asked for a separate room for Escalanti. When he saw the double bed, he didn’t ask to be changed to a twin room.

Berry told Escalanti that she didn’t have to go to the gig that night. It was “sort of an exclusive date,” he said, at the Rainbow Club, “sort of plush-like.” He felt that Escalanti’s appearance wouldn’t fit in. “Some sort of sorority was connected with this dance,” he said, “and everybody would be in formals and what have you.”

Instead, Escalanti said, “I went out and ate and walked around a while.” She went back to the room, and slept.

After the gig, Berry called Gillium again, asking her if Escalanti could stay with her when they arrived in St Louis, in the house she lived in, which Berry owned. At about four in the morning, he went back to the hotel. According to the testimony of the night clerk, Berry went to the desk “and he asked me if his wife was in.” He wore a dark topcoat and hat, “like I have always seen him, when he comes in.” The clerk said he had seen Berry at the hotel the last time he was there, with another woman.

Escalanti woke to a knock at the door, she said. She got out of bed, opened it. It was Berry. She let him in. He got into the bed, the one bed in the room. “We had another sexual relationship”, she said. At the trial, Berry denied it, saying he had laid on the bed in his clothes for ten minutes, before falling asleep on the floor. He claimed he had never even wanted to have sex with Escalanti. However, in his autobiography, he suggested that Janice had “proceeded to undress right before me and climb into my bed,” while in Denver. “Without the challenge that usually confronts a guy,” he wrote, “I managed to postpone the joys, thinking we’d have a chance on the road later.”

The next day, he wrote, “when I awakened her, she boldly paraded into the bathroom in the buff and stayed twenty minutes, reappearing dressed and looking sad and unwanted as a homeless brown-eyed poodle. The day and evening passed slowly, and the courage I depended on was fast growing weaker, for I have always been subject to the sight of the female anatomy reaching my retina and taxing my tolerance.”

In the autobiography, he then included a poem that he wrote, seemingly dedicated to Escalanti:

“Maybe I should have let her go, but at the time I wanted to know/just what illusions she would fulfil, in following me of her own free will./I do not deny that it made me sad, knowingly missing what I could have had./Her love, whose origin, within her heart, was too immature to fail to depart.”

They next drove to Pueblo, Colorado. The days were merging into one. It was the weekend now, but Janice couldn’t remember if it was Saturday or Sunday. Janice didn’t sell pictures that night, though she went to the show. She “just sat there,” she said, “and danced.” It was Berry’s last tour show of the nineteen fifties.

After the gig, they drove across Kansas and over the border into Missouri. Berry drove all the way. He was tiring. He stopped the car in Kansas City, at the offices of Trans-World Airlines. He didn’t tell Escalanti that he was going to fly the rest of the way to St Louis until “just before he was leaving,” she said. “He told me that Johnnie was supposed to bring me into St Louis here.” She gave Berry the remaining money she had from the sales of the photographs, a small collection of coins wrapped in cellophane.

It was a week of travelling in total, two and a half thousand miles or so: from Mexico into the United States, out of Texas, through New Mexico, into and out of Arizona, back through New Mexico, up through Colorado, all the way across Kansas, all the way across Missouri. Five of them in the Cadillac, then four, through the nights and early mornings. Escalanti told the band that she was excited to see St Louis, that she had never been before, that she was looking forward to the job.

It was dark when they arrived in the city, about eleven o’clock. It was cold. She didn’t have a coat. Berry, she remembered, had to buy her one later that week. They dropped off Thomas, then Davis. Escalanti and Johnson went “right to Chuck Berry’s place,” she said.

Johnson got out of the car and unloaded his stuff. He was living there, in the back of Berry’s house. Escalanti followed him in. She didn’t see Themetta, Berry’s wife, or his children. Johnson told her that Berry wanted her outside. He was next to his car again.

Berry drove Escalanti to his office on Easton Avenue, she said. This was the fan club address, listed on the fan club membership card. Fans would sometimes wait outside, hoping to glimpse Berry, admiring his smile when he passed. Occasionally, Berry would greet the fans, tugging at the braids of young girls.

Escalanti said she slept there that first night in St Louis, in a room at the back, fixed up like a bedroom. The attorney suggested she and Berry had sex there but Escalanti denied it. She saw Berry, she said, but they didn’t have sex, not then. She was there “a night and a half a day,” she said. Berry rejected the idea she had ever stayed at the fan club address. He seemed to think it was important to emphasise that.

The next day, Escalanti moved again. Berry took her to 3137 Whittier Street. He had lived there with Themetta for a while, when they were first married, but he let Francine Gillium, his secretary, live there now. It wasn’t a big place. Berry carried Escalanti’s few things inside. Gillium greeted Escalanti. Escalanti introduced herself as “Heba Norine,” her “Indian name.”

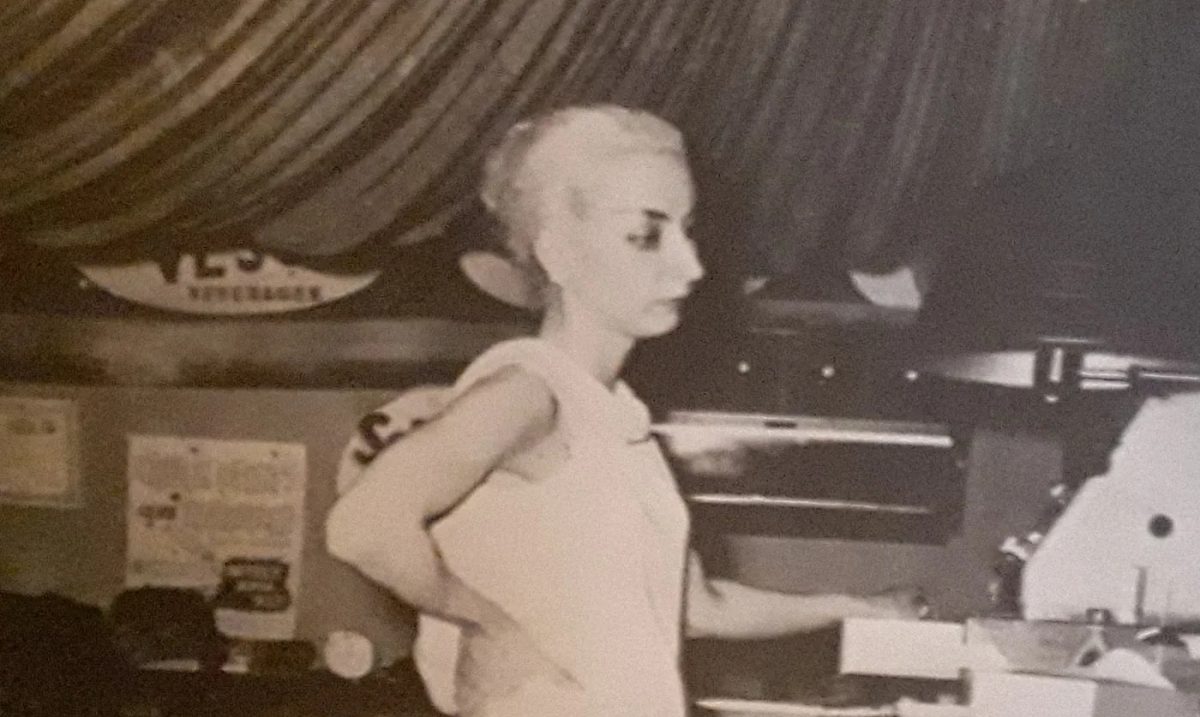

Francine Gillium behind the bar at Club Bandstand (Source- Chuck Berry, The Autobiography)

Gillium had been a fan once. She was twenty three now and had worked for Berry for two years. They met in Chess Studios in Chicago, when she was visiting. She was a strong advocate for Berry and his music: “rock and roll is a healthy, normal part of a teenager that should be encouraged in our attempt to create mature adults,” she had written earlier in 1959. From time to time, she accompanied Berry on tour. She had been with him in tour in October 1959, in Denver. The clerk at the Drexel Hotel remembered Berry referring to Gillium as his wife.

Soon, Gillium took Escalanti to Club Bandstand, Berry’s nightclub that she managed. It was down a flight of stairs from the street, a basement, beneath a cleaners and a restaurant. Anyone with a fan club card got in free.

“The whole club was dimly lit,” Berry told the court. The hat check room, where Escalanti was due to work, was especially gloomy. “We had a seven-watt bulb in there because the walls weren’t too good,” he said, “the walls weren’t finished.” The ceilings were low.

Berry felt that Escalanti gave the booth the appearance that he wanted. “The best appearance even under dim light would have been requested,” he said. Gillium dressed Escalanti “in a brilliant native costume with feathers,” he said, as he had planned. “My curiosity became a successful reality,” he wrote in his autobiography. He remembered being “proud of my idea and Janice in her costume.”

Berry often had a problem with keeping staff. The previous hat check girl had quit. “The girls would come and go at the club,” Berry said. He hoped for something different with Escalanti. “I was probably the only contact she had there for work and so forth, and by being in a strange place she might try hard.” At the club, he wrote, “she would break a slight smile only at those she knew very well. I took a liking to her beyond that of an employer.”

On her first night, Gillium asked Escalanti how old she was. Escalanti said she was twenty one. You had to be twenty-one to work in a nightclub, around liquor. Gillium asked for her birth certificate and her social security card. Gillium needed proof, she said, “because I didn’t know her.” Escalanti said she didn’t have it, it was at home. Gillium gave her a pencil, paper, an envelope and a stamp, and asked her to write home for it. She never asked again. Gillium said Escalanti would earn $5 per day, plus half of whatever she made in the hat check room but, without the social security number, she never paid her.

Gillium behind the bar at Club Bandstand, with Berry far right (Source: Chuck Berry, The Autobiography)

During the ten days Escalanri worked at the club, the routine was this: Escalanti and Gillium would get up around nine or ten in the morning; they would leave the house and go to the club around midday, to get the plave ready; Gillium would show Escalanti how to wash glasses, how to check coats; when they were hungry, Gillium would call the Chuck Wagon, the restaurant upstairs, to send food, or sometimes they would go up there to eat; occasionally, Gillium would take Escalanti downtown, to show her around, if they had time. The club opened at six. Berry was normally there for the evening, even if he wasn’t performing.

On the first night, Escalanti worked as a waitress. The next night, she worked checking hats. She got distracted and Berry complained. “He just said I should stay back there, not be wandering all over the place and be watching the customers as they come in,” she said. She kept getting distracted, over the next few nights, speaking to customers or watching the show. Berry kept reprimanding her, which made her angry, feeling he was unfair on her. Once, he saw her standing out of her box, and he pointed at it, saying nothing. She went back in.

“He just kept complaining about my not obeying him, and that I should do as he tells me to do and stay in the hat check room and do what I was told to do.”

When the club closed, around one thirty, Escalanti and Gillium would go back to the house. Escalanti never got a key, so Gillium would let them in. Sometimes Berry came with them, sometimes separately. By the time they got back, it would be about two in the morning. Escalanti would go to her room and get in bed. In the bedroom, she said, “I had a TV and a radio combination, there was a double bed, there were two dressers. One was a vanity and one was a dresser, there was a cupboard and there was a lounge chair.” Berry would come in, she said, and stay “about an hour and a half, almost two hours.”

Berry’s lawyer pressed her on the details at the trial.

“You were at Miss Gillium’s house ten or eleven days, weren’t you?”

“Yes.”

“Would you say… is it your testimony that at least ten of those night Mr Berry came over there and had sexual intercourse with you?”

“About nine or ten, yes.”

“Nine or ten times, practically every night?”

“Yes.”

After three days in St Louis, Escalanti said, she had decided to leave. “I just didn’t feel right being there with him anymore,” she said. She wrote to a man she knew in New Orleans, asking him to send her a bus ticket and some money. He didn’t reply. She didn’t leave. “I just did not feel right there,” she said, so quietly the judge had to ask her to repeat herself.

On the Saturday night, it was particularly busy. Gillium told Esclanti that she had been especially bad, walking out of the hat check room to see the show.

The club was closed on Sunday. Escalanti stayed in the house, then went to a show, with Berry and Gillium. Afterwards, on the first free night from working at the club, she went on a date with somebody.

On the Monday, Gillium moved her from the hat check, to collect admissions. Berry complained again, when she left the money box on the table. Escalanti said she was “just walking up to the bar, getting a glass of orange juice.” She didn’t smile while collecting admissions, Berry said, and she had been sitting with a man at a table, talking. “She did not have at all an appearance to welcome people into the club,” he told the court.

As the week went on, things deteriorated further. On the Thursday morning, Berry came over to the house on Whittier. He told Escalanti that she was still “disobeying him,” she remembered, that she was not doing her job properly. “You are going to have to leave,” he said, “I am going to let you go back to El Paso.” He had promised her this, he told her, that if things didn’t work out he would send her home. “I wondered when you were going to get around to that,” she said.

Berry told Escalanti to get her things together. He asked Gillium to help her pack, as he sat and watched television.

“I said Heba, Janice, excuse me, I am supposed to help you,” Gillium testified. “She was taking her clothes out of her cupboard, she was gathering magazines and her shoes and personal belongings, and she was putting them in a bag on the floor.” Escalanti put her three dresses in the paper shopping bag she got them in.

Berry took Escalanti to the Greyhound Bus Station. It was a futuristic place, with a wide waiting area and plastic bucket seats. Berry bought her a bus ticket and gave her some money for food, wrapped in the pamphlet they had given him the ticket in. The bus ticket was for El Paso. Escalanti said she wanted to go to Yuma, where her father lived, a fresh start, not El Paso or Mescalero. Berry told her a ticket to Yuma would to be too expensive, she said. He left her there, “right after he bought the bus ticket.” The bus was due to leave in an hour or two, at three thirty or four. “It was a long time before the bus came,” she said.

Escalanti waited for about half an hour. A man saw her, “a white guy,” she said. “I was just sitting there and he was sitting across from me.” He asked her if she drank. She said she did. “He asked me if I would go drink something with him, so I did.”

Escalanti left her paper bag in a locker in the bus station. They went to a bar nearby. She didn’t want to return to El Paso, to her life before, the arrests for vagrancy, drunkenness, prostitution. “After we started drinking, I just didn’t want to go back,” she said. She told the man where she was from.

“Who brought you clear up here?”

“Chuck Berry.”

The man knew about Berry and his club.

“Would you like to go back there and buy some drinks from there?”

“I don’t care,” Escalanti said.

They drove back to Club Bandstand, “Chuck’s place,” as she called it. A thousand miles from home, Escalanti went to the place in the city that she knew best. Escalanti and the man walked to the door together. “We were both at the door,” she said, “as far as I can remember.” She went in, down the stairs that led from the sidewalk. “When I turned around again he wasn’t with me.” She was drunk, she told the court, quietly.

Gillium saw her and went to stop her. She could smell the drink. She told Escalanti to hold on to the bannister, to steady herself. She was falling, Gillium said. Gillium helped her up and straightened her clothes.

“What do you want, Heba?” Gillium asked.

“I want to see Chuck.”

“You will have to get sober before you can come in here and see him.”

Escalanti climbed back up the stairs, and left.

Advertisement for Club Bandstand (Source: St Louis Post-Dispatch, 12th March 1959)

The next night, she came back to the club. She got in and sat in a booth. Berry saw her. He came over and sat halfway in the seat. He asked where her purse was. He rifled through, took the bus ticket and the money and walked away. He didn’t say anything to her after that.

Escalanti sat around talking to “some of the guys that performed at his club,” she said, and with Davis and Thomas. Later, someone told her that Berry had kept the ticket, ready for her when she left. She never took it back. Berry gave it to Gillium. She left it in the club cash register for over a year.

Escalanti stayed in the club until closing time. She was angry, she said. She was weaving from side to side as she walked, Gillium remembered. When she left the club, Davis saw her, standing outside. She told him she was cold. She told him that she didn’t know where she should go. Davis and Thomas took her to a hotel, the De Luxe, the same name as the club she had worked at after she got out of prison in El Paso.

“Did you have any sexual acts of intercourse with her at all?” the attorney asked Davis, when his time came to testify.

“Yes, I did.”

“Where was that?”

“At the De Luxe Hotel.”

Berry’s lawyer asked Escalanti how she made money while she was at the De Luxe. “Through prostituting,” she said. This was how she would make enough to get home, she thought. “That’s when I figured that if I could go back to prostitution work again, probably get my money easier that way to get back to Yuma.”

Berry was unsympathetic. “I had nothing to do with corrupting her,” he wrote in his autobiography, “since she was just starting up again something she had already been doing.”

The next day, Escalanti rang the club. “She called all day,” Gillium said. Berry was always busy, Gillium said, either away from the club or in the recording studio in the back, and she couldn’t disturb him. It was “continuous,” Gillium said. Escalanti was desperate to get home.

Eventually, she got through to Berry, while he was recording in the studio. She had changed her mind, cooled off, she said. She wanted the bus ticket, wanted to go back to El Paso. “I was ready to leave,” she said. Berry told her that she couldn’t have the ticket as he had already turned it in. He said he would take her back to the bus station and “put you on the bus.”

Escalanti didn’t go back to Club Bandstand for another three days. It was dark when she got to there, after midnight. She got a taxi, from the De Luxe Hotel. She had been drinking. She had called the club a couple of times that day. Gillium remembered that she was angry on the phone, that she said Gillium would pay for it, for not getting Berry on the phone.

When Escalanti arrived, Gillium wouldn’t let her in. “It’s Chuck’s orders,” she said.

“I walked around the block and I made up my mind,” Escalanti told the court, “if he was going to act dirty I might as well act dirty, too.”

“What do you mean?” Berry’s lawyer asked.

“Well, if he is going to be stuck up and treat people mean I might as well be the same way he is.”

She went to the Chuck Wagon restaurant above the club. She thought about the conversation she had with Berry back in El Paso, about “reforming,” about how Berry hadn’t helped her. She had some coffee. She thought about her future, how she felt she would end up going back to prostitution.

She wrote a note, which was presented as evidence in court, as Defendant’s Exhibit A. “Dear Chuck,” she wrote, “like I said before, I love you.”

“I don’t know what my feelings were for him, but I’m pretty sure that it wasn’t love,” she testified.

She called the police in Yuma, Arizona. She didn’t want Berry arrested, she said. She asked them “what I should do to try to get back home again.”

“They told me just wait there,” she said, “and they would get in touch with the police here and they would send somebody after me.”

The St Louis police arrived at the Chuck Wagon. She was sitting in the phone booth when they arrived. She told them about Berry, what had happened. She told them she was fourteen. She told them she was angry with Berry for trying to send her to El Paso. They arrested her. They arrested Berry too.

The officers put Berry and Escalanti in the back of their car and drove them to the Ninth District station. It was a one storey Art Deco building, like a small movie theatre. It was late, the buff bricks dark.

The St Louis police notified the FBI, who questioned Escalanti. She told them about the trip from Juarez to St Louis. While she was locked up, she thought about the backseat of the Cadillac. She had left out those parts when she spoke to the police. She had left out the part about staying at the fan club office too.

Berry was charged with “transporting” Escalanti two days before Christmas 1959. Early in the new year, at the dawn of the nineteen sixties, he was charged with “transporting” Mathis Bates and with the firearms offence. He was granted bail, free to go about his business.

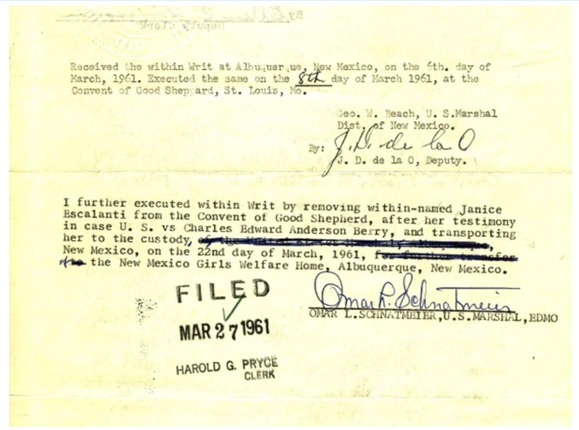

The US Attorney was concerned that Escalanti would leave St Louis before the trial. She was, he said, a “delinquent.” He sought a court order, directing her to pay a bond of $500 to ensure she would testify. She didn’t have $500, so she was detained at the House of Good Shepherd, a nineteenth century convent which served as a children’s home. There were iron bars on the windows and heavy iron gates. A high concrete wall surrounded the place. She stayed until the start of the trial, 29th February 1960, and then into March, as she told the lawyers and the judge and the jury her story.

The weather was terrible through the trial. It was cold. Ten inches of snow fell.

“Here is a famous performer, a TV and record idol,” the attorney said, summing up the case, “a rock and roll singer of national fame whose concerts and entertainment is pointed for one group of people, teenage children, and here he has a teen-age child, fourteen years old, although she comes from a horrible background she is still a young girl.”

Berry was found guilty. He began crying, bent double, as the judge delivered his sentence. “Don’t go through that maudlin exhibition in my presence, I am not impressed by it,” the judge said. “I have seen your kind before.”

“I would not turn that man loose to go out and pray on a lot of ignorant Indian girls and coloured girls, and white girls, if any. I would not have that on my soul.”

Berry was taken to St Louis jail by the same US Marshal who had taken Escalanti into custody. Berry appealed, and he was freed from prison. At appeal, though the judges found Escalanti believable, he was granted a retrial, due to the judge’s racist remarks. Berry was free, pending the retrial.

Escalanti was detained at the House of Good Shepherd until May 1960. From there, she was taken to the New Mexico Girls Welfare Home, Alburquerque, by the US Marshal, travelling for ten days by car across states.

While awaiting the retrial, Berry was found not guilty in the second “transportation” case. Although he admitted to having sex with Joan Mathis Bates, who was seventeen and therefore of the age of consent, both he and Mathis Bates told the court that they were in love, so the “transportation” was not “immoral.” At the end of the Mathis trial, Berry wrote, she rang him to wish him “good luck on the Apache trial.”

Berry was also acquitted in the firearms trial. The court held that the officer did not have the authority to search Berry’s Cadillac, so the loaded .25 caliber pistol he found was inadmissible as evidence. At his court date, two hundred fans waited for him, screaming, waiting to touch him, in his white suit with metallic silver threads, his dark glasses and black suede shoes.

In March 1961, the US marshal drove Escalanti back to St Louis from Alburquerque, for the retrial. She was detained in the House of the Good Shepherd again. “She wasn’t real happy about coming back,” the attorney remembered in Berry’s biography. “The Mother Superior called me, and said, ‘you better get this case over with in a hurry’ because she seemed to be driving them crazy over at the convent.”

At the retrial, Berry wrote, “the courtroom was jam-packed, as if I was indicted to strum out a string of rock ‘n’ roll hits.”

Escalanti spoke louder this time. She was fifteen now. The attorney stood further way from her, forcing her to project. She told her story again, the same story, though she couldn’t remember it quite as well. Berry’s lawyer told the jury that Escalanti was “dumb like a fox. Everything we have heard about Indians being cunning is true.” Nevertheless, Berry was found guilty. Escalanti’s testimony “was harmful in that it generated much pity in her favour,” Berry wrote.

Before sentencing, the judge called the lawyers into his chambers, as recounted in Berry’s biography. “I learned an old rule when I was young,” the judge said, “if you’re going to fuck a whore, you’ve got to pay ‘em.”

Berry was sentenced to three years in prison and a $5000 fine. He appealed again, though unsuccessfully this time. Again, the judges found Escalanti credible. Berry was eventually taken to prison in February 1962.

The marshal drove Escalanti back to Alburquerque again, back to the custody of Girls Welfare Home. This was not just a children’s home. Girls served sentences there too. There was a psychologist and enforced activities. Girls often tried to escape. It was often violent. Girls at the Welfare Home were usually detained until they were eighteen: including her time at the House of the Good Shepherd in St Louis, Escalanti was likely in custody for four years.

Chuck Berry in the 1930s

In prison, Berry wrote poetry: “I, among these men in grief, must be firm in my belief, that this shall not be the end, but my chance to rise again… back to freedom, maybe fame.”

His fame didn’t just survive the conviction, it embraced it. Even Berry acknowledged the link between his songs and Escalanti. When the story of the trial hit the newspapers, Berry wrote, “some of my hundred or more songs did fit part of their clippings, but I never saw in any where I would have gotten credit for predicting the event.”

Whereas those earlier songs could be passed off as fiction, the songs he wrote in prison undeniably reflected the reality of his recent trials. Just as touring and his club couldn’t be separated from his conviction, neither could what he sang about. Some of his prison songs became hits, unavoidable classics, quintessential rock ’n’ roll.

In ‘No Particular Place To Go’, he wrote that “riding along in my automobile, my baby beside me at the wheel, I stole a kiss at the turn of a mile, my curiosity running wild.” In ‘You Never Can Tell’, “the French trial” not long behind him, he wrote about a “teenage wedding” of a girl he calls “Mademoiselle.” The song turns on the premise of the surprising maturity of the teen lovers. “The old folks,” of course, underestimate them, with their “little records all rock, rhythm and jazz” and a “souped-up” red car which they drive cross country. There was a strange, “coffee-coloured Cadillac” in ‘Nadine,’ and a “rotten, funky jail” in ‘Tulane.” In ‘Promised Land’, Berry again wrote about travelling across country, complete with references to Greyhound buses, and a fantasy that “I woke up high over Alburquerque on a jet to the promised land.”

While Berry was in prison, white teenagers who played his music began attracting attention. The Rolling Stones released ‘Come On’, their first single, a cover of a song Berry had recorded while waiting for the retrial, the last single he released before going to prison. The Beach Boys based ‘Surfin’ USA’ on ‘Sweet Little Sixteen.’ The Beatles covered more of Berry’s songs than of any other artist. “If you tried to give rock ‘n’ roll another name,” John Lennon said, “you might call it ‘Chuck Berry.’”

Berry was released at the end of 1963, after twenty months in prison. He began touring again and having hits. In the press, he denied he had ever been convicted.

Chuck Berry and his wife, Themetta, in 1948.

In 1979, he was convicted of tax evasion and served a further prison term, where he began writing his autobiography. He would write pages by hand, then send them to Gillium to type up.

The book attempted to reframe the Escalanti trial, to excuse it. Despite the trial focusing on whether the transportation was for the “purposes of immoral practices” rather than the fact of any abuse, he now admitted that he had wanted to have sex with Escalanti, though he still denied they ever had and denied knowing her real age.

The autobiography’s cover featured a pose similar to the fan club picture he had given to Escalanti, with Berry kneeling, topless, holding his guitar. This time, he looked straight at he camera, half smiling, the neck of the guitar pointing down between his legs.

He seemed deliberately provocative: “my autobiography would have been much more complex had the time and attitude of the public been right for the exposure of truly explicit information about my personal adventures,” he wrote. He intended to write another book, he said, “one that I will enjoy, the true story of my sex life.” That book, he wrote, would detail “my excessive desire to continue melting the ice of American hypocrisy regarding behaviour and beliefs that are now ‘in the closet’ and only surface in court, crime, or comical conversation.”

In 1990, a class action suit was brought against Berry for making secret video recordings of women in the bathroom of a restaurant he owned. He settled out of court. Criminal charges were also brought, as some of the video recordings were of minors. The criminal charges were dropped as part of a plea bargain relating to charges of possession of marijuana, for which he served two years unsupervised probation.

Berry died in 2017, to much fanfare and some controversy. He perfected rock ‘n’ roll, people said, he was a great, they said, a lyrical genius. He mythologised teenagers, they said, even invented the very idea of them. Escalanti was sometimes mentioned.

What Escalanti did after the retrial is harder to establish in any detail: marriage and death records, occasional notices in the local press and family gravestones give little more than an outline of her life. Compared to Berry, the lack of information makes it appear quiet.

After she was released from the Girls Welfare Home, it seems she finally went to Yuma, where she met her first husband. They married in 1966, when she was twenty. By the time she was twenty four, she was back in Mescalero, using her maiden name. She had been hit by a car, hospitalised. After Berry published his autobiography in the eighties, her name was used more often in the press. Before then she was usually just “an Apache girl” or “a fourteen year old,” if she was mentioned at all. Now she had a name. Often it was written as “Escalante,” the misspelling Berry used in his autobiography.

In the nineties, Escalanti married again. Her husband died in 1999. She fell in love with another man, though they never married. He died in 2018. It seems they had lived together, on a dead end road overlooking the interstate.

Charles Edward Anderson Berry (October 18, 1926 – March 18, 2017) was an American singer, guitarist and songwriter who pioneered rock ‘n’ roll.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.