Fascist, and they attack,

Nobody worry about that,

Fascist, and they attack,

We will fight them back.

– Lynton Kwesi Johnson, Fight Dem Back

On Saturday 13 August 1977, the self-declared ‘Paki bashers’, ‘black beaters’ and ‘Yid haters’ were ready to march through south-east London. Around 500 members of the far-Right National Front were marching for ‘law and order’. Five hundred is not that many. The far-Right in the UK has never reached the heights of their cohorts in Germany, Italy or Spain, where the fascists held the power and the guns. But they marched in hope that locals would turn out in support.

“The dialogue which gets overlooked, because it is less palatable, is that there was considerable support for the NF,” says John Price, head of history at Goldsmiths University, which stands close to where clashes took place. A local council by-election in Deptford saw the far-Right secure almost half the vote. Together the National Front and its breakaway faction, the National party, secured 44.5%, a total not quite enough to beat Labour but sufficient to relegate the Conservatives into fourth place, says the Guardian. The Labour winner in the safe Labour seat polled just 1% more than the two anti-immigration parties combined.

NF Spokesman Richard Edmonds said by demonstrating in a march from New Cross to Lewisham they were “standing up for white people”. They were highlighting what they considered to be the disproportionate amount of street crime committed in the area by black youths.

But surely crime numbers deal in facts and evidence not hunches and bias? Racism was rife. To be black was to be a criminal in waiting. In April 1978, the anti-racism Runnymede Trust launched a report into the Sus Law, Section 4 of the Vagrancy Act that made it an offence to be a “suspected person loitering with intent to commit a felonious offence”. The use of ‘sus’ created discontent amongst black and minority ethnic communities who felt that it was used by police to target young black people. The report concluded:

That in the interests of police and community relations, this was a counter-productive method of crime prevention, and that its extensive use in parts of London and one or two other major towns has merely succeeded in convincing young black people and their parents of the racial prejudice of the British police force and the inherent unfairness of the British legal system; and that other charges such as attempted theft could be used to arrest the intending thief.

Sus made it a crime to be standing still, walking or looking whilst black. Being black made you as suspect. Being black made you a target of police brutality.

Police were targeting blacks. They’d targeted blacks for years. Examples are too numerous to mention here. So let’s pick one nasty incident of many. On 24 September 1973, five plain-clothes detectives raided a house in Nigel Road, Peckham, south-east London. They found one cannabis plant in the back garden. The ground floor tenant admitted the weed was his. The five young and healthy policemen marched upstairs, where Michael Thomas and Jessie Antoine lived, a couple described as “elderly” and in fragile health. The police said a violent struggled ensued in which Mr Thomas dragged at least three of the officers the length of the landing. The frail man then broke free, bit one of the coppers on the hand and stabbed another with some scissors. The five, poor defenceless policemen found no drugs at the address. But not for want of trying. They turned the home inside out. The coppers then called for uniformed support. The couple were arrested and taken to the police station. Jessie Antoine had no coat or shoes. They were locked up for 10 days and charged with assaulting the five officers. In December 1973, an Old Bailey judge instructed the jury to find the couple not guilty. According to the defence barrister’s note: “The jury could have been left in little doubt that the judge was deeply concerned about the evidence and indicated that not guilty verdicts should be returned. The reasons for this must have been basically – the patent honesty of the two defendants, the substantial discrepancies in the prosecution evidence, the unlikelihood of the allegations made, and the medical evidence.” The couple took action against the police, who settled out of court.

We could on. And on. And on. But if there was one dose of police bigotry that led to Battle of Lewisham, it was this. In a series of dawn raids on 30 May 1977, police arrested 21 young black people in connection with muggings in south-east London. Police said that they believed the “gang” were responsible “for 90 per cent of the street crime in south London over the past six months”. The accused stood in the dock at Camberwell Green Magistrates’ Court on 1 June 1977. Some of the accused fought with the police while people in the public gallery tried to invade the court.

In response to the heavy-handed arrests, the Lewisham 21 Defence Committee was set up. On 2 July 1977, the Committee held a demonstration in New Cross which was attacked by members of the National Front who threw rotten fruit and bags of caustic soda.

Jim start to wriggle

De police start to giggleMama, mek I tell you wa dem do to Jim?

Mek I tell you wa dem do to him?Dem thump him in him belly and it turn to jelly

Dem lick him ‘pon him back and him rib get pop

Dem thump him ‘pon him head but it tough like lead

Dem kick him in him seed and it started to bleedMama, I jus couldn’t stan’ up deh, nah do nuttin’

– Lynton Kewish Johnson, Sonny’s Lettah (Anti-sus poem)

“We were not a rabble, just a group of Caribbean blacks who had been building communities of which we were justly proud,” recalled Darkus Howe in 2007. “I knew the local turf well. I had been married a few years earlier at the Anglican church in Wickham Road, off Lewisham Way. My daughter (the first of my brood) saw the light of day at Lewisham Hospital. Our small community had developed a kinship. Perhaps not as strong as Brixton, but tight enough.”

Buoyed by racist police brutality and positive election results, the National Front announced plans for a march from New Cross to Lewisham. NF organiser Martin Webster told the press: “We believe that the multi-racial society is wrong, is evil and we want to destroy it.” Its aims were totalitarian. Its method was to foment hatred. Local church leaders, Lewisham Council and the Liberal Party all called for the march to be banned, but Metropolitan Police Commissioner David McNee declined to make an application to the Home Secretary for a ban to be imposed. McNee reasoned that if a ban were imposed, then this would lead to “increasing pressure” to ban similar events and would be “abdicating his responsibility in the face of groups who threaten to achieve their ends by violent means.” McNee later admitted the NF march was “deliberately provocative”.

In response to the NF march scheduled for the afternoon, anti-fascists mustered by the All Lewisham Campaign against Racism and Fascism (Alcaraf) held their own earlier protest. By the time the NF were ready to go, around 4,000 anti-fascists were in the area. And then the obvious happened. Things kicked off.

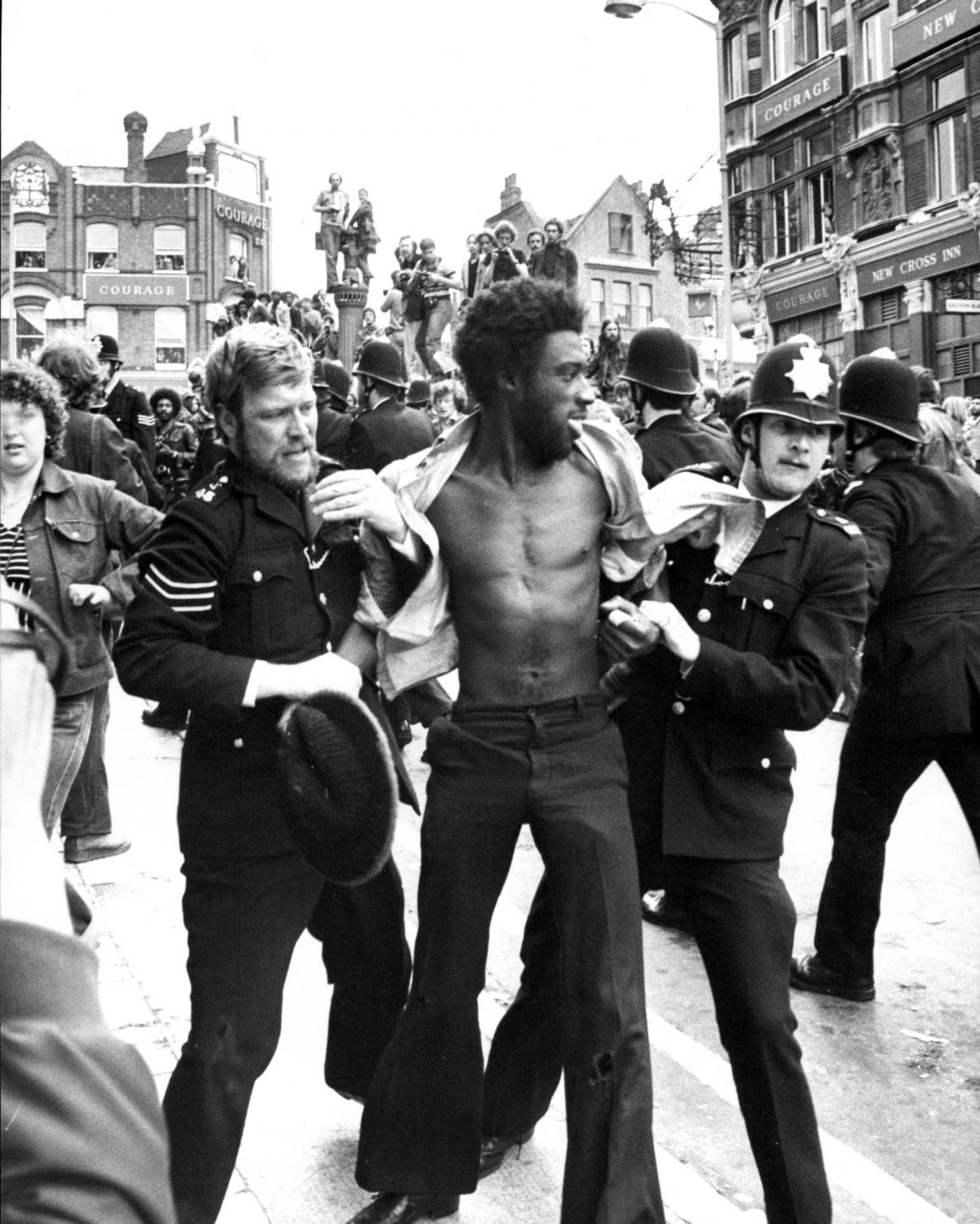

The Observer reported, “violence threatened to spill over when a crowd of about 200 Millwall football fans arrived shouting “Up the National Front, kill the blacks”’. But the NF was outnumbered. Around 3,000 police held the crowds back. Unable to get to the far-Right, protestors attacked the people many saw as as their enablers: the police. One policeman was knocked unconscious. Two more were dragged from their horses. Eleven police were hospitalised. Police used dustbin lids to protect themselves and the NF from the hail of bottles, bricks, marbles, faeces and amonia. The better equipped police had riot shields – the first time such equipment has been used in the UK outside Northern Ireland.

Police petled with missiles by people angry at the N.F. march

RIOTS SPARKED BY A NATIONAL FRONT MARCH, LEWISHAM, LONDON, BRITAIN – 1977

Lewisham Anti-National Front March. Police Clash With Demonstrators In Front Of Journalist With Tape Recorder

Lewisham National Front March. Police Clash With Demonstrators In Front Of Journalist With Tape Recorder

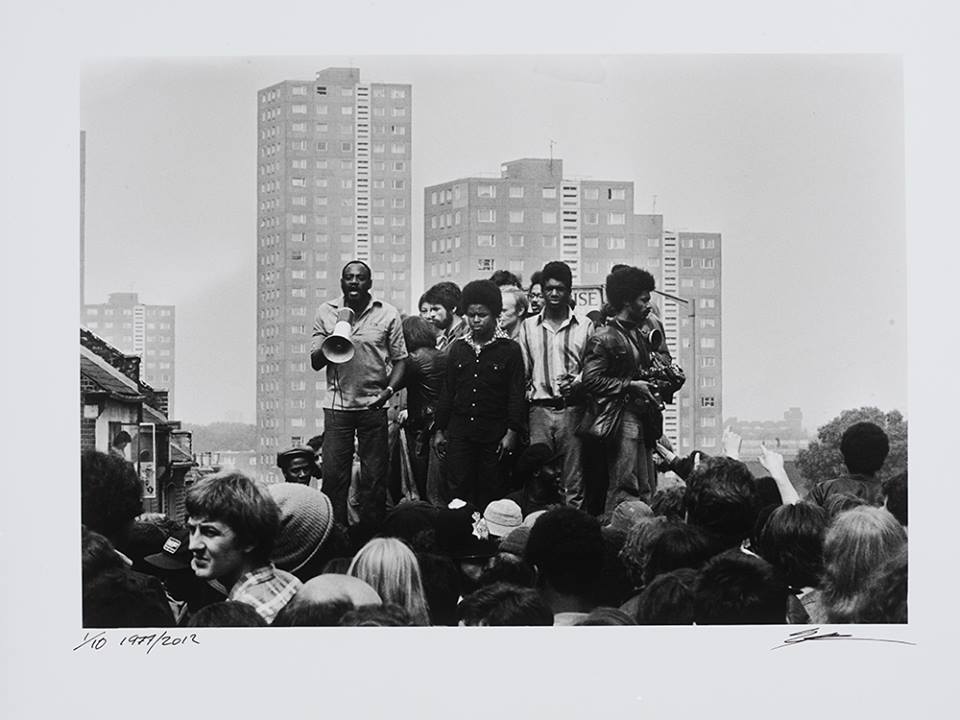

Darcus Howe was there:

A puny group of reactionaries and fascists under the banner of the National Front took the decision to mobilise the white working classes by marching boldly through the black community. Their confidence stemmed from a myth that black and Asian people were docile, if not imbecilic… They had the police at their side: a militarised section of the Metropolitan Police that had built a reputation as vicious, baton-wielding thugs. Nothing in the press had prepared the National Front and police for the ferocity of the ambush they encountered outside Goldsmiths College. Our reaction was spontaneous. The crowd, black and white, pounced on this vanguard of racism and inflicted on those reactionaries a merciless hiding. And how they ran away!

Flags were abandoned. NF members and their supporters scampered, tails tucked between their legs. They screamed and hollered…

Darcus Howe addressing the crowd at the Anti- National Front Demonstration, Lewisham, South London, 1977

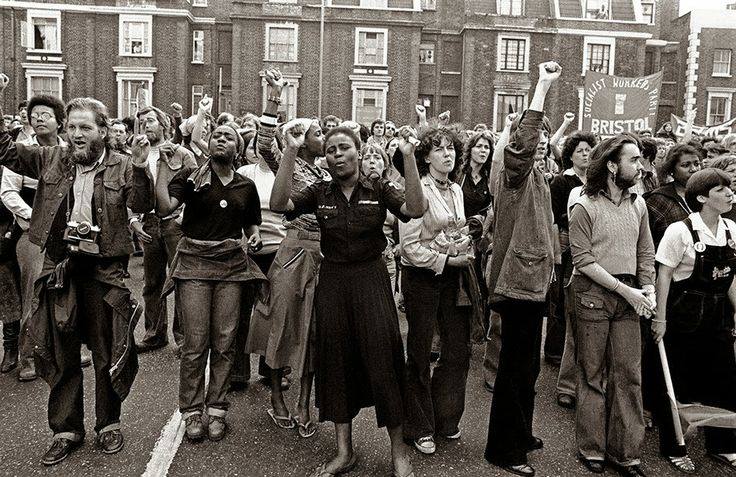

Anti- National Front Demonstration, Lewisham, South London, 1977

Outside the rebels were freezin’ cold

Babylonian tyrants descended

Bounced on the brothers who were bold

So with a flick of the wris’, a jab and a stab

The song of hate was sounded

The pile of oppression was vomited

And two policemen wounded

Righteous, righteous war

– Linton Kwesi Johnson, Five Nights of Bleeding

Lewisham : Anti- National Front Demonstration, 1977

In 2018, footage was found showing the scene. We hear testimony from eyewitnesses – often contradicting official reports. The film was shot by volunteers connected to the Albany Video project in Deptford.

Linton Kwesi Johnson was born in 1952 in Chapelton, Jamaica. He moved to London in 1963 to be with his mother and went on to read Sociology at Goldsmiths College, University of London.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.