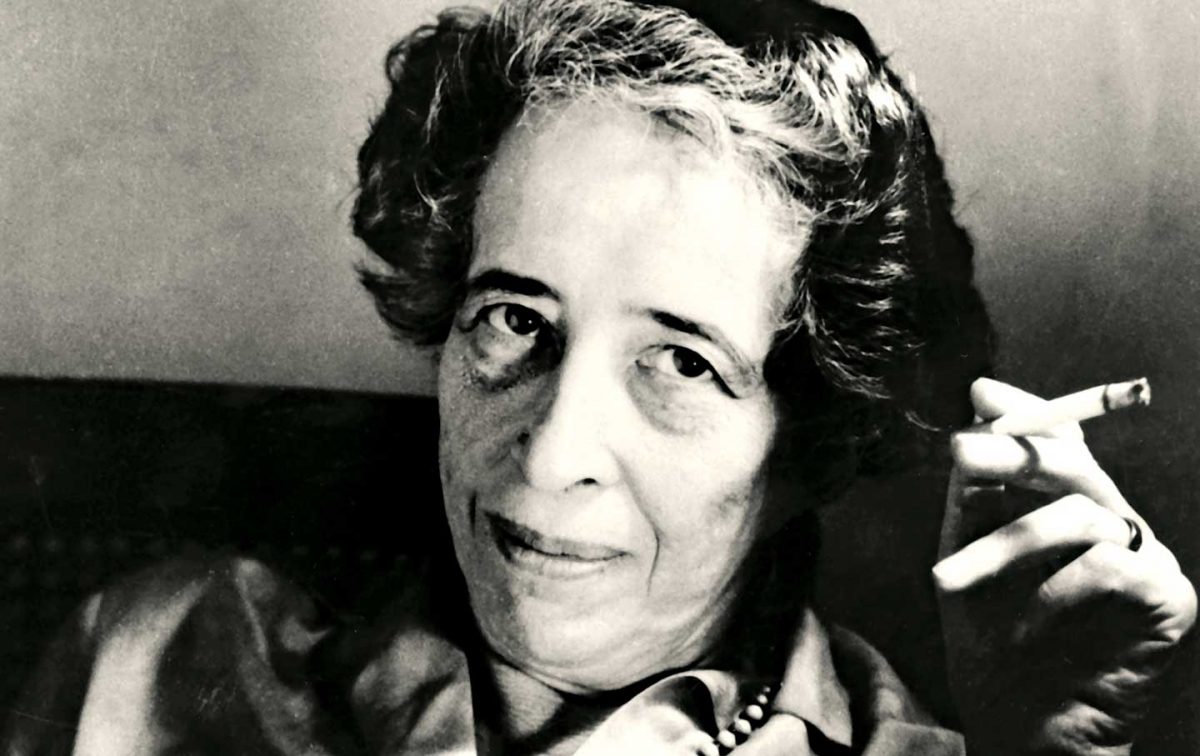

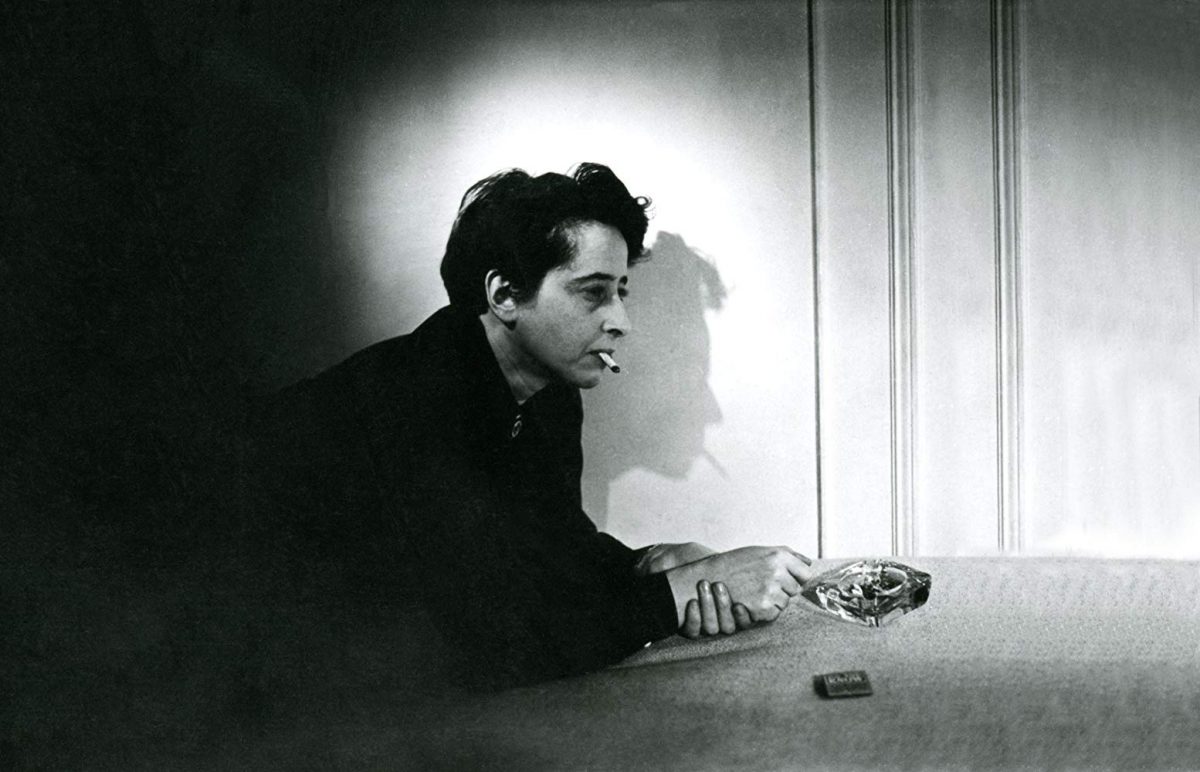

Hannah Arendt (October 14, 1906–December 4, 1975) understood that evil does not announce itself with fanfare and a jet of sulphur. Evil creeps. In 1961, The New Yorker commissioned Arendt to report on the trail of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem. This German-born “illegal emigrant” who’d fled the Nazis after they’d arrested her in 1933 and through wit and foresight escaped the Gurs internment camp and transportation to Auschwitz-Birkenau, reaching the US in 1941, was now appraising the face of evil in her spiritual homeland. She’d taken the job in the realisation this was her last opportunity to see a major Nazi “in the flesh”.

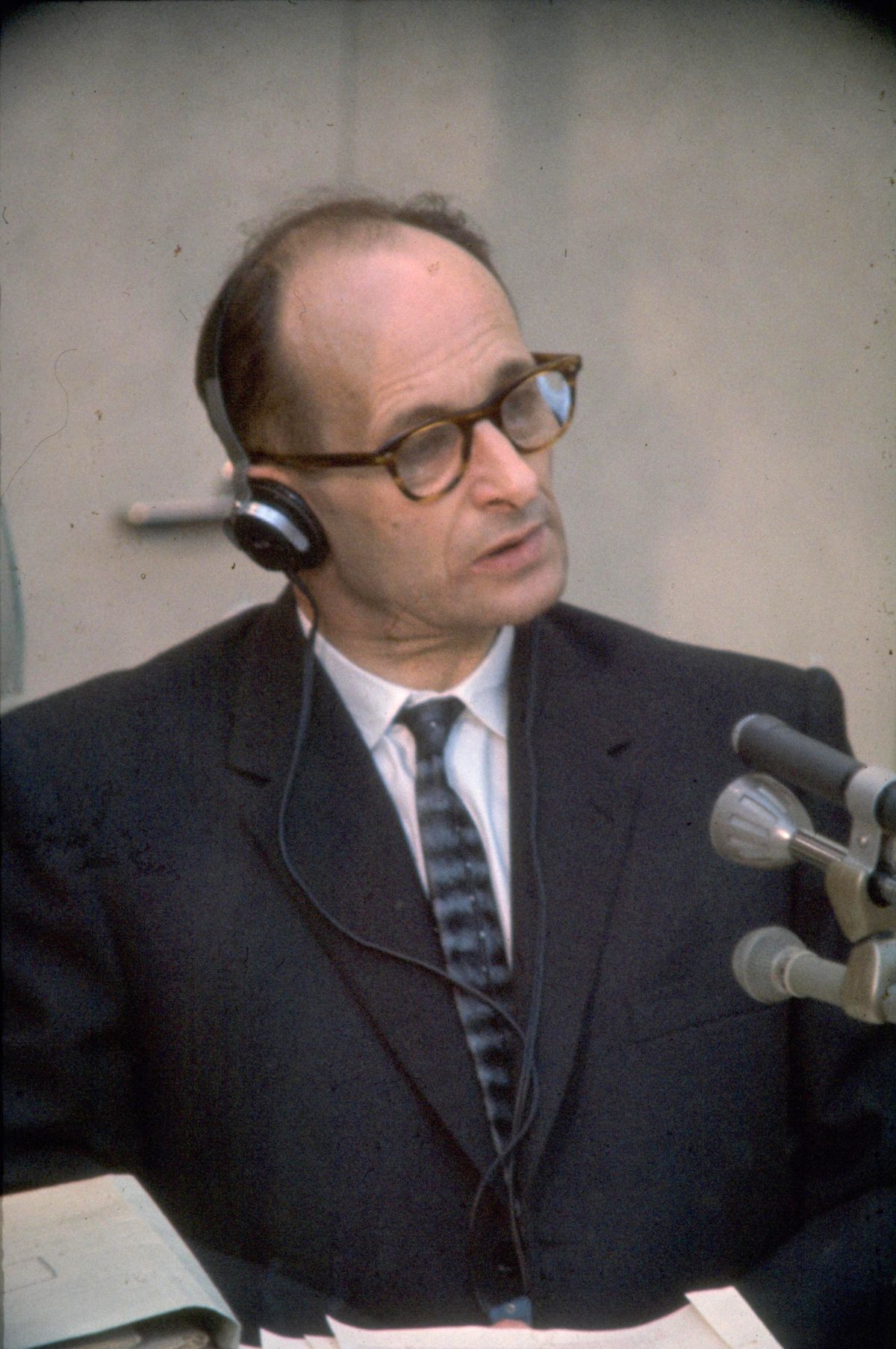

Who was this man who had murdered so many and ordered many more to kill many more? Was he special, marked in some way for evil? Was evil really so humdrum, the sink of degraded humanity wrapped in the form of a little grey man, this mentally negligible, boastful, vain bureaucrat who’d overseen the trains that took millions of people to their deaths? Here before the world, sat in a glass box in a Jerusalem court ready to be tried by the people whose existence he had sought to rub out was the manifestation of “the dilemma between the unspeakable horror of the deeds and the undeniable ludicrousness of the man who perpetrated them”. He was “terribly and terrifyingly normal”. For Arendt, Eichmann epitomised the “banality of evil”.

Adolf Eichmann at his trial

Not that banal is the same as the everyday. As Maria Popova notes: “Among those who misunderstood her notion of the ‘banality’ of evil to mean a trivialization of the outcome of evil rather than an insight into the commonplace motives of its perpetrators was the scholar Gerhard Scholem, with whom Arendt had corresponded warmly for decades. At the end of a six-page letter to Scholem from early December of 1964, she crystallizes her point and dispels all grounds for confusion with the elegant precision of her rhetoric”:

You are quite right, I changed my mind and do no longer speak of “radical evil.” … It is indeed my opinion now that evil is never “radical,” that it is only extreme, and that it possesses neither depth nor any demonic dimension. It can overgrow and lay waste the whole world precisely because it spreads like a fungus on the surface. It is “thought-defying,” as I said, because thought tries to reach some depth, to go to the roots, and the moment it concerns itself with evil, it is frustrated because there is nothing. That is its “banality.” Only the good has depth that can be radical.

As hymned writer Maya Angelou put it in a 1982 conversation with American journalist Bill Moyers:

“Throughout our nervous history, we have constructed pyramidic towers of evil, ofttimes in the name of good. Our greed, fear and lasciviousness have enabled us to murder our poets, who are ourselves, to castigate our priests, who are ourselves. The lists of our subversions of the good stretch from before recorded history to this moment. We drop our eyes at the mention of the bloody, torturous Inquisition. Our shoulders sag at the thoughts of African slaves lying spoon-fashion in the filthy hatches of slave-ships, and the subsequent auction blocks upon which were built great fortunes in our country. We turn our heads in bitter shame at the remembrance of Dachau and the other gas ovens, where millions of ourselves were murdered by millions of ourselves. As soon as we are reminded of our actions, more often than not we spend incredible energy trying to forget what we’ve just been reminded of.”

Eichmann was not good. He was not merely obeying orders. He carried out his work with conviction and pride. Arendt knew that. But she also found space to consider this idea of the individual lost in the machine, notably in her 1951 work The Origins of Totalitarianism:

“Just as terror, even in its pre-total, merely tyrannical form ruins all relationships between men, so the self-compulsion of ideological thinking ruins all relationships with reality. The preparation has succeeded when people have lost contact with their fellow men as well as the reality around them; for together with these contacts, men lose the capacity of both experience and thought. The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exist.”

Hannah Areednt’s grave at Bard College Cemetery

Annandale-on-Hudson, Dutchess County, New York, USA

What was Eichmann’s reality? He was a serial member of institutions – The Young Men’s Christian Association; the Wandervogel; the Jungfrontkämpferverband; the Schlaraffia; the SS. “Wherever the crowd goes run in the other direction. They’re always wrong,” wrote Charles Bukowski. In The True Believer, Eric Hoffer wrote of this need to be part of the crowd:

“Those who see their lives as spoiled and wasted crave equality and fraternity more than they do freedom. If they clamor for freedom, it is but freedom to establish equality and uniformity. The passion for equality is partly a passion for anonymity: to be one thread of the many which make up a tunic; one thread not distinguishable from the others. No one can then point us out, measure us against others and expose our inferiority.

“To ripen a person for self-sacrifice he must be stripped of his individual identity and distinctness. He must cease to be George, Hans, Ivan or Tadao- a human atom with an existence bounded by birth and death. The most drastic way to achieve this end is by complete assimilation of the individual into a collective body. The fully assimilated individual does not see himself and others as human beings. When asked who he is, his automatic response is that he is a German, a Russian, a Japanese, a Christian, a Moslem, a member of a certain tribe or family. He has no purpose, worth and destiny apart from his collective body; and as long as that body lives he cannot really die.”

Faced with the end of the Thousand Year Reich, Eichmann mused: “I sensed I would have to live a leaderless and difficult individual life, I would receive no directives from anybody, no orders and commands would any longer be issued to me, no pertinent ordinances would be there to consult – in brief, a life never known before lay ahead of me.”

And so back to 1963. Arendt’s report was published in the book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. And parts of it bring a chill of truth today as they did then. In the UK and Europe, anti-Semitism is on the rise.

It never went away. As Arendt wrote:

Thanks to Hitler, anti-Semitism has been discredited, perhaps not forever but certainly for the time being, and this is not because the Jews have become more popular all of a sudden but because not only Ben-Gurion but most people have “realized that in our day the gas chamber and the soap factory are what anti-Semitism may lead to.”

So how can Eichmann rise to such power that so many people’s lives (and deaths) were in his hands, this eldest of five children born to an accountant and his hausfrau, a man who wasn’t bright enough to finish high school, or even to graduate from a vocational school for engineering, who nonetheless held papers on which ‘construction engineer’ was given as his profession? How did it happen? Arendt pictured Eichmann as a clown:

What he said was always the same, expressed in the same words. The longer one listened to him, the more obvious it became that his inability to speak was closely connected with an inability to think, namely, to think from the standpoint of somebody else. No communication was possible with him, not because he lied but because he was surrounded by the most reliable of all safeguards against the words and the presence of others, and hence against reality as such.

But not to worry because Xi Jinping, Jeremy Corbyn, Donald Trump et al are idealists – and idealists are the kind of people you can believe in because their ideals are all they have and all they are. If you’re looking for validation, you can borrow them and have these ideals define you, too:

An “idealist,” according to Eichmann’s notions, was not simply a man who believed in an “idea” or a man who did not steal or accept bribes, though these qualifications were indispensable. An “idealist” was a man who lived for his idea (hence he could not be a businessman, for example) and who was prepared to sacrifice for his idea everything and, especially, everybody. When he asserted during the police examination that he would have sent his own father to his death if that had been required, he did not mean merely to stress the extent to which he was under orders, and ready to obey them; he also meant to show what an “idealist” he had always been. Of course, the perfect “idealist,” like everybody else, had his personal feelings, but if they came into conflict with his “ideal,” he would never permit them to interfere with his actions.

But there is hope. In a letter to the novelist Mary McCarthy, Arendt noted that she no longer believed in “holes of oblivion” because “there are simply too many people in the world to make oblivion possible”:

The holes of oblivion do not exist. Nothing human is that perfect, and there are simply too many people in the world to make oblivion possible. One man will always be left alive to tell the story…

The lesson of such stories is simple and within everybody’s grasp. Politically speaking, it is that under conditions of terror most people will comply but some people will not, just as the lesson of the countries to which the Final Solution was proposed is that “it could happen” in most places but it did not happen everywhere. Humanly speaking, no more is required, and no more can reasonably be asked, for this planet to remain a place fit for human habitation.

What are the lessons, then? Well, we should have faith in humanity. It always wins. And we must listen to the survivor’s story. But that’s never enough. Jeremy Kohn, director, Hannah Arendt Center, New School University, has a word to the wise:

The trouble with most accounts from recollection or by eyewitnesses is that in direct proportion to their authenticity they are unable “to communicate things that evade human understanding and human experience.” They are doomed to fail if they attempt to explain psychologically or sociologically what cannot be explained either way, that is, to explain in terms that make sense in the human world what does not make sense there, namely, the experience of “inanimate men” in an inhuman society. Moreover, survivors who have “resolutely” returned to the world of common sense tend to recall the camps as if they “had mistaken a nightmare for reality.” The “phantom world” of the camps had indeed “materialized” with all the “sensual data of reality,” but in Arendt’s judgment that fact indicates not that a terrifying dream had been experienced but that an entirely new kind of crime had been committed. One of the underlying reasons for the controversy created by Arendt’s study of Eichmann was and remains the failure of many readers, both Jews and non Jews, to make the tremendous mental effort required to transcend the fate of one’s own people and see what was pernicious for all humanity. The notion of a “crime against humanity” was introduced in the Nuremberg trials of major war criminals in 1946, but in Arendt’s opinion the crime was confused there with “crimes against peace” and “war crimes” and had never been properly defined nor its perpetrators clearly recognized. To Arendt the genocide of the Jews throughout Nazi-controlled Europe was a crime against the human status, a crime “perpetrated on the body of the Jewish people” that “violated the order of mankind . . . and an altogether different community,” the world shared in common by all peoples and the comity of all nations (see Eichmann in Jerusalem, “Epilogue” — part one and part two). Not only distance but courage are required to grasp what Arendt meant by the absolute evil of totalitarianism, to see that, in the case of the Nazis, what is attributable to “the long history of Jew-hatred and anti-Semitism” is “only the choice of victims [and] not the nature of the crime.”

Hannah Arendt’s five articles on the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann by the state of Israel appeared in The New Yorker in February and March 1963.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.