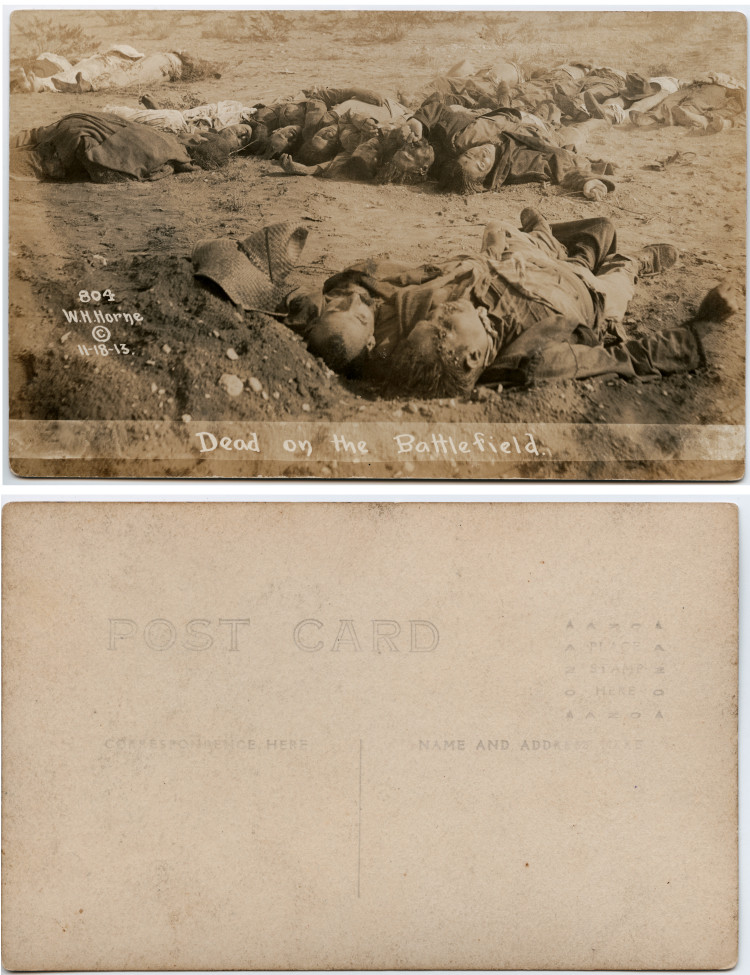

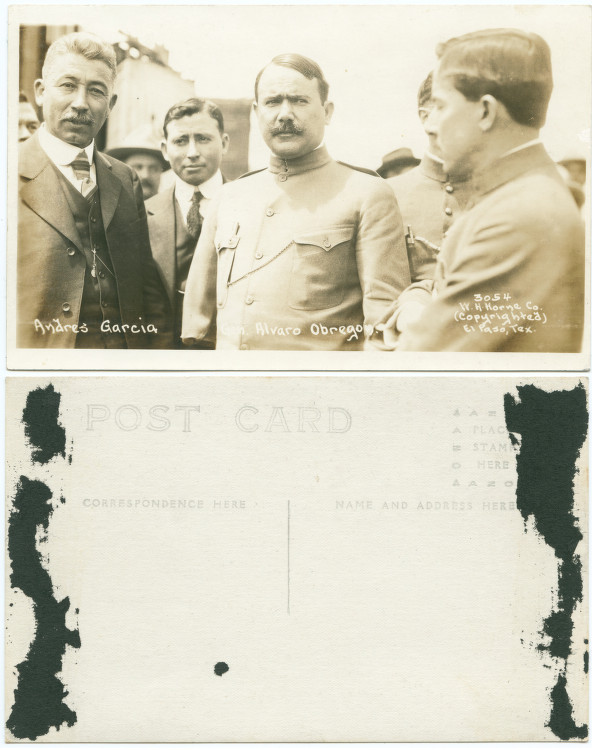

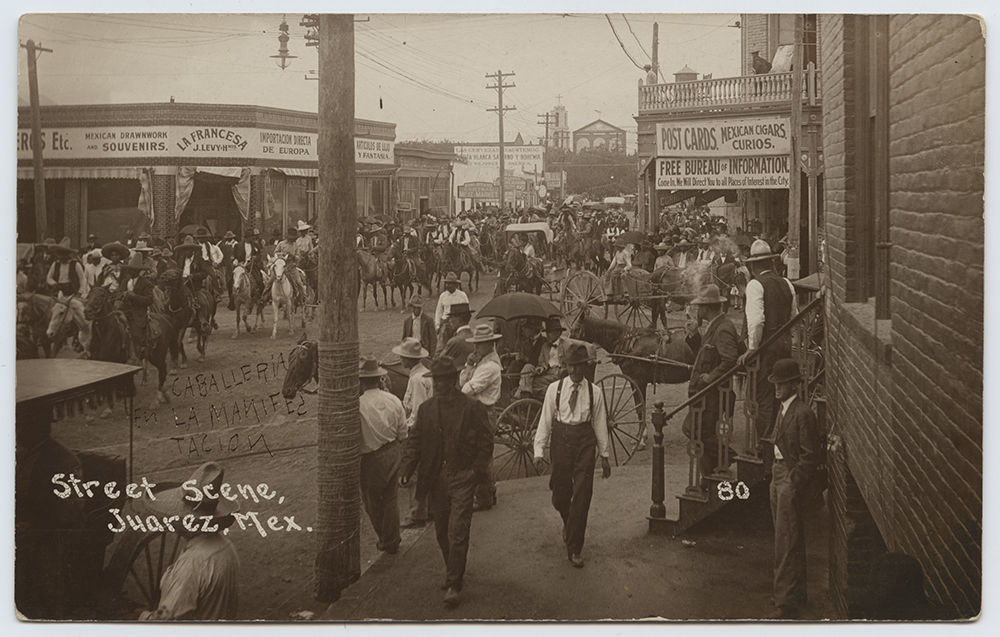

Would you send a postcard featuring the picture of a dead body of a pile of charred corpses? In this gallery we look at unusual and unsettling postcards from the Mexican Revolution, held by the DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University. Some of the postcards from 1910-1920 show dead bodies, the remains of people executed in judgement and killed in combat. To call the pictures grim is to make an understatement. They might be ghoulish and voyeuristic, but they are valid historical records and curios. We don’t know what you’d write on the reverse – ‘Wish you were here!’ is unlikely, even when steeped in pitch-black humor. You can write anything you like on a postcard, or nothing at all. We can debate their purpose – was it to convey to the people back home the horrors of war? To titillate? To provoke? Are the postcards without artifice, snapshots of the banal? If life seen through a lens economises the truth is choosing death for a subject an effort to produce something as close to unquestionable fact as a photograph can achieve? Or are the pictures stylized, allowing us to ‘see how something looks photographed’, designed to reflect the uncertainty and chaos of war?

They can certainly make us think.

As said, the images hereunder are grim.

Many of the photographs were taken by Walter H. Horne, regarded as documentary photographer.

Leonard Folgarait, Professor of History of Art at Vanderbilt University, has written about how such brutal photographs help to define a national identity for Mexico. “Photographs are quotations of time, edits out of the historical whole, seeming to picture events only,” he writes. “I want to suggest that they also picture conditions. How the Revolution changed from an event of some precise duration to a condition, an image, of infinite historical extension, is strongly related to the behavior of photography.”

…

“Photographs have to be seen as historical events themselves, not so much linked to context as much as being context all along, forming that context as much as did other sorts of events, such as battles, speeches, or printed documents.”

Photographs turn the present into past, make contingency into destiny. Whatever their degree of “realism,” all photographs embody a “romantic” relation to reality.

I am thinking of how the poet Novalis defined Romanticism: to make the familiar appear strange, the marvelous appear commonplace. The camera’s uncanny mechanical replication of persons and events performs a kind of magic, both creating and de-creating what is photographed. To take pictures is, simultaneously, to confer value and to render banal.

– Susan Sontag, Portraits in Life and Death

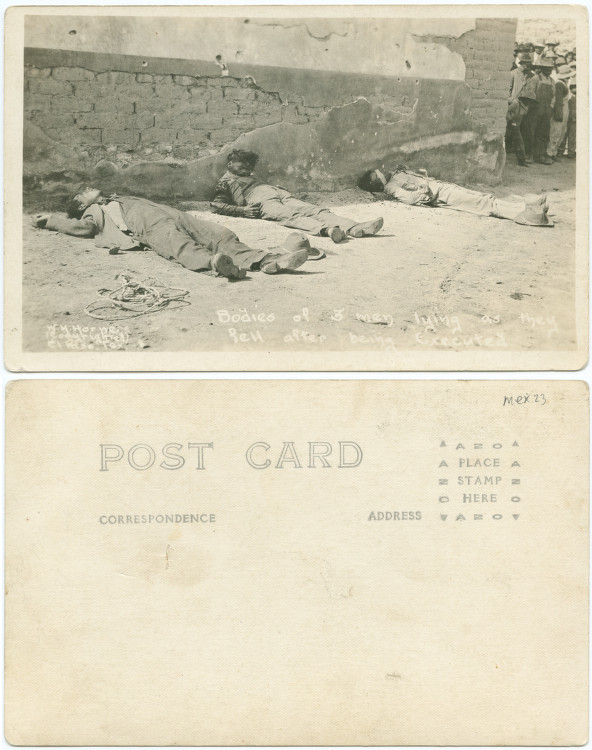

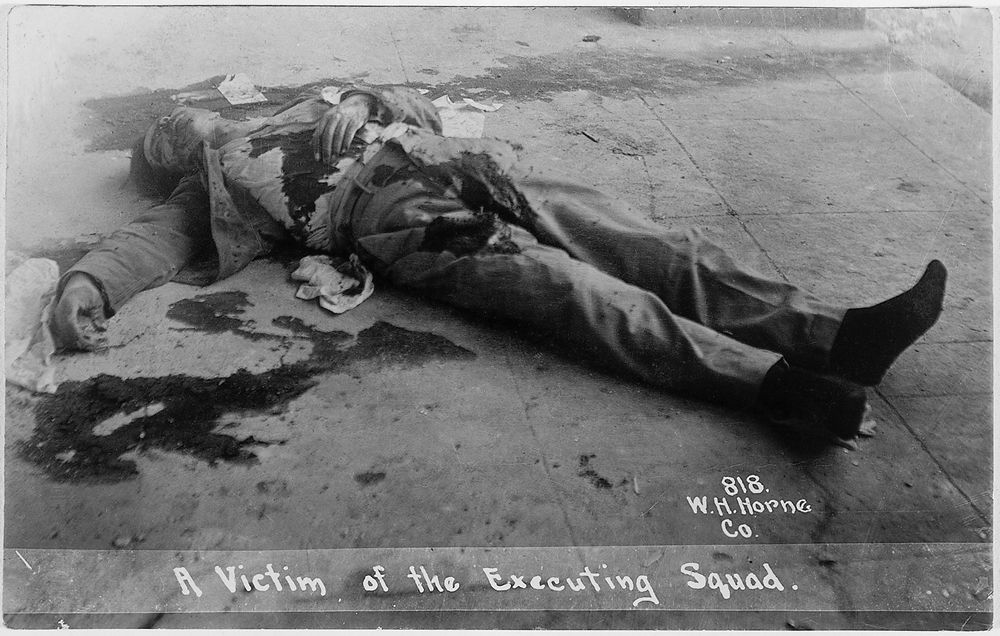

Bodies of 3 men lying as they fell after being executed.

Title: Bodies of 3 men lying as they fell after being executed.

Creator: Horne, Walter H., 1883-1921

Date: January 15, 1916

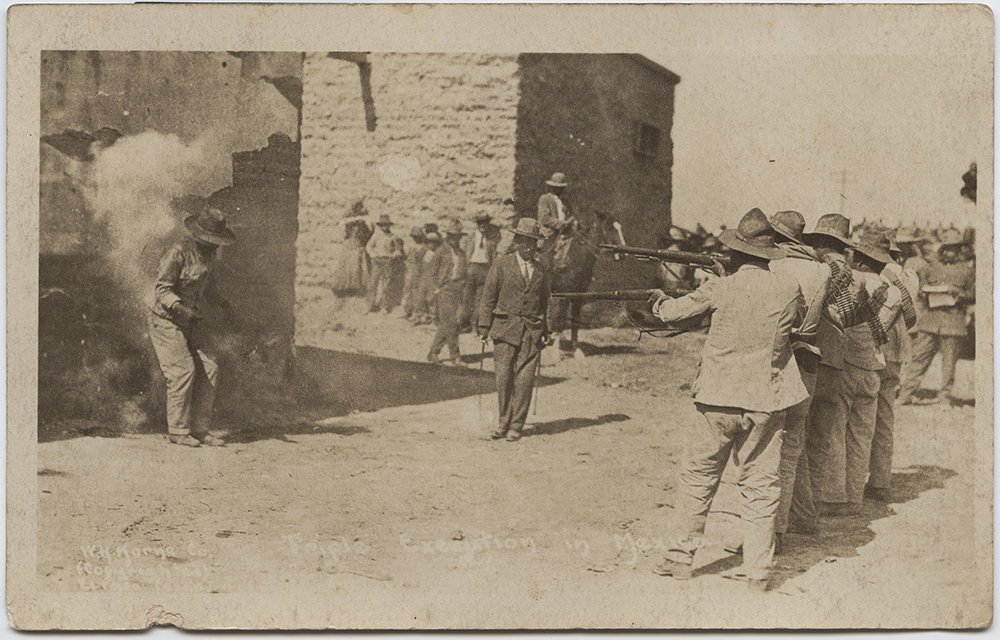

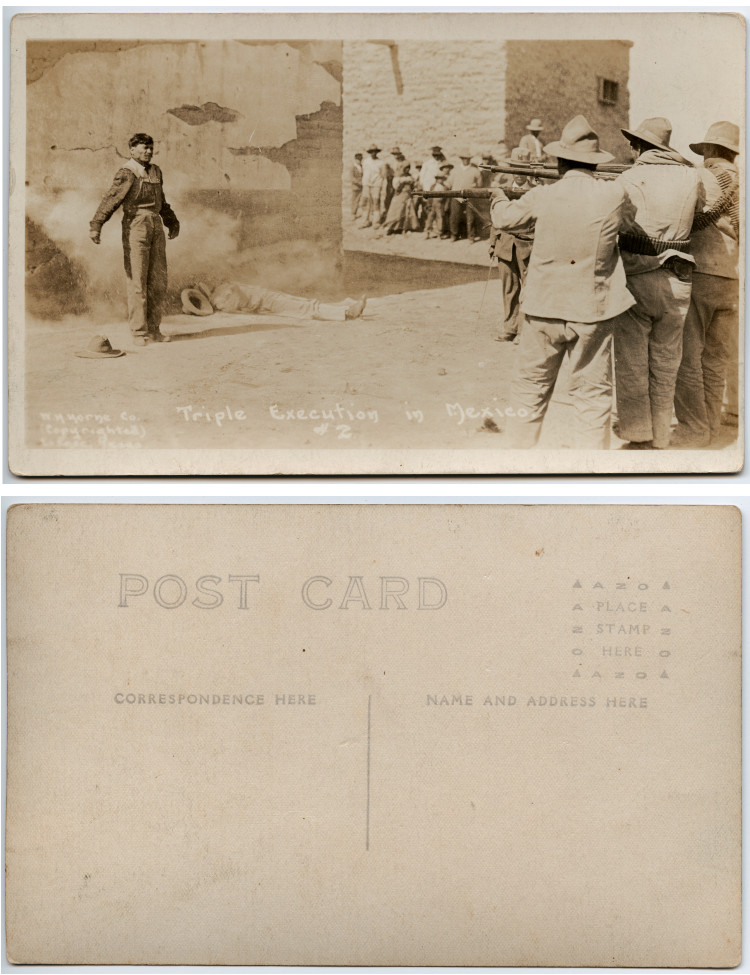

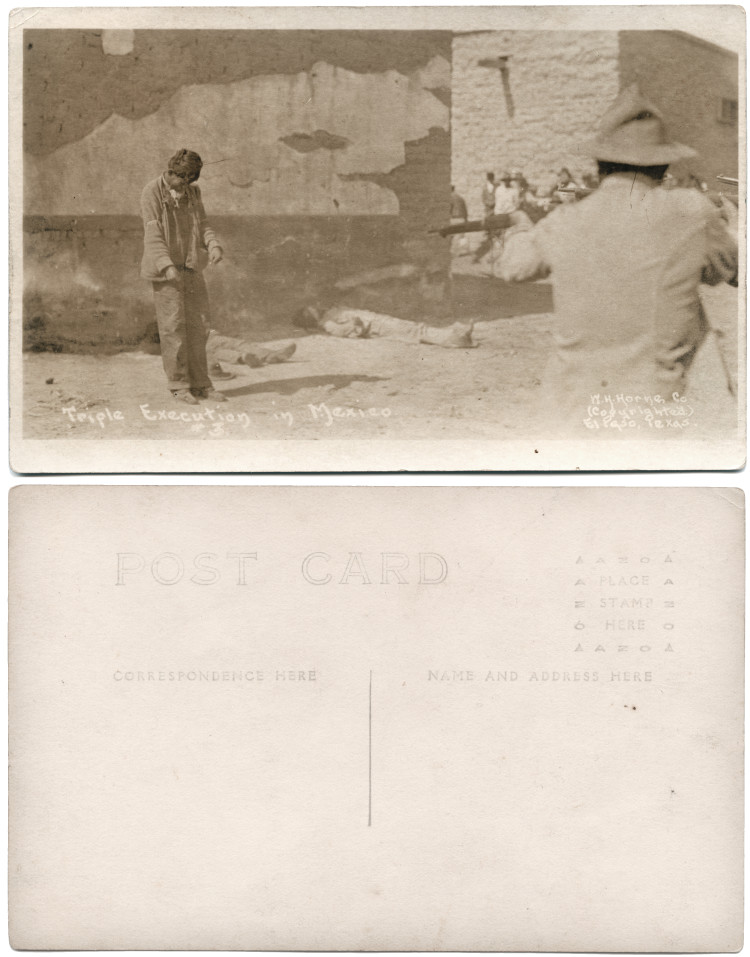

Triple execution in Mexico

Title: Triple execution in Mexico

Creator: Horne, Walter H., 1883-1921

Date: January 15, 1916

Place: Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, Mexico

Part Of: Collection of Walter H. Horne photographs

Series: Triple Execution in Mexico Series

Description: This image is one of a group of photographs by Horne known as the ‘triple execution’ series. It depicts the execution of three condemned prisoners for allegedly stealing military supplies. The victims, Francisco Rojas, Juan Aguilar and Jose Moreno were executed on January 15th, 1916, at the Northwest Railroad Station, in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. (Vanderwood and Samponaro 1988, 68)

![Title: [Mexican soldiers, one aiming rifle and one on horseback] Creator: W. F. Stuart Date: ca. 1910-1917](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Mexican-war-postcards-40.jpg)

Title: [Mexican soldiers, one aiming rifle and one on horseback]

Creator: W. F. Stuart

Date: ca. 1910-1917

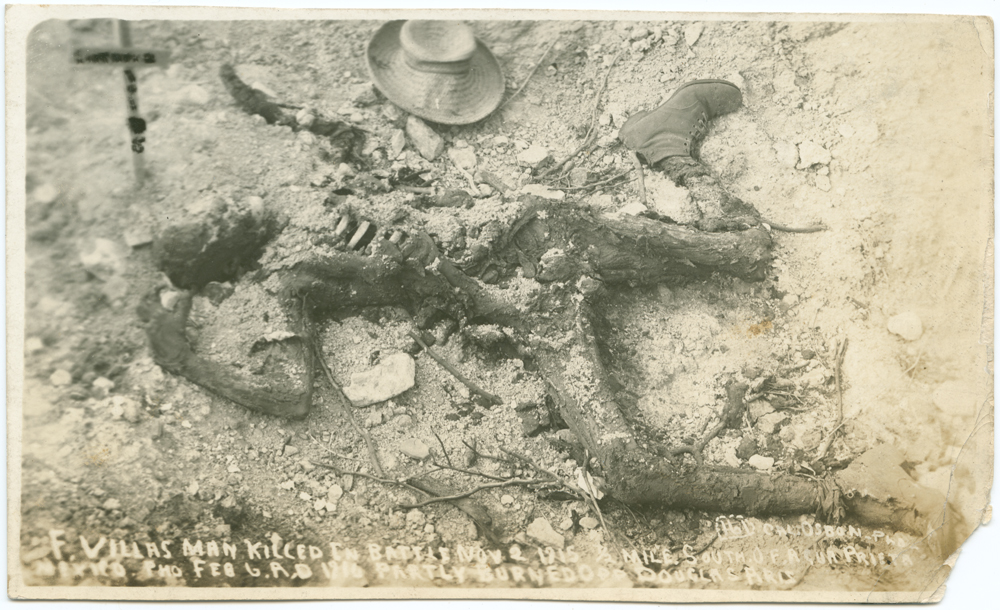

Title: F. Villas man killed in battle Nov 2, 1915 1/2 mile south of Agua Prieta Mexico.

Creator: Osbon, Cal (Calvin C.), 1849-1924

Date: February 6, 1916

![Title: F. Villas men. These men was executed too [sic] miles op. Agua Prieta Mexico. Jan 1916. Creator: J. Snow Date: February 8, 1916](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Mexican-war-postcards-27.jpg)

Title: F. Villas men. These men was executed too [sic] miles op. Agua Prieta Mexico. Jan 1916.

Creator: J. Snow

Date: February 8, 1916

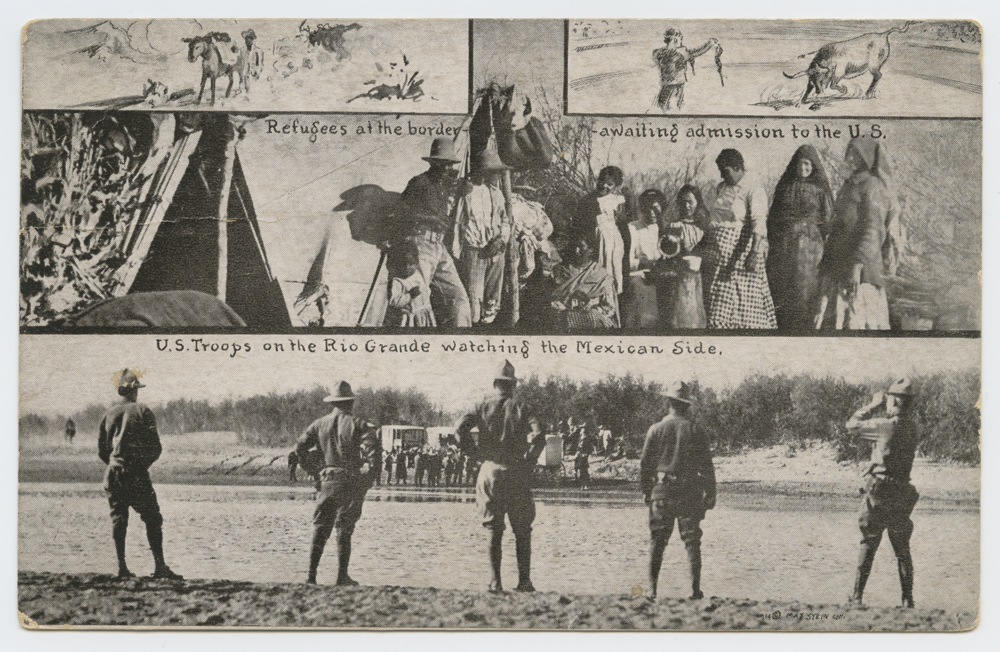

Title: Refugees at the border – awaiting admission to the U. S., U. S. Troops on the Rio Grande watching the Mexican Side.

Creator: Unknown

Contributors: Stein, Mex (publisher)

Date: 1914

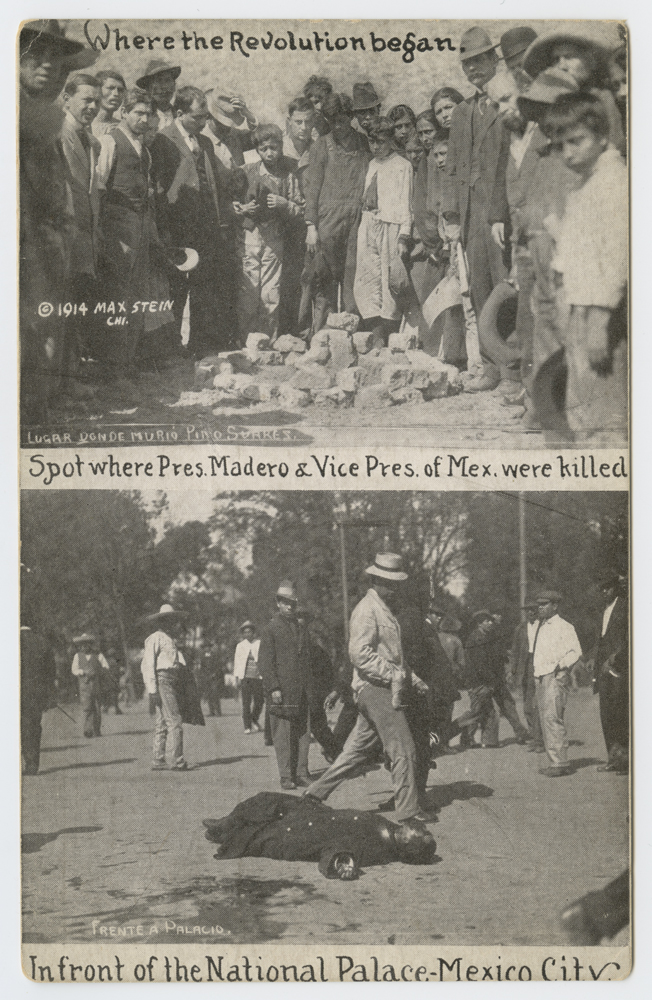

Title: Spot where Pres. Madero & Vice Pres. of Mex. were killed, In front of the National Palace – Mexico City.

Creator: Unknown

Contributors: Stein, Max (publisher)

Date: 1914

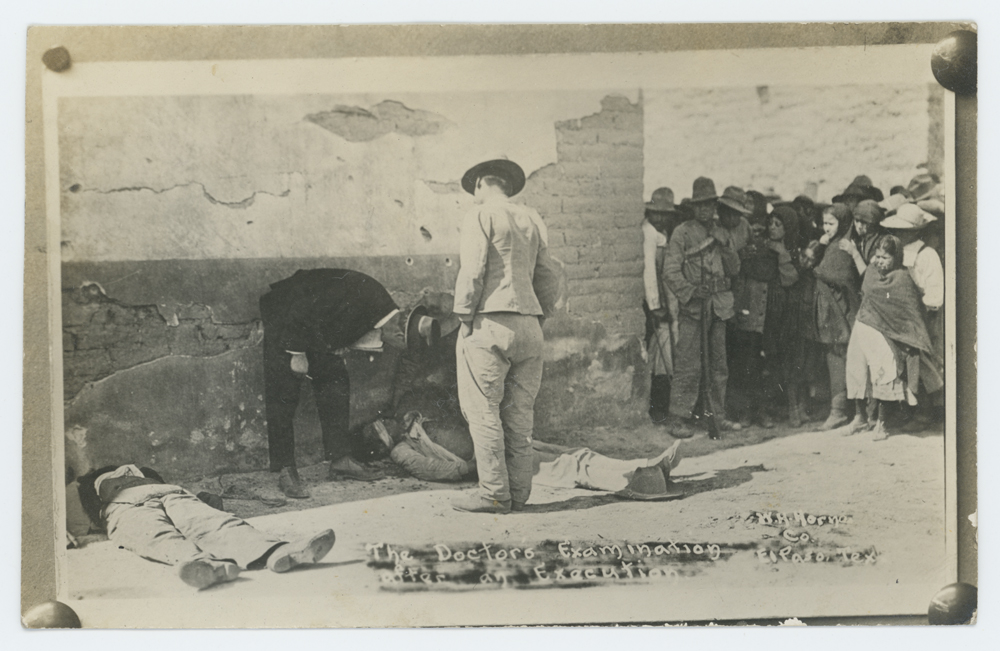

Title: The Doctor’s Examination after an Execution.

Creator: Horne, Walter H., 1883-1921

Date: January 15, 1916

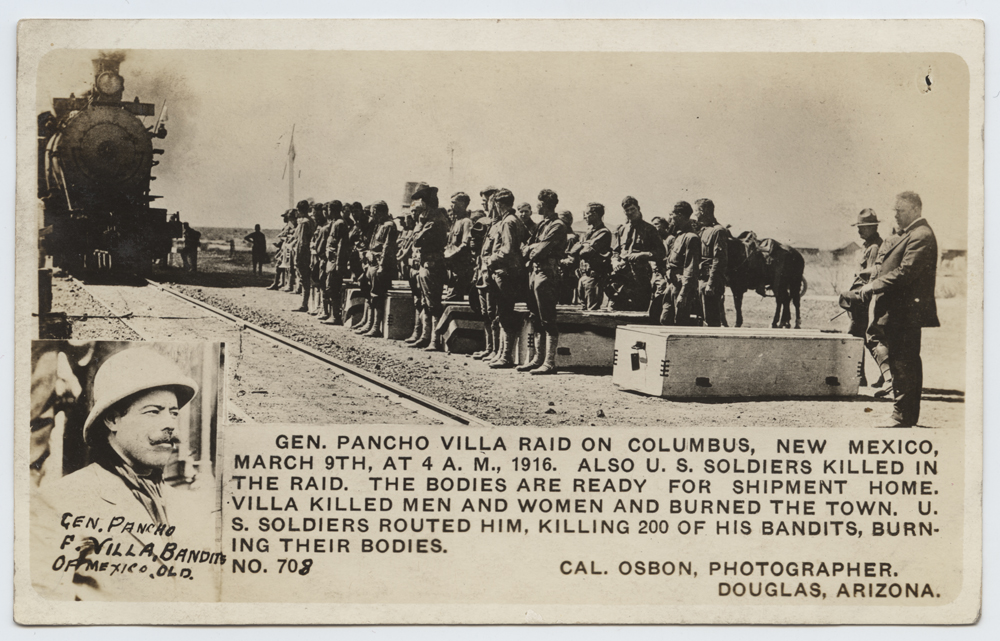

Title: Gen. Pancho Villa Raid on Columbus, New Mexico, March 9th, at 4 A.M., 1916.

Creator: Osbon, Cal (Calvin C.), 1849-1924

Date: ca. 1910-1918

Title: Federal Mexican firing line corner – calle Independencia at Hotel Diligencias, first day Apr. 21

Creator: Hadsell

Date: ca. April 1914

Title: Sand Storm in Training Camp.

Date: ca. 1916-1917

Creator: Osbon, Cal (Calvin C.), 1849-1924 [attributed]

Date: November 2, 1915

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.

![Title: [Mexican man kneeling beside dead body] Creator: Unknown Date: ca. 1910-1917](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/6211347747_aefb2c8bc4_o.jpg)

![Title: [Dead bodies on a Mexican battlefield] Creator: Horne, Walter H., 1883-1921 Date: 1913](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Mexican-war-postcards-52.jpg)

![Title: [Dead bodies on a Mexican battlefield] Creator: Horne, Walter H., 1883-1921 Date: 1913](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Mexican-war-postcards-51.jpg)

![Title: Yncineracion de cadaveres en Balbuena Creator: Tinoco, Samuel [attributed] Date: 1913](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Mexican-war-postcards-32.jpg)

![Title: Orozco Creator: Horne, Walter H., 1883-1921 [attributed] Date: 1915](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Mexican-war-postcards-7.jpg)