The rise of photography in the mid-late 19th-century began the move away from an oral and literary tradition towards one based on image. A photograph can describe a moment in time more viscerally than the written word. Think of that picture of Jack Ruby shooting Lee Harvey Oswald. A million words have been written about that particular scene but no written description has ever equalled the power of the one split-second image taken by Dallas Times Herald photographer Robert Jackson with his Nikon.

Technology dictates form. When cameras were big box brutes – heavy, unwieldy things that took an age to process an image -photography was best served by landscape, as little moved other than the trees under the breath of the wind. Portraits meant the sitter had to learn the exacting discipline of maintaining the same position until a picture had been taken. This led to the rise of various devices and clamps to hold the sitter in a fixed position as it could take up to three minutes for a portrait photograph to be taken.

As cameras slowly changed during the 1890s, becoming lighter, more manoeuvrable, there grew a desire among photographs to create more artistic images. pictures that rivalled painting for their impressionistic beauty. One pioneer of this trend was Heinrich Kühn, a German-born amateur photographer. Back then, most photographers were amateurs. It was an expensive hobby. Only those who could afford to pay for the technology, the processing, the darkroom, and the time necessary indulge their hobby. Sure, there were those who made a living out of it, but few (if any) came from the working class. That only happened with the rise of mass-production in the 1900s.

Kühn was the son of successful merchants. He was born in Dresden and studied medicine and science. He gave up his studies to focus on photography. He was able to do this because of an allowance he inherited from his father. He moved to Vienna and became part of the Vienna Camera Club, where he was influenced by the city’s Secession artists who believed in creating Getsumkunstwerk or a total work of art.

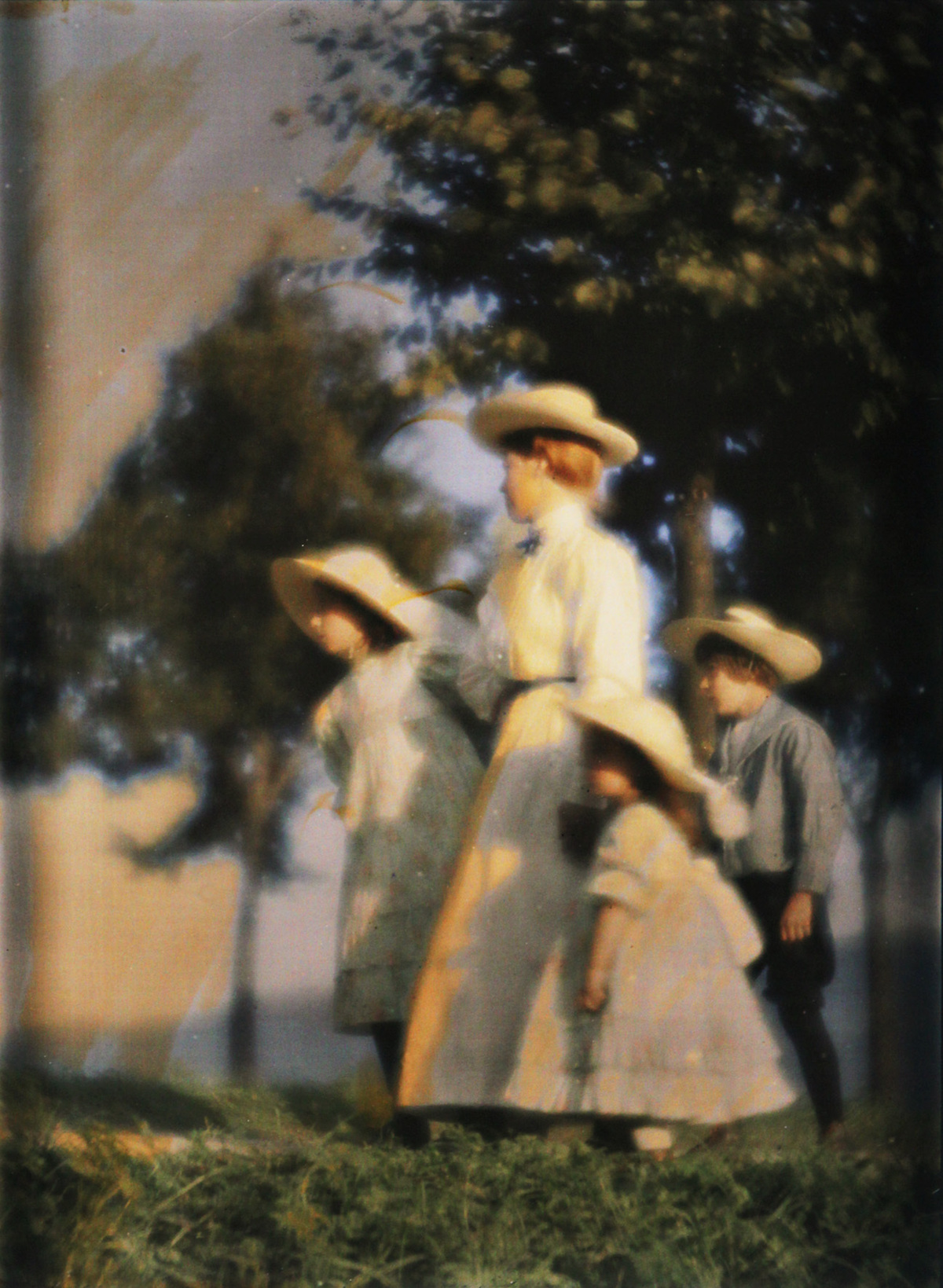

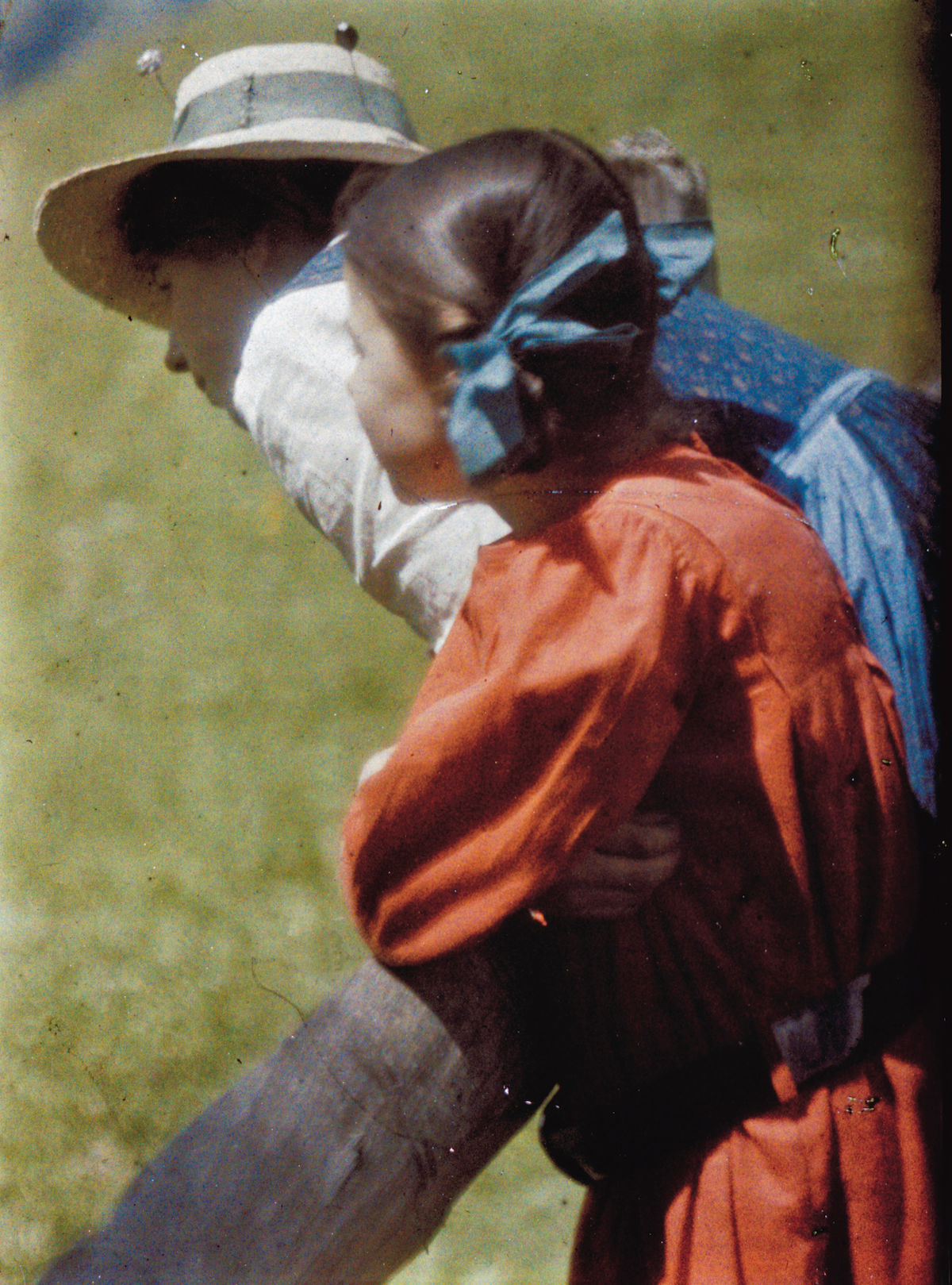

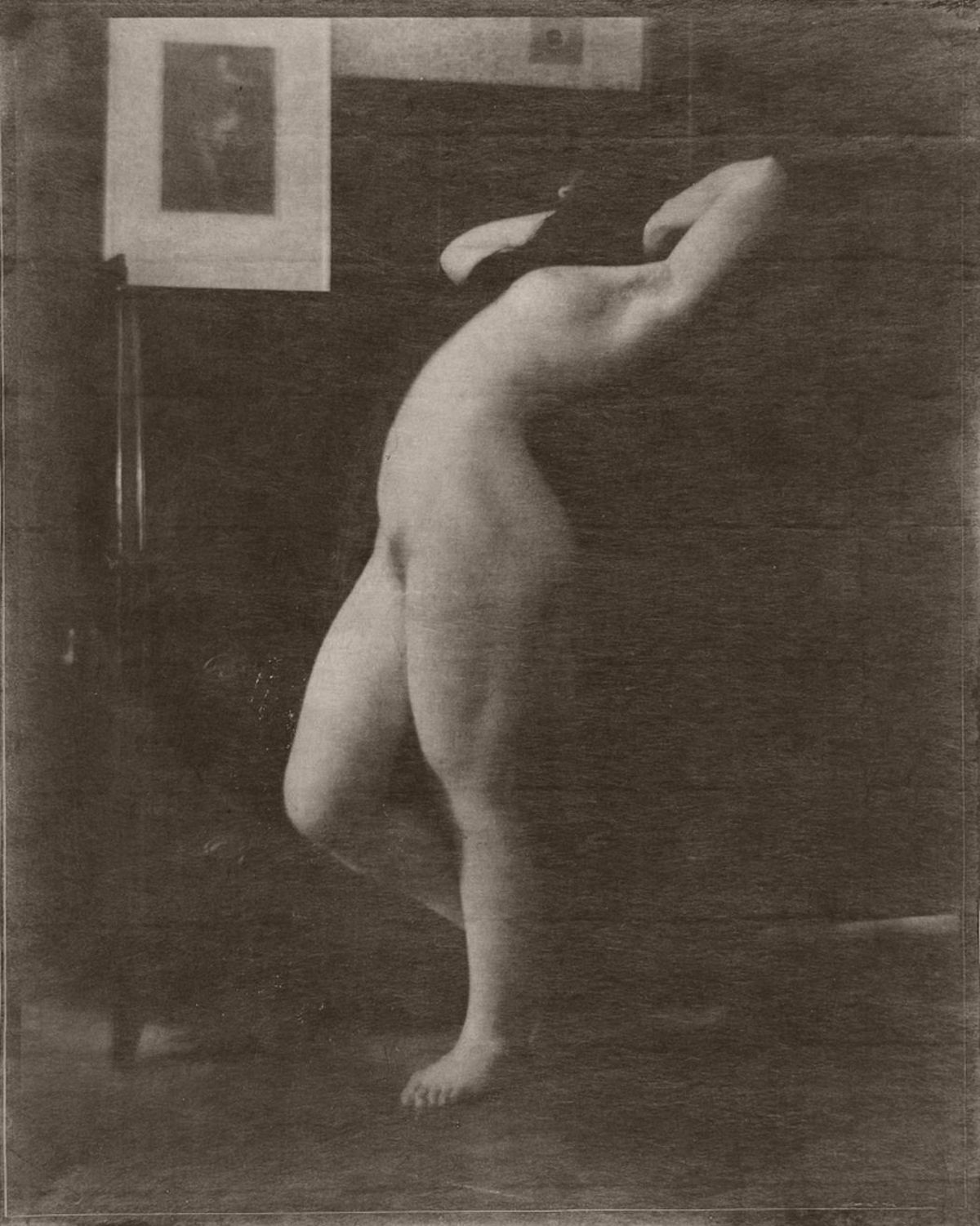

From 1890 onwards, Kühn started working on creating his “total art” photographs. His pictures were described as “painterly” and “impressionistic” but to our modern eye look more like movie stills from some great, unreleased film. Just as Robert Louis Stevenson’s concise and direct writing in say Treasure Island, which anticipated the screenplay or shooting script. Look, for example, at Stevenson’s descriptive work in the tense murderous sequence between Jim Hawkins and the coxswain Israel Hands on the rigging of the Hispaniola.

Dressed in his linen suit, Panama hat, gold-rimmed spectacles and luxuriant moustache, Kühn directed his wife and children to perform for his camera. He used gum bichromate to create his pictures. Gum bichromate was a multi-layering process first devised in 1839 which allowed the photographer to add shadow, depth, and atmosphere to a picture. The results were described as “the first artistic photographs”.

H/T WikiCommons.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.