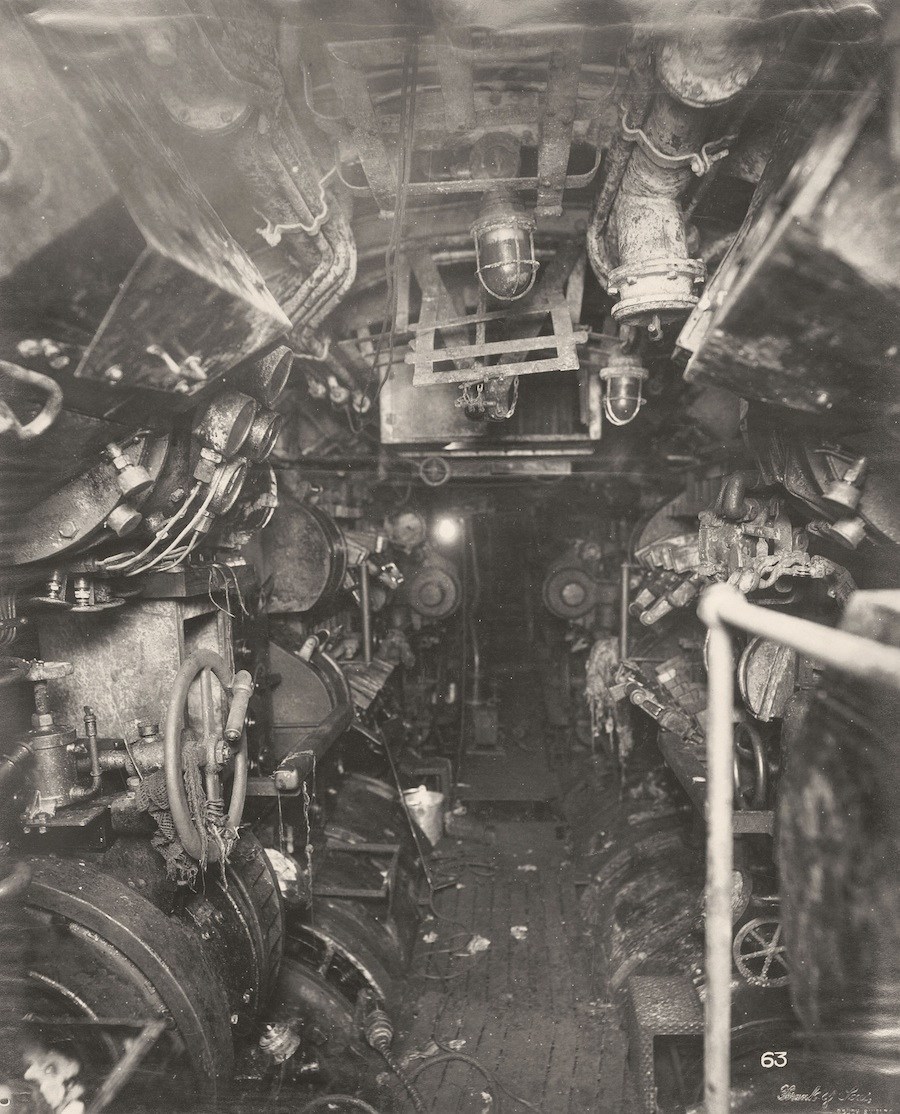

Like the innards of some hellish behemoth gutted on the banks of the Tyne, these photographs show the cramped, claustrophobic interior of U-boat 110.

On 19th July 1918, U-boat 110 was making an approach on a convoy of Allied merchant ships off the Hartlepool coast when her periscope was spotted by H. M. Motor-Launch No. 236. Several ships within the convoy dropped depth charges. The U-boat was hit. Its forward rudders jammed in the up position. Her motor short circuited and the fuel tank was badly damaged.

As the submarine surfaced she was rammed twice by torpedo boat destroyer H.M.S. Garry. The submarine rolled over and sank. Thirteen crew died–as many as fifteen survived.

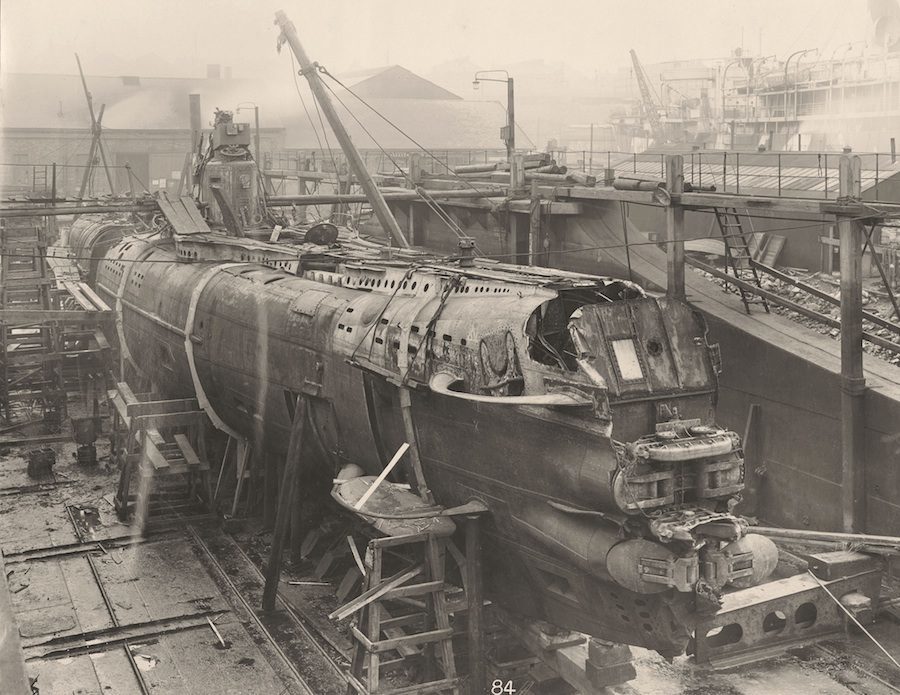

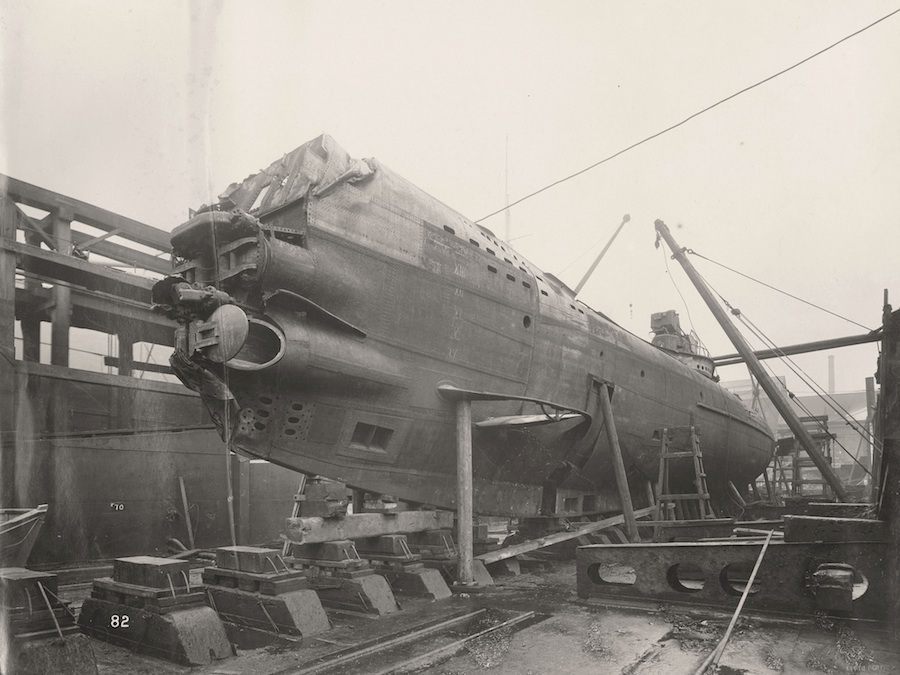

In September, the U-boat was salvaged and then berthed at Swan Hunter’s dry docks. The shipyard had orders to restore the submarine as a fighting unit.

When the Armistice was declared on 11th November 1918, work on the U-boat was halted.

On 19th December, the submarine was towed from Wallsend to the Northumberland Dock at Howdon. Here U-boat 110 was sold for scrap.

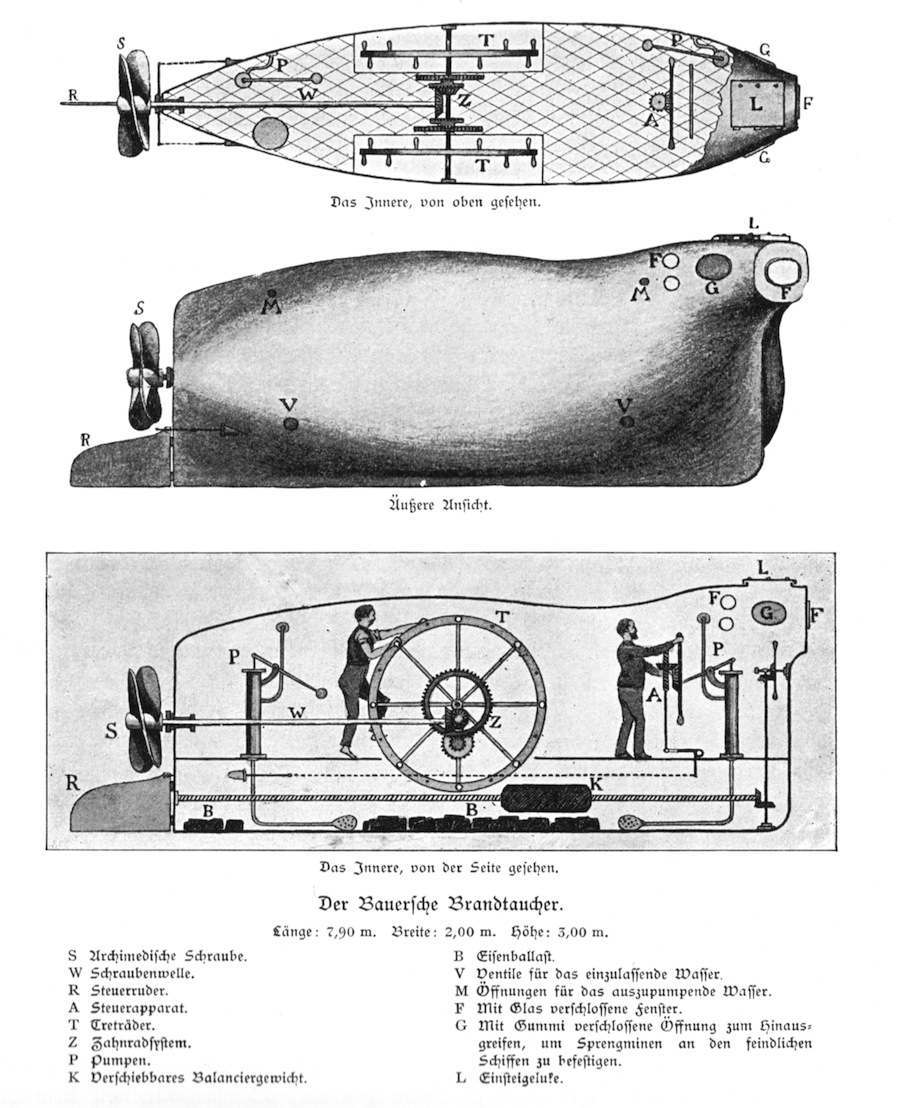

The history of the first U-boat, or the first submarine, is a long and complex tale–suffice to say one of the earliest prototypes for submarine–or Unterseeboot or U-boat–was devised by Bavarian inventor and engineer Wilhelm Bauer in the late 1840s.

Bauer wanted to find something more efficient than incendiary ships as a way to break a naval blockade–these were ships loaded with explosives allowed to sail into the midst of an enemy’s fleet before being detonated. He decided on using an underwater boat as a more efficient way to carry explosives (mines) into the midst of an enemy’s fleet to cause devastation.

When he made a workable model of this underwater boat, Bauer was given money to build full-scale Brandtaucher Submarine.

Bauer’s plans for an underwater boat.

The vessel was 28 feet long and weighed around 70,000 pounds. This submarine carried a three-man crew–two operators, one captain. Once the Brandtaucher had positioned itself beneath an enemy ship, the captain would open a small hatch and attach a mine to the hull of his target. This would be detonated once the submarine was successfully clear of the area.

However, things did not go according to plan. Due to a design fault the Brandtaucher quickly filled-up with water and sank during its first presentation show in 1851. The vessel settled into the mud and its crew escaped.

Having lost the support of the Schleswig-Holstein government, Bauer continued with his designs and was eventually commissioned by the Russians to build a Seeteufel (“Sea Devil”) submarine. Bauer made several improvements to this vessel–including an airlock that allowed access to and from the submarine while underwater. It had 133 successful submersions, but was caught on a sand bed on its 134 mission.

Though Bauer failed to see his Seeteufel adopted by either Germany or Russia, his experimentation was an influence and inspiration to many of the submarine engineers who followed him.

The Swedish inventor Thorsten Nordenfelt and English clergyman George Garrett were also pioneers of submarine design.

Garrett built a 14-foot long hand-cranked submarine called the Resurgam in 1878, which weighed around four-and-a-half tons.

Nordenfelt built the Nordenfelt I–a 64-foot, 56 ton vessel that was also armed with a single torpedo and machine-gun. He built for the Ottoman Empire, the Nordenfelt II (Ottoman submarine Abdül Hamid) and Nordenfelt III. In 1886, the Abdül Hamid became the first submarine to fire a torpedo underwater.

In 1910, Germany built the first of its many U-boats, SM U-21. The SM U-21 was the first U-boat to sink a British vessel H.M.S. Pathfinder on 5th September 1914.

Of the 375 U-Boats that set sail from Germany during the First World War, 202 were lost in action–either destroyed by Allied ships or sunk by mechanical failure or accidents.

U-boats presented a new form of warfare–sinking around 2,600 ships during the conflict. Of the 17,000 Germans who served on U-Boats, 5,100 lost their lives.

In 1914, First Watch Officer Johannes Speiss of the U-boat U9 wrote a short article documenting his experience life on board the kerosene-powered vessel. Unlike later diesel- powered U-boats, this kerosene powered submarine required a funnel to disperse the smoke and fumes.

“Living aboard U9 in 1914“

“Far forward in the pressure hull, which was cylindrical, was the forward torpedo room containing two torpedo tubes and two reserve torpedoes. Further astern was the Warrant Officers’ compartment, which contained only small bunks for the Warrant Officers (Quartermaster and Machinist) and was particularly wet and cold.

“Then came the Commanding Officer’s cabin, fitted with only a small bunk and clothes closet, no desk being furnished. Whenever a torpedo had to be loaded forward or the tube prepared for a shot, both the Warrant Officers’ and Commanding Officers’ cabins had to be completely cleared out. Bunks and clothes cabinets then had to be moved into the adjacent officers’ compartment, which was no light task owing to the lack of space in the latter compartment.

“In order to live at all in the officers’ compartments a certain degree of finesse was required. The Watch Officer’s bunk was too small to permit him to lie on his back. He was forced to lie on one side and then, being wedged between the bulkhead to the right and the clothes-press on the left, to hold fast against the movements of the boat in a seaway. The occupant of the berth could not sleep with his feet aft as there was an electric fuse-box in the way. At times the cover of this box sprang open and it was all too easy to cause a short circuit by touching this with the feet. Under the sleeping compartments, as well as through the entire forward part of the vessel, were the electric accumulators which served to supply current to the electric motors for submerged cruising.

“On the port side of the officer’s compartment was the berth of the Chief Engineer, while the centre of the compartment served as a passageway through the boat. On each side was a small upholstered transom between which a folding table could be inserted. Two folding camp-chairs completed the furniture.

“While the Commanding Officer, Watch Officer and Chief Engineer took their meals, men had to pass back and forth through the boat, and each time anyone passed the table had to be folded.

“Further aft, the crew space was separated from the officers’ compartment by a watertight bulkhead with a round watertight door for passage. On one side of the crews space a small electric range was supposed to serve for cooking – but the electric heating coil and the bake-oven short-circuited every time an attempt was made to use them. Meals were always prepared on deck! For this purpose we had a small paraffin stove such as was in common use on Norwegian fishing vessels. This had the particular advantage of being serviceable even in a high wind.

“The crew space had bunks for only a few of the crew – the rest slept in hammocks, when not on watch or on board the submarine mother-ship while in port.

“The living spaces were not cased with wood. Since the temperature inside the boat was considerably greater than the sea outside, moisture in the air condensed on the steel hull-plates; the condensation had a very disconcerting way of dropping on a sleeping face, with every movement of the vessel. Efforts were made to prevent this by covering the face with rain clothes or rubber sheets. It was in reality like a damp cellar.

“The storage battery cells, which were located under the living spaces and filled with acid and distilled water, generated gas [hydrogen gas] on charge and discharge: this was drawn off through the ventilation system. Ventilation failure risked explosion, a catastrophe which occurred in several German boats. If sea water got into the battery cells, poisonous chlorine gas was generated.

“From a hygienic standpoint the sleeping arrangements left much to be desired; one ‘ awoke in the morning with considerable mucus in the nostrils and a so-called ‘oil-head’.

“The central station was abaft the crew space, dosed off by a bulkhead both forward and aft. Here was the gyro compass and also the depth rudder hand-operating gear with which the boat was kept at the required level similar to a Zeppelin. The bilge pumps, the blowers for clearing and filling the diving tanks – both electrically driven – as well as the air compressors were also here. In one small corner of this space stood a toilet screened by a curtain and, after seeing this arrangement, I understood why the officer I had relieved recommended the use of opium before all cruises which were to last over twelve hours.

“In the engine room were the four Korting paraffin [kerosine] engines which could be coupled in tandem, two on each propeller shaft. The air required by these engines was drawn in through the conning-tower hatch, while the exhaust was led overboard through a long demountable funnel. Astern of the gas engines were the two electric motors for submerged cruising.

“In the stem of the boat, right aft, was the after torpedo room with two stem torpedo tubes but without reserve torpedoes.

“The conning tower is yet to be described. This was the battle station of the Commanding Officer and the Watch Officer. Here were located the two periscopes, a platform for the Helmsman and the ‘diving piano’ which consisted of twenty-four levers on each side controlling the valves for releasing air from the tanks. Near these were the indicator glasses and test cocks.

“Finally there was electrical controlling gear for depth steering, a depth indicator; voice pipes; and the electrical firing device for the torpedo tubes.

“Above the conning tower was a small bridge which was protected when cruising under conditions which did not require the boat to be in constant readiness for diving: a rubber strip was stretched along a series of stanchions screwed into the deck, reaching about as high as the chest. When in readiness for diving this was demounted, and there was a considerable danger of being washed overboard.

“The Officer on Watch sat on the hatch coaming, the Petty Officer of the Watch near him, with his feet hanging through the hatch through which the air for the gas engines was being drawn. I still wonder why I was not afflicted with rheumatism in spite of leather trousers. The third man on watch, a seaman, stood on a small three-cornered platform above the conning tower; he was lashed to his station in heavy seas.

“This was the general arrangement for all seagoing boats at that time of the Types U-5 to U-18 with few exceptions.”

U-boat 110 was built by Blohm & Voss Shipyards in Hamburg. It was launched on 1st September 1917 and commissioned on 23rd March 1918.

The U-boat was captained by Kapitänleutnant Werner Fürbringer. U-boat 110 had two patrols–sinking one ship and badly damaging another. During his career Fürbringer (1888-1982) was responsible for sinking a total of 101 ships and damaging five. He survived the sinking of U-boat 110, serving the remainder of the conflict as a P.O.W. He returned to Germany in 1920, when he retired from naval service.

U-Boat 110: A German Submarine that was sunk and salvaged in 1918.

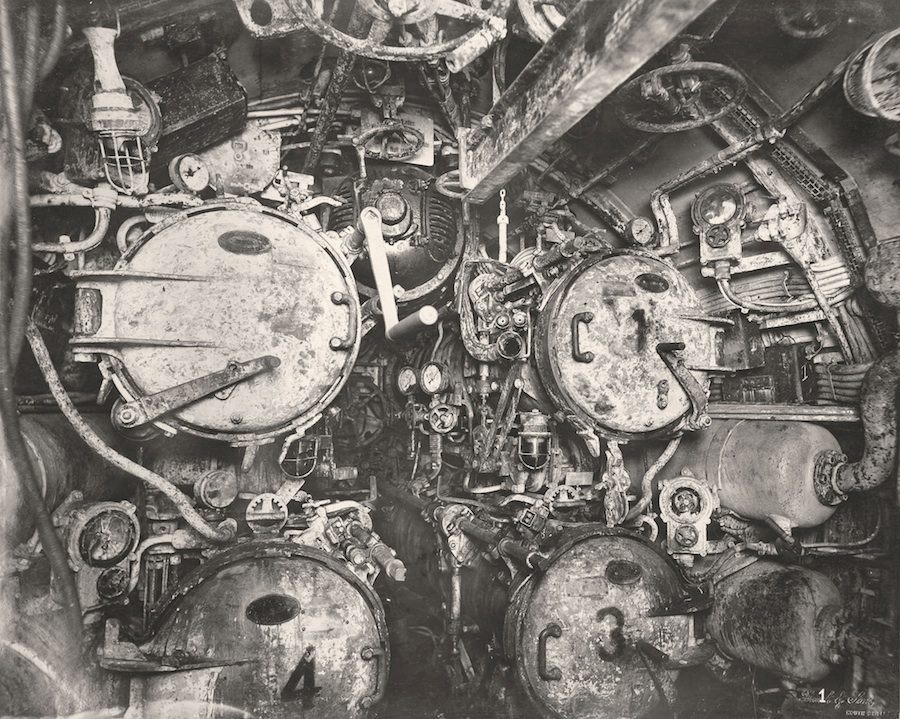

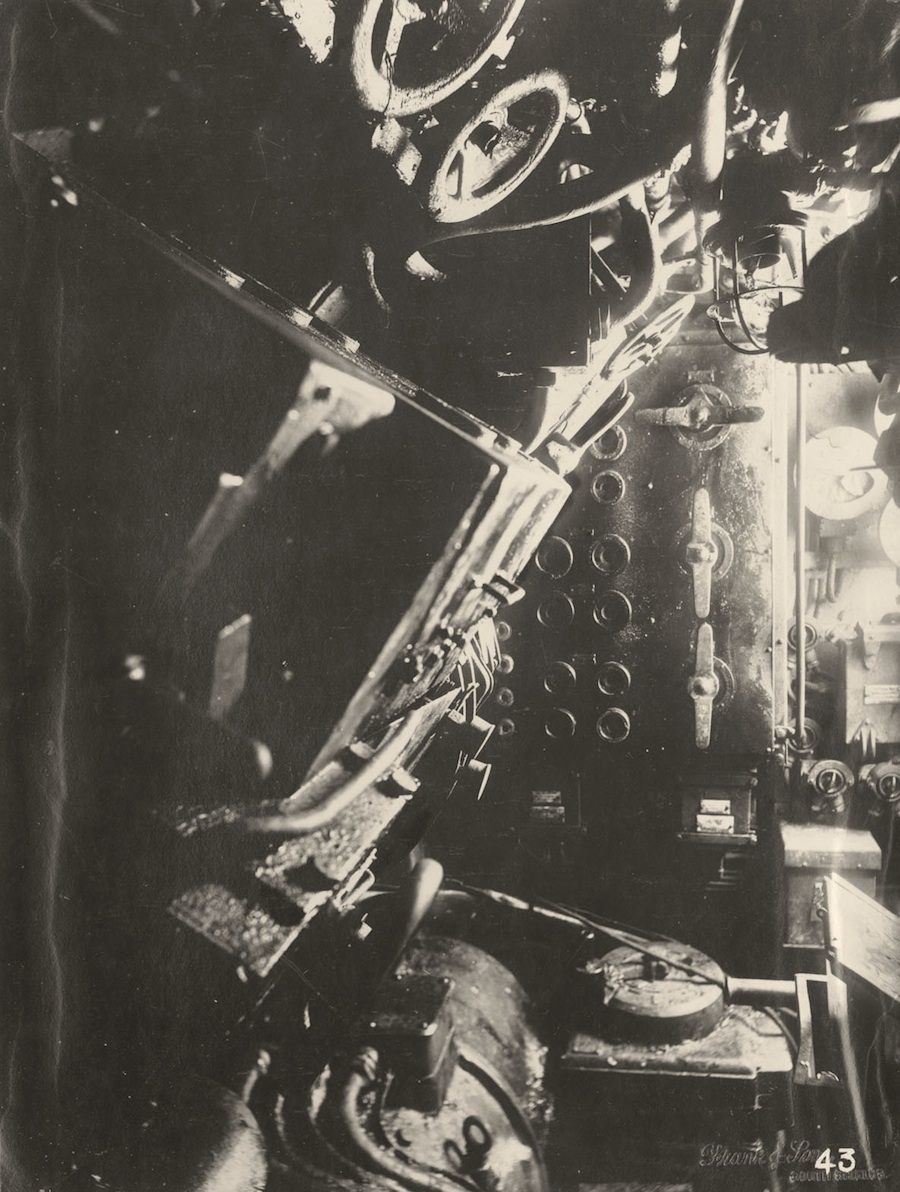

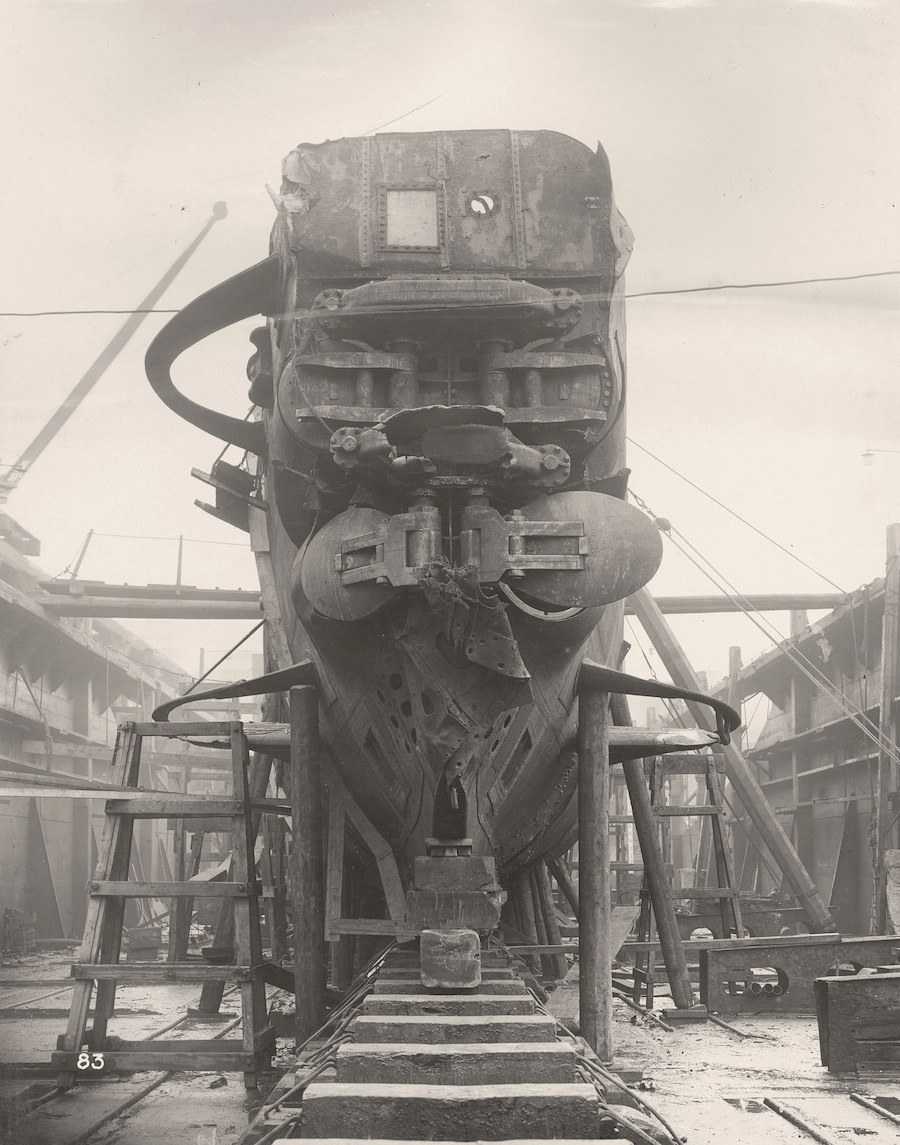

A side view of the U-Boat’s four bow Torpedo Tubes and the hydroplane on its port side.

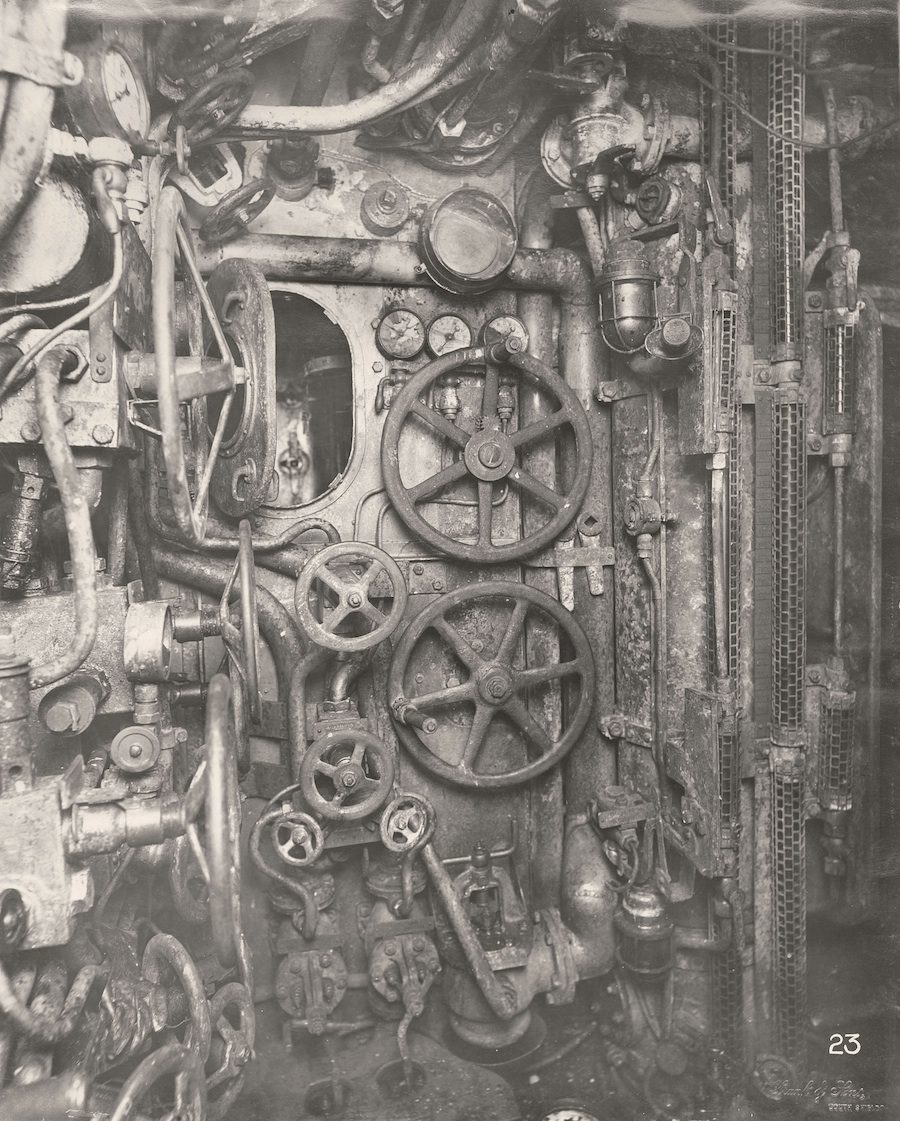

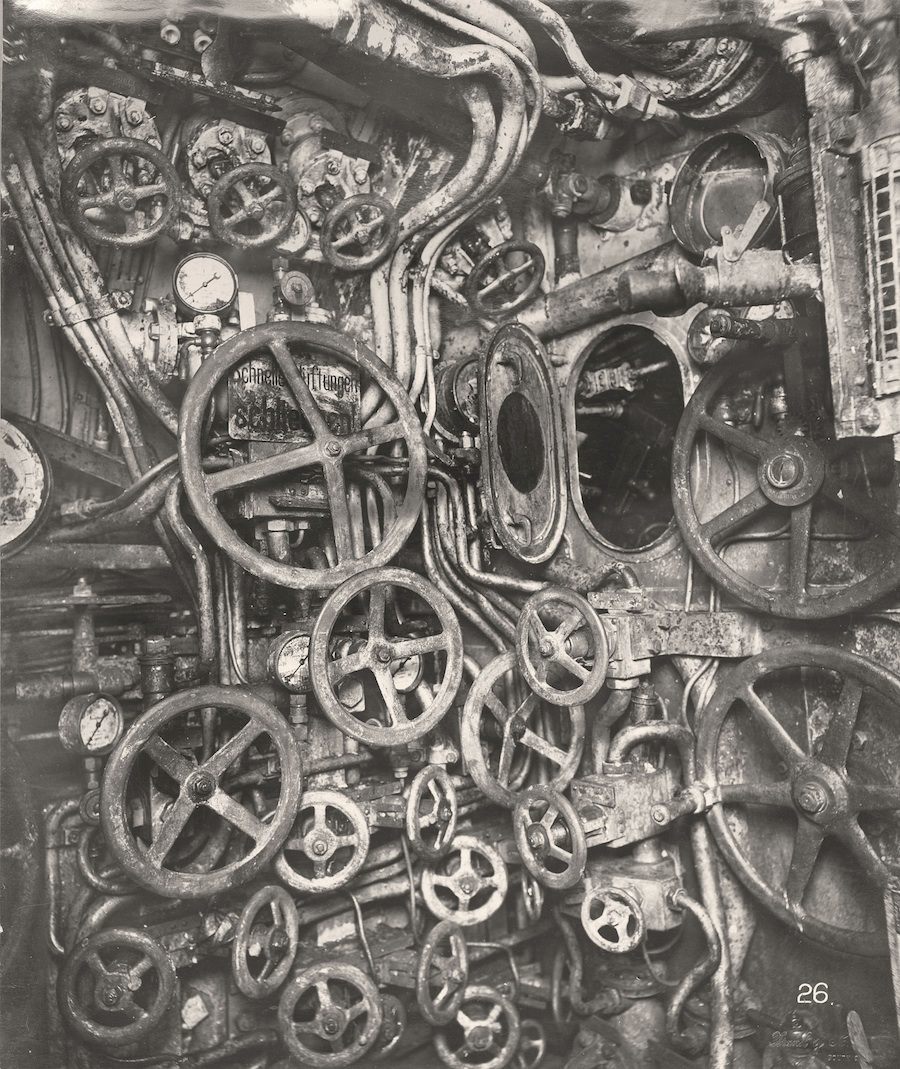

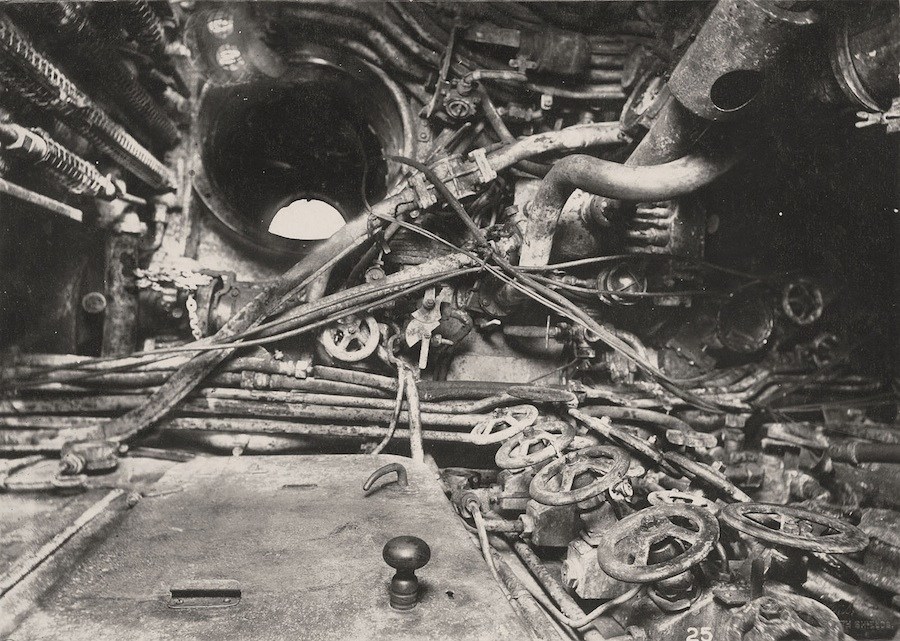

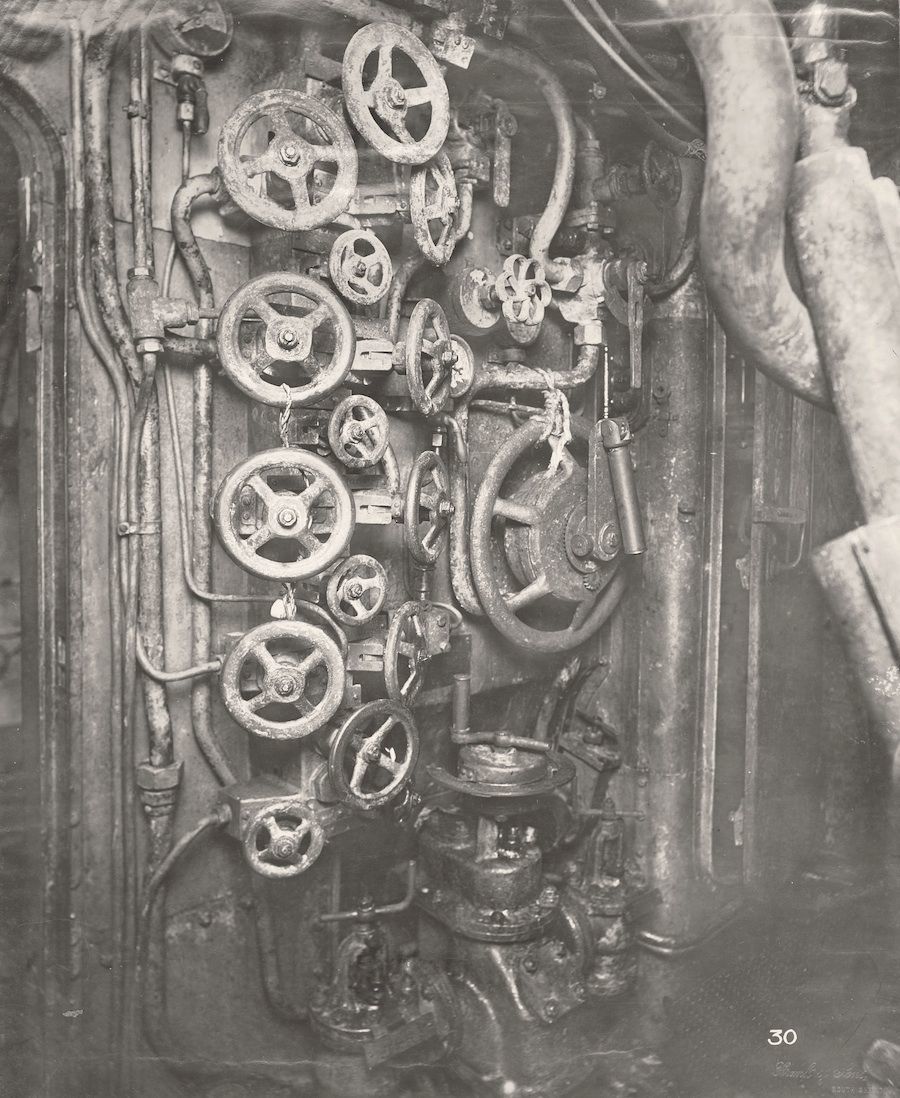

This is a view of the Control Room showing the “manhole to the periscope well, hand wheels for pressure gear, valve wheels for flooding and blowing and the air pressure gauges.”

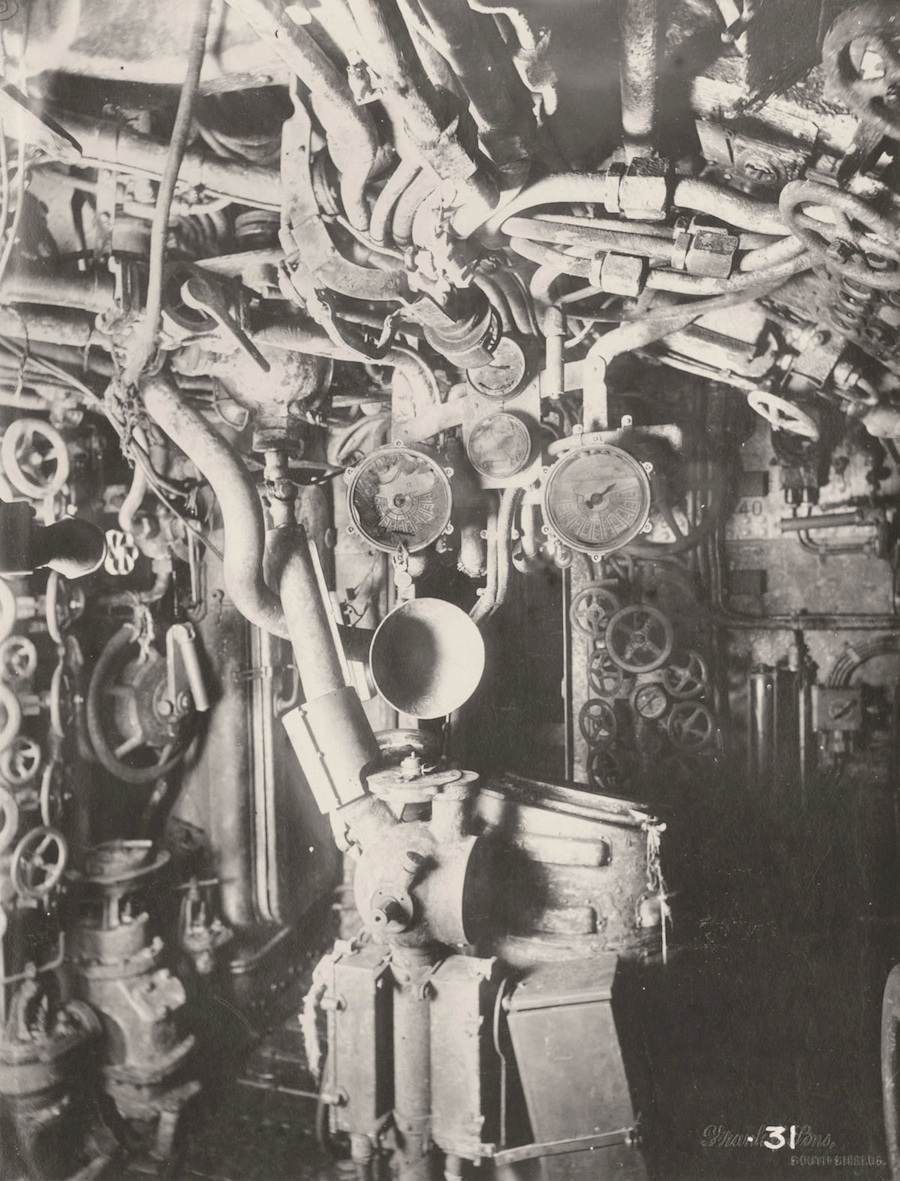

Control Room with wheel, gyro compass, gauges, telegraph and communication pipes.

View of the Control Room with access to conning tower.

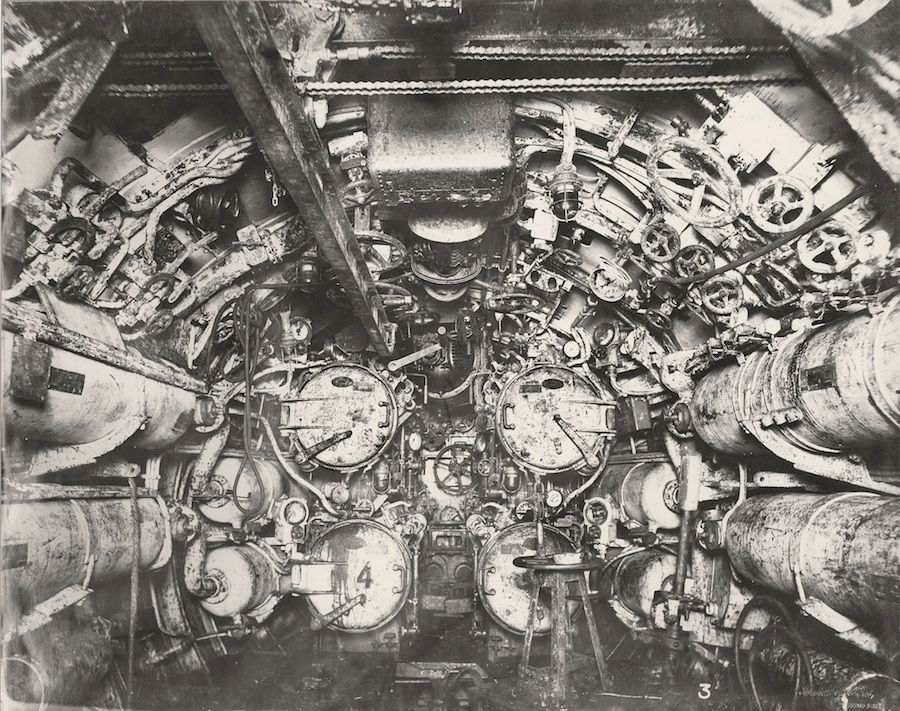

The forward Torpedo Room.

View of the U-Boat’s four Torpedo Tubes.

The forward Torpedo room.

Inside the Torpedo Room looking aft, overhead a torpedo lifting beam.

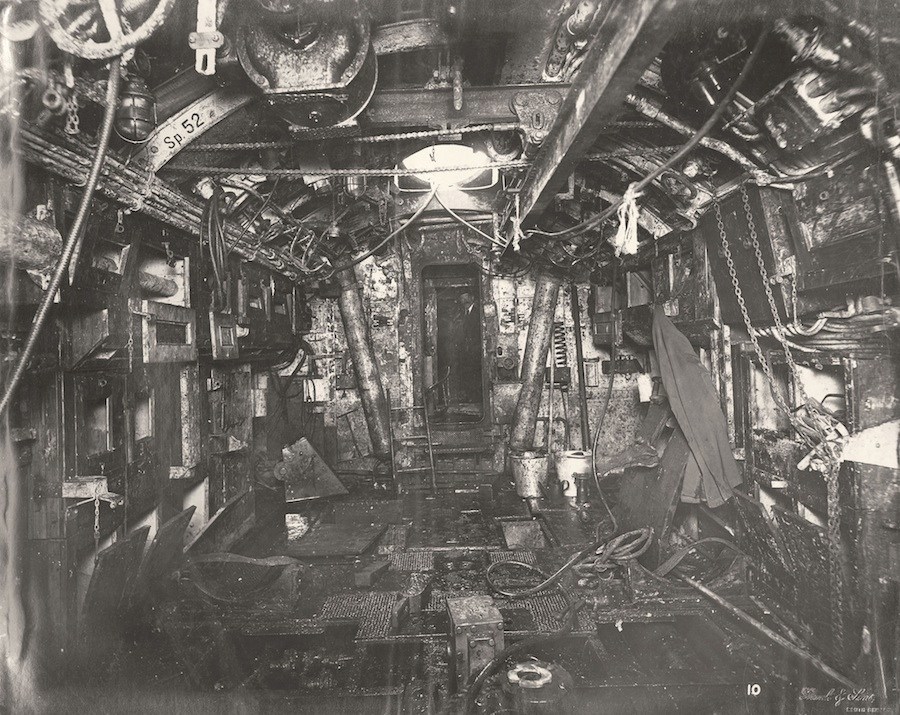

The cramped conditions of the Third Compartment including the crew lockers.

Crew room: One sailor Johannes Speiss described the humid, claustrophobic conditions as like living in “a damp cellar.”

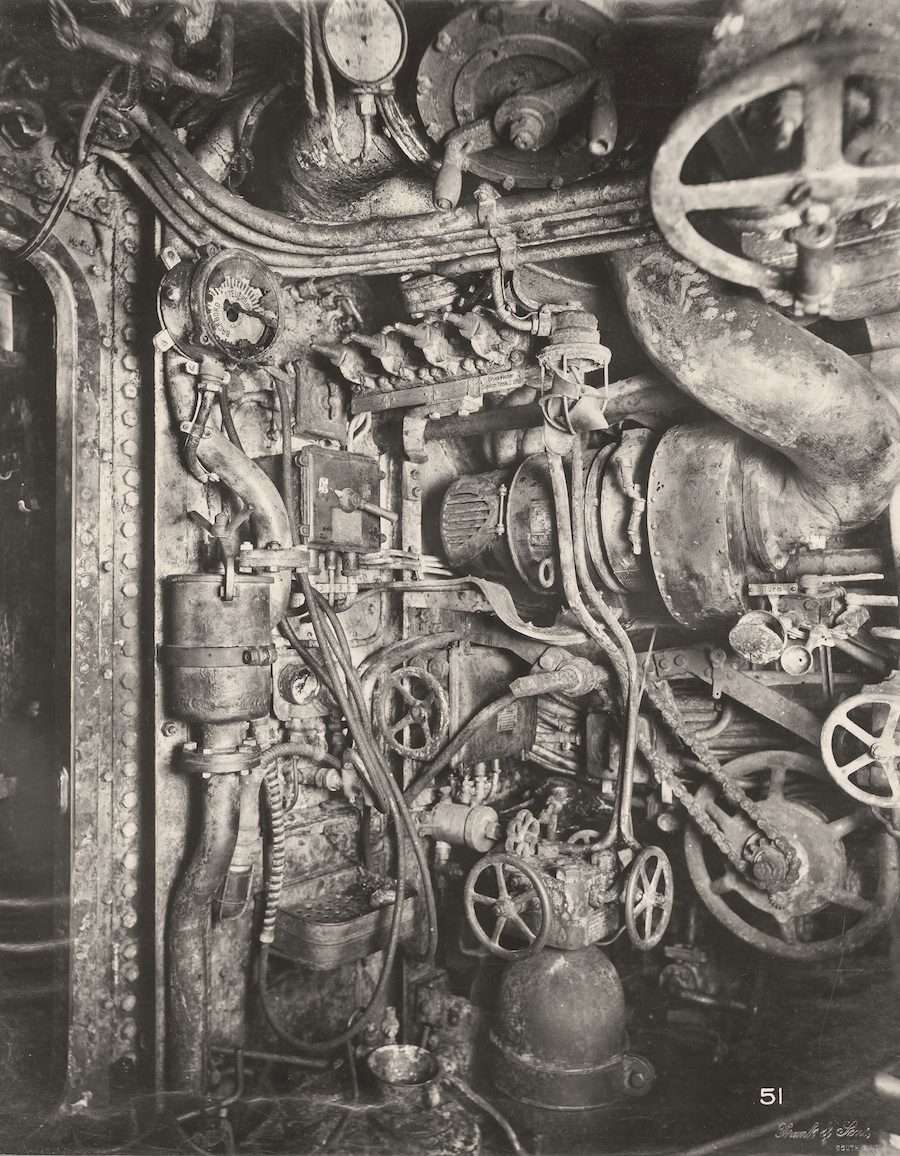

Compartment No. 5 at the starboard side.

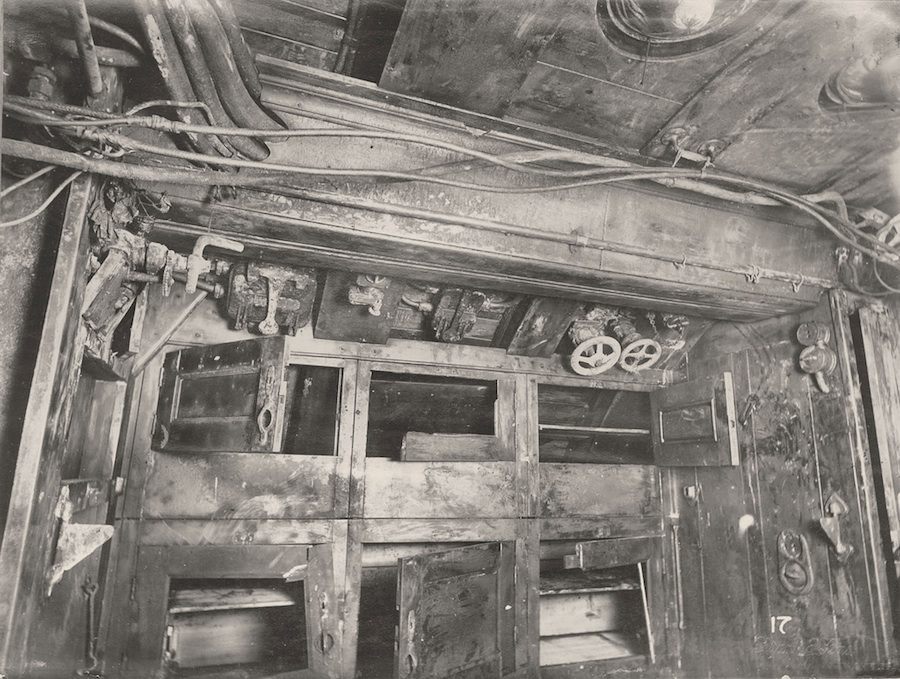

Compartment No. 6: A view of its sleeping berths and access to the Engine Room.

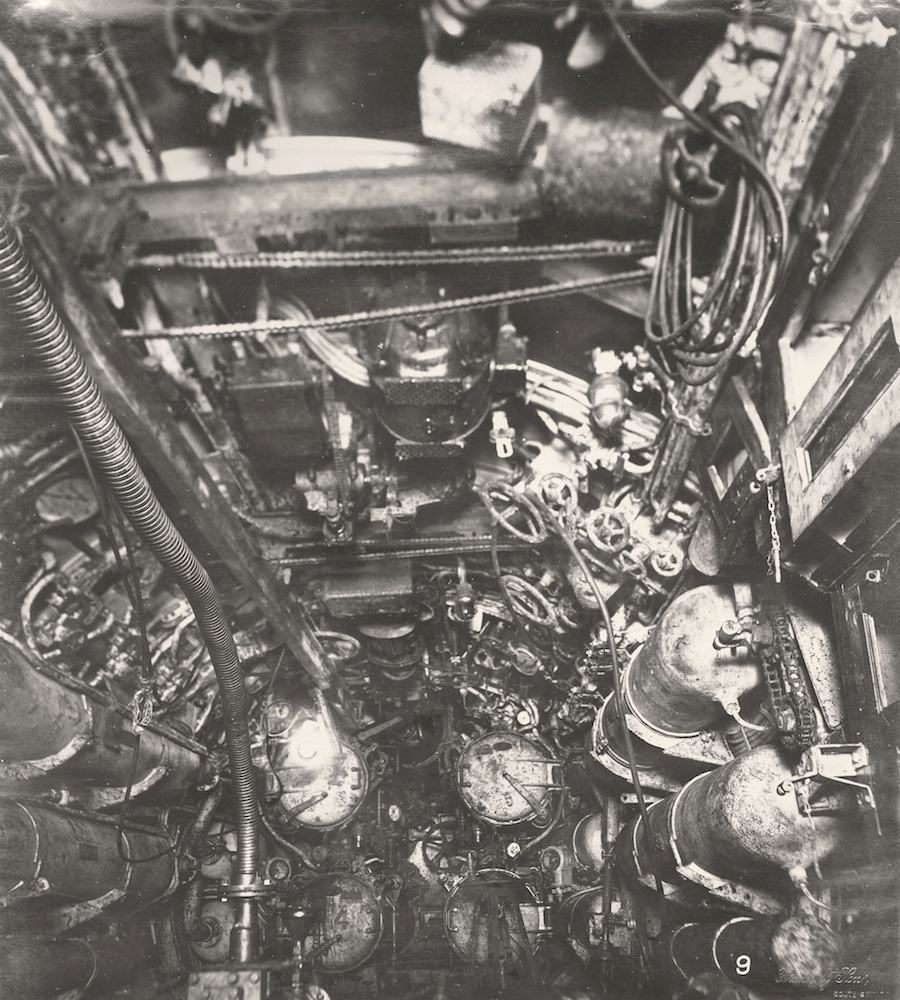

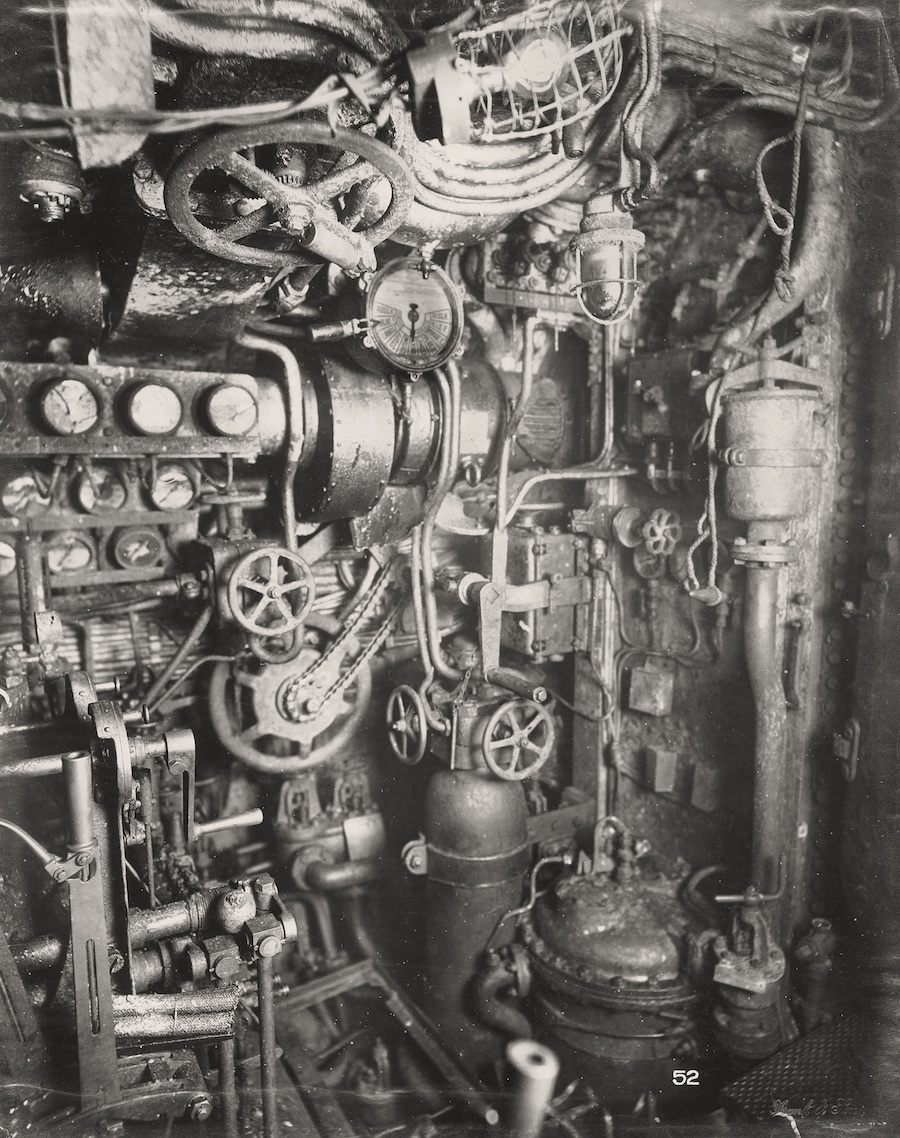

The Engine Room.

The Engine Room–starboard side.

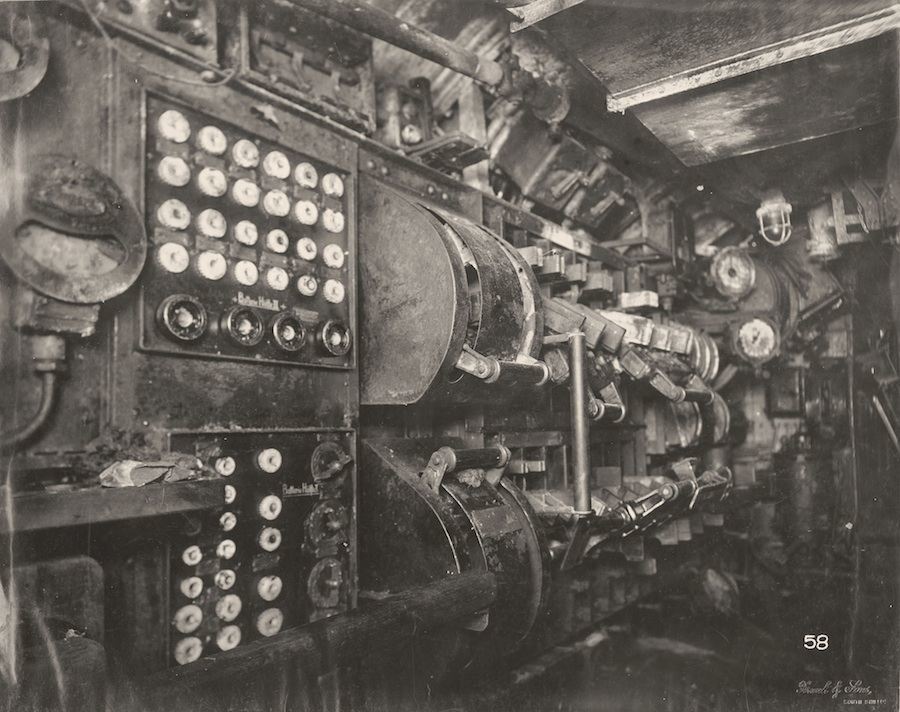

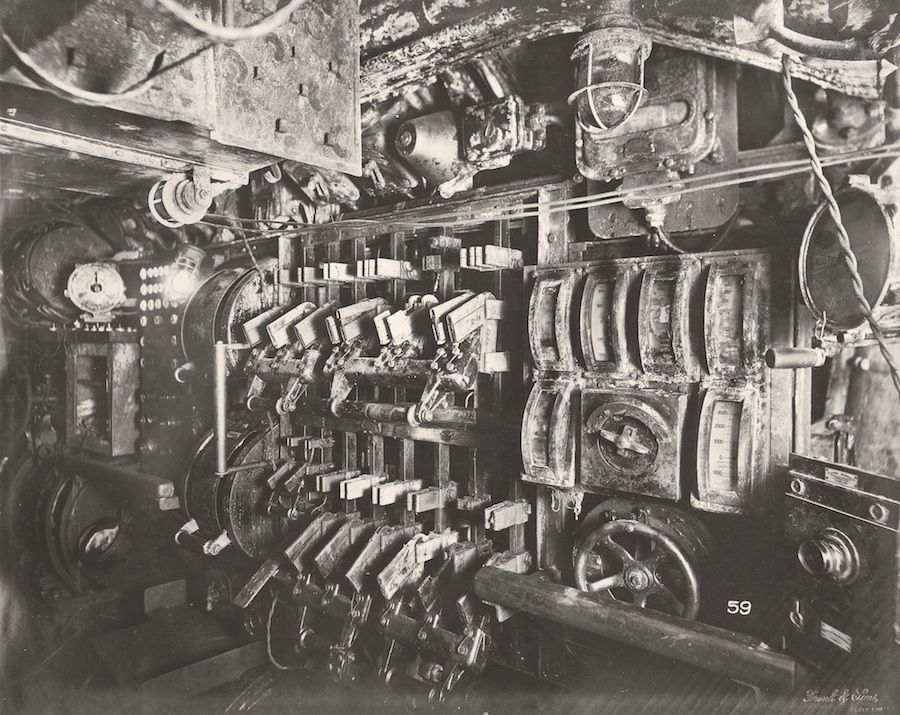

Electric Control Room with its switch gear.

Electric Control Room with view of propellor motors and main switchboards.

Electric Control Room and switch gear.

A gaggle of gauges and valves.

Via Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.