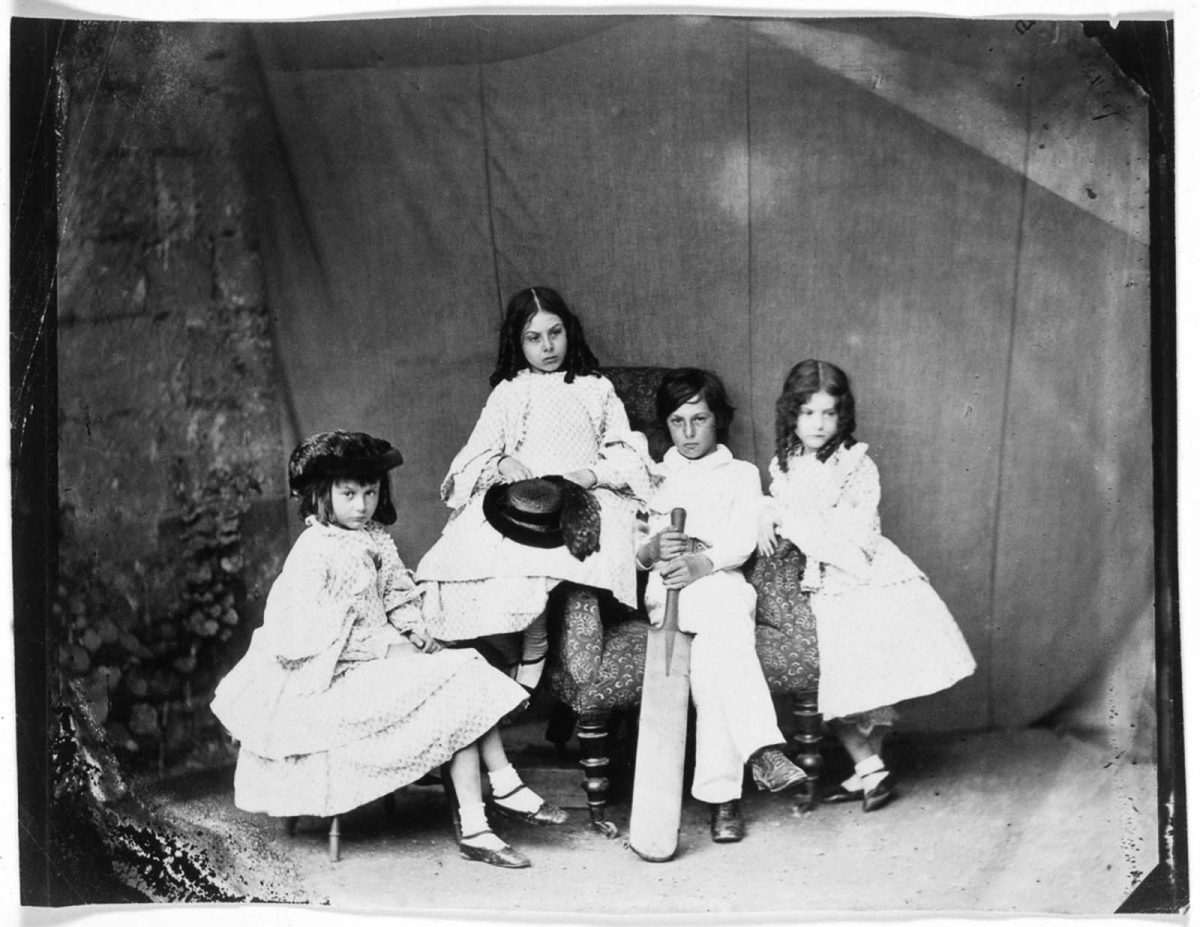

Yes, Virginia, there is an Alice—or there was, at any rate, though she did not go to Wonderland but boating on the Thames with her sisters Edith and Lorina, the Rev. Robinson Duckworth, and Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, known to readers around the world as Lewis Carroll. The Liddell sisters were the daughters of Henry George Liddell, Dean of Christ Church at Oxford, whom Carroll met while indulging his interest in photography in 1858.

Becoming close family friends with the Liddells, the writer and mathematician snapped several photographs of Alice and her sisters over the next few years and often took them on outings and entertained them. On July 4th, 1862, the day was warm, and the boating party stopped to take tea on a shaded bank. Alice Pleasance Liddell, ten years old at the time, “implored Carroll to ‘tell us a story,’” notes the University of Maryland Library.

According to Carroll, “in a desperate attempt” and “without the least idea what was to happen afterwards,” he sent his heroine “straight down a rabbit-hole.” Upon Alice’s urging, Carroll began writing down his tale. On November 26, 1864, he presented her with an elaborate hand-illustrated manuscript, titled Alice’s Adventures Under Ground.

The following year, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was published and “Alice Liddell became immortalized as the inspiration for Carroll’s much-loved character.” John Tenniel’s famed illustrations in the first edition do not resemble Alice Liddell (nor did Carroll’s original drawings), but her influence on the story has never been in doubt. “Alice was no ordinary muse,” remarks her descendent Vanessa Tait. “She nagged, bossed and bullied Dodgson into writing down her story,” and in so doing she left a huge footprint on literary history.

But Alice moved on from the childhood fantasies Carroll encouraged. By the time the novel’s sequel, Through the Looking Glass appeared, in 1871, she was nearly 20 years old. The second book—which ends with an acrostic poem spelling out Alice’s name, “can be seen as a fond farewell to Alice as she enters adulthood,” as well as evidence of Carroll’s difficulty in letting her go. Carroll’s interest in the young Alice has sometimes been framed as less than innocent, prompting novelist Vladimir Nabokov to describe a “pathetic affinity” between Carroll and Humbert Humbert, the depraved narrator of Lolita.

On the other hand, photographing young children, even children in the nude or posed suggestively—as in the 1858 photo of Alice as “the beggar maid” above—was a widespread practice in the 19th century, seen as harmless playacting and the very representation of innocence. In the photo, “Alice looks at us with faint suspicion,” writes the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “as if aware that she is being used as an actor in an incomprehensible play. A few years later, a grown-up Alice would pose, with womanly assurance, for Julia Margaret Cameron,” one of the most prominent portraitists of the century.

The Liddells met Cameron “during a family holiday in Freshwater, on the Isle of Wight,” writes the Victoria and Albert Museum. “Cameron photographed Alice Liddell and her sisters several times in the 1870s, producing some of her most remarkable work. She portrayed Alice as numerous classical figures, including the goddesses Pomona, Alethea and Ceres. As Pomona, still with her signature fringe and hand on hip, Alice Liddell appears strikingly modern. Cameron also photographed Alice and her sisters together in a pose reminiscent of The Three Graces, an ancient mythological motif depicting the daughters of Zeus. The photograph recalls early images of the three sisters in a triptych taken by Charles Dodgson – the ‘golden afternoon’ revisited.”

In 1880, Alice married Reginald Hargreaves, a student of Carroll’s, and they settled down to raise three sons. She lived a private life in luxury for the remainder of the century and did not reappear in the public eye until 1928. World War One had claimed the lives of two sons and her husband had died two years earlier. In financial straits, Alice sold Carroll’s original manuscript, though “the loss to the UK of the iconic manuscript provoked national outcry.” The sale coupled four years later with a visit to the US for the Lewis Carroll centenary at Columbia University, where she received an honorary degree, renewed her fame. She has since appeared as a fictional character in novels, plays, and TV shows.

Alice passed away in 1934. She was cremated and her ashes buried, under the name Mrs. Reginald Hargreaves, at St. Michael and All Angels church in Lyndhurst. Her manuscript was returned the UK after World War Two, “in recognition of Britain’s courage in facing Hitler before America came into the war.” It now resides at the British Library. See the complete, digitized manuscript here.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.