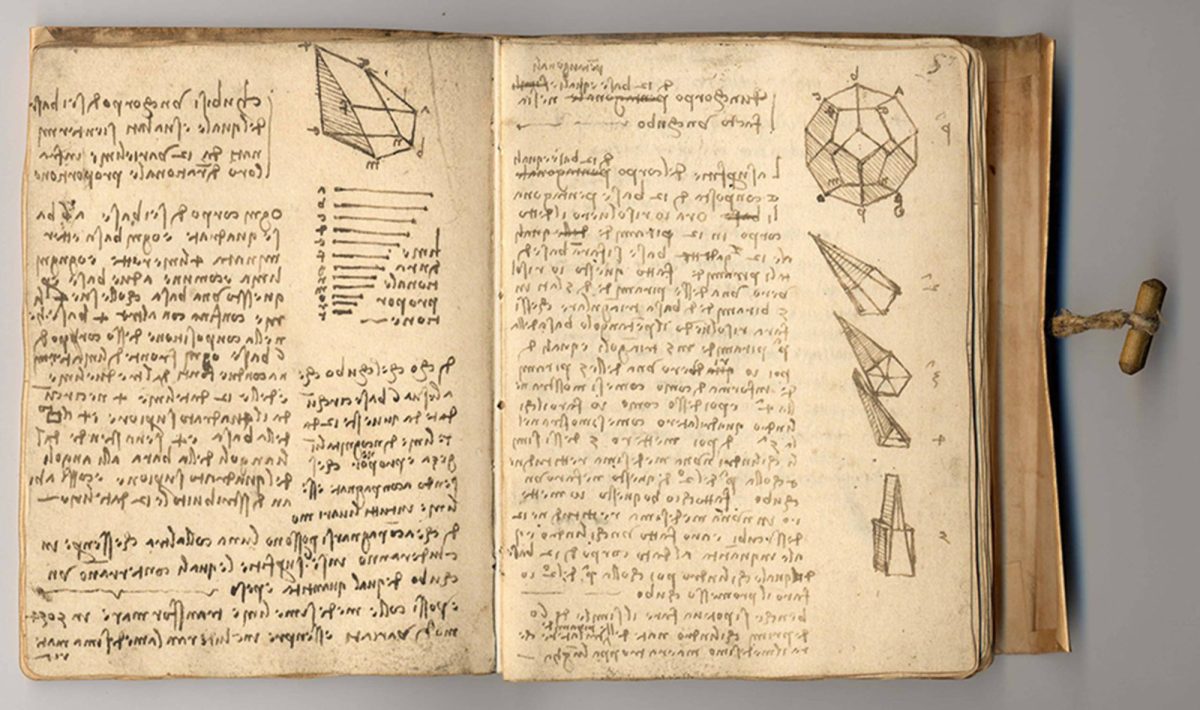

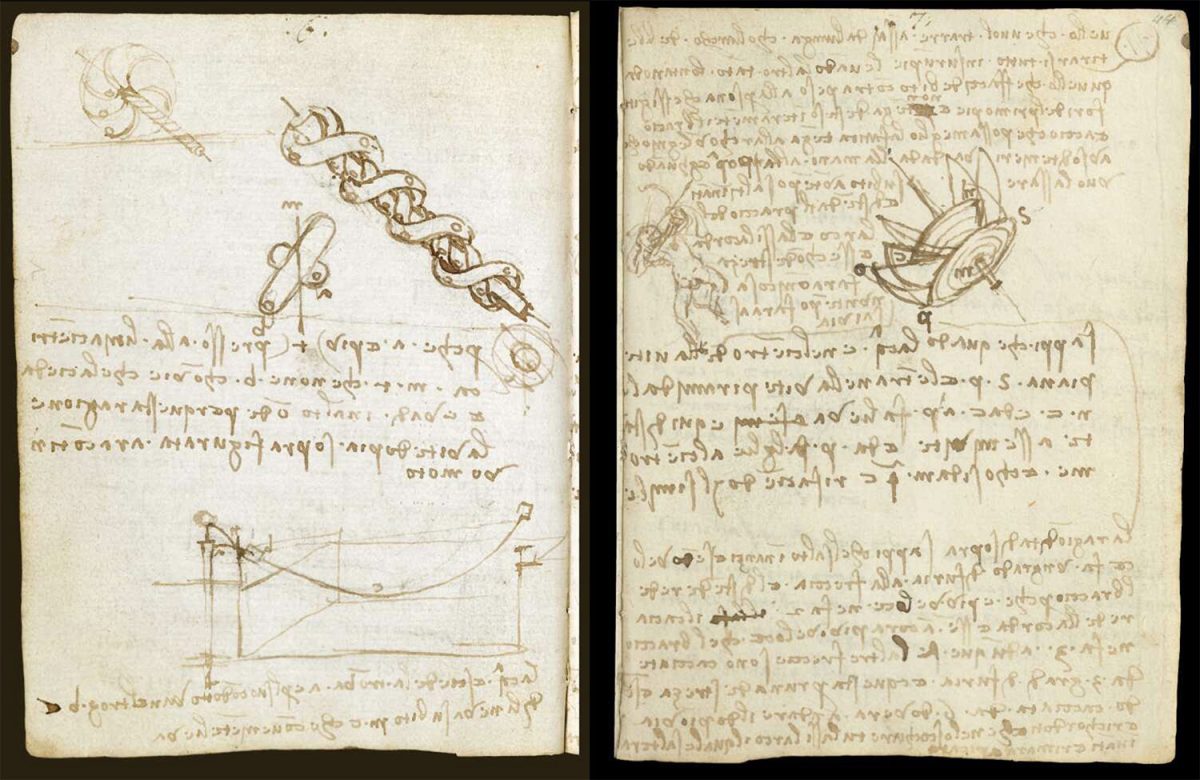

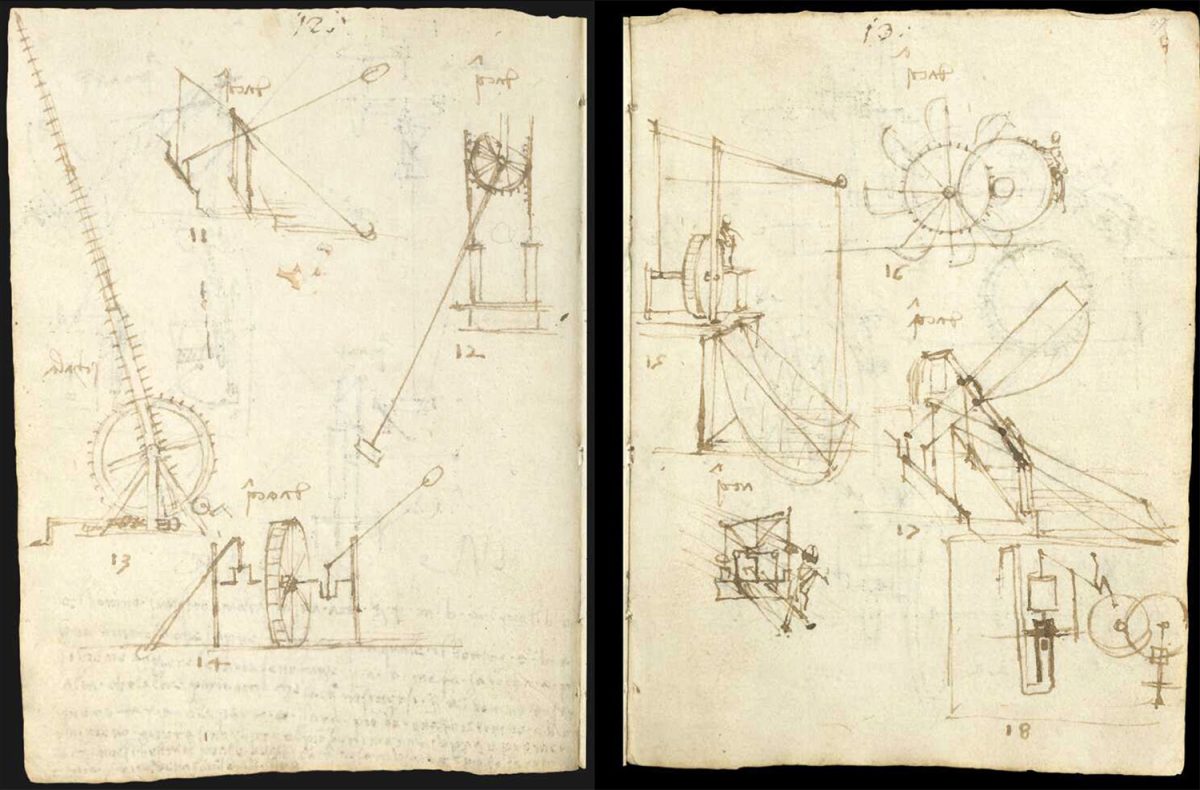

Leonardo Da Vinci (15 April 1452 – 2 May 1519) loved to watch the world go by, to “constantly observe, note, and consider”. To help remember what he saw, the artist and visionary kept a notebook with him at all times. “It is useful,” he said to use the book to write down and sketch things that interested him. Da Vinci’s notebooks give us similar insight into his mind. For instance, we know of his preference for pink tights because in a notebook, he made an inventory of his clothes.

One of his notebooks from 1490 includes a to-do list. NPR had it translated;

[Calculate] the measurement of Milan and Suburbs

[Find] a book that treats of Milan and its churches, which is to be had at the stationer’s on the way to Cordusio

[Discover] the measurement of Corte Vecchio (the courtyard in the duke’s palace).

[Discover] the measurement of the castello (the duke’s palace itself)

Get the master of arithmetic to show you how to square a triangle.

Get Messer Fazio (a professor of medicine and law in Pavia) to show you about proportion.

Get the Brera Friar (at the Benedictine Monastery to Milan) to show you De Ponderibus (a medieval text on mechanics)

[Talk to] Giannino, the Bombardier, re. the means by which the tower of Ferrara is walled without loopholes (no one really knows what Da Vinci meant by this)

Ask Benedetto Potinari (A Florentine Merchant) by what means they go on ice in Flanders

Draw Milan

Ask Maestro Antonio how mortars are positioned on bastions by day or night.

[Examine] the Crossbow of Mastro Giannetto

Find a master of hydraulics and get him to tell you how to repair a lock, canal and mill in the Lombard manner

[Ask about] the measurement of the sun promised me by Maestro Giovanni Francese

Try to get Vitolone (the medieval author of a text on optics), which is in the Library at Pavia, which deals with the mathematic.

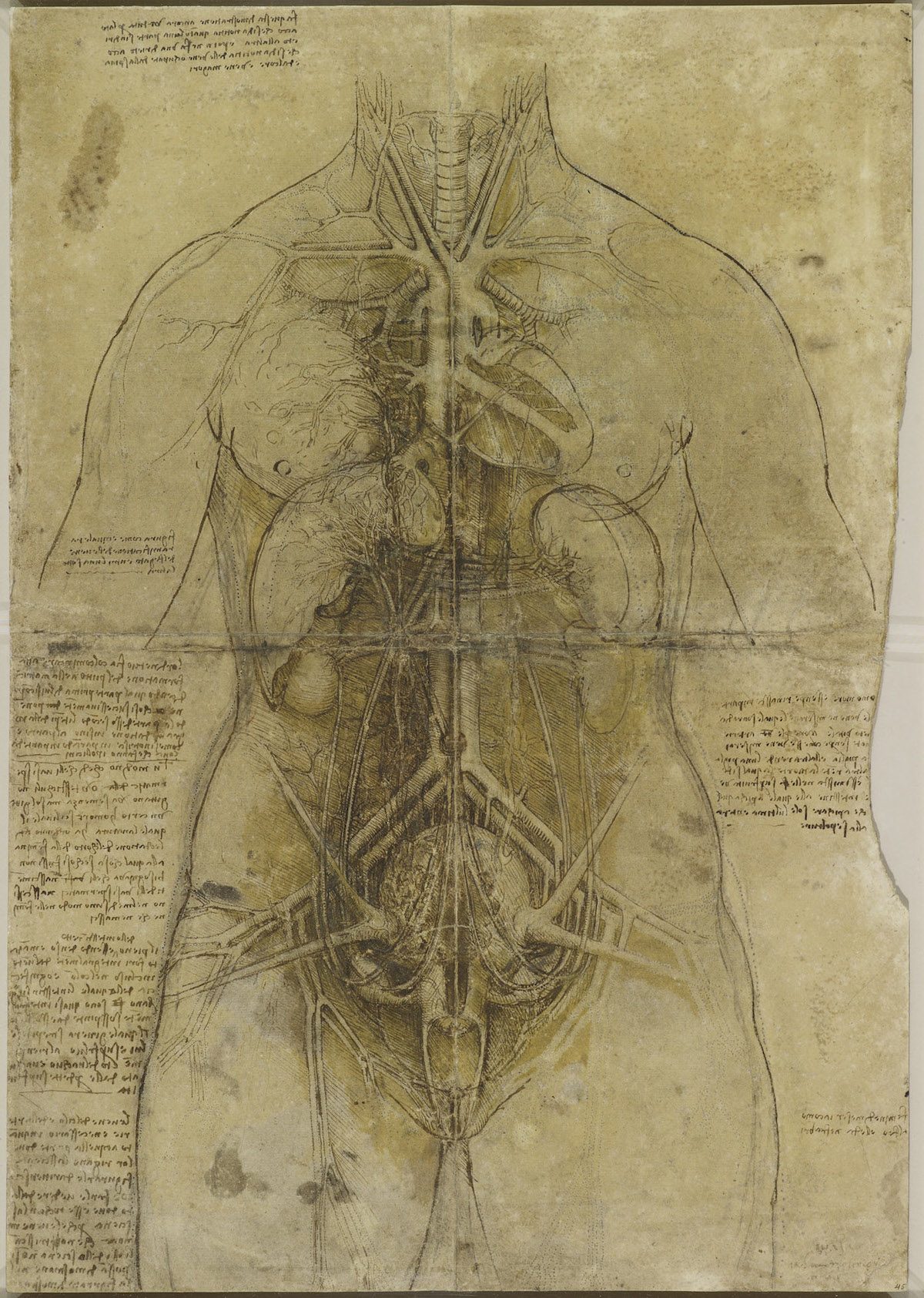

In another to do list written by the Renaissance artist around 1510 before a trip to Pavia, south of Milan, to dissect corpses and draw his bodymaps, he reminds himself to pack “a pane of glass, forceps and a fine-tooth bone saw”. He also shares his thoughts on what it takes to be an anatomist:

“On the Utilities. Spectacles with case, firestick, fork, bistoury [a surgical knife], charcoal, boards, sheets of paper, chalk, white wax, forceps, pane of glass, fine-tooth bone saw, scalpel, inkhorn, penknife.

“Get hold of a skull. Nutmeg.

“Observe the holes in the substance of the brain, where there are more of less of them.

“Describe the tongue of the woodpecker and jaw of a crocodile.

“Give measurement of the dead using his finger [as a unit].

“Get your books on anatomy bound. Boots, stockings, comb, towel, shirts, shoelaces, penknife, pens, a skin for the chest, gloves, wrapping paper, charcoal.”

Glimpses of the gruesome nature of his trip, are revealed in the notes, such as a reminder “to break the jaw from the side so that you can see the uvula in its position”.

There are also some word for budding anatomists:

“Though you may have a love of such things, you will perhaps be impeded by your stomach; and if this does not impede you, you will perhaps be impeded by the fear of living through the night hours in the company of quartered and flayed corpses.”

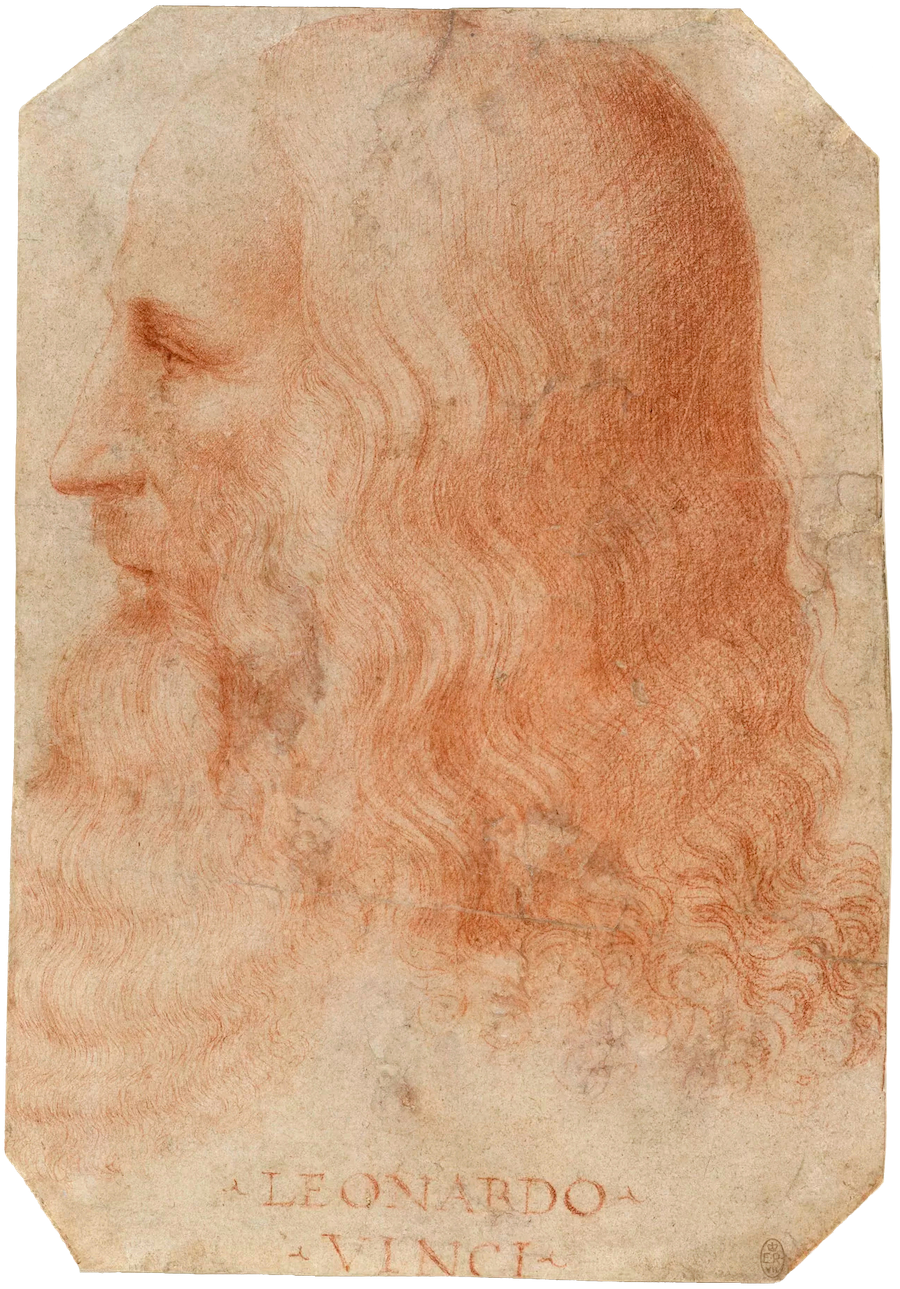

Francesco Melzi – Portrait of Leonardo.png

Created: circa 1515–1517

Lead image: Codex Forster II , Leonardo da Vinci, late 15th – early 16th century, Italy. Museum no. Forster MS.141. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Via: The Royal Collection

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.