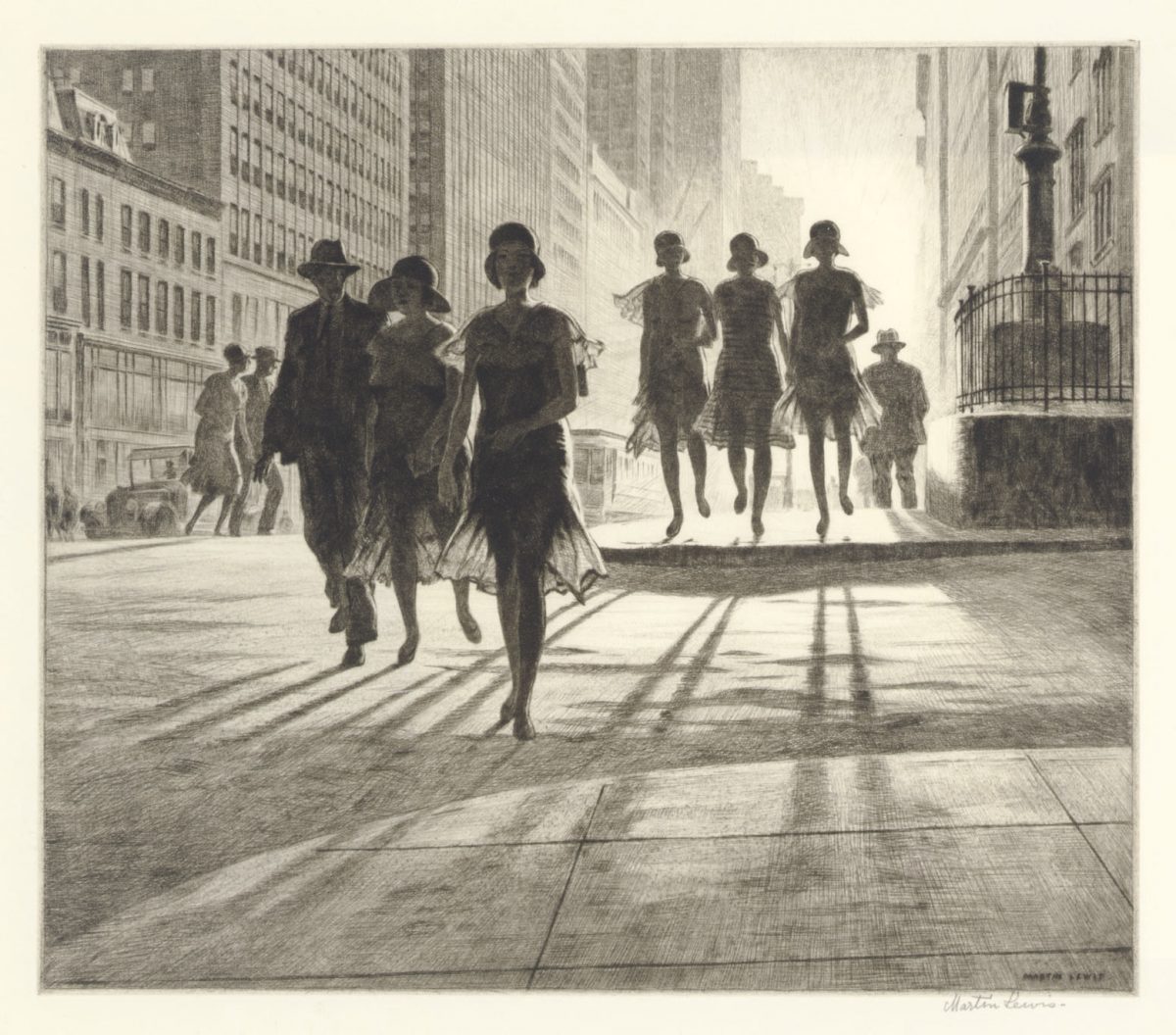

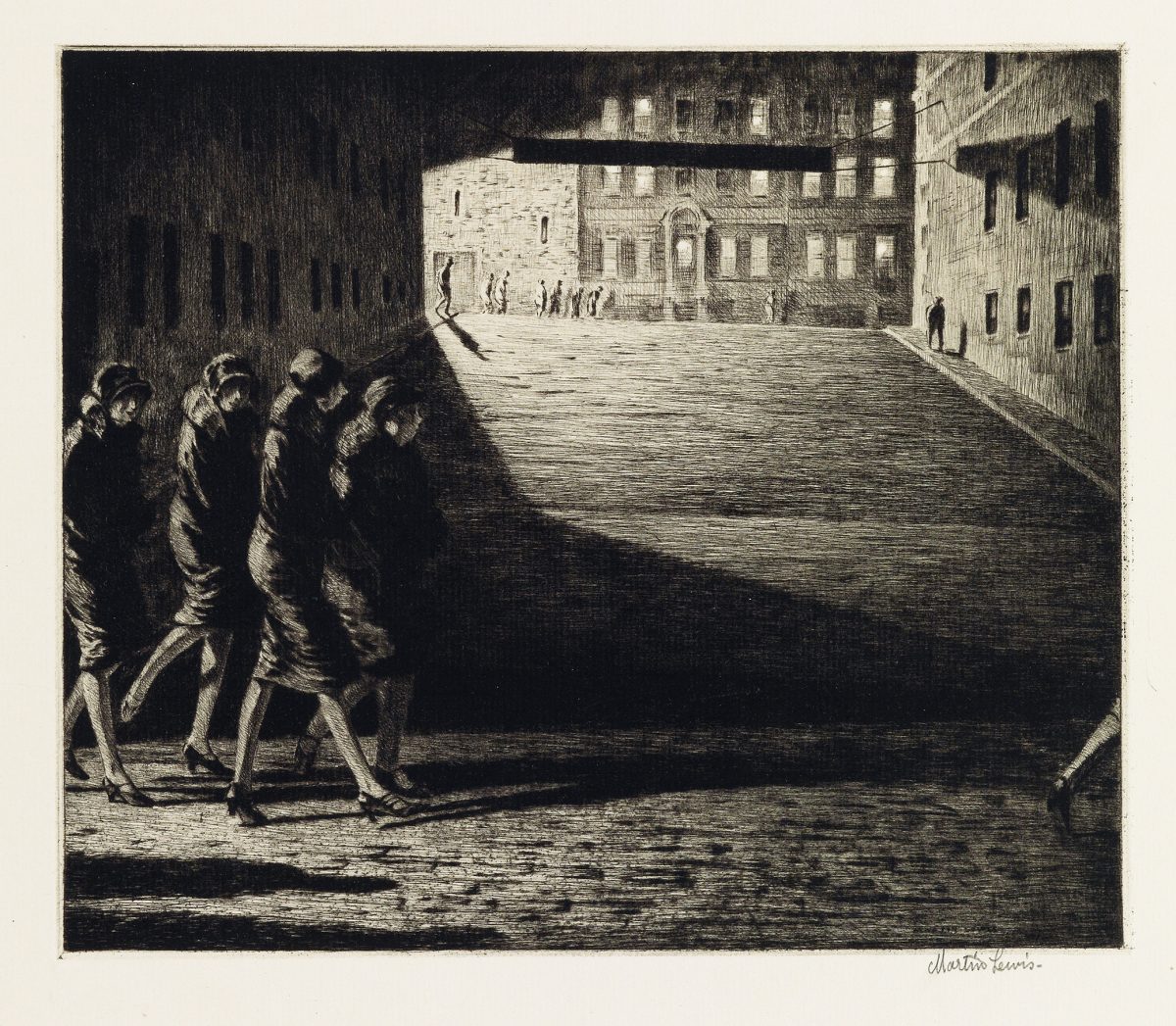

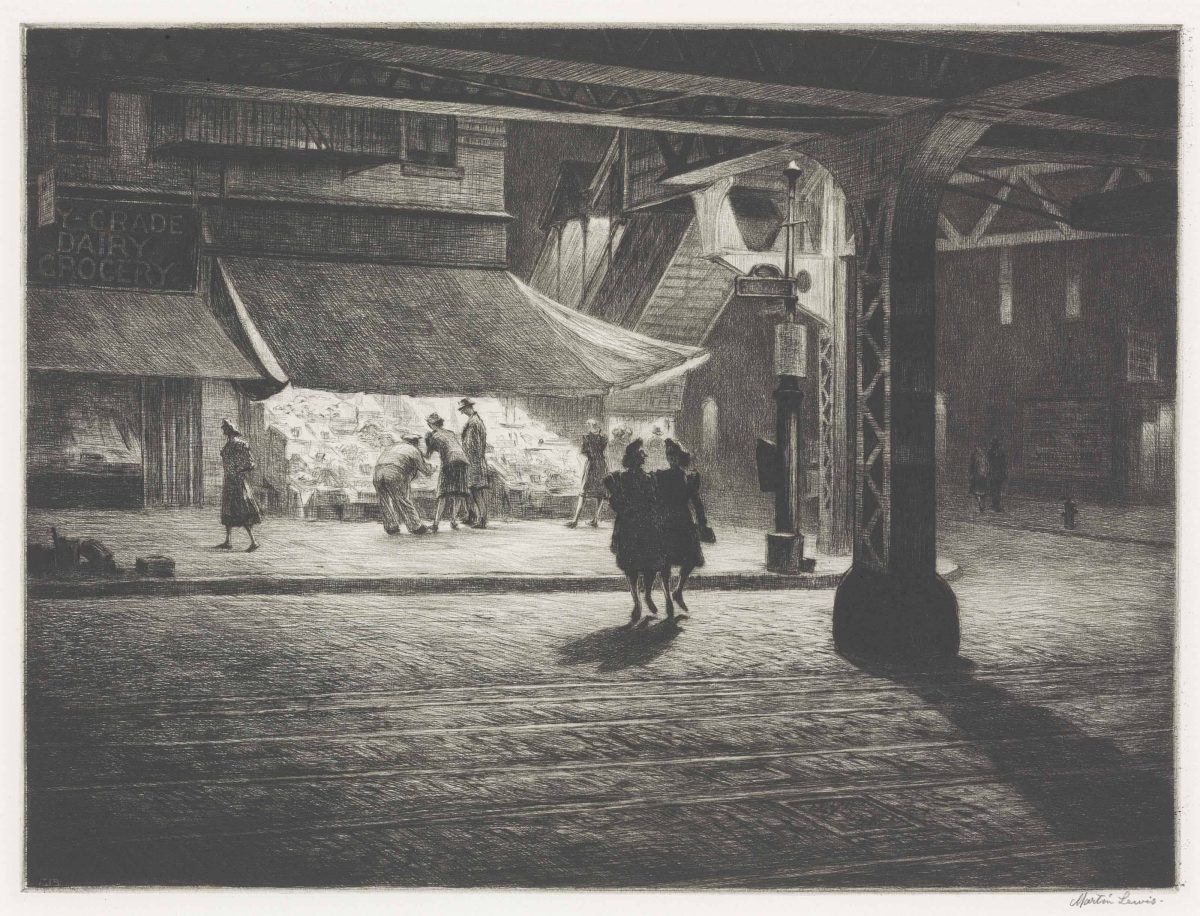

Martin Lewis – Shadow Dance – New York City

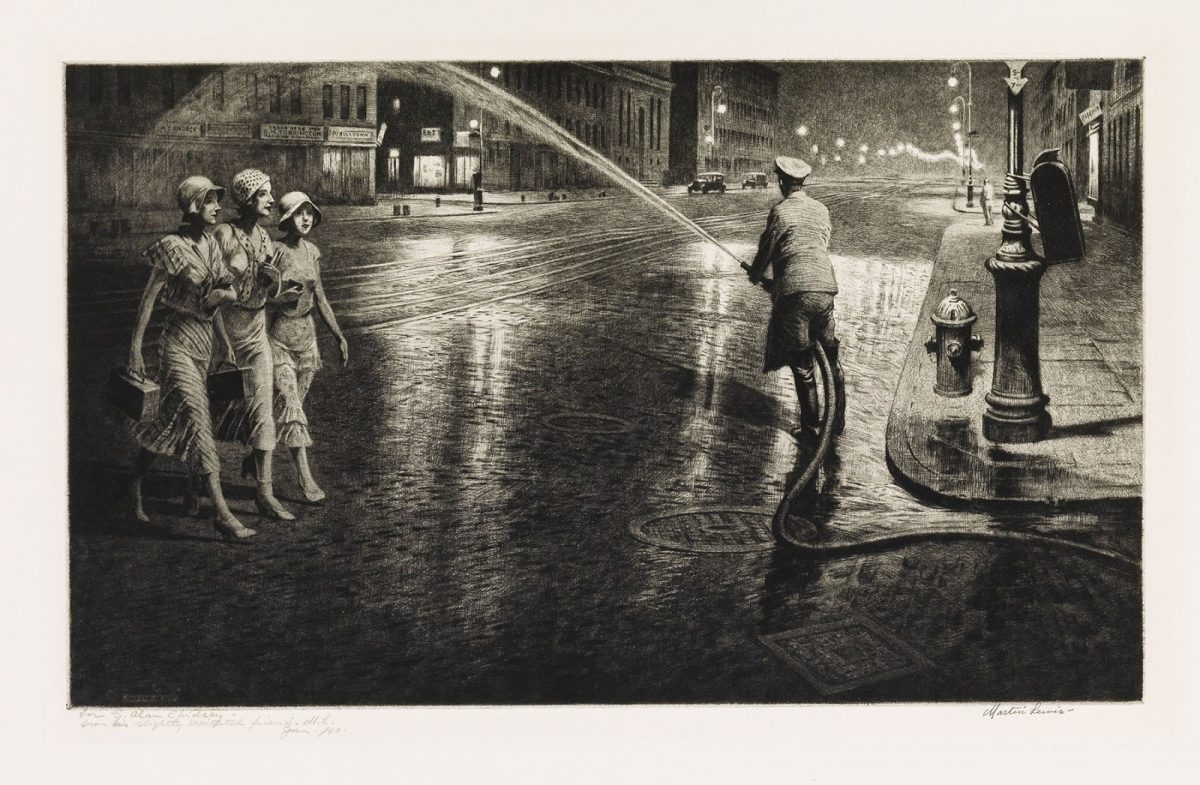

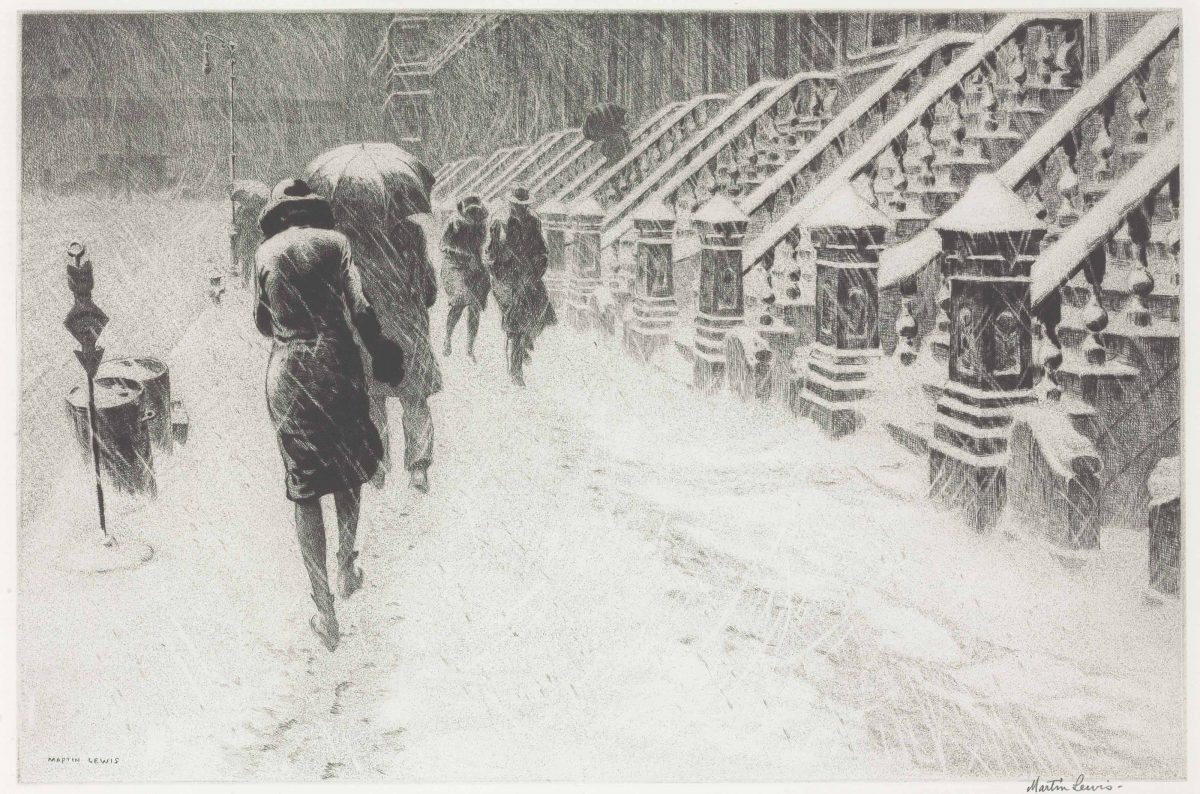

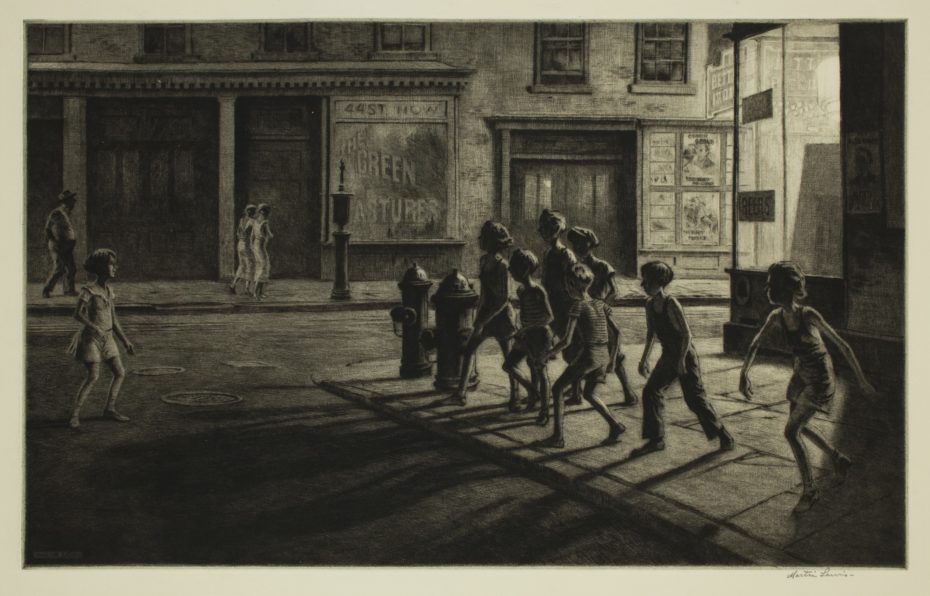

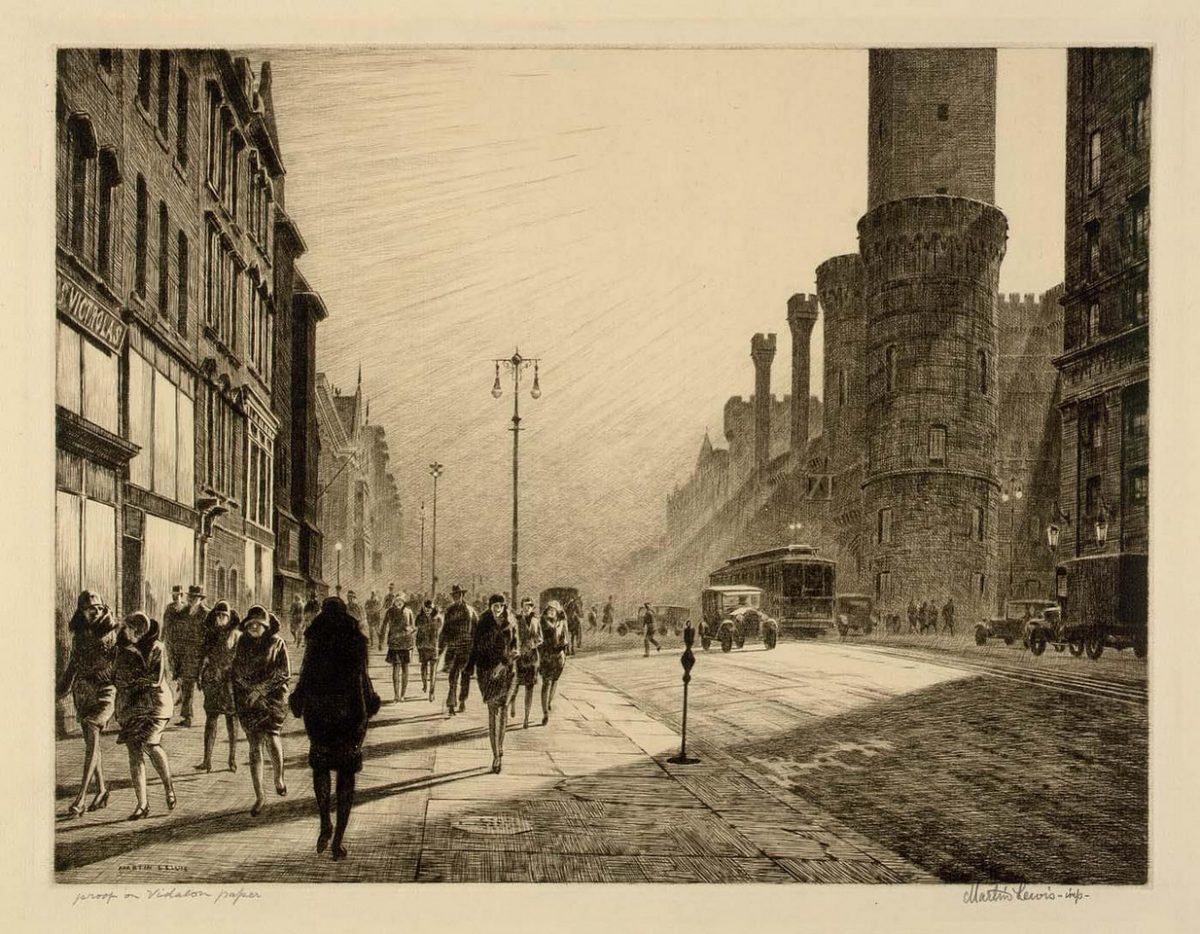

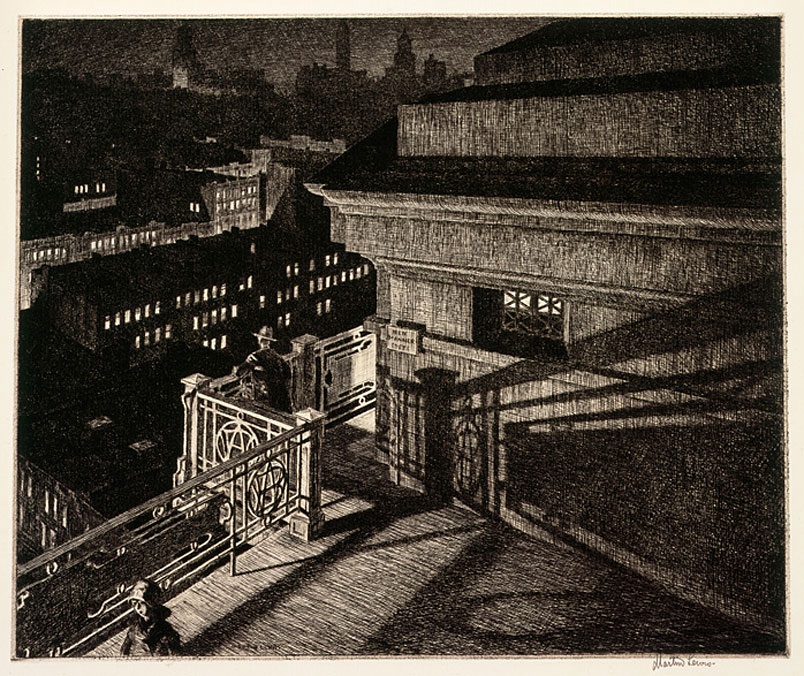

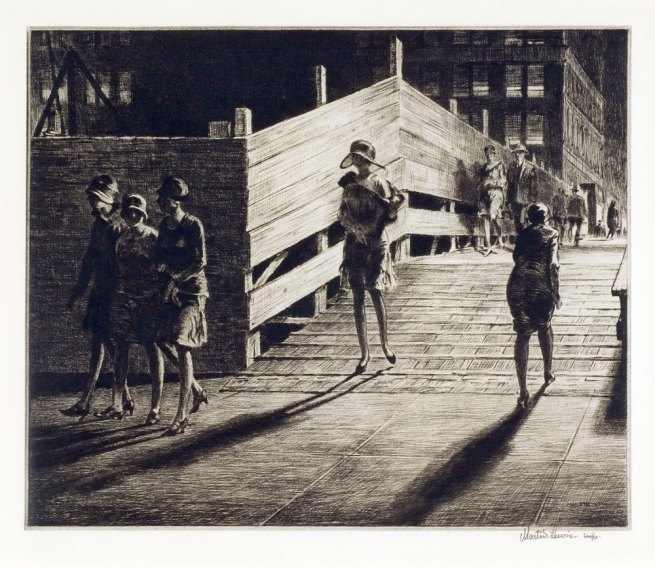

Martin Lewis (7 June 1881 – 1962), the Australian-born American printmakers and artist, is best known for his etchings of New York City. Martin captured the city’s human bustle and brooding architectural menace. We see busy people in sullen places dressed in light and shade.

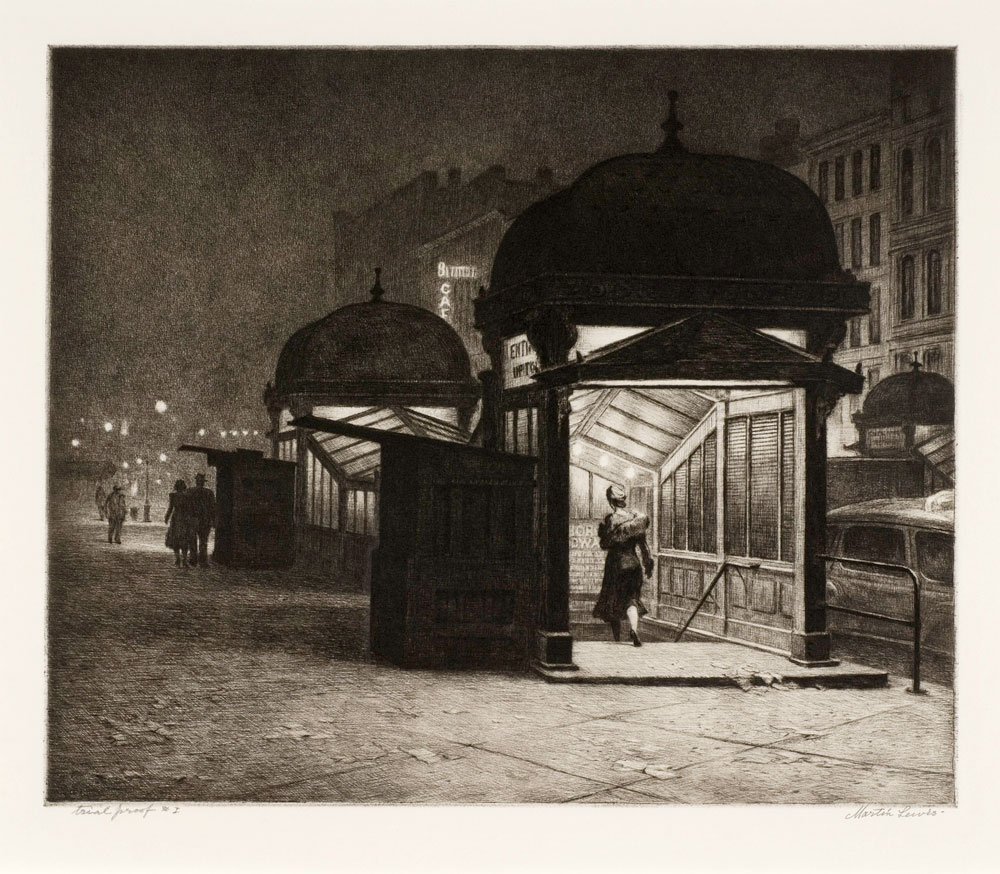

The air tingles at the sense of acute urban loneliness in his etching of a woman darting down into an otherwise empty Subway late one night. You get a sense of human isolation and failure among the thrusting, soaring New York of the planners’ dreams.

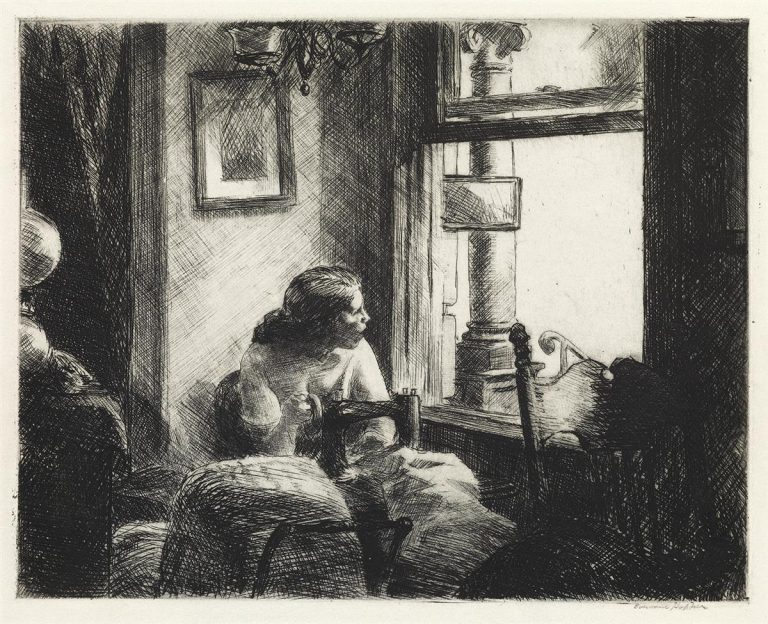

>For aded bang Lewis was briefly mentor to the great Edward Hopper (July 22, 1882 – May 15, 1967). Etching played a big part in Hopper’s career, as he opined in his autobiography: “After I took up my etching, my painting seemed to crystallise.” But if Lewis influenced the revered Hopper, why is his name not better known?

Edward Hopper – East-Side Interior – 1922

Things turned out well for just one of the two men who had been friends. Hopper’s work is hymned and shown the world over. Hopper’s former home is museum. His works are listen on Wikipedia. A search for “Edward hopper exhibitions” brings up pages of results on Google. And Lewis? The National Gallery of Australia holds just six of Lewis’s works in its collection. And not a single one is displayed online.

As Messy Nessy notes:

Years later, when Hopper was preparing for a one-man show in Pittsburgh at the height of his career, he rejected the notion that Lewis’ work had influenced his own or that he had studied “under Lewis” as implied by the exhibit’s biographical essay. “Lewis is an old friend of mine,” he countered. “When I decided to etch, he, who had already done some, was glad to give me some tips, on the purely mechanical processes, grounding the place, printing etc”. By this time, the two artists were no longer friends however. According to Edward’s wife Josephine, Lewis and his wife Lucille had given the Hoppers up, “quite understandably. It had been too much of a blow to have E.H so successful.”

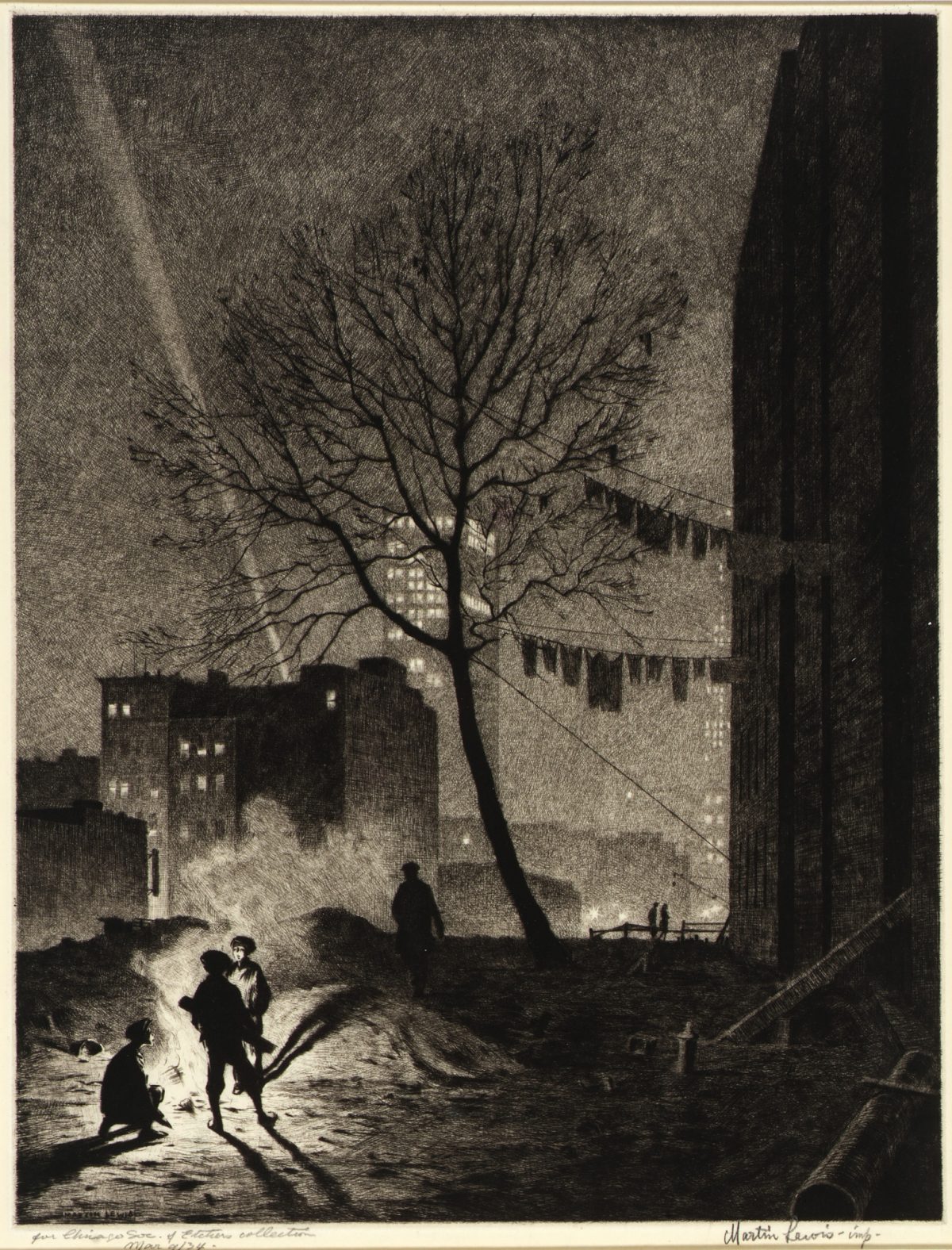

The Glow of the City – 1929 – Martin Lewis

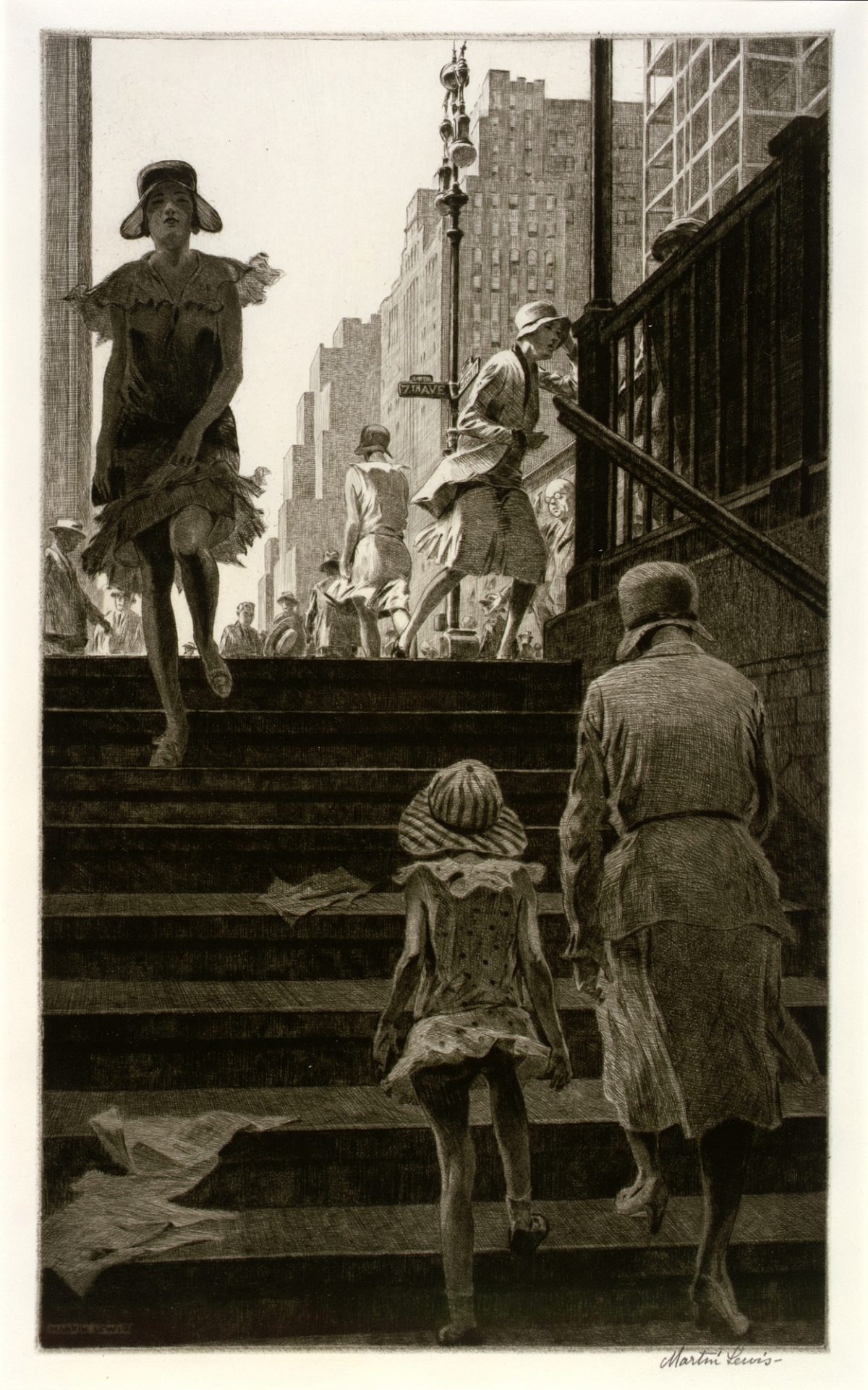

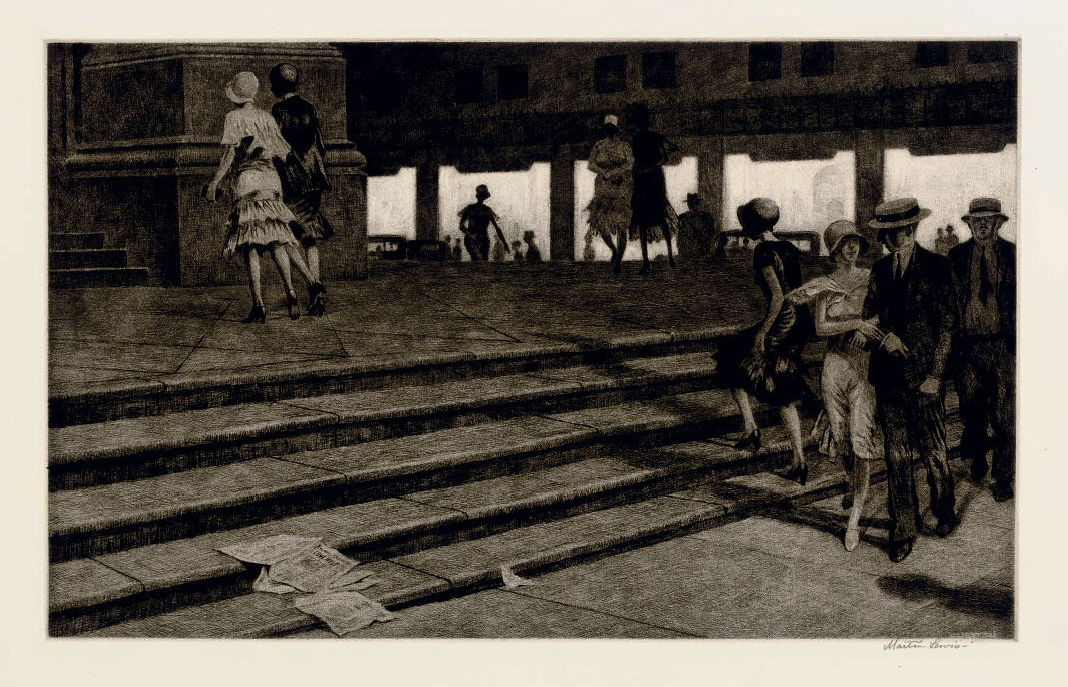

SUBWAY STEPS – Martin Lewis – 1930 – drypoint on paper

In a terrific essay on Martin Lewis, DC Pae tells us how he arrived in the US in 1900 from Castlemaine in the state of Victoria, Australia. San Francisco was his first port of call, where he painted campaign decorations for William McKinley’s 1900 presidential bid.

As the final curtain fell on the glory days of printmaking, a new star of the ‘American Scene’ was in the ascent; the age of Edward Hopper would establish itself in popular consciousness – a shift that was to etch itself upon the psyche of modern art-history in a way that lithography no longer could. If the Crash of 1929 was to have a catastrophic effect on the financial status of the United States, and globally in turn, its denizens plunged into a climate of social deprivation and unease, then the now unlamented casualties of the American art scene were to pay a similarly high price. For by the time of his death in 1962, Martin Lewis was all but forgotten by a world that had once embraced and celebrated the mastery of his craft…

During the onset of the Great Depression in the early 1930s, artists found working in a treacherous financial climate in the already expensive New York City, a lifestyle hard to maintain. This necessitated Lewis’s move, somewhat reluctantly, to Sandy Hook, rural Connecticut in 1932. Here, he concentrated on painting pastoral landscapes in a departure from his previously celebrated urban subject. He also produced small-town drypoint printed scenes. His paintings, expressionist in style and with much greater consideration for nature as predominant, reflected his surroundings, but were not favoured by collectors. He established the School for Printmakers with his contemporary Armin Landeck at George Miller’s lithography studio, both were leading names in the etching world, and Lewis made three.

In 1936, unable to make his mark with his Connecticut scenes, Lewis returned to New York City having retained his friendships and contacts there. There, he found an etching market in a state of collapse, the craft of lithography no longer in demand; he forged ahead for many years but failed to regain the critical success enjoyed at the zenith of his career. He took up a teaching position at the Art Student League in 1944 where he remained until 1951, however poor health forced his retirement in 1952.

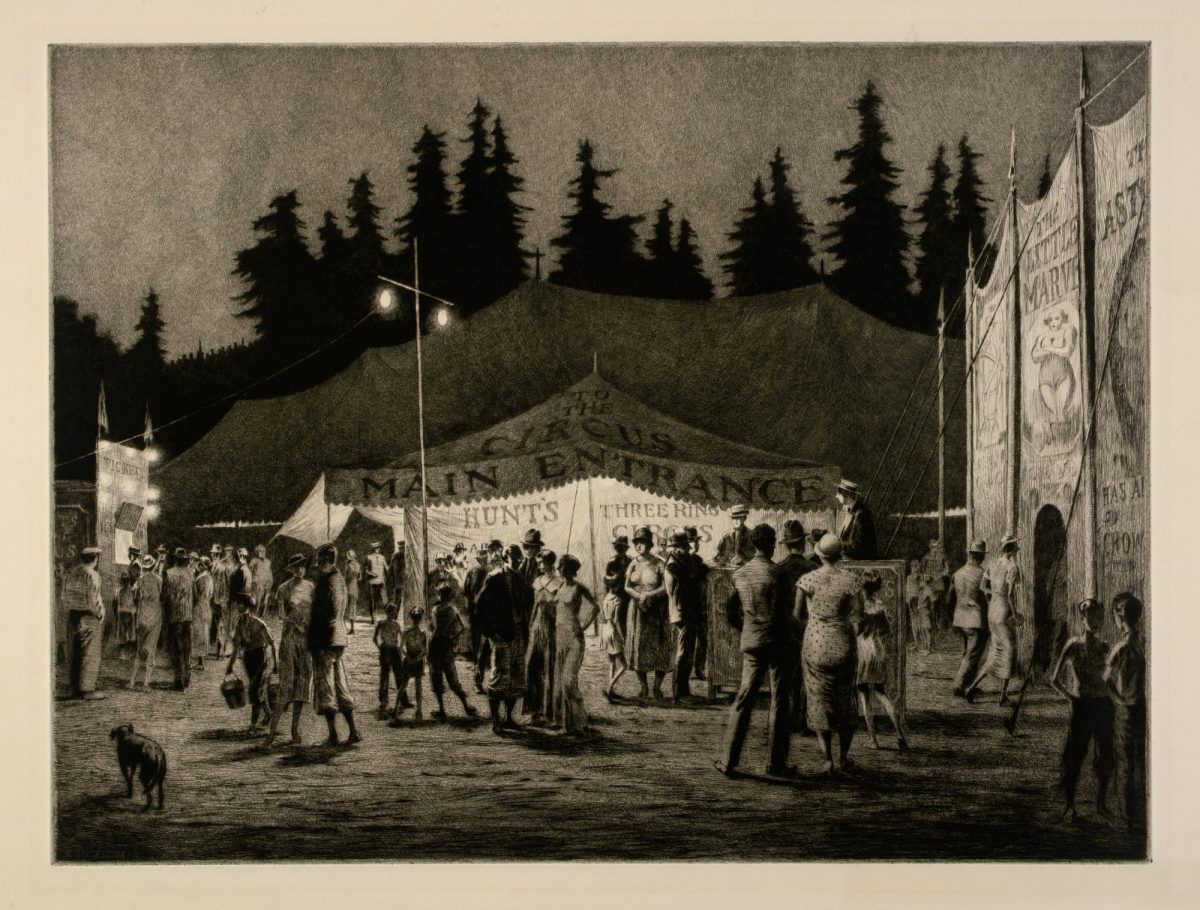

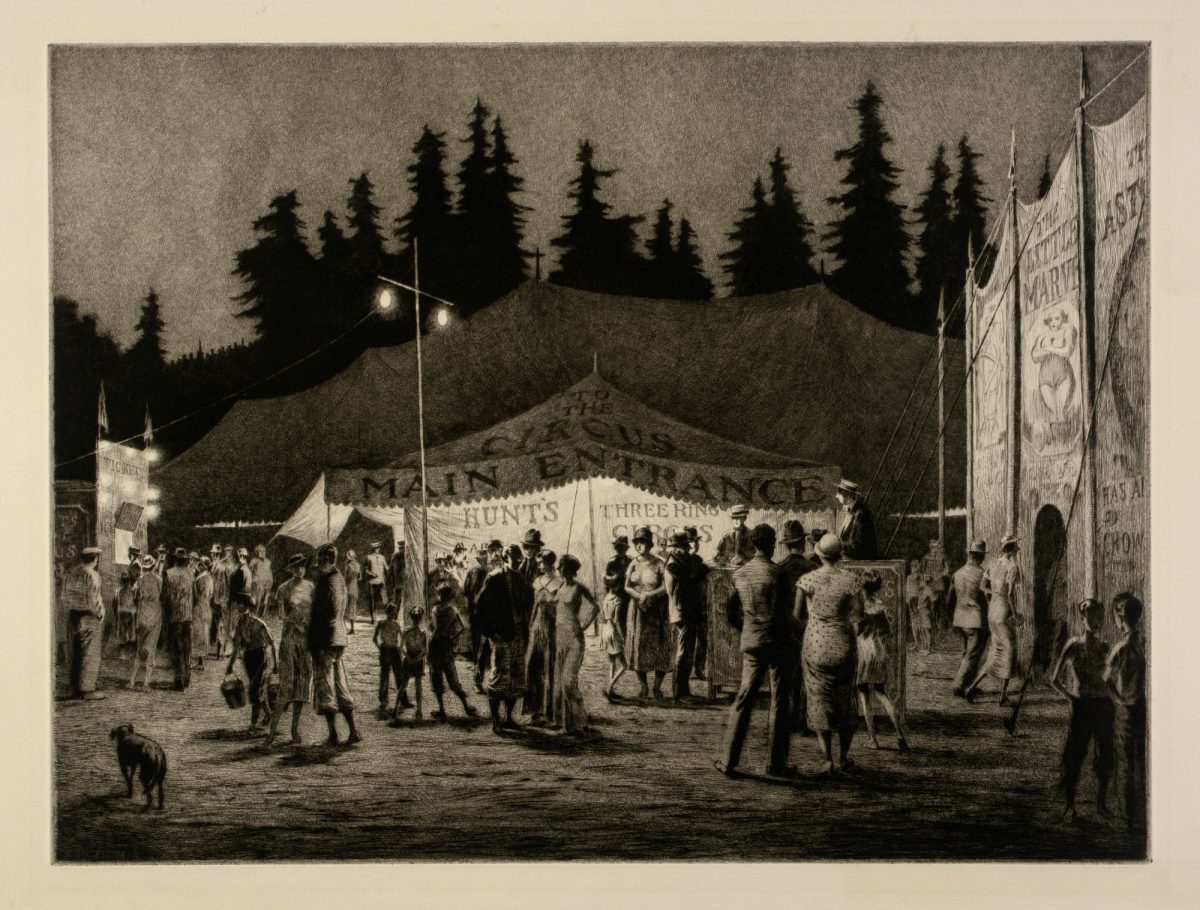

Circus Night, 1933, drypoint and sandpaper ground on paper

Martin Lewis – Late Traveler – 1949

Stoops in Snow

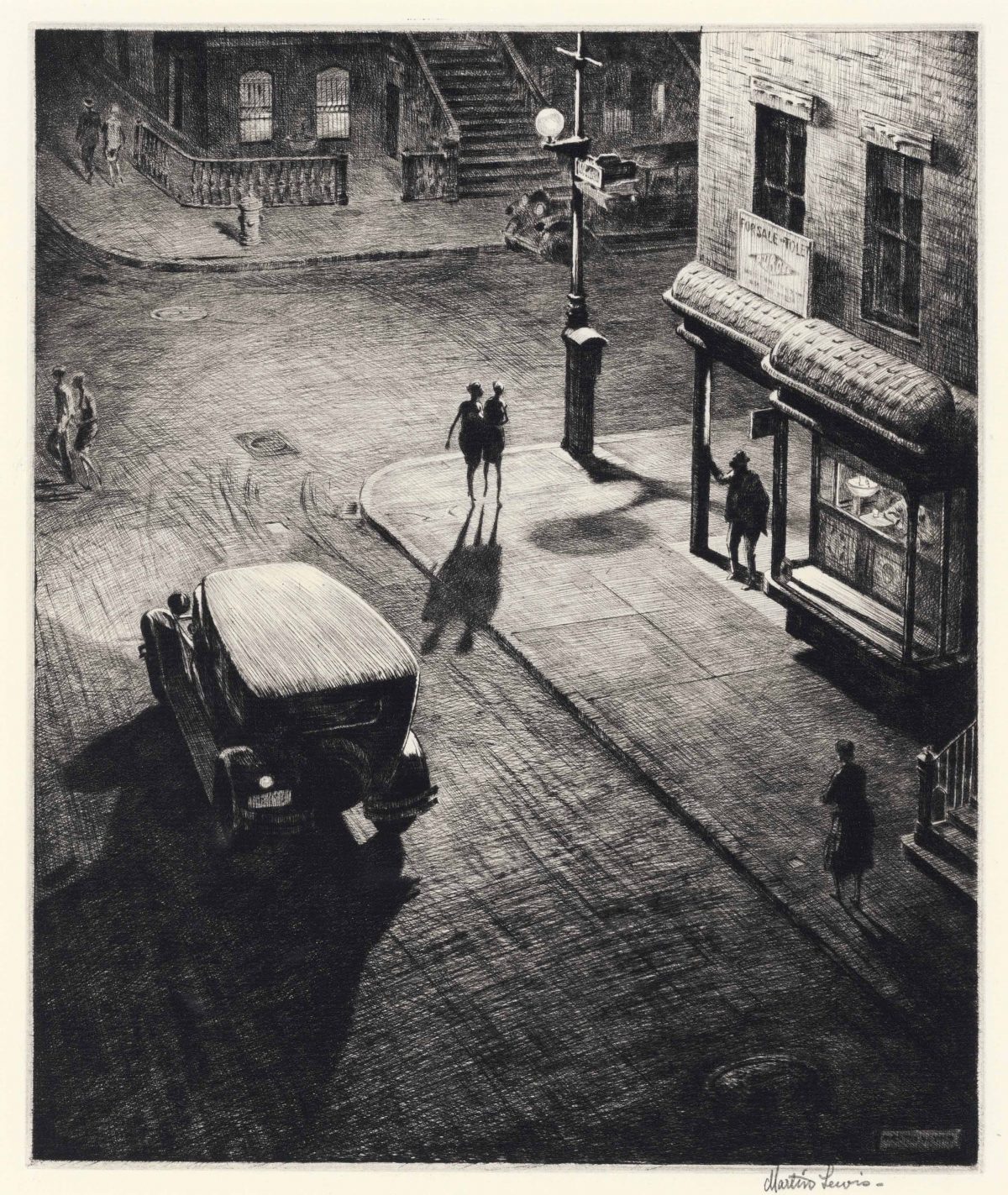

Relics (Speakeasy Corner)

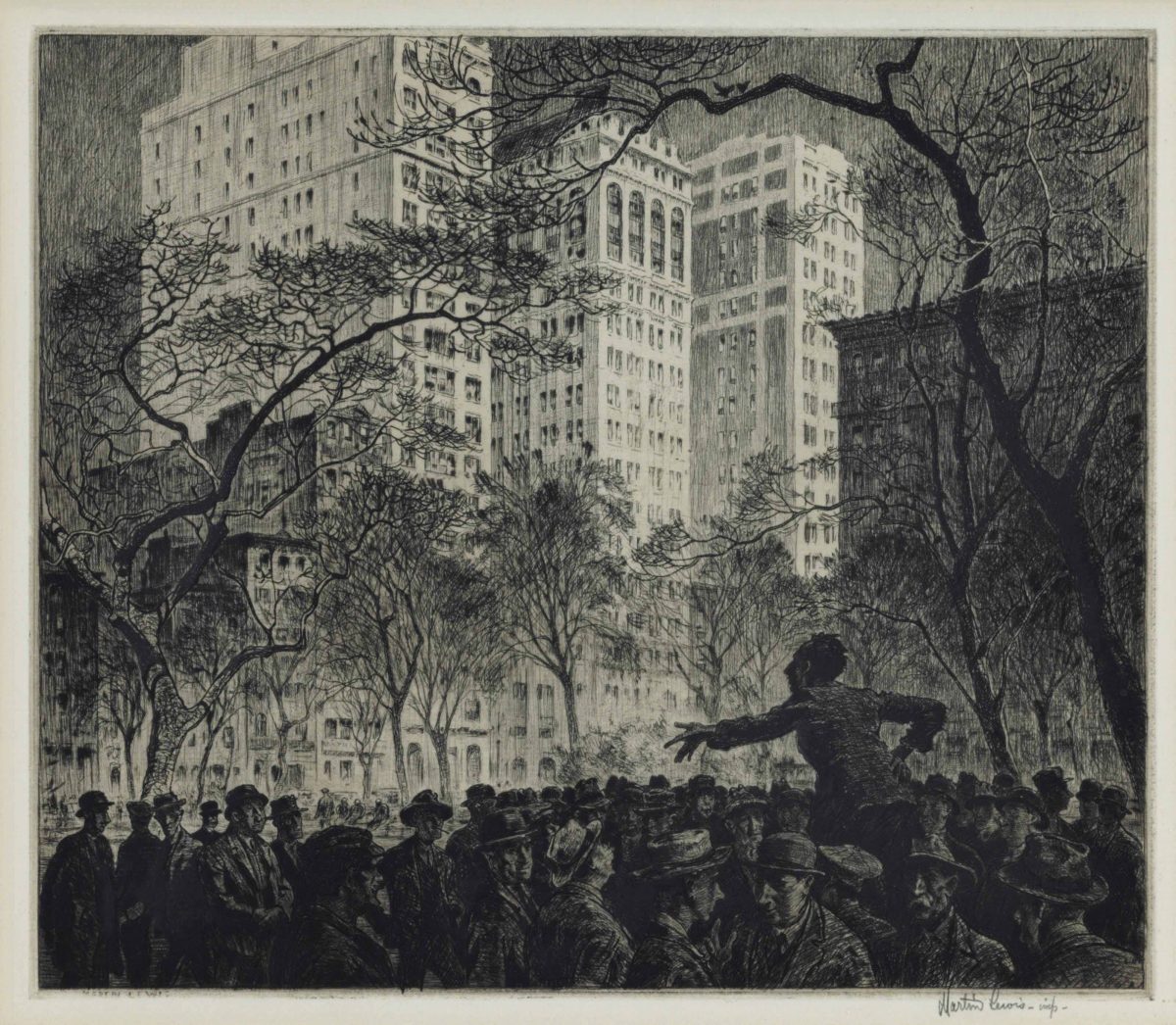

The Orator, Madison Square

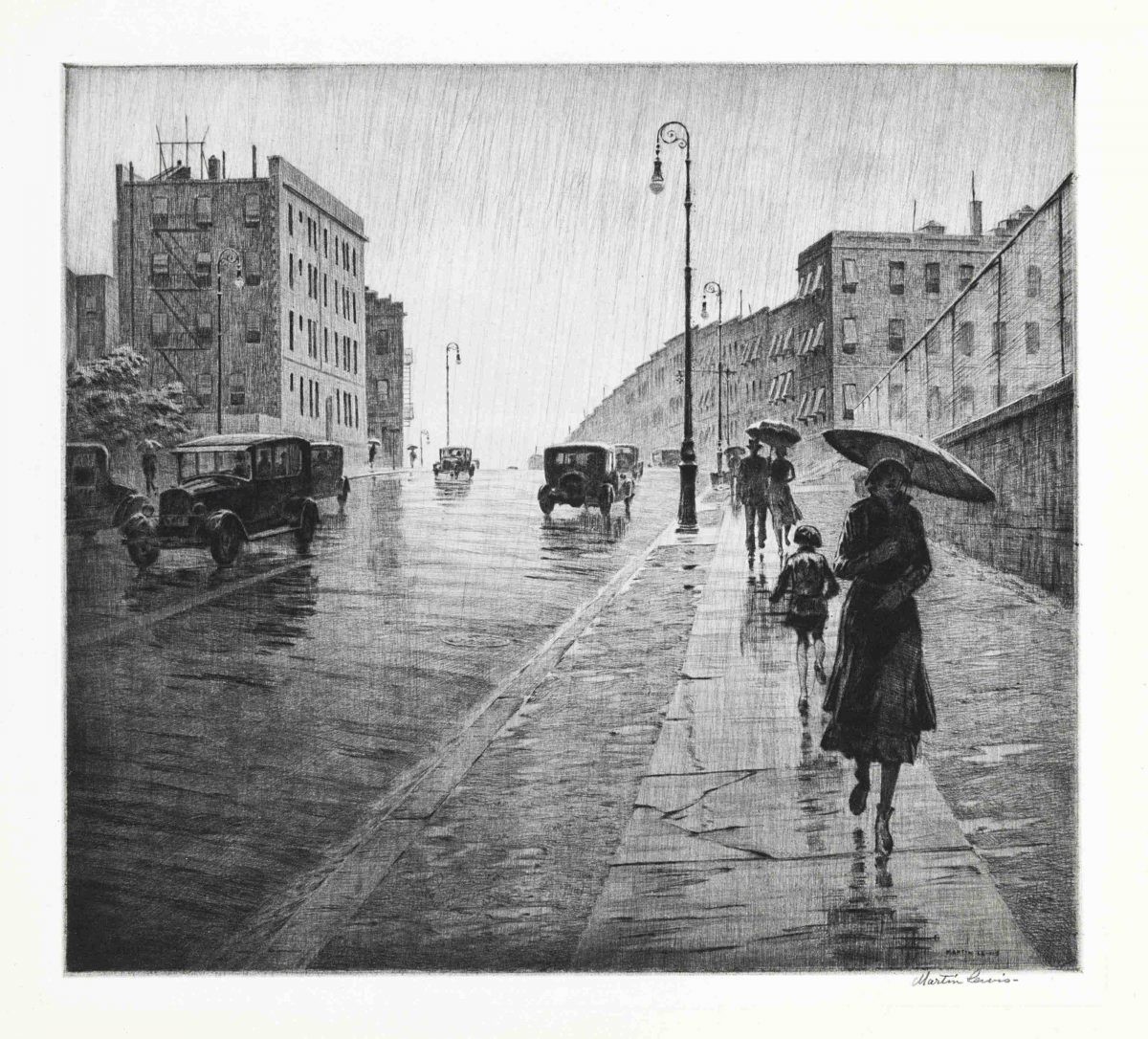

Rainy Day, Queens

Spiral Staircase, Queensboro Bridge

CIRCUS NIGHT – Martin Lewis – 1933 – drypoint and sandpaper ground on paper

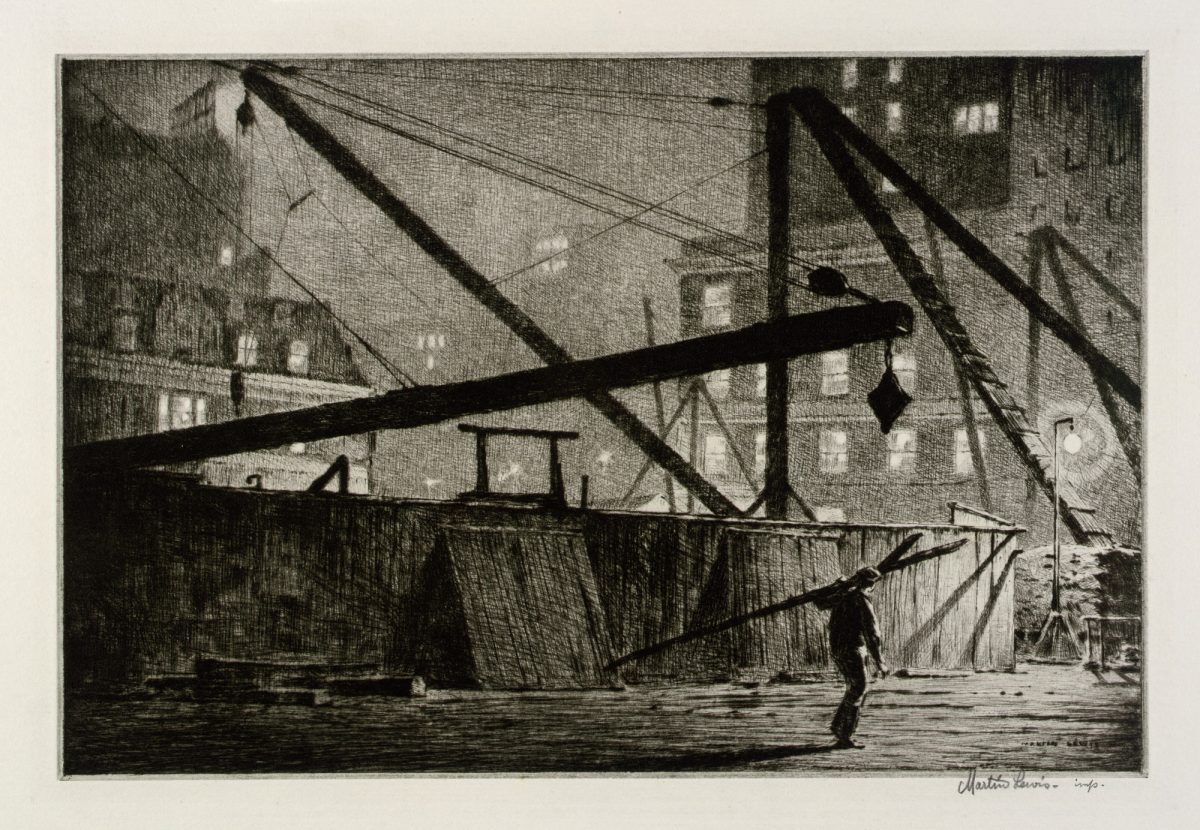

DERRICKS – Martin Lewis – 1927 – drypoint on paper

DOCK WORKERS UNDER THE BROOKLYN BRIDGE

Martin Lewis

ca. 1916-1918, printed 1973

aquatint and etching on paper

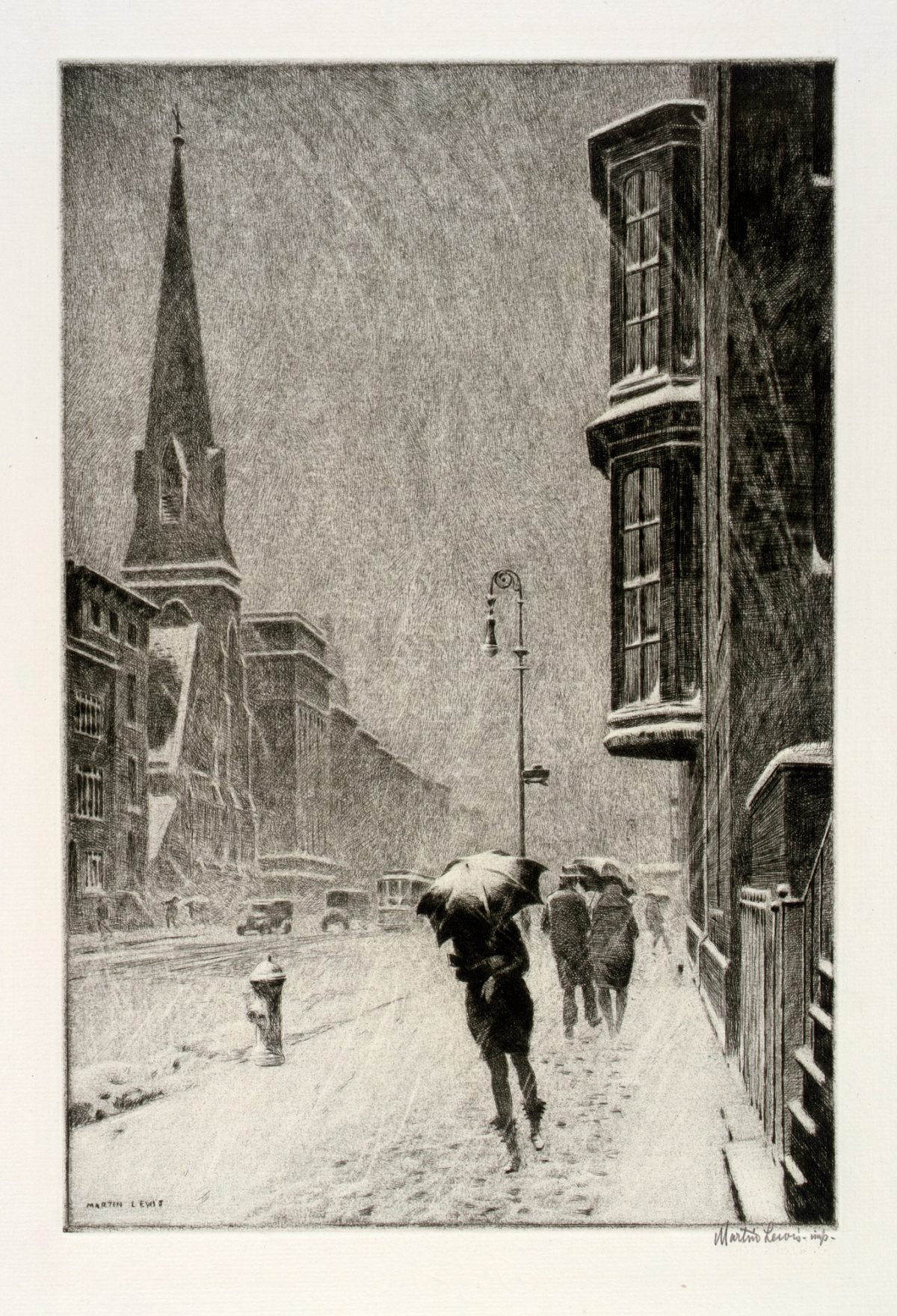

Martin Lewis, Bay Windows (Snowy Day–Lexington Avenue), 1929, drypoint, sandpaper ground, on paper

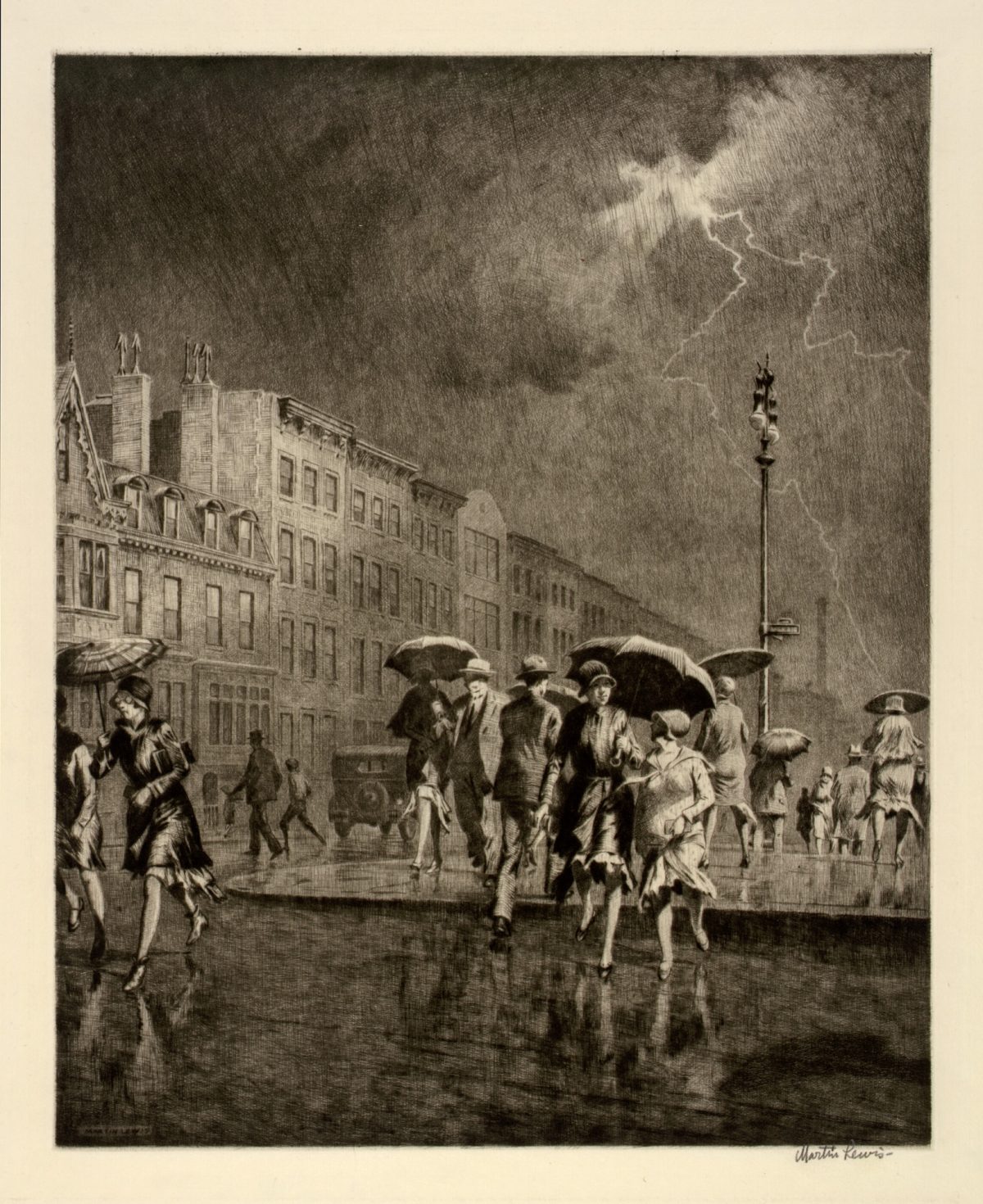

BREAK IN THE THUNDERSTORM – Martin Lewis – 1930 – drypoint on paper

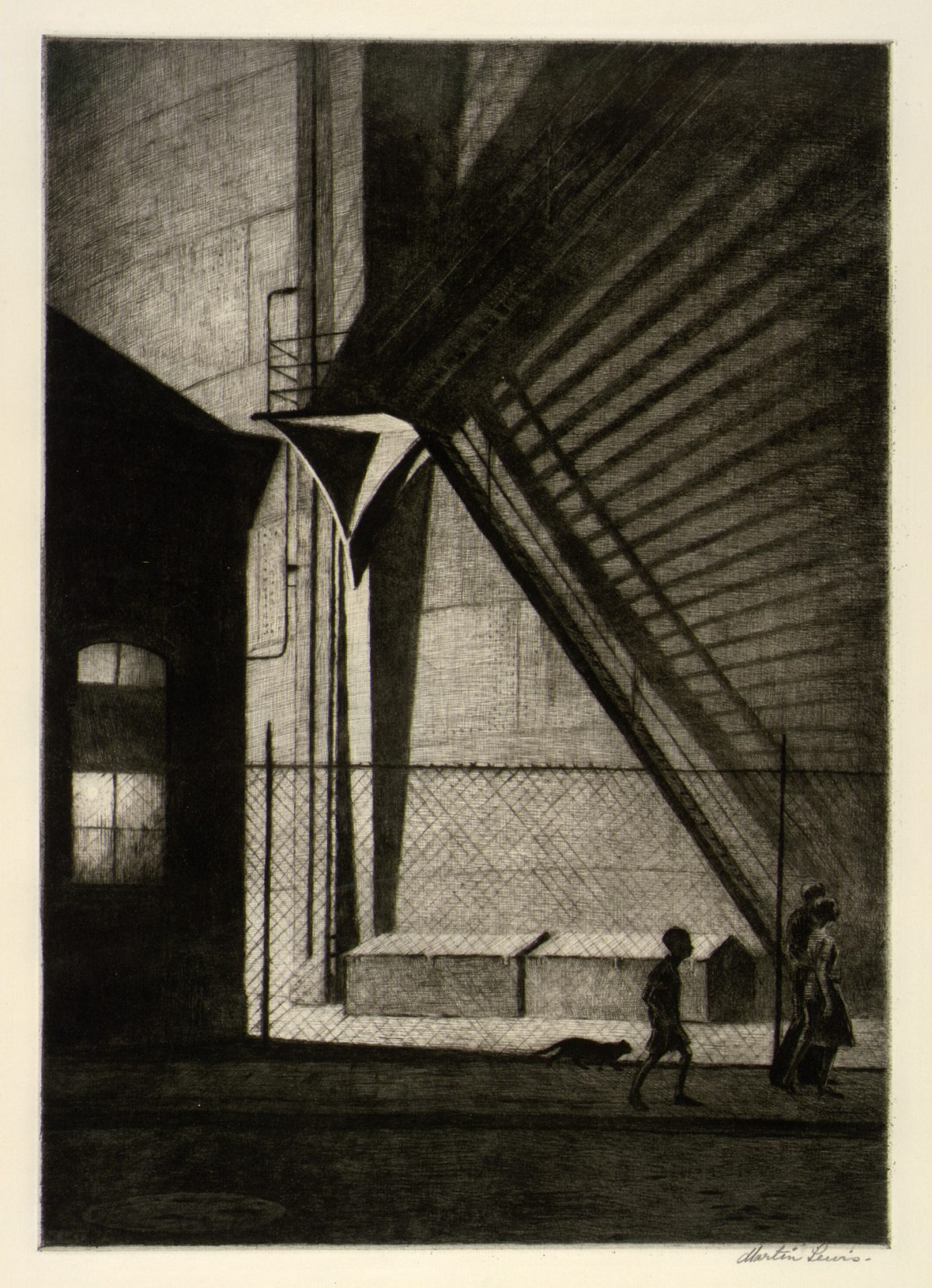

SHADOW MAGIC – Martin Lewis -1939 – drypoint on paper

MARTIN LEWIS – Yorkville Night

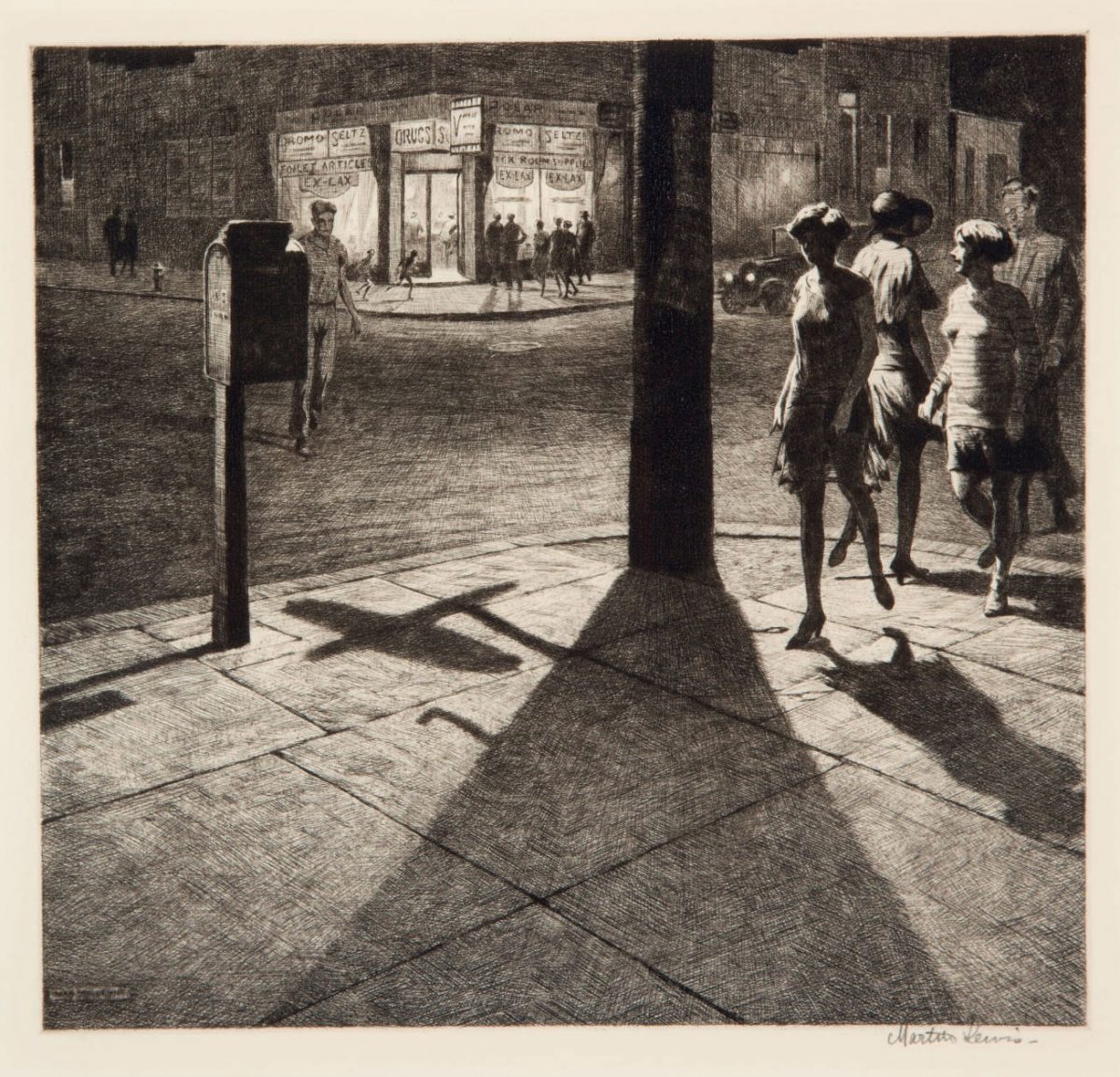

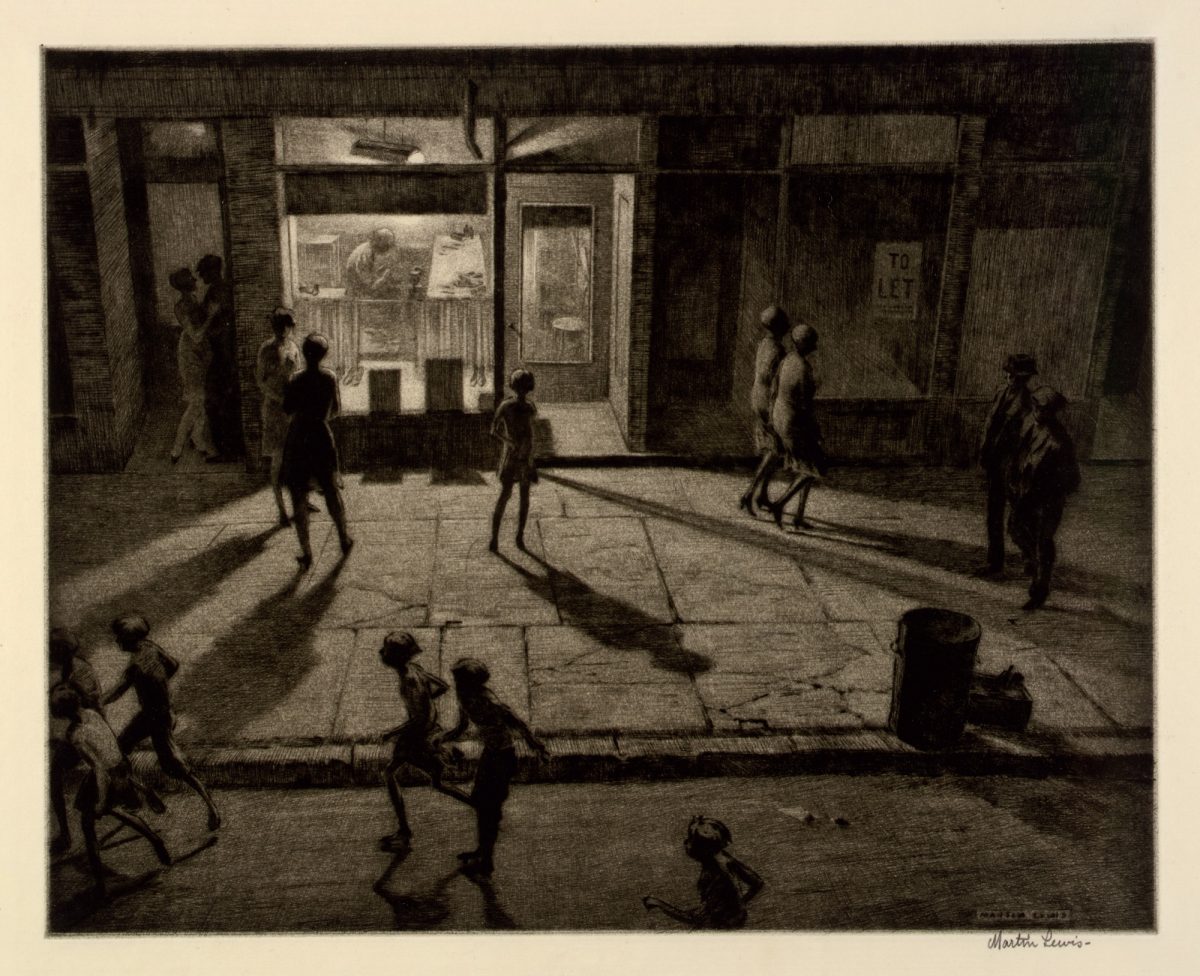

QUARTER OF NINE–SATURDAY’S CHILDREN – Martin Lewis – 1929 – etching on paper

Fifth Avenue Bridge – 1928

TREE, MANHATTAN – Martin Lewis – n.d. – drypoint

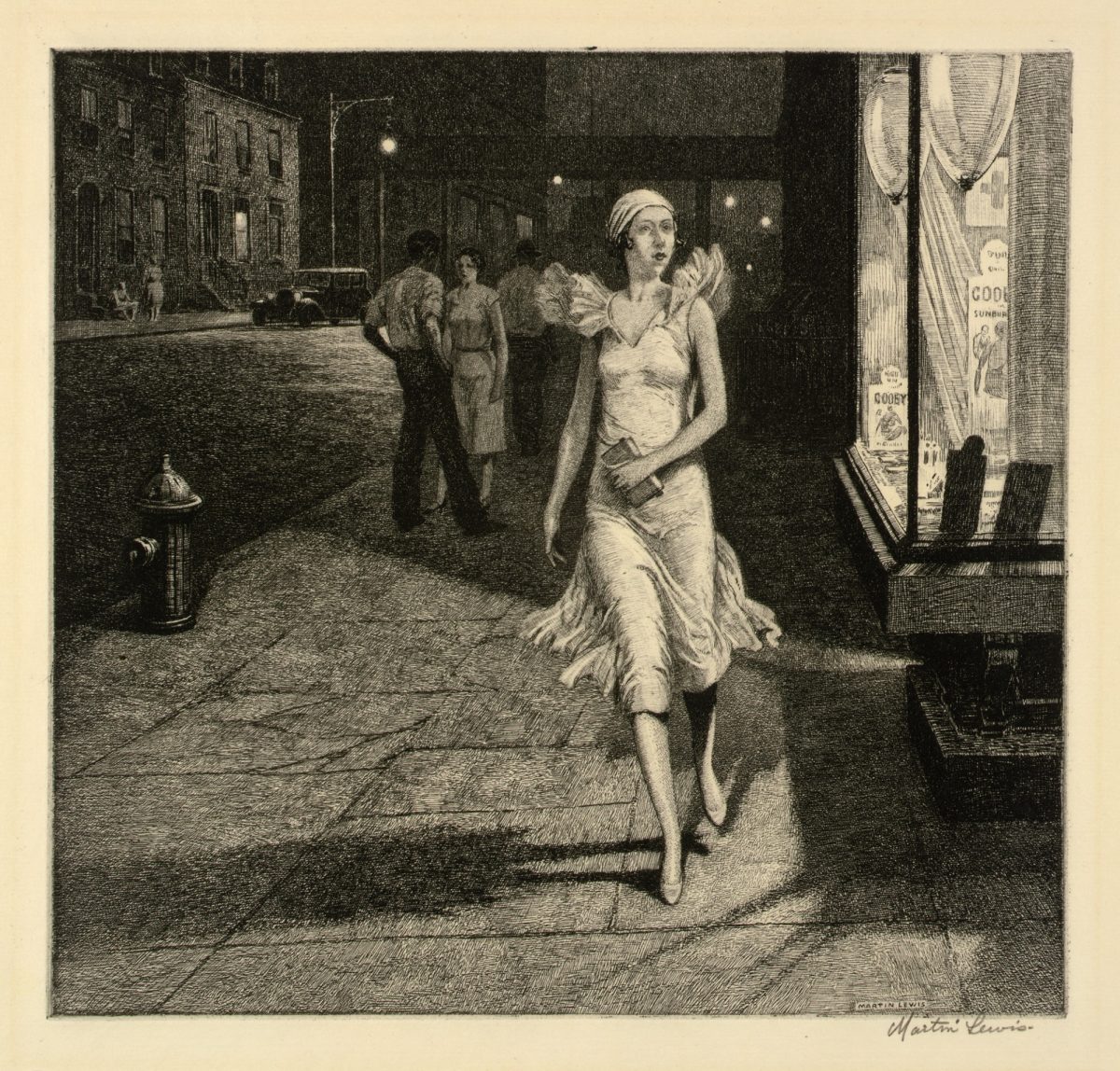

SPRING NIGHT, GREENWICH VILLAGE – Martin Lewis – 1930 – drypoint on paper

M29813-4 001

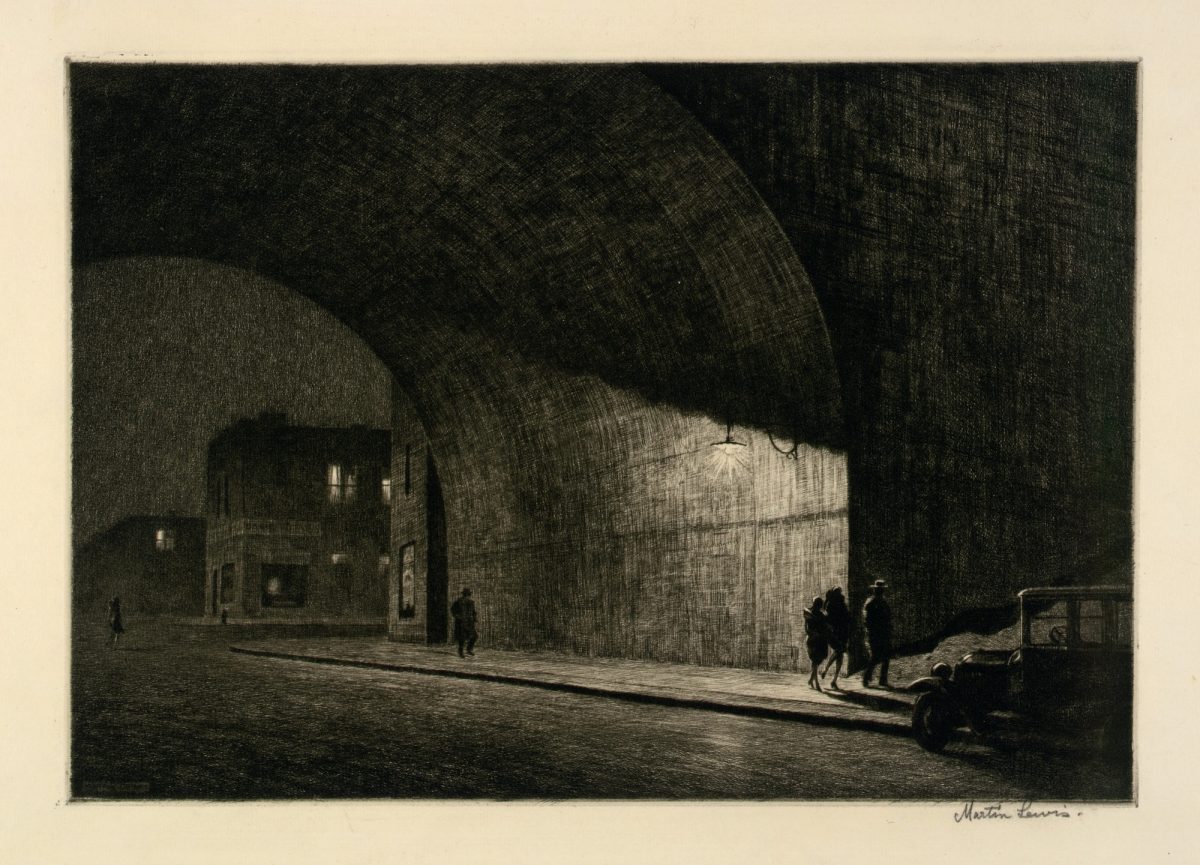

Martin Lewis, Arch, Midnight, 1930

NIGHT IN NEW YORK- Martin Lewis – 1926 – etching on paper

Via: The Smithsonian, ArtBlart

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.