The Windmill Theatre, April 1958.

It was reported last year in London’s Evening Standard that the Windmill Theatre, once celebrated for never closing and still remembered as a major symbol for London’s Blitz spirit, was to be ‘reborn’ as a ‘celebrity cocktail bar’. The building, a stone’s throw from Piccadilly Circus and Shaftesbury Avenue, had actually been empty for a year. The Windmill International Lap Dancing club that advertised itself, improbably, as ‘probably the most exciting men’s club in the world’ had lost its adult entertainment licence when its dancers were found to be flouting the “no touching” rules.

The Windmill Theatre started life in 1931 after the Palais-de-Luxe, a former cinema on the corner of Archer Street and Great Windmill Street, was bought the year before and turned into a small theatre by Mrs Laura Henderson. The street, and thus the theatre, had taken its name from a windmill on the site first recorded in 1585 and demolished about 100 years later. Mrs Henderson’s husband, a Bengal Jute merchant, had died in 1919 and left her everything in his will. It was not an insubstantial sum not least because it was estimated that 1.3 billion jute sandbags had been needed during World War One.

The Palais-de-Luxe, one of London’s first purpose-built cinemas, had been constructed in 1909 opposite the Red Lion public house where in November 1847 the Communist League had held its second congress in a room above the bar. It was here that Karl Marx and Frederick Engels submitted their initial draft of the Communist Manifesto which was published just a few months later.

Albeit not purpose-built, Soho’s first cinema had opened in 1908 about 100m away on Ingestre Place. Called the Electric Cinema Theatre it was actually just a crude conversion of a stable yard with planks of wood for a roof, a screen erected over the manger and the horse stalls still in place. For one penny (cheap even for the time) 120 people sat on boxes and wooden benches to watch an hour long show accompanied by an early electric piano.

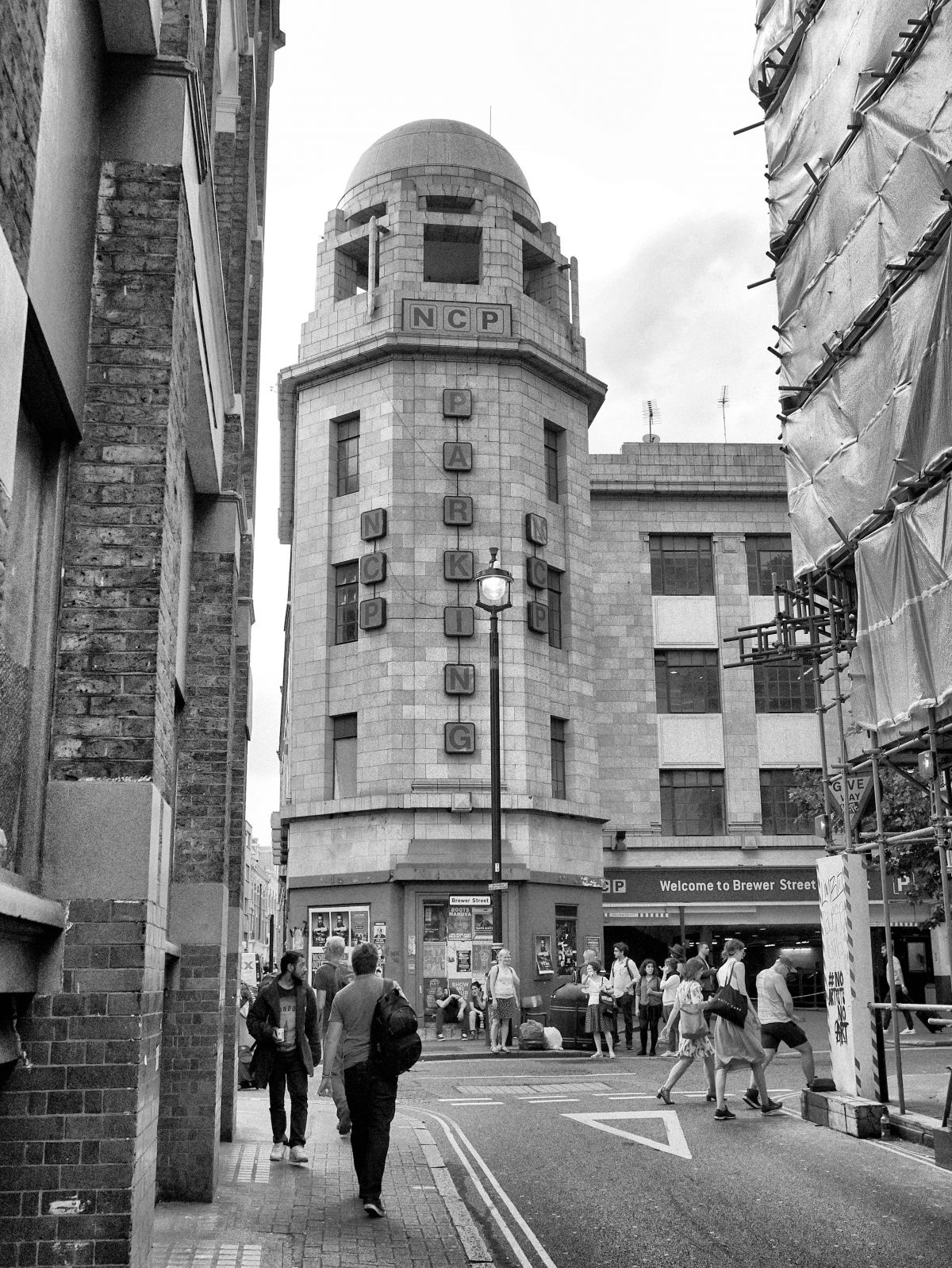

By the end of the 1920s neither picture-house was able to compete with the new super-cinemas opening around London. The Electric Theatre went when much of the area to the north of Great Windmill Street and Brewer Street was demolished to be replaced by the Lex Garage – maybe the only multi-story car-park in the world that has ever been described as glamorous. Erected in 1929 it was described as ‘probably the largest and best-equipped building for the service of the motor-car that has yet appeared in this congested city’. It was intended to serve the West End, especially ‘Theatreland’, for which increasing numbers were coming in by car. Inside the terracotta-tiled art-deco building there were vehicle-turntables on each floor, a chauffeurs’ canteen, a restaurant, and theatrical and travel agencies. On the ground floor there was a shop and petrol pumps in the forecourt. At night it was floodlit, with searchlights shining into the dark sky. The building still stands and is now the Brewer Street NCP [https://www.ncp.co.uk/find-a-car-park/car-parks/london-brewer-street/] car park. It costs £17 an hour to leave your car there and it is now a grade II listed building.

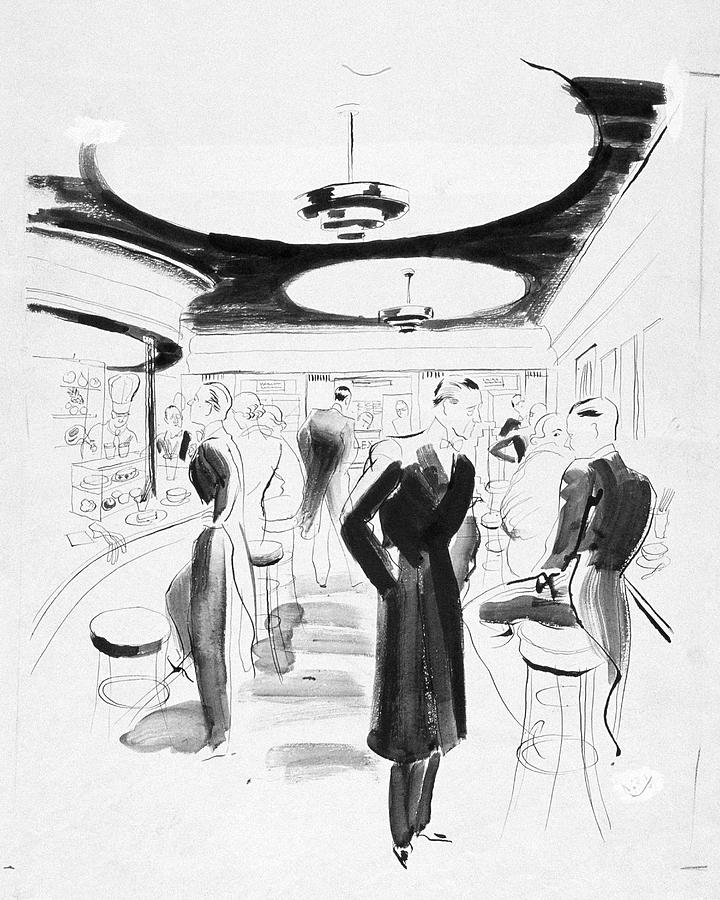

The snack bar in the Lex Garage on Brewer Street by Renbout Willaumez in 1931

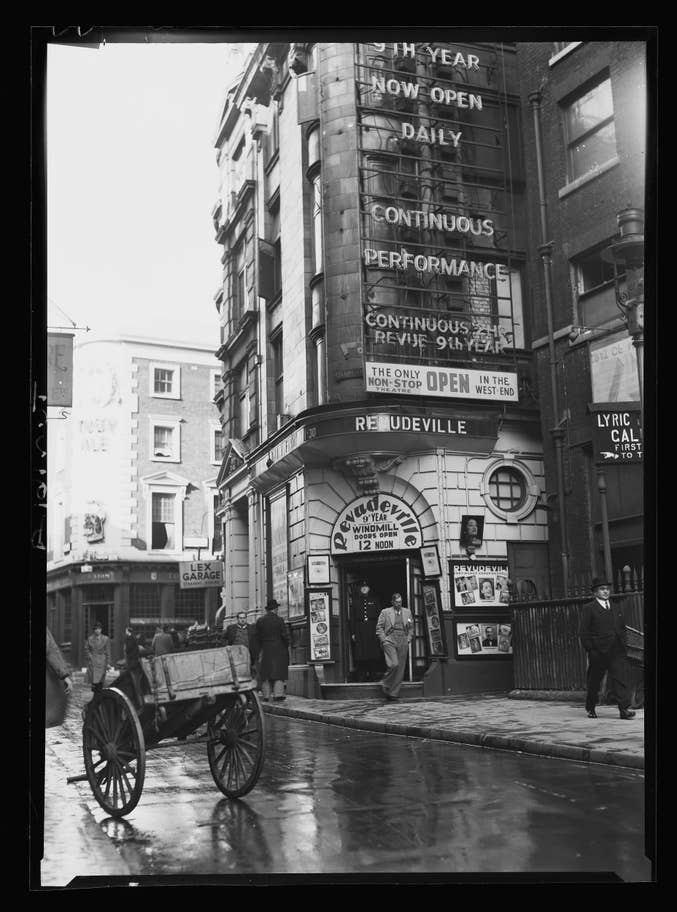

Pedestrians crossing Great Windmill Street, Soho, London in 1930

A year after the Lex Garage was open for business Mrs Henderson had her former cinema extensively rebuilt, and just like the Lex, it was faced with glazed terracotta. Renamed the Windmill Theatre it’s first play ‘Inquest’ was a failure and she briefly turned the theatre into a cinema to show the relatively new ‘Talkies’.

It was when she employed Vivian Van Damme that everything changed. The jewish son of an East-End solicitor Van Damme slowly changed the theatre’s fortune. His idea was to present a non-stop revue that had a dancing troupe, a singer or two and some brand-new comedians but, most importantly, it soon included, as he once put it, “perfectly proportioned young women presented in artistic poses’. Half-naked women standing like statues was seen by many as innovation that somehow got past the strict theatre censors but Tableaux Vivants or Living Pictures had actually been seen in London’s theatres from the mid-19th century. If looking at stationary naked women was your thing, it had long been a loophole in the law. The Lord Chamberlain, the Government’s official theatre censor, Rowland Baring the 2nd Earl of Cromer summed up it up at the time “It’s all right to be nude, but if it moves, it’s rude.” Baring saw the theatre as a sort of “national safety valve” although performers had to have a ‘normal figure’ and women with big breasts would not be allowed. In fact the Windmill almost had more problems during the 1930s with the comedians’ political material than any nakedness. The Lord Chamberlain was worried that the character of ‘Signor Whale-Blubber’, a clear reference to Mussolini, might offend ‘sensitive foreigners’ and even as late as 1939, the theatre censors, extraordinary, were putting red lines through negative impressions of Hitler and Mussolini and even censoring such words as ‘Nordic’ and ‘Concentration Camp’.

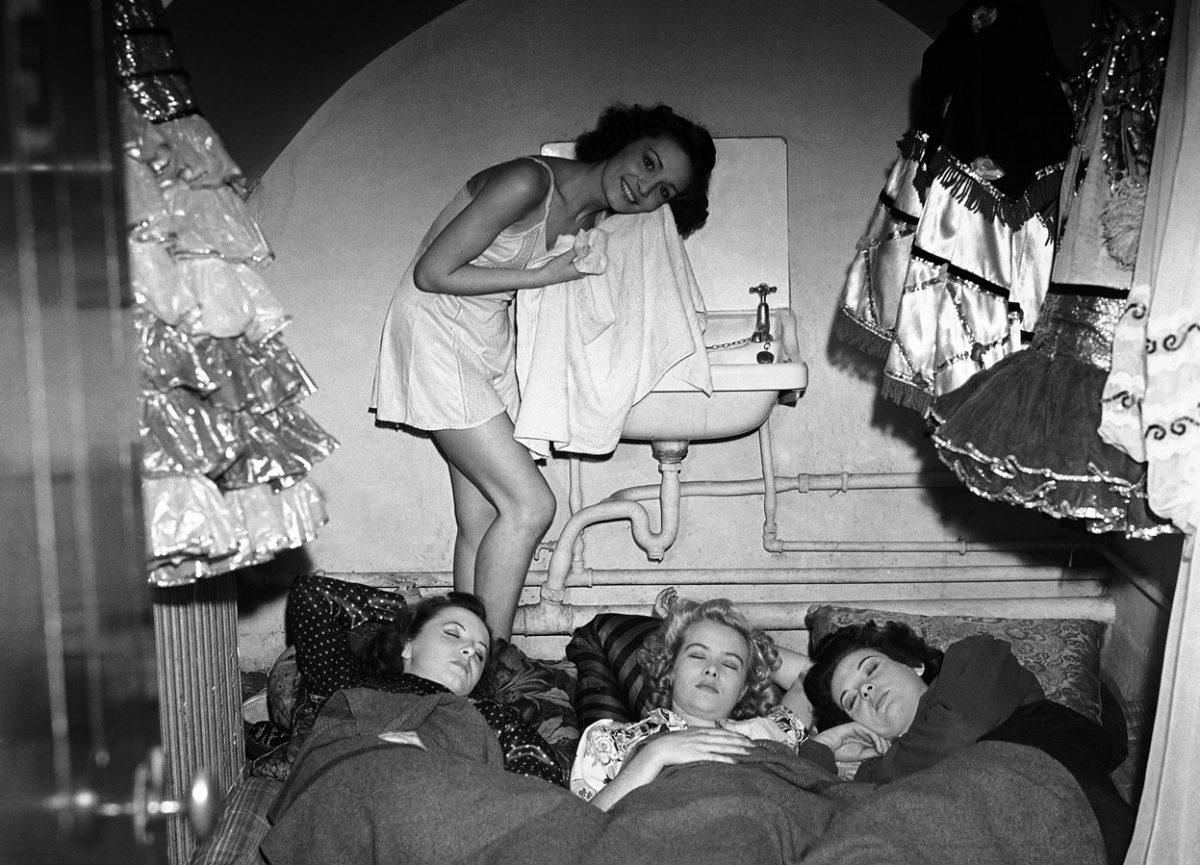

At the beginning of WW2 the government ordered compulsory closure of all the theatres in the West End – a stricture that, due to much protest, ended less than two weeks later. The Windmill re-opened immediately and stayed open throughout the rest of the war with five or six performances a day. Around 1943 the theatre created its famous motto – ‘We never closed’. It was during the war that the Windmill Theatre became a national institution and throughout the world as an embodiment of London’s ‘Blitz Spirit’. This was often illustrated by similar stories of a naked young woman breaking the no-moving rule by either giving a V-sign or thumbing her nose at a nearby exploding bomb. One elaborate version had the woman shrieking and running off stage after a nearby explosion caused a dead rat to fall from the rafters. Apocryphal or not performing on stage during the worst of the Blitz must have often been terrifying. It was often too dangerous to expect people to get home safely and the stagehands and performers would sleep in the lower two floors underground. The nearby Lex Garage had a shelter in the basement that had space for 1000 people.

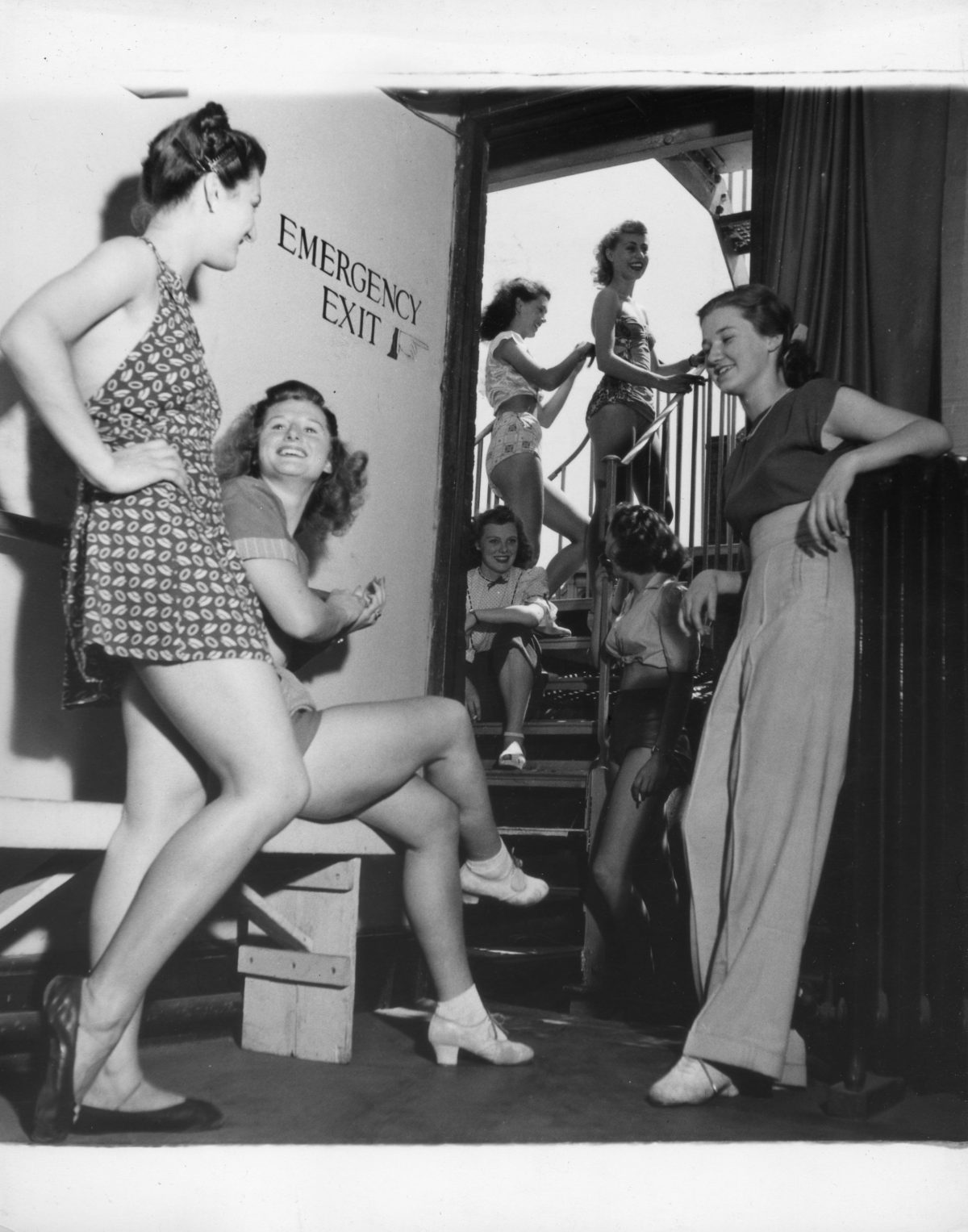

Windmill Girls during the war

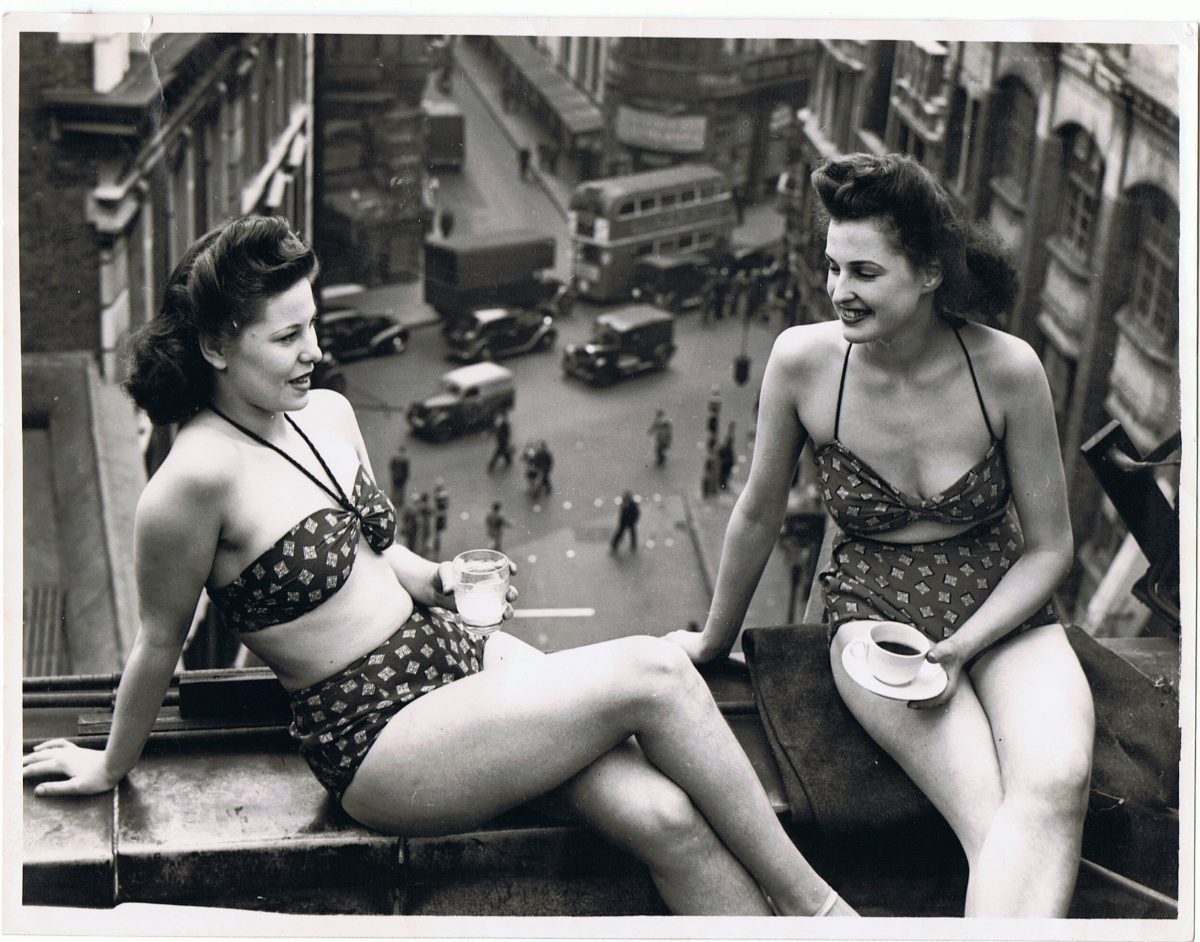

The Windmill girls dash across London’s Soho to a party in 1953

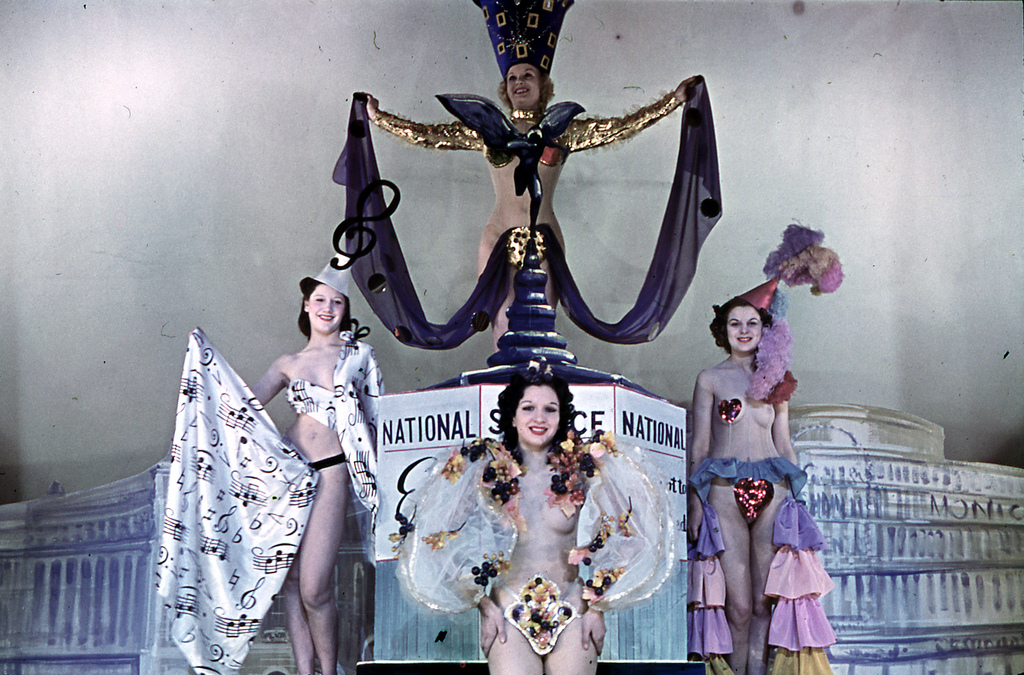

A member of the Windmill Girls dance troupe performing in the show ‘Paris by Night.. Before 1940’, on stage at the Windmill Theatre

The Windmill Theatre, London, which prided itself on staying open throughout the War – circa 1940

In November 1944 Mrs Henderson at the age of 80 died not from a bomb but old age and the woman that he called “a little bundle of dynamite” left everything to him. As was her wish Revudeville carried on as before. What Van Damm managed to do at the Windmill was to sell sex combined with a sort of tasteful ‘girl-next-door’ version of English femininity. One critic during WW2 managed to imagine that he was at the Folies Bergère but only for a few fleeting moments as the theatre “seemed to be tinged with an air of Tooting respectability”. The Los Angeles Times, writing of the theatre in 1952 wrote “by the time a Shropshire lass goes on stage dressed in nothing but cosmetics and the Lord Chamberlain’s blessing, she’s concealing very little. And her staid audience if not yelling or whistling, is at least murmuring gently in appreciation.”

Graham Greene, in a wartime Spectator article, had noticed this odd lack of bawdiness when he noticed the difference between the Windmill and an old-fashioned, boisterous music-hall: “there is almost a religious air’ he wrote, ‘of muffled footsteps and private prayers: people don’t often laugh at the jokes any more than they do at jokes from the pulpit.” To be fair most of audience weren’t there for laughs and it was a tough crowd for any comedian. Tony Hancock once remembered that men would stop him outside the Windmill and say: “My dear chap, I did enjoy your act… could you possibly arrange an introduction to the third girl from the left?” But the list of comics and entertainers who began their career performing at the Windmill is extraordinary and included Jimmy Edwards, Tony Hancock, Arthur English, Harry Secombe, Peter Sellers (not his first appearance at the Windmill. As a child he had performed in a show with his mother Peg, who was a burlesque dancer at the theatre not long after it opened) Michael Bentine, Bruce Forsyth, Dave Allen, Alfred Marks, Max Bygraves, Tommy Cooper and Barry Cryer. There was a comedy revolution after war and performers who, in a sense, had wasted years of their young adulthood, were desperate to make up for lost time. They had seen the best of humanity but, of course, the worst and had a connection with each other like no generation since.

Doreen Lord and Beryl Catlin up on the roof of the Windmill c.1950

Windmill Theatre up to the roof Mellonie Whymark, Anita D’Ray and Annette Gibson c.1950 – courtesy of Jill Shapiro

In the end it wasn’t censorship that caused the Windmill’s famous Revudeville to close but actually the lack of it. Initially after the war the authorities tried to temper down the anything-goes wartime spirit but despite the Lord Chamberlain’s office sending their splendidly named official George Titman to inspect the shows – Revudeville carried on without many changes. A frail Vivian Van Damm died in December 1960 but by then his daughter Sheila was in charge. Later writing, “I spoilt my nudes outrageously. I admit it. But beautiful girls who can sing and dance, and agree to take off their clothes in public are rare indeed. They are pearls belong price to be cosseted, pampered and humoured.” In 1964, however, she announced to the press: “Because of the times, the strip clubs and the sexy films, we have become too respectable for frustrated old men,” she explained. “We are a frustrated nation,” “Our audience has been a lot of frustrated gentlemen. I prefer to call them that rather than dirty old men, which is what they were really.” The Windmill didn’t really stand a chance. Soho had become the centre of striptease in London and it was said that every night over a thousand girls were ‘peeling off’ in front of thousands of voyeurs. In her memoir ‘We Never Closed’ she writes that the Windmill was not the den if iniquity outsiders imagined it to be: ‘Our fan dance was usually such a masterpiece of timing it could have been performed at a vicarage fête with scarcely a tut-tut of embarrassment.’

Jill Millard Shapiro outside the Windmill

Sheila Van Damm, courtesy of Jill Millard Shapiro

Sheila Van Damme

At the time Sheila Van Damm was known more to the public as a very successful woman rally driver. During the war she had enrolled in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force and was taught to drive very fast as a military courier. In 1950, Mr Van Damm entered his daughter in the Daily Express rally (the first since the war) which involved driving a thousand miles in 48 hours. Incredibly Sheila and her team came third, albeit with the help of what Ms Van Damme called ‘wakey-wakey’ pills. Impressed the Rootes factory invited the team to the 1951 Monte Carlo in a works Hillman Minx – where she won the Coupe des Dames. In the 1953 Alpine Rally she won he Women’s European Touring Championship and in 1955 the Coupe des Dames at the Monte Carlo Rally – after which she retired.

What the country didn’t know was that Sheila Van Damm led a most unconventional life. From around 1958 Sheila lived in a ménage à trois first at Clareville Grove in South Kensington and later in Clapham with the very famous broadcaster and journalist Nancy Spain and her partner Joan Werner Laurie – the editor of She magazine. The three were very close indeed. “We all knew she was a lesbian”, former Windmill Girl Jill Millard Shapiro told me, “but that didn’t bother anybody. Don’t forget a lot of the boy performers were gay. We were used to it. She looked big and butch but you could always win her round.”

Plane crash near Aintree

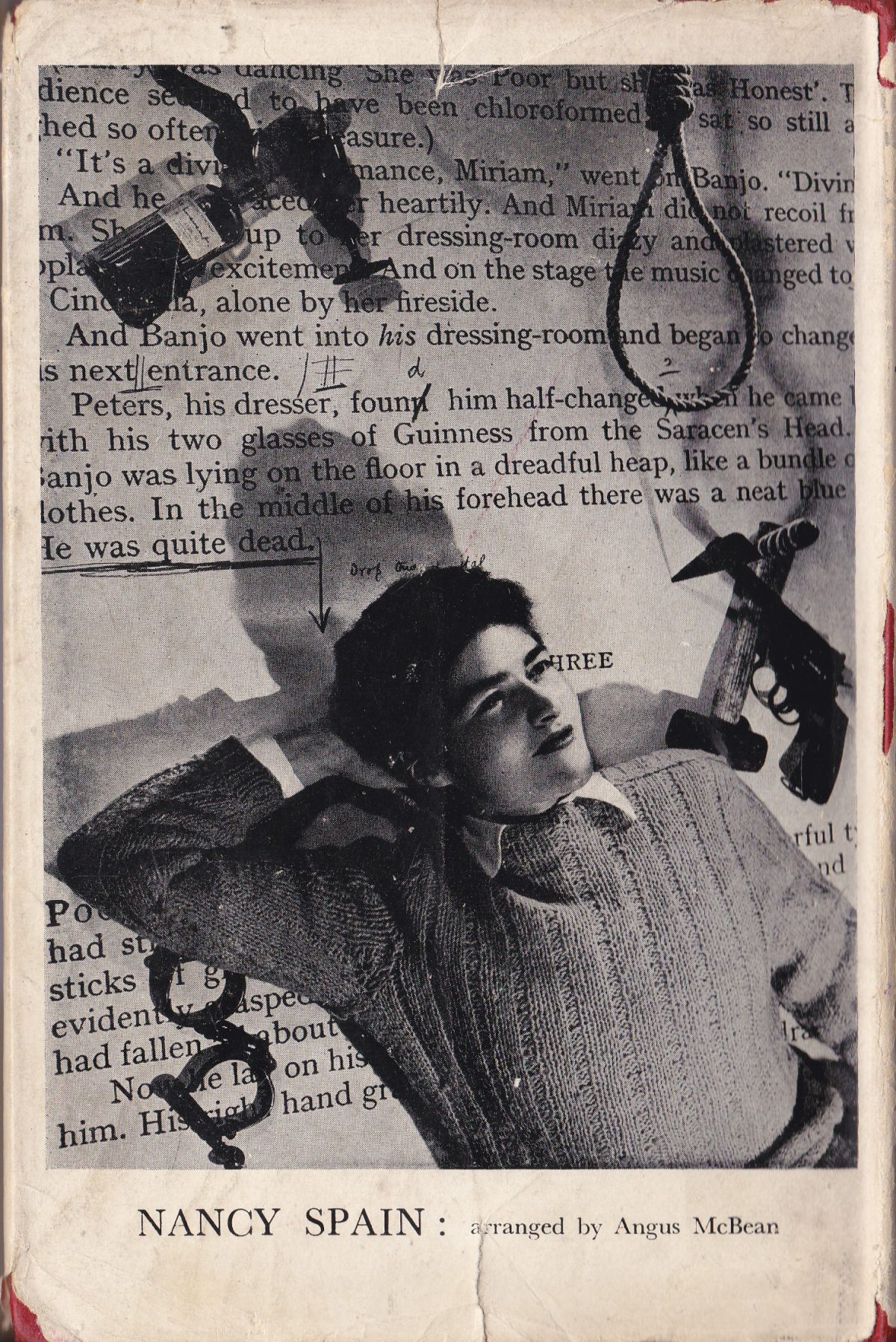

Nancy Spain by Angus McBean

By the end of 1964 Revudeville had run longer than any show on earth, at some sixty thousand performances although the theatre had only 320 seats, more than ten million people had seen it. But it had been a very tough year for Sheila. Earlier that year, on 21 March 1964 her two close friends Nancy and Joan, along with three others, died when their Piper Apache aircraft crashed in a field of cabbages near Aintree racecourse on the way to watch the Grand National. Sheila was already there waiting for them.

Seven months later the Windmill officially closed. Within two days the new owners turned it back into a cinema and opened with the film Nude Las Vegas. Ten years later Paul Raymond announced that he would open the Windmill as a theatre again although it was going to be different than Revudeville:

The whole idea of the Windmill was girls, girls, girls, with a guy telling a few gags in between. We won’t be doing this for one thing the Japanese and German visitors wouldn’t understand them. We’ll keep the sport of “we never closed,” but as as for the rest, forget it.

Raymond who left school at fifteen bought a secret code mind readers used to use in their acts for 25 quid from a couple who operated on the Clacton Pier.” He wasn’t very good and his act ultimately failed but he noticed that “when the birds left, so did the audience. It made me realise where the future lay, and that it was not in mind-reading.”

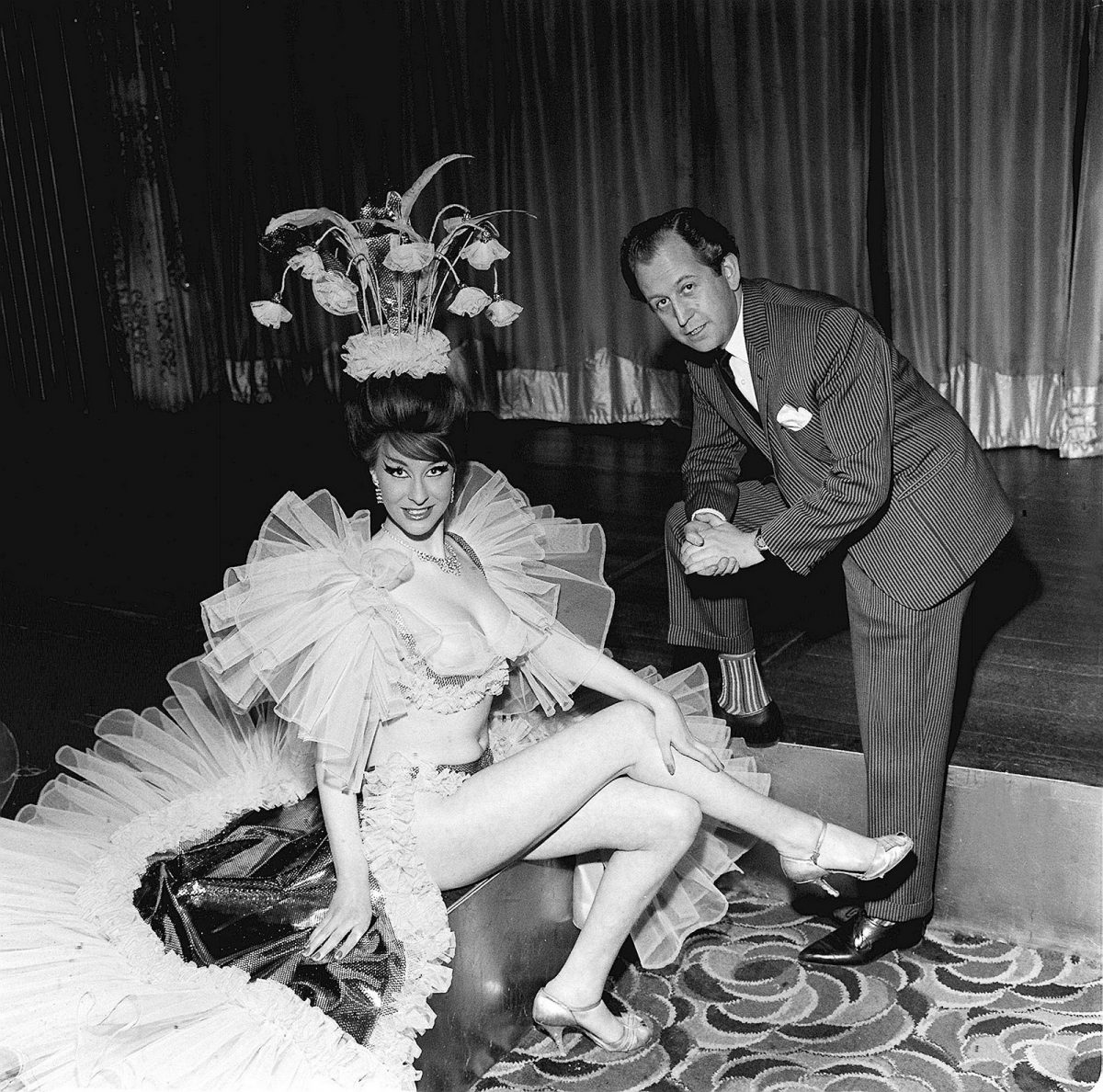

Paul Raymond – founder of Raymond’s Revue Bar in Soho, London May 1962

Windmill Theatre, Great Windmill Street, 1972 – courtesy of the Glen Fairweather Archive

Not even close… from 2015

Lex Garage in 2018, photo by Rob Baker

Windmill Theatre in 2012, photo by Rob Baker

The venue became Paramount City in May 1986, a cabaret club managed for a short duration by Debbie Raymond, Paul Raymond’s daughter and then for a short period it became a small television studio. The show Paramount City came from there and although not a storming success some of the comedians who appeared there Steve Coogan, Jack Dee, Frank Skinner, Caroline Aherne, Jo Brand and Jeremy Hardy ended up with careers as big as the first generation of Windmill comedians.

A few years before Simon Cowell, along with his former boss at EMI Ellis Rich, set up a business called E&S Music in the disused toilets of the old Lex Garage. Simon’s father, Eric Cowell, was friends with Donald Gosling who owned NCP and recommended the place. The glamorous days of Lex Garage had long gone. Rich once said ‘So we went along and it was horrible, it smelt, it still had the bottoms of the soil pipes where the toilets used to be, so we balanced the secretary’s desk over that – but the location was fantastic!’

The location is still fantastic, around the corner from Piccadilly Circus on the edge of a not-so-edgy Soho. But there’s no need to cater for the ‘frustrated gentlemen’ and they probably stay indoors these days and the Red Lion is now the Be At One cocktail bar [https://www.beatone.co.uk/cocktail-bar/piccadilly-circus] .It ’s soon to be joined by the Windmill Cocktail Bar. Any socialists presenting political manifestos these days would only be of the champagne variety.

With many thanks to the wonderful Jill Millard Shapiro for our conversations and help with pictures.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.