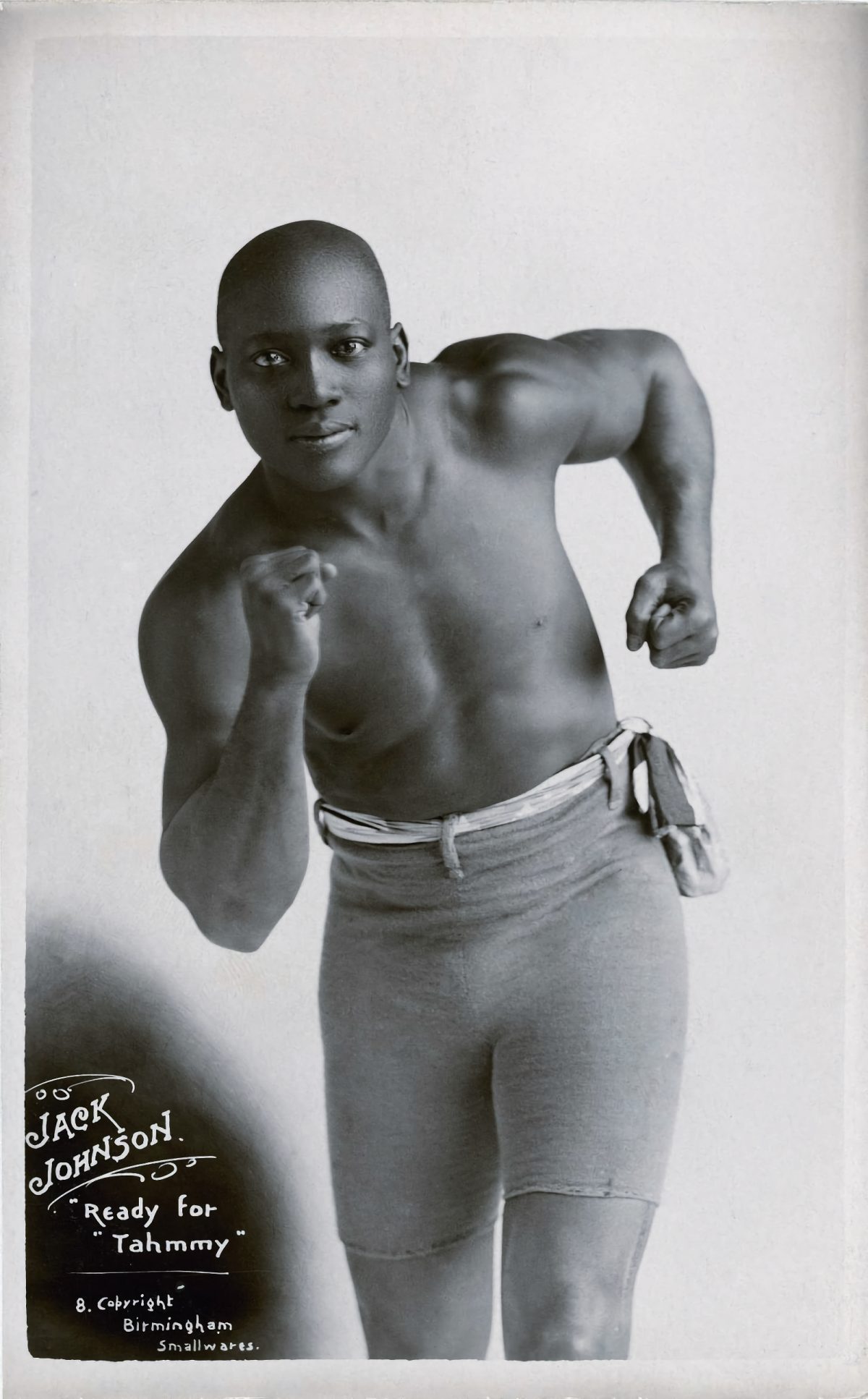

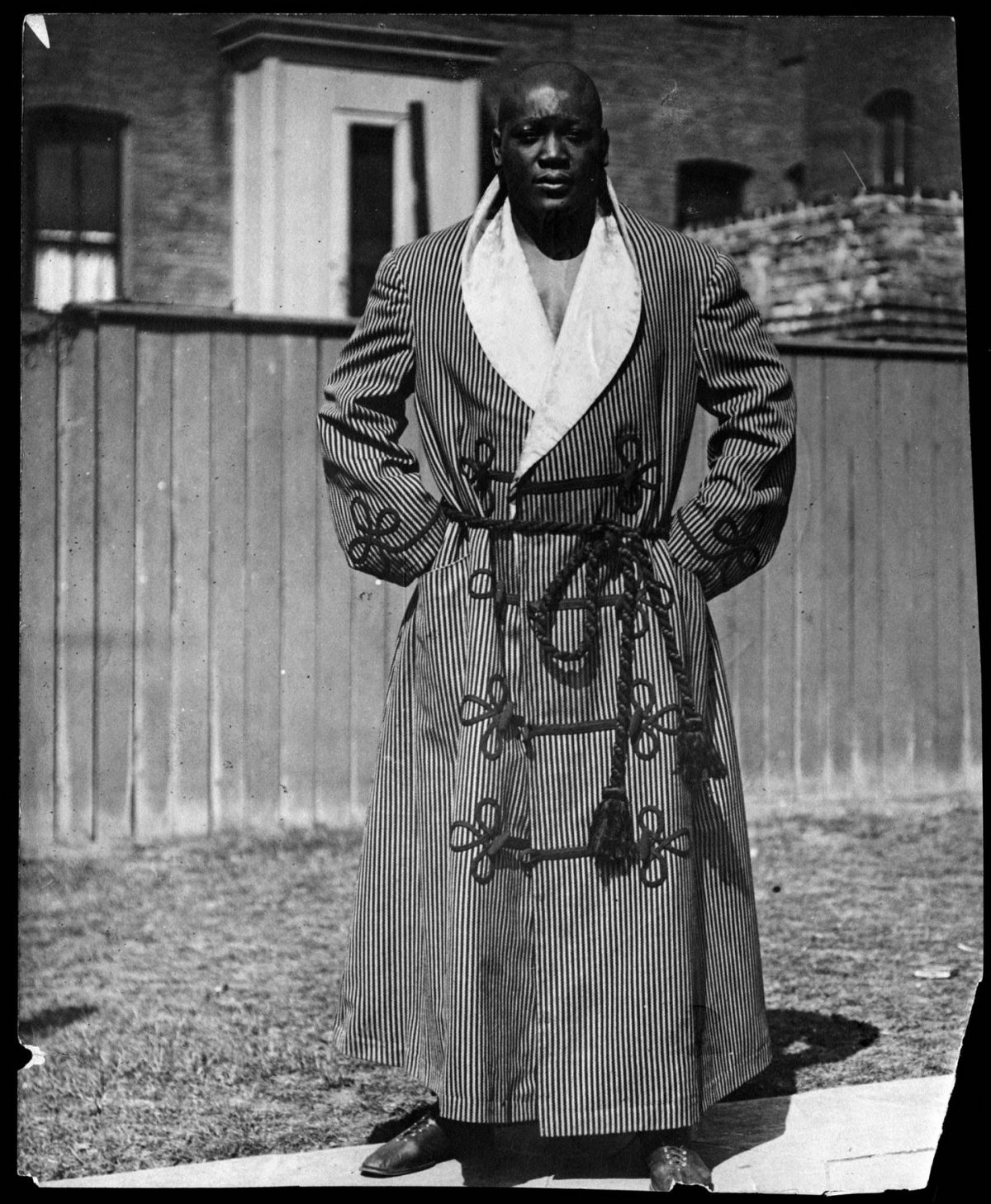

During the summer of 1912, the man who at the height of the Jim Crow era had become less than four years previously the first black world heavyweight boxing champion, opened Cafe de Champion – a “Black and Tan” restaurant and nightclub in the Bronzeville district of Chicago. The club was decorated in an ostentatiously luxurious style and featuring electric fans to cool the interior, said to be some of the first in the city. Johnson’s wife Etta ran the sophisticated restaurant downstairs where the waiters all wore white gloves while the music and dancing took place in the ‘Pompeiian Room’ decorated in a Roman style.

The top floor of the three storey building became the Johnsons’ apartment and it was where Etta, after two previous attempts, took her own life in September 1912. She shot herself in the head while the partying took place below. The 33 year old former Brooklyn society woman had a history of depression but any mental problems could only have been exacerbated after she was hospitalised the previous year when Johnson severely beat her up suspecting her of having an affair. Johnson’s violence and constant infidelity could only have helped cause the suicide attempts.

Jack Johnson, top left, at his wife Etta’s funeral on Sept. 14, 1912, with his mother-in-law, Mrs. David Terry, center.

A month later and already with a new beau on his arm – Lucille Cameron, an 18-year-old prostitute from Milwaukee – Johnson was forced to quit the premises. At about the same time Johnson was arrested on the grounds that his relationship with Lucille Cameron violated the Mann Act for transporting a woman across state lines for immoral purposes. Cameron, soon to become his wife, refused to cooperate and the case fell apart. The authorities were out to get the heavyweight boxer and less than a month later Johnson was again arrested on similar charges. Despite the fact that the incidents this time took place before the passage of the infamous Mann Act. He was convicted by an all-white jury and sentenced to a year and a day in prison.

Johnson skipped bail and quickly left the country, joining Lucille in Montreal before sailing to France. For the next seven years, they lived in exile in Europe, South America and Mexico.

On July 20, 1920 Johnson returned to the US by surrendering himself to federal agents at the Mexican border. He was sent to the United States Penitentiary, Leavenworth until he was released on July 9, 1921.

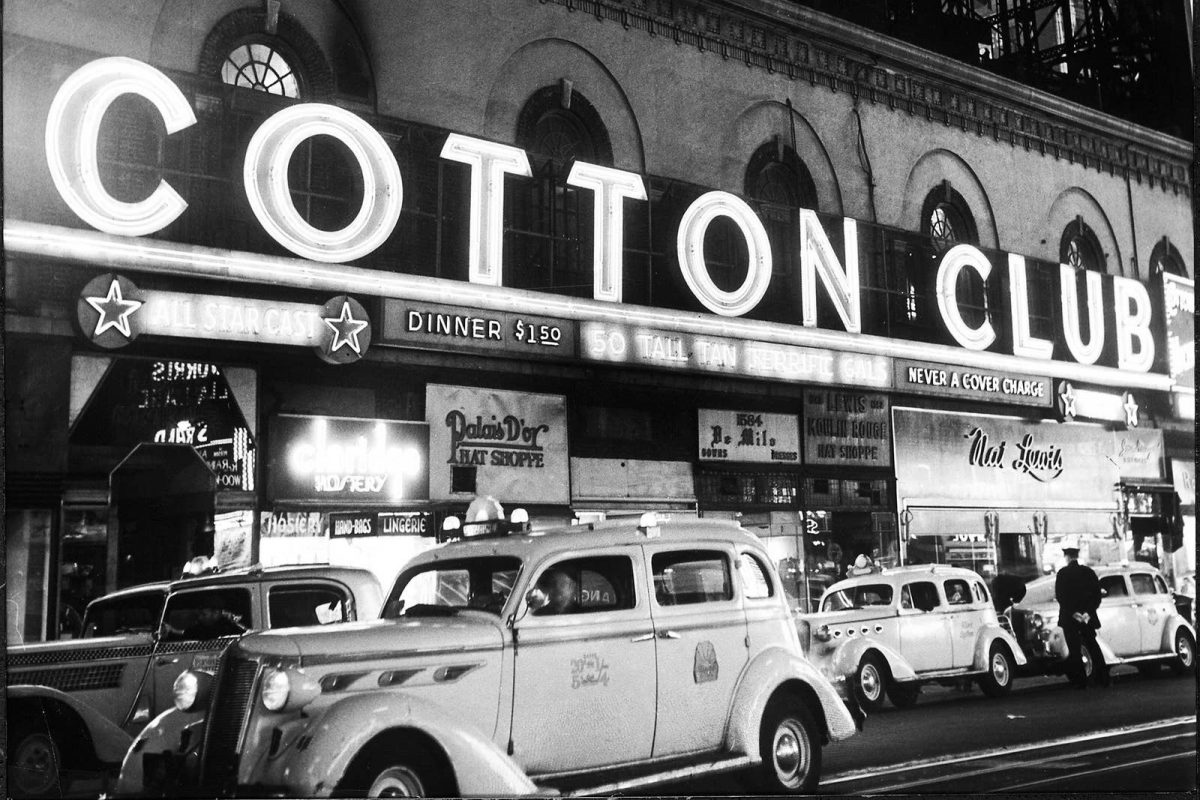

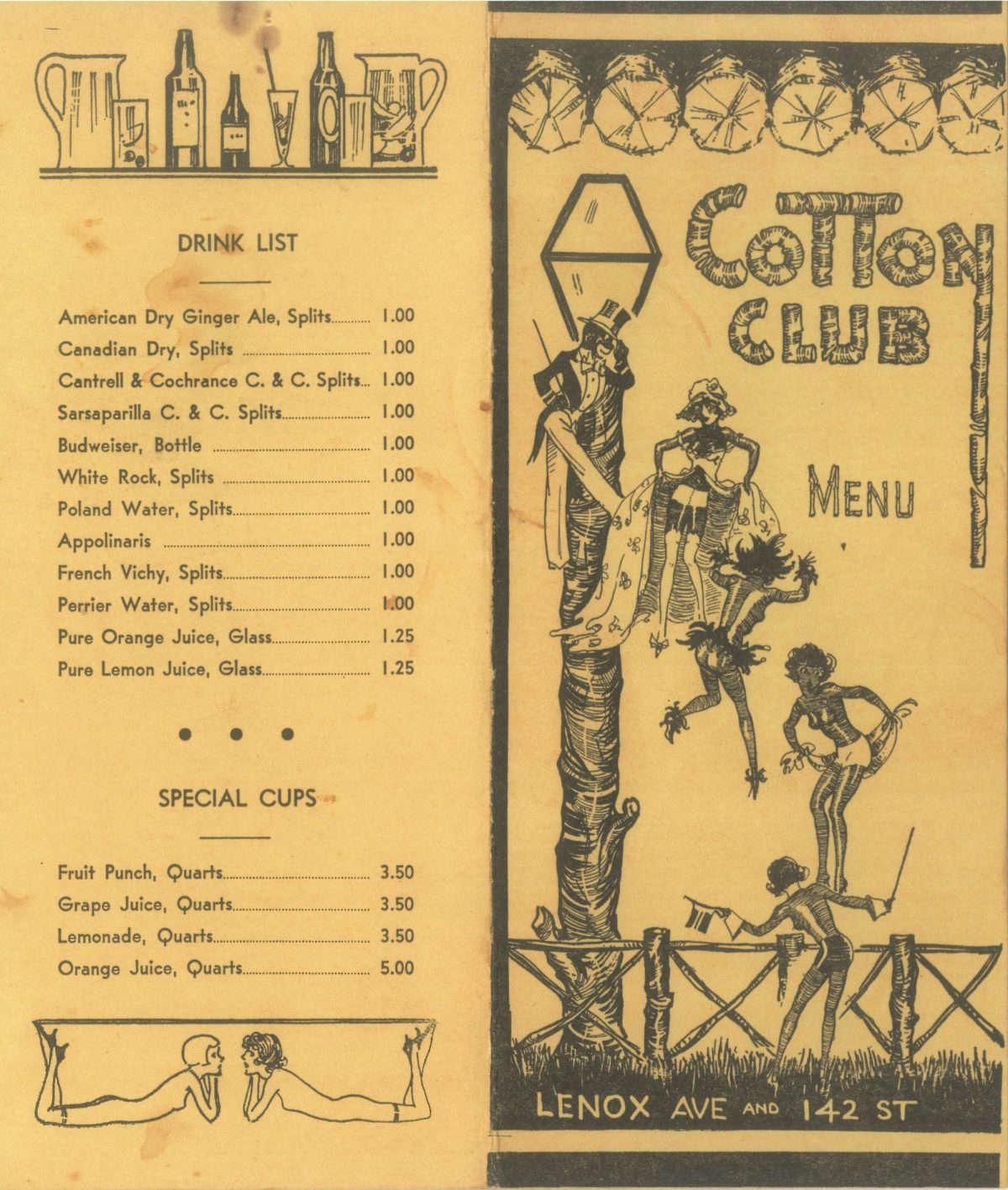

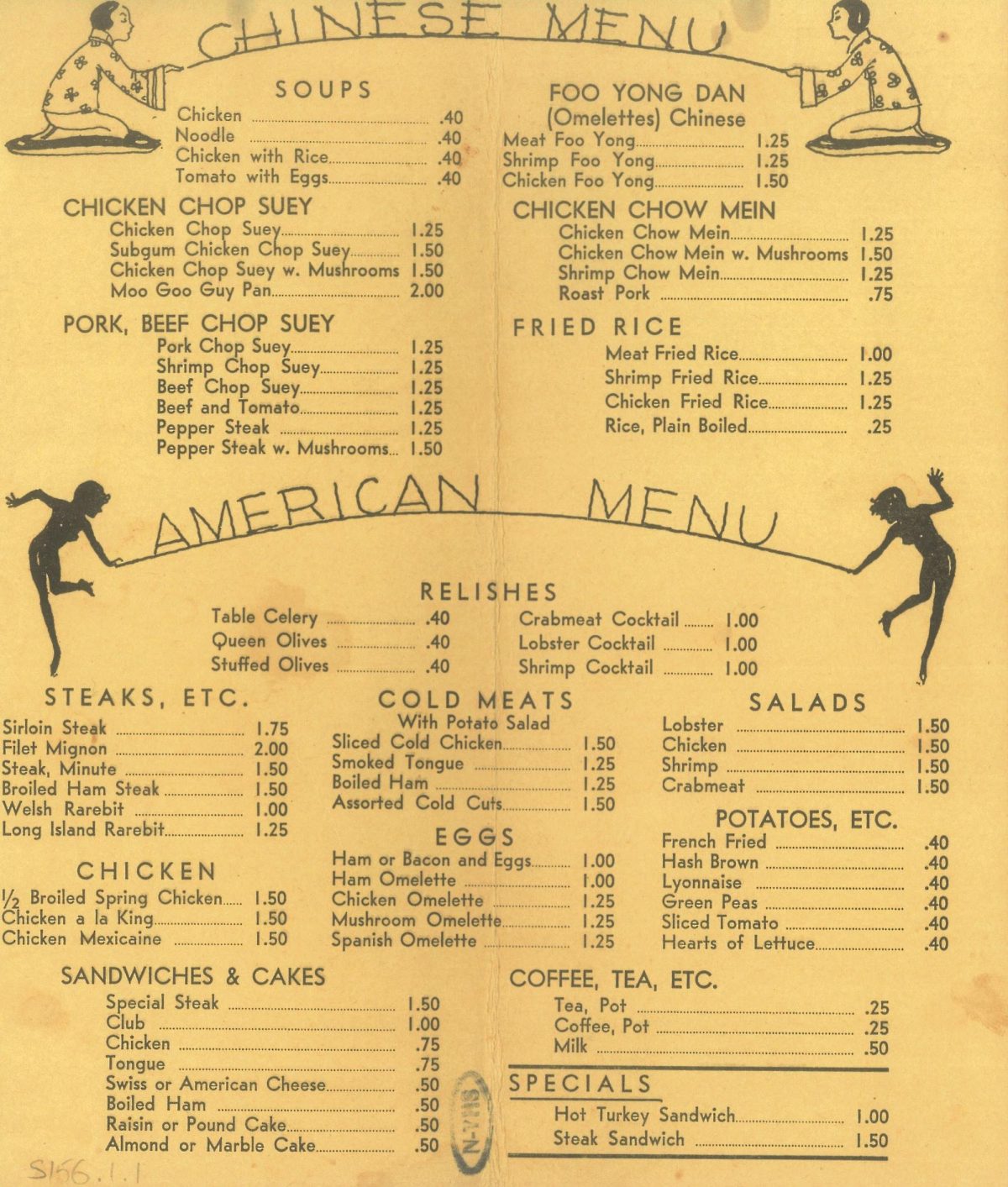

While he was still at the penitentiary Johnson opened a new club at Lenox Avenue and West 142nd Street in Harlem called the Club Deluxe. In 1922 he sold it to the gangster Owney Madden who renamed the nightspot – “The Cotton Club” a name designed to appeal to a white audience – the only clientele permitted until 1928 – but who nonetheless came in droves to see the risqué Harlem culture.

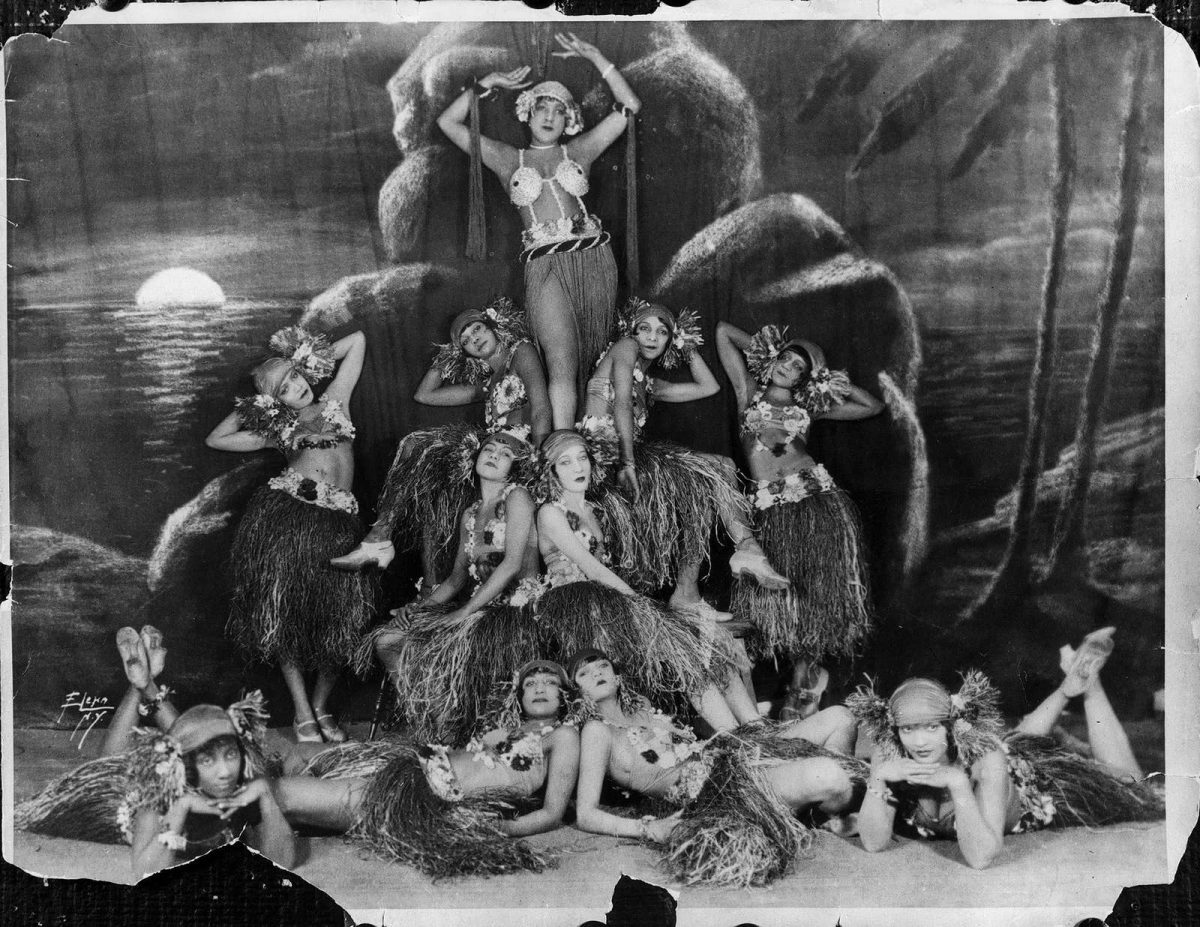

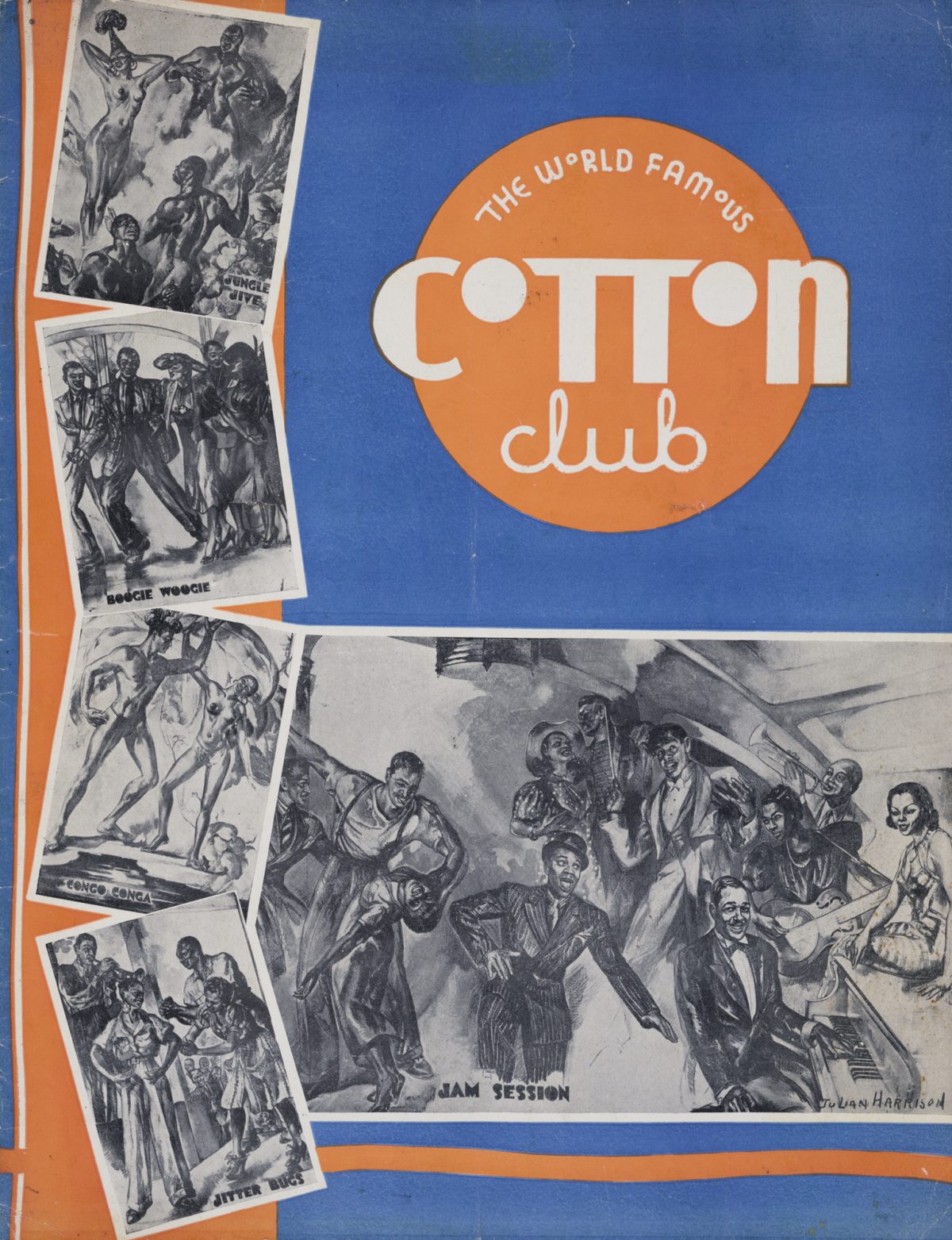

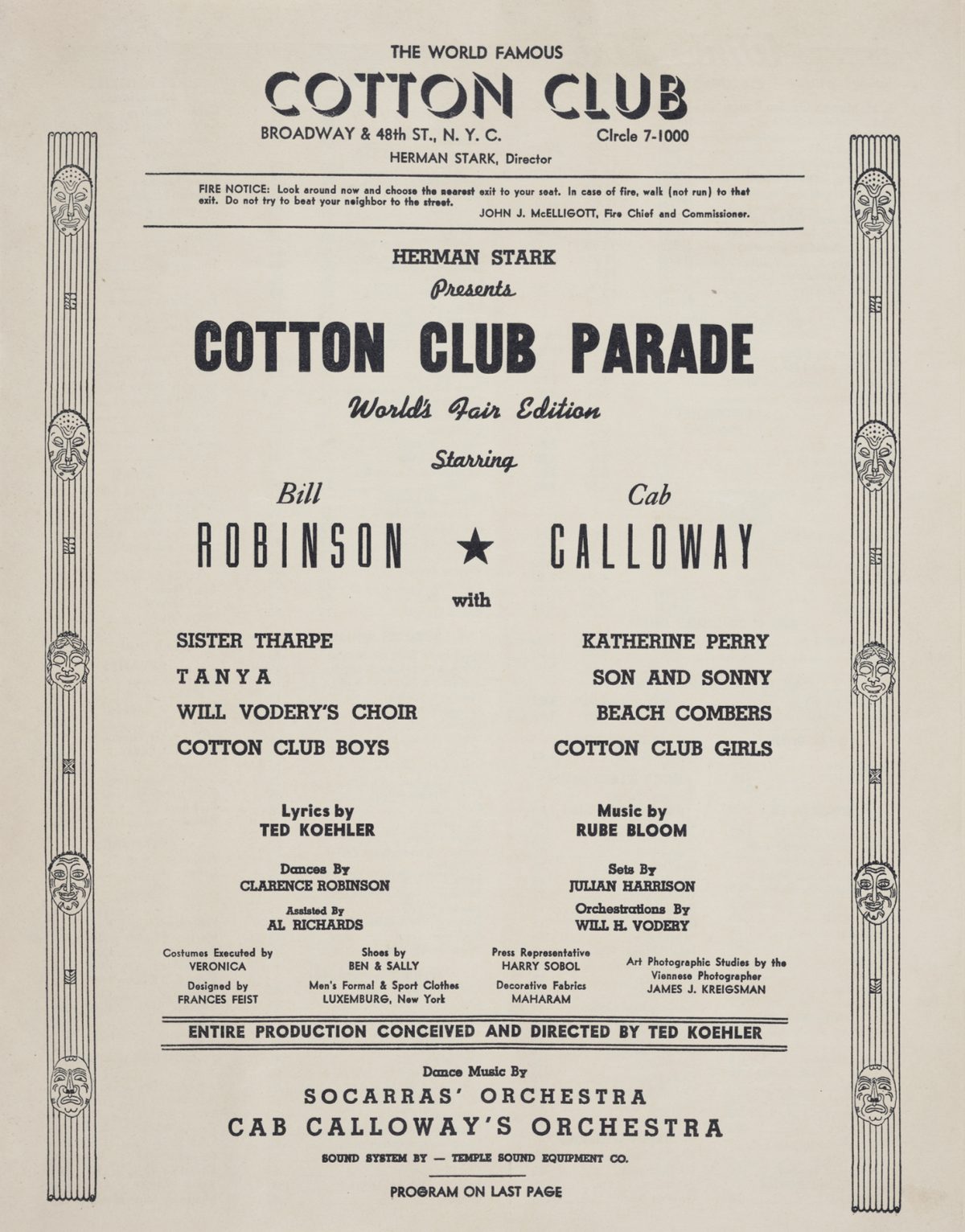

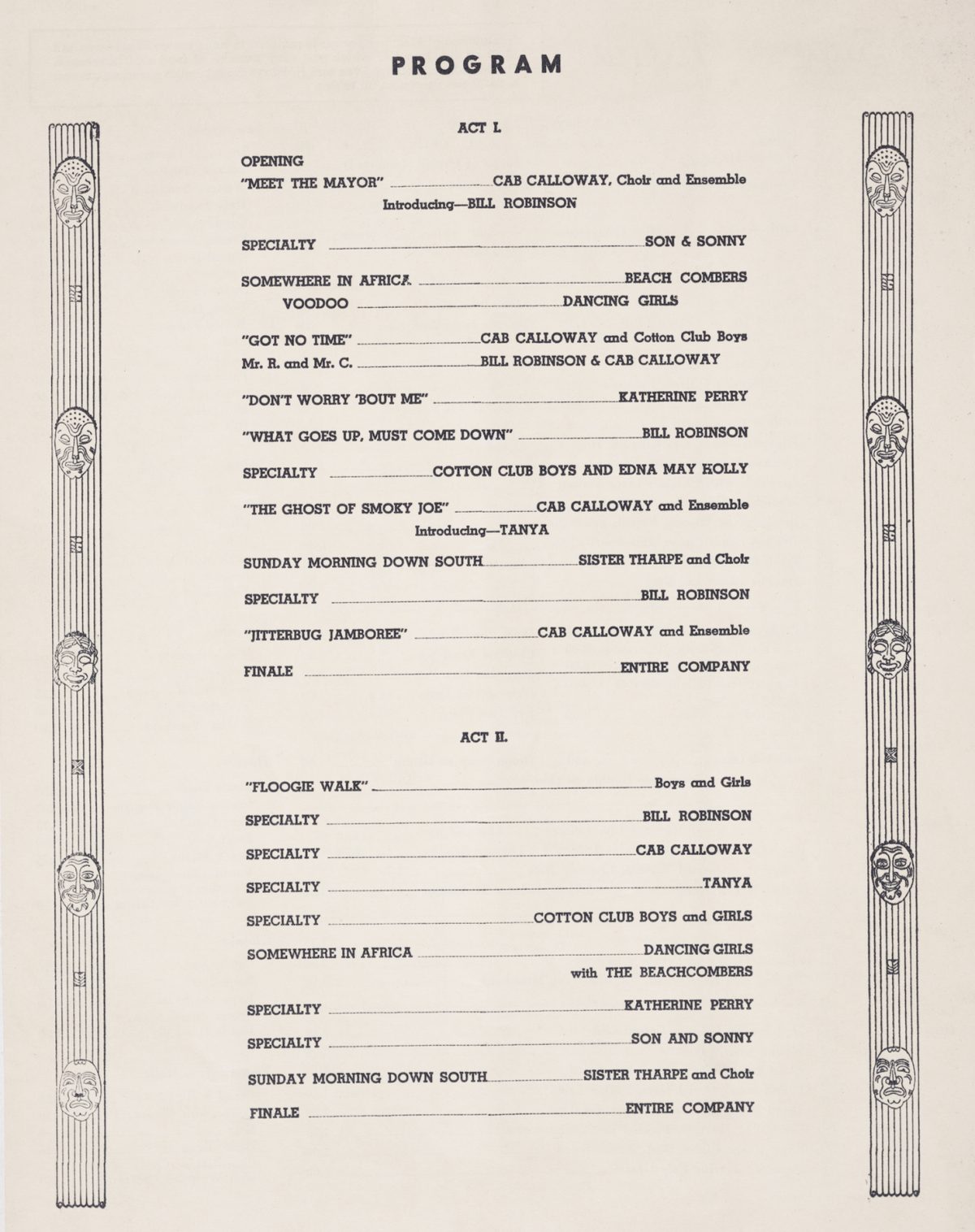

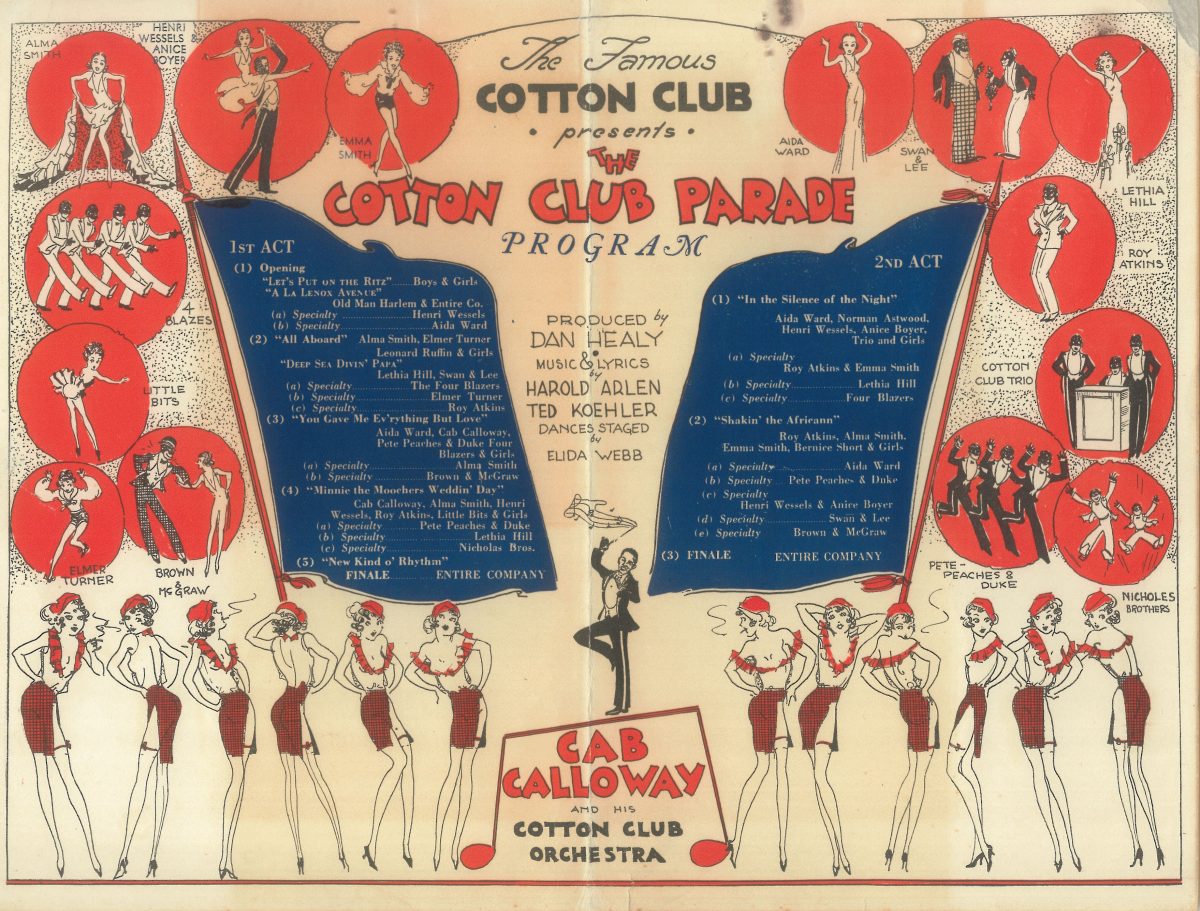

The audience may have been all white but they came to see some of the most popular black entertainers of the day (many of whom are internationally famous to this day), including musicians such as Fletcher Henderson, Duke Ellington, Chick Webb, Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Fats Waller; vocalists Adelaide Hall, Ethel Waters, Cab Calloway, Bessie Smith, the Dandridge Sisters, The Mills Brothers, Nina Mae McKinney, Billie Holiday, Lena Horne, and dancers such as Katherine Dunham, Bill Robinson, The Nicholas Brothers, Charles ‘Honi’ Coles, Leonard Reed, Stepin Fetchit, the Berry Brothers, The Four Step Brothers, Jeni Le Gon and Earl Snakehips Tucker.

In 1927 Andy Preer, the leader of the house band the Cotton Club Syncopators, died and Duke Ellington and his orchestra were hired as replacements. Duke Ellington never looked back.

Responding to local protests, the club’s management allowed black patrons for the first time late in 1928. It didn’t make much difference, the prices were kept prohibitively expensive to all but the very rich, and the club’s audience remained virtually all white.

A look at the interior of the Broadway Cotton Club circa, during an New Year’s celebration, 1937, with Cab Calloway conducting.

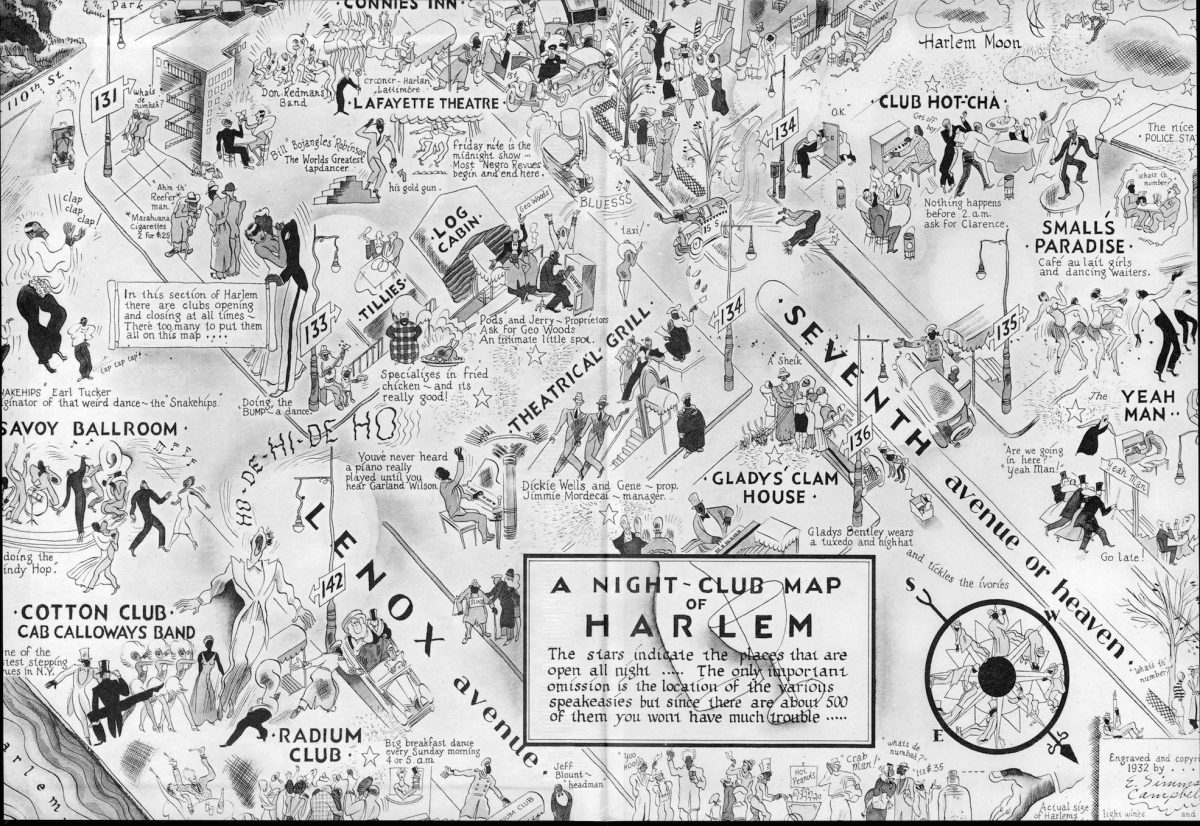

A map from 1932 of the Harlem nightclub scene, featuring the Cotton Club, Small’s Paradise, Connie’s Inn, the Savoy Ballroom and more….

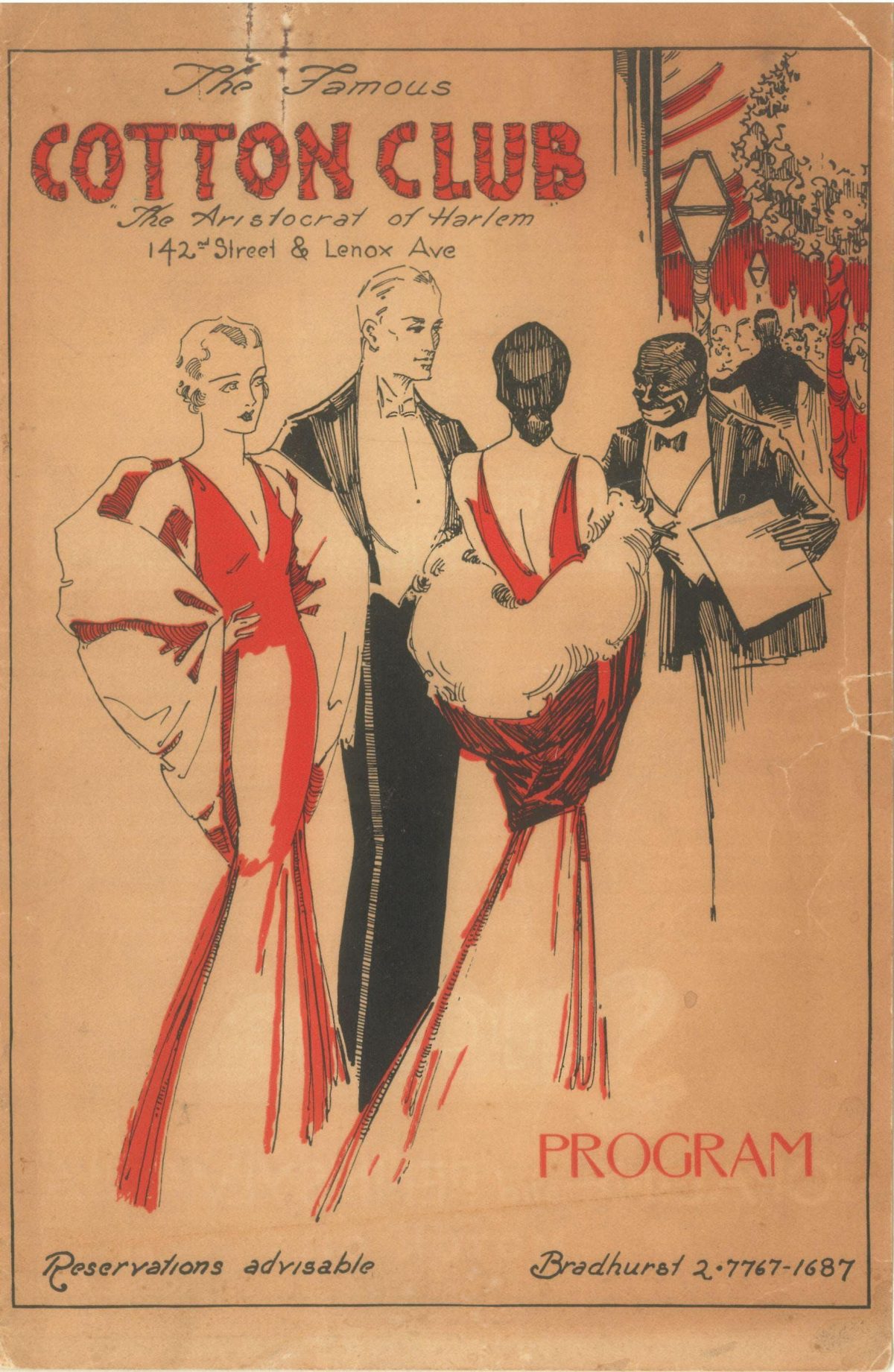

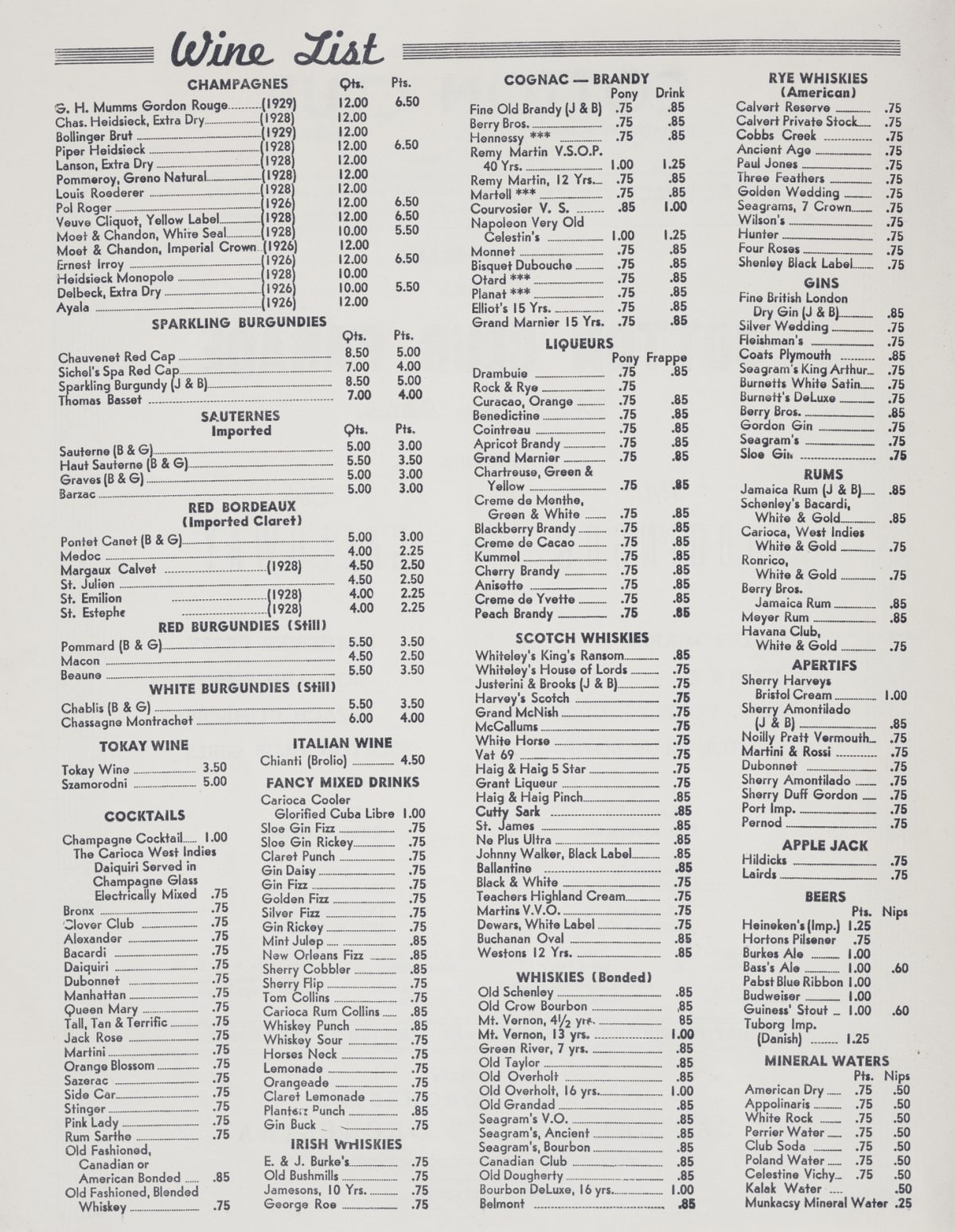

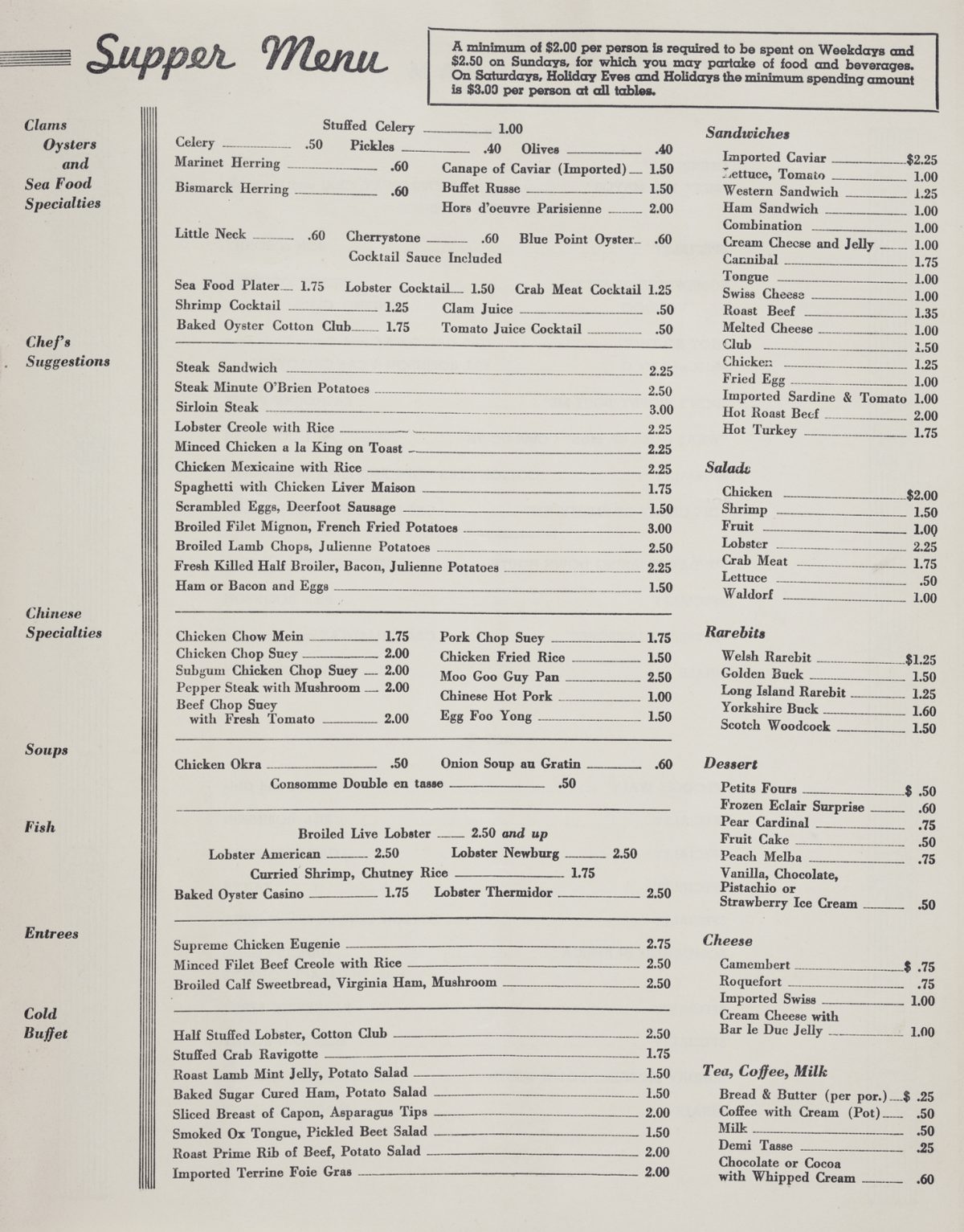

The Cotton Club Parade Program. The Famous Cotton Club- the Aristocrat of Harlem. New York- ca. April 1932.

One man who came to the Cotton Club was the writer and social activist Langston Hughes although the visit left a ‘distinctly bitter taste in my mouth’. In his autobiography he writes of how the white and rich clientele treated Harlem merely as a location for a fashionable evening:

“Nor did ordinary Negroes like the growing influx of whites toward Harlem after sundown, flooding the little cabarets and bars where formerly only colored people laughed and sang, and where now the strangers were given the best ringside tables to sit and stare at the Negro customers–like amusing animals in a zoo.

The Negroes said: “We can’t go downtown and sit and stare at you in your clubs. You won’t even let us in your clubs.” But they didn’t say it out loud–for Negroes are practically never rude to white people. So thousands of whites came to Harlem night after night, thinking the Negroes loved to have them there, and firmly believing that all Harlemites left their houses at sundown to sing and dance in cabarets, because most of the whites saw nothing but the cabarets, not the houses.”

In 1931 Ellington and his orchestra left the club and were replaced by Cab Calloway’s Missourians. Calloway, like Ellington, took his chance with both hands establishing himself as a major figure in jazz during his Cotton Club years. Calloway’s Missourians remained the house band until 1934, when they were replaced by Jimmie Lunceford’s acclaimed swing band.

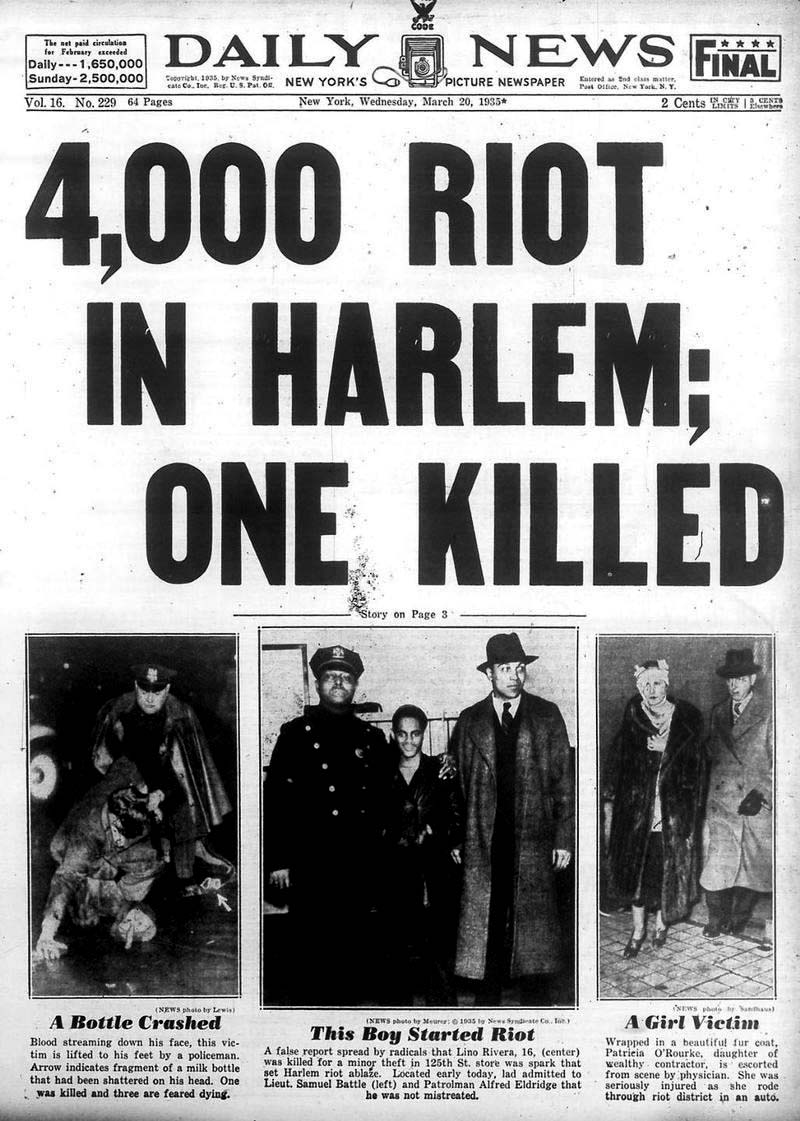

Following the Harlem ‘race riots’ in 1935, the club was closed after much of their former audience perceived that the area had become dangerous. The Cotton Club reopened downtown in 1936, at 200 West 48th Street, where it remained until its final closing in 1940.

In 1924, two years after selling the Club Deluxe to Owney Madden, Johnson and Lucille were divorced on the uncontested charge (for good reason) of Johnson’s infidelity. The following year Johnson met Irene Pineau at a race track in Aurora, Illinois. The were married in August 1925 and she remained at the boxer’s side until the end of his life.

Less that a year after his last boxing match at the age of 67 on November 27, 1945, fighting three one-minute rounds in a benefit fight for U.S. War Bonds, Johnson died in a car crash near Franklinton, North Carolina. Hitting a telegraph pole after driving angrily away from a segregated diner that had refused to serve him. Irene buried him in the Graceland Cemetery in Chicago, next to his former wife Etta Duryea.

A reporter at the funeral asked Irene why she loved Johnson so and she said, “I loved him because of his courage. He faced the world unafraid. There wasn’t anybody or anything he feared.”

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.