When you’re a film actor, it’s easy to understand how one can obsess over some less than perfect facial or physical feature that is going to be magnified by the camera on the big screen, writes Jeff Stafford. But in most cases these fears are usually unfounded and not even something the average moviegoer would notice or care about. Claudette Colbert and Jean Arthur both insisted on being shot from the left side for profiles; Colbert called the right side of her face “the dark side of the moon”. Fred Astaire used movement and positioning to distract people from what he felt were his unusually large hands and Bing Crosby dealt with his increasing baldness by wearing hats at all times (he refused to wear toupees). Orson Welles’ insecurity over the size of his nose, however, is probably the most baffling of the actor hangups I’ve read about.

There is absolutely nothing wrong with Orson Welles’ nose but the legendary actor/director/producer thought it was too small. He was once quoted as saying “My own nose is nothing” and lamented that it “had not grown one millimetre since infancy”.

In a sketchbook entry from 1955, Welles wrote: “You may have wondered why I look so peculiar on the television. And it’s partly, I must confess to you, the fact that you see my nose as it is. In most of the films that I appear in, I put on a false nose. Usually as large as I can find.” Yet when you look at photos of the young Orson Welles is there something about his nose that seems inadequate? No, it’s only in the mind of Welles that there’s a problem, one that he tried to remedy since his early days in theatre with a variety of fake noses created and employed for every role and character.

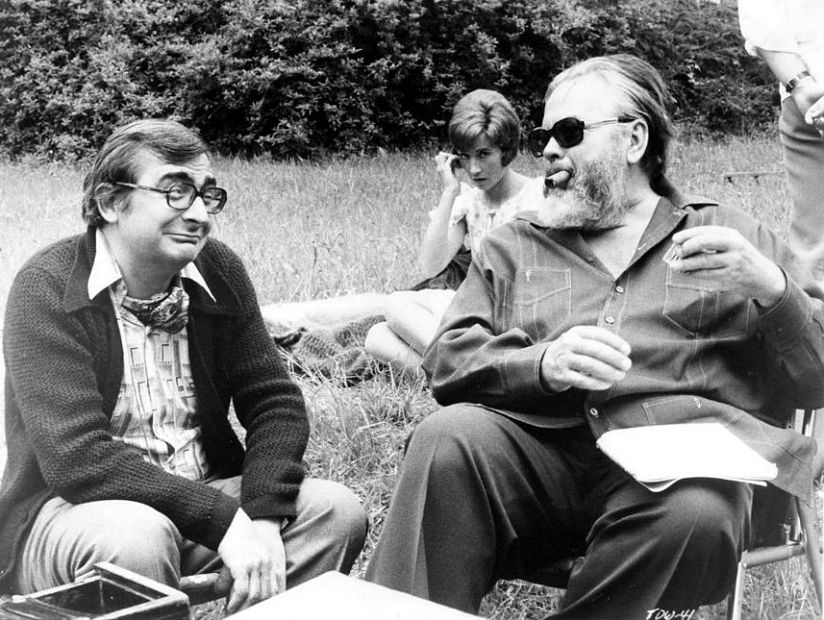

Orson Welles Almost unrecognizable behind his beard and dark glasses, Orson Welles made this appearance in Paris, France, after his arrival from Portugal. His Shakespearean beard is one he grew for the film version of “Othello” which he completed in Morocco. March 14, 1950

It’s quite possible that Welles has never allowed his real nose to be filmed without some additional padding or special makeup except for his youthful scenes in Citizen Kane (1942), his Irish sailor in The Lady from Shanghai and any live appearances as himself. Perhaps he felt it allowed him greater versatility in creating a character. Or maybe he just loved the art of disguise.

One thing is true though as Welles grew older. If you didn’t notice his nose before, you certainly couldn’t avoid staring at it in movies like Touch of Evil or The Long, Hot Summer or Ten Days of Wonder as the noses grew larger and more bulbous.

But did building a bigger, more imposing nose result in a greater performance or improve the quality of his acting in movies like The Tartars (1961) or Ferry to Hong Kong (1959) or Marco The Magnificent (1965)? I think not though Welles would obviously disagree.

Welles’ peculiar focus on this part of his physiognomy has been documented and noted in countless biographies like this detail that appears in Barbara Leaming’s biography on Orson. After completing his 1948 film version of Macbeth, Welles agreed to appear in Black Magic as the title character Cagliostro. “In Rome where he installed himself in grand style at the Excelsior,” Leaming wrote, “Orson seemed far more worried about the supply of false noses he had inadvertently left in Hollywood than about his unfinished picture [Macbeth]. Until he received a package of noses from home he would somehow have to conserve the ones he had.”

Around this same time Leaming mentions that Welles was planning a movie production in Paris of Cyrano de Bergerac for producer Alexander Korda. “Says Orson: We were going to do all the sets where I was shot with big doors and high door knobs, and so on – so I’d look very, very short, because I always thought that Cyrano should look up at everybody.” As for the magnitude of the false nose he would wear in the part, it seemed he would need several different sizes: “I discovered a wonderful thing about Coquelin, who created the part, that nobody knows,” recalls Orson, “which is that in every act his nose got shorter. Isn’t that brilliant? Absolute genius! And so of course I was going to do that.” Unfortunately, the play was never produced; Korda sold the property to Hollywood instead for more money and Jose Ferrer was cast in the film version.

Orson Welles American actor-director Orson Welles plays the blind seer in Sophocles’ “Oedipus the King,” which is being filmed in the ancient Dodoni Theater in northwestern Greece – 1967

On the web site Shadowplay there is a fascinating anecdote by David Cairns about Welles’ nose collection: “Each new snout would be hand-crafted by studio artists to the actor’s exacting specifications, and at the end of filming would go into Welles’ private collection. Each nose therein had its own display case and its own name, although the names did not correspond to the names of the characters the noses were designed for. Sheriff Hank Quinlan’s bloated drunkard’s schnozz was named Sandra, for instance. The aquiline hooter worn in his television King Lear, made by cutting the corner from a shoebox, went by the nickname Sloane Jnr. On social evenings, Welles would perform magic tricks with the noses, making them vanish, or performing a variation on the old shell game, using three noses and a garden pea.”

If you could hold a séance and conjure up and interview all of the deceased actors, directors, crew people and makeup artists who worked with Welles and had stories about his fake noses, you’d probably end up with a book as detailed and as massive as Tim Lucas’s exhaustive biography on director Mario Bava. I’ve culled just a tiny fraction of them below from various sources.

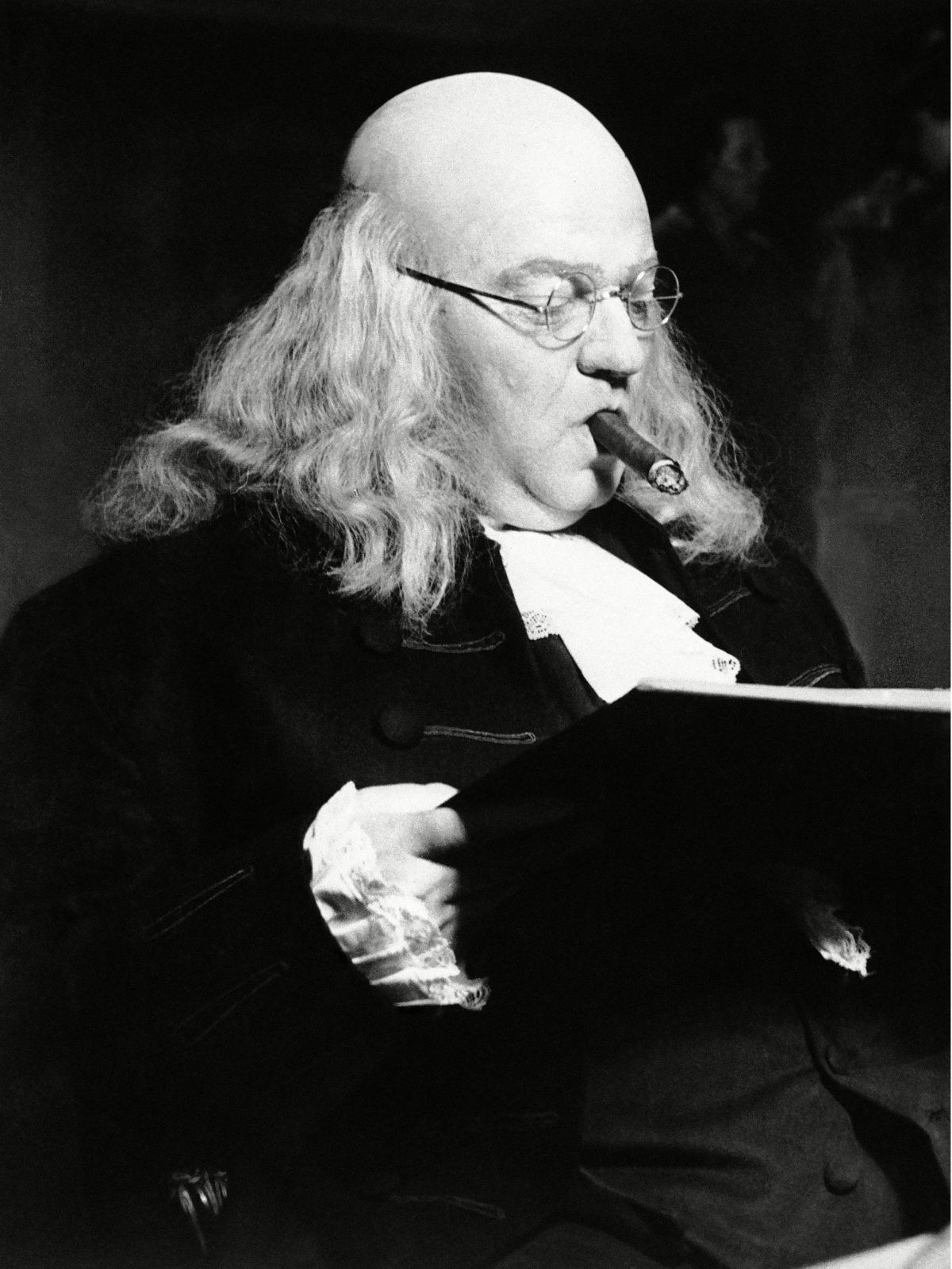

Orson Welles smokes a cigar and reads his role of Benjamin Franklin between scenes of the historical film “La Fayette” being made at Nice, France. March 12 1961

On the Bright Lights Film Journal site, Peter Tonguette conducted an interview with Juan Luis Bunuel (son of director Luis Bunuel) about the making of the never completed Don Quixote in 1955. Juan worked as an assistant director on the film and discovered quite a few things about Welles’ working methods such as incorporating a limp into his character’s walk (the result of an injury on the set). “Another thing that I found out was that Welles hated his nose. Whenever he can in films, he puts on these huge noses. He was a very big man with this tiny pug nose. And he hated it. In the film you don’t see it much, but he would change the shape of his nose. The make-up lady would come and say, ‘Welles’s nose is a little too green today.’ So I said, ‘Orson, your nose is green!’ ‘Oh, well.’ And then he’d put some more make-up on it. Or it could be twisted the wrong way and I’d say, ‘Orson, your nose,” and he’d push it over into shape. Every day we had to watch out for his nose!”

Just a few years later, Welles was hired to play the Southern patriarch Will Varner in The Long, Hot Summer (1957), an adaptation of William Faulkner’s The Hamlet and some of his short stories. It was not a happy experience for the overweight actor according to a behind the scenes story on AMCTV. Co-star Angela Lansbury recalled: “He was very, very heavy… We were working under dreadful conditions of heat and he was perspiring and he seemed to have a lot of thick make-up on.” It was filmed on location in Louisiana and the rising temperatures played havoc with Welles’ prosthetic nose. Paul Newman, who was witness to the incident, noted: “There’s nothing worse than having someone start a scene and then the make up guy comes over and starts picking and gluing your nose back on.”

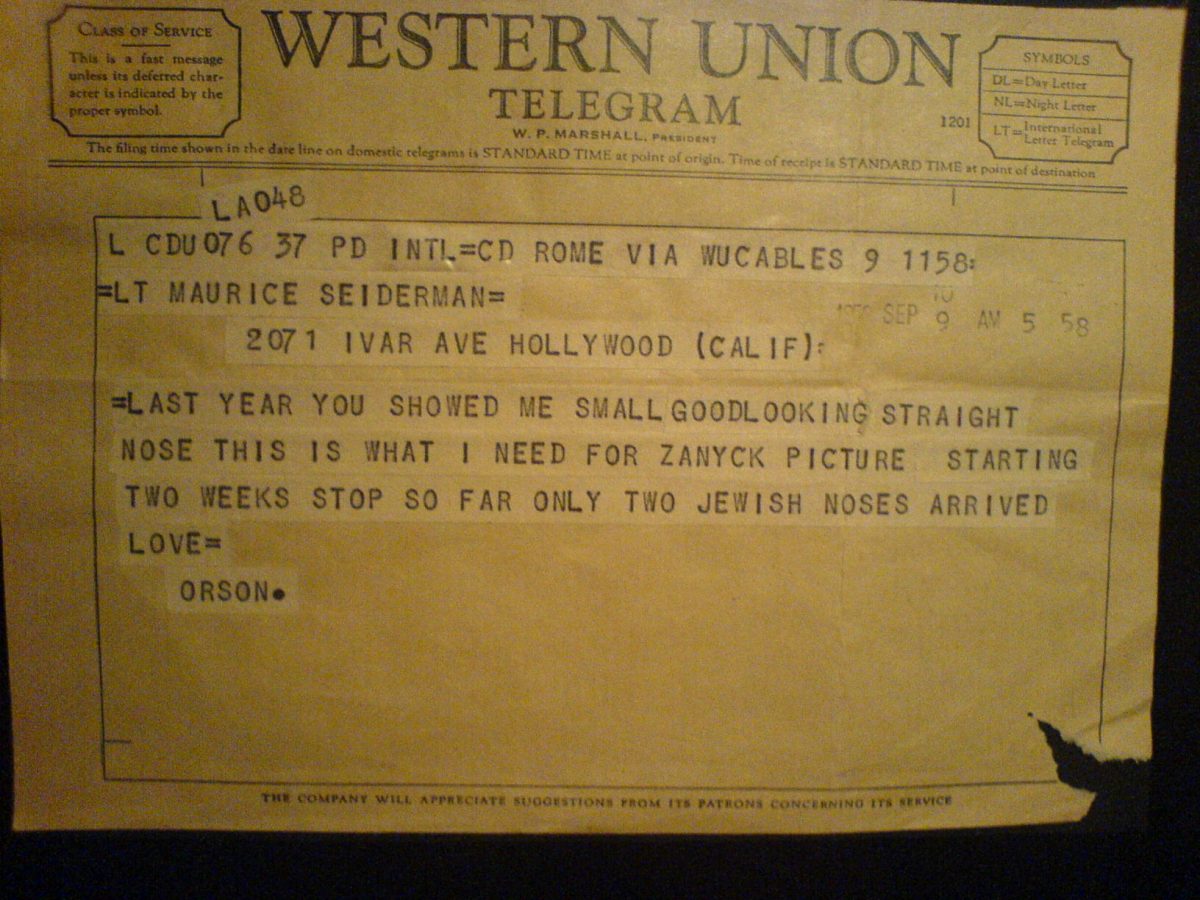

Regardless of the role, there were always plenty of possibilities for the character’s nose as evidenced by this telegram from Welles to Maurice Seiderman, the virtuoso makeup artist who transformed Welles into Citizen Kane, Raymond Massey into Abe Lincoln in Illinois and Alan Carney into a pop-eyed walking dead in Zombies on Broadway. From the date and reference to Darryl Zanuck (incorrectly spelled Zanyck), I suspect that the picture in question is The Roots of Heaven.

One of my favorite stories about Welles’s nose obsession comes from Lewis Gilbert (Alfie), who directed him in Ferry To Hong Kong. (The following excerpt appeared in an article entitled “The Night Orson Welles Lost His Nose in China” on the official web site of the Daily and Sunday Express). Gilbert recalled:

“When I met him, I said that we would begin with a test, which we would shoot the next day. ‘A test? What for?’ said Orson, ‘I don’t do tests.’ ‘A make-up test,’ I said, ‘That’s all, just so the make-up man can settle on what he’s going to do.’ ‘No, that’s not for me,’ said Orson. ‘I have one problem with my face – my nose. It’s too small and I always fix that myself.’ ‘How?’ I asked. ‘It’s all arranged,’ said Orson. ‘I had a parcel sent ahead specially. Everything for making a false nose is in it.’ ‘So it’s here, then?’ I said.

“That night, 20 people scoured every post office in Hong Kong. On this big picture with all its huge logistical problems, top of the agenda was the search for Orson’s nose. Only after a very long time did someone find the missing parcel in one of the post offices. It was brought to us early the next morning. ‘Now all we have to do,’ I said, ‘is hand this to the make-up man and we can get on with the test.’ ‘But I shall be putting the nose on myself,’ said Orson, ‘there’s no need for a test.’

‘And that is what happened. He put the nose on himself every day. Only when scenes were cut together did we find out what we had let ourselves in for. Some shots had the nose tilting upwards; others had it tilting downwards. Occasionally it went sideways and in one shot it was suddenly big and hooked. In the meantime, on set, Orson was still finding ways to play up. He decided that having applied the false nose he would now stuff his cheeks with cotton wool. As a result he was unable to talk properly and produced the most extraordinary sound.’

The truth is that most directors yielded to Welles’ makeup specifications and preparations for his roles despite their better judgment. A perfect case in point is Ten Days Wonder. French director Claude Chabrol, whose 1971 adaptation of a novel by Ellery Queen (a pseudonym and fictional hero for two writers, Frederic Dannay & Manfred Lee) is often referenced as the worst case scenario of Welles’ fake nose addiction. According to Joseph McBride in his biography, What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?: “Chabrol led Welles wear the most outrageously phony nose of his entire career, a ghastly gray-green creation that changes color from shot to shot. One of the film’s detractors said the only suspense was in waiting to see if Welles’s nose would fall of on camera. Admitting that the nose was rather weird, Chabrol told me that there wasn’t much he could do about it: “I asked Orson to change the nose one day, because it was too green, and he said, ‘My dear Claude, I am a changing character – at the end of the film my whole face will be green.’ What can you say?”

If directors were driven to the breaking point by Welles’ insistence on applying his own makeup, most actors were in awe of him and considered him an expert in these matters. In preparing for her “double role” in Billy Wilder’s Witness for the Prosecution in 1957, Marlene Dietrich recalled the challenges facing her in the role and sought Welles’ advice (as recounted in her autobiography Marlene Dietrich: My Life):

“I was enthusiastic at the prospect of playing this role. Naturally, the presentation of ‘the other woman’ made me uneasy, and I took all conceivable pains to transform myself into a person who would be as different as possible from the person I really was. Since the film would stand or fall on this transformation, I made the most extraordinary efforts to become an ugly, ordinary woman who succeeds in leading one of the greatest lawyers by the nose. Despite my many attempts I was not satisfied. I applied make-up to my nose, made it broader with massages, and called on Orson Welles – the great nose specialist – for help. In the long shot in which I’m seen going along a railroad track, I have cushions around my hips and legs. l wrapped pieces of paper around my fingers to make them look as though they were deformed by arthritis. And to complete the picture I painted my nails with a dark lacquer. Billy Wilder made no comment; like all great directors he gave his performers a free hand in the matter of costumes.”

If you’ve seen Dietrich in Witness for the Prosecution, you know that her disguise was a brilliant tour de force and no doubt Welles was an invaluable makeup consultant. The two of them would team up for more adventures in makeup the following year in Touch of Evil.

Jeff Stafford wites at Film Struck h

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.