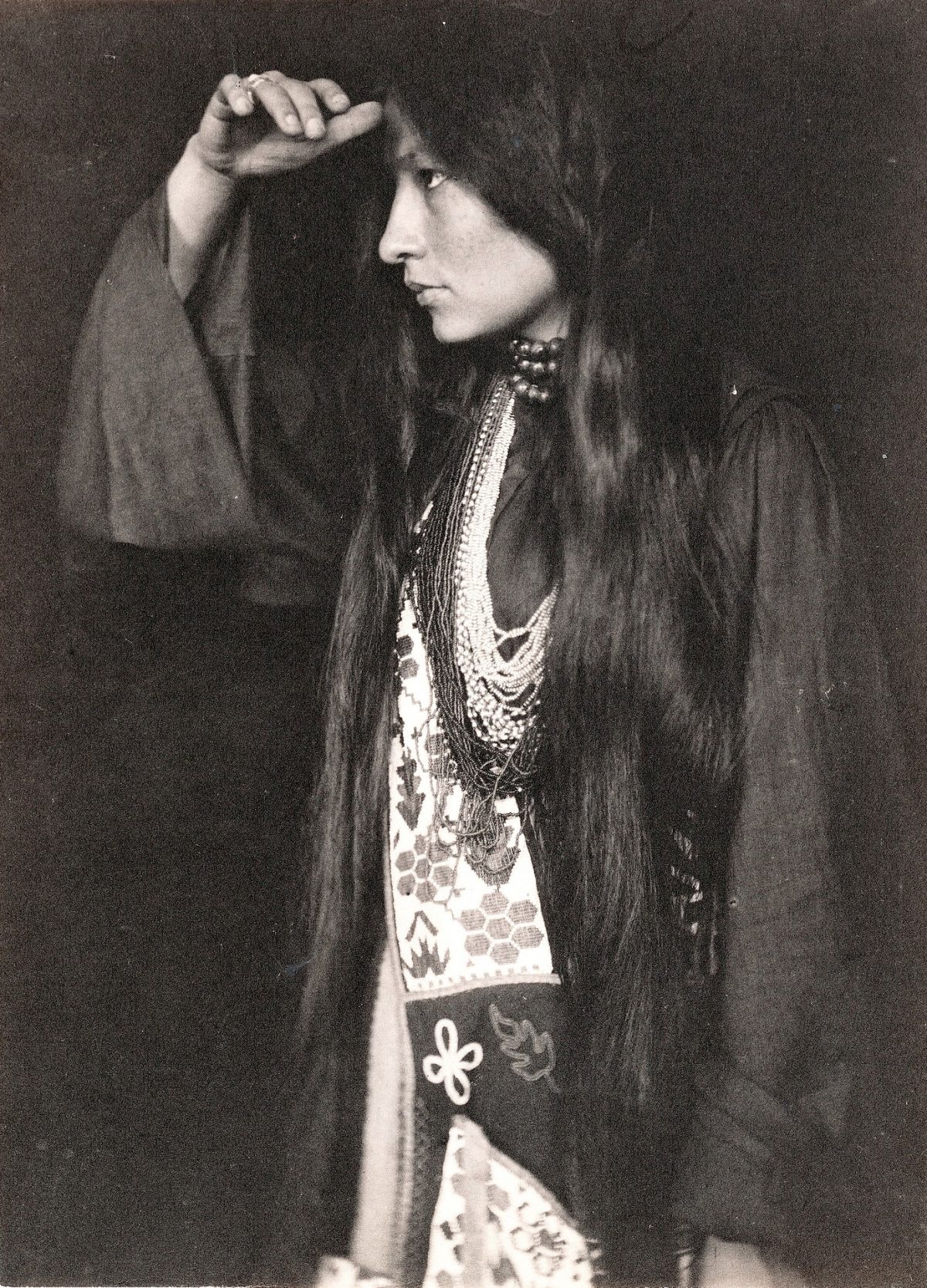

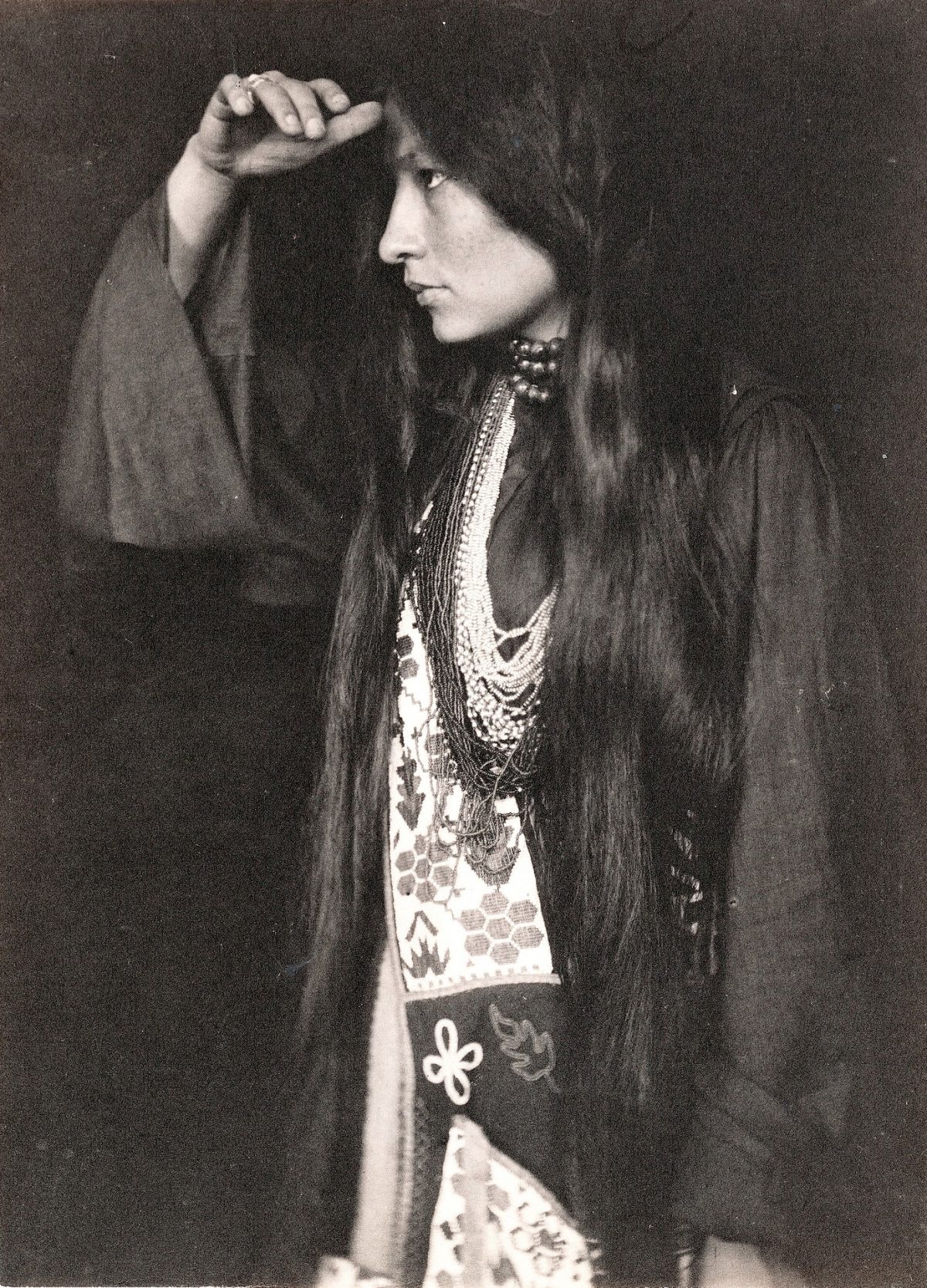

Zitkala-Sa by Gertrude Käsebier 1898

“The contributions of Asian American, Latina, and Native American suffragists are just beginning to be examined by scholars,” writes the Library of Congress, a full century after the passage of the 19th Amendmentto the U.S. Constitution in 1920, “but there is still much work to be done regarding all women of color.” Part of the issue is that feminisms of the past thought of themselves as working on behalf of all women, without including all women in their deliberations. The legislation “ended nearly a century of protest, which kicked off at the historic Seneca Falls Convention,” writes Carl Samson, but it “had very little effect on those outside the categorization of upper and middle-class white women.”

The Seneca Falls Convention, which took place in July of 1848, is generally “heralded as the first American women’s rights convention,” the Library of Congress notes, and credited as a founding event for the suffrage movement in the U.S. The two-day conference, “held in the Wesleyan Chapel in Seneca Falls, New York,” attracted 300 women at its inaugural meeting—including, of course, convention organizer Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who, along with her husband Henry B. Stanton, was a well-known abolitionist and campaigner for various 19th century reform movements.

Zitkala-Sa Red Bird

“In fact,” the LoC points out, “all five women credited with organizing the Seneca Falls Convention were also active in the abolitionist movement.” It is odd, then, that “no known African American women attended Seneca Falls.” This was also mostly the case eleven years earlier at the first Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women, held in New York City on May 9, 1837, where only five black women are recorded in attendance, despite conference organizer Angelina Grimke’s statement, “it is all important that we begin right and I know no way as likely to destroy the cruel prejudices that exist as to bring our sisters in contact with those who shrink from such intercourse.”

Anna Julia Cooper

Mabel Ping-hua Lee

Of all the “cruel prejudices” that prevented women of color from attending conventions, those that abolitionists did not address often enough were the economic barriers that prevented women without means from traveling and lodging. Black women who did travel to attend large meetings faced hostility, segregation, and discrimination that discouraged them from considering the journey in subsequent years as the Anti-Slavery Convention moved to different cities until 1840. Implicit in the appellation “American Women” was a very specific idea of who counted as an American woman.

Sofia Reyes de Veyra

These facts do not mean, however, that women of color didn’t strenuously advocate in their own societies for the right to fully participate in democracy, through voting and other rights due everyone. One critical difference is that many of these suffragists refused to be drawn into a divide-and-conquer strategy. They “believed in universal suffrage,” notes the LoC, “voting rights without regard to race, gender, education, or economic status.” Those conditions were not met by the 19th Amendment.

Adelina “Nina” Otero-Warren

Achieving full suffrage for women would fall to activists like Anna Julia Cooper (top) who articulated a black feminist ethic in her 1892 book A Voice from the South; Yankton Dakota Sioux Zitkála-Šá (also known as Gertrude Simmons), who “supported women’s rights and civil rights for Native Americans, including the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act, which gave Native Americans the right to vote in the United States”; Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, a member of the New York Women’s Political Equality League, who “rode on horseback in the 1912 New York City parade in support of women’s suffrage,” but who was unable to vote even after 1920 due to the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act; Sofia Reyes de Veyra, who fought for the women’s right to vote in the Philippines, a right won in 1937; and Adelina “Nina” Otero-Warren, who organized support among Spanish- and English-speaking communities in her state of New Mexico, where she later served as the state’s first female government official.

Milagros Benet de Newton

Other women, like conservative Puerto Rican suffrage leader Milagros Benet de Newton, above, fought for a more limited franchise, supporting voting rights for only educated women, though “other suffragists in Puerto Rico, especially those with ties to the labor movement, advocated universal suffrage.” Congress gave the vote to literate women on the island in 1929 and all women in 1932, though Puerto Ricans of all genders are still barred from voting in presidential elections. As the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment’s ratification on August 18, 1920 approaches, those celebrating the event should also remember the women who had to keep fighting afterward, and continue to struggle, for citizenship and voting rights.

Zitkala-Sa by Gertrude Käsebier 1898

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.