When Derek Jarman invited his parents to the premiere of his gay sand and sandals romp Sebastiane in 1976, his father, an ex-RAF officer, remarked the film reminded him of life in the Middle East before World War II. One can only imagine… Yet, the inspiration for Jarman’s movie came from another institution of masculine life the all-boy public school.

Jarman’s father was a New Zealander who returned to the Home Country to become an Englishman. No matter how hard he tried, he was never quite accepted, too long in the Colonies. Jarman senior was always an outsider. Something his son also felt because of his homosexuality. Jarman felt he never fitted into the norm of a heterosexual society. He defined himself as an outsider at odds with the hetero world and modernity. Instead he linked himself to a mythical gay past of Alexander the Great, Caravaggio, and boyhood fantasies of clinging tightly a young olive-skinned teenager as they cycled through a holiday village in Italy.

Sebastiane grew out a script Jarman worked on with a friend Patrik Steede sometime around 1973. This script was abandoned when Steede moved to Italy to rewrite it before returning to New York. Then one day, Jarman met a young film producer called James Whaley who spoke about making a movie perhaps on St. Sebastian or maybe Shakespeare’s The Tempest? Jarman thought it an idle chat over lunch but Whaley was serious.

Jarman wanted to make movies – hence is foray into scriptwriting with Steede – but he had no idea how to go about it. He had made his own short Super-8 films and screened them to friends. He had worked as a set designer on Ken Russell‘s films The Devils and Savage Messiah, an experience that encouraged Jarman to become a film director. But none of this helped Jarman on to the next level of directing a feature film. Things changed when Russell asked if Jarman would set design Tommy, Jarman refused believing a return to set designing would destroy any chance of ever making a movie. Little did he know his chat with Whaley was about to deliver his very own first feature film.

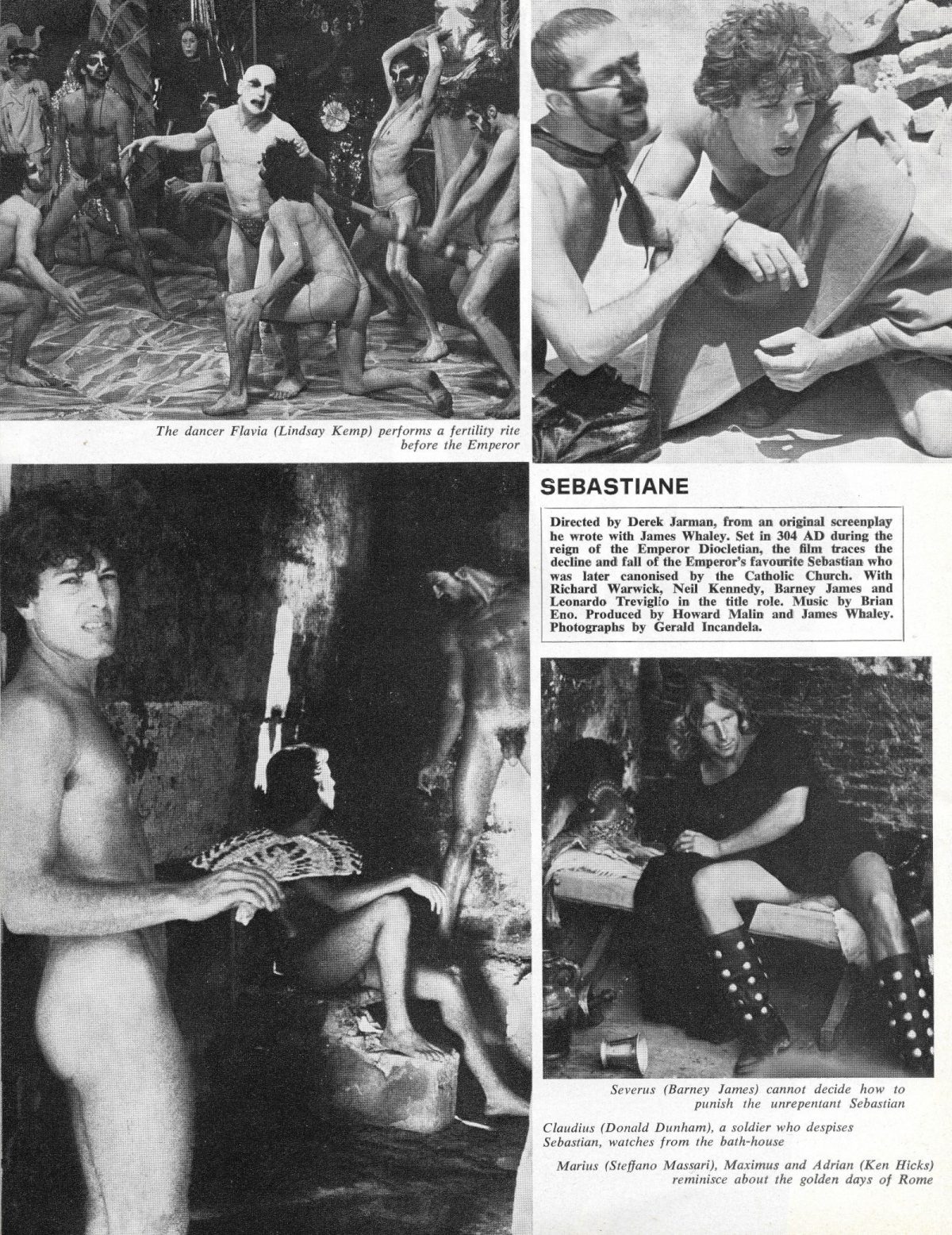

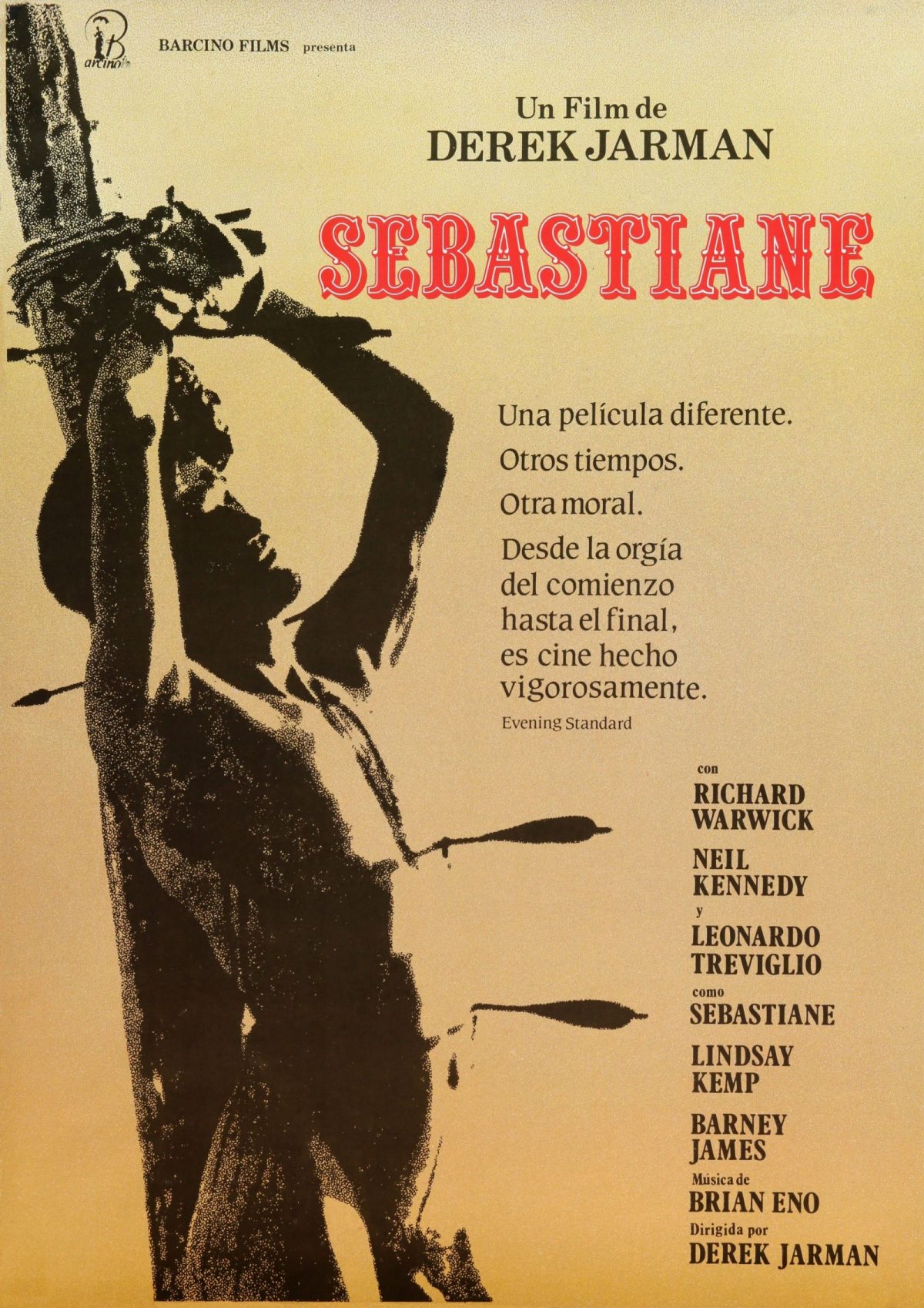

A few weeks after their meeting, Whaley returned and told Jarman he had raised most of the money to produce a film. Jarman quickly seized the opportunity. Plans were made to make a movie about Saint Sebastian. Jarman began work developing the script he had worked on with Steede. Originally written in English, Jarman and Whaley decided to have the whole script translated into pidgin Latin – which caused some consternation to the cast. Most of the dialogue was a straightforward translation but there were some jokes like the use of “Oedipus” for “motherfucker”.

‘Saint Sebastian’ by Antonella da Messina, ca. 1478.

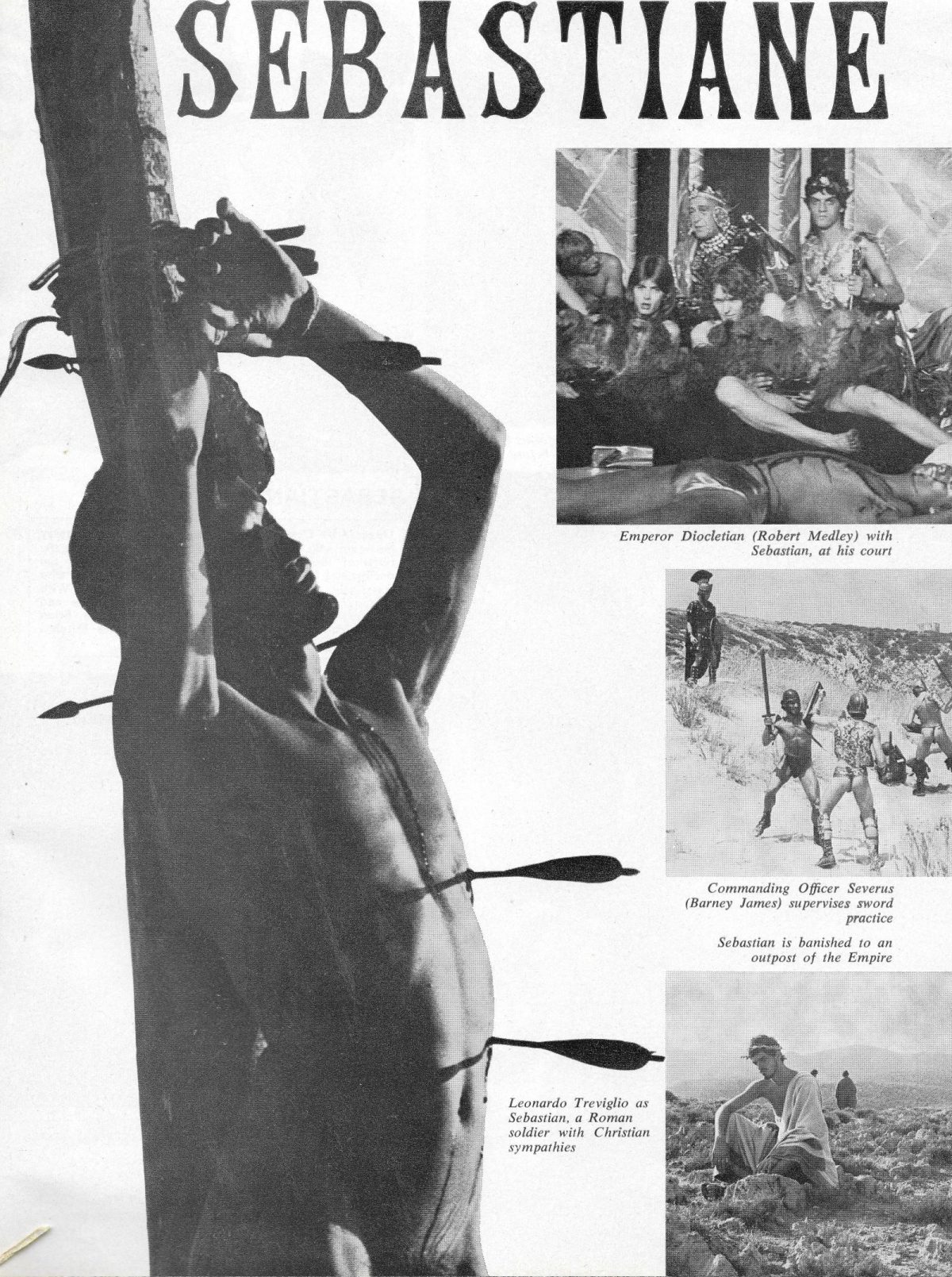

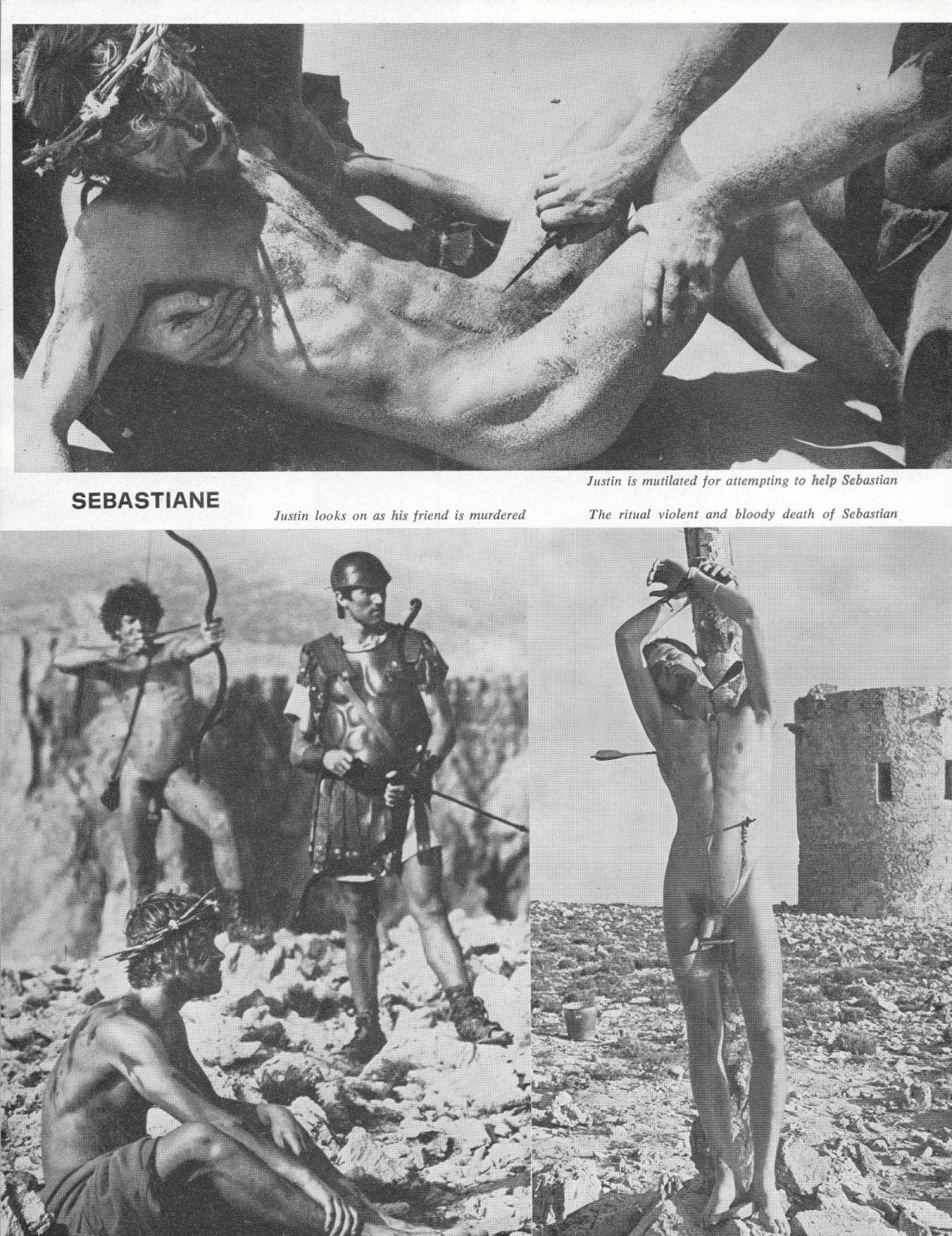

Saint Sebastian (c. AD 256 – 288) was an early Christian saint and martyr who was sentenced to death for his Christian faith by the Emperor Diocletian. Sebastian was tied to a tree and shot full of arrows. According to legend he did not die but his wounds were healed by Saint Irene of Rome. Sebastian then returned to Diocletian’s court and reprimanded the Emperor before he was beaten to death with clubs.

In Jarman’s version of the story, Sebastian is a Sun worshipper and a pacifist, who stops one of Diocletian’s servants strangling a Christian. For this, Sebastian is exiled to a Roman military outpost where he refuses to give up his beliefs or fight for the Roman Empire. For this he is sentenced to death.

The autobiographical centre to Jarman’s movie came out of an incident from his time at public school. According to his biographer, Tony Peake, Jarman was once sexually abused at school. During a line-up where naked teenage boys presented themselves for examination by the school doctor to check their worthiness to serve in Her Majesty’s Armed Forces, a warm hand cupped testicles as the doctor asked each pupil to cough. Jarman felt humiliated by such (a degrading) examination. But it wasn’t the sense of humiliation which caused the most hurt. It was the fact Jarman had an exceedingly large penis which led his classmates to nickname him Horse, Horse Man, Hose Man and Hose. Peake claims that one day these fellow classmates stripped Jarman and brought him to orgasm with a feather duster. It was an event which excited yet mortified Jarman. Years later he Steede he had been “raped”. Whichever version is true, the actions of a few classmates affected Jarman for life.

Jarman saw himself as Sebastiane. A man punished for being “other”. He wrote a script and collected together a band of friends and accomplices who travelled to Sardinia to make a film. The cast included Richard Warwick, co-star of Lindsay Anderson‘s film If… and Barney James, drummer with the Rick Wakeman Band, Frank Zappa, John Martyn, P. J. Proby and Herbie Hancock.

James, who died in 2016, recounted his time working with Jarman in 2010:

The cast and crew are assembled at Derek Jarman’s apartment in London, prior to leaving for the airport. Government policy at the time limited the amount of actual cash you could take out of the country, so ‘The Producers’ of the film hatched a plan, each member of the cast would secrete huge amounts of cash about their person. I don’t know the collective amount, but I did know that if we were searched, it was straight to jail.

We fly to Sardinia via Rome without incident and check into our hotel in Cagliari a small village on the southern tip of the island. The next morning the costume truck arrived and we are all decked out in Roman armour and togas. I’m delighted to be wearing Richard Burtons costumes as featured in the epic Antony and Cleopatra. But, there’s a setback, the people of the village are an inquisitive lot and are hellbent on finding out the nature of our business there.

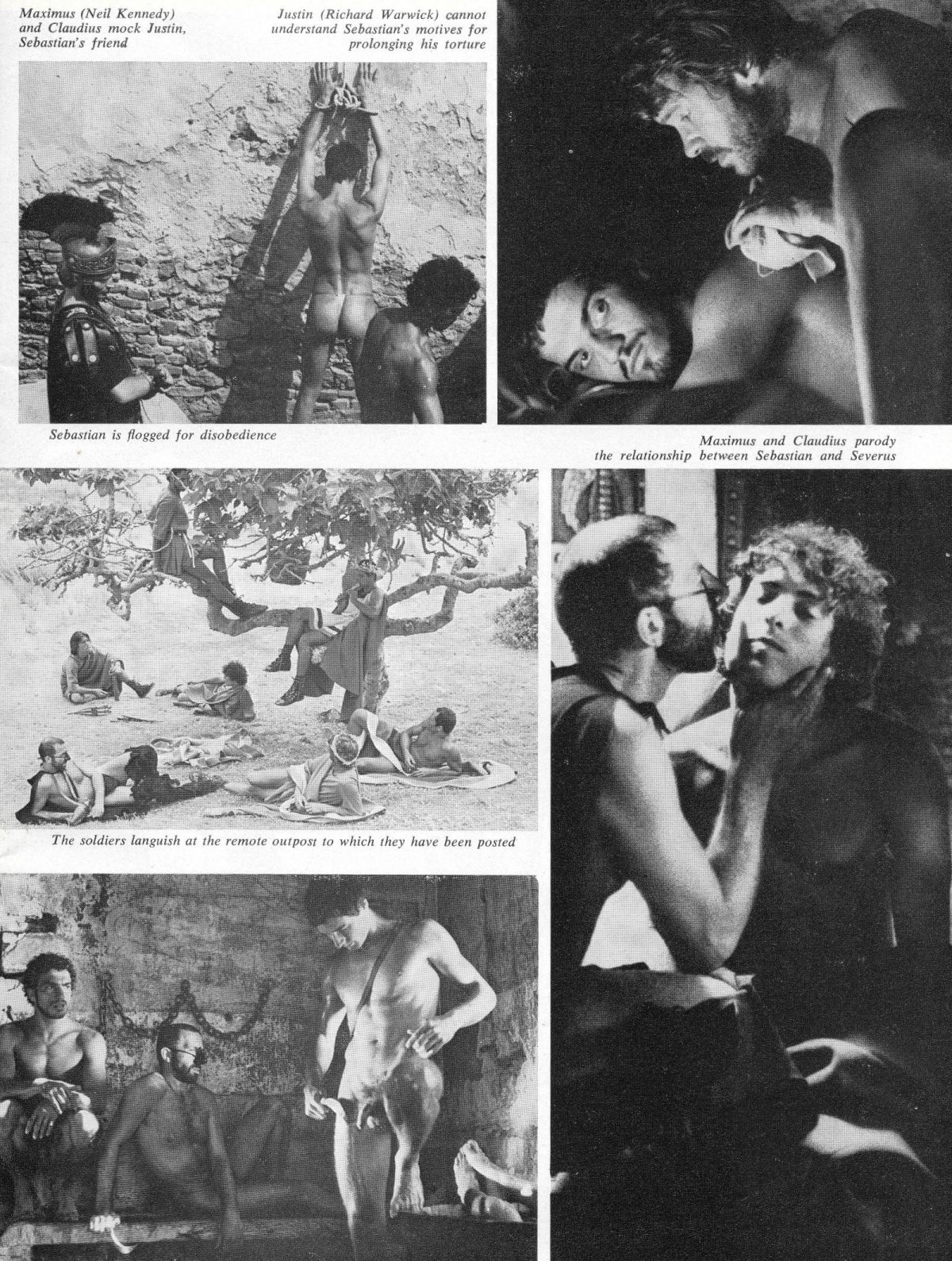

Derek Jarman’s film Sebastiane centres around a young Pretorian centurion during the reign of Emperor Diocletian in 32 AD Rome [sic]. The centurion, or St. Sebastian as we now know him, is a favourite of the emperor, who becomes enraged when his young lover turns to Christianity. The senate in Rome would have Sebastian thrown to the lions, however, the emperor is more lenient and simply banishes Sebastian to an outpost far from Rome. Once there, he falls amongst a motley crew of exiles under the command of Severus, a brutal centurion. The story culminates in the death of Sebastian, an iconic figure depicted throughout the ages as a homoerotic figure, naked and tied to a wooden stake then shot through with arrows.

The controversy of the films content would have had the Italians up in arms, so a way of placating the local feeling had to be made. Once again up step ‘The Producers’ and some more of their illicit practises. A press conference is called at which the producers simply lied through their teeth, saying that the movie was a semi-doc centring around early Roman occupancy of Sardinia. I was then approached by ‘The Producers’ to deploy other session musicians to the island and perform a free concert by way of a diversion. Despite the minor setbacks, filming continued at a pace with instructions to never mention the S word.

Tales of excess reached the local police who visited the filmmakers on location. Jarman and Whalely explained they were just a bunch of students making a student film. A few drinks, a few jokes, and all seemed smoothed over. Yet the suspicion from locals that these English students were up to no good persisted. This was not helped by co-director Paul Humfress claiming Jarman was “a pornographer” after on one offscreen incident as Tony Peake described it in biography on Jarman:

…in the love scene between Adrian (Ken Hicks) and Antony (Janusz Romanov), there had been technical difficulties of a different order. Hicks insisted on sporting an erection, but did not fancy Romanov enough to produce one. Eventually Gerald Incandela came to the rescue, hurrying Hicks behind a rock to achieve the desired effect, which caused Paul Humfress to accuse Jarman of being a pornographer. It was an accusation Jarman hotly denied, though there can be no doubt how thrilled he was to have a hand, so to speak, in the first hard-on ever to appear in a British feature.

This on-screen erection caused some notoriety when it was accidentally broadcast on Channel 4 during the introduction to the film by a film critic (was it really Alexander Walker…?) Sequences from the film were broadcast behind the presenter during his introduction. One sequence had not been “panned and scanned” and clearly revealed Hicks’ erection.

Returning to the UK, Jarman realised he did not have enough material for a feature film. It was decided an opening sequence set in Diocletian’s court would be added. Jarman roped in friends and allies like Lindsay Kemp, Andrew Logan, Duggie Fields, Robert Medley, cast members from The Rocky Horror Picture Show Little Nell and Peter Hinwood, and punk icon Jordan. Kemp performed an impromptu dance sequence writhing in front of a group of dancers with enormous wooden phalluses which fired a mix of yoghurt and wallpaper paste over Kemp. Jarman described this as “a condensed milk orgasm”. The dance sequence took up most of the filming schedule. This meant the scenes from the court of Diocletian were reduced to a few minutes. But at least Jarman had a finished movie.

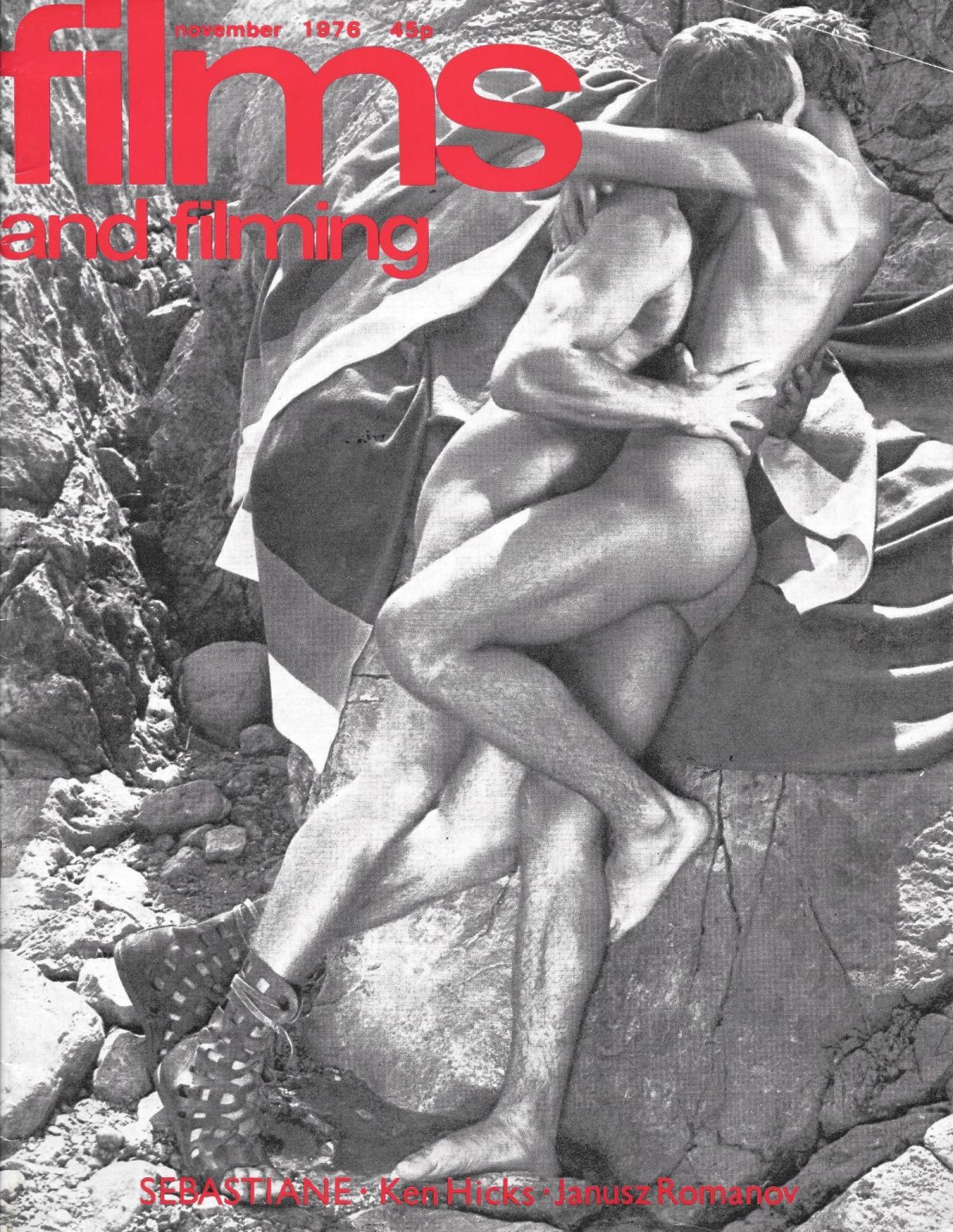

Released in December 1978, Sebastiane received mixed to negative reviews. Films and Filming (surprisingly) described the movie “as exclusively homosexual, and as a hymn to the male Eros…”

Certainly, the camera is permitted plenty of time on which to contemplate its subject, and the makers have gone to considerable lengths to recreate their own equivalents of such heterosexual Pirelli calendars as Emmanuelle or Histoire d’O

[~~snip~~]

…Sebastiane seems to me to be merely high-class underground, of limited audience appeal and with the novelty value in the Latin dialogue. And definitely not fit for your child who is struggling through Caesar’s Gallic Wars (Book One) at school.

Tony Rayns was far more prescient in his review of Sebastiane in Monthly Film Bulletin #43 1976 when he described the film as “[t]he most promising sign of new film life in independent narrative cinema in [Britain] in many, many years.”

Sebastiane brought homosexuality out into mainstream cinema and treated it as other movies had long treated heterosexual relationships. There was nothing shameful about it. Yet, the images presented of homosexual love were complex and not as simple as a Hollywood boy-meets-girl flick, and the film has (as Jarman claimed) “altered people’s lives.” It also set a template for Jarman’s future films through tableaux and freewheeling sequences as later seen in Jubilee, The Tempest, Caravaggio, The Last of England, and The Garden.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.