On Monday, 5th November 1956 just four hours before the curtain rose, and to the shock of the still-rehearsing all-star cast which included Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh, but also Sabrina backed by the Nitwits, the Royal Variety Performance was suddenly cancelled. Perhaps Olivier who had recently been speaking Terence Rattigan’s lines for the Regent in the play The Sleeping Prince night after night, ‘I will not have my country made the pawn of British imperialism and French greed’ understood the underlying reasons of the Suez Crisis.

The day before and not sitting on the fence, the Observer had written of the Suez Crisis, declaring that the action against Egypt had ‘endangered the American Alliance and Nato, split the Commonwealth, flouted the United Nations, shocked the overwhelming majority of world opinion and dishonoured the name of Britain’.

The protest about the Suez Crisis, Trafalgar Square, 4th November 1956

British Troops Leaving For The Suez

Egyptian prime minister Nasser announces that he as taken over the Suez Canal Company

Later that Sunday afternoon, demonstrating under the banner ‘Law not War’ 10,000 people gathered at a huge rally at Trafalgar where Aneurin Bevan told the crowd: ‘We are stronger than Egypt but there are other countries stronger than us. Are we prepared to accept for ourselves the logic we are applying to Egypt?’ To the crowd who were now loudly applauding he continued: ‘If Sir Antony is sincere in what he says – and he may be – then he is too stupid to be Prime Minister.’ Twenty years previously, as foreign secretary, it had been Anthony Eden who had helped negotiate an Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of Friendship and Alliance telling the House of Commons at the time: ‘Because of the Suez Canal the integrity of Egypt is a vital interest of the British Empire as well as of Egypt herself.’ His face had even appeared on an Egyptian postage stamp that year.

After Bevan’s speech many of the crowd started streaming down Whitehall towards the Prime Minister’s residence, all the while chanting: ‘Eden Must Go, Eden Must Go’. The crowd were met with a ring of police protecting Downing Street, and many demonstrators became bottled in and had nowhere to go. In the confusion, some mounted police charged down Whitehall and rode right into the demonstrators scattering them everywhere.

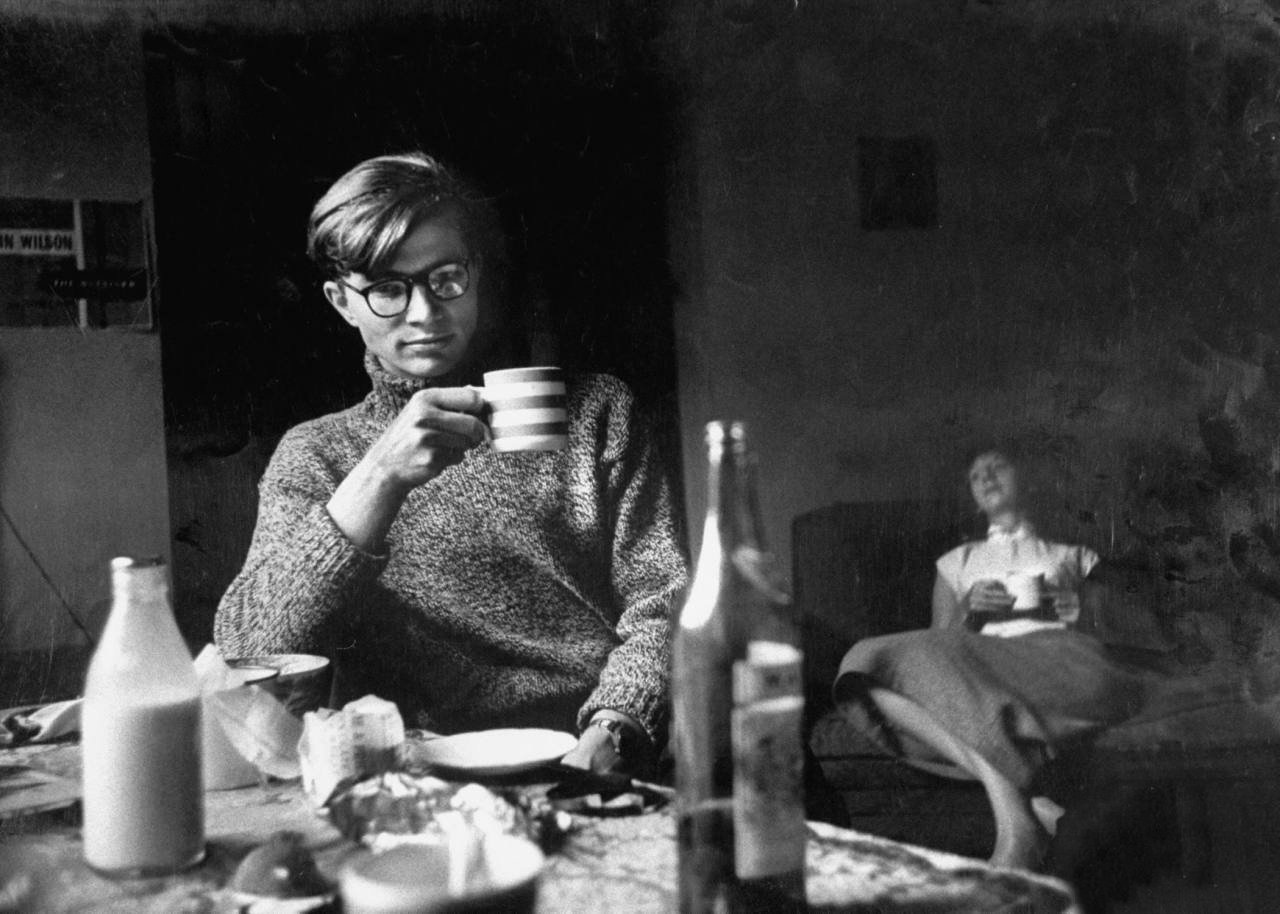

Colin Wilson drinking tea with his girlfriend Joy.

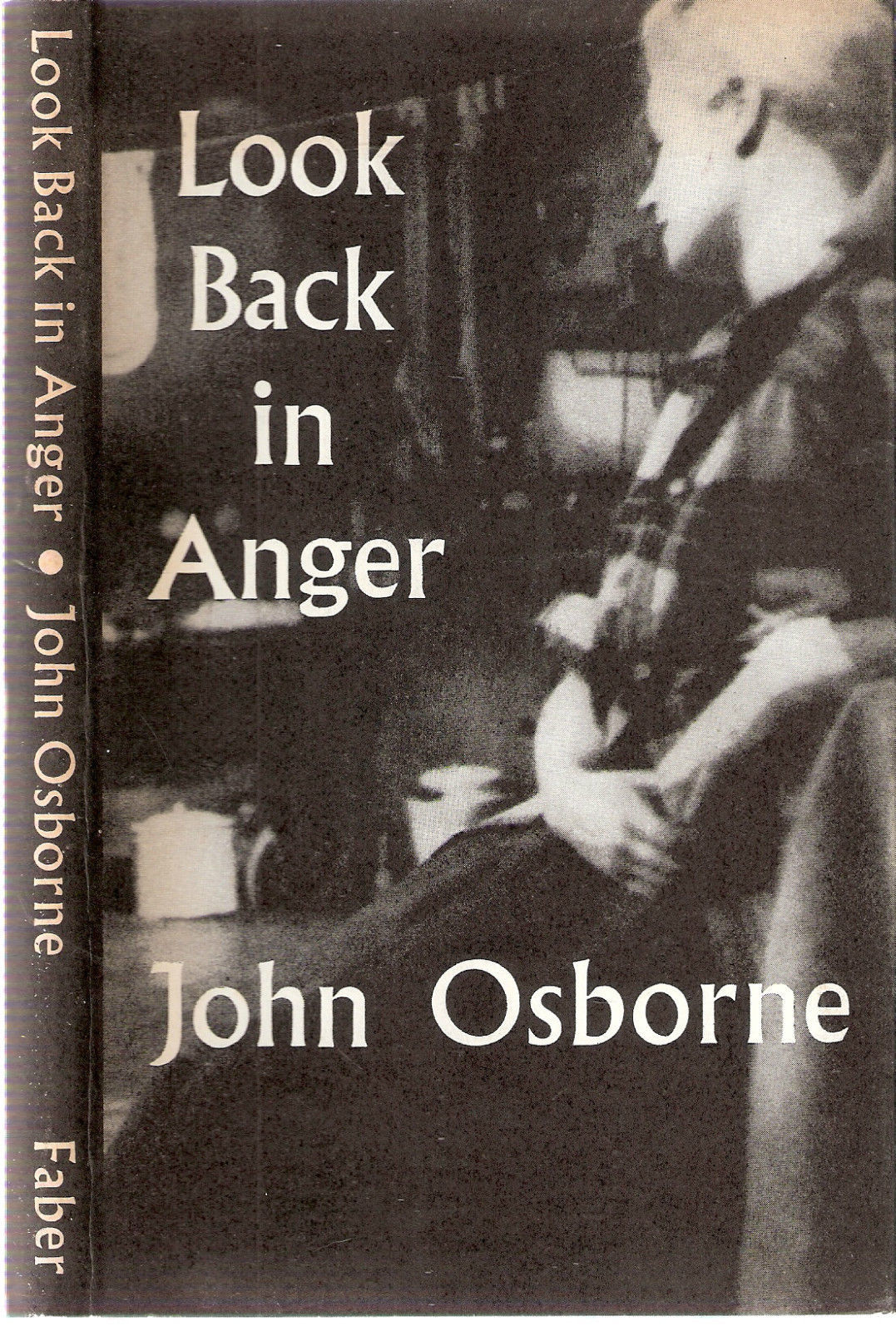

1956 was also the year of the so-called Angry Young Men. The first and most immediate examples that contributed to the Angry Young Man myth were Colin Wilson’s The Outsider and John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger both of which came to the public’s notice in May of that year. On the 8th, almost exactly a year after the jobbing actor Osborne had written in his pocket diary – “Began Look Back in Anger”, his infamous play opened at the Royal Court Theatre on Sloane Square. The actual term ‘Angry Young Man’ was coined by the Royal Court’s press officer George Fearon who thought he needed to give a boost to a play he initially considered almost impossible to promote.

Two weeks after the opening of Look Back in Anger,The Outsider was published. To, it has to be said, almost universal acclaim. Famous, almost literally overnight Colin Wilson was taken for lunch at the Athenaeum by Aldous Huxley. Wilson would later describe the meeting in his autobiography “He was very tall, almost blind, with a rather thin, slow voice. I remember saying to him, as we stood side by side at the urinal: ‘I never thought I’d be having a pee at the side of Aldous Huxley,’ Huxley replied: Yes, that’s what I thought when I was standing beside George V.” Huxley, who by then had been the author of coming onto fifty books let alone almost countless essays, had just published his tenth novel, “The Genius and the Goddess”. The ‘genius’ in Huxley’s novel was a Nobel-prize winning physicist but in 1956 it was also a word used to describe Colin Wilson – not unsparingly either that year – and he was just 24.

Daniel Farson, an early British television star as a reporter for Associated-Rediffusion, but in 1956 writing for the Daily Mail, wrote: ‘I have just met my first genius. His name is Colin Wilson.’ The object of his praise, not a man particularly known for his modesty, said that from the age of thirteen: “I had taken it for granted that I was a man of genius.”

For a few short months after the publication of The Outsider, it almost seemed the rest of the world thought so too. Wilson’s book was a collection of essays that explored the philosophical idea of ‘the outsider’ in literature, including that of Kafka, Camus, Hesse, Sartre and Nietzsche. It seems astonishing today that, within a few days of publication by Gollancz, in May 1956 the young author was rocketed into celebrity orbit for what was essentially a book of existential literary criticism. [Incidentally it was exactly a year later when anything beyond a metaphor was sent into orbit from Earth when the spherical Sputnik was launched by the Soviet Union – the satellite elliptically travelled around the earth for three weeks until its battery died and two months later it burnt up when it fell into the Earth’s atmosphere].

The Outsider was a good way, perhaps, for many of the tens of thousands who bought it, of making an acquaintance with intellectual foreign authors without the laborious obligation of actually having to read any of their books. Incredibly, Gollancz sold out their initial print run of 5,000 copies on the very first day of publication.

At this stage no one seemed to notice that Wilson was agreeing, far too readily than was healthy, with the ‘genius’ part of his description. In his journal Wilson wrote: ‘This book … should be the most important book of its generation.’

Unlike The Outsider, which was successful from the very first day of publication John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger, initially, was seen as almost a failure. Dimissed by most critics – for instance the Evening Standard described the play as having the stature of a self-pitying snivel.’ However Kenneth Tynan, almost on his own, liked what he saw, and wrote in the Observer although at the time to no real effect – “All the qualities are there, qualities one had despaired of ever seeing on the stage…I doubt if I could love anyone who did not wish to see Look Back in Anger.”

There was an audible gasp from the audience when an actual ironing board was seen on a London stage

Kenneth Haigh with Mary Ure in the 1956 Royal Court production of Look Back in Anger

Photographs of the original production of Look Back in Anger by John Osborne (Royal Court Theatre, 1956)

1956 ‘Look Back in Anger’ rehearsal Royal Court Theatre

1956 happened to be the first complete year of commercial television in the UK but it was the BBC which showed a 25 minute extract (basically a huge advert for the play) that suddenly Look Back in Anger took off.

The play was a reaction to the staid upper middle class dramas from the likes of Terence Rattigan, Noel Coward and J. B. Priestley – writers of the so-called “well made play” – derided as mere craftsmen not artists. To that taunt Priestley once said, “you wouldn’t mock a table for being well-made would you?” Priestley was actually name-checked in the play as someone, Jimmy Porter explains who’s “like Daddy-still casting well-fed glances back to the Edwardian twilight from his comfortable, disenfranchised wilderness…”

The Bradford-born writer didn’t take this particularly well. Apparently in the 1960s, a few years after co-founding the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmanent, Priestley – who, as a young man, had been buried alive and gassed during WW1 spoke to a gathering of the new Royal Court writers.“Angry! I’ll tell you about angry,” he told them, biting on his pipe. “I was angry before you buggers were born!”

Noel Coward wrote in his diary (february 1957) “I Wish I knew why the hero is so dreadfully cross and about what? …I expect my bewilderment is because I am very old indeed and cannot understand why the younger generation, instead of knocking at the door, should bash the fuck out of it.”

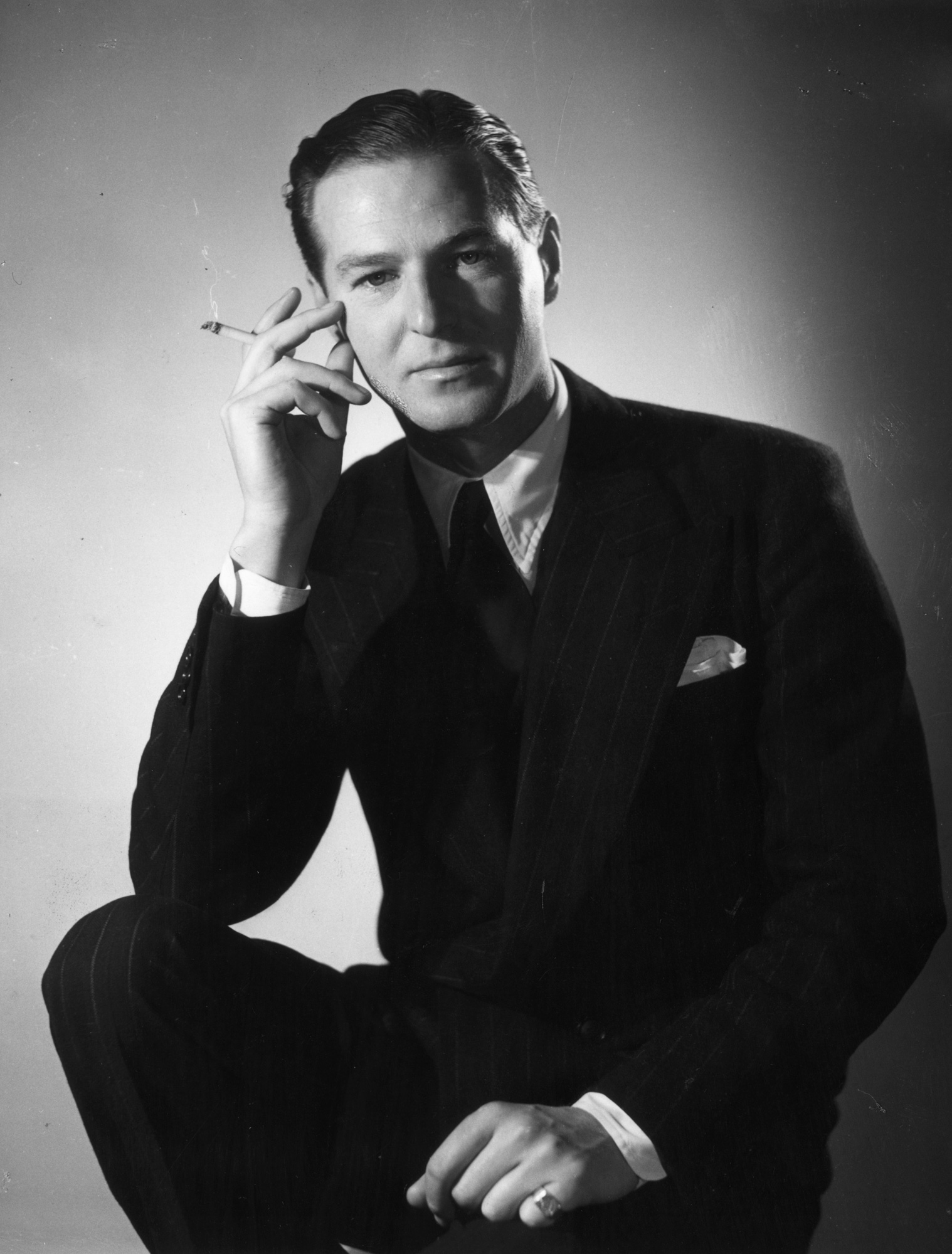

Terence Rattigan was actually at the first night of Look Back in Anger and witnessed the audible gasp when Alison Porter, played by Mary Ure, was seen at an actual ironing board. He didn’t enjoy what he saw and went to leave at the interval – although he was dissauded. When he eventually did exit the theatre he told reporters that the play should have been called ‘Look Ma, ‘I’m not Terence Rattigan’.

For the decade after WW2 Terence Rattigan, educated at Harrow and Trinity College, Oxford and now a Knight of the realm was, as his biographer put it ‘unquestionably the pre-eminent English dramatist’. That year, in 1956, his Separate Tables had run successfully in London and New York he was the writer of the plays and the subsequent film scripts of the Winslow Boy and the Browning Version not to mention the screenplays of The Way to the Stars and Brighton Rock. His play The Sleeping Prince was now to be made into a film with Marilyn Monroe.

Towards the end of 1955 Rattigan had arranged to meet Marilyn Monroe in a cocktail bar in Mahattan. An Italian journalist who had accompanied the playwright on the trip wrote of him: “the son of an ambassador and a handsome young man [with] the build of a grenadier, the body of an athlete, the head of Apollo and the manners of a diplomat…dressed with the greatest elegance with a gold cigarette holder by Faberge and a Maharahah’s Rolls Royce.”

Rattigan, of course, arrived on time and by the time Marilyn arrived an hour later he had consumed three martinis. She turned up wearing dark glasses and as he put it – “Greeted me with that deliciously shy self-confidence that had overwhelmed so many thousands of tough and potentially hostile press men’. Rattigan, apparently only understood about one word in three that she said and he was pretty sure ‘she didn’t understand a word I said’. Nevertheless she managed to convince him that she wanted to buy the rights to The Sleeping Prince. Then she shyly asked Rattigan whether ‘Sir Larry’ would do it with her. Geoffrey Wansell in his biography of Rattigan quotes the playwright:

“Gazing into those beautiful and childishly knowing eyes – she had removed her dark glasses – what could I reply but yes? I was sure ‘Sir Larry’ would leap at the chance, I said, and I would leave no stone unturned to see that he did.”

Terence Rattigan

Rattigan, Olivier, and Monroe

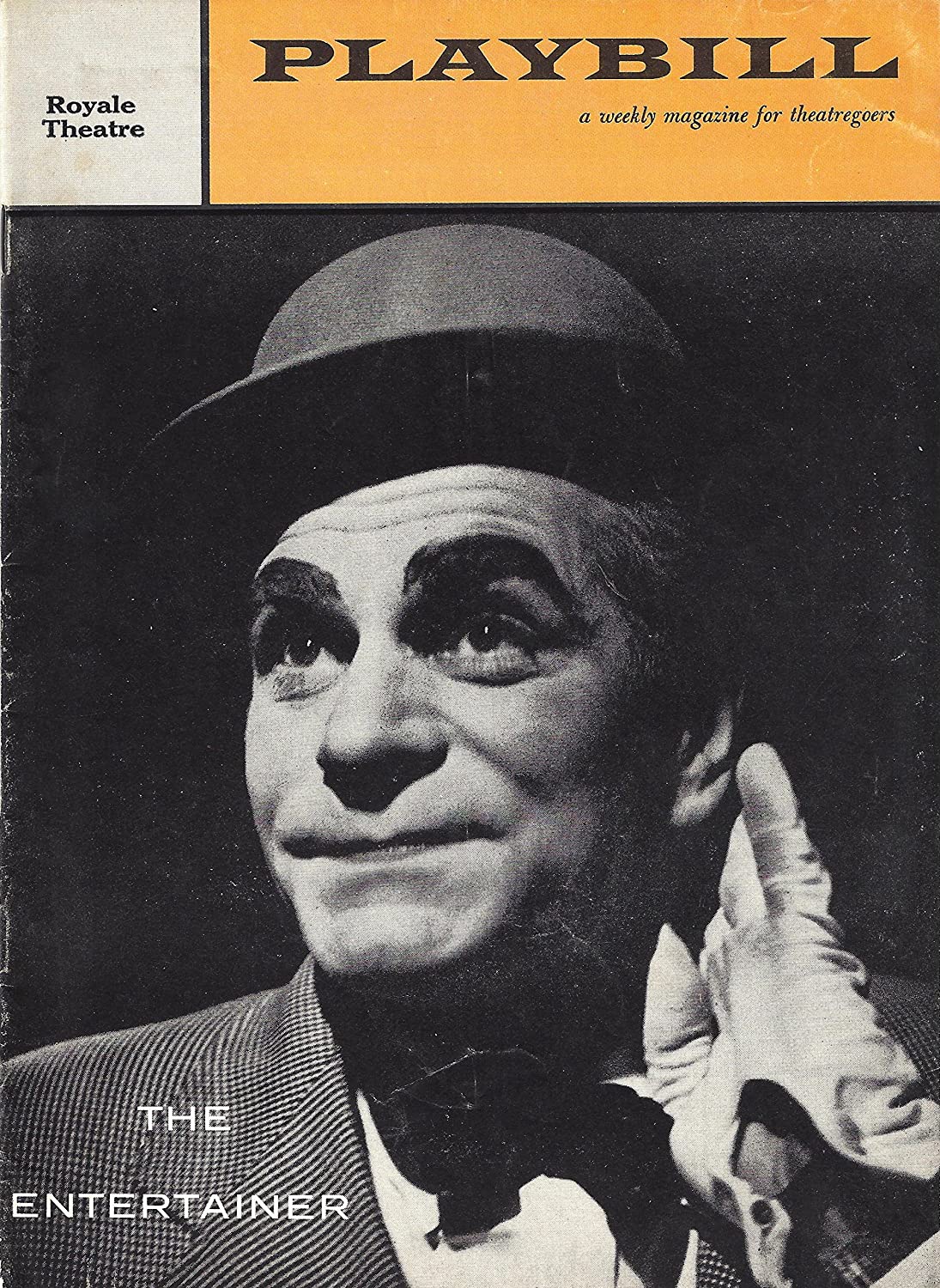

Laurence Olivier was initially unimpressed with Osborne’s Look Back in Anger but Arthur Miller (in the UK accompanying his wife Marilyn while they filmed what was to become The Prince and the Showgirl) wanted to see the play that John Lahr would later describe in the New York Times as having “wiped the smugness off the frivolous face of English theatre,”. This is great stuff’ Miller told Olivier at the Royal Court although the actor was still relatively unimpressed. Miller was therefore more than surprised when he heard Olivier, knowing full well he had found himself in a middle aged acting rut, asking Osborne if he had a little role for him in the future. When the first act of The Entertainer arrived, almost it seemed to Olivier with indecent haste, he agreed to play a career changing Archie Rice.

The week after Marilyn and Arthur left London after filming of the Prince and the Showgirl had completed, the Chelsea Palace of Varieties closed down as a theatre and music hall for good. It was where John Osborne had seen Max Wall perform a few months earlier that inspired The Entertainer. Less than six months later the play opened at the Royal Court with Olivier playing Archie Rice to great acclaim. Olivier was now appearing in a play which began in November 1956, when Archie’s 22-year-old daughter Jean visits her family at their digs in “a large coastal resort” just a few days after she has joined the Trafalgar Square peace rally that saw protesters denounce Eden’s aggression.

“At the beginning of 1957,” wrote Osborne in his autobiography, Almost a Gentleman, “the muddle of feeling about Suez … was so overheated that the involvement of Olivier in the play seemed as dangerous as exposing the royal family to politics”. Olivier had written to Osborne thanking him for the extraordinary part and that he hoped he wouldn’t “fuck it up for him”. The opposite happened and as Simon Callow once wrote: “It is not given to many actors to embody the zeitgeist: Olivier’s Archie presented post-Suez, mid-century Britain to itself in all its tarnished, seedy, impotent dishonesty, surgically exposing all the pain that lay behind it.”

Laurence Olivier in the 1957 stage version of The Entertainer.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.