When Robert Lenkiewicz (1941–2002) died from a heart attack at his Plymouth, Devon, art studio, he was not alone. The embalmed body of a man known as Diogenes was in a concealed drawer in the painter’s library.

Diogenes had spent most of his life as Edwin McKenzie (1912-1984). Things changed when in the late 1960s, Lenkiewicz found him living inside a concrete barrel at a rubbish tip on the outskirts of the city. The artist had an interest in vagrants and people on the edge of society. During the 1960s, he completed a “Vagrancy” study of the lives of tramps in London and Plymouth.

From the Robert Lenkiewicz Foundation’s website.

Living cheek by jowl with the vagrants who had begun to doss down in Lenkiewicz’s home put enormous strains on the artist’s families, but the Lenkiewicz’s Schweitzerian experiment was only just beginning. ‘The Cowboys’ Holiday Inns’ (an ironic reference to the popular hotel chain) was the name given to the derelict warehouses in Plymouth commandeered by Robert Lenkiewicz to house the growing numbers of vagrants attracted by his charity. At any given time, there might be up to ninety vagrants bedding down in about nine different properties.

It was to one of these ‘dosses’ – called ‘Jacob’s Ladder’ because entry could only be gained via a short ladder – that the great and the good of the Plymouth establishment were invited in March 1973 to view a large exhibition on the theme of Vagrancy. Three vast paintings dominated the space, including The Burial of John Kynance, homage to Courbet’s painting A Burial at Ornans (1849-50). In Lenkiewicz’s treatment the mourners Doc, Blue, Harmonica, Barney, Cockney Jim, Taff, Wee John, Diogenes and Cyril, are seen from the point of view of the corpse in his coffin whilst the skeletal personification of Death dances amongst them (sadly, this painting and many others were destroyed in a suspected arson attack in 2012). A new palette of close-toned colours – greys, greens and earthy browns – gave these paintings a reflective, elegiac quality. One of the tramps, Black Sam, remarked: “Fine stuff, fine stuff! But when I looks at the pictures o’ the lads, I feels like I’m in a mortuary.”

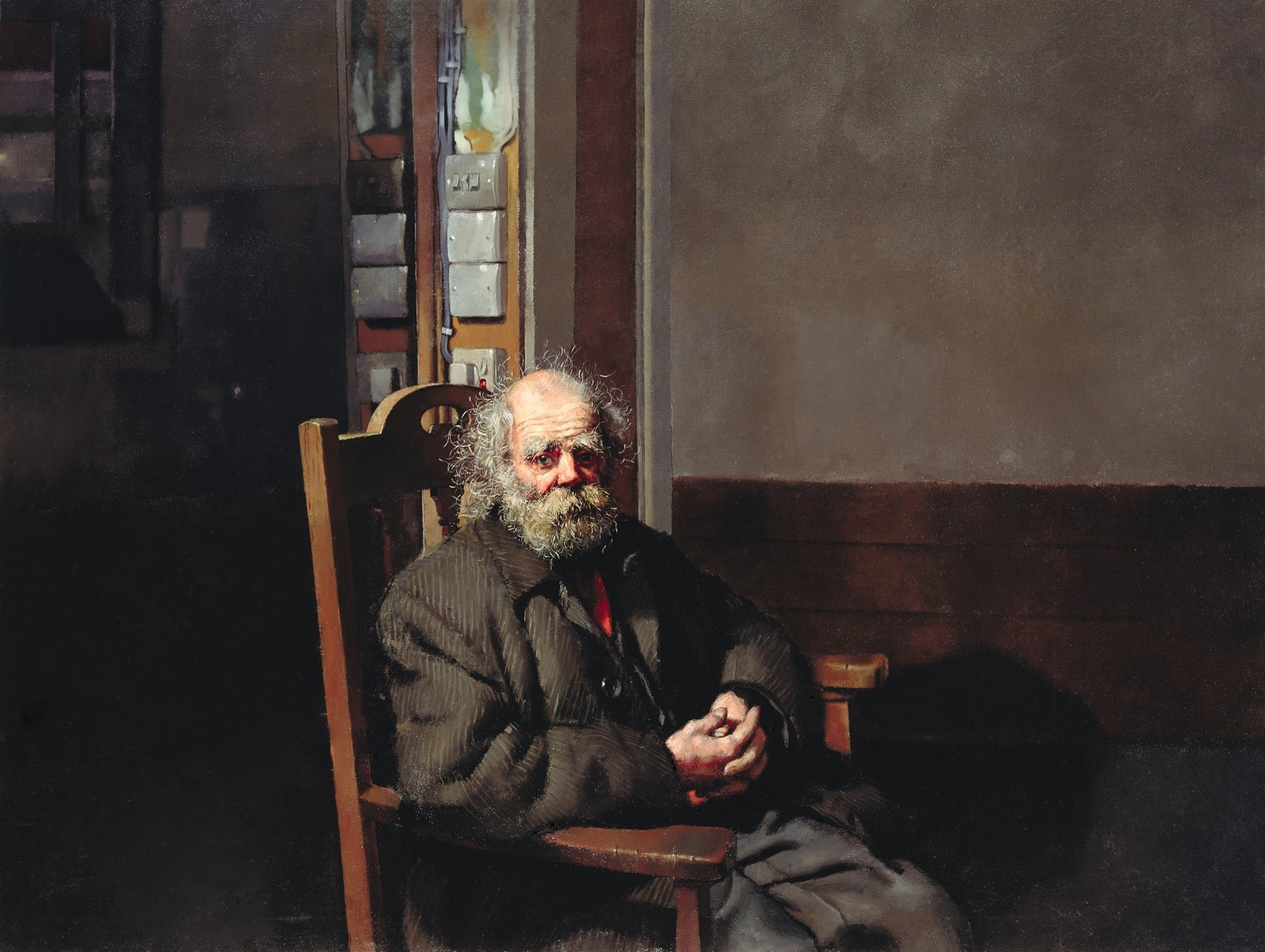

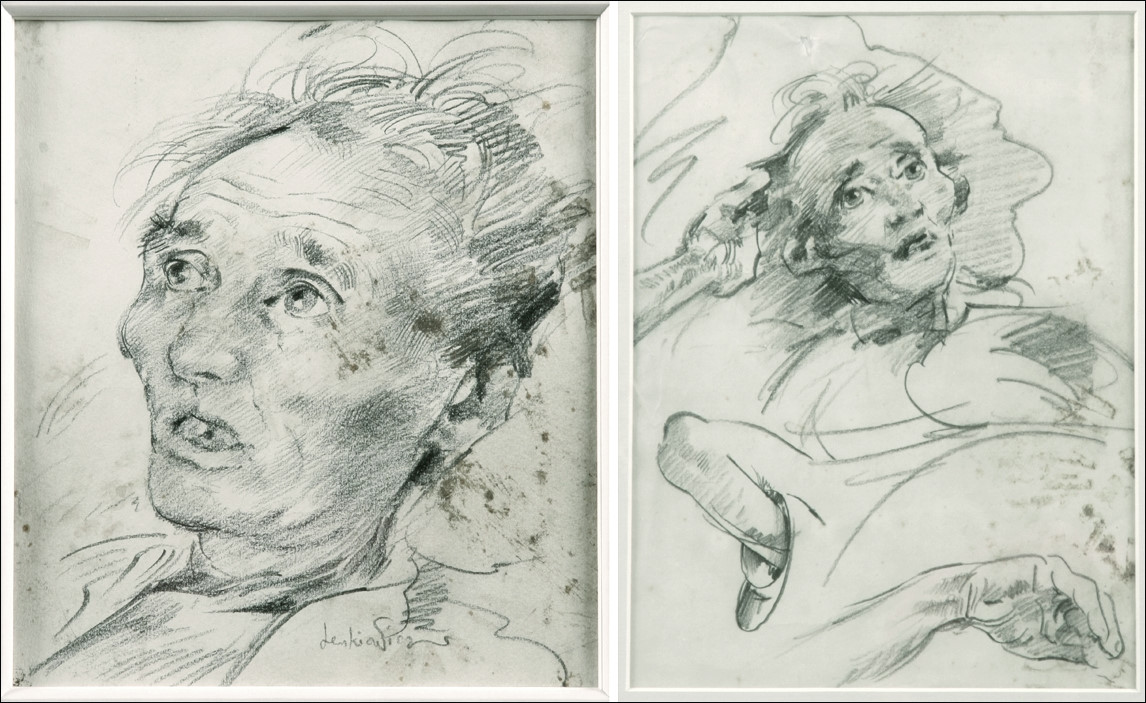

John Kynance – a few minutes before death by cancer. 1973. Inscribed: “vagrant character of rare qualities. Completely out of tune with his thuggish companions”.

Lenkiewicz was inspired by the example of the Italian social activist Danilo Dolci, who exposed the appalling poverty and political neglect in 1960s Sicilian society by recording the oral testimony of its citizens. So Lenkiewicz produced a booklet, Observations on Local Vagrancy, filled with the responses of the vagrants and those professionally involved in their management to a questionnaire on the nature of vagrancy. This approach – of publishing the observations of the sitters, perhaps giving them a public voice for the first time – would be used throughout the exhibitions which Lenkiewicz thought of as “sociological enquiries by visual means”.

On the opening night, the vagrant Albert Fisher, known as ‘Bishop’, unveiled the centrepiece picture, The Apotheosis of Albert Fisher, in which the tramp is seen being escorted up to heaven by a local policeman. Lenkiewicz addressed the guests: “We are gathered here to share a confrontation between the authorities and those who consider themselves vagrant, or who are considered vagrant. That confrontation is designed to establish that there is a vagrancy problem in Plymouth. … This week’s count is 54 people [sleeping rough].” But Lenkiewicz had already been ignored by the local authorities, who scarely accepted that there was a vagrancy problem in Plymouth. In any case, Lenkiewicz believed that hardly any attention is paid to reasoned argument, so he had arranged a trademark visceral surprise for the local dignitaries attending the opening night.

The artist first informed his guests that “Unfortunately, for various reasons, many of the lads who have been ‘skippering’ have not been able to turn up. Many of the authorities have not turned up either.” However, his plan was for the assembled vagrants, who were gathered out of sight of the guests, to flood into the room en masse at a pre-arranged signal. “This they proceeded to do, most of them drunk” said Lenkiewicz, “and, of course, they wrecked the whole evening.”

But the clowns and fools, engaged in their chaotic Dance of Death, who peopled the Vagrancy pictures, had something to teach the more advantaged:

Death makes a fool of life’s joys or purposes, or at any rate appears to. In order to tolerate him he is dressed in the costume of his ambition. Dürer, Holbein and Beham have all recorded him in jester’s apparel. The symbol of the Fool relates to Death insofar as both survive inevitably, they have something innately in common. In one sense death is merely change, a rearrangement; similarly, the Fool, unable to stabilise his situation or mood, reflects the vacillatory undertone of chaos and order, life and death. Unlike the more self-conscious person, the Fool remains unperturbed by his own actions or those of others. (1973)

The pattern was set and Lenkiewicz would now embark on a sequence of exhibitions, shown in his own studios, that looked at “the business of living”. These enquiries were termed The Relationship Series, later known as ‘Projects’, and would have one overriding theme: ‘Attitudes Towards Love’.

Lenkiewicz maintained his connection with the vagrants until the end of his life. Each Christmas Day, he and his associates would provide a seasonal dinner at Plymouth’s bus station, with food donated by local restaurants and cafés.

“It’s very true to say that I would form deeper relationships with some of the ‘cowboys’, dossers, alcoholics, vagrants, call them what you will, than with others. There is something about some of them that is similar to St. John in the desert, a character who interests me more than Jesus. There is something about the desert father, this notion of ‘acidia’, of not looking to the horizon and not needing to be distracted.

“The most startling of them all was ‘The Bishop’, as he was called Albert Edward Ernest Fisher. He was a most extraordinary man: he was an alcoholic; he slept rough most of the time; he was at the Salvation Army for many years. He constructed this posh Oxford accent even though he would say, “Derbyshire born, Derbyshire bred. Strong in the arm, weak in the head.” He would come up with very sweet epithets, particularly when drunk. He was a tragic figure. He would sometimes … start to recite poetry that he had learned by rote at school, some sort of special school for orphans. He could never recite much without tears pouring down his face in the most sentimental way. I asked him to open the Vagrancy exhibition; there was a huge painting called ‘The Apotheosis of Albert Fisher’, now lost, which was about sixty feet long and showed The Bishop rising up into the air with several policemen, another hundred figures at the base. We had a great curtain over it and he was supposed to recite ‘Nicholas Nighe the Donkey’ before revealing the painting. He couldn’t get through it, he started blubbing at the end.

“He was quite an unsentimental character himself, but anything that related to youth, the passing of things and winged creatures would move him. “The albatross sleeps on the wing. I sleep on the wing!” he would say. He could quote large sections of ‘The Ancient Mariner’.”

– R.O. Lenkiewicz, 1997

Having struck up a friendship, Diogenes agreed to look after Lenkiewicz’s studio and his exhibitions. “Shortly before his death, Diogenes made an agreement with Robert that his body would be passed to Lenkiewicz and embalmed.”

He would become the ultimate memento mori (‘remember, you will die’). The deal was not without its controversies.

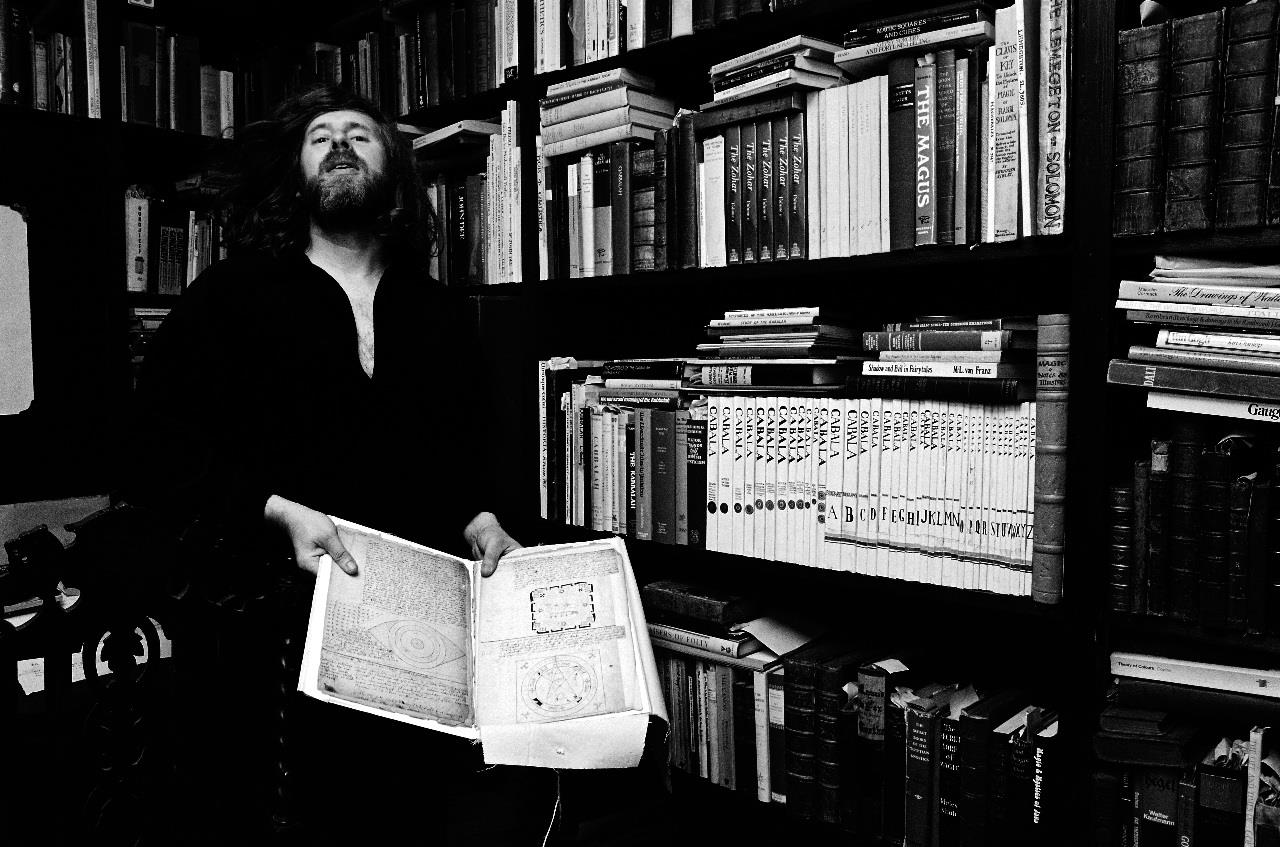

Robert Lenkiewicz, who died in August 2002, seen here in 1982 in the small library at his home in Compton. Photo: Dr Philip Stokes.

On the website of the Robert Lenkiewicz Foundation, Joe Stoneman, a former pupil of Lenkiewicz, quotes from R.O.Lenkiewicz, by Francis Mallett and Mark Penwill. Robert is in conversation with the authors:

I called him Diogenes after the philosopher who lived in a barrel because I found him living in a concrete barrel, a circular container, in the crook of a tree looking down onto Chelson rubbish tip, a precipitous drop, and he had lived in there for nine years. I remember lifting up some of the coats that he slept on to find the whole thing teeming with maggots, so he was a pretty rough and ready character.

He certainly looked like your archetypal medieval scholar, Trithemius von Spanheim say, with a great beard and so on. I became friendly with him and began to visit him up there and do watercolours of him on site. There is a coloured photograph on the front cover of one of the early Telegraph magazines which shows me, young and beardless, drawing him and Diogenes smoking his pipe, which he had smoked since he was twelve! If Diogenes was to be believed, then he had designed and built the Civic Centre building; he had a market garden business with 300 employees; he had won the Grand National once and the Derby twice; he had played for Arsenal; and he had built the Tamar Bridge. And these are only some of his achievements. He lived in my studio and surrounding buildings with me for fifteen years. Then, as he was dying, we had an understanding; he very much had the policy of ‘live while you can and live in clover, when you’m dead, you’m dead all over- — he didn’t much care what happened to the corpse. After he died I kept the agreement, which was to take the corpse, the “vacated premises”, and pass it on to a local funeral parlour who could embalm him effectively, and this was done. And it was done effectively because I have the corpse to this day.

There was a lot of fuss. I kept quiet about it for six or seven weeks, but then someone complained to the health authorities that no one had been buried or cremated under the name of Edward McKenzie. I can remember when I had to register the death they asked me,

“Is he going to be buried or cremated?” And I said, “He’s not going to be buried,” which was exactly the case. They assumed that he was going to be cremated, but actually I hadn’t said so, so that was all sorted.

However, the health authorities came along here some seven weeks later; they got very upset about it and I asked them to leave. I had already made enquiries; there was no property in a body, finder’s keepers, an example of possession being nine-tenths of the law. “It might ’appen in Mexico or in Sicily, Mr Lannevitch, but it ain’t going to ’appen in Plymouth.” I reminded them that it already had happened; there was a Palaeolithic man and two Egyptian mummies in the City Museum—was the objection to mine simply that it was new? I wasn’t even going to exhibit it, yet there were 15,000 exhibited corpses in England alone.

Anyway, they weren’t having it and one thing led to another. For a few weeks the world went mad, the press and so on… I was made to look completely unhinged, whereas originally it was just a rather unusual philosophical artefact whose fate had been agreed upon by myself and the artefact. Eventually, there had been so many break-ins in different studios and at my house to look for the corpse that it got rather fatiguing. So with a close friend of mine we arranged, with the help of a couple of journalists, that the corpse would arrive here at a certain time and for the health authorities to hear about this. My friend drove this big lorry and half a dozen associates of mine placed this large box outside the front door here. There were about seven or eight strange people outside, very smartly dressed, pretending to take photographs of the mural like innocent tourists, even though it was freezing weather. We’d also been informed that round the corner a hearse had mysteriously appeared.

We let the health authorities freeze there for a couple of hours because we knew they couldn’t seize the corpse on the Queen’s highway; they would have to seize it on my property. It was then brought in and they did indeed burst in very aggressively, held a couple of people up against the wall and took some kind of crowbar to the box and lifted the lid. I sat up, wrapped in a duvet with a hot water bottle. I had a large sign in Latin, saying “Verumne tenet TSW” — “Does local television tell lies?” — and then “HABEAS CORPUS”. Well, they were quite apoplectic. This incident was reported in the local papers along with all the other nonsense and they were embarrassed into silence. They left me alone from then on.”

Your purpose in the experiment?

“I was building up a library on the theme of death and I thought that at one point it would be very nice if the library room on death had artefacts that related to the theme. I had all kinds of things; an unusual collection of skulls and objects of one kind or another that related to death, and felt there couldn’t be anything more thought provoking than the corpse of a human being. Had I had my wits about me earlier on, I would have much preferred my mother, but Diogenes was fine. It was surprising how many visits and letters I got from people offering me the same service; that is to say, that they would also like to be embalmed.”

“There was a phrase I used: that one can be very struck by the total presence of the corpse and the total absence of the person, particularly if one knew the person. This is the primary sensation, in my view, that one gets in viewing a dead body, and I’ve seen many—the total absence of the person running parallel with the total presence of the corpse. And the corpse has menace, has potential for decay and putrefaction, almost like an attacking machine, but the person has curiously vapourized. I’m not making claims for self or soul or essence or

spirit; I regard these all as poetic metaphors. But in witnessing a corpse one can certainly understand how these poetic metaphors arise.”Diogenes used to look after the studio and the exhibitions. Can you explain more about the actual set-up of the premises at the time? I don’t think it was quite the whole building as it is now?

“It started downstairs in the front window from 1969 onwards. And derelict buildings in the area that I would break into and take over. But slowly I spread through the whole building. That in itself is a long story with all kinds of chicaneries, but eventually I took over the whole building and decided to open all the rooms as spaces for presenting the Projects.

When you ascended the first flight of stairs there was a kind of arched opening where the door had been removed and Diogenes sat there, by a desk. There was a 10p entrance fee; Diogenes would be sitting there and would go “Ar… Ar… Ar.” That’s about it really. Sometimes, they’d ask him a question and he’d go, “Ar… Ar.” He did it for fifteen years and he was very popular, but there were times when I wasn’t sure whether people were coming in to see Diogenes or coming in to see the exhibition. They were certainly very surprised by him as

they came up the stairs—this scrawny, miniature Father Christmas.

Robert’s 1977 diary notes that he purchased a new camera and also published a print of ‘The Barbican Mural’, which is being held by “artist’s assistant” Diogenes. Robert said “He lived in my Barbican studio and sundry other buildings with me for fifteen years. There was a 10p entrance fee; Diogenes would be sitting there and would go “Ar … Ar … Ar.” That’s about it really.

Diogenes and Jon Cox ‘Diaghileff’ minding Lenkiewicz’s Barbican exhibition rooms on 26.08.1977. The painter’s exhibition on the theme of Jealousy was being shown that month.

Possibly the most impressive advertising hoarding ever conceived? The view of the blank warehouse wall c.1971 on which Robert proposed to paint his famous mural. The painter’s studio at No. 225 The Parade was renamed ‘The Portrait Painter’ whilst the mural was in progress.

The Barbican Mural adjacent to Robert’s studio was completed in July 1972. Its 3000 sq ft area “concerns itself with metaphysical ideas current in England during the period 1580-1620”. The painter’s notes continue “These ideas cover the following activities: Philosophy; Alchemy; Cabala; Ceremonial Magic; the symbolic aspects of poetry, music and art; the cult of melancholy, chivalry, and similar allegorical trends.”

The Plymouth Herald has a delightful anecdote on the artist’s life:

In 1970, Lenkiewicz rented studio space at No. 25 The Parade (where SWIB is now based) and opened The Portrait Painter. Then in 1971, he began work on the Barbican Mural on the wall of the adjacent warehouse.

Some 3,000 square feet in extent, the mural deals with ‘The Influence of Jewish Thought on Elizabethan Culture, 1580-1620’ and was completed in the summer of 1972. On April Fool’s Day, as a result of one of his regular disputes with the local Council, the artist whitewashed over it and replaced it with three flying ducks!

Former Labour Party leader Plymouth-born Michael Foot (July 23 1913 – March 3 2010) being painted by Lenkiewicz in hgis studio. May 15, 2001

Via the wonderful Lenkiewicz Foundation, Joe Stoneman

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.