“Your wolves have more wit than your maester,” the wildling woman said. “They know truths the grey man has forgotten.” The way she said it made him shiver, and when he asked what the comet meant, she answered, “Blood and fire, boy, and nothing sweet.”

— George R.R. Martin, A Clash of Kings, A Song of Ice and Fire, #2

Domina capillorum (Sol)

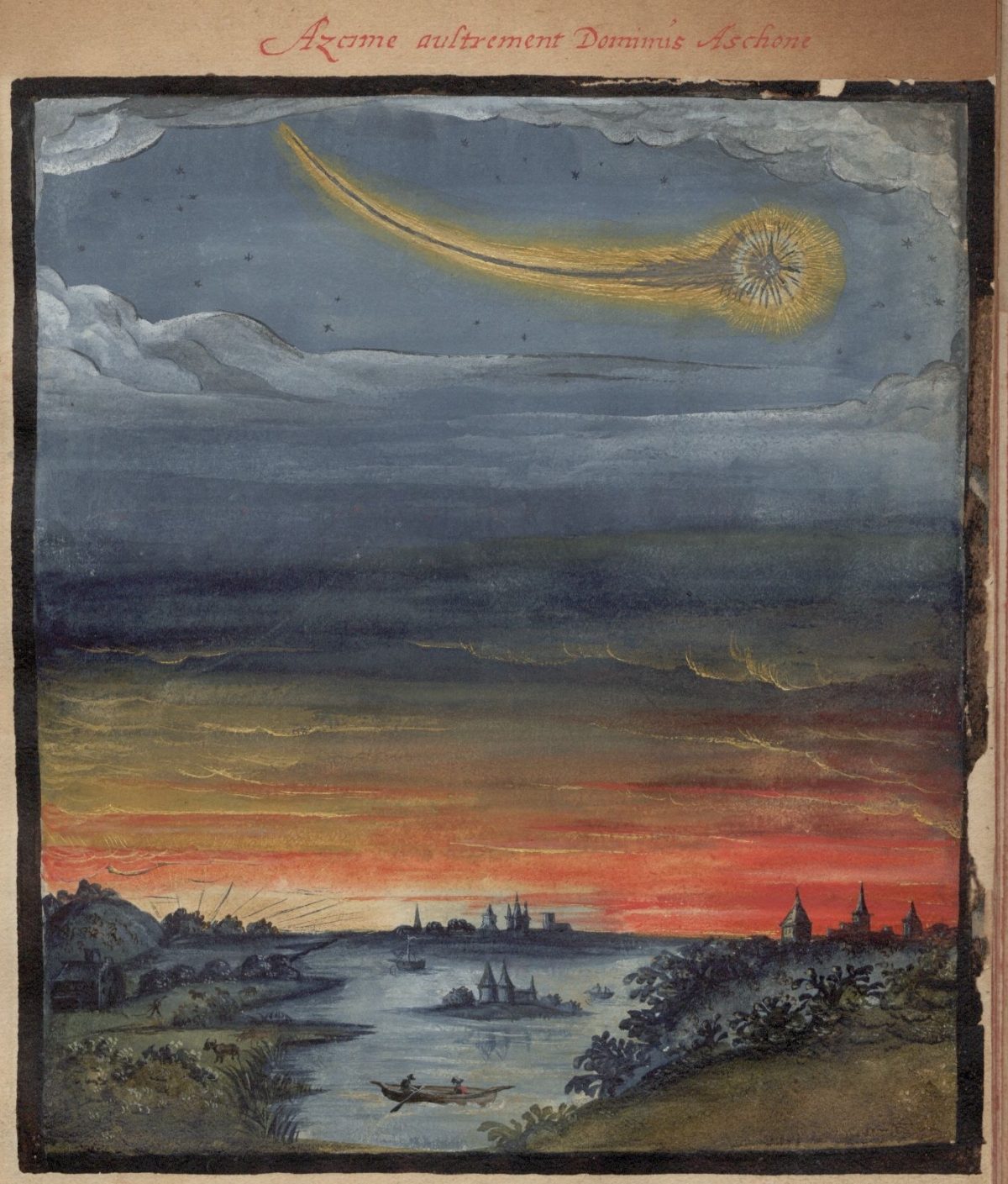

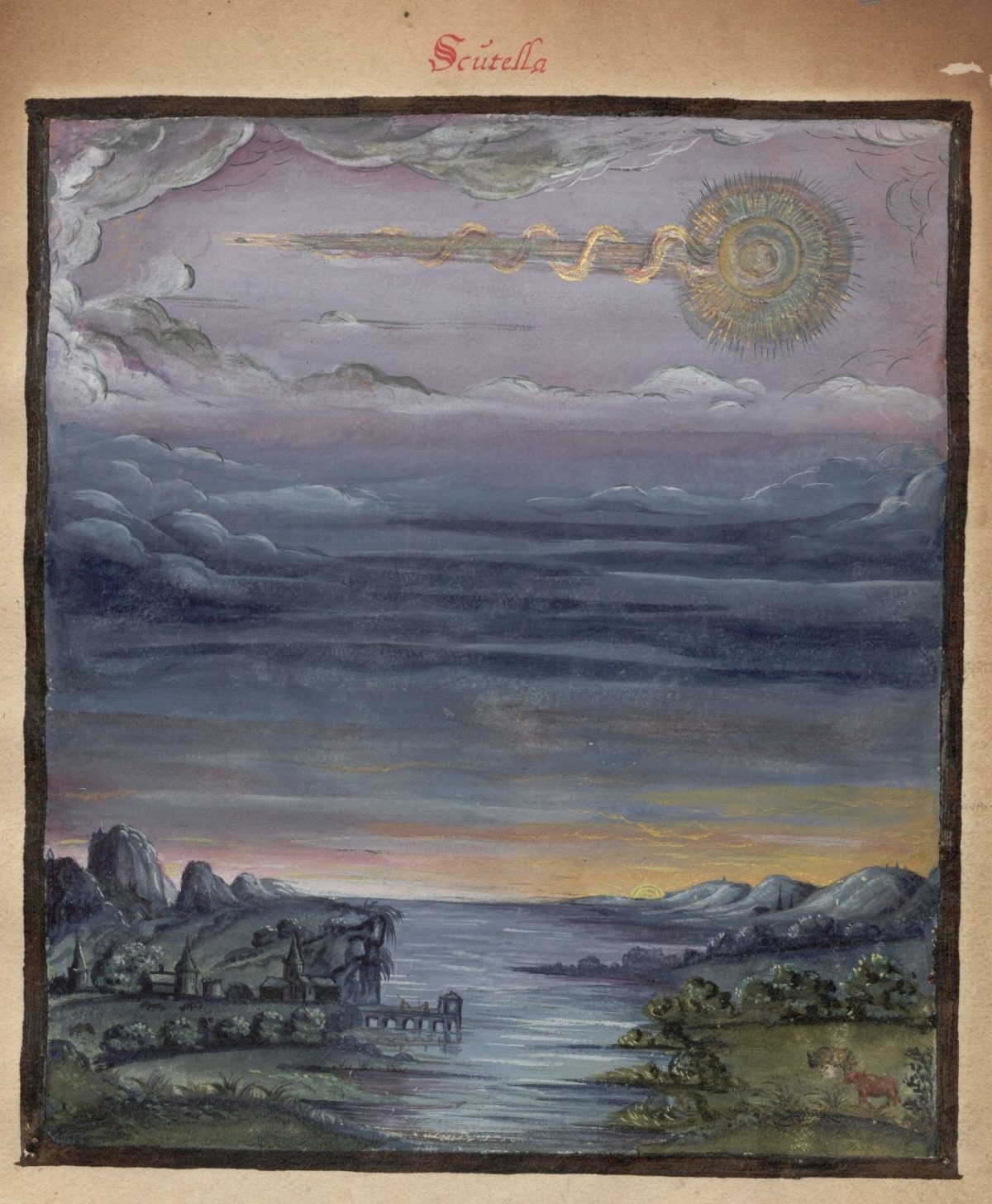

The ‘Kometenbuch’ was created in Flanders or NE France in 1587, writes Paul K. Two editions are known to exist; the other copy is owned by the Warburg Institute in London, and contains near-identical sketches, but has an extra chapter of writing. The names of the author and illustrator are unknown. The text would appear to reflect the rather outlandish, or at least exaggerated, qualities we see in the painted miniatures. In other words, the text purports to compile a history of comet science from ancient times up to the late Medieval period, but it does so in such a way that the emphasis is on ‘popularising’ the content. Early Modern pop-science, if you will. So what began as factual depictions of celestial phenomena, morphed into spectacular genre paintings.

The writing isn’t so distorted that it masks the true origins, however. Our author incorrectly (or pretentiously) names Ptolemy as a source – but the papers cited in ‘Kometenbuch’ contain no reference to comets at all. Instead, it has been determined that the true source for the manuscript contents lies with an anonymous Spanish book, ‘Liber de Significatione Cometarum’, published in 1238. The 13th century book contained astrological and astronomical information and observations from ancient history and was translated into many languages; one edition in simplified French from the 15th century likely provided the ‘Kometenbuch’ author’s foundation material.

The painting scenes tend to follow from the descriptions in the text; for instance, comet Aurora was said to trigger wars, fire, strong winds and the like, which is why the corresponding image depicts burning houses, fleeing people etc. The Miles comet is described as being “as big as a horse” and the harbinger of upheaval to laws, social norms and hard times for royalty: cryptically sketched as a man defecating beneath a sky filled by a giant-tailed comet (the tails were said to carry the ‘effects’ from the heavens), while a perplexed owl looks on from a tree.

Throughout history, the appearance of these beautiful and colourful comets has been regarded as significant events. In general, people held superstitious beliefs about comets and were convinced that they were bad omens and associated with the forces of dark magic or a sign of punishment to come from displeased Gods. Comets ‘announced’ that war, famine, pestilence and other consequences of sinful behaviour were on their way. This kind of religious punishment explanation of comets persisted up until the 16th and 17th centuries in Europe, when the speculative literature (and illustrations!) gave way, over time, to a more scientific appreciation of the phenomena.

Miles

Gebea ou Tenaculum (Luna) aus der Zeit Kaiser Neros

“The ancient Egyptians and Chaldeans [..] by a long Courſe of Obſervations, were able to predict the Apparitions of Comets. But ſince they are alſo ſaid, by Help of the ſame Arts, to have progoſticated Earthquakes and Tempeſts, ’tis paſt all Doubt, that their Knowledge in theſe Matters, was the Reſult rather of meer Aſtrological Calculation, than of any Aſtronomical Theories of the Cœleſtial Motions.

And the Greeks, who were Conquerors of both thoſe People, ſcarce found any other ſort of Learning amongſt them, than this. So that ’tis the Greeks themſelves as the Inventors (and eſpecially to the Great Hipparhchus) that we owe this Aſtronomy, which is now improv’d to Such a Heighth.

But yet, amongſt theſe, the Opinion of Ariſtotle (who wou’d have Comets to be nothing elſe, but ſublunary Vapours, or Airy Meteors) prevail’d So far, that this moſt difficult part of the Aſtronomical ſcience lay altogether neglected; for no Body thought it worth while to take Notice of, or write about, the Wandring uncertain Motions of what they eſteemed Vapours floating in the Æther; whence it came to paſs, that nothing certain, concerning the Motions of the Comets, can be found tranſmitted from them to us.

But Seneca the Philoſopher, having conſider’d the Phenomena of Two remarkable Comets of his Time, made no ſcruple to place them amongſt the Cœleſtial Bodies; believing them to be ſtars of equal Duration with the World, tho’ he owns their Motions to be govern’d by Laws not as then known or found out. And at laſt (which was no untrue or vain Prediction) he foretells, that there ſhould be Ages ſometime hereafter, to whom Time and Diligence ſhou’d unfold all theſe Myſteries, and who ſhou’d wonder that the Ancients cou’d be ignorant of them, after ſome lucky Interpreter of Nature had ſhewn, in what Parts of the Heavens the Comets wander’d, what, and how great they were. Yet almoſt all the Aſtronomers differ’d from this Opinion of Seneca; neither did Seneca himſelf think fit to ſet down thoſe Phænomena of Motion, by which he was enabled to maintain his Opinion; Nor the Times of thoſe Appearances, which might be of uſe to Poſterity, in order to the Determining theſe Things.

And indeed, upon the Turning over very many Hiſtories of Comets, I find nothing at all that can be of ſervice in this Affair, before, A.D. 1337. at which time Nicephorus Gregorus, a Conſtantinopolitan Hiſtorian and Aſtronomer did pretty accurately deſcribe the Path of a Comet amongſt the Fix’d Stars, but was too laxe as to the Account of the Time; ſo that this moſt doubtful and uncertain Comet, only deſerves to be inſerted in our Catalogue, for the ſake of its appearing near 400 years ago.”

– A Synopsis of the Astronomy of Comets’ , Miscellanea Curiosa: Containing a Collection of Some of the Principal Phænomena in Nature, Accounted for by the Greatest Philosophers of this Age..’ Edited by Edmund Halley, 1708. Amazon

Etoiles courants

Aczime aultrement Dominis Aschone (Merkur)

Aurora oder Matuta (Feuer)

Argentum im Zeichen des Jupiters

Veru, ein Komet aus dem Jahre 69 n. Chr.

Pertica orientalis und occidentalis

Scutella

Rosa

Via:

- ‘Kometenbuch’ 1587, is available online from Universitätsbibliothek Kassel in Germany.

- The majority of writing above is paraphrased from a translated manuscript commentary/bibligraphy book^: ‘Kasseler Handschriftenschätze’ c. 1985 by Hartmut Broszinski.

- I am, for the manyeth time, deeply grateful for the translational assistance provided by typographer-extraordinaire, Nina Stössinger (@ninastoessinger). THANKS NINA!! Nina is studying again now, so if there’s anybody out there who is very fluent in BOTH English AND German, and who wouldn’t mind giving me some occasional translational assistance, please get in contact: gmail/peacay or @BibliOdyssey.

- Thanks also to Harvard Library’s John Overholt.

- Previously: The Comet Book (includes more background links) and, in general: astronomy & astrology.

- Addit: never let it be said that I d/won’t allow criticism to appear here (however factually incorrect it may be – they regard the details of the write-up here – with which they disagree – the fault of ‘the blogger’. Perhaps they ought to read all these bullet points. My opinion doesn’t really surface. A lot of work and a few people were responsible for producing this commentary which, as noted, is essentially a summarised translation.)

- This post first appeared on the BibliOdyssey website.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.